Zofia nierodzińska

The last time I was in Poznań, for the opening of an exhibition I co-organised at Galeria Łęctwo, I happened to rent a room overlooking two newly restored Jewish graves.[1] The reconstructed tomb of Rabbi Akiva Eger turned out to be one of them. Downstairs, by the entrance gate, there was a plaque commemorating the site and stating that where the halls of the Poznań International Fair now stand, there was a Jewish cemetery destroyed during the Second World War. The matzevot from the graves were used to pave Głogowska Street, which I walked every day to the gallery, as well as line the bottom of the artificial lake Rusałka (formerlyElsensee). The Freedom Highway connecting the border crossing at Świecko with Poznań, to which Głogowska Street leads and which I had driven the day before, was built by enslaved Jewish workers from the Wielkopolska region who were forcibly held in labour camps, the largest of which was at the Edmund Szyc Stadium. Today, few people are aware of this fact. The only reminder of the camp is a small and easily overlooked monument on Św. Jadwiga Street. A few years after the war, the stadium returned to its original function, hosting football matches and mass events as if nothing had happened. Only now, eighty years after the war, is it to be turned into a park with a memorial site.

In their opening text of the bilingual Polish-German catalogue for Illusions of Omnipotence:

Architecture and Everyday Life under German Occupation at CK Zamek, Aleksandra Paradowska (curator) and Annika Wienert (curatorial collaboration) write about the “troublesome legacy” of architecture in Poznań, which records the history of wartime violence, the plans for Germanisation, and the personal stories of the people who were forced to work on their implementation. Many of whom, having been used as labour, were eventually killed. The lives of the Polish population, especially the enslaved and later murdered Jewish minority, lie beneath many of the Third Reich’s “infrastructure projects” in Poznań that are still in use today, such as the aforementioned Rusałka Lake, which was built using forced labour. It was only in 2020, thanks to the efforts of local activists, in particular Maciej Krajewski of Stowarzyszenie Łazęga Poznańska, that a modest plaque was erected in the cities most popular recreational spot to commemorate the history of the place and the lives that had been lost during its construction.

It is no coincidence that this exhibition on architecture and German expansion plans for the East was organised in the building of the former Imperial Castle, built between 1905 and 1910, when the western part of Poland, including Poznań, was under Prussian annexation. During the Second World War, the residence of the last German Emperor Wilhelm II was redesigned and converted for administrative purposes under the direction of Arthur Karl Greiser, the Gauleiter (regional leader) and Reichsstatthalter (Reich Governor) of the Warthegau. The castle itself and the whole occupied region was to be a showpiece of German superiority in the newly conquered eastern territories, a symbol of dominance, including the aesthetic kind, which involved Entschandelung, or “bringing order to chaotic Polish architecture.” This term was a very specific key word used by the Nazis to denote the redesign and reconstruction of buildings to enforce the ideology of the oppressors. The landscape was also appropriated for the totalitarian vision of the occupiers; everything associated with Polishness and Jewishness had to be destroyed to make way for the new aesthetic of the Nazi regime. What was disappeared from the picturesque villages and propaganda landscapes were the murders of thousands of forced labourers, the deportations, and executions that took place in the forests and camps, such as the infamous Kulmhof (Chełmno nad Nerem). Artists associated with the Third Reich presented an idealised, even idyllic, vision of the world. In this way, the conquered population was “removed” from the landscape, both symbolically and in the most material sense. The landscape became a tool for propaganda, a smokescreen that concealed the atrocities committed by the occupiers.

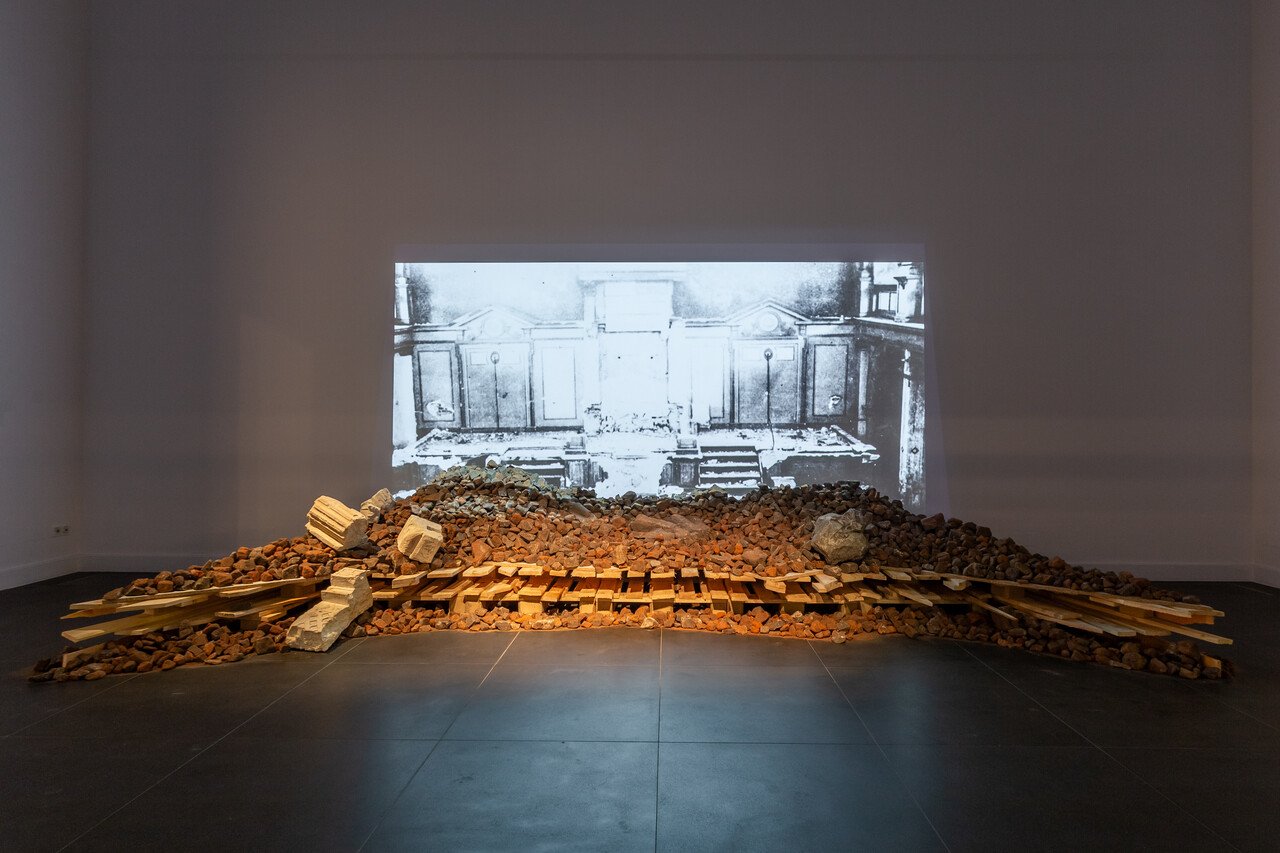

Set in the historic castle and divided into three parts, the exhibition occupies the rooms that had been converted for Hitler’s residence – Hitler himself never made it to Poznań because the front advanced unexpectedly fast and before Greiser could show off his reconstruction, the city was recaptured by the Red Army. The first part, located in the biggest space, deals with the plans to displace the local population and replace them with German colonists. They planned to build settlements for Germans only, with houses with sloping roofs, to transform streets into avenues representing domination, and, most devastating of all, to create ghettos[2] for the Jewish population, whose spatial segregation was the first step towards the Holocaust. This first room also shows what this Entschandelung looked like in practice, using the actual rubble of the destroyed synagogue in Rawicz which was slated to be converted into a cinema but instead, it was destroyed.

In this context, the troubled history of the New Synagogue in the very center of Poznań is also worth mentioning. Built in 1906 by the Berlin architectural studio of Cremer & Wolffenstein, the magnificent neo-Romanesque building was converted into a swimming pool during the occupation and remained in use as such long after the war, until 2011. I remember when I was a student at the Academy of Fine Arts (now the University of the Arts), I had the choice between swimming lessons in the synagogue or gymnastics in a conventional gym: I chose the latter. After the war, the synagogue was managed under the authority of the municipality, who saw no problem with maintaining its recreational function after its German occupiers. In 2002, it was returned to the Jewish Community of Poznań, which, due to a lack of funds and support from the city, decided to sell the building in 2019 to Campione Investment. The company plans to turn it into a block of flats, contrary to the community’s original idea of creating a Centre for Dialogue and Judaism. The current situation is that one of the largest synagogues in Poland is in a state of decay.

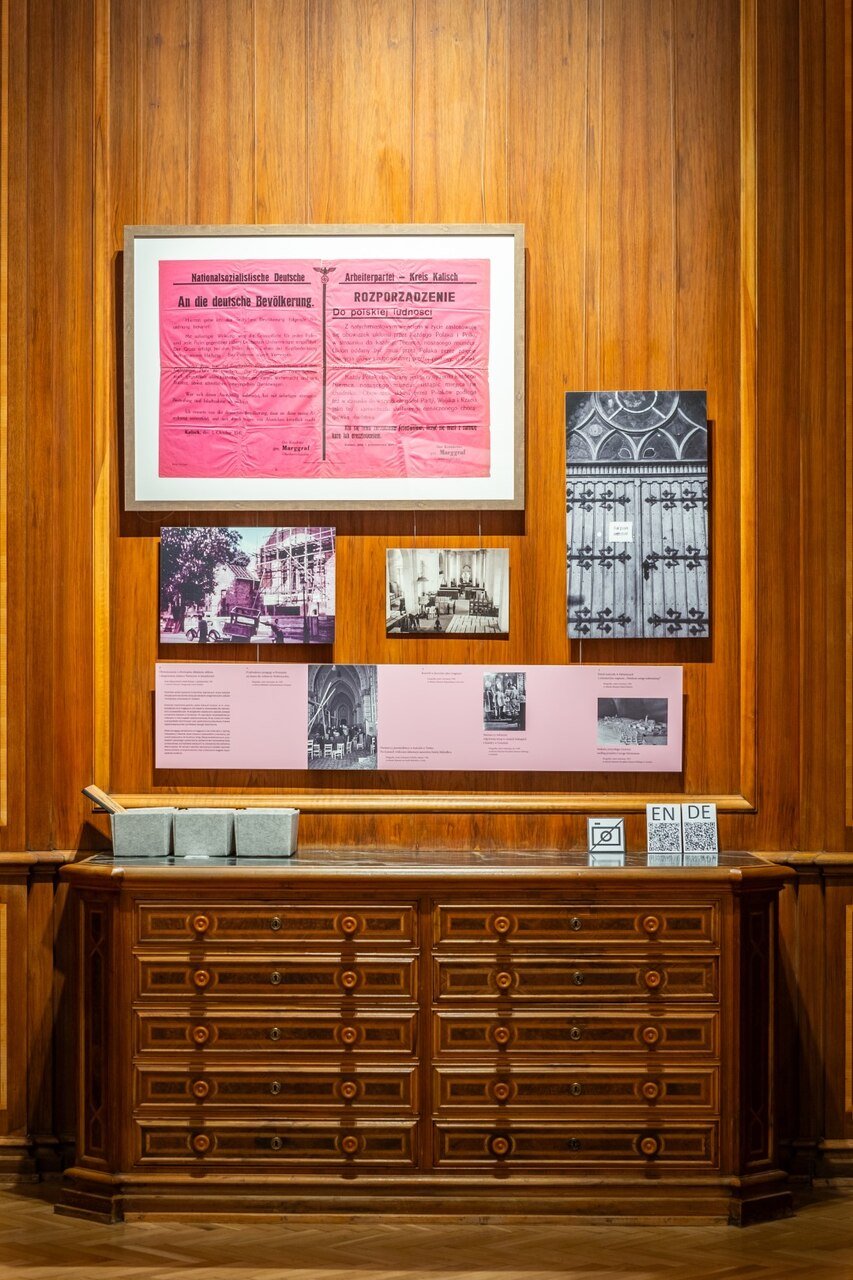

The second part of the exhibition is dedicated to the everyday life of both the occupied population and the occupiers, and is divided into three thematic sections: City, Interiors, and Landscape. Items such as porcelain, furniture, and banners bearing the insignia of the new Nazi regime, collected from private owners and borrowed from numerous museums, archives, and libraries are presented in three historical rooms – the Walnut Room, the Birch Room, and the Marble Room. The objects testify to the symbolic takeover of not only public spaces and gestures, but also the most intimate ones, such as eating from plates with swastikas on them.

The fate of Poznań’s Jewish architecture is unfortunately not extensively covered in the exhibition; the Poznań synagogue is represented by a single photograph in the second part of the exhibition and is juxtaposed with images of churches that were converted for utilitarian purposes. But unlike the Jewish temple, the churches were restored after the war and their sacral function was reinstated. This lack of distinction between Polish (Catholic) and Polish Jewish heritage is a problematic curatorial decision, as it does not question the use and memory of this “troublesome legacy” after the end of the German occupation, for which the postwar Polish authorities, including local governments, are responsible. It is not such an issue when it comes to pointing out the different fates of the occupied populations during the war. The exhibition clearly shows that Jews (not catholic Poles) were herded into ghettos and murdered in the Kulmhof extermination camp, and that Jewish gravestones were used for construction purposes, and not Catholic ones.

The third and final part of the exhibition is a recording of a radio play by Fundacja Fonorama, based on readings of excerpts from Zygmunt Krzyżanowski’s 1939 short story “Yellow Coal,” and an installation by artist Iza Tarasewicz referring to the same text, placed in a room once prepared for Hitler’s office (the Fireplace Room). Both works are symbolic, contemporary commentaries on the historical exhibition. Krzyżanowski describes the titular coal as an alternative source of energy derived from anger, the greatest outburst of which occurs during wartime. Tarasewicz visualises this energy in the form of yellow clay bricks weighing almost a ton. Arranged on flat metal forms laid out on the marble floor of the spacious room, they resemble a model of a destroyed city in the aftermath of war and the enormous energy of hatred it unleashes. This concern is followed by the question of how to deal with the legacy of war and the crimes inscribed in buildings and streets, or buried at the bottom of lakes.

Is it possible to integrate this legacy into the everyday, practical use of the infrastructure left behind by the occupiers? Would it not be more appropriate, where possible, to step back and let these memories of past crimes speak? These and other questions accompany the exhibition and are further explored in a beautifully designed and edited catalogue,[3] which, like the show itself, is dominated by the colour rose, chosen by designer Piotr Kacprzak as the element that links all of the objects and artifacts on display. The color is a response to the blood-red of the Nazi flag, a faded memory that the third and fourth generations after the war can now speak of without fear, but also with an awareness that this repressed history is returning. Paradowska and her colleagues have done a tremendous amount of work centering the memories of such architecture, which functions as a witness and sometimes an ally, which helps to work through the ballast of history in order to confront rather than repress, and to ensure that it does not quietly fade away.

[1] I would like to thank Max for pointing this out.

[2] In the Wartheland, the largest ghetto was in Łódź (Litzmannstadt); in Poznań, labour camps were established, not ghettos, such as the one at the Edmund Szyc Stadium.

[3] The catalogue can be bought on the spot in Zamek or ordered online by writing toon: iluzjewszechwladzy@ckzamek.pl

Artist: Fundacja Fonorama, Iza Tarasewicz

Exhibition Title: Illusions of Omnipotence: Architecture and Daily Life under German Occupation

Curated by: Aleksandra Paradowska

Venue: CK Zamek (ZAMEK Culture Centre in Poznań)

Place (Country/Location): Poznań, Poland

Dates: 18.10.2024 – 09.02.2025

Photos: M. Kaczyński