Teodora Talhoș

The October Salon, one of the most important art events in Serbia, celebrated its 60th anniversary this year. Founded in 1960 as a collective exhibition of the most significant artistic achievements in the Republic of Serbia, the Salon was also meant to commemorate the Liberation Day of Belgrade, when the city was liberated from German Nazi occupation in 1944.

Looking back at the Salon’s origins and the important event that prompted it, I started reflecting on our current situation in Europe. This year hasn’t been particularly smooth – the war in Ukraine is still raging, devastating lives and cities, and the US elections have produced a result that is certainly disappointing and worrying. The situation at home, in Romania, was the cherry on top. We have just witnessed one of the most shocking presidential election results – a virtually unknown delusional mystic with a right-wing extremist discourse, came in first in the first round. Suddenly, many people, including me and my circle, became afraid for our own safety and integrity. We understood in the blink of an eye that democracy was experiencing one of its darkest moments and that we could lose our freedom in no time. In an attempt to briefly distance myself from the confusion and anger that was unfolding at home, I made a short trip a couple of hours away to Belgrade. I was fascinated by the idea of an art event with such a long history, first occurring under the influence of the communist regime, changing its form over the years to reflect (or refute) au courant ideologies. But even more than that, I was curious to see the dialogue between artworks dealing with burning issues and how they were placed in various historical locations, in a city that is also experiencing a currently unfolding crisis.

The Salon, with the striking title What’s left? (Šta ostaje? in the original Serbian), which today has the format of a biennial and is funded by the city of Belgrade, had three different concepts, with several exhibitions taking place in different relevant cultural venues in the city. However, the diversity of ideas was united by a common thread that wasn’t so easy to pin down. For me, this red thread could be described by a word mentioned by one of the curators, Dobrila Denegri, in an interview for the exhibition catalogue. She talks about a term coined by Brian Eno, “scenius”, which refers not to the genius of an individual but to the talent of a whole community. That’s the general feeling the Salon gave me: that of a whole community, local and global, national and international, facing the same difficulties, be they social, political or economic, and responding to them in a similar way – with solidarity, defiance, and empathy. And that is what gave me hope in those dark days.

The first part of the Salon, Trace, curated by the Italian Lorenzo Balbi and the Belgrade-born Dobrila Denegri, was known to me before I saw it in person because of its ambitious goal – to use the biennial’s budget to buy a permanent art space that could host future Salons, artists, and their projects. Despite its 60 years of existence, the Salon still does not have its own space. Unfortunately, the idea could not be realised due to bureaucratic hurdles, but it did raise awareness of the lack of spaces for culture in Belgrade. While the problem of space and funding for the arts is a never-ending one, it has become increasingly urgent in recent months. Inappropriate and inadequate funding for the arts is indeed a status quo in Eastern Europe and the Balkans in general. But the fact that Berlin, for example, one of the leading European cities for contemporary art, a place not only of innovation and experimentation, but also a refuge for so many artists from all over the world, is currently facing a cut of €130 million, is alarming proof that opportunities are shrinking everywhere.

Trace proposed a series of artistic interventions, many with an activist approach, that directly addressed the lack of state support for the arts and advocated for the reclaiming of public space. In an interview for the catalogue, Ms. Denegri recalls the socialist era, when every newly built skyscraper in Belgrade had to have an artist’s studio on the roof. From today’s turbo-capitalist perspective, it’s hard to imagine what free working and living spaces must feel like, as the city centre is rapidly gentrified and cleansed of unwanted social categories through grandiose and highly problematic projects such as the government-supported Belgrade Waterfront project.

The frustration at the difficulty of getting officials to pay attention to these issues, as well as the hardship of feeling invisible and unheard, was addressed by Studio Orta’s intervention in public space at the opening of the Salon. As part of an ongoing project entitled 70 x 7 The Meal, a performance was organised in front of the Belgrade Cultural Centre and included a meal for 200 guests. They had the opportunity to discuss with cultural workers and artists, the role of art in society today, and national cultural policies and working conditions, while literally sitting at the same table. In this gesture of gathering, feeding, and discussing in an informal setting, the artists showed in a non-confrontational way that open dialogues are possible and that solutions can be found together. Would public policy look different if we had the ear of politicians once a month over lunch? Would they care more about the crucial role of the arts and the importance of supporting them? Knowing our mostly corrupt politicians, probably not. But at least we would get them to listen. And one can only dream.

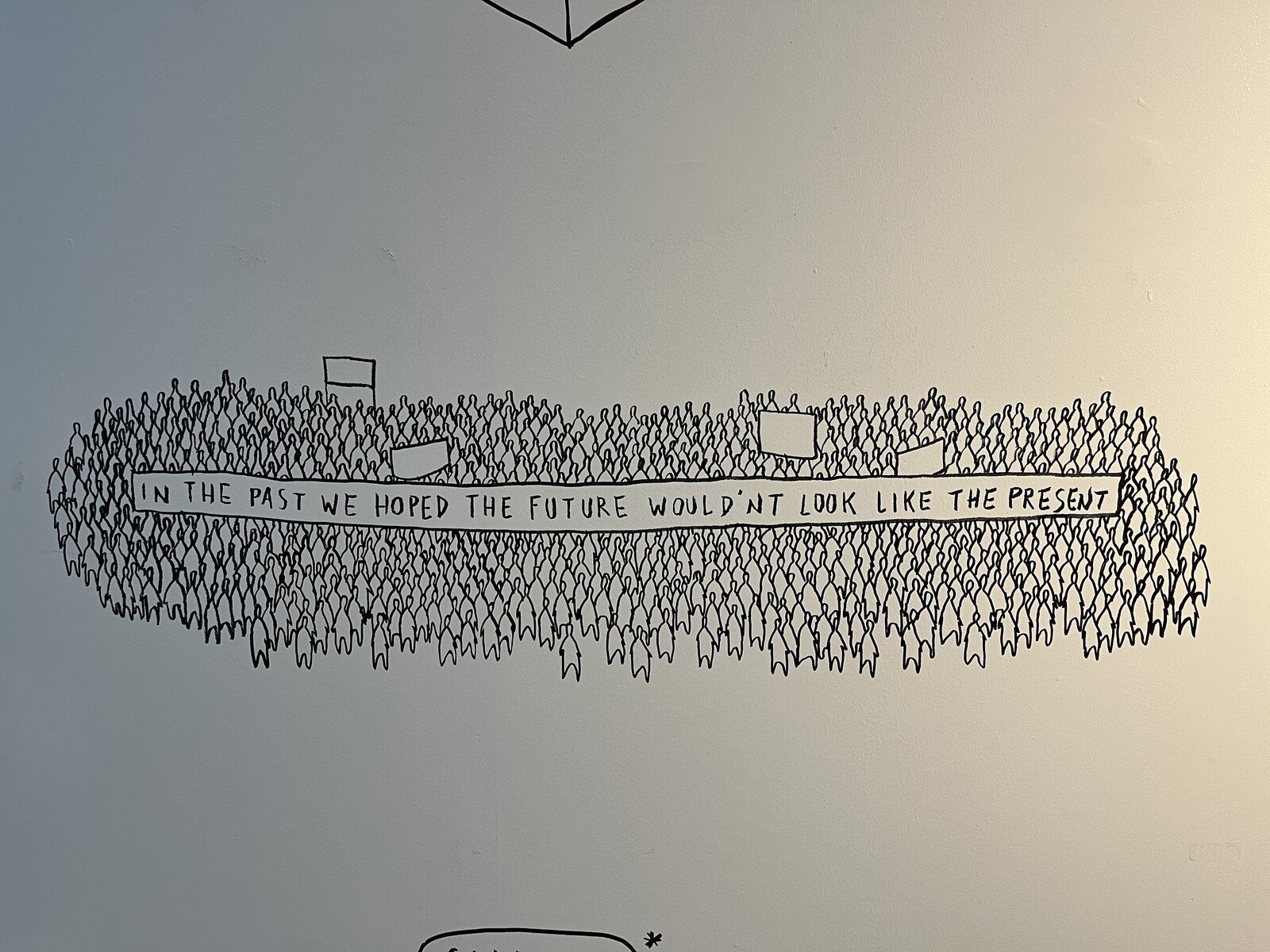

Although Trace implies something that remains, preferably in visual form, most of the projects and artworks presented had an ephemeral character. Nevertheless, they opened up discussions about the future. One such example that stayed with me for a while was Aldo Gianotti’s interventions on the walls of the Belgrade Cultural Centre. One of them depicted a faceless crowd with a long banner stretching across it that read: “In the past we hoped that the future wouldn’t look like the present.” Have we been reading about the looming rise of right-wing extremism in Europe since 2015? We have. Were we aware of its implications, all of which had been expressed by many experts? We were. Did we expect it to actually happen? We didn’t. Another read “everything will be,” positioned just on a corner, without continuation. We have probably grown tired of believing that everything will be all right.

The second part of the Salon, The Aesthetic(s) of Encounter(s), curated by Matthieu Lelièvre, Head of the Collection at the Lyon Museum of Contemporary Art, and Maja Kolarić, curator and director of the Belgrade Museum of Contemporary Art, explored the concept of encounters within an international art exhibition. While this part of the exhibition did not become a place of unexpected or surprising encounters, as none of the artistic positions presented were strangers to the art world or the spotlight, it did superimpose artworks that together, created strange and compelling dialogues. One would not necessarily expect to find, in the dark bowels of the Belgrade City Museum, a touching and baroque video by Anne Imhof leading to a spectral large-scale painting by Biljana Đurđević. Anne Imhof’s Youth (2022) follows a group of horses running free in what appears to be an abandoned, remote, snow-covered Brutalist housing estate. The dramatic soundtrack, Bach’s “St. Matthew Passion”, lends the scenes a sense of almost melancholy, as one understands that even if the human race is extinct, animals will continue to thrive and live freely, unfettered by human constraints. It is also a reminder of the importance of community in the face of adversity. Imhof was partly inspired by the wild horses that live in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, a highly radioactive area where human life is restricted and wildlife thrives. The film, originally made for the Garage Museum in Moscow, is set in a peripheral district of the capital, Severnoye Chertanovo, which was built after the Stalinist era as an experimental mass housing project. However, there are no people in the film, which creates a strange contrast between the massive, grey-walled buildings and the free-roaming horses.

The music, along with a sense of alienation and confusion, led the viewer into the next room, an eerie space reminiscent of an abandoned underground bunker. In its centre, flanked by large concrete columns, the monumental oil painting Present State (2024) by Biljana Đurđević, made the viewer feel as if they had entered another realm, devoid of human presence. The almost 10-metre-long painting depicted a dilapidated room full of white, old-fashioned hospital beds, each with a hole in the mattress, as if the people had been lying there for a very long time and just got up and left. The only source of light is a couple of trap doors in the ceiling, which lets in showers of spectral white light. The artist has been concerned for many years with aggressive capitalist mechanisms that make her subjects feel as if there’s no way out, creating a general sense of apathy and lethargy. The sense of absence in the painting refers to the people who have lost their lives as a result of inhumane treatment. But the striking artwork, placed in the desolate basement with no windows and no apparent doors, managed to make the viewer feel as if they were inside the claustrophobic scene; a place from which to contemplate the inability to escape today’s horrors, which include not only the intricacies of capitalism, but also war in the proximity and the destruction caused by climate change.

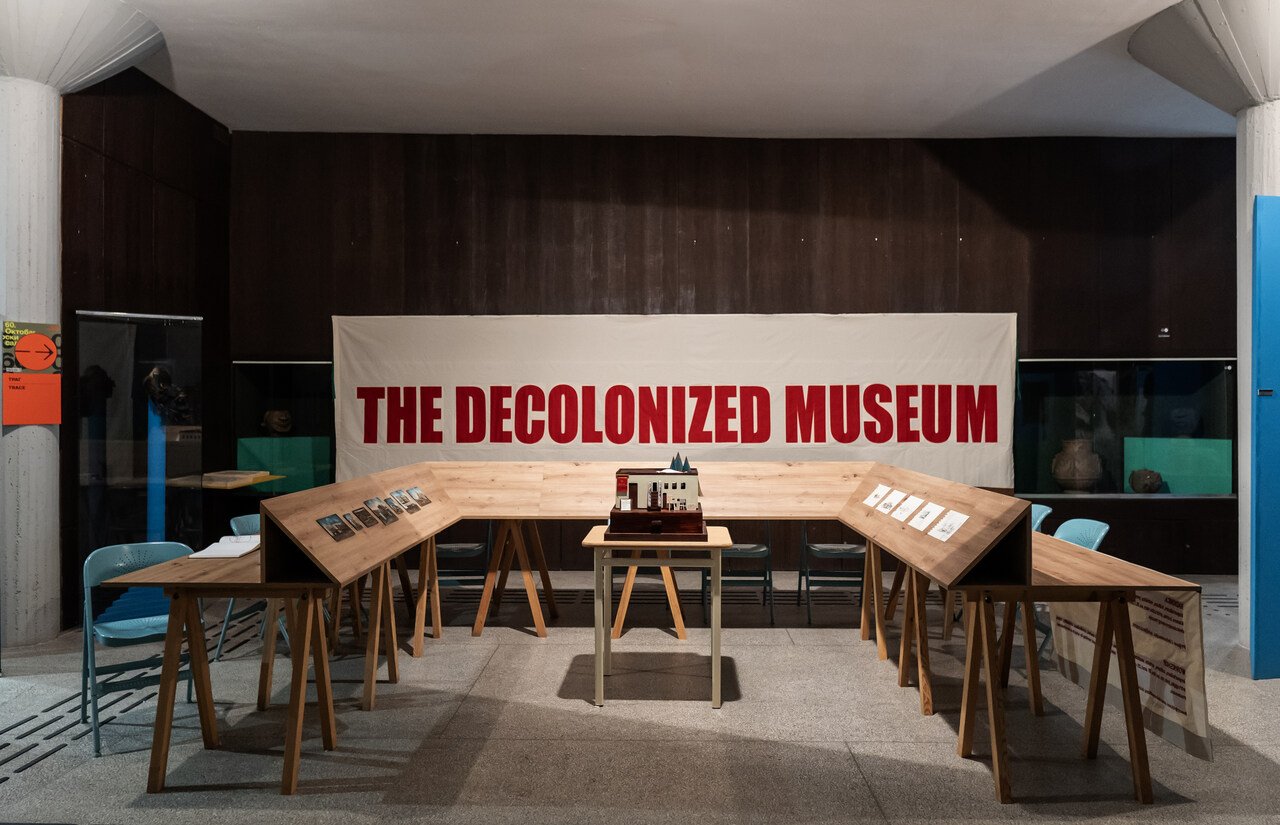

While the atmosphere was a little sombre there, the third and final part of the Salon brought a lighter and exciting incentive: Hope is a Discipline, curated by Emilia Epštajn and Ana Knežević, both curators at the Museum of African Art in Belgrade, and Lina Džuverović, a professor in London. The title comes from Mariame Kaba, an activist and educator whose work focuses on ending violence, abolishing the prison industrial complex, and transformative justice. It suggests that hope should not be something we feel from time to time, but that it needs to be nurtured, exercised, and actively engaged. One of the venues was the very unusual Museum of African Art, located in a posh, secluded, green area of Belgrade. Unlike the majority of such museums in Western European countries, which have their roots in colonialism, this one was opened in 1977 as an expression of the good diplomatic relations between Yugoslavia and West African countries. Its collection is made up of objects donated by benefactors with close ties to Africa, such as ambassadors, engineers, and doctors. Hope is a discipline that brings together grassroots initiatives, artists, and networks whose practices explore the potential of artistic acts as coping mechanisms against state oppression, corporate exploitation, and environmental challenges. The exhibition at the Museum of African Art drew inspiration from the museum’s history, highlighting the activities of the Non-Aligned Movement and the links between Yugoslavia and other Non-Aligned countries, raising questions about workers’ rights, equality, and the role of women. One of the installations, Work Won’t Fix It (2024), a collaboration between Kiluanji Kia Henda and Tiago Mena Abrantes, consisted of 24 posters questioning the ways in which capitalism places productivity and work above the innate dignity of the human being. The posters reflect on the myth of meritocracy or hard work leading to prosperity, in a world where the already large gap between social classes is widening every day. Using the name of a fictitious anti-capitalist movement called Kunanga, a slang word used in Luanda to describe people who have lost the will to enter the labour market, the posters criticise the constant obsession with numbers and profit, without any consideration for human life. My favorite one was campaigning for a type of laziness I wish we all had – laziness for war and violence.

When I returned to Romania, the political situation took a strange and unprecedented turn – the authorities decided to recount the votes. They released documents showing that the winner of the first round had benefited from a manipulative TikTok campaign used by the Kremlin in pre-war Ukraine and Moldova, so the presidential election was cancelled and postponed until next spring. Now, with an unexpected rise in far-right extremism and shaky democracy across Europe, the only thing to do is learn from others who have been or are going through similar situations. And, as many of the artworks in the October Salon suggested, to remember that there is always a way to resist, be it through poetry, visual art, or simply coming together.

Artists: Alessandra Saviotti, Francesco Fonassi, Lucy + Jorge Orta, Alfredo Jaar, Maria Eichhorn, Daniela Ortiz, Nemanja Nikolić, Nina Ivanović, Marija Šević, Lidija Delić, Ministry of Space, Aldo Giannotti, Mane Radmanović, Ana Ereš, Ivan Petrović, Jesper Just, Marina Marković, Randolpho Lamonier, Malgorzata Mirga-Tas, Annika Kahrs, Jeppe Hein, Anne Imhof, Biljana Đurđević, Ivan Šuletić, Damir Radović, Edi Dubien, Kyungah Ham, Nikola Dimitrović, Malek Gnaoui, Feminist Duration Reading Group (FDRG), Jelena Savić, Mwana, Caravan, Milica Ružičić, Adrian Melis Sosa, Kiluanji Kia Henda, Darinka Pop-Mitić, Kathrin Böhm, Jelena Micić, doplgenger, And Others: The Gendered Politics And Practices of Art Collectives, Milica Dukić

Exhibition Title: What’s Left? 60th October Salon

Curated by: Lorenzo Balbi, Dobrila Denegri, Lina Džuverović, Ana Knežević, Emilia Epštajn, Matthieu Lelièvre, Maja Kolarić

Venues: Cultural Centre of Belgrade, Pavillion in Cvetni Trg, Salon of Museum of the City of Belgrade, the Gallery of the Faculty of Fine Arts, the former Akademija Club, the Gallery of the Association of Fine Artists of Serbia, the Gallery of the Union of Fine Artists of Yugoslavia, Museum of African Art, windows of the French Institute and public spaces in the city.

Place (Country/Location): Belgrade, Serbia

Dates: 20.10-1.12.2024

Photos: All images courtesy of October Salon.