Raluca Oancea

In the context of the cultural program Timișoara 2023 – European Capital of Culture, the fifth edition of the Art Encounters Biennial of Contemporary Art presented this year an experimental curatorial solution in which a group of young curators who are active on the scene in Bucharest, Cluj, Timișoara and beyond – Cristina Bută, Monica Dănilă, Edith Lázár, Ann Mbuti, Cristina Stoenescu and Georgia Țidorescu – weave together rhizomatically with Adrian Notz, director of Cabaret Voltaire (Zurich). The collaborative formula, the dynamic nature of the project, the capacity to contaminate artist-run platforms in the city (Avantpost, Balamuc, Baraka, Lapsus, Nava C2, Simultan) as well as unconventional exhibition spaces – Timișoara’s tram depot, the Faber workshops, a warehouse near Mega Image or the Cinema Victoria – evoked the accomplishments of the Indonesian collective ruangrupa at documenta 15 (2022). There was strong connection to the broader art scene, alongside dynamic and inclusive events such as the previously mentioned documenta 15 and the previous edition of the Venice Biennale, The Milk of Dreams. Thematically, the Art Encounters Biennale engaged current directions of international artistic research, which included the post-medium affect, the posthumanist critique of the Anthropocene, the relationship of art to nature via technology, and the imperatives of the experimental scene such as care, collaboration, inhabitation, and the creation of human and non-human connections.

© courtesy of Zenoviu Haiduc Collection, Cluj-Napoca

All these directions are also suggested by the title of the biennial My Rhino Is Not a Myth: art science fictions, a title that brings to mind the 16th-century appetite for visual art, science, and magic, as well as the intimate communication that existed between the fields of art and science, specifically that of hermeticism and alchemy. The aim of the biennale was to stage a revival of Dürer’s Rhinoceros and the pre-Cartesian interpretation of the world, which implies both the liberation of truth and science itself from the grids of positivism and abstracted rationalism, as well as a reevaluation of the body that regains spiritual, magical, and vital (biological) connotations in consequence. In this context, the meaning of the term “science” must be interpreted more from a phenomenological point of view, in the sense of humanization and a return to the everyday world, to “things themselves,” as well as in the sense of placing the thought in an indissoluble link with affect and corporeality. The cold and sterile scientific perspective associated with the third person will thus be replaced by a warm, first-person view and abstract rationality by a free, concrete phenomenological description akin to poetry.

As an imaginary object, Dürer’s Rhinoceros, a drawing of an animal that the artist had not been able to see with his own eyes, raises the phenomenological question of “intentionality” and the precedence of meaning. Can I really see what I do not know? Can I see a “rhino” if I don’t know what a “rhino” is? What does the act of seeing entail? What is the relationship between what is “seen” and the seeing eye? In the phenomenological sense, art is the best response to all these questions. It is an aesthetic pleasure, and nowhere else do we feel the primary delight of the simple act of seeing, the amazement given by the things that appear near us, by the colors that instantly change our mood. Merleau-Ponty, phenomenologist of perception and the body, pointed out that the invisible richness and depth of the visible is much better captured by the artist’s colors, rather than by “the philosophy that paints in black and white.”[1] This thought also suggests that old engravings, such as Dürer’s Rhinoceros, or Melencolia, represent a particular kind of philosophy in pictures. In this context, I will take a phenomenological approach to each of the four projects in the exhibition My Rhino Is Not a Myth: Anticipations and Sighs, Broken Cyphers, Carriers of New Seeds, and Streams of Navigation.

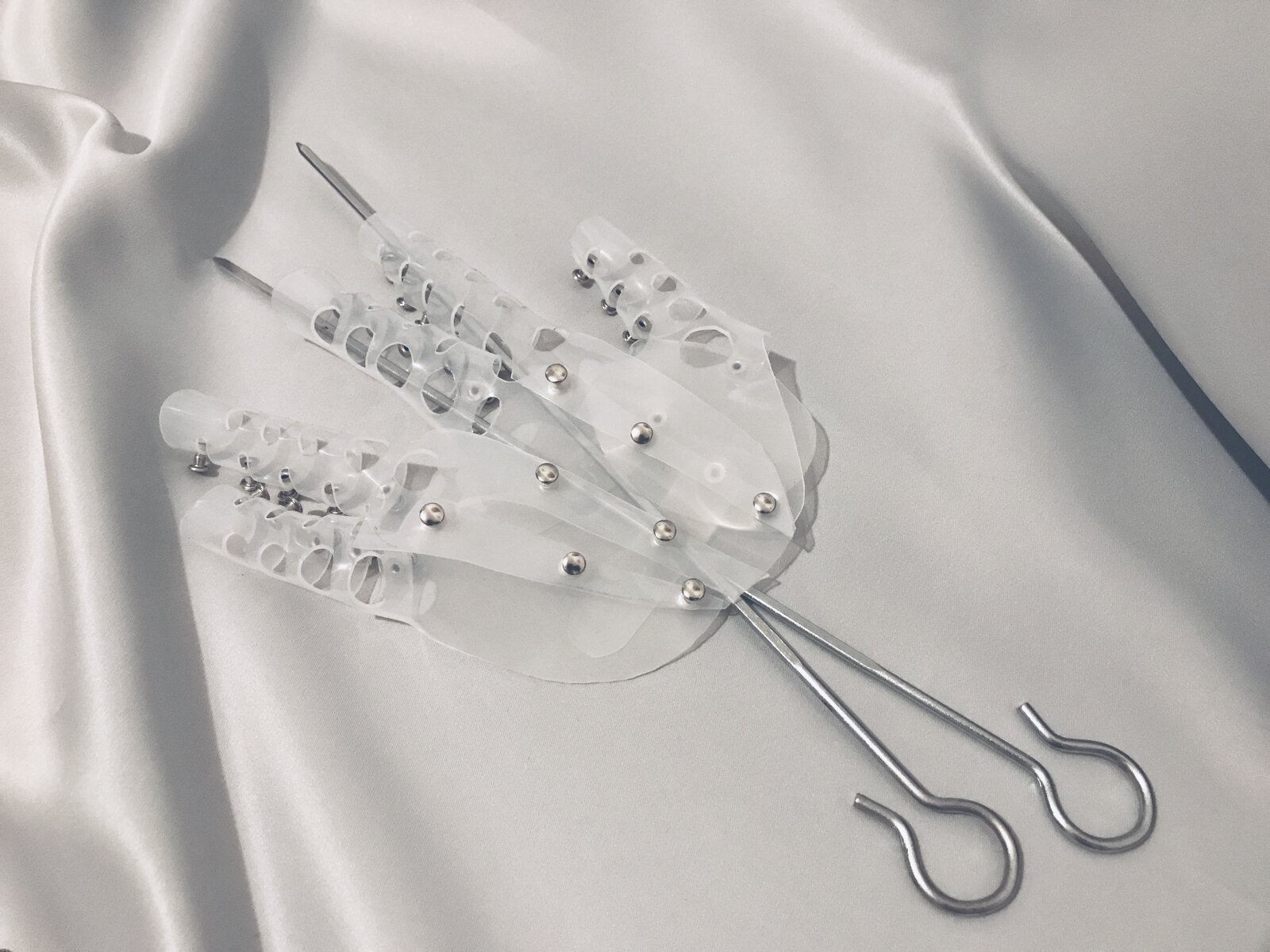

From the first part, Anticipations and Sighs, in order to follow the theme of perception and the body, we chose Giulia Crețulescu’s works, in particular, Riding a Speeding Vehicle under Hypnosis, a series of handmade objects that follow the ergonomic design of race car seats, and respectively the Membrane series – consisting of translucent objects made of white, light silicone that reinterpret the shape of essential parts of the human body: a hand, a face. It is no coincidence that the objects in the first series: textile structures made of a shiny grey, sturdy, and flexible material, are mounted vertically on the wall. They resemble the human silhouette, which lies between the two poles of existence: the transgressive one – the angel wing – and the prisoner – the straightjacket.

Today, we find ourselves in the age of perfect design, of fulfilled functionality, of hyper-progress for the sake of progress, which forces modern man to maintain the same machine rhythm; an age in which the phenomenological analysis of the “man-object” and authentic work, pioneered in the middle of the last century by Heidegger or Merleau-Ponty, must be taken up again on new premises, and why not by artistic means. In this respect, Giulia Crețulescu’s objects tackle in Object-oriented ontology (OOO), the relationship between being born and being built, between the natural thing, the tool, and the work of art, as well as between the subject and its world.

The race car, symbol of speed and human augmentation, brings into question the transition from modern hybris, fueled by new possibilities of transcending space and time, to the anguish of the postmodern individual for whom this superhuman pace and ubiquity become painful. We are stuck in this paradigm of hyper-reality (as defined by Baudrillard), hyper-speed and performance, the paradigm of fast food, fast art, fast self, etc., in which paradoxically, as Mark Fisher remarked, the future refuses to arrive.

Robbed of time and the possibility of living, of his once authentic, durable things, modern man finds himself a slave to plastic and consumer goods, trapped in the flow of media affects. In a last attempt to put anguish and finitude behind them, the body tends to automate itself, to grow a new, more resistant skin. Starting from the definition of the “living body,” of the vulnerable human body which, according to Merleau Ponty, “is present when, between the see-er and the visible, between touching and touched, between one eye and the other, between hand and hand a kind of crossover occurs.”[2] In short, when “the spark of the one who feels sensitively ignites,” Giulia Crețulescu asks herself if the machine-becoming of man can mean anything other than the death of the spark, other than the detachment from the organic?

Placed at the crossroads of the organic and futurology, her artificial skin membranes and angel wing-like seats speak to the vulnerability of the living body, its finitude but also its freedom to rise above mathematical functionalism, to demand its own time, disconnected from the linear time of work, production, capital. These objects, which, despite their futuristic designs, are crafted by hand, quietly and carefully, fighting for the right of things to have a story, a past, and a future, a living body. Once placed in a gallery space, they relinquish their function and speed and are recharged with a “spark,” with aura. The hybrid, futuristic appearance of the wing-chairs, of the silicone mask with metal rivets, of the hand augmented with aluminum rods, speak rather of a de-territorialization of the body, of its liberation in terms of overcoming the normalization of the face, the standardization of gesture, culminating in the transcendence of the anthropocentric paradigm itself. Machine-becoming is thus defined not as a surrender of the organic but as leaving behind the rigid concepts of man, subject, object and replacing them with the more supple concepts of agent (Latour), chiasm, living body, and flesh (Merleau-Ponty).

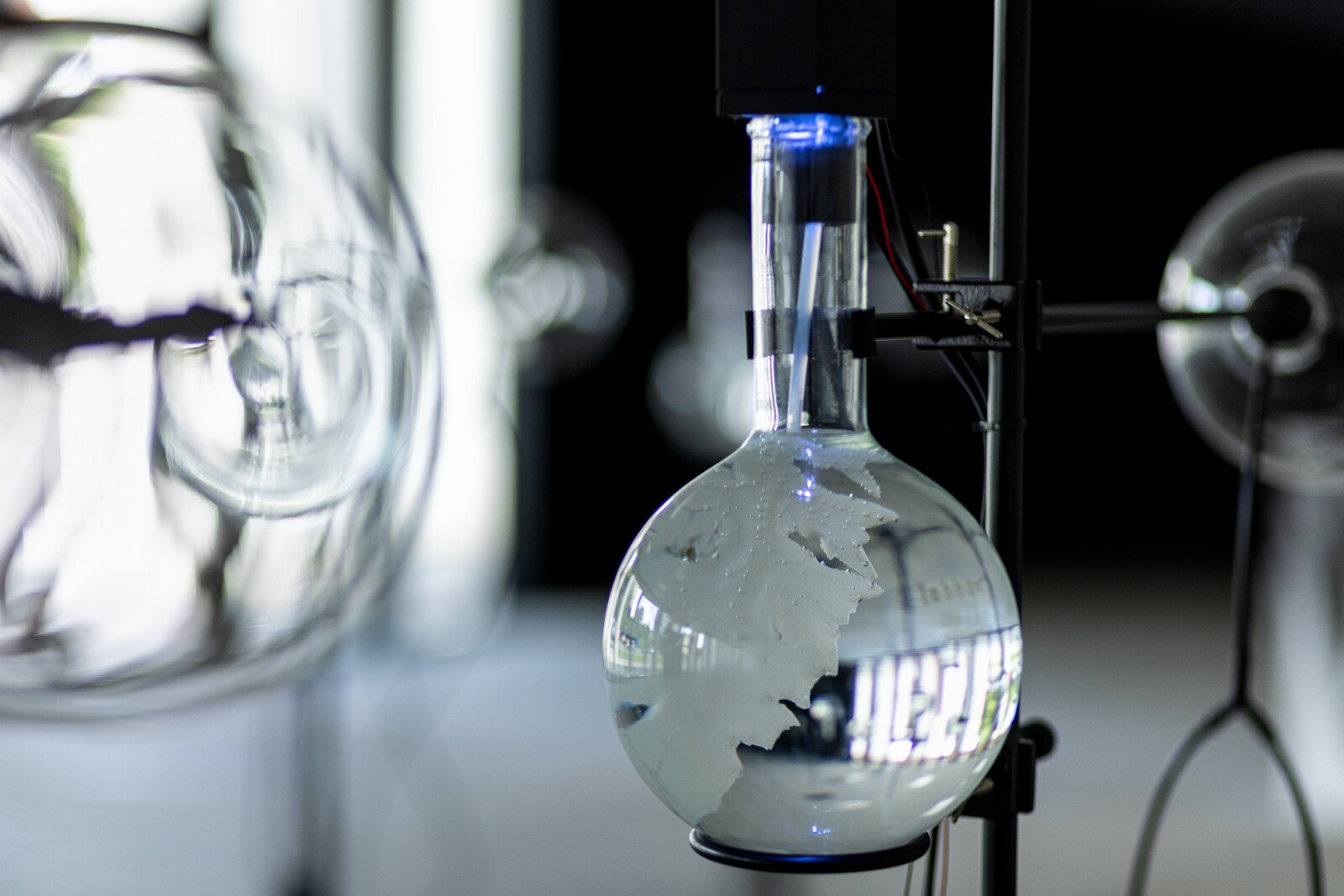

In the same sphere of bringing out of hiding new connections, new functions, new scenarios about the world is Sensitive Dependence, the work of Floriama Cândea, a painter who gives up color to focus on subtle exercises of technological appropriation of movement, breathing, flow, duration. The installation involves a series of transparent glass globes housing hybrid plants – white leaves with fine silicone veins and compact black flowers – that can be activated by human touch. To be more specific, using an assemblage of pulse oximeters, cables, and Arduino boards, Sensitive Dependence converts the viewer’s heartbeat into a flow of vegetal energy which enlivens these plants, making the white leaves pulsate and the flowers breathe like lung tissue trapped in a pleura of black cloth.

It is important to note that the origin of these entities is the so-called decellularization process, used in biomedical engineering to separate the extracellular matrix of a tissue (ECM) from the cells it hosts. In other words, Floriama Cândea’s fine silicon ribs convey the idea of a decellularized leaf that mimics only the formal matrix of the body, composed of white, almost translucent connective tissue. Interestingly, this biological framework on which bodily functions are based brings us paradoxically close to what Aristotle would have called the “form” of the leaf. We must admit the power of art to propel one unexpectedly into a twilight zone where the metaphysical touches the biological, the human returns to the vegetal (see also the unexpected structure of the upside-down tree lung), and the plant-becoming (Deleuze) seeks the idea (Plato).

All this, plus the tendencies of sublimation and fusion of opposites (motion-rest, air-earth, invisible-visible) and the choice of non-colors (black, white), foreshadows a new kind of philosophy through Cândea’s approach. A hybrid, non-discursive philosophy that replaces categories and words with visual forms and signs that can be placed somewhere between Deleuze’s “cinema-thinking” and Merleau-Ponty’s “painting-thinking”. In this context, the artist’s focus on rethinking the intricate network of the world, on rearranging the species and genres of Being based on new affinities and continuities of the visible and the invisible, lines up perfectly with Merleau-Ponty’s ontology (“any theory of painting is metaphysics”), putting into action the philosopher’s demands: “The whole description of our landscape and the lines of our universe, and of our inner monologue, needs to be redone. Colors, sounds, and things – like Van Gogh’s stars – are the focal points and radiance of being.”[3]

Floriama Cândea’s cyborg plants, placed at the intersection of the natural and the artificial, of reality and virtuality in a world of differences and affinities, avoid any age-old classifications and norms. They propose rethinking the world beyond genres and species, following new categories and “focal points”(Merleau-Ponty) belonging to art (shapes, sounds, colors) and everyday life (things, technologies). However, transcending hierarchies and taxonomies isn’t possible unless a preliminary interrogation of the hidden codes and unexamined presuppositions at the root of every historical worldview is undertaken. This brings us to the main line of inquiry that the Art Encounters curatorial team attaches to Broken Cyphers, the section where we find Sensitive Dependence, and a real phenomenological stake.

Cândea introduces a new type of ontology: visual, capable of understanding hybrid, natural-technological ways of existing. To overcome the solipsisms and dichotomies that have isolated man from the world and its things, this ontology first follows the classical phenomenological premises of reintegrating man into the world and reclaiming things as things. Things, as key elements, will be redesigned beyond the rigid functionalities of the anthropocentric perspective from within the new technological rhizome – the IoT (Internet of Things). This new web of the world, linking smart devices but also biochipped animals or humans augmented by heart monitors, expands the human form towards the machine-becoming and simultaneously redefines work as an agent capable of interacting and transmitting data autonomously. In this case, technology questions our capacity to act upon the world, to transform plants and things into our own bodily extensions. Revealing the constant exchanges and negotiations between man, art, and nature, it plays the role of a mediator that monitors our physiological states, gives the sculpture a living body, and synchronizes man and artificial nature with a breath.

The third work, Pteridophilia, a hypnotic video installation that explores eco-queer potential by merging erotic connotations with critical assertions about the Anthropocene, succeeded in inspiring strong emotions of admiration and revolt in the audience, climaxing with a visit from the Timișoara police to the exhibition space. The project belongs to the artist Zheng Bo and extends the thematic-aesthetic axis of their work at the Venice Biennale, Le Sacre du printemps (2021), a slow, upside-down projection aimed at the depersonalized union of young people with slender tree trunks. The new work brings together six young people in a forest of ferns, plants that are highly valued by Taiwan’s indigenous people but not by nationalists or Japanese colonizers. The set design involves a three-screen installation with cushions and natural ferns scattered among them, inviting viewers to come closer and touch them.

In the exhibition catalog, Zheng Bo, who is part of the Carriers of New Seeds branch of Art Encounters, presents themselves as a social artist who migrated towards environmentally friendly practices in 2013 when they claimed as their artwork a patch of grass in the old Shanghai Cement Factory that was to be leveled by bulldozers. Since then, they have been visiting Taipei’s forests to watch the explosion of giant, free-living ferns, including the bird’s-nest species, Asplenium nidus, known for its habit of climbing trees; soaring skyward, feeding directly from the air on raindrops. In the forest, the air is purer, the mind becomes sharper, and the body more agile. It is also in perpetual motion, gathering dimensions, becoming denser and denser as animals (human and otherwise), ferns, trees, stones, and earth intermingle. Sexuality “spreads like a scent from the bodily region it inhabits in particular,” conferring ambiguity and tension, displaying its spatial, atmospheric valences (Merleau-Ponty).

Of course, Zheng Bo’s artistic perspective on space is a qualitative one. Clearly diverging from the quantitative interpretations of space measured by a scientist, abstracted by a geometrician, it instead approaches the phenomenological perspective of lived, experienced space. The artist’s films thus conceal twilight zones – zones in which humans and plants become hard to distinguish. In this context, Pteridophilia stages an affective space, a color-space guided by the plurality of green shades that invoke the will to live, the Freudian Eros as the principle of life that is indivisible from the principle of death. Zheng Bo’s choice never to raise the camera to the sky can, therefore, evoke the feeling of a prison space, without horizon, i.e. escape. The green prison gives the impossibility of separating Eros from Thanatos.

The choice to reshape the space, the world, starting from a simple color, was interpreted in Deleuze’s writings on cinema based on the color-image, a subspecies of the affective image, which is not just a colored image, it does not refer to the color of one object or another but is an absorbing power that swallows up portions of the scene, rearranging the space and generating affect. The same choice puts into action Merleau-Ponty’s urge to reorganize the axes of the universe according to concrete points of reference (things, colors). Pteridophilia, in this sense, is defined as a unique visual ontology of similarity, linking the soft green of the leaves to the youth’s glowing skin and the light-dark circles under the eyes, the sap-filled branches to the veins of the arms swollen with effort. We recognize a transposition into the cinematic language of Merleau-Ponty’s famous passage revealing the power of a shade of red to link flower petals to women’s dresses, cardinals’ cloaks to revolutionary flags, and further to connect hues with textures (metallic, fluffy), progressing to the final cartography of depth and the invisible richness of the visible.

Depicting these immersive encounters, and immersing oneself in the greenery that looks back at you, Zheng Bo’s films launch a phenomenological analysis of the very act of seeing, where seeing means “entering the universe of beings that show themselves,” “to come to inhabit them and to observe from within them all other things” (Merleau-Ponty). Also, useful here is the concept of reversibility that Merleau-Ponty grounded in the artistic experience of Cézanne and Klee and the uncanny feeling of being looked back on by the trees you paint. The uncomfortable sensation for which man generally avoids exposing his body is given by the fixed gaze of the other, which causes a kind of colonization of the body that is taken in possession, deprived of itself, and reduced to the position of a slave. A similar feeling is felt by the young people moving naked, vulnerable among the ferns. To be close to plants to the point of falling in love, to allow oneself to be looked at, requires both adherence to an exchange of roles and an understanding of that deep reversibility at the level of being, where, to see means to be seen, to have a body means to become the object of the gaze, of the desire of the other, but also to possess the power to subjugate the viewer, to overturn the master-slave dialectic.

We can thus conclude that Zheng Bo’s eco-sexual films approach sexuality in a phenomenological manner, seeking a metaphysical meaning for desire and denouncing its incomprehensibility if “we treat man as a machine driven by natural laws, or as a bundle of instincts” (Merleau-Ponty). The phenomenon of eroticism returns the tension of existence that aspires to another existence without which it would not sustain itself, to the structural ambiguity of the body that includes the bivalence of object-subject, master-slave, to the transcendent courage of coming out of the skin, of spilling out into the human or non-human other, into the flesh of the world. We can thus read both the custom of archaic cultures to eat the flesh of spiritual animals to grow spiritually, and the practice of Taiwanese populations to eat the plant flesh of the fern Asplenium nidus.

The active role of the ferns, which become spiritual guides and fascinating bodies that annihilate the will of human power, increases their importance to the indigenous community and combats the indifference of the colonizing Japanese. When interpreted through a political lens, this relationship creates a dialectic that overturns the colonizer-colonized relationship in both the human and the broader living realm. Here, man’s relationship with plants is rather centered on the Taoist concept of wuwei, which does not imply simple non-action but rather a subtle taking care of and “letting be” – things that Western culture has much to learn from.

Sebastian Moldovan’s project POST WORLD UNDERCOVER GUERRILLA FAKE ROCK MANUFACTURING FACILITY INSTALLATION is a subversive attempt to dissociate itself from the imperatives of Western aesthetics centered on auctorial function and the production of (whole, valuable, pleasure-generating) objects. As with other projects developed by the artist, the approach is a processual one, with the space itself at stake; a site-specific intervention that took shape from the impressions and reactions generated by the location: the tram depot in Timișoara. In the same way, the project is an experiential and collaborative one, realized in partnership with Lucia Ghegu and Albert Kaan who, together with Sebastian Moldovan, spent more than a month in the space, living and working together.

Their story is simple: a group of people take refuge in an abandoned industrial area to manufacture paper stones, pondering the meanings that time, space, and life itself can still hold in the empire of the Anthropocene and the Post- prefixes. The uselessness of paper stones frees them from the regime of utilitarian functionality, giving them an uncertain status as hybrid objects placed somewhere between a natural thing and a work of art, qualifying them, at best, as instruments for measuring the passage of time. Here we can recall Borges’s story, The Immortal, in which people once confronted with the poisoned Pharmakon[4] of immortality cease to be animated by the inevitable enthusiasm of the finite, and slowly sink into stillness, turning into stones. As well, the metallic “stones” wrapped in rags, which opened the path for Tarkovsky’s characters in Stalker, through a metaphysical rather than topographical route through the uncertain chimerical “Zone” of life.

The tracing of a path, the creation of a route to follow, and the production of a space accompanied by special operating rules is, in fact, the aim of the three artists in POST WORLD UNDERCOVER GUERRILLA FAKE ROCK MANUFACTURING FACILITY INSTALLATION (as certified by the direction of this section of the biennale, Streams of Navigation). Thus, as soon as they enter the depot, the viewers of the installation notice the presence of a thin wire electric fence, frightening and fascinating at the same time, which will guide them uninterruptedly as they walk through the vast space, divided into three halls, whose structure and homogeneity have been altered using mirrors. Somewhere in the middle, the space conceals a dense area: it is the necessary journey through a tram turned into a tuning fork and bait for paranormal phenomena. In this zone of flashing white light, marked by the presence of a two-dimensional body made of layers of transparency and iridescence, we listen to experimental music, which is amplified by the body of the tram, whose metal casing functions as an acoustic guitar, a recording device for paranormal entities, and a corridor connecting to other time zones and travelers.

Another way of working with the space is through the subtle inclusion of small-screen videos hidden along the route. In these short films, a character in a blue jumpsuit performs repetitive gestures that simulate work, rest, or even levitation. One of the tablets on which the videos run is hidden in a grey metal box, which may once have concealed a control panel. To see it, you have to lean a little to the right of a small hole in the box, now adorned by the artists with a cheap veil-like curtain that was fashionable in socialist apartments. Note that all these interventions start a game with spatial directions and conventions – up-down, inside-out – bringing space itself into presence and adding new dimensions to it. The route thus recaptures the space inside a box or an abandoned sewer, and the space above or below the tram reactivates the inaccessible area behind the old machines where the eye now reaches with the help of a mirror.

In the last part of the hall, the industrial space merges into the natural sphere. In a metal cabinet, we see a series of sketches and instructions on the growth of plants that reveal the artists’ interest in renegotiating the human-nature relationship. On a low table, next to a few stones, we discover a pile of sprouted potatoes, both alive and dead, unsuitable for eating, for “consumption.” The light streams in through a high window with rusty latticework. One can finally see outside, where an explosion of ivy and other wild strains is taking place. Through a broken hole, the vegetation even managed to get inside. We feel that this exercise of creating and arranging space, an affective space, immeasurable in Cartesian axes and coordinates, is coming to an end. Inside becomes outside and, as phenomenologists have shown, there is no distinction between inside and outside, between consciousness and body, and between body and world. The body is everything; the body is me, the body is alive, it sees and, at the same time, is visible; the body is in the world. My body stretches to the edge of my gaze, swallowing slices of the world. We finally understand the meaning of Merleau-Ponty’s statement, that our glances are not “acts of consciousness” but “openings of our flesh which are immediately filled by the universal flesh of the world.”[5]

Translated by Camelia Diaconu

[1] Merleau-Ponty, Signs, trans. Richard C. McCleary (Evanston:Northwestern University Press, 1964), p. 22

[2] Merleau-Ponty, „Eye and Mind” in The Merleau-Ponty Aesthetics Reader. Philosophy and Painting, ed. Galen Johnson, Northwestern University Press Evanston, Illinois, 1993, p. 125

[3] Merleau-Ponty, Signs, trans. Richard C. McCleary (Evanston:Northwestern University Press, 1964), p. 15

[4] Pharmakon is Plato’s term, in Greek means charm, with a double meaning: as a medicine or as a poison

[5] Merleau-Ponty, Signs, trans. Richard C. McCleary (Evanston:Northwestern University Press, 1964), p. 16

Artist: Nora Al-Badri, Carlos Amorales (satellite program in MNAC, Bucharest), Korakrit Arunanondchai, Zheng BO, Floriama Cândea*, Anetta Mona Chisa*, Alina Cioară*, Ioana Cîrlig, Giulia Crețulescu, CROSSLUCID, András Cséfalvay, Chiril Cucu, Stoyan Dechev, Rohini Devasher, Megan Dominescu, Nika Dubrovsky, Albrecht Dürer, Arantxa Etcheverria, Constantin Flondor, Kata Geibl*, Anna Godzina, Liat Grayver, Veronika Hapchenko, Libby Heaney, Eugen Ionesco, IRWIN, Maren Dagny Juell, Zhanna Kadyrova, Hortensia Mi Kafchin, Patricia Kaliczka, Knowbotiq, Natasa Kokic, Alicja Kwade, Kazimir Malevic, Sakib Rahman Mizanur*, Gregor Moebius, Sebastian Moldovan* (with guest-artists Lucia Ghegu and Albert Kaan), Farah Mulla, Anca Munteanu Rimnic, Ciprian Mureșan, Museum of Antiquities, Sahil Naik*, Maria Nalbantova, Janiv Oron, Christodoulos Panayiotou, Katarina Petrovic*, Pushpamala, Cristian Răduță, Aparna Rao & Søren Pors, Tabita Rezaire, Naomi Rincón Gallardo, Pipilotti Rist, Dimitar Solakov*, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, Sasa Tkacenko, Kata Tranker, Vitto Valentinov, Mihaela Vasiliu (Chlorys), Sorina Vazelina*, Christian Waldvogel. (*new commissions)

Exhibition Title: Art Encounters Biennial 2023, My Rhino Is Not A Myth

Link: https://2023.artencounters.ro/en/home_en/

Venue: ISHO, FABER, Isho House / Art Encounters Foundation, Timișoara Garrison Command, Castle of Huniade Timisoara Art Museum, MX – Workshops (The S.T.P.T. Workshops)

Place (Country/Location): Timișoara, Romania

Dates: 19 May – 16 July

Curated by: Cristina Bută, Monica Dănilă, Ann Mbuti, Edith Lázár, Adrian Notz, Cristina Stoenescu, Georgia Țidorescu

Graphic design: Graphic Design Promotion Materials- Ștefan Lucuț, Graphic Design Mediation Program – Bogdan Matei, Web Development- Harald Singer, Graphic Design Catalogue – Stefanie Preis