Joachim Aagaard Friis

How do you represent generational trauma through art? How can you address the suffering inherent in these wounds, aesthetically? And, adding to the complexity, how do you represent these artistic negotiations of historical and present traumas in an exhibition setting that connects different – and sometimes seemingly incompatible – political and cultural perspectives? This is not an easy task, but curators Margaret Tali and Ieva Astahovska set out to do exactly that in the exhibition Difficult Pasts. Connected Worlds, which was on view at Tallinn Art Hall’s dashingly pink satellite gallery located in the suburban district of Lasnamäe in East Tallinn. Thirteen artists were included in the exhibition from a wide range of geographical contexts, and what seemingly ties these artists together is their relation to a northeastern context, primarily Scandinavia, Russia, and the Baltic countries.

The curatorial approach behind connecting traumas across historical and geographical divides builds on the hope that art can create new connections between violent histories that have generally been considered incapable of being perceived together. The curators envision that the bridging of East and West, past and present, and the spectrum of difficult individual and collective memories, can cultivate and strengthen forms of solidarity, resistance, and empathy.

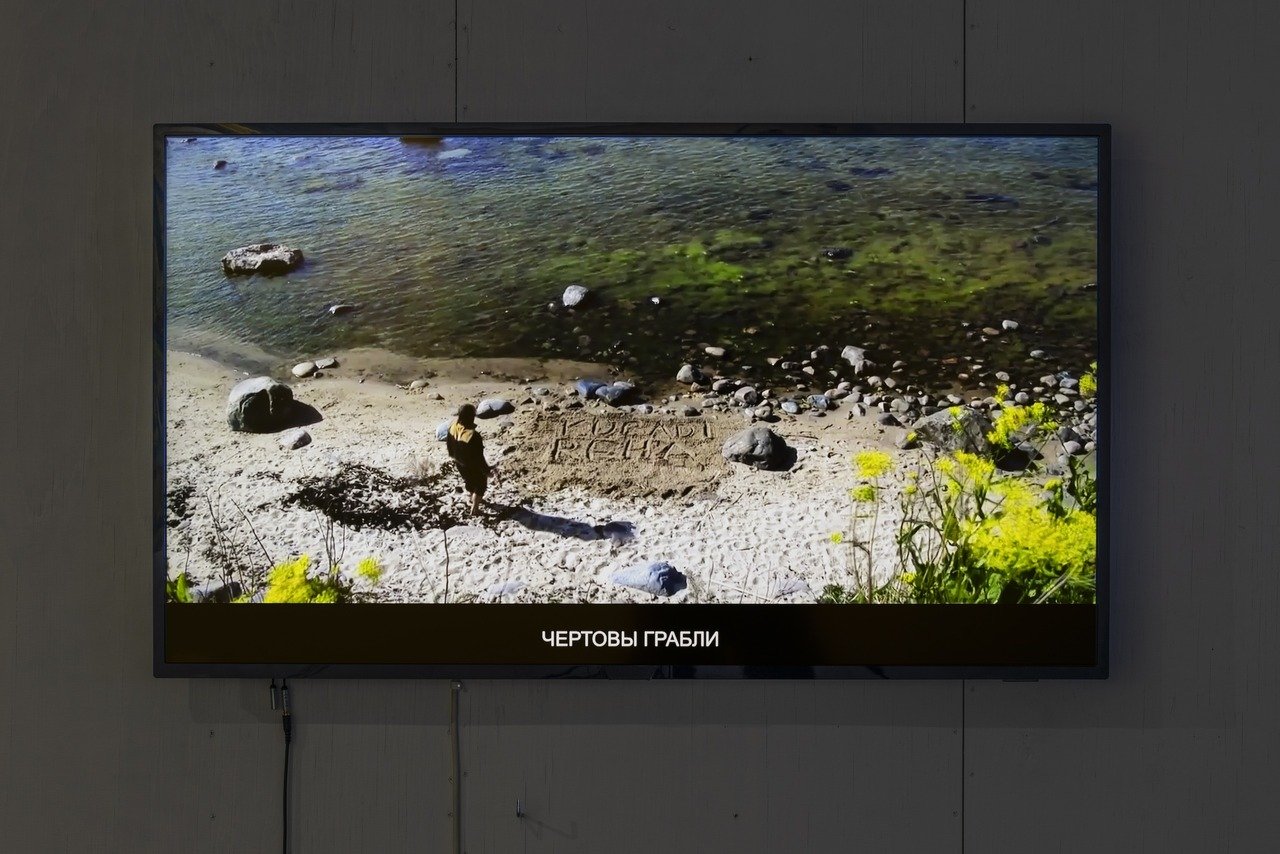

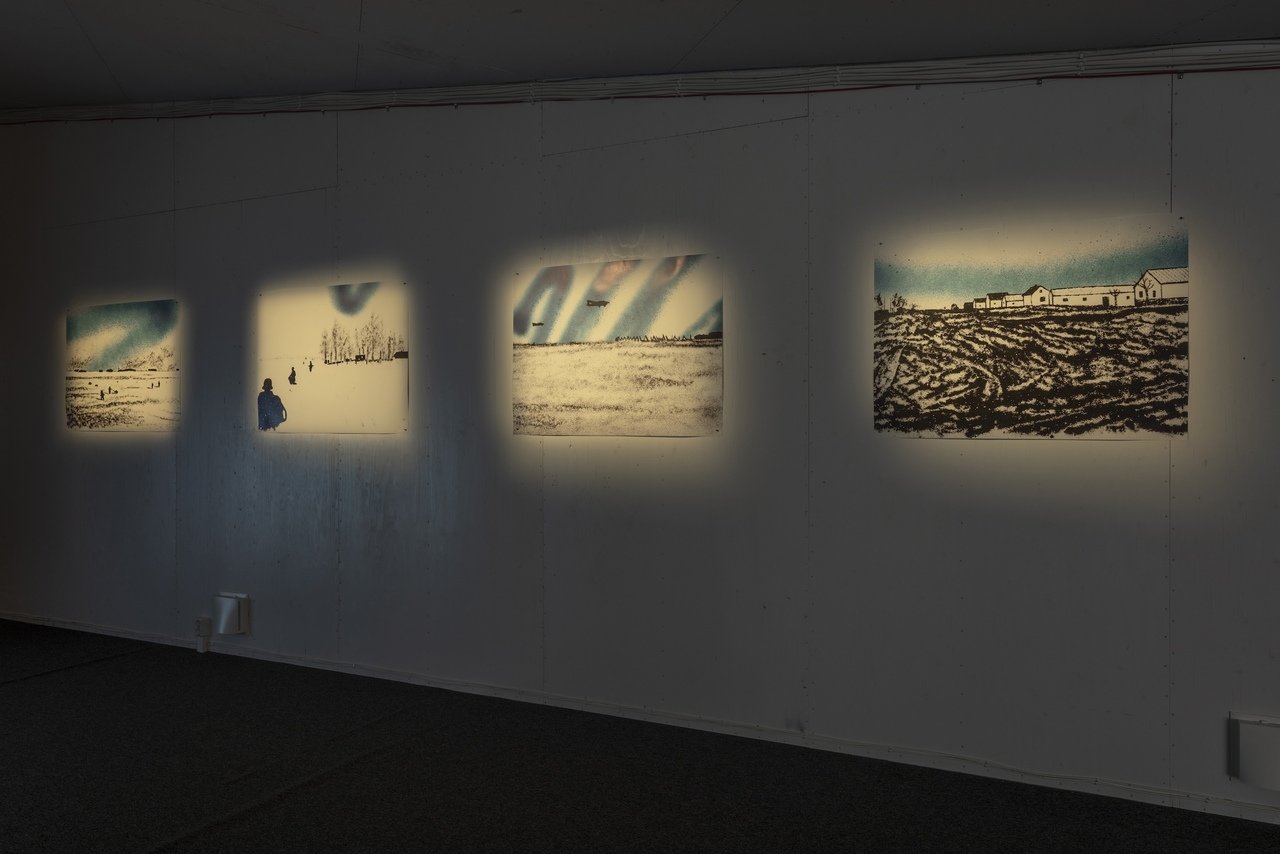

The pavilion is constructed with a small, central courtyard, and the artworks are displayed in a rectangular pathway around this square. As such, it is only possible to see a few parts of the exhibition at a time, with some of the artworks’ sounds echoing throughout the pavilion, since it is essentially just one big room. This design connects the artistic contributions on an aural level that fits nicely with the theme. However, despite this design and the praiseworthy thematic aims, the exhibition begins on a somewhat underwhelming note. Estonian artist Tanel Rander’s performative works Damn Rake (2023) focus on his efforts to learn German in Berlin and his “subconscious” resistance to this learning due to centuries of German colonial power. His works are not uninteresting, but considering the emotional weight of the rest of the exhibition, their conceptuality seems a bit out of tune in the overall framework. I think this has to do with the fact that Rander explores his own relations to colonial history, whereas many of the other artworks take a careful look at the suffering of others, bringing it into the minds of the audience in poignant ways. This makes Randers’ work seem markedly different, and it therefore gives me a mistaken first impression of the exhibition. The contrast is quite evident at the end of the exhibition which is marked by Lia Dostlieva and Andri Dostliev’s work Black on Prussian Blue (2020). In a series of drawings, the two artists have reinterpreted photographs from a German Nazi soldier during the Second World War. The violent gaze of the soldier is disclosed by the difference in motifs: from Western Europe we see cultural heritage such as temples, cathedrals, and castles, whereas the motifs from Eastern Europe are primarily close-ups from muddy fields. However, the artists have turned this power dynamic a bit on its head by enlarging the muddy fields to stand-alone artworks whereas the soldier’s photographs of Western European landmarks are minimized to tiny drawings shown in a four-by-four grid.

After Damn Rake, my eyes are quickly caught by the next installation, a collection of paintings and sculptural objects by the artist collective Family Connections (Glenda Martinus, Rudsel Martinus, Jörgen Gario, Quinsy Gario) from the Netherlands and Curaçao. In the narrative of this installation, the connection of different and largely forgotten colonial pasts are front and center. The story of a Sudanese general from a 3rd century Roman army, who was a patron saint for centuries afterwards in the Baltic countries, is connected to a fictional story of a Maroon leader in Jamaica, written by Estonian writer Lydia Koidula in 1870. The stories are interestingly connected both to diverse colonial pasts and to the Estonian context of the exhibition. Importantly, the stories in the artworks emphasize a nuanced solidarity, which is tempered by other less heroic modes of thought such as objectification and glorification. In one painting there is a group of Black men smiling and raising their arms in a seeming gesture of community. In another, painted almost abstractly, silhouettes of naked female bodies are visible in the mesh of blue, green, and brown colors. Indicators of historical references in these artworks are vague, however, and in general, it is hard to extract the conceptuality from the aesthetics in Family Connections’ contribution to the exhibition.

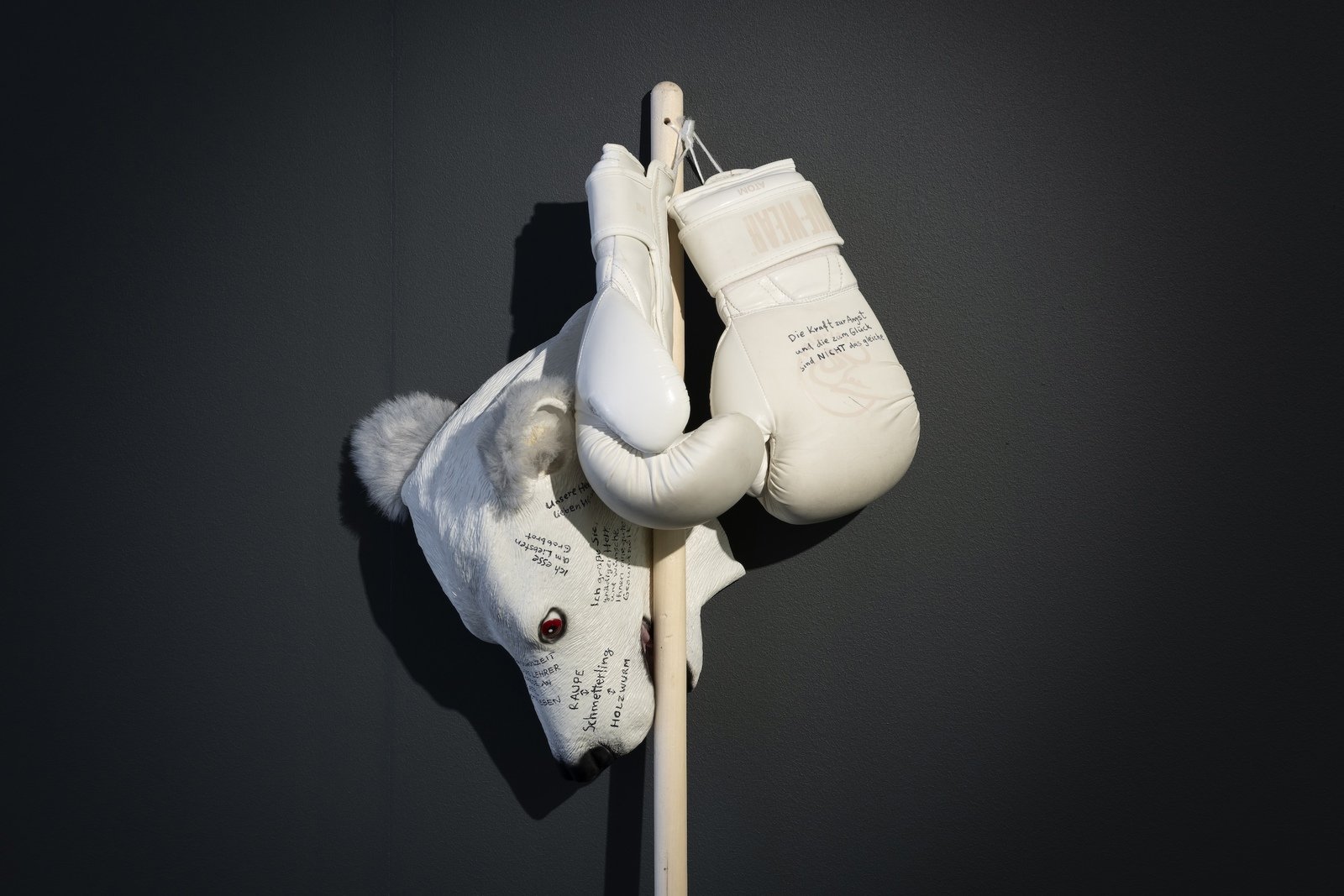

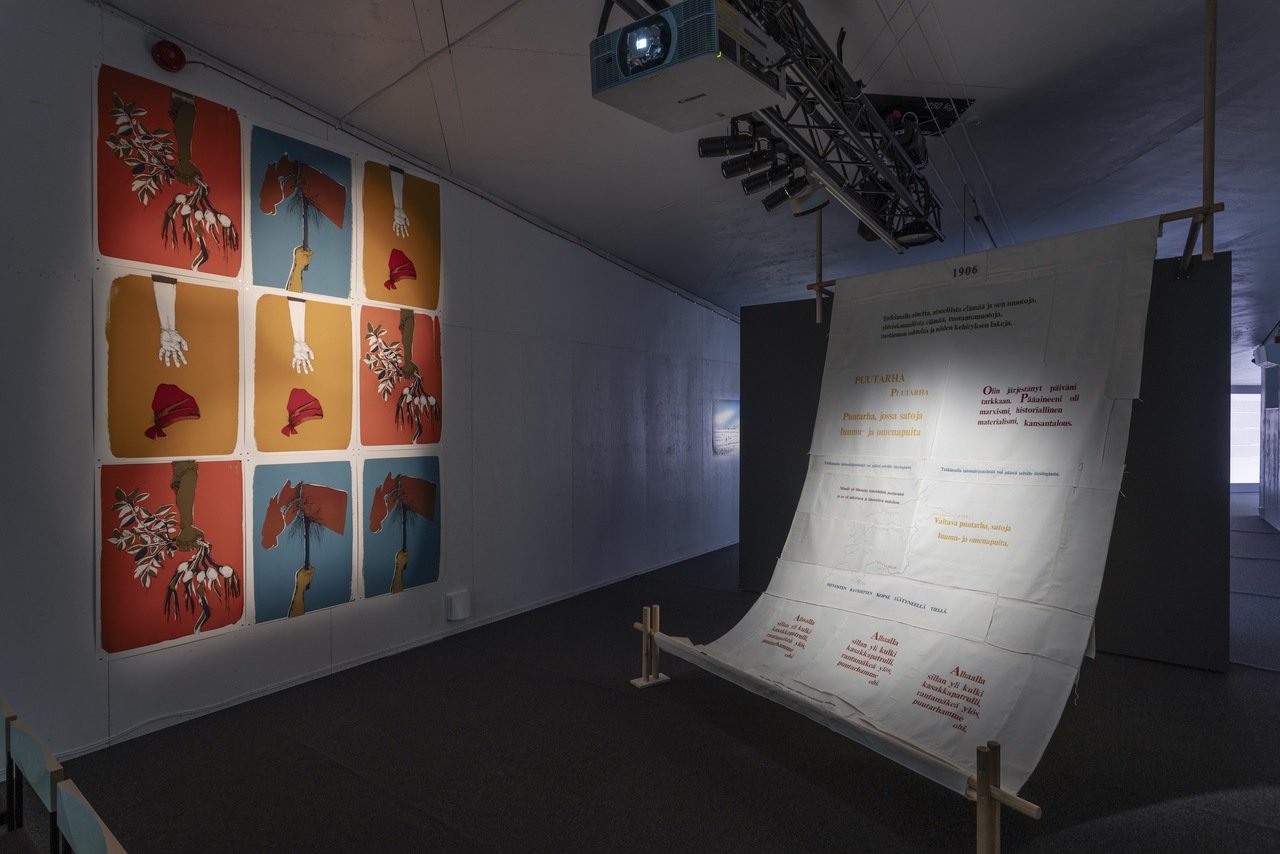

From here, the artworks become more immersive with aural and cinematic qualities. French-Estonian artist Eléonore de Montesquiou’s installation 33 Monsters (2022) is a complex monument to the Russian writer Lydia Zinovieva-Annibal’s eponymous novel from 1907. Recently republished in English by Montesquiou, the novel depicts lesbian desire, but also more ambivalent power dynamics between queer people. In addition to this overarching framework, the artwork thematizes Lydia’s self-chosen surname, Annibal, which was supposedly a tribute to a Black man from whom she descended. The fact that Montesquiou herself descends from Annibal makes the whole artwork an intricate web of complex connections across suppressed identities throughout time. The artwork quotes Annibal’s diary-based novel, printed on textiles that hang around a wooden structure which is constructed like a little hut that you can enter. Inside, more quotes, photographs, drawings, and other paraphernalia are gathered. These objects also act as an homage to the writer, who was largely forgotten because of her sexual identity.

As is evident already, many of the artworks of Difficult Pasts. Connected Worlds are microcosms of complex connections between geographies, identities, contemporary issues, and colonialism. However, this web-like narrative approach is broken in Vika Eksta’s gripping video Conversations with Dad (2020). In this work, she and her dad talk about his time as a Soviet soldier engaged in the Soviet-Afghan war (1979-1989), the most brutal military conflict of the late Soviet period, where over three million people on the Afghan side died while the Soviet army lost only 15,000 soldiers. As the catalogue explains, the American concept of “Vietnam syndrome” – now more generally understood as post-traumatic stress syndrome – was not commonly discussed in the USSR, and the silent suffering of homecoming soldiers was rather praised as “masculine silence.” All these aspects of the war are present in the video, alongside a tender feeling which emerges from the artist’s wish for familial closeness. This feeling becomes even stronger when we get to know that this is the first time the artist and her father have really discussed his military past.

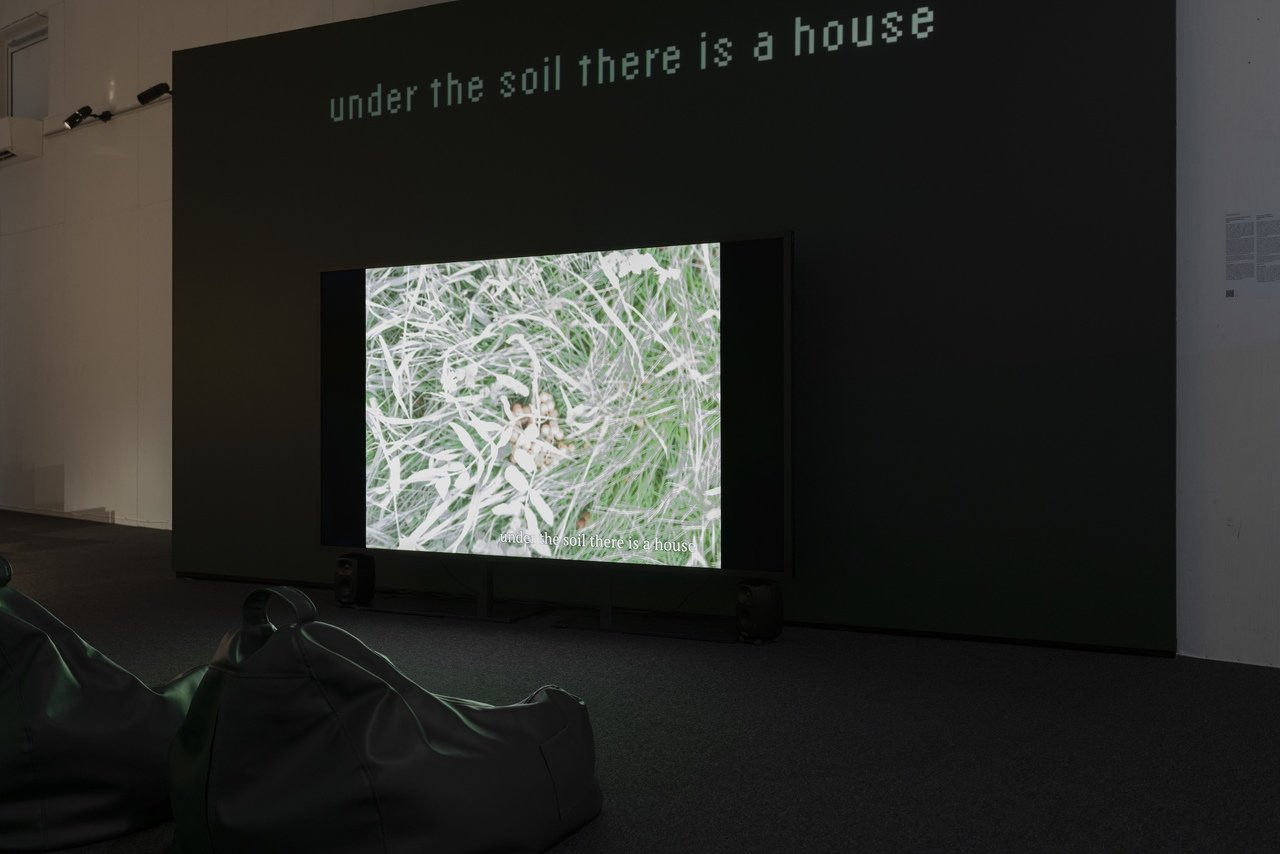

In a completely different context, but in the vicinity of the same geographical territory and family-related approach, Yaniya Mikhalina investigates the long durée of Russian imperialism and its transgenerational influences on the Tatar community. Reviving her grandmother’s old songs and clothes in the video installation Munajats of Mähira (2024), Mikhalina honours indigenous Tatar practices. Her grandmother Mähira lived through two world wars and the communist regime but stayed close to religious and indigenous practices her whole life. Lying down on a group of large pillows in front of the video screen, the audience can take in these melodies in a dimly lit area of the exhibition. Hearing and seeing these practices being carried on by Mikhalina in the form of the munajat is a strong and healing experience of vulnerable resistance.

But of course, this healing experience can also be problematic. I am reminded of Susan Sontag’s writings on representing the pain of others through visual art – and if it can wear out our moral feelings. On the one hand, artistic narrative and framing contextualize the images in artworks to give them most of their meaning. But on the other hand, as Sontag writes, those who have not lived through the pain represented cannot understand and imagine the experiences such images represent. In the case of this exhibition, I would change the word from pain to suffering since it is not the photographic moment of pain that is portrayed, but the generational wounds or painful experiences across decades or even centuries-long timescales. The dilemmas of their representations are nonetheless just as pertinent as those that Sontag grappled with. How can these artworks engender empathy for such historical traumas – of colonialism, war, political regimes, suppression of minorities – in the ways that they deserve? I don’t think, like Sontag suggests, that these artworks desensitize us to the violence, but I do think that it is important to be careful about claiming what kinds of empathy and solidarity they can create.

One of my favorite artworks in the exhibition, Jaana Kokko’s Roma mountain (2022), is a sort of ethnographic following of the suffering of people marked by different types of colonialism in a very specific geographical place. Here, the end goal is not clear from the beginning. Kokko’s video work took its point of departure from the legacies of Finnish-Estonian writer and leftist politician Hella Wuolijoki who lived in the city of Valka / Valga on the border between Estonia and Latvia. But during the interviews she conducted with current female inhabitants of the city, Kokko gives time and space to these women and their stories about their everyday life and work. During this process, she diverges from her initial focus. A separate theme of the work becomes what many of these women mention, the disappearance of Roma people in the neighbourhood. In a devastatingly vulnerable and honest account, a local Roma woman called Bergitta tells of her family’s losses to the Nazi genocide against Roma people in this area. At the same time, motherhood – the artist’s own and the women she interviews – also becomes a heartfelt theme, especially since their daughters are often present at the interviews; they roam around, play with the technical equipment, their youthful perspectives incorporated as a hopeful element of the work.

Kokko’s film is an excellent example of the exhibition’s utopian aim to sensitively cultivate a conversation about many difficult, but also life-affirming, themes at the same time, in an effort to connect seemingly incompatible temporalities and identities in a way that only art is capable of. This exploratory and open-ended approach is not without its problems; for example it can unintentionally wipe out important details of each historical context. But in its own right, it is an empathetic way of making us aware of unacknowledged traumas of the past without desensitizing us to the pains that they have caused.

The exhibition was previously presented at the Latvian National Museum of Art in Riga in 2020 and the National Gallery of Art in Vilnius in 2022. Co-organized by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art.

Artists: Lia Dostlieva and Andri Dostliev, Family Connection, Vika Eksta, Zuzanna Hertzberg, Jaana Kokko, Paulina Pukyte, Yaniya Mikhalina, Eleonore de Montesquiou, and Tanel Rander.

Exhibition Title: Difficult Pasts. Connected Worlds

Curated by: Margaret Tali and Ieva Astahovska

Venue: Tallinn Art Hall, Lasnamäe Pavilion

Place (Country/Location): Tallinn, Estonia

Dates: 10.08–20.10.2024