Fadescha in conversation with Tadas Zaronskis

In June 2024, Party Office (Vidisha-Fadescha) curated the exhibition RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III at Nida Art Colony of Vilnius Academy of Arts. In this conversation with Tadas Zaronskis that took place on July 16th, 2024, Fadescha shares how they expand their project “Qworkholics Anonymous” into the residency and the exhibition at Nida Art Colony.

Tadas Zaronskis: You created the platform Party Office, which is an anti-caste, anti-racist, trans-feminist art and social spacetime, founded in 2020 in New Delhi. The current exhibition RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III, which you curated via Party Office, is the third iteration of the Qworkaholics Anonymous sequence. The second iteration was presented at documenta fifteen (Kassel, Germany) in 2022 as a video titled Nesting in Rapid Floods: Qworkaholics Anonymous II. Could you tell me more about the origin of Qworkaholics Anonymous and the origin of Party Office?

Fadescha: In India, all major art spaces are led by commercial interests. In the 90s, the Triangle Arts Network set up some alternative spaces in South Asia: Khoj International Artists’ Association in New Delhi (1997), Vasl in Karachi (1999), Theertha in Sri Lanka (2000) and Britto Arts Trust in Bangladesh (2002). For me queer activism and going into the space of professional art were simultaneous, this happened around 2007. At the time there was a fight against Article 377, a British act that criminalised homosexuality in India, and I was working with many alternative spaces and also thinking about how being queer means different things depending on context. In India, access to healthcare, education, and other stuff depends on your caste. The caste system is referred to in Rigveda, and then codified in Manusmriti, an ancient text from the first to the third century used in matters of law, social conduct, and virtue.

The caste system is still at the core of the social fabric of South Asia and its diaspora, across religions. The Brahmins are the academics. The second one are the Kshatriyas, which are the warriors or the kings, or the monarchy. Vaishyas are the business people and traders, and Shudras are peasants or the servant caste. And then we have the Dalits, who are outside of the Varna system, they are made to do manual scavenging. These occupations still exist within India without having had any technological development. People from lower castes do not have similar access to education. My ancestors, Jyotiba Phule and Savitri Bai Phule were the first ones who started schools for excluded caste communities, as well as the first school for women. It is significant when someone from a lower caste position can direct an organisation – especially an artistic or educational one. These are the intersections and the complexities.

I was working in various organisations, and felt that there was not enough agency, as if what needed to be said was always translated into something palatable. Personal agency is a very important thing. So at Party Office we work with people who are speaking from the first person perspective, through their lived experiences, and are coming from Other Backward Castes or racialised communities. In 2019 Modi was elected for a second term. I was working in nightlife for a few years before that – because it was not possible to survive doing only arts. At that moment, other artists were also connecting nightlife and art, which used to be separate, like the Asian Dope Boys. In 2019, I was at a residency in Beijing where we performed at Beijing Art Week. I also collaborated with a collective called Hyperbation, we presented The Hyper Rave of Queer Maximalism, a virtual reality rave. After this, people started inviting me to art spaces while I also performed as a DJ and sound artist. And I thought that it was becoming urgent to open a new space in India, there was a need for a new political imagination, a place where we could come together as dissidents and queer bodies.

TZ: If I understand correctly, although you operate under Party Office elsewhere when you work on various projects, it exists first and foremost as a very concrete and physical place in New Delhi?

F: Party Office in New Delhi was my home. I was organising nightlife, and I formed a collective of trans and non-binary people. And I thought: why am I making money for these clubs when everything is ours – the people who come, the people who play? There was also a generational gap where young people coming to clubs were not meeting the elders of the same community, so that’s another reason why we needed our own space.

In late December 2019, there were protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act, a law with regards to citizenship that legitimises discrimination on the basis of religion, disallowing people who are Muslims, especially refugees, to become a part of the Nation-state. There were several protests, 24/7 sit-ins organised across the country led by Muslim women. My plan was to open on January 22, 2020. At that moment, Arshia Fatima Haq, an artist from Hyderabad (India) living in Los Angeles was visiting Delhi. She was archiving sounds from the protests. And so, Party Office opened with Discostan: The Psychedelic Islamic State.

The name Party Office comes from the office of a political party. “Party” relates to the collective, a space for gathering, and “Office” is more about the building, the architecture – meaning not only the material part but the architecture of the institution, its structure. Party Office was also necessary because for me, anarchist practice is about creating what I want rather than only rejecting what we don’t want. We are constantly rejecting, but we also have to create and self-organize. On my website you can see the manifesto and a semi-fictional illustration of Party Office, which I commissioned from artist Jonathan Eden, whose practice centres on making space for disabled and divergent bodies. The details are very specific: here in the living room are anti-caste social activists from India of different generations. The two standing beside each other are Thanthai Periyar and Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. Periyar started the Self-Respect Movement and the Dravida Kazhagam party. In 1922, Periyar first declared his intention to burn the Ramayana and Manusmriti, literature that upholds caste hegemony. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who was head of the assembly, which wrote the Indian constitution on September 2, 1953, said that if they don’t agree to amend the constitution to serve the marginalised he will be the first one to burn the constitution. The one walking in from the balcony is Mahatma Jyotiba Phule, he was the founder of Satyashodhak Samaj (Society of Truth Seekers) to attain equal rights for people from lower castes, and was the author of the book Gulamgiri (Slavery) published in 1873. He claimed that education was important for the emancipation of lower castes. He also taught his wife, Savitri Bai Phule. Savitri Bai is sitting at the dining table. In 1848 they both started the first indigenously-run school for women, they both are my caste ancestors. Savitri was also a pioneer of the feminist movement in India, as well as a poet, who wrote the famous poem Go, Get Education in 1892. Fatima Sheikh is in blue, sitting on the couch – she was also helping them with the school. She was the first female Muslim woman teacher in India. Beside Fatima Sheikh, Phoolan Devi (also called the Bandit Queen), was a politician and a dacoit. She faced sexual abuse as a child and eventually joined a gang of dacoits. They would loot higher-caste villages. She even punished her rapists. She lived between 1963 and 2001. Beside Phoolan Devi is Birsa Munda, who lived between 1875 and 1900; he was an indigenous independence activist. Birsa Munda advised tribal people to pursue their original traditional tribal religious systems instead of converting to Christianity. Birsa responded to the challenges of agrarian breakdown and culture change with a series of revolts and uprisings that were organised under his leadership. Beside Savitri, you also see a blue panther, which is a symbol of the Dalit Panthers, a social organisation to combat caste discrimination in India which started in 1972, inspired by the Black Panthers in the USA.

You can also see a millet crop. My father and sister are farming, they propose that millet should be used as a biodiverse grain. We have lost it culturally to rice and wheat produced in the green revolution. In other spaces you can see a dark room, a DJ table, my dog, toys, my wisdom teeth, and other things that are part of the imagination of this home.

TZ: So your history as an artist and curator is closely connected to your political and social work.

F: Socio-political events fuel some of my writing. Though, for me, protest is an everyday praxis, not only something one does as a staged public gesture. During COVID, I was mostly raising money for people who I was/had worked with. The raven/crow icon we use in the graphics of the exhibition RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III is the crow that attacked the peace doves in 2014 at the Vatican, when the Pope released them with a message of peace for Ukraine. It was another example of hollow political posturing replacing actual support for Ukraine. This is the difference between security and safety. The police protect the state, and the state security infrastructure is created to surveille, punish and discipline, just like the borders. The raven represents collectivity against the false white gesture of peace. It’s like when a bunch of small fish come together to bite the big fish. It is also a critique of white institutions, a way to action our dissatisfaction.

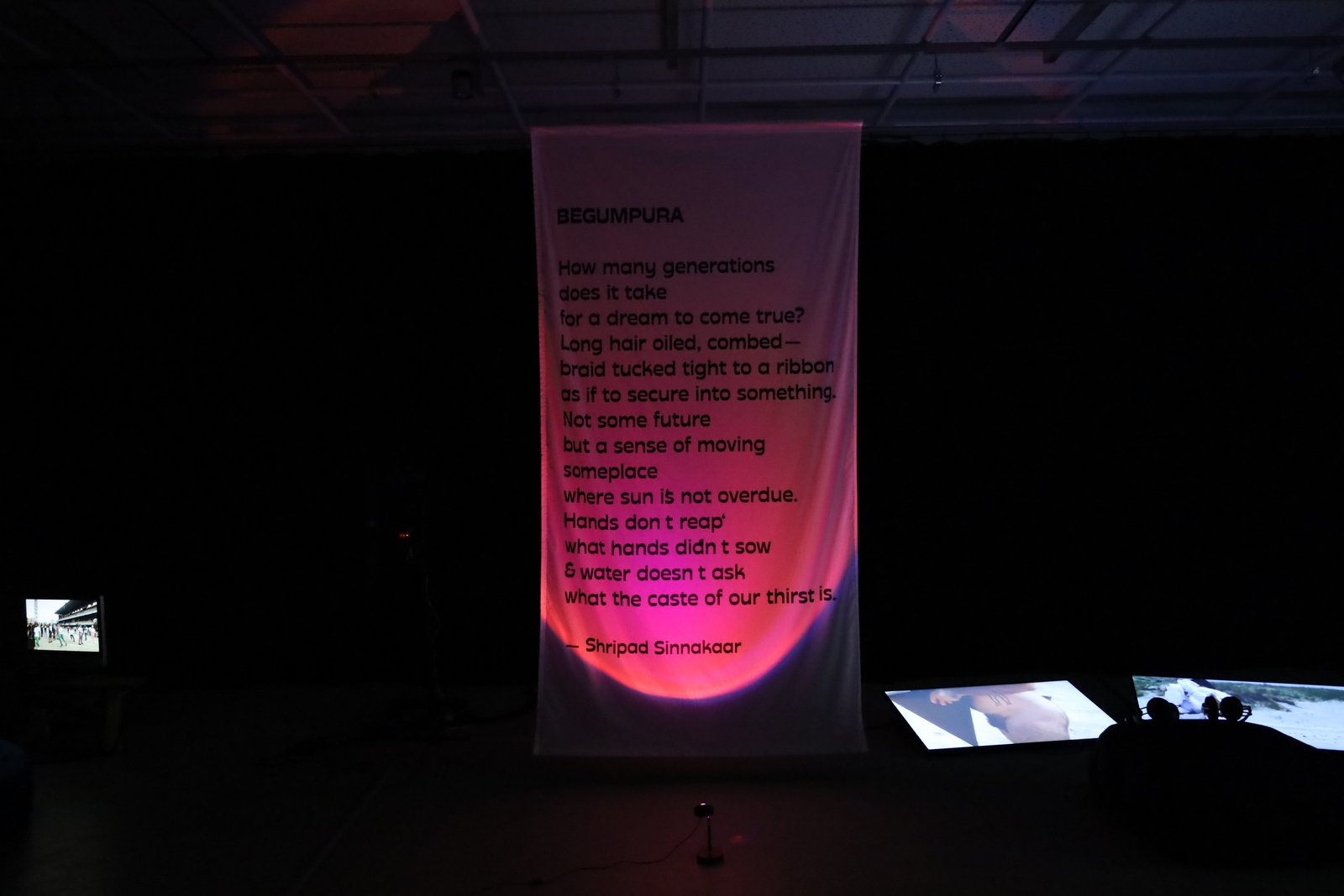

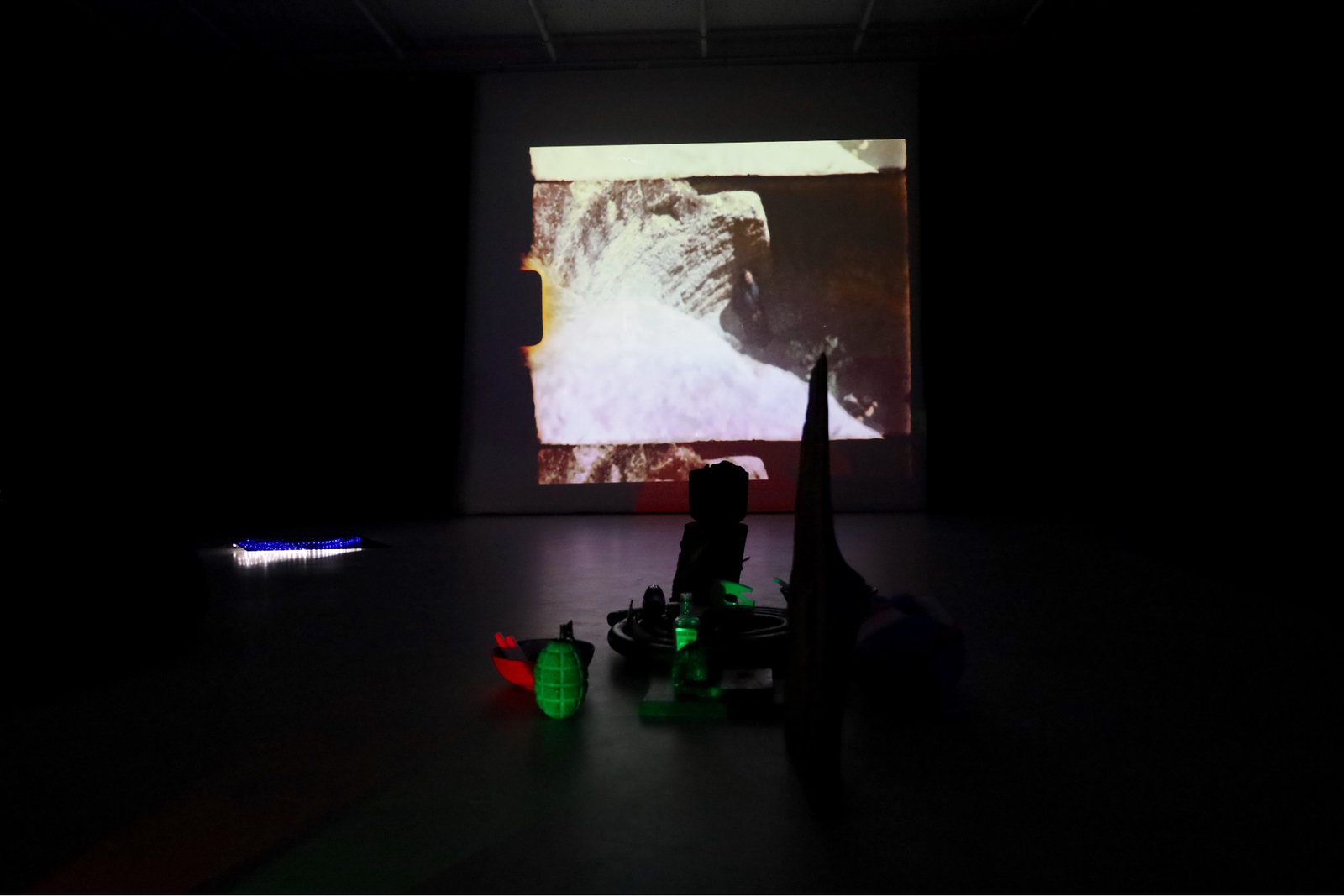

TZ: I’d like to ask you about another aspect that is very present in the exhibition RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE. You mentioned religion and its critique, and this need for an anarchist practice to not be limited to critique, but also to create alternative, autonomous structures. I had this feeling that a certain critical spirituality or counter-spirituality was present in the exhibition. Also the meditative, magical elements seem to be very central. I would like to highlight a few things in particular: we are greeted by the Spell against fascists by Mihaela Drăgan. In the centre of the exhibition we find a small queer-trans altar (gathered from objects, ruins, signs of war). Shripad Sinnakar’s poem touches upon the critique of Brahmanism and caste. Anna Ehrenstein’s Hypnotization of the cloud offers a seance of hypnotic meditation in order to clean our subconscious of the nationalist and colonialist propaganda structures. Pêdra Costa works with the natural elements of earth and water in Brazil, and in Nida, while tracing a complex spiritual connection of the natural and military history of these places. And the 12 steps of Qworkaholics Anonymous which you wrote, appeals to the metaphysical connection to ourselves and to the ancestors as a means of healing and fighting and resistance. There are of course many other elements of spirituality. So I’d like to ask, what role does spirituality play in your curatorial and artistic praxis? How is it to be understood, between the critique of established religions and the affirmation of different kinds of spirituality? In the context of the exhibition it seems to be one of the central elements of community building and re-conquering that which has been lost to the colonialist world order.

F: Yeah, I think it’s spirituality more than religion for me. The 12 steps of Qworkaholics Anonymous [Fadescha, 2024] embraces spirituality. Sufi mystic Rumi writes: “Work in the invisible world at least as hard as you do in the visible.” In my view, following our instinct is one of the core human characteristics that capitalism takes away from us. As we witness in the current televising of the genocide – people no longer know which way to run or in which hand to hold their child because they don’t know where the bomb is going to fall or where the bullet is targeted. I think at that moment it’s about faith and resistance. Due to the global rise of Islamophobia, and also experiencing the protests held in Delhi led by Muslim women in 2019 and 2020, Islam has played a large role for us in thinking about faith, as one believes Allah cares for you and gives you strength to protect yourself, but also to come to him. Writer Octavia Butler also talks about spirituality in Parable of the Sower (1993), it’s a kind of post-apocalyptic novel where a small, closed community is being attacked, and the character Lauren Olamina invents a new kind of spirituality to protect people, and moves away to find a new community based on her religion called the Earthseed. bell hooks talks about how during the Vietnam war, Zen Buddhism emerged as a way for the society to be able to survive, and have faith; she followed the writings of Tich-Naht-Hanh.

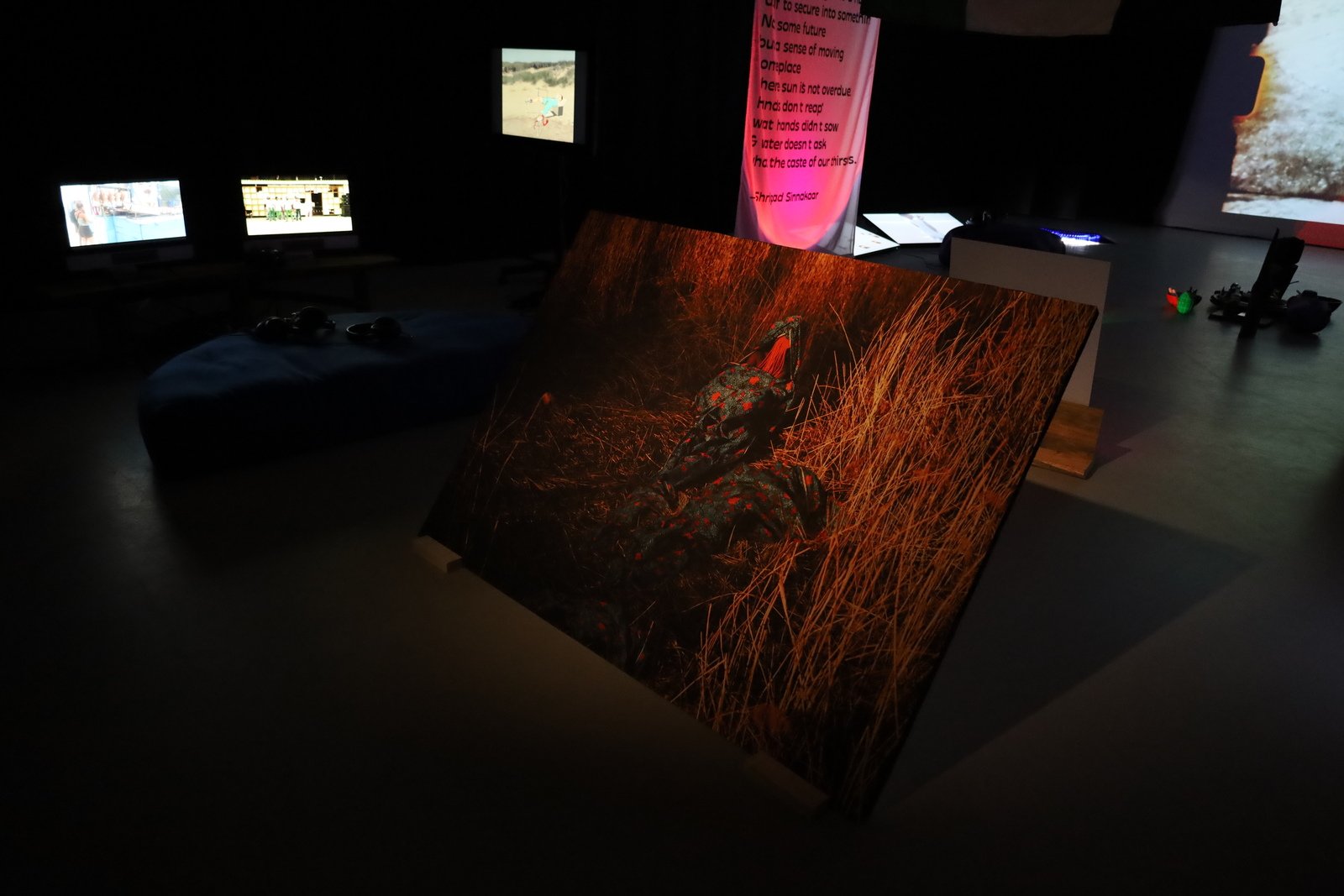

In neoliberalism, everybody becomes an atheist. Or religion is used within the political system to control and to establish identity, which is then weaponized. For me, spirituality has to do with space and time and visualisation. I do hypnosis; it makes you focus on what’s happening within, shows you your own possibilities, and offers an expansive experience. It also allows you to find grounding and safety where there isn’t one physically. Of course it is possible to use anything for and against each other, it’s also the question of what practice you have and what practice is an ethical one. In Europe everything is about control, about the idea that humans are superior beings. There is a kind of stigmatisation of witchcraft and of Paganism as well. The raven and the crow are companions of witches. We created the altar in the exhibition, because for some people in the residency, primarily Blue and Pêdra, spirituality is part of their being. Blue is a Vodouist. Vodou combines practices from Western and Central Africa and was developed in Haiti in the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. It was practiced collectively in hiding, and also used within the rebellion. It is stigmatised because it is a form of Black spirituality. And there is spirituality based on elements of nature that has its own discipline which Pêdra embraces. In her performance whispers and echoes (2024) at the dunes, where sand fell over her, she later told me she felt as if she became one with it when finally covered.

For me, energy is present within all forms; objects are also witnesses. The energy is not necessarily charged in the present moment, but it’s charged by where it’s coming from. You can present a memory or fiction, and you can make drawings of things that you want within the altar – you don’t have to have them physically – the idea of them can be enough. This is the materiality of the altar. There is nothing in this world that can exist without these elements. And if one feels it is an earth element that grounds something, then we begin with that and place other elements after, but there are also other ways of doing that. The physical form of the altar is shaped by the four of us – Blue, Pêdra, Margot and I. Though we are not the only ones whose energy the altar holds, rather it is the energy of all expressions present within the exhibition. The exhibition has people speaking from different geographical positions asking for freedom; for freedom beyond their own cages, for freedom beyond their own selves. The altar then channels this energy and sinks the roots into the ground and sends it across space and time. The altar takes on the title of the exhibition, RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE, which is a collective chant for freedom. The works come from first-hand experiences of the artists and the violence imposed upon them which they seek to free themselves from.

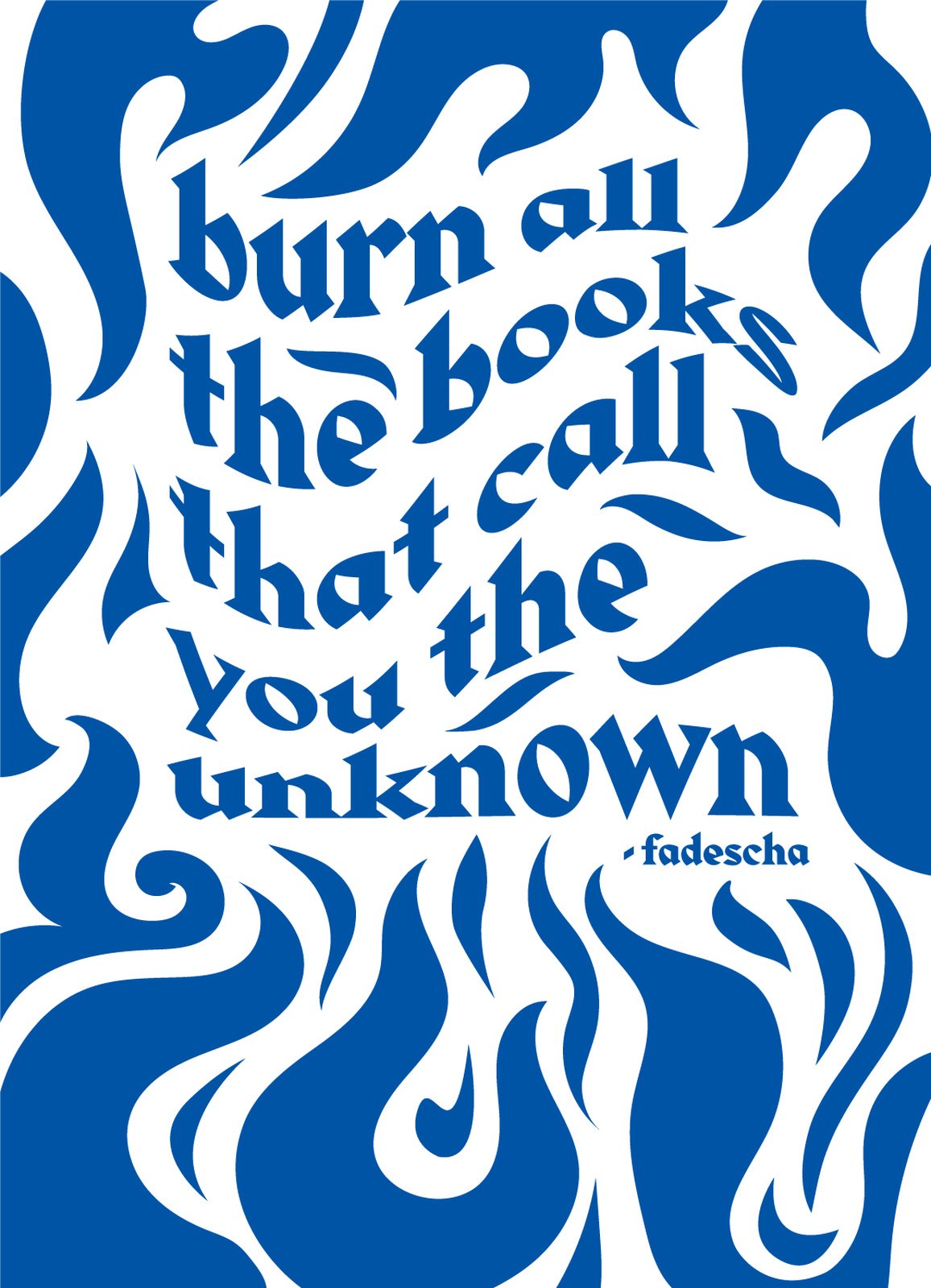

TZ: Moving further in this direction, I’d like to ask another question about the relationship between discourse and somatic or also metaphysical experience. In the presentation we read that Party Office centres queer and BIPOC people so that having an exclusive space, or even the very act of survival, can be understood as a form of resistance. You have also established a radical archive called Burn All The Books That Call You The Unknown which seems to conceptualise the act of knowledge or of remembering and archiving not as something neutral, but rather as something partial, something which can be oppressive or, on the contrary, helpful in resisting the hegemonic epistemological structures. I’d like to relate this to RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE, where a written explanation does not accompany the works: there seems to be a critique of the usual praxis of exposing, which entails explaining or presenting each work, while here, the works of art are not, so to say, protected by the explanations, and seem to interact more directly with each other and with the visitors. I wonder if you’d like to elaborate on this relation between discourse, different epistemological structures, and direct bodily, lived, or spiritual experience?

F: So, Burn All The Books That Call You The Unknown comes from chants by Periyar and Dr. Ambedkar who were represented in the Party Office illustration. Periyar said that we should burn the legal text of the caste system. And Ambedkar said that he would be the first one to burn the constitution if it stopped serving the people. My work emphasises gender and trans experience, but it is also important to critique gender and queer studies, as these fields don’t include us and our complexities. The academics from India or its diaspora are Brahmins, communities who oppress people from Backward castes; Gayatri Spivak positions herself as the subaltern while silencing the subaltern. Queer studies consider whiteness as default when they don’t talk explicitly about their race and its oppression. So we can also burn postcolonial studies and queer studies and not let it become a discipline that governs us. In the exhibition Burn All The Books That Call You The Unknown, which happened in 2020 in Sydney, there was this curtain with dots which represented the number of days women sat in protests (2019–20) against the Citizenship Amendment Act and National Register of Citizens, and the second curtain with lines marked the number of people who were killed in February 2020 because of the State-funded ethnic cleansing of Muslims in Delhi. This was the first satellite manifestation of Party Office, which included a 3-channel video work titled Burn All The Books That Call You The Unknown, the video Qworkaholics Anonymous I, and zines from queer-trans* artists.

Artists in this exhibition are presenting from distant locations. Works form a relationship, moving towards a collective desire to change things. It’s not just about here, but it’s also about elsewhere, but the elsewhere doesn’t always have to be a geographic elsewhere. The elsewhere is also the invisible elsewhere. So like in the hypnosis which Anna Ehrenstein does in RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE, we are trying to reach some place within ourselves, but it might not be physical because not everything we are is physical. There is something emotional in that, like if you look at Gabrielė’s work. The artists seek something which is creating meaning for them, where they find representation within a colonial archive. I think both Gabrielė and Blue look at the medical-industrial-complex. The photographs of Blue were taken in a psychiatric facility where they admitted themselves because of a burnout. Framing this experience, and its violence, Blue also talks about stigmatisation of the Black body, of Vodou as dangerous, ‘cause it’s of Black people, a tool which is used against colonisers. Sara Ahmed says “assuming that the stranger is any-body we don’t recognise, I have argued that strangers are those that are already recognised through techniques for differentiating between the familiar and strange in discourses such as Neighbourhood Watch and crime prevention. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the medical industry has racial, sexist and such biases as well and places fear onto people because of their behavior that seem uncanny to them.”

And that’s where the field of somatics and trauma-centered care come in as trauma is not only something physical, it’s also something that’s invisible, emotional. The idea of embodiment of trauma and its release is important in Qworkaholics Anonymous. In Aribada (N. Escobar and S. J. Paetau, 2022) – the images and symbols come from a ritual to become a Shaman, a path which offers a way of survival and a future for trans people. Similarly, Mihaela Drăgan conceptualises Roma futurism “in which Roma witches control technology and hold control over the future of mankind.” There are many such links in the exhibition.

TZ: You mentioned earlier having this critical relationship with certain kinds of decolonial and queer theory. I also had this impression that the paradigm of Qworkaholics Anonymous not only draws upon them and supplements them but also subverts them in a way.

F: I think queering for me has always been an active practice. You queer the archive by adding something to it that wasn’t considered of value by the appointed “archivist” or “institution.” It’s also possible to queer the noun “queer.” In Qworkaholics Anonymous this is multifold, queer in relation to queer survival. And who is queer? And then whose survival is queer? And queer labour, what is the labour of the queer subject? And how does the subject of labour get queered?

The 12 steps of AA (Alcoholics Anonymous) are related to the church; they want you to submit to God and only observe what he has for you, to make amends so that he provides you with your “daily bread.” But here, you are the portal for your own happening – and you can also offer something to the collective once you have done the work yourself – with the presence of others and in relation to yourself and to them.

The video Burn All The Books That Call You The Unknown sets a stage where performers dance in a white space with coloured lighting to sounds I composed from field recordings I made over the course of eight years. When we are dancing, the movements that we make come from experiences that we have absorbed, which can be from popular media, socio-cultural contexts, peer pressure, it can be multi-generational and ancestral. That’s what I like about the dance floor, there is no instruction. Of course, you might try to please people or mirror them, but you also hold onto your own subjectivies. And yet there is a collective trance at a rave that vibrates.

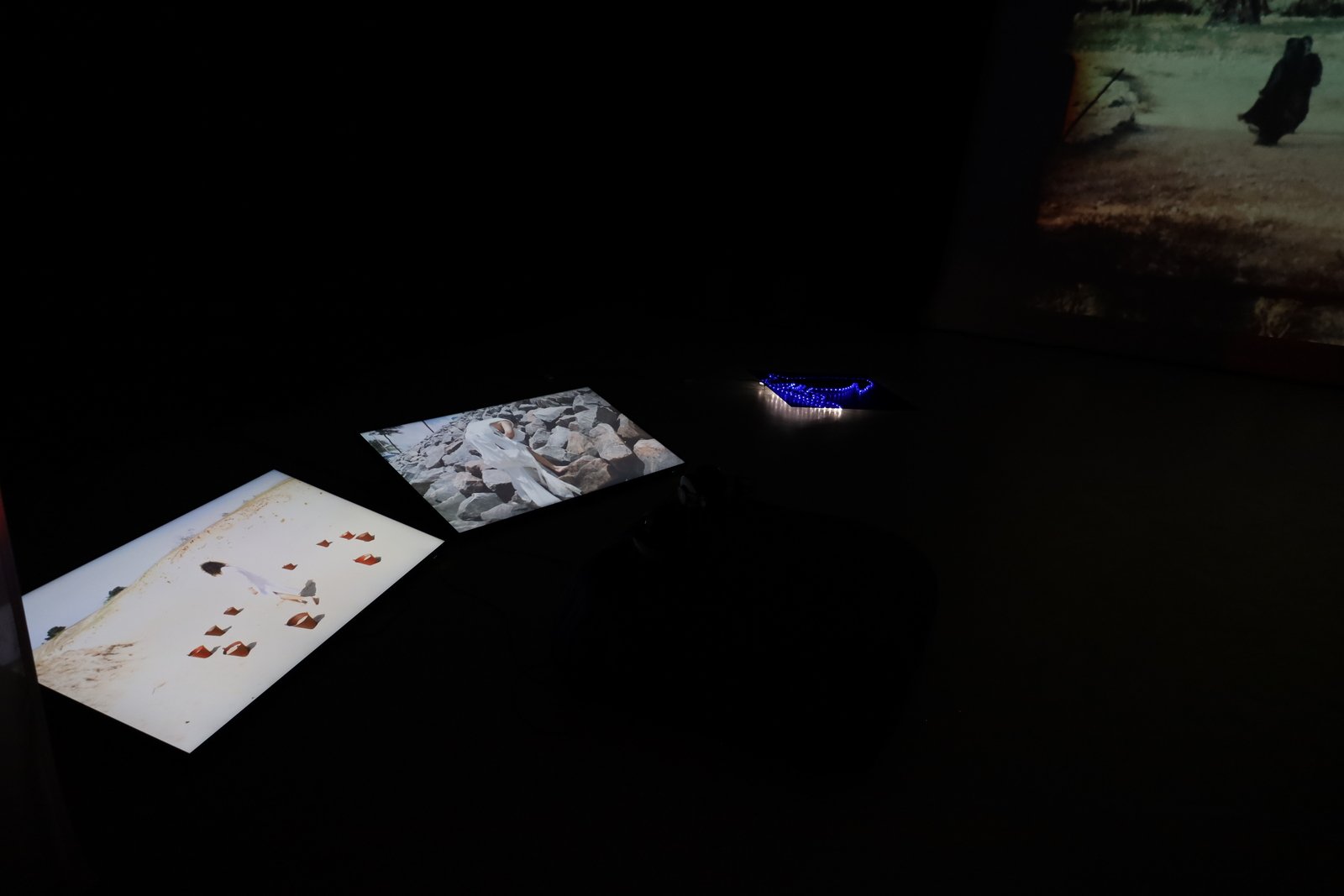

This exhibition also tries to show collectivity. The intimacy of the installation feels like people are kind of sitting together while they still stand independently and hold their complexities. The differences are there but you don’t necessarily see them, and that’s the thing with solidarity – that we keep our differences aside because we are fighting for something that affects all of us. And also, if I direct you with a text about an artist, you might think of differences because the differences are not necessarily in the work but in our colonised perceptions. So we don’t write the location from which the artist comes, you experience the work without such direction, and it resonates with you in different ways.

Vidisha-Fadescha is an artist, curator, and a cultural critic. Through a life lived of a radical gender, caste, race and disability, they suggest centring one’s pleasure and wellbeing as a liberatory practice towards abolition. Exerting Queer Anarchism, their artwork includes video, sound, text, and performance. They direct collective practices as a norm-critical pedagogy queering hegemony. Their multi-format project Qworkaholics Anonymous (2020–ongoing) asserts the very act of survival by marginalised people as Queer Labour, challenging the neo-liberal order. Burn All The Books That Call You The Unknown (2020–ongoing) are radical archives of self-representation.

Party Office is an anti-caste, anti-racist, trans-feminist, art and social space and time founded in New Delhi in 2020, which also manifests at satellite locations and as conceptual architecture. Through publications, grants, archives, conversations of life-lived, social gatherings, and more, they are building translation dialogues on empathetic futures, care community and radical agency. Party Office was founded and is directed by artist-curator Vidisha-Fadescha.

Artist(s): Anna Ehrenstein, Blue Paul Fleming, Gabriele Gervickaite, Margot Vic, Malik Irtiza, Mihaela Drăgan, Mila Kostianá, Rafiki, Noor Abed, Pêdra Costa, Queer Falafel, Shripad Sinnakaar, Simon(e) Jaikiriuma Paetau + Natalia Escobar and The Albanian Conference (Anna Ehrenstein, Fadescha, Rebecca Pokua Korang, DNA)

Exhibition Title: RESONANCE BEYOND ESCAPE: QWORKAHOLICS ANONYMOUS III

Venue: Nida Art Colony of the Vilnius Academy of Arts

Place (Country/Location): Nida, Lithuania

Dates: 15.06 – 06.10.2024

Curated by: Party Office (Vidisha-Fadescha)