The 9th Triennial of Art and Environment dares you to enter: A conversation between Jure Kirbiš and Hana Čeferin

“If we think of Earth as our home, then this is a house that is haunted,” writes curator Jure Kirbiš in the introductory text of EKO 9: Eyes in the Stone, the ninth triennial of art and environment in Maribor, Slovenia. The triennial has historically explored the connection between art and the environment, for this edition, it draws a timely parallel between ecology and horror. Set in an abandoned modernist sanatorium in the city, the exhibition combines works by 36 artists in an attempt to analyse the discomfort and fear we feel when thinking about the future of our planet.

“Atmosphere, escalating tension, menacing moods are some of the essential building blocks of the horror genre. Natural phenomena, forces of nature are often the means of creating an atmosphere. Weather, terrain, sounds and apparitions, flora and fauna all participate in the narrative, stirring imagination to recognise and confirm our fears in the face of the cruel indifference of existence,” writes Kirbiš, who clearly hasn’t set out to moralise. Instead, the aim of EKO is to tell a story; a dark tale with twists and surprises waiting behind dark corners, but one that feels more suited to our current state of environmental anxiety than any other genre.

Hana Čeferin: EKO opened with its ninth edition in May, as a triennial with a long tradition. Before discussing the current edition, I wanted to start this discussion by going back to its first edition, which reaches back to the 1980s.

Jure Kirbiš: The EKO Triennial now takes place at a time when environmental changes and the questions they raise have become increasingly urgent. In fact, we’re confronting them whether we choose to or not. Art reflects this urgency, and many biennials, triennials, and exhibitions (such as KLIMA in Vienna) are emerging to address these topics. What sets our triennial apart is its foundation in a tradition that dates back over forty years, to 1980.

Back then, my predecessors at the gallery – most notably Meta Prosenc, then director of UGM (Maribor Art Gallery) – established the triennial in a pioneering way. It began in Maribor, a key industrial hub in what was then Yugoslavia; home to the car industry, the Yugoslavian army’s manufacturing sector, and a robust textile industry. By 1980, the environmental impact of these industries had become apparent, particularly in the pollution of the Drava River. Factories like the MTT textile plant dumped chemical waste directly into the river and air pollution led to acid rain, leaving visible damage on Maribor’s public monuments, which is still evident today.

EKO was founded in response to these changes, reflecting on the growing environmental challenges. Ecological theory was already well-developed by then, so a triennial focused on art and ecology was not out of place.

HČ: How come the triennial was put on hold for a time?

JK: The event ran until 2006, when it was paused for 15 years due to shifts in UGM’s program vision, which led them to question the relevance of the format of EKO at the time.

In 2021, or even a few years earlier, we began contemplating the revival of EKO, aiming to bring it back in an updated and enhanced form. One significant change was renaming it from the “Triennial of Ecology and Art” to the “Triennial of Art and the Environment.” This allowed us to expand the scope of how we understand the environment. We also decided to host each new edition in different locations within Maribor – spaces that resonate with us and invite engagement. It’s worth noting that EKO had already played a vital role in art in public space, but we wanted to take this further. We now focus on non-institutional spaces, often with distinct architectural or industrial heritage, and which are significant within the city’s collective memory. These are usually inaccessible or closed-off places, but we open them to the public, unlocking new interactions with the city.

HČ: EKO has, even in ex-Yugoslavia, merged art and ecology in a really unique way. There have been showings of both contemporary works as well as canonical ones. How has that developed through the years?

JK: Well, what I can say is that for the past two editions, we have showcased both pioneers of ecological thought and contemporary works, featuring a mix of international and Slovene artists. Our aim is to highlight that ecological awareness existed even before EKO’s founding. In EKO 8, we featured works by Yoko Ono and Stane Jagodič, both of whom have engaged with environmental issues since the 1970s. Mako Sajko presented his film Poisons (1964). In this edition, we’ve included Oton Polak, who contributed a series of drawings titled Beetles (1980) for the first EKO triennial. We’ve also showcased David Nez, a founding member of OHO, demonstrating that much was happening in this field well before today.

HČ: Was EKO always a curated exhibition?

JK: The first triennials, from 1980 to 1991, primarily featured works from across Yugoslavia. At that time it served as a showcase of works from the various Yugoslav republics, with selections made by committees from each respective country. However, the format evolved after that, shifting its focus to a more international scope. EKO exhibitions with titles like American Dreams and Continental Breakfast exemplified this broader, global perspective.

HČ: The real break, it seems to me, happened with the curatorial concept for EKO 8’s A Letter to the Future, where a new vision was introduced.

JK: Right, our new vision was primarily about discovering new spaces in the city and stepping slightly out of our comfort zone. While inviting an international curator is a standard practice for biennials and triennials, we felt it was essential to bring in an outside perspective to balance our local position. For EKO 8, we chose the MTT textile factory – a space that called out to be used, not only because of its location but because of its significance to the community. We wanted to merge this local context with an international perspective.

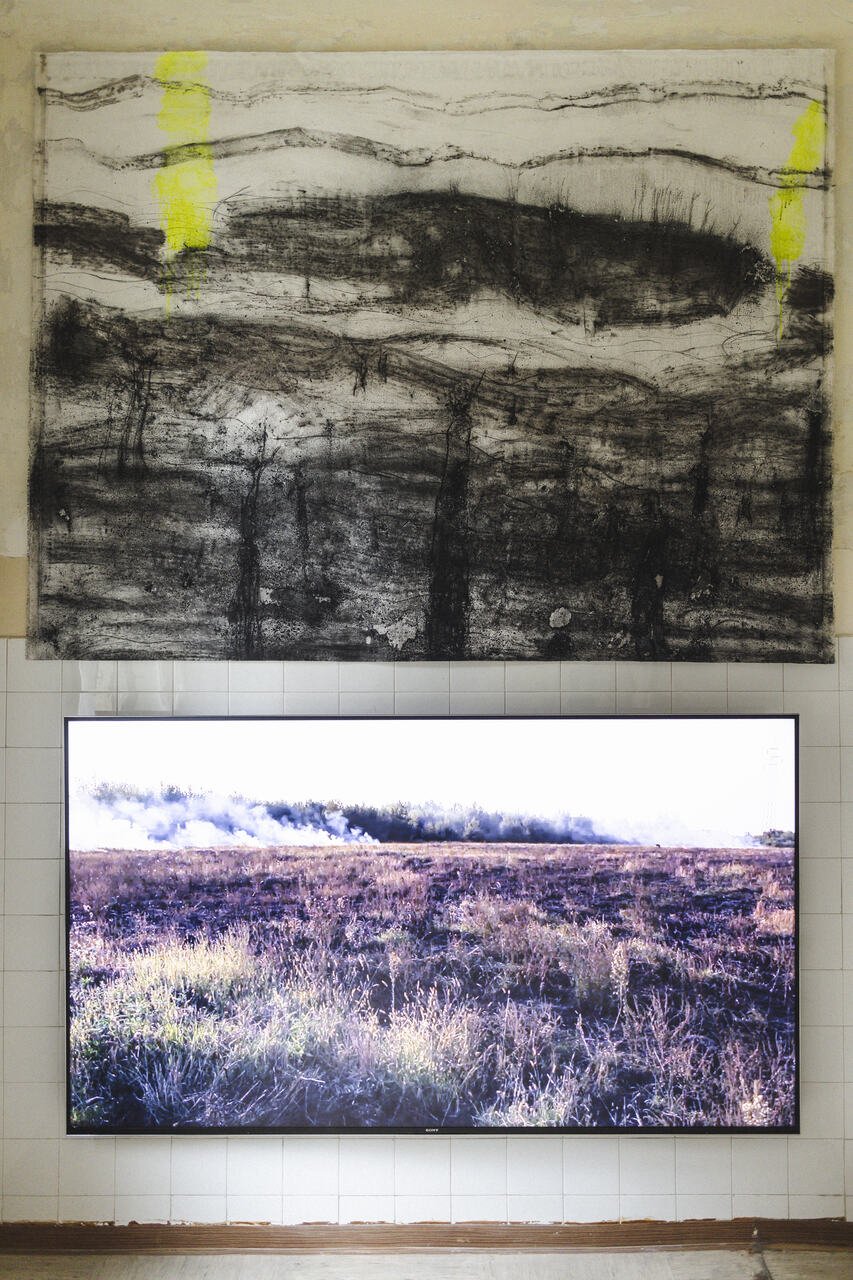

Alessandro Vincentelli, who has a keen sensitivity to these themes, joined us, and together we curated a deeply emotional exhibition titled A Letter to the Future. The show explored the intersection of environment and art through his concepts of hauntology and deep listening, which were beautifully integrated into the space. Many works were site-specific, such as Manca Bajec’s exploration of the various communities that had existed in the factory over the years, and Marko Tadić worked with the abandoned furniture left behind in the space.

HČ: This year, however, you’ve opted for a local curator – yourself – someone who bridges both local and international curatorial experience. I’ve been thinking about the implications of smaller nations inviting international curators to assess their artistic output. It can be equally intriguing to shift the focus inward and examine what emerges from within, rather than always looking outward.

JK: Absolutely, that approach can be quite interesting, especially the kind of exchange U3 does, where a local and international curator alternate in curating the triennial. It’s also worth noting that much depends on where the curator is from. Curators from the West, for example, might find it challenging to adapt to our working conditions, both financially and otherwise. For some, it’s an exciting challenge, but for others, it can be an uncomfortable experience. When we collaborate with an international curator, we expose them to Slovene art and tap into their network, but more importantly, we gain a fresh perspective on certain topics. Ultimately, I believe the key difference lies more in the working conditions than in the subject matter itself.

HČ: As the sole curator this year, I’m curious about how you approached and structured the selection of artists?

JK: For this year’s edition, I structured the artist selection based on a regional principle, similar to how ecological food is produced – following a “farm to table” approach. I invited two advisors from abroad, Markus Waitschacher from Austria and Dominika Trapp from Hungary, who both work in the same region; one that has been shaped by a turbulent history and diverse political systems. While our languages, pasts, and presents differ, the climate is strikingly similar. Nature and climate don’t care about borders, and that’s a central theme for EKO 9. We’re focusing on art that emerges from its environment and connects to cycles of food production and harvests. The question we’re exploring is: what can grow when we confront different regions?

HČ: I think this cyclical moment is very visible in the show. You opened EKO with a strong world-building narrative that is made up of several layers – environmental concerns and cyclicality, climate anxiety, and a strong element of storytelling with fairytale-like qualities. It ties everything together, from the venue to the selection of works, all aligned with the overarching theme.

JK: I suppose when you organise a triennial called EKO, you should first ask yourself what role you think art plays in relation to environmental questions. The question is, of course, are we trying to solve this looming disaster with art – or is art playing another role here? For me, art is playing a crucial role in helping to tell a story. A person creates something to communicate with other people through abstraction or metaphor, to explain the world and to create utopias or dystopias, and to confront our situation, whether through catharsis or acceptance. We’re not looking for straightforward narratives or illustrations of problems, but humans have an inherent need to reflect on things they are surrounded with. Storytelling has been man’s companion from the start, and amongst them, we often tell scary stories. These were told as warnings – cautionary tales about not approaching dangerous waters, touching fire, or entering unknown forests. I was thinking that our present moment calls for stories that might warn us, too. Not only for children, but adults especially. We like to tell optimistic stories to make ourselves feel everything will be ok, but perhaps we also need frightful stories to shake us from our stupor, to address this horror with horror. This is the starting point of EKO 9.

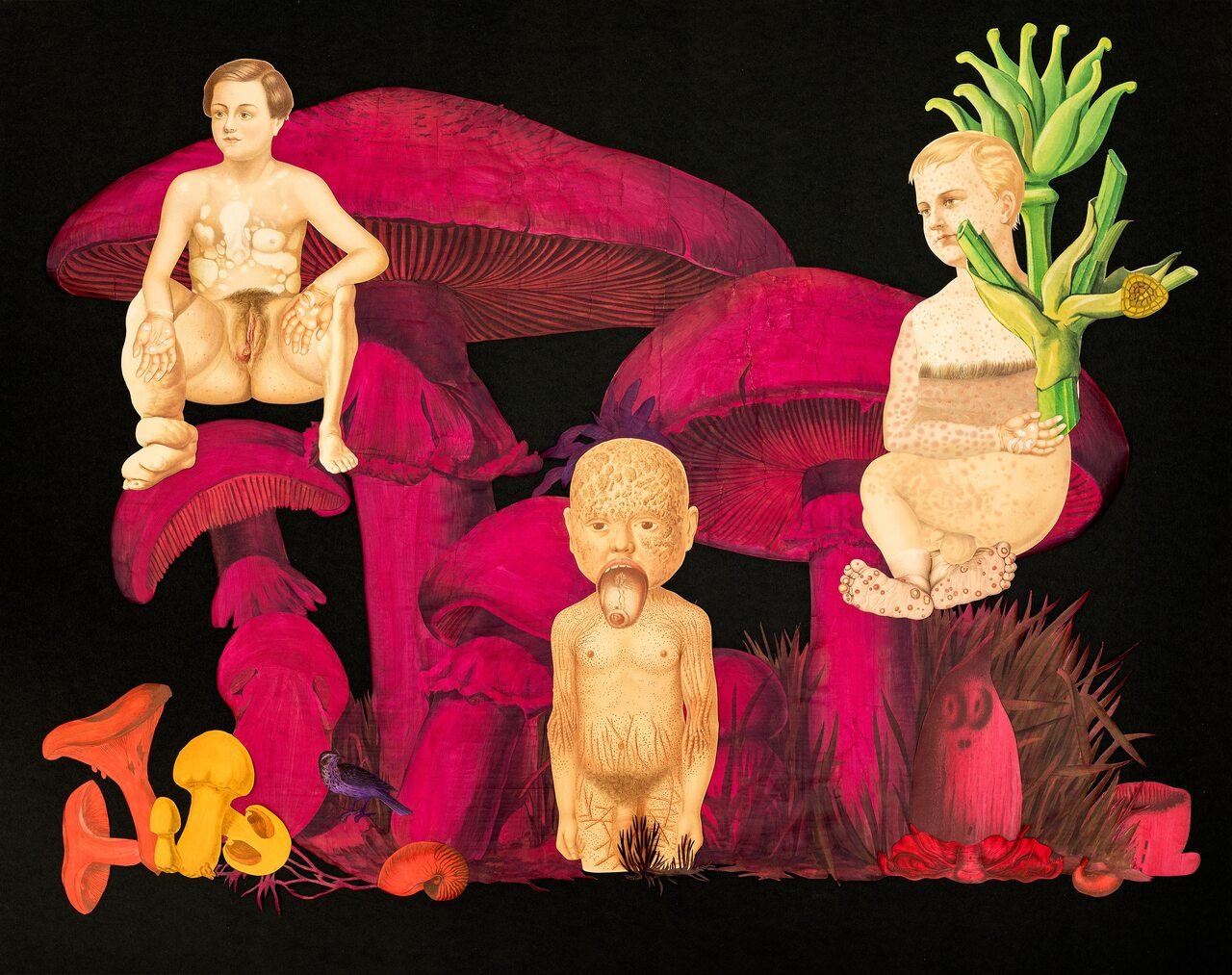

HČ: It’s also interesting to see that you’ve approached these very serious (and horrifying) topics through the genre of horror, which is often quite campy and overdone. Some works in the exhibition, like Nina Koželj’s field of giant electrified mock corn, really reflect this double nature of the terrifying and the humorous. How would you comment on this merging of the horrific and the campy?

JK: That’s a very interesting comment. In the exhibition, there’s a section called Natura mortua with a selection of works by ten artists. There, I try to question the relationship between the genre of horror and the genre of still life. It’s curious that still life is often seen as a beautiful, decorative art form, yet it can carry deeper meanings beneath its surface. Similarly, horror movies, while popular for their adrenaline rush, follow a certain formula and are often consumed as a form of entertainment. However, if we look at the still life or the genre of horror historically, they’ve often introduced much more nuanced perspectives. The horror film can address societal fears, including environmental issues, using exaggeration and humor to confront and reveal these anxieties, and look at them from a different perspective. It also forces us to look and refuses to let us turn away.

HČ: Right, we often talk about the environment and climate change as very looming, horrifying scenarios, but rarely portray them with the same methods applied through horror films.

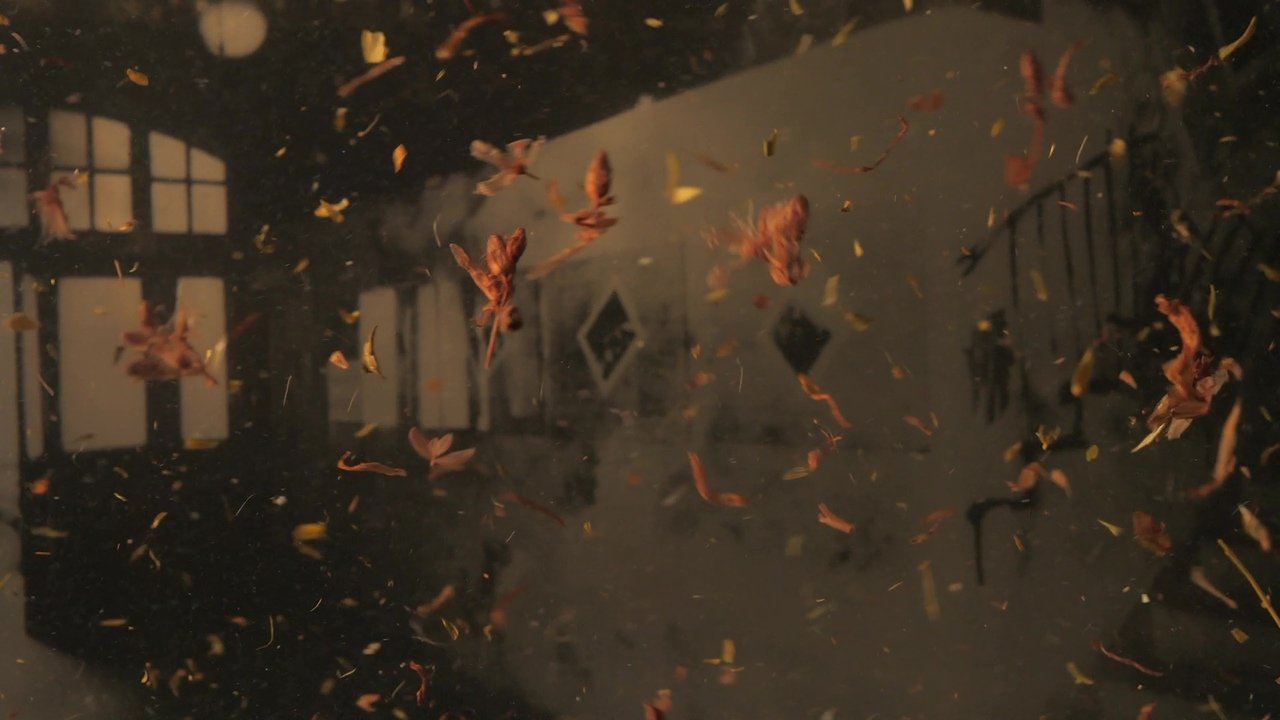

JK: Exactly. Vid Koprivšek created a new commission for the exhibition, and delved exactly into this ambivalence between climate disaster and the horror film. He articulates a key insight: while climate catastrophe is an unintended consequence of multiple factors with no single author, horror films are deliberately designed to frighten us. The effect is similar – both provoke anxiety and fear, but the horror film’s effect is fleeting, whereas climate disaster is a more enduring reality. Koprivšek has designed a rail line within his spatial composition, reminiscent of a haunted house train. This track guides us through a ghostly environment, embodying the concept of inescapability and subverting traditional horror narratives.

HČ: How does the old sanatorium space connect with the interplay of genres and horror? Its choice seems quite deliberate, but have there been any unexpected outcomes since you’ve started using this old house?

JK: The audience of EKO 9 is invited into our house of horrors – the planet is our home and this house is haunted. They step through the doors to discover multiple layers of these anxieties. I’m not suggesting that the works in the show were created with horror in mind, but they are displayed in a way that invites visitors to view them in this context.

To provide some context, the house was built in 1930 as Maribor’s first private sanatorium. Architecturally modern for its time, it featured top-tier amenities like telephones, electricity, running water, and central heating. Over the years, it transitioned from a pediatric hospital to a tuberculosis dispensary, and then fell into disuse after it changed owners in 2009. After ten years of complete abandonment, these spaces became frightening, like out of a horror movie. When we first stepped through the different doors of the house we didn’t even know what would be behind them. There was still an examination table in one, with a recently discarded chocolate wrapper. There was an anatomical model in another. It felt uncomfortable.

But this setting offered a great parallel to the exhibition’s themes, particularly the element of health. For instance, Gašper Kunšič’s work incorporates the concept of self-healing. The building’s neglected state, with peeling plaster and visible layers of decay, creates a dialogue with the artworks. One striking feature was a wall smudge that resembled a female head, which inspired Edith Payer’s work Gallery of Portraits. Her series of objects that look like they have faces was placed around the silhouette in the wall, which led us to the story of Ajdovska deklica, the Slovene folk tale about a girl trapped in the mountain wall. She was our little saint who looked after us and inspired the title Eyes in the Stone. She’s the personification of nature that invokes horror with her mute, unmoving, stoney gaze. We’re under her thumb, we exist in her world, but we’re also caught in the stone ourselves, mute observers of the world changing for the worse around us.

HČ: There’s another mountain-themed work in the show, the first Slovene feature film In the Realm of the Goldenhorn (dir. Janko Ravnik, 1931). How did it come to be in the show? The silent film feels almost uncanny in the old sanatorium…

JK: Well, as I was writing the exhibition text, I wrote kind of instinctively that we have now “entered the realm of the Goldenhorn.” This phrase is a nod to the first full-length Slovene feature film, which is also linked to the story of Ajdovska deklica. Nature sets the tone, even for the internal states of the protagonists. There are two silent films in the show – Ravnik’s from 1931 and the project Demonic Screens I-III (2017-2020) by Thomas Hörl and Peter Kozek with Alexander Martinz. Theirs is a pastiche, it mimics the silent films from that period but turns them into a horror story.

HČ: I suppose the house communicated with you in a lot of ways, but what did the community say? Since it’s EKO’s ambition to repurpose these spaces which have value for the community, I wonder what they thought about your exhibition and did they have stories of their own to tell?

JK: We hear stories from our visitors every day – whether they worked in the building when it was a hospital, were patients, or had some other connection to it. We’re collaborating with ethnographer Jerneja Ferlež, who is researching and documenting these personal stories related to the building’s history. In the past two editions, many locals visited out of curiosity about the spaces or their personal connections to them, in addition to contemporary art enthusiasts. We keep thinking about EKO as a city festival, belonging to the city, not only the institution of UGM. And we try to connect various parts of the city, including the university and smaller galleries like Tkalka, to create a more inclusive and diverse exhibition experience.

HČ: You’re clearly working to present the story with nuance – there’s an online library, a forthcoming catalogue, and different layers of the public programme. But looking ahead to EKO10 in two years, when a new narrative will emerge, do you have any ambitions or plans you can share about its future?

JK: Building on the legacy of previous exhibitions, we understand the importance of documentation. We have seven catalogues and extensive photo documentation from earlier EKO editions that are invaluable to us. We also want to create something that will live in the future, which is why we’re making a catalogue that can include texts as well as the history of the house, etc.

The triennial will, in the future, definitely demand a new environment, which after two architectural spaces demands a new typology of architecture – perhaps it will even be placed in nature itself.

Artist(s): Boris Beja, Saša Bezjak, Lan Breški, Andrej Brumen Čop, Gašper Capuder, Ana Čavić, Ines Doujak, Olja Grubić, Herman Gvardjančič, Andrea Éva Győri, Thomas Hörl & Peter Kozek & Alexander Martinz, Kier-La Janisse, Petja Kocet, Vid Koprivšek, Nina Koželj, Gašper Kunšič, Tanja Lažetić, Ana Likar, Eva-Maria Lopez, Tilyen Mucik, David Nez, Ludvik Pandur, Mila Panić, Edith Payer, Ana Pečar, Alja Piry, Oton Polak, Arjan Pregl, Janko Ravnik, Līga Spunde & Aleksandrs Breže, Dominika Trapp, Ádám Ulbert, Matjaž Wenzel

Exhibition Title: EKO 9: Eyes in the Stone

Venue: Old Sanatorium (organised by Maribor Art Gallery)

Place (Country/Location): Maribor, Slovenia

Dates: 17.05. – 25.08.2024

Curated by: Jure Kirbiš with advisors Dominika Trapp and Markus Waitschacher

Photos by: Janez Klenovšek