Viktor Witkowski

On December 8th, 2023 the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Germany’s federal intelligence agency) classified the far-right AfD (Alternative for Germany) in Saxony as “verifiably extreme right-wing.” The same classification was extended to the party’s regional chapter in Thuringia. Since last summer, the AfD has led polls in Saxony, Thuringia, and Brandenburg by a wide margin. In the past few months, the AfD’s nationwide approval has slipped from 23% in January to 17,5% (as of May 1st), but it still comes in as the second-strongest party.

Even though the AfD enjoys its most substantial support in the eastern states of Germany, the party has a strong foothold in Lower Saxony, Hesse, and Saarland – all of which are in western Germany. In other words, the AfD relies on broad support across states and social classes that has roughly doubled since the last general elections in 2021. Political analysts offer various reasons to explain the AfD’s high approval rating over the past two years. From people’s economic concerns over inflation, high energy prices (which are tied to Russia’s war on Ukraine), a general shift to the right due to what was perceived as government overreach during the most acute part of the Covid pandemic, voter frustration with the established parties, to the consistent fear-mongering across party lines (most prominently by the right-leaning, conservative CDU/CSU) towards minorities and immigrant communities) – there is no shortage of assigning blame and giving potential explanations. When it comes to the geographic West-East divide in relation to the AfD’s popularity, no one individual argument is convincing. A look at the comparable political divisions in Poland and the USA reveal that the urban-rural fault lines provide some helpful answers. As recent elections in all three countries have demonstrated, people in rural areas are more likely to cast a conservative vote – especially when people in rural areas are exposed to fewer job and future prospects, lower income, social isolation, lack of health care services, and limited means of public transportation. In the eastern German states that were part of the GDR until its dissolution in 1990, rural areas have been plagued by scores of young people leaving for urban centers. No state has been hit by rural flight as hard as Saxony. In 2018, 78% of Saxony’s population was living in urban centers. According to a 2020 Economic Research Institute Dresden (ifo) study, the number of people living in rural areas in the states Berlin, Brandenburg, Saxony, and Hesse is the lowest since 1871 (and representative of a general trend across all of Germany). At the same time, far-right rhetoric and the promise to turn back the clock to an imaginary time when family values, gender, and national identity were clearly defined and abided by all has found its way into the minds of affluent and highly educated urbanites resulting in today’s high poll numbers for the AfD across social and geographic strata.

Journalist Peter Laudenbach published his book Volkstheater last year in which he chronicles verbal and physical attacks, threats, intimidation tactics, influence campaigns and official statements by the extreme right/AfD against artistic freedom. While Laudenbach mainly focuses on film, theater, music, and institutions working on remembrance and migration, his observation that the extreme right’s actions are a “declaration of war” on culture can be applied to contemporary visual art as well. In his book, he lists one example from 2022, when Neonazis would regularly show up for openings at the Kunstverein Zwickau with the goal of intimidating its visitors and organizers. An open letter signed by four directors of the leading regional art institutions, directed at the city’s mayor and asking for preventative action, finally put an end to this disturbing practice. And so the question is: are German cultural workers prepared for a sustained fight to prevent an extreme-right takeover of cultural institutions and their funding bodies?

There is not much reason for optimism if one looks at the most recent tribulations surrounding several embarrassing decisions to cancel exhibitions like one by Jewish artist Candice Breitz or to cut funding to the Oyoun Cultural Center in Berlin on the basis of alleged antisemitism. Meron Mendel, the Israeli-German director of the Anne Frank Educational Center in Frankfurt, is quoted in Monopol Magazine warning of an “anti-humanist trend in parts of the art and cultural scene” while also pointing out the threat to artistic freedom in the form of “instrumentalizing accusations of antisemitism.” If decision makers within the cultural sphere cannot distinguish right from wrong and what is morally reprehensible versus what is justifiable criticism, I am not sure that Germany is well-equipped to fend off the extreme-right’s takeover of cultural production. Without moral clarity, moral ambiguity and hypocrisy becomes the rule.

During my several visits to Warsaw between 2021 and 2023, local artists were not just concerned with or troubled by the possibility of a third term for the far-right PiS party (spoiler alert: PiS lost the general election last October). Their resistance was palpable and visible. Artists were engaged inside and outside their studios: participating in regular demonstrations for women’s rights, for the rights of minorities, the LGBTQ+ community, against new laws meant to further limit individual choices (this is when PiS, in 2020, passed a bill that imposed a near-total ban on abortions). When the so-called “migrant crisis” began in 2021 – an artificially created crisis orchestrated by Belarusian dictator Lukashenko with the Kremlin’s active support[1] that saw hundreds of vulnerable people from Africa, Syria, Iraq – with mostly Kurds and Yazidis – being flown into Belarus and bussed to the Belarusian-Polish border, artist friends travelled to the border for relief and rescue efforts. Once Russia started its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many artists helped to coordinate daily arrivals of tens of thousands of women, children, and elderly from Ukraine into Poland by distributing drinks, food, blankets, clothing, assisting them in finding housing, and providing other vital information.

Walking through Warsaw and visiting galleries, off-spaces, artist studios, and museums (at least the ones that were not under the control of the far-right ruling party yet), it was impossible to ignore how the threat of yet another term under PiS’ rule had galvanized artists and curators. Some of the work was overtly political, but the vast majority opposed the conservative value system laid out by PiS by addressing identity (gender and sexuality), the role of church and state, Polish history as seen through the lens of a generation born after 1990, the appropriation of classical avant-garde tropes to ridicule, criticize, innovate, reimagine and question the realities of 21st century Polish society.

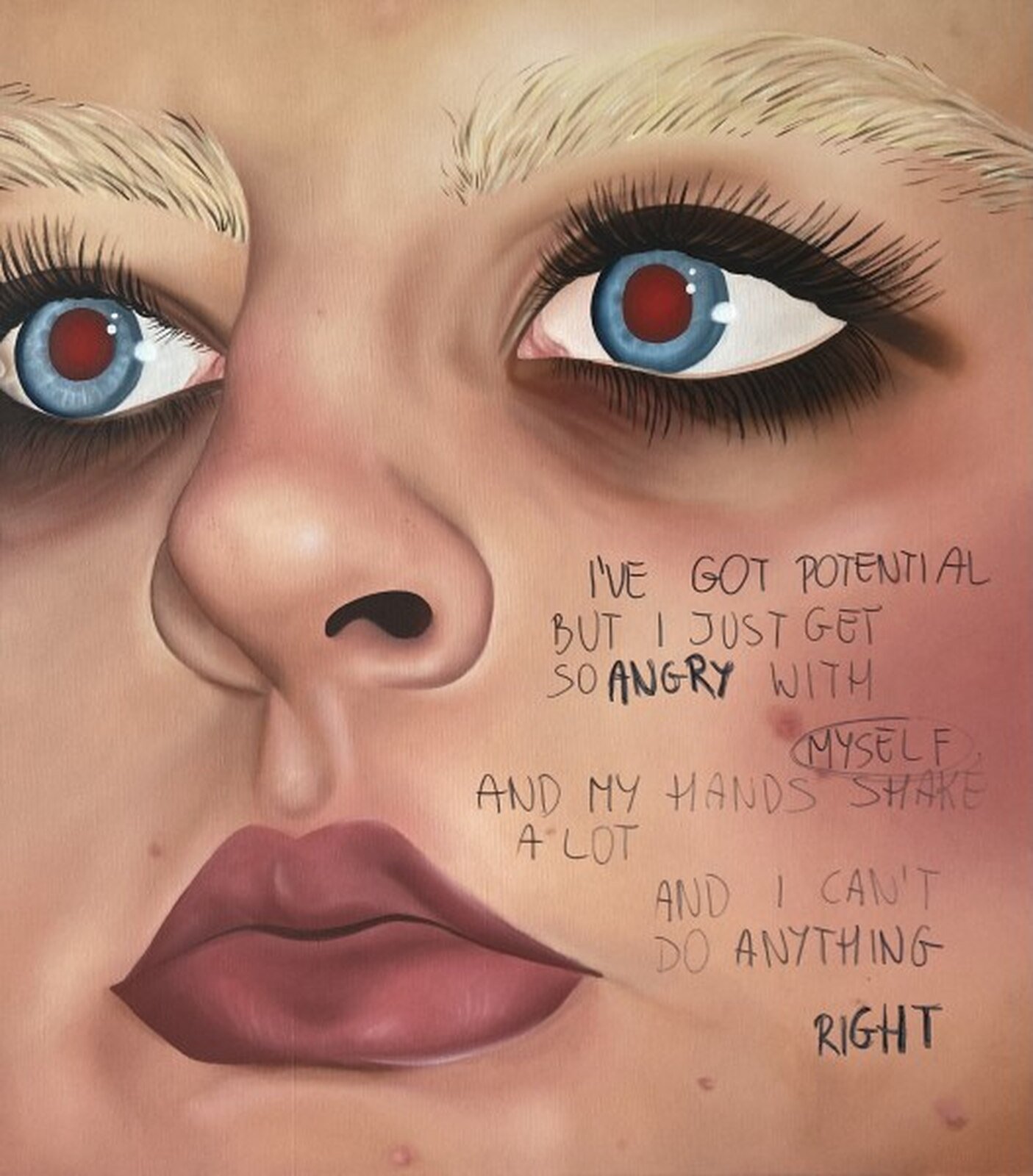

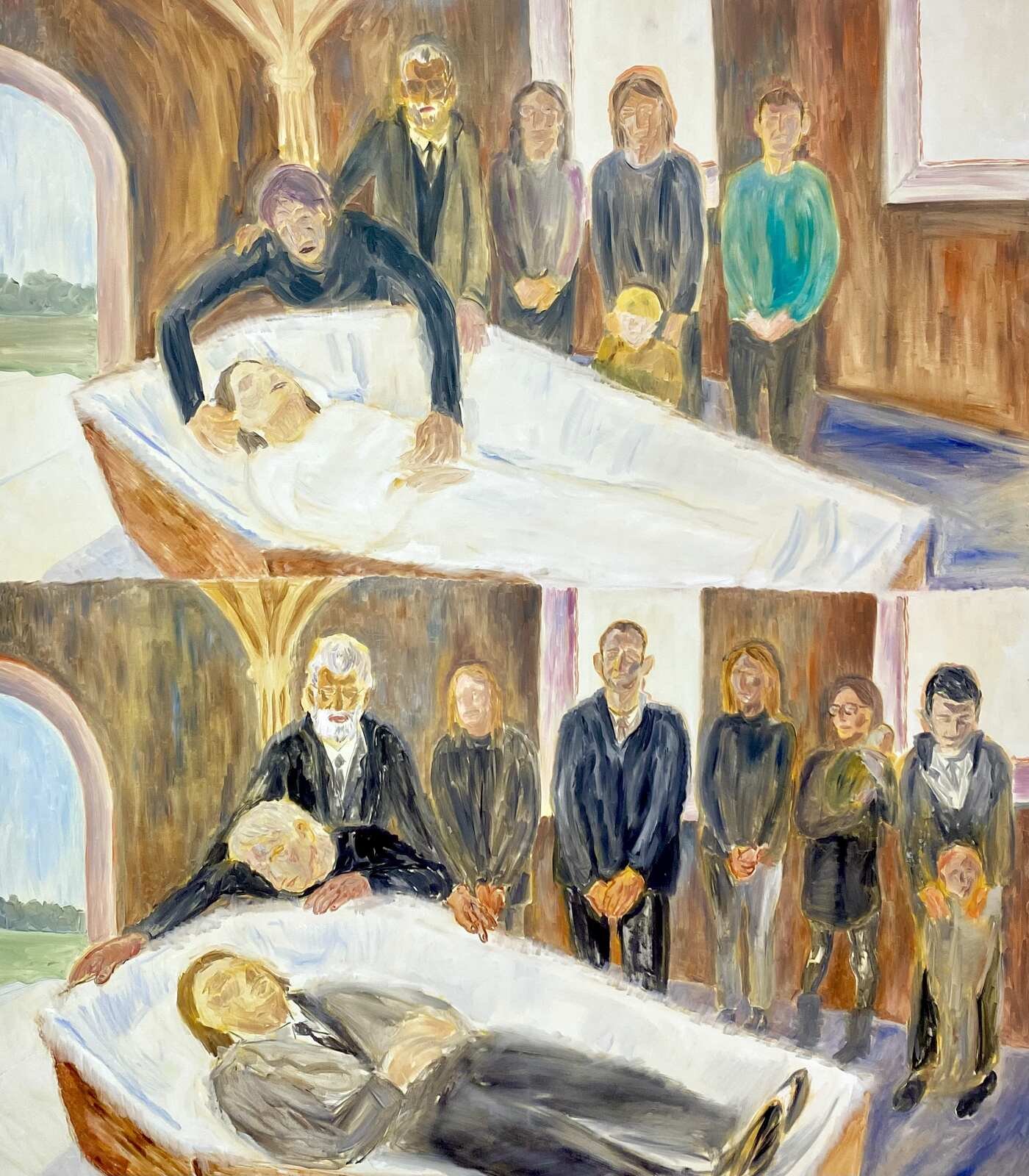

At the Zachęta National Gallery of Art, one of Poland’s most important museums for contemporary art, I visited the exhibition The Discomfort of Evening in 2022. This exhibition, curated by Magdalena Komornicka, featured young Polish art in opposition to an increasingly oppressive and Eurosceptic government. Painters like Kornel Leśniak and Patryk Różycki tackled the vulnerability of the self with Różycki paying attention to his rural upbringing and working-class background. While the ruling PiS party (in tune with the rhetoric of Trump and the AfD) proclaims to be representing and standing for the country’s forgotten rural population, Różycki’s paintings complicate this narrative and deliver an intimate portrayal of a family whose lives cannot easily be instrumentalized by a party or political ideology.

Another PiS (and again AfD) favorite is to direct constant attacks at the country’s LGBTQ+ community. Artists Kacper Szalecki’s and Sebastian Winkler’s work in this exhibition used their personal experiences as queer people living in conservative Poland to voice a mix of desire, pain, violence and anxiety.

Video artist Martyna Miller, on the other hand, showed animated tapestries of overlaid, nude bodies in constant motion; intertwined, sensual, yet never explicit. Within this symphony of the layered body her message is one of affirmation, self-love and love for others – both in flesh and spirit.

But the most harrowing and striking work that I encountered during my visit to this quasi-biennale of young Polish art were the paintings by Adam Kozicki. The subject of a series of works he produced that year was his detention and abuse at the hand of Warsaw’s police. In early January 2022, Kozicki was arrested by plain-clothes police and then held for a couple of days without access to his lawyer. While in detention, he was exposed to abusive methods that robbed him of his agency and basic human rights. As a result, his paintings have absorbed the trauma of those days. The fuzzy and erratic linework rendered with an airbrush on canvas traverses his surfaces while mapping out a world overcome by dread. Kozicki distorts the perspective of each setting, rendering it claustrophobic and collapsing his point of view with the viewer’s: his eyes become ours, his hand become ours, and as a result we suddenly find ourselves in Kozicki’s mind, unable to change or impact the given situation as long as we look at his painting.

If Germany wants to succeed in its fight against the AfD in a similar way that Poland dethroned PiS, the initiative has to come from the ground up. One such example in Saxony is Land in Sicht e.V. (Land in Sight), which is a donation and membership-fee based organization with the goal to fund projects in rural areas that aim at working with and educating communities on such topics as inclusivity, (anti)racism, diversity, and the relevance of democratic action – often through visual arts-affiliated projects and exhibitions. The initiators of Land in Sicht are Leipzig creatives such as painter David Schnell and ASPN gallery owner Arne Linde. A look at the list of their funded projects reveals that at the very least, Land in Sicht manages to unify a roster of various Saxony-based organizations (such as Tolerantes Sachsen, or Queeres Sachsen) with the goal of allowing them closer and more finely-tuned cooperation in times of great need.

When Saxons cast their votes in the state’s September 1st election, it will be each individual’s responsibility to do what they believe is right. But artists can and should do more. Our work assumes a public and is made for public viewing and consumption. And, with that privilege comes a responsibility: to acknowledge the times we live in and the darkness that surrounds us. This is not the moment to shun that darkness and continue as usual.

If we accept that the public we serve as artists, curators, gallerists, and museums is not the public we need to reach to effect any political change (since it is a small, self-selective and therefore non-representative segment of society), then we have to ask ourselves what public we wish to reach. And maybe the public we desire to reach needs to be the one we declare as subject and collaborator of our work instead of wishing it to become our target audience. In other words: instead of importing urban artworks to the countryside, we should be making work about and in the countryside – if that is the audience we wish to impact. It is also important that our “native” public, the so-called art world – may it be local, regional, national, or international – should be considered a public worth changing and expanding, especially since it has not been democratic or diverse since its inception. No matter what and who we wish to reach within or outside of the art world – artists and their practice are key to any meaningful and lasting changes.

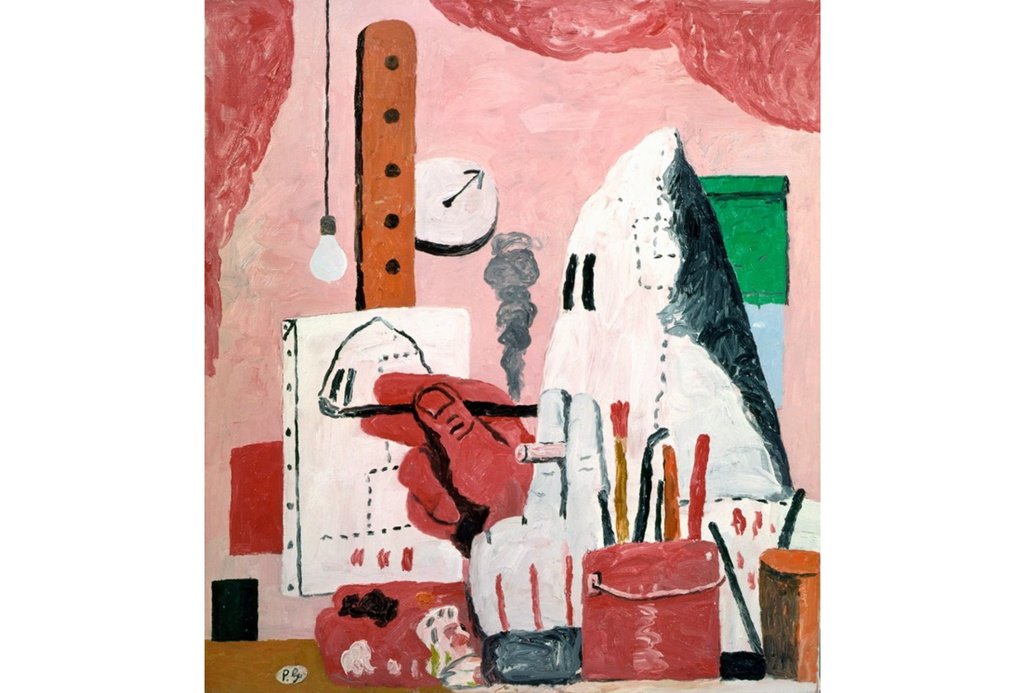

Artists who work with installation, video/film, performance, or across a range of disciplines, tend to be more adaptable and idea-based. Artists who work in more traditional media, such as painting, often prove to be less flexible and more process-based. But if we look at hard data in terms of sales and what types of artists get shown the most, the answer is: abstract paintings by white, male artists. In that sense, these artists have a crucial responsibility due to their heightened visibility on the art market. Maybe the example of Philip Guston is helpful to infuse some painters with much needed courage. Guston, who was the son of Jewish-Ukrainian immigrants from Odesa, is mostly known for his political commentary when he switched from making abstract paintings to figurative works. During an interview in the 1970s, Guston said:

“When the 1960s came along I was feeling split, schizophrenic, (…) The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into frustrated fury about everything—and then going into the studio to adjust a red to a blue.”

The degree of engagement, involvement, and participation in the social and political realities that I saw among Polish contemporary artists is generally lacking in their German colleagues. And I am also missing a sense of alarm and urgency for this turn amongst German artists.

Of course there are always exceptions in terms of individual artists and institutions in Germany. When I think of eastern Germany, the artist Sebastian Jung comes to mind, who describes his cross-disciplinary work as “populism against hate.” A few years ago, I visited an exhibition which included some of his drawings made at an anti-Covid demonstration that featured a mix of anti-vaxxers, populists, and people on both ends of the extreme spectrum. Jung travelled to this demonstration equipped with paper and a pencil (sometimes he takes photos, too), with the goal to capture what was unfolding around him. These drawn vignettes, rendered quickly on the spot, resemble cartoons (recalling a jittery version of South Park) that successfully express group dynamics at populist rallies dominated by anonymous heads fused together into one indistinguishable mass.

Sometimes the mass of heads and boneless bodies are replaced by more personalized individuals with arms and legs attached, holding up signs, flags, or showing off punchy slogans on their attire. Jung’s drawn reportage documents and dissects a movement driven by a deep desire to abandon truth in the name of free speech. In the end, neither truth nor free speech will survive this movement.

Institutions like the Oyoun Center, Hošek Contemporary, GfZK, Halle 14, or, to include one institution from Germany’s west, Marta Herford, have been consistently giving a platform to lesser known, marginalized narratives, histories, and people.[2] But these exceptions need to become more common in order to move the proverbial needle of arts and culture in Germany. One advantage of the Polish artists – and in no way is this a desirable situation – was living under PiS rule for two terms. PiS’s political program had become a reality permeating every-day life. In addition to their attacks on the cultural sector and labeling it an elitist passtime, PiS cuts to arts funding made institutions, galleries, off-spaces, and artists more reliant on their respective communities. In the case of Warsaw and larger cities which tended to be governed by the opposition, each municipality was able to provide some funding – but not to all in need and never enough. The creative community became more inventive and resistant the longer PiS remained in power and the more damage they caused. A similar fate awaits German cultural workers who will find themselves forced to make hard decisions once AfD representatives take more seats in regional councils and state houses.

Having lived in Germany half of my life, I am aware of the country’s limitations and possibilities. One of the biggest obstacles within the arts in Germany remains the underrepresentation of minorities. It is important not to put blame on institutions alone without mentioning the dismal situation in German galleries. Official numbers about German artists with a migrant background are hard to come by. The only reliable and extensive data-set I found was on the website of Kulturelle Bildung (Cultural Education). It contains a detailed breakdown and analysis of a study carried out by the Zentrum für Kulturforschung (Center for Culture Research) in 2011.[3] As of 2023, nearly 30% of Germany’s population is comprised of people with a migrant background (at least one parent is foreign-born or comes from a migrant family). This is a substantial amount of the entire nation. When we look at the numbers of students with a migrant background enrolled in German universities, the number drops to around 16% of the entire student body. According to these numbers, and without any official data, the percentage of students with a migrant background enrolled at art schools must be in the lower single digits. At the same time, the study by the Zentrum für Kulturforschung concludes that in interviews with participants, those that attributed most value to cultural events and exhibitions were second and third generation immigrants (they were more likely to visit museums, art exhibitions, and cultural events than people of German origin). All participants overwhelmingly expressed the need for more artists with a migrant background. After reading the results of this study, it becomes clear that German cultural institutions and galleries are sitting on a tremendous, unrealized potential to revitalize public perception and inclusion within German society (not to mention the financial benefits of integrating a large segment of society).

A glance at the AfD’s culture program, as investigated by Manuela Lück for the Heinrich Böll Foundation, reveals that its main goal is to rid the arts of “Multi-Kulti” (a derogatory way of saying multicultural) while strengthening what the party leadership calls “deutsche Volksgemeinschaft” – a late eighteenth-century term that describes a unified, homogenous national community and which was appropriated by the Nazi party in the 1930s to describe national identity based on race. Similar to other autocratic movements around the globe, these people say what they mean and they mean what they say. And they do so in plain sight. None of this is happening in hiding. Anybody can access and read the AfD’s official “program.”

My argument is that the current state of arts and culture in Germany makes it easier for the AfD to inflict serious and long-lasting damage. With fewer minorities represented in the cultural sector, the AfD will have less work to do and will encounter less resistance to achieve its goal of a new artistic Volksgemeinschaft. And any changes implemented by the AfD will therefore be marginally visible or noticeable to many artists. It is unlikely that the current favorable numbers for the AfD in Saxony and Thuringia will change much until the September elections. The worst possible outcome for the party will be a second place in all three states. Galleries and institutions that provide artists with visibility have to encourage them to respond to this new threat while seeking out artists who have not been seen or heard yet.

A diverse community is more resilient. And artists have to acknowledge the new realities that await under an empowered AfD. The artist’s studio must not be a refuge from the world, but a place of resistance. That resistance can be subtle, you do not need to wave a flag or stand in the streets. Just allow your work to reflect the changed conditions outside of yourself. And if you still believe that politics has no place in your work, know that art does not exist in a vacuum. If the studio becomes sealed off from its external political conditions, it will become a place of self-censorship. The cultural warriors of the AfD will delight in art that for the sake of a universal appeal, avoids addressing politically and socially controversial topics. To paraphrase Hannah Arendt’s observation on what enables totalitarianism: it is not what our enemy does, but what our friends do.

[1] https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/09/18/russia-belarus-poland-lithuiania-migrants-eu-weapon/

[2] The exhibition “There Is No There There” at the MMK in Frankfurt am Main which runs through September 29th of this year, brings together artists who either came to Germany in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s via grants or as “guest workers.” In this exceptional exhibition, many artists are shown for the first time alongside their peers with a similar history of migration and who document a still divided Germany and the crucial role immigrant communities played for Germany’s nascent economy after WWII.

[3] Another more recent study, available for download on the Deutscher Kulturrat’s website (The German Cultural Council), takes a close look at diversity in German cultural institutions from 2018-20. One focus of this study is the overall percentage of people with a migrant background working in these institutions which the Kulturrat estimates to be 18%.