Lovre Mrduljaš

Work-life balance is often presented as a matter of choice: a question of boundaries, smarter scheduling, or increased flexibility. Yet under today’s conditions, the personal rarely exists outside the professional. In The Accursed Share (1949), Georges Bataille observed that modernity recognises glory only insofar as it produces measurable utility – luxury is justified only if it proves useful. Bataille described this as a moral conditioning, a structuring of values where even leisure is measured against its usefulness[1]. That logic now extends everywhere: rest, social life, and personal time are accounted for, optimised, and absorbed into the metric of efficiency and return on investment. Balance is thus a phenomenon we might no longer possess.

These conditions force us to live with a nauseating dilemma: you can work anytime you want, but there is no wage if you are resting. Mike Pepi calls this asynchronous labour, an administration of time in which apparent flexibility conceals a continuous demand for self-management. Workplace benefits like flexible schedules or hybrid positions promise autonomy, but expect availability, productivity, and responsiveness beyond the nine-to-five[2]. A worker’s fatigued stupor on the commute home once carried the promise of rest at the destination. Yet this promise no longer holds when work can resume at any moment. Once a retreat, the home has become a prosthesis of the workplace: screens, notifications, and digital infrastructures extend the demands of labour into the fabric of domestic life. Our dilemma is wicked, one where fatigue may have become a condition of participation.

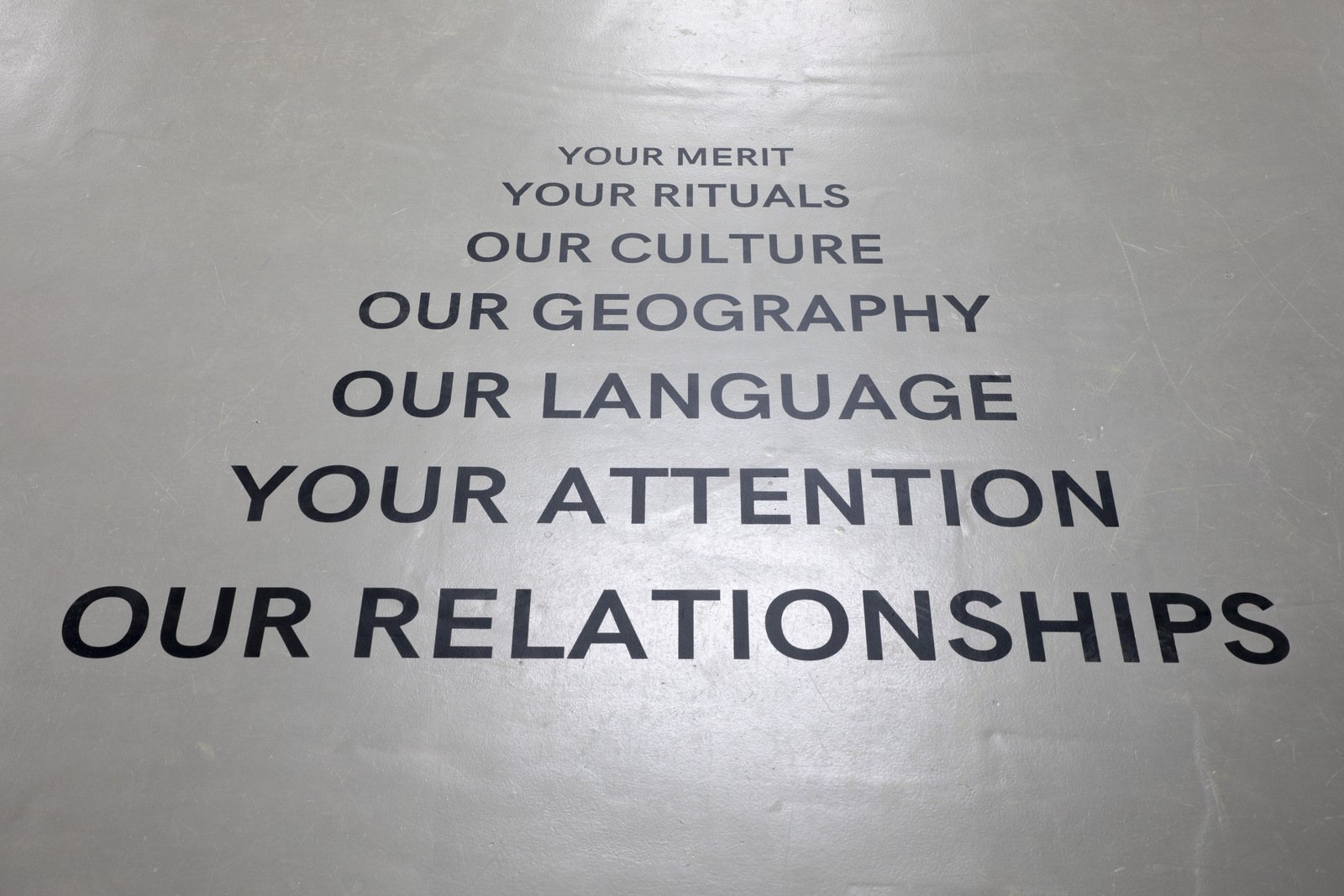

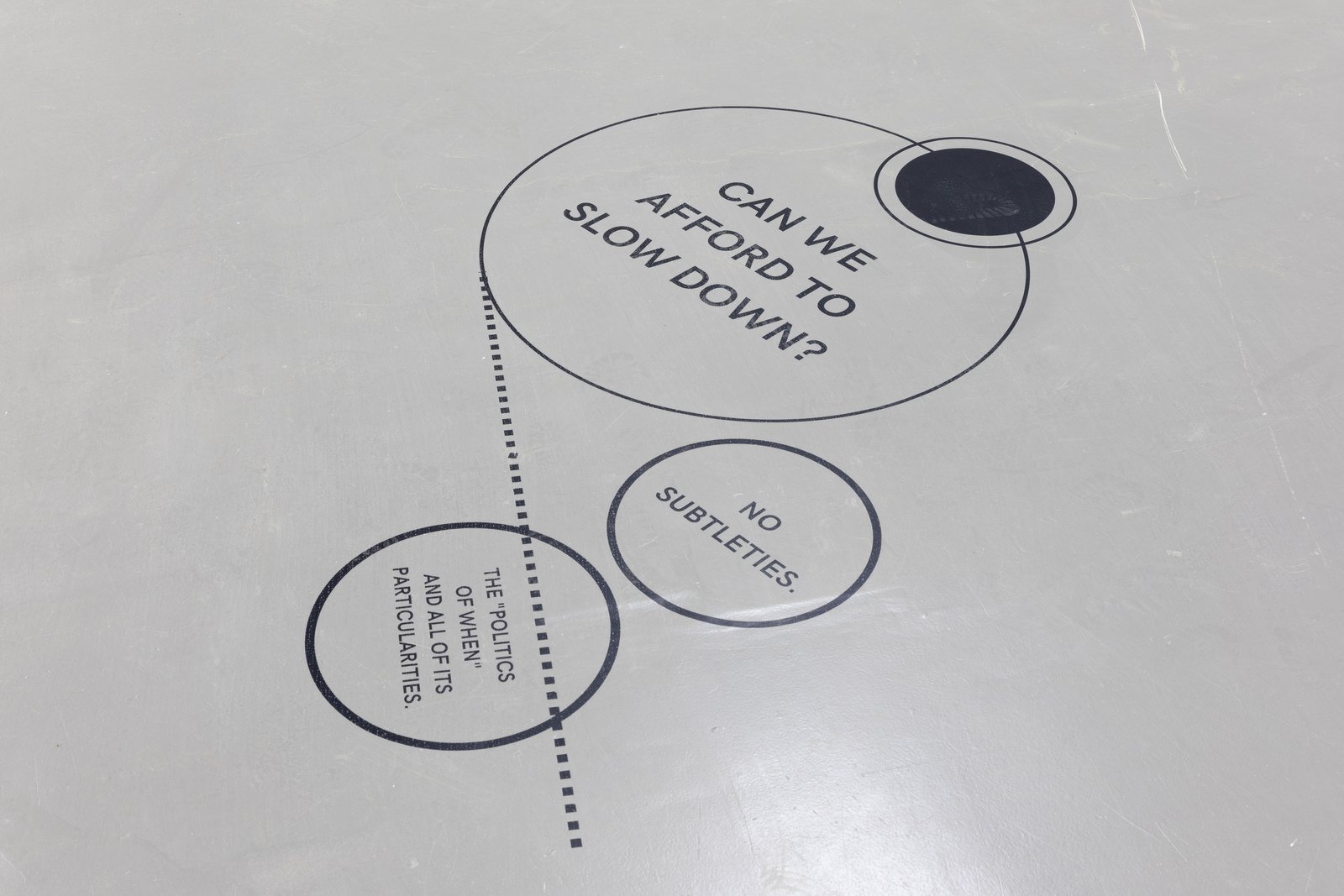

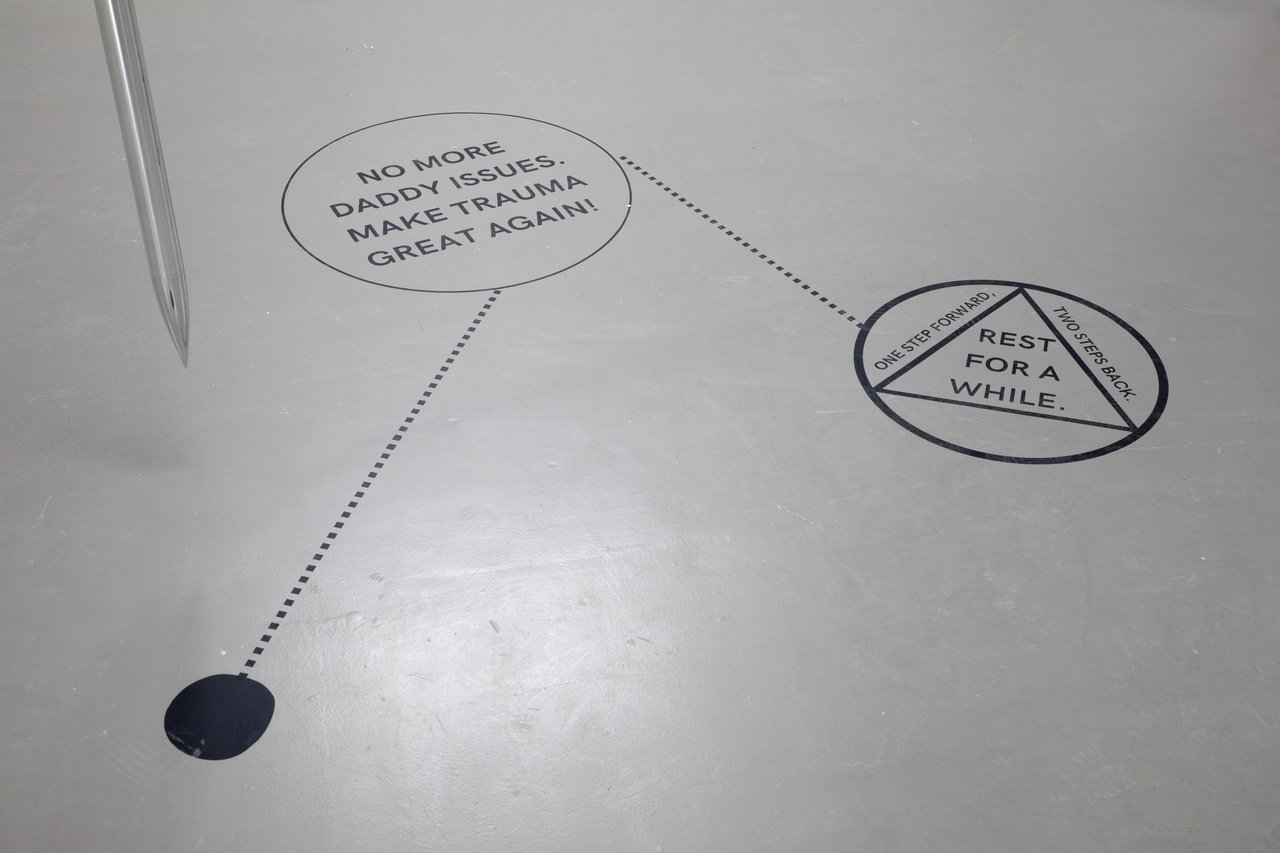

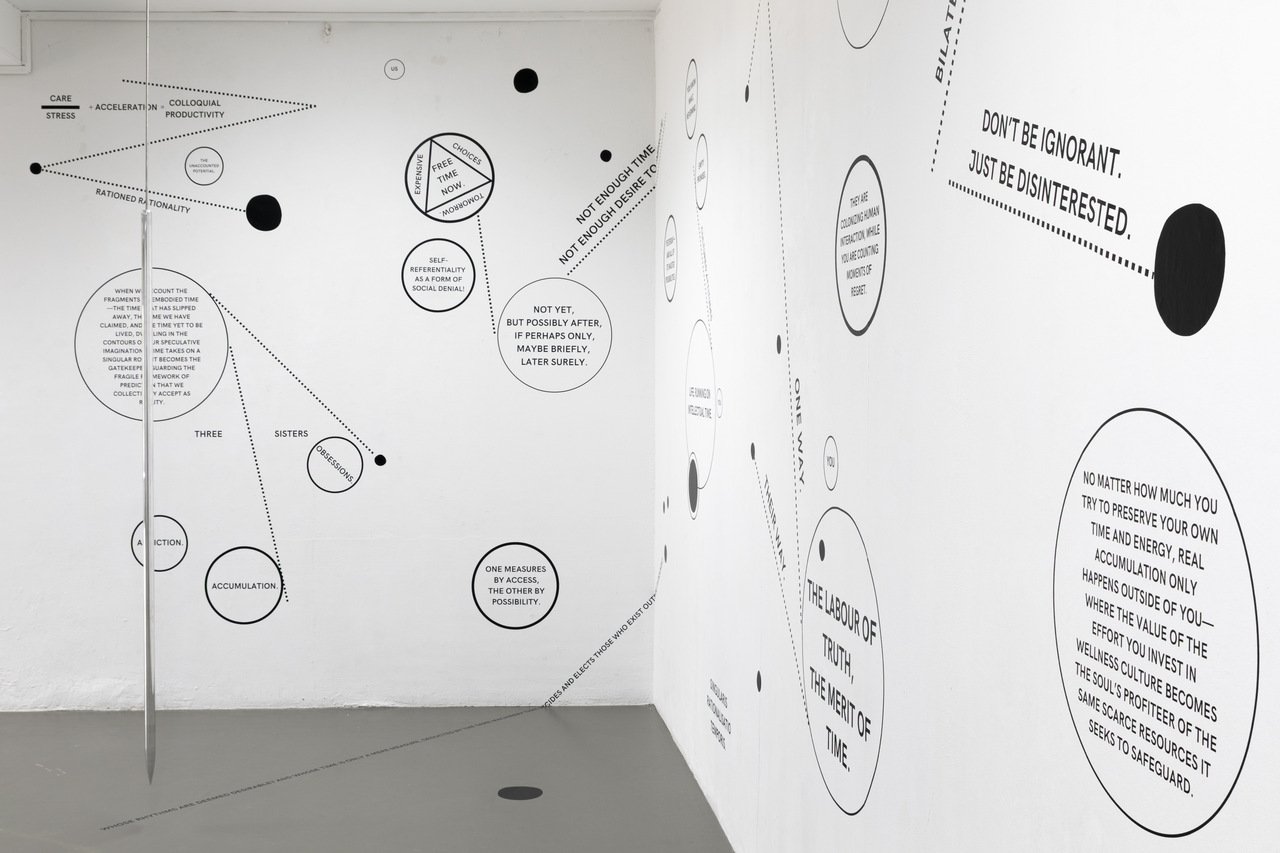

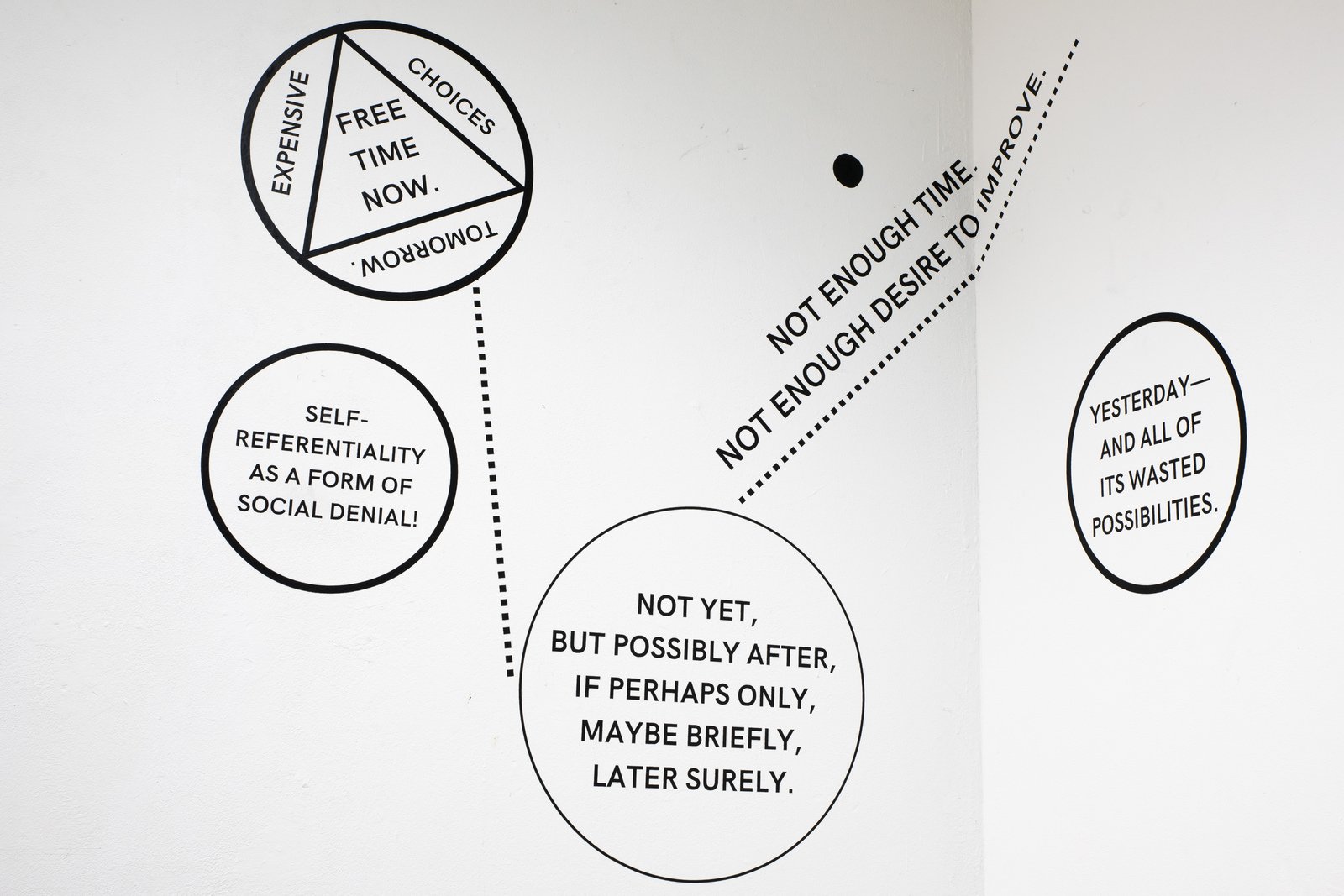

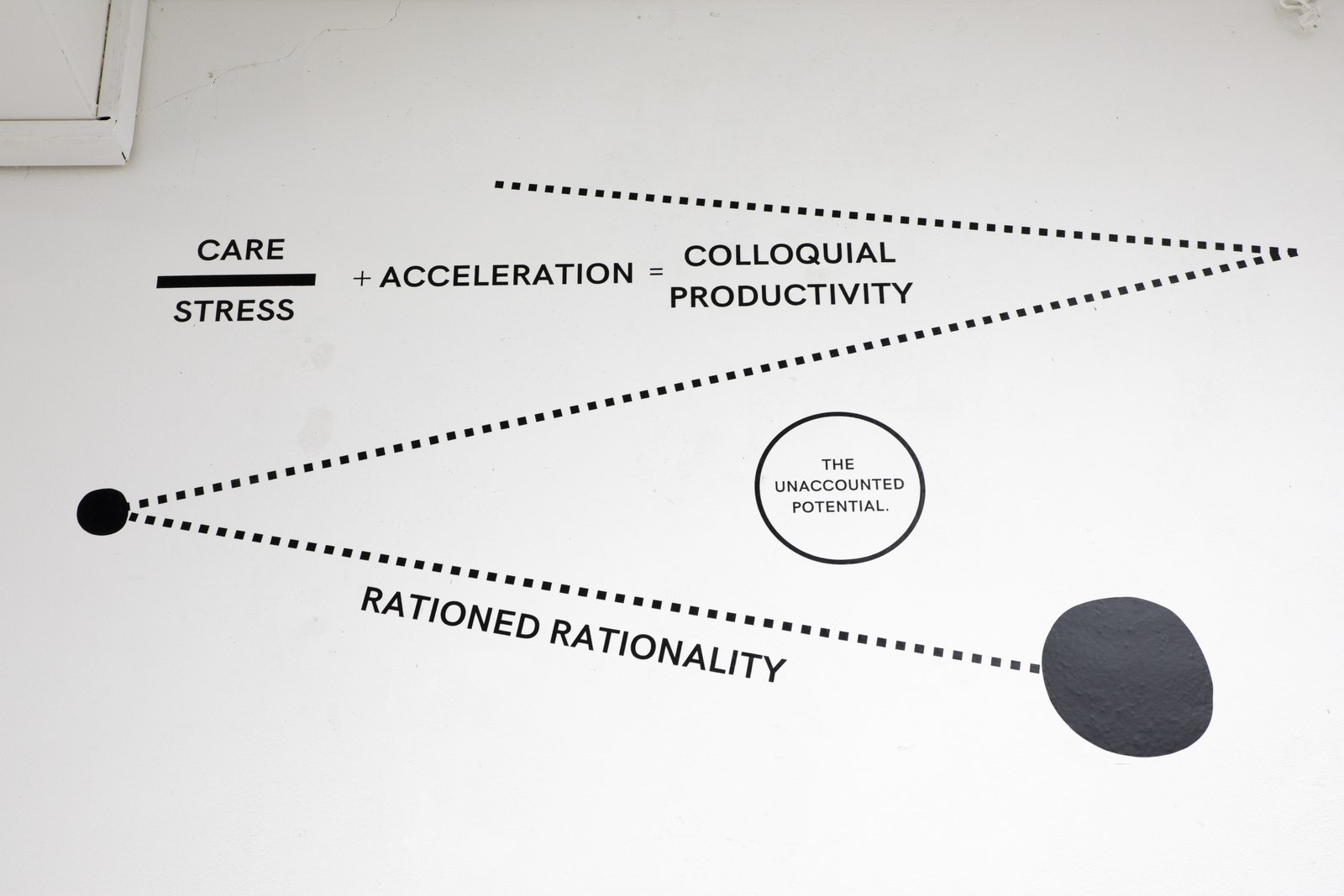

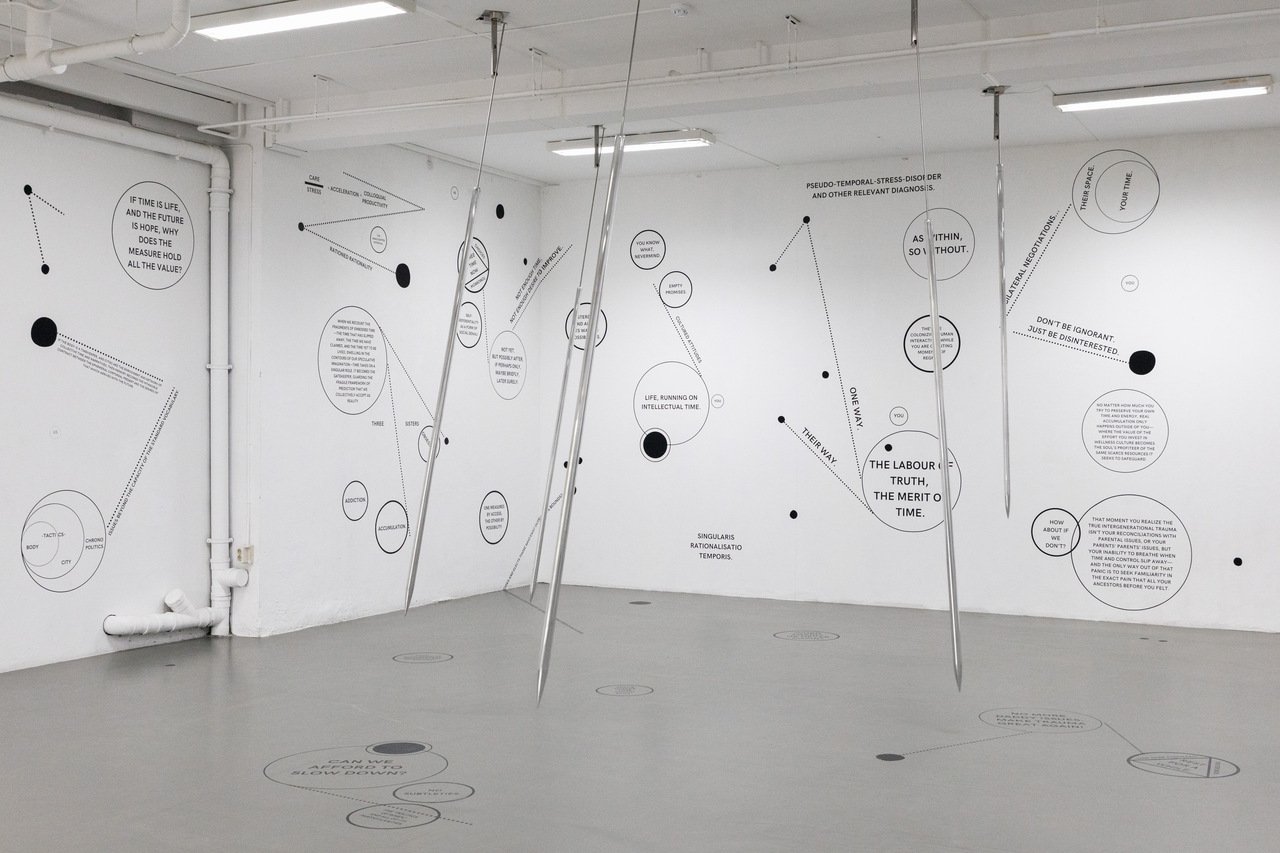

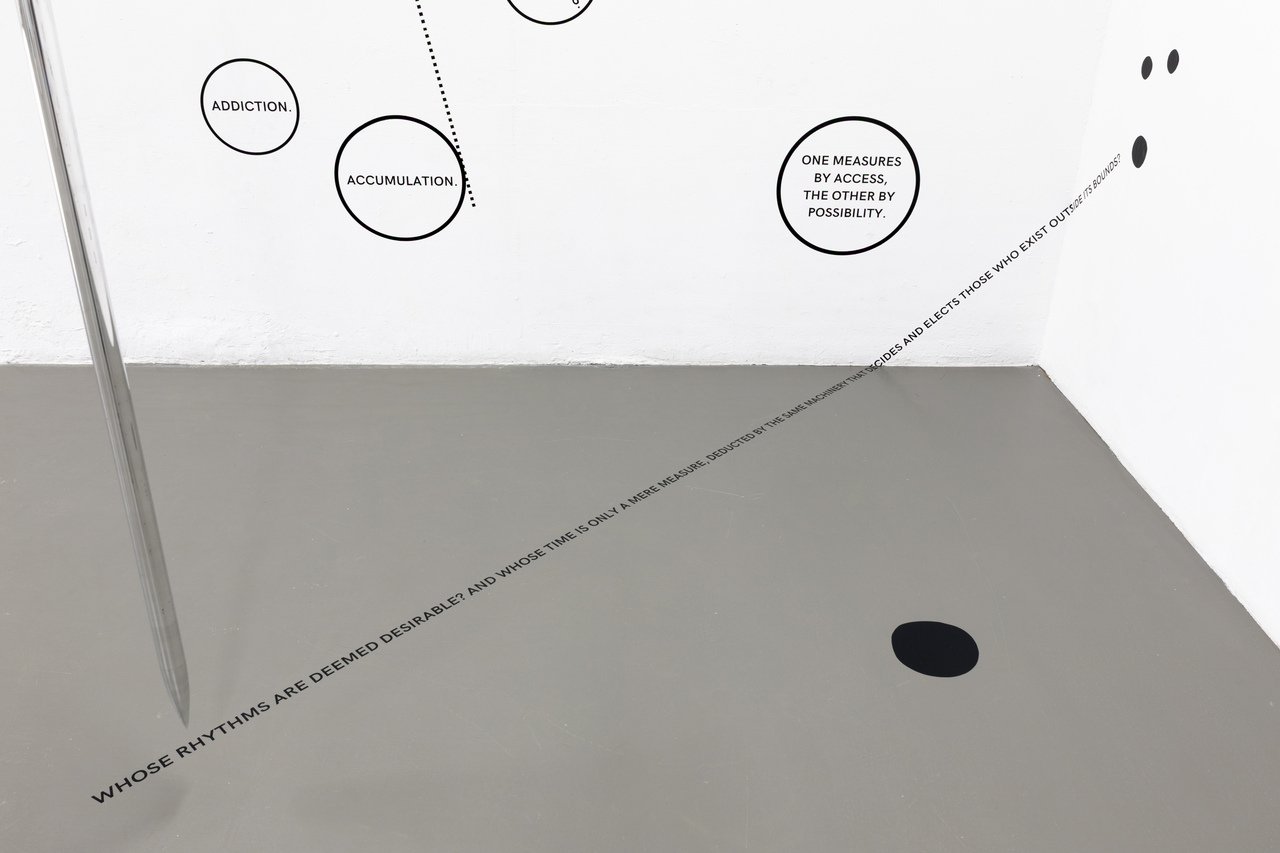

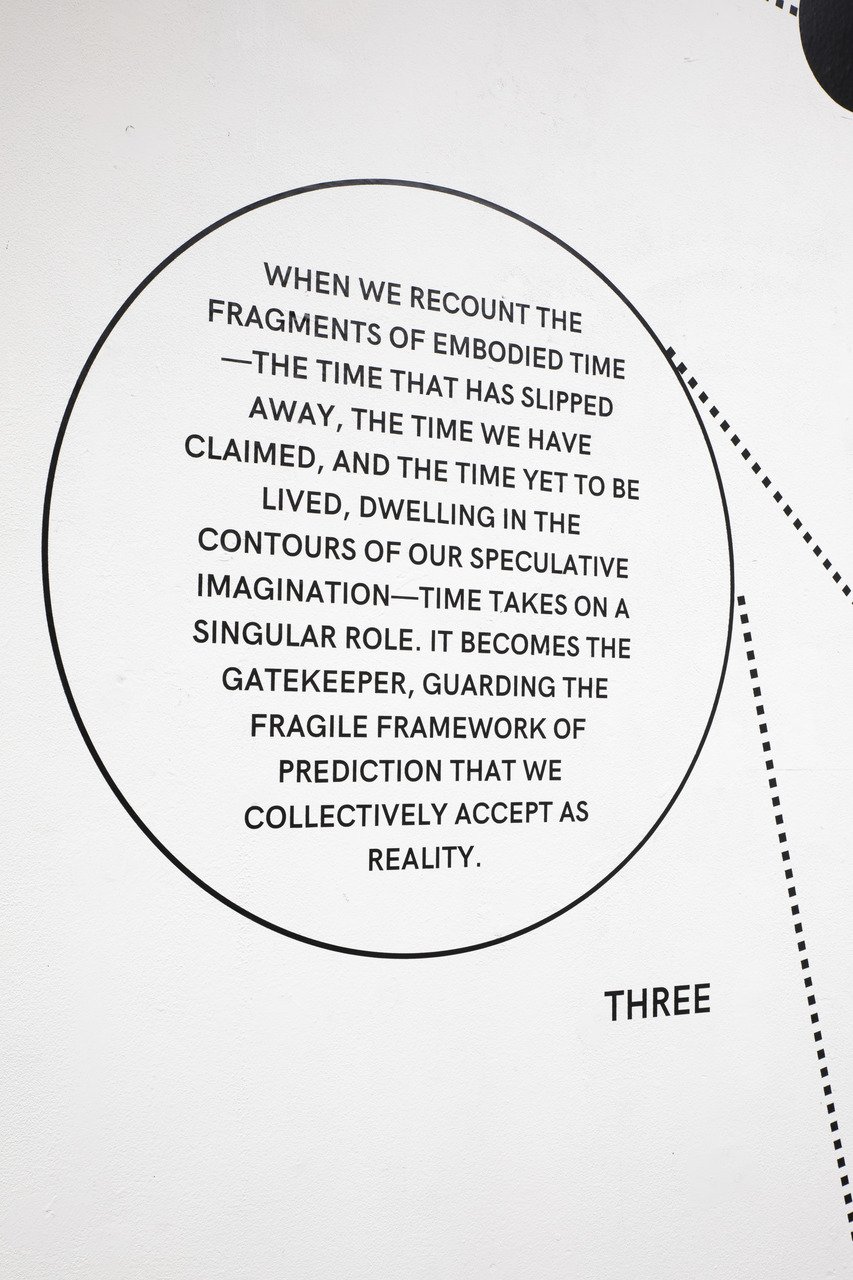

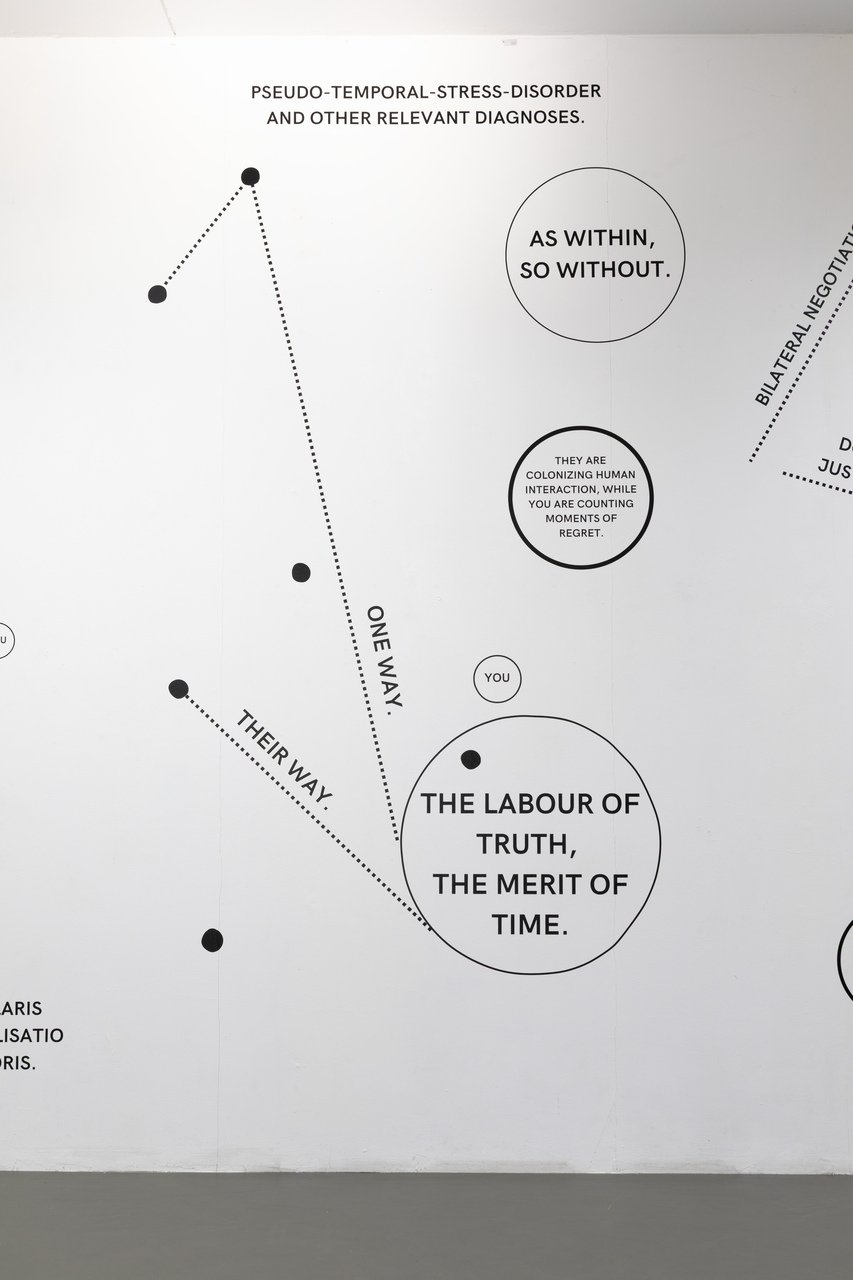

It is at this intersection of labour, power, and time that I encountered the works In Our Time and As Above, So Below (2025) by Andrea Knezović. A multimodal array of diagrams, instructions, kinetic installations, and textual scores that meditate on the tensions between bureaucratic, infrastructural, and personal time and labour. The pieces stem from a series of past spatial interventions that – through delay, repetition, and engagement – poke at these tensions, highlighting the ways productivity, endurance, and expectation are inscribed onto both body and mind.

At PAKT Foundation in Amsterdam, In Our Time and As Above, So Below (2025) was recently part of a duo presentation alongside Yeşim Akdeniz. The joint exhibition The Hard Edge of the Labour of Time, curated by Angels Miralda,deals with rest, or lack thereof.

Recently, I met with Andrea to discuss the themes of labour, bureaucracy, and fatigue unfolding throughout her installation in Amsterdam.

Lovre Mrduljaš: Andrea, your work often moves between audience instructions, diagrams, movement, and language. These elements engage timeas a lived, strained, and negotiated phenomenon. What are some broader concerns that currently motivate your work?

Andrea Knezović: It’s incredibly easy to fall under the expectations of capitalist time, especially when the time we reside in has been imagined, stretched, and borrowed as a bargaining chip in the service of what we understand today as a financial wheel of neoliberal speculation. My practice is currently driven by a sustained inquiry into chronopolitics – the politics of when – and how time operates simultaneously as infrastructure, resource, and mechanism of power. Drawing from thinkers such as Carlo Rovelli (The Order of Time), José Esteban Muñoz (Cruising Utopia), and T. J. Demos (Radical Futurisms), I examine how dominant temporal regimes shape not only labour and productivity, but also care, imagination, psycho-cultural environments and modes of existence. I am particularly interested in the dissonance between collective infrastructural time – accelerated, extractive, and optimised under techno-capitalism – and intimate, holistic temporalities that unfold through ritual, play, language, and embodied experience. Together, these perspectives allow me to question how dominant temporal regimes organise labour, care, and value. At the same time, my engagement with time is inseparable from my own position within late capitalist structures, where time is increasingly fragmented, borrowed, and pre-emptively exhausted. The expectation of constant availability, acceleration, and responsiveness has shaped not only my working conditions but also my perception of selfhood and sustainability. These pressures make evident how temporal norms are not neutral in socio-economic, cultural, and infrastructural sense but disciplinary – structuring who can rest, who must wait and/or be suspended in time, and whose futures remain deferred.

Instructions, diagrams, movement, kinetic installations and textual scores function as research tools through which this friction becomes visible in my art. These formats allow time to be staged as something negotiated rather than given, making visible its fractures and contradictions. Rather than offering prospective answers, my work constructs situations where temporal strain can be sensed, reflected upon, and potentially reconfigured.

LM: The Hard Edge of the Labour of Time at PAKT Foundation brings your work into dialogue with Yeşim Akdeniz, under Angels Miralda’s curatorial framework. What kind of coalescence, or productive resistance, do you see between your work and Yeşim’s?

AK: The encounter between Yeşim’s and my work in the exhibition unfolded through the convergence of very distinct material dialectics. While our practices engage with labour, mobility, and systemic constraint, they approach these concerns from different conceptual and embodied positions. I often investigate the mechanisms of cognitive capitalism and the co-opting of emotional and intellectual infrastructures embedded within institutional operations such as the economy, language, systems of behaviour, and cultural representation.

As a queer artist, my relationship to language and systems is deeply shaped by navigating multilateral ambiguities. Growing up as a queer female in Southeast Europe, I have often had to operate through unstable or indeterminate rules of language, bureaucracy, time, falling nations and institutional uncertainties. This has had a profound influence on how I work today and articulate performativity, humour, and satire in my works. Frequently, I use playfulness and a game-like mentality to expose tropes of failure, moments of transgression, and unrealised collective or individual potential. Play and multilateralism become strategies not only for material presentation but for survival within, and negotiation of, systems that are not designed to be fully legible or accessible.

My background plays a significant role in shaping this approach. I was born in former Yugoslavia, in what is now Croatia, and grew up during the transition of national and socio-economic orders from socialism to capitalism. I often say that Balkan cultures and societies exist in a constant state of transition, whether political, systemic, or socio-economic. Whatever the form or moment of that transition, there is an ongoing condition of alertness to change, or what some of us would call “in anticipation of uncertainty.” Within this context, language becomes a tool of recognition, reliance, and in some cases, even oppression (if not adequately adapted), and of course, a primary tool for navigating shifting paradigms. Language, in particular, became a strategic tool used to bridge between my internal modes of evolution and the external reality, shaping my adaptability, mentality, and horizons of imagination.

Looking at Yeşim, working from her position between Turkey and Belgium, and across roles as artist and educator, her practice is very much shaped similarly by the negotiation of multiple cultural, institutional, and political frameworks. In contrast, Yeşim’s work foregrounds embodiment and material intimacy, drawing from migratory experiences and cultural relationships through the tactile language of textiles. Where my work often traces internalised systems, Yeşim’s practice emphasises external infrastructures, objects, and spatial arrangements that shape access, visibility, and disclosure of control.

Placed in dialogue, the works reveal how power operates simultaneously from within and without, shaping subjectivity as much as material conditions. Within Miralda’s curatorial framework, this differentiality became generative. The exhibition functioned as a field of coexisting temporalities rather than a unified statement, reflecting my own experience of navigating institutional contexts that demand clarity while operating through fragmentation, delay, and contradiction.

LM: In one of the wall texts, you say: “If time is life and the future is hope, why does the measure hold the value?” Whether it is time, priorities, or production, the act of measuring is evidently important to this work. Could you expand on this gap between lived experience and systems designed to account for it?

AK: Indeed, measurement keeps appearing in my work because it carries a promise of objectivity that I find deeply misleading. When I ask, “If time is life and the future is hope, why does the measure hold the value?”, I’m questioning why numbers and metrics are often trusted more than lived experience. In Time and Social Theory (2013), sociologist Barbara Adam unveils the profound transformation of time into a currency of the capitalist world – a meticulous crafting of days, hours, and moments into measurable units traded in the labour market. This synthetic “machine-time” severs humanity from the organic rhythms of nature, replacing them with a relentless, all-encompassing standard that knows no boundaries of place or moment. This trap of optimised and controlled reality is embodied in the way we relate to value through our imagination and, consequently, language or naming. Our metric systems are limited by the boundaries of our imagination, and as it seems at the moment, our global imagination is focused on a vocabulary of quantifiable relationality. Perhaps in the future, our new social exercises and educational perspectives will be shaped by how we direct our thinking and govern our emotional landscape and its attachments, particularly in relation to language, rather than by the current embrace of a quantitative, competitive capitalist framework.

This gap between how time is lived through care, waiting, repetition, or uncertainty, and how it is administered by systems invested in the illusory attention to linearity and generative verticality constitutes one of the crucial sites of the despair of the imaginary in contemporary modernity. From personal experience, this gap becomes visible in moments that don’t fit neatly into cumulative metrics: burnout, anticipation, or prolonged waiting. These states are real and consequential, yet they rarely register as valuable.

My work doesn’t aim to reject measurement entirely, but to place it alongside lived time and expose its limits and its tropes. By doing so, I try to ask what kinds of lives become invisible when time is reduced to units, deadlines, and productivity targets.

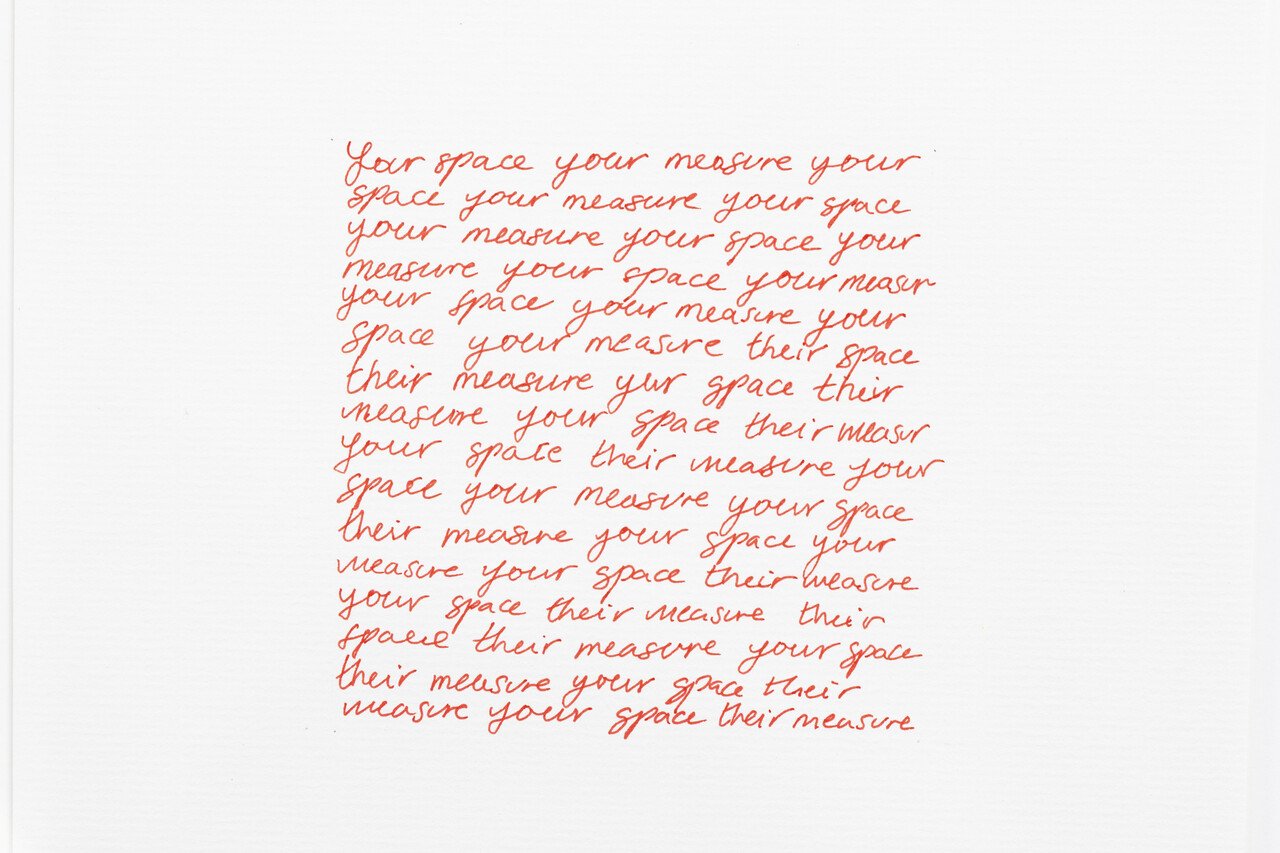

LM: Your drawing score, Your Space, Your Measure. Your Words, Your Rhythm (2025) blurs the line between what is ours versus what is theirs. It does so through laborious repetition of handwriting. Given this gesture, how does your work frame a term like fatigue?

AK: Most of my drawing scores grow out of an interest in inner psychic landscapes. They often sit in the space between emotion and cognition; between what is felt intuitively and what is structured, learned, or rehearsed. I work with wordplay, shapes, and compositional constraints to create drawings that function as riddles or performative scores, inviting the viewer into an active role. Although they exist as two-dimensional images, I think of them as relational spaces where reading, interpreting, and imagining become forms of participation.

I have long been drawn to psychology, interrelationality, and role-playing. One of the first books that left a strong impression on me in my youth was Eric Berne’s Games People Play, particularly his description of transactional analysis and the shifting inner roles of parent, adult, and child that we continuously move between in our interactions. This way of understanding social life as a series of exchanges and scripts still shapes how I think about my work. Rather than offering fixed meanings, my drawings invite viewers into situations where roles, expectations, and positions are subtly activated and negotiated.

Because of this, interaction in my drawing scores does not happen through touch, but through attention and relation. The works extend my ongoing attempt to create a connection between my own inner world and the spectator’s inner landscape. Abstraction and linguistic play become ways of meeting, tools for approaching vulnerability without fixing it in place. Repetition, riddles, ritualisation, and interpersonal systems return as recurring strategies for exploring psycho-cultural behaviour and the conditions under which we can relate to one another more openly.

In Your Space, Your Measure. Your Words, Your Rhythm, fatigue unfolds slowly through repetition. The repeated act of handwriting mirrors forms of quiet, ongoing labour that often remain unnoticed. Over time, the gesture shifts from expression toward endurance, allowing duration itself to come into focus. Fatigue, for me, is not simply exhaustion, but a way of understanding how time settles in the body.

As repetition continues, precision begins to slip, ownership becomes less clear, and the line between what feels personal and what feels imposed starts to blur. Personal space, the page, and language itself become shared terrains, sites of both relief and control. This reflects how temporal and emotional expectations are often internalised gently, through habits and norms rather than overt force.

At the same time, repetition opens small spaces of freedom. Slowing down, drifting, or allowing mistakes can become quiet acts of resistance. In this sense, fatigue holds both vulnerability and potential, resonating with José Esteban Muñoz’s idea of existing slightly out of sync with dominant rhythms, not outside of them, but gently misaligned.

LM: The language of your work carries a familiarity with systems of bureaucracy, in which delay and time hold a peculiar position. Where do you feel this temporal and bureaucratic sensibility comes from in your practice, if at all?

AK: The language in my work often plays with different registers of power, especially bureaucratic ones. This comes from lived experiences of institutional time – waiting rooms, delays, procedures, forms, emails left unanswered – all the small temporal frictions that quietly shape everyday life. Bureaucracy moves at its own pace, one that often feels disconnected from emotional or bodily time. Its language is typically impersonal, filled with jargon and abstractions that create distance rather than closeness, and that distance itself becomes a subtle exercise of authority.

I have always found this form of governance through language fascinating: how neutrality, complexity, or dryness are used to produce a sense of institutional superiority. I was raised with the idea that public institutions exist to serve people and their collective needs, yet so often the relationship is structured vertically, through procedures that enforce separation rather than care. Carlo Rovelli’s The Order of Time resonates strongly here, particularly his insistence that time is not a single, uniform entity, but something relational, experienced differently depending on position, context, and scale. Institutional time presents itself as universal and objective, while intimate time remains fragmented, uneven, and deeply situated in lived experience. This systemic distance, the feeling of being addressed without being truly seen, is something I return to frequently in my work.

Rather than mimicking bureaucracy, I am interested in understanding its psyche. I look at how macro systems cross-pollinate with micro experiences, how institutional rhythms seep into emotional life, shaping how we measure ourselves against expectations. This often produces a sense of being constantly “behind” or “not quite there,” a temporal condition that Anna Kornbluh describes as characteristic of late capitalism, where immediacy is promised but never fully delivered. By borrowing bureaucratic forms such as instructions, diagrams, or standardised language, I try to make these pressures visible. Introducing ambiguity, repetition, or slowness into these structures allows their human impact to surface, and opens space for alternative rhythms, ones that resist efficiency and allow time to unfold differently.

LM: Do you notice your work gravitating differently when read through various post-socialist labour conditions, migratory precarity, or the everyday negotiations of time under economic and political instability?

AK: Of course, context is always crucial for how I think and make work. Coming from an ex-Yugoslav context and living in Western Europe, I am constantly negotiating between different socio-cultural environments. The works I make, from metal kinetic installations to diagrams, drawings, and writing, carry these negotiations within them. They are shaped by moving between places with very different relationships to time, history, and productivity.

I think I was always interested in how different cultures deal with historical trauma and historical transgressions. Coming from a country that was disputed and then re-emerged as something else (nowadays Croatia), I became very aware of how remembering, forgetting, performing, and producing are entangled. Institutions, just like people, develop ways of managing the past, sometimes through commemoration, sometimes through silence, and often through productivity. Socialist and communist time functioned very differently from capitalist time, not only in how labour was organised, but in how time was measured, named, and collectively imagined. And please, don’t mistake me for nostalgic, I just recognise and am aware of these formats and differences: The excessive insistence today on speed, optimisation, and “hyper-” everything feels very specific to our moment, amplified by technological and political infrastructures that increasingly shape even our most intimate rhythms.

I often feel that my work tries to create gestures that are legible in both worlds. I am a child of transition, and that in-between position continues to shape my interests. I am drawn to liminality, to abstraction, and to situations where things are not fully resolved. Even though we are now deeply immersed in a techno-capitalist reality, I sense that many of us still carry memories of other temporalities – other forms of participation, other ways of measuring value and time. I am curious about the genealogy of that memory, and about how long it will remain accessible. When my work is read through post-socialist or migratory contexts, where time often feels unstable or provisional, these questions become especially visible. Rather than offering universal answers, I try to stay with these specific conditions and ask what they can teach us before they are forgotten.

LM: As As Above, So Below (2025) and In Our Time (2025) travel between Amsterdam and Istanbul, the works inevitably enter another temporal and geopolitical context – one that sits at the intersection of Europe, the Balkans, and the Middle East. How do you anticipate this shift affecting the kinds of new readings or frictions that might emerge when the installation is experienced within this new context?

AK: Istanbul embodies what Walter Benjamin described as “history as a constellation,” where past and present collide rather than follow a linear trajectory. Byzantine churches coexist with Ottoman mosques, colonial-era palaces sit beside modernist towers, and marketplaces continue patterns established centuries ago. In contrast, Amsterdam reflects a more legible temporality, shaped by Enlightenment ideals of planning, order, and civic progress. This shift foregrounds the work’s interest in reflecting verticality – the above and below, visibility and erasure, power and neglect – within a geopolitical context where history is continuously negotiated, rather than settled, by the accumulation of empire, trade, and migration.

The connection to the Balkans, and my own origins, adds another layer of temporal and geopolitical resonance. The Balkans have long been a liminal space, historically caught between empires, ideologies, and borders. Concepts of “contested memory” explored by scholars such as Maria Todorova illuminate how these regions experience history as negotiation, struggle, and layered identity, rather than linear continuity. Amsterdam, by contrast, represents a European ideal of rationalised historical narrative and urban order, at least appearing from the surface. By placing the work across these geographies, the installation becomes a site of dialogue between different temporal logics: the accumulation of memory, the politics of visibility, and the ways that geopolitical shifts, such as Ottoman withdrawal, European colonial ambitions, and contemporary migration flows, shape both cultural perception, social attitudes, and hierarchies.

Collaborating with Yeşim, situated within her native context, brings a lived and diasporic perspective to these ideas. Her work interrogates how political and cultural displacement shape temporality, memory, and embodied experience, often referencing migration and the circulation of cultural memory between Turkey and Europe. In contrast, my work emphasises the political dimension of time: whose histories are preserved, whose are forgotten, how we relate to and measure these parameters, and how such choices reproduce or challenge existing power structures. Istanbul amplifies these questions: a city where centuries of geopolitical exchange, imperial control, and cultural negotiation are inscribed in both architecture and everyday life. Here, audiences encounter time not as abstract or linear but as layered, accumulative, and contested.

Curated by Miralda, the exhibition becomes an orchestration of these tensions. Angels’ curatorial practice always tries to test boundaries of the given formal context, foregrounding how spatial and temporal politics shape perception. In this context, my work in Istanbul operates as a threshold rather than a statement, a site where historical sediment, political time, and cultural memory intersect without resolving into certainty. Together, the works address the audience through rhythm, repetition, and calibrated movement, evoking a metronomic sense of time that is both intimate and imposed. If all time is local, then what is revealed here is not its passage, but the politics embedded in how we learn to inhabit it.

Andrea Knezović is a visual artist, researcher, and writer based in Amsterdam. She holds a Research Master’s degree in Artistic Research and Critical Theory from the University of Amsterdam and a Bachelor of Honours in Visual Arts from the Academy of Visual Arts (AVA), Ljubljana. Her practice moves between artistic inquiry, critical theory, and institutional tactics, mapping the entanglement of intimate and institutional systems through subversive gestures and dialectical methods that explore identity politics, care, and structural power. Working with language, speculative infrastructures, and game-like rituals, she examines how bodies and subjects navigate liminal spaces shaped by chronopolitics, cognitive capitalism, and socio-political ecologies, proposing new forms of resilience and knowledge production.

Knezović is a co-author of Nocturnalities: Bargaining Beyond Rest (Onomatopee, 2025). Her writing has been published by MIT Press (Thresholds), Set Margins (Eindhoven), and Simulacrum (University of Amsterdam). She was a BAK Fellow for Situated Practice (2023/24). Her work has been exhibited internationally at institutions and events, including P/////AKT Amsterdam (2025), U3 Triennale (2024), Panorama Venezia (2025), MUZA Museum (2025), BAK, basis voor actuele kunst (2024), MSUM Ljubljana (2024), Cukrarna (2023), Keller Gallery at MIT (2022), Kiribati National Museum (2019), among others. Her work is held in numerous institutional, corporate, and private collections, including the Museum of Contemporary Art Ljubljana (MG+MSUM), MSU Zagreb, SCCA–DIVA Archive, and the NLB MUZA Art Collection. Alongside her artistic practice, Knezović is active as an educator, board member, and advisor within several art-related institutions. Andrea lives and works between Amsterdam, Ljubljana, and Zagreb.

Lovre Mrduljaš is a curator based in the Netherlands. He obtained a degree in Art History from the University of Groningen and began his curatorial involvement at SIGN Projectspace in Groningen in 2024. In 2025, he worked as a guest curator at Media Art Friesland in Leeuwarden and as a curatorial assistant at the National Museum of Modern Art in Zagreb, where he contributed to the exhibition WORK – Creation and Realization (2025). His writing includes the interview Who Is Nelly Dansen? (2024) for SIGN Projectspace and a profile of Jens Buis’s Sync I & II (2025) for Media Art Friesland. He currently lives and works between Amsterdam and Split.

[1] Bataille, The Accursed Share, 1949, 29

[2] Pepi, Asynchronous! On the Sublime Administration of the Everyday, 2016, e-flux

Artists: Andrea Knezović & Yeşim Akdeniz

Exhibition Title: The Hard Edge of the Labour of Time

Curated by: Àngels Miralda

Venue: PAKT Foundation

Place (Country/Location): Amsterdam, Netherlands

Dates: 1 November – 7 December 2025

Photos: All images courtesy of the artists. Photography by Bart Lunenburg.