Teodora Talhoș

Walking around Sarajevo, it is impossible to avoid the traces of the horrific war that took place here 30 years ago. Wherever you go, you will either stumble upon a “Sarajevo rose” – memorials made on the sidewalks where a shell exploded – or notice the bullet holes that pierce many building facades. On my first visit to the complex, multi-ethnic capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2018, I was interested in understanding how this place was both the starting place of the First World War and one of the main sites of the Bosnian War, with Sarajevo under siege for three long years. I was curious about how memory was preserved in this medium-sized city of about 300.000 inhabitants, nestled between high, green mountains. In 2018, two years before the pandemic and four years before the full-scale war in Ukraine, it seemed so distant and impossible to me that a war could take place in the middle of modern Europe. I was shocked and saddened by the realities of the wars that took place in former Yugoslavia in the 90’s, and I believed that it was a moment of confusion, madness, or evil; in any case, something that would never again be accepted within the borders of our continent. How wrong I was.

Born and raised in Romania, but having studied and lived abroad for several years, I felt a deep urge to return to my homeland shortly after the escalation of the war in Ukraine in February 2022. I wanted to be closer to home to help in any way I could, but I was also eager to understand how society, and by extension the arts, responds to such a crisis and tragedy unfolding in the immediate proximity. Knowing that the Western Balkans had a similar recent history, which is still an open wound that is not talked about often enough in the general European media discourse, it was the first place I looked for answers. This summer, I was lucky enough to be accepted to the Kuma International Summer School, an innovative program led by Italian curator and art historian Dr. Claudia Zini. The annual program aims to enable researchers from around the world to better understand the role of art in times of crisis, and to explore contemporary art practices that deal with the trauma of war, specifically in the context of Bosnia and Herzegovina. During an intense week, we had the opportunity to better understand the realities of war, the importance of multi-layered storytelling, to discover the places in Sarajevo where the memory of war and its victims are still alive, and to have discussions with artists who deal with trauma, violence, loss, and displacement in their work.

In a country like Bosnia, divided into three majority ethnic groups – Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks – with different religions – Orthodox, Catholic, Muslim – remembrance culture is performed through each faction uniquely telling its own story, which often contradicts other versions. There are several instances where monuments of the dominant ethnicity stand next to the very places where the same ethnicity committed war crimes against another faction of the community, not only demonstrating how complex the collective memory of this place is, but also continuing to inflict pain on the survivors. For me, one example stands out in particular: we were on our way to Goražde, a small, predominantly Muslim town that courageously resisted the occupation by Bosnian Serb forces during the war and thus avoided a fate similar to the neighboring town of Foča,[1] which was attacked by Serbian forces that committed massacres, rapes, and pillaging against the Muslim population. We stopped in Miljevina, an unassuming village of just a few houses, to visit the former Motel Ehos, or Motel Miljevina. Now abandoned, the brutalist structure was used as the headquarters of the local crisis committee, from where the ethnic cleansing campaign was organized.[2]A few steps away from the motel, we noticed a marble plaque commemorating what appeared to be Serbian war heroes, perhaps the same people involved in carrying out the ethnic cleansing. And just 40 minutes away in Kalinovik, you can find a mural[3] honouring Ratko Mladić, convicted war criminal and leader of the Republika Srpska army during the war.

Looking at all these painful confrontations of memory in public space, but also thinking of all the victims who are not remembered or commemorated in any way, such as the women or children,[4] it becomes clear that official monuments are further contributing to the division in the country. These monuments, that are mostly dedicated to men and military-related events, are often instrumentalized by local politicians without serving any reconciliation purposes or peace-building efforts.[5] In such a complex context, contemporary art can offer an alternative – a healing alternative that allows viewers and participants to actively remember and, in time, to overcome their traumas. In this region, it is mostly women artists who are navigating this healing process.

Aida Šehović began her installation project ŠTO TE NEMA (roughly translated as Where Have You Been? or Why Are You Gone?) in 2006, 11 years after the Srebrenica Genocide. The installation, which the artist describes on her website as a “participatory nomadic monument,”[6] has traveled to 15 different cities around the world. The project began with the artist’s desire to collect a fildžan (traditional Bosnian coffee cup without a handle) for each of the 8,372 victims of the genocide. The true number of victims is much higher, but this was the official figure given by the tribunal. The number continues to grow each time a new mass grave is discovered. After hearing from survivors that what they miss most is the company of their loved ones, Aida Šehović, with the help of members of the Women of Srebrenica Association, began asking the families of victims if they would like to donate a cup. In time, she managed to collect more than 9,000 cups from the families of victims and other people interested in the project. Every 11th of July, volunteers, together with local communities and the Bosnian diaspora, would help Aida organize the monument in a public square of a new town, preparing traditional coffee, filling up the cups and placing them next to each other. The monument is no longer traveling, having arrived at its final resting place, the Srebrenica Memorial Center.

Drinking coffee is a tradition shared by Bosnian families and communities. It is an opportunity to slow down, spend time together and share thoughts and news. Šehović, who was born in Banja Luka, had to flee her hometown in the early nineties together with her family, eventually settling in the United States after living as a refugee in Turkey and Germany. Drinking coffee was one of the few rituals that her family continued to practice uninterrupted by their flight and multiple relocations, it was something that connected them to their homeland. According to tradition, an extra cup of coffee was always prepared in case of an unexpected visitor.

Many of the mothers, daughters, or wives of the victims in Srebrenica never came to terms with the genocide – the remains of their loved ones were never found, so they never had the physical confirmation that their loved ones were truly dead. Unable to begin the healing process and move on, these women still live in a perpetual limbo of not knowing. Building the installation together with Šehović, pouring coffee into the cup of a loved one, and coming together with people who have experienced the same or similar trauma has served as a reminder that they are not alone and that others stand in solidarity with them.[7]

In a context where official, public commemorations are heavily instrumentalized, those most affected by the tragedies are often left out. Aida Šehović realized early on that the monument she wanted to create should not bear any symbols or explanatory texts. Initially dedicated to Bosnians and the women of Srebrenica, it evolved to be open to everyone, because genocide and war are crimes touch all humanity. The memorial became an act of coming together; drinking coffee and talking in an open, public space. Any passerby can join in, regardless of gender, age, or ethnicity. Several trained volunteers are available to answer questions and talk to people during the performance, explaining the history of Srebrenica, the war, and the genocide. At the end of the day, the cups are washed and put away. Nothing remains after the collective experience, only the memory.

ŠTO TE NEMA is a stark contrast to the typical official, state-approved monuments: it is neither patriarchal nor militant. It involves the community and addresses the general trauma, not just the trauma of one part of the population. Even if its starting point and core are the victims of the Srebrenica Genocide, the monument has grown to include many different people who have stories to tell or who want to actively memorialize their own experience of trauma. It has managed to universalize a pain shared by many people around the world and, in a way, to encourage the healing process for some. As sociologist Katherine Riessman observes, “telling stories about difficult times in our lives creates order and contains emotions, allowing a search for meaning and enabling connection with others (…) When biographical disruptions occur that rupture expectations for continuity, individuals make sense of events through storytelling.”[8]

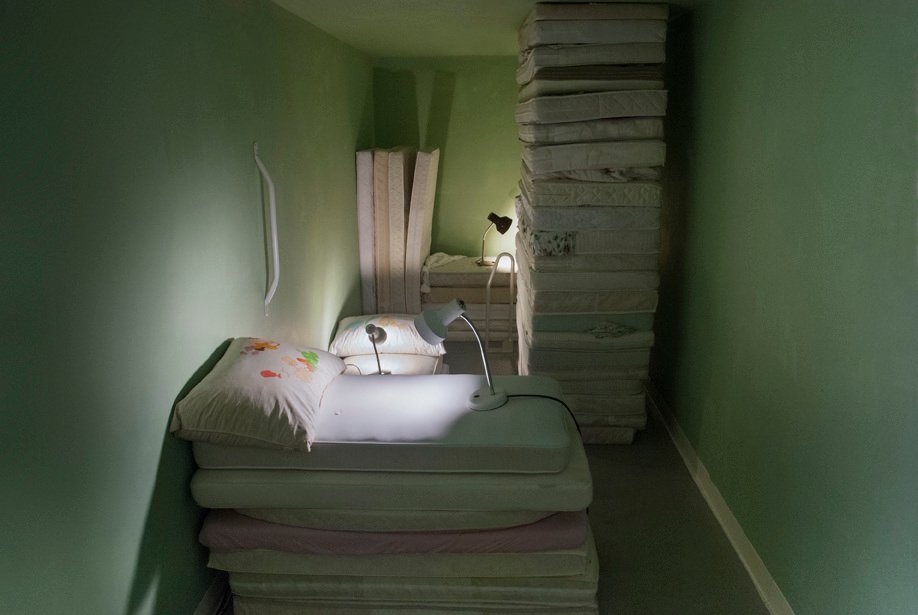

Highlighting the universality of pain and suffering is something that Ana Čvorović often does in her subtle and delicate artworks. The London-based artist was born in Sarajevo and experienced loss, displacement, and alienation in her youth, during the war. A central theme in her work is childhood, specifically the precariousness of children’s lives in war and crisis situations. During her talk for Kuma International School, she introduced us to Closeness, a 2016 installation which was placed in an abandoned bank vault, consisting of used mattresses piled on top of each other.

When I first saw the photos I was reminded of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Princess and the Pea, one of my favorite childhood fairy tales. On closer inspection, however, the installation quickly lost its dreamy, fantastical character: the mattresses were worn out and the artist had carefully painted the contours of sweat and other fluid stains on the pillows on top of them. Mobility aid bars and lamps were placed next to the mattresses, giving the narrow, labyrinthine space a claustrophobic feel reminiscent of overcrowded hospitals or underground bomb shelters. The installation was accompanied by a sound installation that through a constant static noise, created a sense of unease. The “closeness” was not the promised feeling of safety, but rather the lack of privacy and the imminent threat of something bad happening. The artist, who was forced to flee her home country with her parents when she was eight years old, had a little brother who suffered from cerebral palsy. She shared that they were forced to leave him in a hospital for children with special needs until they could return for him once they had a safe space. Because of the circumstances of the war, he became trapped there and died within a year. Two months after his death, the entire staff abandoned the hospital, leaving the disabled children alone for three whole days until the UN troops arrived. Looking at the installation and knowing this background story, one cannot help but feel a chill run down one’s spine and an immense sense of sadness and helplessness.

One of her more recent exhibitions, Borders Unfold, organized in 2019 at Pi Artworks in London, featured bold colors and curious, inviting shapes. The space was divided in two by a large red tarpaulin curtain that had many holes punched in it, reminiscent of the damaged facades of Sarajevan buildings. On closer inspection, the curious shapes turned out to be glass bowls filled with colorful children’s bathing costumes that the artist acquired from thrift stores during a residency in Utica, New York; a city with a large Bosnian diaspora. The installation suggested summer pastimes, the joys one would have as a child of swimming or playing in the sun on the beach or at a lake. Five rectangular metal shapes placed on the floor were holding up two metal rods each, with the glass bowls perched on their ends. The strange feeling of floating, of not being anywhere, interrupted the initial ease and lightness induced by the set-up. On the other side of the curtain, uncovered mattresses laid on the floor, each with a colorful bowl full of bathing suits. The scene initially felt like a summer camp dormitory, but the piece of tarpaulin on the wall, on which the artist had delicately painted a scene of destruction in a city with a mosque in the middle, shattered any illusions. A spectral soundscape enveloped the space with diffuse, non-human noises, making the whole experience feel like we were underwater.

Čvorović’s installations do not offer any relief from the pain of children being displaced and separated from their families around the world, because there probably isn’t any. But they do invite introspection and reflection on an issue that is so uncomfortable that it doesn’t get the public recognition it deserves. The artist succeeds in creating an immersive environment where awareness is raised for the stark contrasts between what childhood should be – a safe space where one can develop freely – and what it is in reality for many, especially during times of war and crisis – a scary, disruptive, and unstable experience.

While the suffering and pain of the war is still visible after 30 years, making one wonder what our contemporary situation will be in just as many years, with a destructive war menacing Europe right now, the fact that art can address these issues in a non-intrusive, emancipatory way is already a glimmer of hope. Understanding the importance of creating space and platforming the voices of all victims, and not just replicating propagandistic colonial, military, or other oppressor narratives, is already a step forward in understanding how to process and commemorate post-war realities.

[1] See: Human Rights Watch, Bosnia and Hercegovina, A Closed, Dark Place: Past and Present Human Rights Abuses in Foca, ed. Holly Cartner, Vol. 10m No. 6, July 1998, URL: https://www.hrw.org/legacy/reports98/foca/#_1_1

[2] Ibd.

[3] See: Dzana Brkanic and Lamija Grebo, Bosnia spends €2 Million on ‘divisive’ war memorials, 3.01.20220, URL: https://balkaninsight.com/2020/01/03/bosnia-spends-e2-million-on-divisive-war-memorials/

[4] There is one memorial of children killed during the siege of Sarajevo in the same city, whose concept and inauguration were heavily criticized by citizens and observers, see: Nedžad Novalić, Commemoration for killed children not focused on killed children, 7.06.2023, URL: https://nenasilje.org/en/commemoration-for-killed-children-not-focused-on-killed-children/

[5] See: Dzana Brkanic and Lamija Grebo, Bosnia spends €2 Million on ‘divisive’ war memorials, 3.01.20220, URL: https://balkaninsight.com/2020/01/03/bosnia-spends-e2-million-on-divisive-war-memorials/

[6] https://stotenema.com/2006-sarajevo

[7] Susan Snodgrass, ŠTO TE NEMA – A Living Monument: An Interview with Aida Šehović, 11.04.2021, URL: https://artmargins.com/sto-te-nema-a-living-monument-an-interview-with-aida-sehovic/

[8] Catherine Kohler Rissman, Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences, London, Sage Publications 2018, p. 24.

Additional bibliography:

Novalić, Nedžad, Commemoration for killed children not focused on killed children, 7.06.2023, URL: https://nenasilje.org/en/commemoration-for-killed-children-not-focused-on-killed-children/.