Oleksandra Pogrebnyak

We wake up and spend a few minutes talking, tickling each other, doing a kind of pretend morning exercise – more like lying down or rolling on the rug by the bed. We go down to the record player and pick out a vinyl. Then Teo dances or rides his little car while I check the fridge, looking for a snack to offer him before he has his breakfast in preschool. By 9:30, once I’ve dropped him off, I’m alone. In that moment – if I can’t reach Dmytro or don’t have to rush to a meeting – silence folds around me.

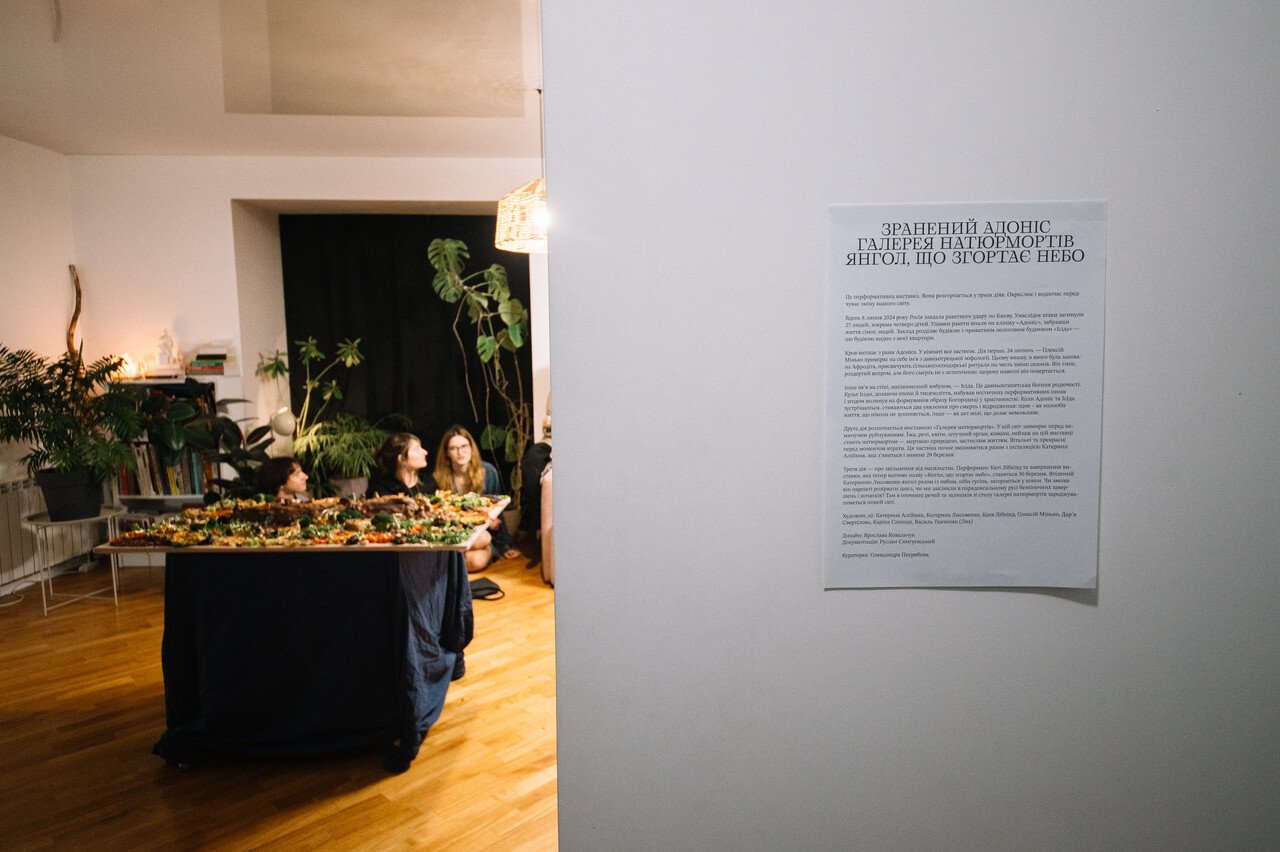

With this text, I am eager to share the story of my latest apartment exhibition, in conjunction with some aspects of domestic and wartime life in Kyiv in recent months. It began in February, with the performance Wounded Adonis by Olexii Minko. In March, the other two performances by Kateryna Aliinyk and Katya Libkind took place alongside the exhibition which also included photography, paintings, and video. With attention to the character of a happening, it appeared under two changing titles: Gallery of Still Lifes and Angel Folding the Sky.

The exhibition took shape over three chapters, in a period when our family life changed significantly. And so this year’s conceptual framework was also about change – about the disappearance of a world we loved, and about discovering new joys and creating a sense of stability amid constant uncertainty.

This was the third year I celebrated my birthday by opening an exhibition at home. Once you know it falls on February 24, the story naturally gains a dramatic tone. In 2022, my husband, Dmytro Chepurnyi, and I experienced the start of the full-scale invasion right here in this apartment. A year later, in 2023, still in Kyiv, through the metaphor of thickets, I reflected on themes of rootedness: why didn’t we leave our home when it was under unprecedented threat? The answer was found among the artworks: to care for potted flowers, for our neighbours, for situational communities.

Our family, in a way, has never existed in a peaceful time: we married in early March 2022, while Kyiv was still under the threat of siege, and the next winter we discovered we were expecting a baby. The following year and a half were devoted to milk and motherhood and were reflected in my next birthday exhibition, Milk for Teo. Through the recent experience of giving birth, I tried to define what a safe space now means to me, and how my relationship with my child helps me to imagine a future again.

By winter 2025, the exhaustion was palpable. Our lives gained particular intensity, as if every moment demanded to be lived fully. The exhibitions and artworks, too, carried their own urgency – each gesture had to take place in the present. Oliver Basciano, a journalist who came to write about the PinchukArtCentre Prize 2025 exhibition, which I curated, started his article by saying that everyone he met in Kyiv seemed incredibly tired. While his words resonate, I would like to offer another perspective: the idea of exhaustion as a source of becoming. Yes, we rarely sleep well. Every month, thousands of Shahed drones and dozens of ballistic missiles fly over the country. Their time is night – a russian play of terror. When going to bed, you hope to fall asleep before the air raid alert sounds, just to get at least some rest.

The idea of living in peace remains hard to let go of. Once, when our vision of happiness, peace, and abundance was shaped by an artificial stillness – stripped of the complexity and tension that real life carries – we convinced ourselves that it was the only way to live. Long after February 2022, we held on to vivid images of peace, speaking of “after victory” or “after war.” But with the passage of years now in full-scale war, a new realization emerges: life may unfold in ways we never imagined. The adulthood and the lives we once looked toward are already here – in our homes, our gardens, our children, even as we continue to fight this brutal war.

In this, joy matters. It no longer comes easily; it appears in defiance of the moment and is an insistence on being alive, on caring. Joy doesn’t deny the sorrow for those we have lost and the mourning of the peaceful lives we once knew, but appears beside it, offering brief clarity and connection. In curatorial work and daily tenderness, we protect these moments – not as escape, but a way of holding the world together when it threatens to fall apart.

This text is a reflection on the slow and sometimes painful act of acceptance that we are changing irreversibly. The exhibition itself is a marker of this.

In 2022, I couldn’t have imagined my husband becoming a soldier – even when the Ukrainian army was rapidly increasing in numbers to fight back against russian invaders. At the time, we were directing our cultural energies outward, joining the chorus of voices speaking on behalf of a country under attack. But when the fighting didn’t stop – not after six months, not in 2023, not in 2024 – by early 2025, I began to feel how fragile our world had become. Still deeply rooted in the artistic context, yes – but now held together mainly by our shared care for our son, Teo.

The performance Wounded Adonis took place on February 24 as the first act of the exhibition – a birthday greeting from artist and performer, Olexii Minko. He embodied the mythological character of a young man whose death and rebirth are celebrated by seasonal rituals. Bleeding from a fatal wound, plants begin to grow from each drop of blood. Perhaps the same plants that were meant to become, in Adonis’s words, “Teo’s garden in Zhanna’s yard.” While preparing for the performance, Oleksiy asked what gift I might wish for. A strange question, when in both 2023 and 2024 the best gift was simply that the worst predictions never came true: no nuclear strike, no new assault on Kyiv, despite all the forecasts. I answered: I want the chance to retreat. Like growing a garden with my son in the courtyard of artist, friend, and neighbor, Zhanna Kadyrova.

The garden often becomes a metaphor for artistic projects. A utopia that arranges everything around the figure of the gardener, where care and love are sure to bear fruit. Yet gardens change with the seasons. To imagine abundance without decay, my mind drifts instead toward still life – or rather, a whole gallery of them. Painted compositions of freshly cut flowers, ripe fruit, translucent crystal, and silver dishes as evidence of inexhaustible grace. A genre that, at first glance, glorifies the overflowing richness of life. But a still life always carries a subtext of impermanence and fragility. Bitten fruit loses its juice, flowers their scent and beauty, hunted creatures become empty skins. I’m drawn to that moment of peak bloom and lushness. A moment of carefree joy that captures something already gone, already rotten, decomposed, turned to carbon. Our joy, too, always comes with a hint of change.

In March, my husband became a soldier. Teo and I were on our own and had to reinvent our daily life and our relationship. For Teodor, his father means a lot, and I had to make sense of what connects us in the absence of Dmytro. What our bond is made of now, after the transition from milk. I had to create a new experience for us.

Three days after Dmytro left was the scheduled date for the performance and the exhibition titled Gallery of Still Lifes – it was just the two of us, me and Teo, with the help of friends and artists, preparing for the event. This was the second act of my three-part exhibition, and it included recently created paintings of a broken tree branch on a street in Kharkiv by Karina Synytsia, photographs by Daria Svertilova from the last nature reserve on the Black Sea coast still under Ukrainian control, and drawings of everyday objects from Vasyl Tkachenko (Lyakh). The evening featured a performative still life by Kateryna Aliinyk, transforming the traditional genre into a collective happening. The World is so Abundant, it Rots was a piece composed of a log, insects, soil, and grass – all made of food. An edible image of the Luhansk region, which Kateryna has been reimagining over the past three years through her paintings and drawings.

Before the curatorial speech, people gathered around Aliinyk’s table with a specific tenderness, hesitant to disturb the delicate harmony of the arrangement. Everyone was welcomed to enjoy it. As they did, the experience shifted: the first cautious bite gave way to a shared delight of the flavors the artist had carefully chosen. Brown rice, greens, pancakes, mushrooms, dried fruits and nuts – I know it was important to Kateryna that her still life was particularly delicious. She made sure of it. Sweet, tangy, earthy, sometimes unknown and sometimes familiar – she wanted the tastes she associates with home to be shared by everyone present.

In the same room was Kateryna Lysovenko’s watercolor triptych, Angel Folding the Sky, a reimagining of motifs from her earlier fresco, less dramatic and instead infused with a glimmer of hope within the swirling forms of the apocalyptic biblical narrative. It towered over the table, gazing at the gallery and at the relaxed friends with full bellies resting nearby. The next day’s performance by Katya Libkind concluded this year’s exhibition. Referencing the canonical story of the end of the world, it shared its title with Lysovenko’s watercolor.

From myth and pagan cults with sacrificial rites to the Christian narrative of blood and salvation, the archetypes of blood and death, of destruction turning into renewal, recur again and again. Being inscribed in the body of culture itself – and repeating until they arrive at another kind of liturgy – the space of contemporary art. Today, this feels painfully immediate: blood appears as an image, metaphor, or material for an artwork. In a country at war, donating blood has become an urgent, protracted routine. When blood leaves the body – through a cut finger, a nosebleed, menstruation, or even Adonis’s fatal wound – it feels almost natural. But when blood returns through a drip, it carries the weight of sickness or injury, of damage from an attack. At the same time, it also suggests a certain rebirth: each fight for life makes its meaning shift, demanding reconsideration.

During her performance, Libkind casually sat in the bathroom and collected her blood into a medical bag. Simultaneously, the bath filled with bubbly water as the washing machine cycled with pocket-sized paintings of skies inside. Briefly leaving the body, the blood was then returned to the organism through another catheter. A potentially endless act looped in on itself, symbolically breaking the still-life spell, pulling us back into the reality of blood – the measure of life and loss in Ukraine today.

In Katya’s film Dream During Curfew, also a part of the exhibition, the presence of blood quietly anticipates the performance. A sculpture made of frozen blood forms an artificial organ, a penis without a body. During the film, it slowly melts, accompanied by a tender breath – perhaps human, perhaps a mythical forest spirit, or a dreamlike phantom embodied by the author. At last, the sculpture collapses into still life: a textured beige wall, a clay pan, a pound of blood.

As the skies folded in the cycle of the looping machine, and as blood existed independently of the body, I was brought back to the dawn of February 24, 2022. To my birthday – the day the full-scale war began – and to the instinctive urge that grew into my annual apartment exhibitions. To the origin of my personal existential terror. To Adonis, not only the lyrical figure in the performance by Olexii Minko, but also the name of the hospital struck by a russian missile in the summer of 2024. To the dust cloud from the explosion that was clearly visible from our window. Reconstruction of the destroyed floors is still ongoing – guests could see it happening on their way to the exhibition, crossing the bridge near our home. Perhaps another performance, unfolding in parallel.

In Kateryna Lysovenko’s watercolour, the angel is not distant or detached, but folds into a cocoon where the first ray of new life is already visible.

What I feel now is a strange kind of joy that comes simply from having made it through, for now. It exceeds a profound acceptance of possible loss – even of your own life or a life as you have known it: familiar rhythms, imagined futures, a course of continuity.

***

On March 27, 2025, my husband Dmytro enlisted in the Armed Forces of Ukraine and is currently serving as an active-duty soldier. Not long after, I received this letter, which I read as him stepping into his “new dreams.”[1]

Our experiences continue to diverge, but conversations about curatorial practice and our son remain a shared space of understanding – a fragile thread that still connects our two worlds. In this new reality, I see these apartment exhibitions as a feminist form of reclaiming private space – not as a withdrawal, but as a site where care, reflection, and artistic thought can coexist, offering an individualized form of resistance, and a way to stay present amidst ongoing rupture.

[1] Alongside a reference to Libkind’s practice, here I recall the first chapter of Artem Chekh’s Absolute Zero, which reflects on his experience in the war from 2015–2016.

Artist: Kateryna Aliinyk, Katya Libkind, Kateryna Lysovenko, Olexii Minko, Karina Synytsia, Daria Svertilova, Vasyl Tkachenko (Lyakh)

Curated by: Oleksandra Pogrebnyak

Exhibition Title: Wounded Adonis / Gallery of Still Lifes / Angel Folding the Sky

Venue: Transit Culture – a curatorial space in the apartment of Oleksandra Pogrebnyak and Dmytro Chepurnyi on the Left Bank of the Dnipro in Kyiv

Place (Country/Location): Kyiv, Ukraine

Dates: 24.02.2025, 29.03.2025, 30.03.2025

Photos by: Ruslan Synhaiewsky

Design by: Yaroslava Kovalchuk