This conversation took place on September 4, 2024 at Kunsthalle Wien Museumsquartier, on the occasion of the opening of Domanović’s exhibition, which brings together her work (sculpture, video, print, photography and digital media) produced over the last eighteen years. Presenting over forty works, including new commissions, it surveys the development of a playful yet critical practice shaped by information culture in the post-internet era.

Carson Chan: As I scan through your exhibition at Kunsthalle Wien, I can’t help but to think about the role of history in your work and also our history together as artist and curator. Spending the last days here in Vienna, understanding the imperial history of the MuseumsQuartier, I’m almost conditioned to see history as kind of a central theme in your work. As a survey of more than a decade of work, your exhibition, in a way, is kind of a presentation of your own theory of history. Don’t worry, I’m not going to ask you to articulate what your theory of history is, because I think the exhibition is that articulation. It’s often tiring to talk about biographical details in these kinds of talks, but because you use your biography so much in your own work, I think it’s not something we should skip. So, if we start at the beginning: where are you from? When did you leave home? And of particular interest for us today, what is your relationship to Vienna? You have a long and personal history with the city, so maybe we can start there.

Aleksandra Domanović: I was born in Novi Sad in what was back then Yugoslavia, in a Slovak speaking minority. So, I speak Slovak with my parents at home. When I was three years old, we moved to Slovenia. This was in ‘84, so it was still Yugoslavia and was just changing republics, not into the country. When the war first broke out in Slovenia, we decided to stay there. Later on I went to study in Vienna. That’s my relationship to this place. After graduating in Vienna, I spent half a year in Tokyo and then moved to Berlin.

CC: Tell me more about Vienna. You weren’t studying art to begin with, right?

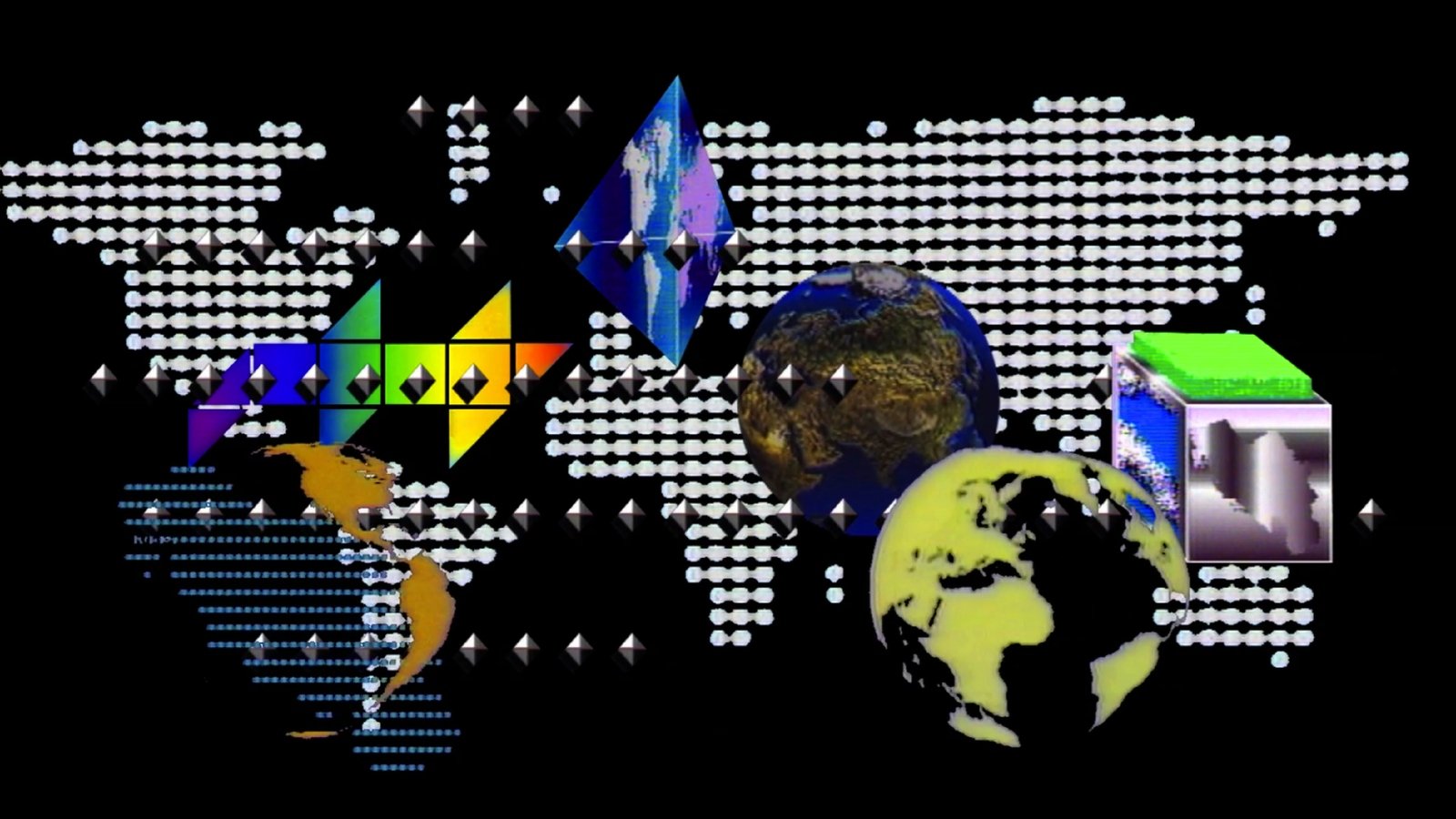

AD: I was studying graphic design because that’s what I knew as a creative practice. You know what I mean? I never had much connection with the art world, especially the contemporary art world. We had a video studio at the University of Applied Arts that nobody was really using and I loved it; I probably made more video than graphic design in my four years there. I kind of went from video to the internet, and then in my last year of university, me and three other students made a blog. This was back in 2006, when the internet and social media as we now know it didn’t exist yet. YouTube was launched at the end of 2005 I think. Facebook was just starting. There was no Tumblr, no Instagram, of course. We did this blog called vvork.com, it was spelled in a kind of wrong internet spelling. We were posting contemporary art, and that’s how I learned about contemporary art. Every day I was looking for stuff that I could post. A lot of times I say that if it wasn’t for the internet I would not have become an artist because that’s where I learned about art. But that’s also where I got my art community, because I met people from other parts of the world that were working online, and we made creative exchanges. And that was what got me into the art world. Talking to other people working online on similar things.

CC: That explains how you got into art, but I want to talk a little bit more about the role of history in the way you think about art making. Walking through the Kunsthistorisches Museum across the street yesterday I made my way to Velazquez’s infanta paintings. To think about the genre of history painting (Historienmalerei), about how paintings both record and create historical moments made me think: Is art history not the history made by art rather than the history of art? The infanta paintings were subsequently reinterpreted by Picasso in his paintings from 1957, which then kind of changed history according to Velazquez into something else. That art and history are co-constitutive and dynamic is something that I think is really interesting. We’ve talked a little bit about growing up in former Yugoslavia, that in a way the official history is something that you’ve seen change in front of your eyes. Tell me about that and how that became in many ways, central to a lot of your early work, if not still now.

AD: Maybe you’re thinking about the portrait upstairs (Portrait [mesing], 2012) or things like that. I remember when I went to school in 5th grade we had a map of Yugoslavia hanging in the classroom. And then after the summer break, when I came back to grade 6, there was a map of Slovenia there instead. So, the world shrunk. Or we had Serbo-Croatian literature and all of a sudden we only had Slovenian literature to learn. I always thought of this as a big loss.

CC: Yeah, so you saw history being written and rewritten in front of your eyes. Maybe you can talk about the video piece 19:30 (2010/11), how it started as a recording of “official” history and then how and why you remixed it.

AD: 19:30 is an anthology of television news music from the region of former Yugoslavia, where I went and collected all the TV news idents from the central TV broadcast that were broadcast at 19:30 each evening. It played this kind of rhythm-giving, conditioning role in our lives – we would always watch the news. Even though as a kid I wasn’t watching the news, the sound from the TV was always present. You would hear these tunes and you’re not even aware of them, but they are there. By chance, I heard one of those tunes on YouTube and it just brought back a flood of memories. It hit me how hypnotic it all was – like literally, at 19:30 the news would start and everyone would become kind of zombified, under its spell. But at the same time, it sounded like electronic dance music. I grew up in Slovenia at the time where in ’95 there was kind of an influx of techno and house music, and we would go to these parties. Somehow through this ident that I heard, I thought: “Oh, this was done on synthesizers in the 80s. This sounds like it just needs a beat to make it danceable.” It clicked for me – this connection between the conditioning of these live events, whether it was a techno party or a live news broadcast. Both were these shared, in-the-moment experiences. For me, growing up in Yugoslavia meant living through a time when things were open, but then the war came and everything closed off. We didn’t go anywhere for five years, and in that time, I grew up. When the borders reopened we started exploring again, traveling to Croatia or Serbia as teenagers to go to techno parties.

CC: You once told me that as a teenager, you thought that dance music was the music of the West, and hearing it and going to raves was a form of liberation from your perceived constraints. These television news jingles, this official state soundscape, getting remixed by DJs into dance music is kind of a literal performance of the process you lived through.

AD: I guess, yeah. The project (19:30) is me gathering the television news idents from the beginning of television from Yugoslavia in ’58 to the present, putting them online and making them freely available, asking people to remix them, and then putting those remixes online. For me, that just makes complete sense. At its beginnings television was such a novel medium, it was a special honor to be involved. That is how they could get really good musicians to work on these early idents, artists who were already experimenting in the late 70s and 80s with synthesizers and electronic music. So, it just needed that link somehow. There’s this repetition that happens in both the news music. I think I also loved techno for its community building role or, as they say in Berlin, techno played a role in re-establishing social relations after the wall came down. People would go party and visit each other’s part of the city. So, this is the role it played for me. And just mixing it with the news tracks or making it out of new tracks made sense because that was pre-internet times where we still got our news from television, from live-feed sources which were also communal events. It’s a combination or fusion of these two communal events.

CC: One of the first times that we worked together was at the Marrakech Biennale in 2012. The topic of creating community, of questioning what a community is and thinking about the objects important to a community is something that we discussed during that time, too. One of the first observations you made during the site visit was that even though it had been several decades since Morocco became independent from France, there are no public monuments to mark this historical moment. Before we talk about the monument you made for Marrakech, can you talk a little bit about your relationship to monuments more broadly, maybe by way of your video Turbo Sculpture?

AD: A lot of my themes come from just reading the news and stumbling upon something interesting. I found out that there was a monument to Bruce Lee that was erected in Mostar in 2005, and then there was a series of monuments like Rocky Balboa in Žitište, or a monument to Bob Marley in another village; there was an initiative to build a monument to Tupac, one to Madonna and so on. Every time I discovered a new one I bookmarked it. And all of a sudden I had a series.

CC: Why do you think people in Bosnia and Serbia were making statues to Bruce Lee and Madonna and Batman and the like?

AD: In the video Turbo Sculpture (2024), I quote a local sociologist who says the rush to put up these monuments points to an immature social conscience of the nation. He thinks they reflect a desire to connect with Europe and the United States, seen as saviors of the Balkans during its crisis. That’s one way to look at it. Some artists from the region see these “turbo” monuments as a healthy rejection of nationalism. Others argue that using heroes from movies and pop culture is just a way to avoid dealing with the violent breakup of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and the responsibility that comes with that. I think there’s a lot of truth in that last idea. The Bruce Lee statue in Mostar was an initiative from a local urban youth organization and it was a little bit different because it was paid for by the German government. The official explanation was that Mostar is an ethnically divided city and they cannot find one figure they could all honor. So, Bruce Lee, you know, no one’s going to ask him what he was doing during World War II.

CC: So as a way to avoid talking about official history, let’s bring in something completely unrelated and just have a monument of that.

AD: In some cases, yes. But in other cases, like the statues of George W. Bush in Albania and Bill Clinton in Kosovo, depict political figures connected to the region. Yet stylistically, they resemble the Rocky Balboa statue, with their impromptu construction, exaggerated postures, and overtly pro-Western aspirations. Another example is North Macedonia, where statues of Alexander the Great and Philip II of Macedon have been erected across the country. These, too, bear the hallmarks of “turbo” aesthetics: the excessive, extravagant, and seemingly random combination of local and global ornamentation. After 50 years of modernism there has been a return to figurative sculpture, but executed in a highly theatrical and brassy manner. For instance, in its attempt to construct a domestic identity, North Macedonia has created sculptures of historical personalities, like professors, depicted as grandiose equestrian monuments – even though these individuals likely never rode a horse. So “turbo” is primarily an aesthetic, which, during a specific period in mostly Serbia but also in Bosnia, reflected a mix of humor and sincerity. Monuments to figures like Bruce Lee, Rocky, or Bob Marley attempted to connect with global culture while avoiding the difficult truths of local history. However, that has changed. Today, monuments are more often dedicated to medieval figures, with the earlier pro-Western aspirations replaced by a shift towards hardcore nationalism.

CC: Back to this idea of history painting or the methods in which art has recorded official truths, I wonder how much has changed because of the internet. One of your earlier works in the show is called Hottest to Coldest (2008), which in a way, one can think of as a history painting – it’s an artwork that records history as it happens, in real time. It’s a website that shows a list of all national capitals arranged by their current air temperature. Vienna is on the second row right now, actually. Tell me a little bit about that work, how it came about. Were you thinking about the internet-enabled, hyper intensified way we have instant history? Or was it a kind of reaction to just making a website or learning about online technologies?

AD: hottesttocoldest.com came out of my obsession with the weather. The piece is from way before 19:30, Turbo Sculpture, and most of my other work. At the time, I was working almost solely with the internet and single-serving websites were a thing we were doing. The URL was usually the title of the work. Honestly I just wanted to make something dynamic, something that’s always changing – and what’s always changing? The weather. I was (and still am) obsessed with it. I’m constantly checking weather apps; it calms me and gives me a sense of control. My weather app is packed with cities because I’m always checking the weather in places where my family and loved ones are or any other locations that interest me. Before this, I had earlier projects where I embedded weather banners for different cities on my website. This was back before smartphones made it easy to do this with apps. Then I thought, kind of like with 19:30, instead of focusing on just one thing, how could I push this idea to the max? So I decided to grab weather data for all the world’s capital cities, sort them in a simple hottest-to-coldest order, and see what happens. It’s basically an always-changing text.

CC: Maybe you could describe a little bit your process and how you work. Each artwork is about many different layers of thinking – of histories, of narratives – all combined together alchemically into an object. Does it matter for you if people come to your exhibitions with some prior knowledge of the material? Or can they just engage with it at face value? How do you imagine the relationship between the complexity of your work and the encounter of the work?

AD: For example, Asija (Ismailovski) today told me “I understand every one of your projects,” because she’s from the former Yugoslavia and she knows what I’m talking about. But then I also know that not everyone’s going to know that context. To be honest, I don’t think too much about the audience. I just focus on making what interests me. If the audience can feel that, then that’s great! I do not want to be didactic. I don’t want to tell people what to think about it. My process is a research process. You talk about history and so on, but it’s also about how I love researching new things, it’s about the joy of learning.

CC: Definitely. I’ve always imagined you giving yourself a PhD with all the different projects that you do. One thing that I think we should talk about before we open it up to the audience is the role of feminism in the work. Many of the topics that you’ve been looking at – science fiction, technology, geopolitics – have been traditionally male dominated. One way to ask the question is, do you think you’re working as a feminist artist or an artist that is working on topics that just happen to provoke a feminist reading? I’m thinking about your engagement with dairy cows – which for me, combines both a technocratic world view and fertility. We have a milk industry because we exploit female cows.

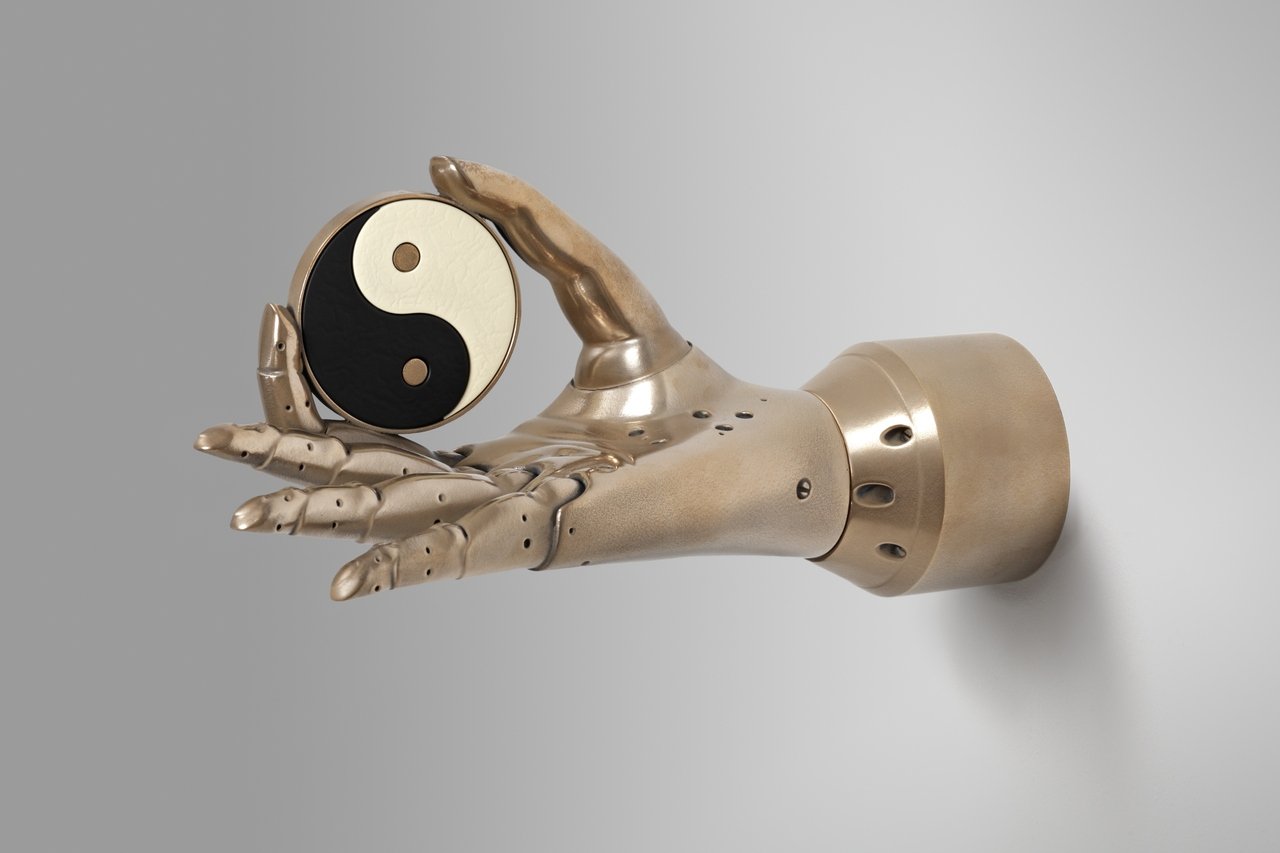

AD: Bulls Without Horns (2016) began with me following two scientists online: Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier. They were working on CRISPR, the genetic editing tool, and there was something groundbreaking in the news about them every week or two. There was always a new milestone, a new discovery being reported on. What excited me was that these were two young female scientists leading the field, and everyone was predicting they’d win the Nobel Prize for their work, which they actually did in 2020. It made me think of Rosalind Franklin and the story of how she discovered the structure of the DNA molecule. Her work was partially stolen, and she was never properly credited during her lifetime. She also passed away before she could have received the Nobel Prize. From that perspective, I found it so inspiring to see Doudna and Charpentier at the forefront of science. In my mind, they were righting a past injustice. Early in 2016 I was at the New Yorker TechFest and there was a panel on CRISPR with Jennifer Doudna on it. While some other scientist on the panel was telling us how he could certainly make actual unicorns with CRISPR, someone from the audience asked, “What about bulls without horns?” To which Jennifer replied, “That’s already being done.” The phrase “bulls without horns” stuck in my mind, but more as a symbol of castration. That was the feminist angle for me, not milk.

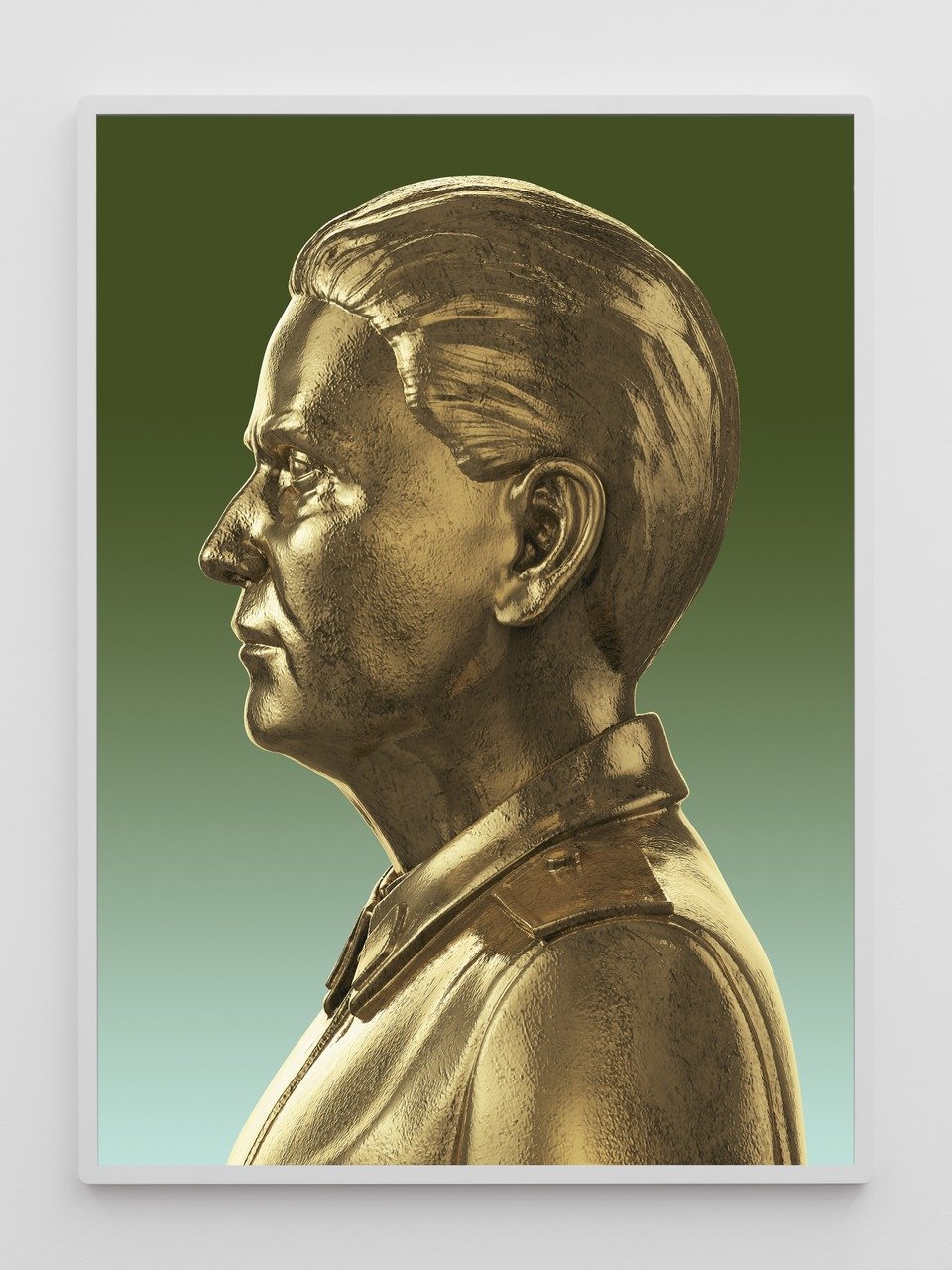

CC: There’s also your side profile portrait of Josip Broz Tito, the Prime Minister of Yugoslavia after liberation (Portrait [mesing], 2012).

AD: No, it’s actually not Tito, exactly (laughs)…it’s a hybrid portrait based on my memory of having a portrait of Tito in every classroom and my teacher, my literature teacher, that would be standing below. They’re mixed together.

CC: But it’s Tito with feminized features.

AD: Exactly. When I looked at this teacher in school, she had short hair and kind of more expressive cheekbones. To me, she looked like the female Tito. So, this was just an idea I had in my head for a long time. People have called it a queered Tito.

CC: Tell us about some new work made for this exhibition.

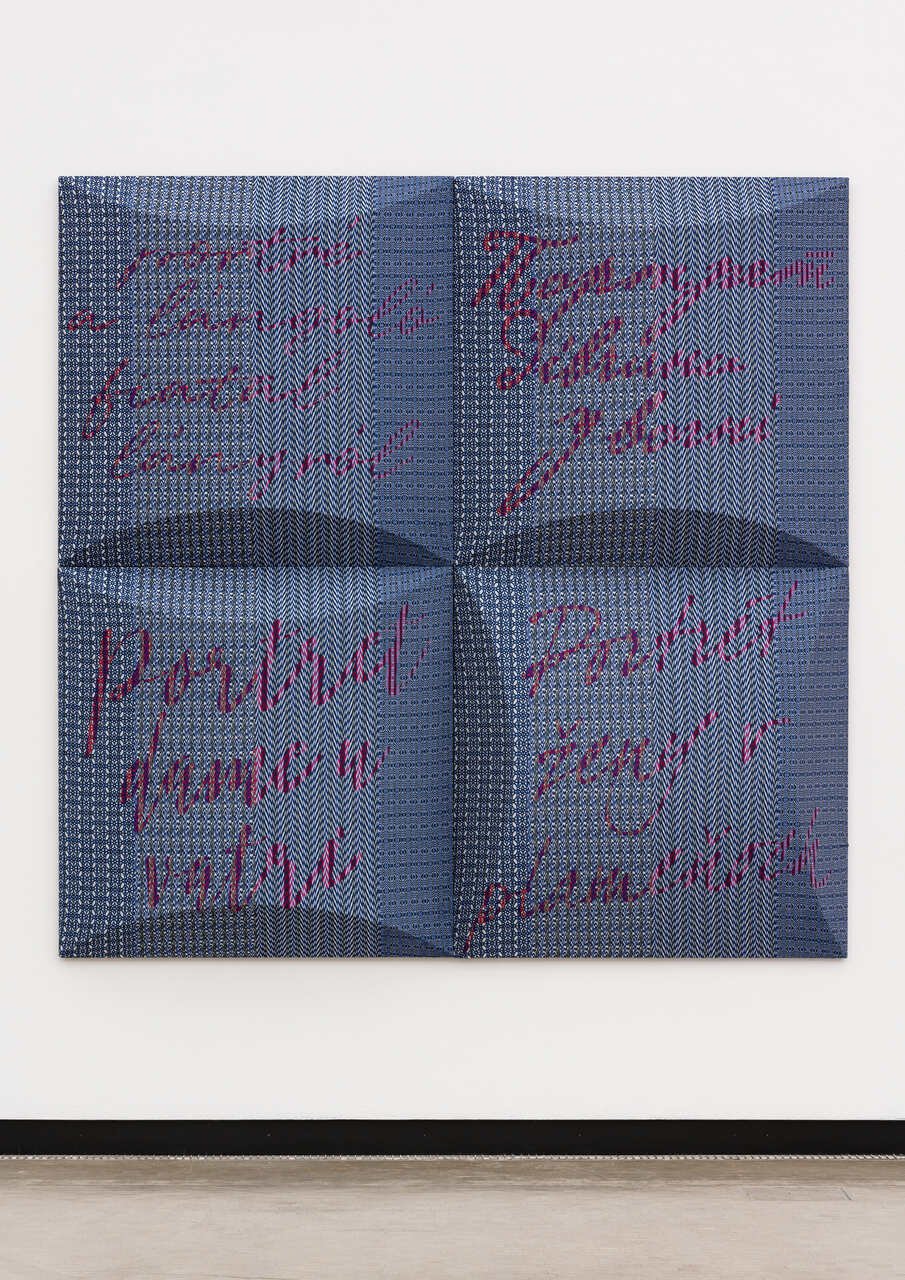

AD: For the past few years, I’ve been working with a visual phenomenon called the Bezold Effect. It’s a simultaneous color effect where small areas of color, when placed next to each other, change how we see the colors overall. I learned that Wilhelm von Bezold, the German meteorologist it’s named after, discovered it while weaving rugs. This gave me the idea to bring the effect back to weaving and explore how he might have discovered it. In these pieces, you’ll see blue lines, white lines, and what look like yellow lines. But here’s the thing – there’s no yellow yarn in the fabric. The appearance of yellow comes from layering black and blue yarn, which changes how the white threads look. For the title, I took inspiration from the handwritten poster for Portrait of a Lady on Fire, a film about the female gaze and its power. I’d explored this theme before in a silkscreen series. This time, I translated the title into the four official languages of Novi Sad, where I’m from – Serbian, Hungarian, Slovak, and Ruthenian – and wove them into sound panels.

CC: I think what’s interesting about the alternating of colors is that it comes from your research on the difference between seeing and perceiving colors. The difference between understanding what those colors are versus optically what you actually see is super fascinating. In my reading, this also extends to the questions of history, how seeing something and perceiving something historically can lead to different conclusions. Living in the US at the moment, I’m thinking about another Trump presidency and the idea of living, again, in a post-truth world. The difference between seeing and perceiving becomes even more poignant, more pertinent. One of my favorite theories of history comes from Swiss architecture theorist Sigfried Giedeon. He likened what he called contemporary history to an Alexander Calder mobile. The mobile is made of various parts that are moving in relation to all the other parts. Seeing the mobile from any point at any given moment would produce a different image. It’s the same object but depending on the moment, it appears to be different. History, Giedeon claims, is dynamic and open to interpretation. I thought that’s interesting and perhaps kind of fitting here as there are several things in the exhibition that keep changing in real time. I also imagine that installing this show must have confronted you with your own history. What were some of your first thoughts after the exhibition was installed?

AD: These thoughts already came up when I was working on a SketchUp model, and I was kind of surprised by my choice of materials because I don’t think it was as conscious. And I was like, whoa, I have a lot of Plexiglas and transparent foils and I wasn’t aware of it. So, it was a great opportunity to see those works together in one space and realize, oh, this is too much of that, or I don’t like this, or hey, this really works together. And one thing that you noticed, and Kunsthalle Wien’s artistic director Michelle Cotton noticed as well, is this relationship to scale, which I wasn’t aware of that much because I like making works that respond to spaces that they’re shown in. And that leads me to different scales. But I never had it all in one space, that’s something new that came up. In this show, time and space collide. Looking through the prism of time, I feel like my works hold up well in terms of content. What surprised me is how time has affected some of the materials I work with. For example, the metal coatings on some of the 3D printed statues have oxidized, and the print on the foil works has started to chip off in the ones that were not stored properly, this is why I had to reprint Things to Come. On the other hand, the videos and inkjet prints on paper (like Portrait [mesing] and the stacks, Untitled [30.lll.2010] and Untitled [Ivica Osim] ) still look fresh.

Audience Member: Seeing the works up there and hearing Carson talk about your early works, I was wondering, what is now your relationship to distributing and having your work available when you and a lot of artists of that generation use the internet as a platform to exhibit, show, present with quite a reach because your work has a lot of followers. Turbo Sculpture, on different platforms, was viewed a lot of times. And now you have also exhibited in a much more institutional context recently. I just wanted to hear maybe what were your thoughts through that history of yours, from using this platform in a very free manner, with no hierarchy and no authority of the institution, and being now in a more institutional context. And would you use a digital platform again to broadcast your work, and how do you feel about the new platforms, Instagram, TikTok and so on?

AD: Yeah, I do still use digital platforms, but it’s different now. Back then, the internet felt like this wide-open playground where you could just make things and throw them out there. It was exciting! We were working on big screens and now, it’s all small screens [gestures to phone]. That shift alone changes what kind of works are made. And let’s be real – the internet has gotten… messy. It’s super commercialized, heavily censored. Everything gets squashed into trends or formats that can “perform.” Art gets streamlined into what’s easy to scroll past or share. It’s harder to feel that same liberatory energy it had back then. But don’t get me wrong, it’s still an amazing tool for spreading images and ideas. The reach is undeniable – like Turbo Sculpture has been seen by so many people who’d probably never walk into a gallery. That kind of accessibility is huge. But how much freedom do you actually have to work authentically on these platforms? That’s the tricky part. I think the institutional context and platforms like Instagram, TikTok, whatever, can coexist, but they do different things. The question is, can we use these spaces without getting fully consumed by their rules?

Artist: Aleksandra Domanović

Exhibition Title: Aleksandra Domanović

Venue: Kunsthalle Wien

Place (Country/Location): Vienna, Austria

Dates: 5.9.2024–26.1.2025