Joachim Aagaard Friis

At Tallinn Photomonth, photography becomes less about images and more about how we see, sense, and exist in a world saturated with them — from ecological materials to artificial consciousness and quiet public gestures.

Photography as a Living System

What does photography even mean in 2025? The screen and its image are now such a quotidian visual experience that it almost feels biological, it is ingrained in our nervous system and our bodies’ default coding. It is not quotidian in a romantic way though – in the sense of a stroll down a quiet street or a chat with a friend – but more in the way that our other bodily needs like hunger and hygiene present themselves. It is a visceral omnipresent part of our lives – something that has slipped from the area of “aesthetics” to something more deeply implied in the human experience. Therefore, it is maybe more important than ever to address the concept of photography through art.

It is clear from the beginning of my visit that Tallinn Photomonth takes on a similarly broad perspective on photography in its autumn biennial. It is about photography as a framework, a way of thinking and understanding our intensified world mediated by cameras, screens, and images more than about photography as a specific medium or method.

From Cardboard Boxes to Cyanobacteria: Material Ecologies of Image-Making

The first work I encounter is Andrey Bogush’ Rendering for 2 Monkeys Reading Love Letter to Barthes, in Box, with Light (After Brugel) (2025). It is a cardboard box hanging from the ceiling with round and triangular holes cut into it. Inside is a plastic candle and postcard stuck to one of the sides of the box. The postcard shows a painting of two monkeys, but it is not the famous one by Bruegel himself (Two Chained Monkeys, 1562). Bogush plays around with references of colonialism, materiality, and French Theory, but it’s done in a subtle and almost perfunctory fashion. As if to welcome the question “is that supposed to be photography?” head-on with an invitation inside a faux camera-obscura. This is an extreme example, but it points to the approach of the biennial as a whole: it thinks of photography as a mesh of questions, materialities, and societal issues.

Bogush’ work is part of the exhibition Just juuri nüüd nyt (something like “Just right now now” in English) – a collaboration between the Estonian Union of Photography Artists (FOKU) and the Finnish Association of Photographic Artists (VTL). A jury has chosen ten artists from the two unions out of more than 500 applicants. The result is a simmering show spreading over FOKU gallery and Hobusepea Gallery, both in the old town city center. The artists seem restless to break boundaries, curious to try out new combinations of mediums and sometimes, with more or less success, to provoke.

Karl Ketamo couldn’t be farther from Bogush in his practice, except maybe for the fact that they both seemingly have nothing to do with a traditional understanding of what photography is. Basing his works on found and recycled objects, his expression is colorful and quirky. Just behind Rendering for 2 Monkeys… stands Ketamo’s In No Time (2025), a found gasoline canister with other small trashy objects like stickers and rubber attached to it. It is all play and surface it seems, a plunge into the random – and wholesome – beauty of restricting oneself to working only with second-hand materials.

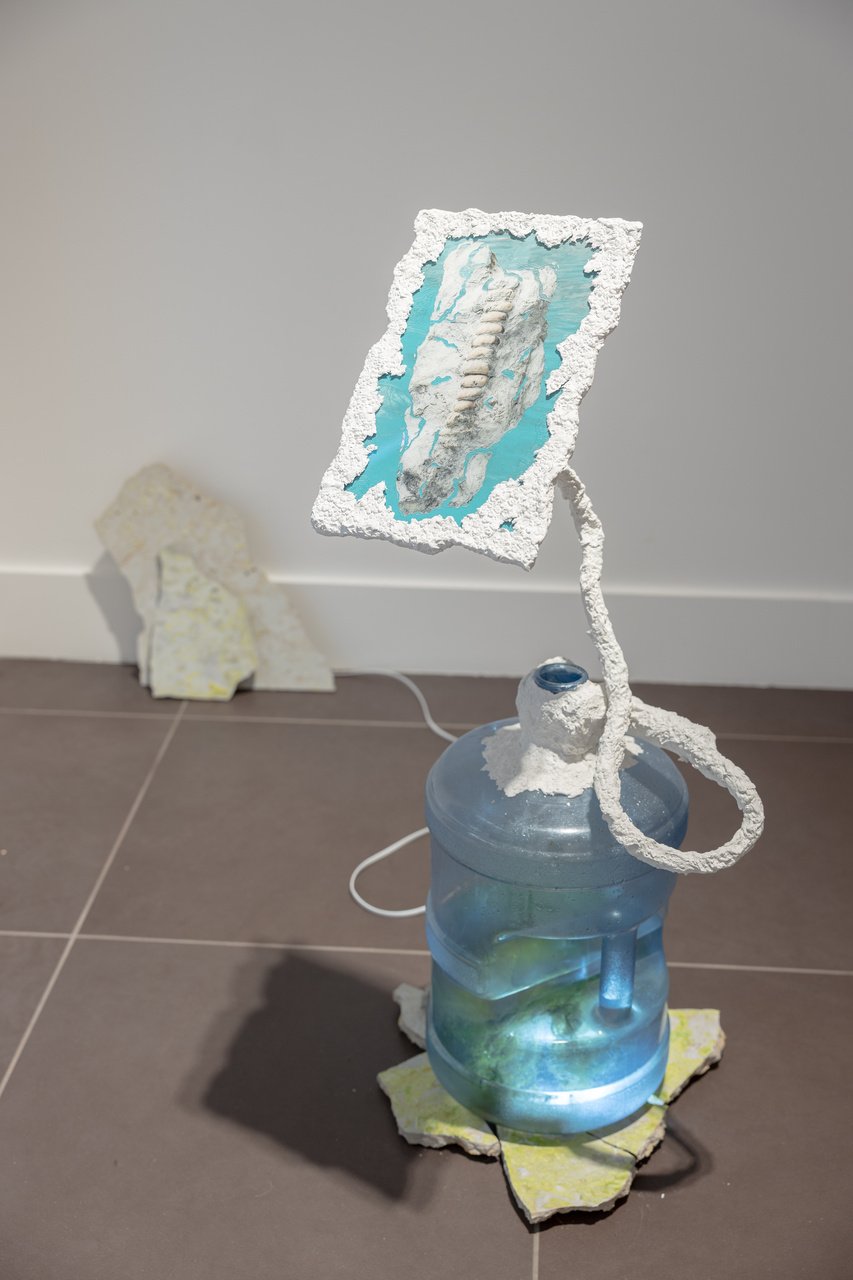

Kristina Öllek seems to be channeling some of the same second-hand aesthetics as Ketamo, but takes her point of departure from natural rather than urban materials. In her work, the geological and the biological merge: cyanobacteria, sea salt, limestone and bioplastic become photographic matter. In FOKU Gallery, Eutrophication, I See You (2024) and Loading Nutrients (2024), both from the series Converting Energy and Oxygen, examine the Baltic Sea as a living system – its toxic algal blooms, eutrophication, and shifting chemistry reflecting the wider ecological consequences of human activity.

Drawing on the beautiful Silurian limestone formations beneath Estonia’s coast – remnants of a tropical seabed formed 440 million years ago – Õllek folds deep time into her contemporary environmental observations. Her hybrid works – more sculptural than photographic at first glance – think with the sea: its sediments, histories, and speculative futures. Within the biennial, her practice stands as a reminder that photography is not only about light and surface but also about matter, metabolism, and the intertwined life of ecosystems.

When I look again at Bogush’ cardboard box, it strikes me that it also looks considerably second-hand, and Öllek’s plastic water tank has the same trashy aesthetic as Ketamo. As such, all three artists in this gallery are quite connected, at least visually, to a second-hand and ecological approach. From that perspective, the last artist in the FOKU gallery, Maria Kapajeva, is distinct from the rest. In her work, I Am Usually Woman (2013), her mother has quilted pillows and a blanket with numerous photos of women from Eastern Europe who are posing to find a man to marry in England, where the artist is based. This is the first instance of literal photos, resourced from the internet and printed on a quilt, connecting them to an intimate and domestic situation. The video, Test Shooting (2016), portrays a middle-aged British male actor posing for the artist while being given the instructions normally written for the aforementioned women trying to find a Western husband. Despite its quite literal, perhaps trite, turning on its head of gender roles, it is a simultaneously humorous and poignant piece. Watching the amateur actor pose almost naked and trying – horribly – at the feminine poses, put a smile on my face in an otherwise quite somber and serious show. At the same time, the artist succeeds in giving these women from the photos credit for their hard work in the struggle for a better life, while not neglecting a critique of the power structures that make such work necessary.

The Human, the Synthetic, and the Sea of Images

At Hobusepea there is a more speculative and fantastical vibe with Maija Tammi leading the way. Tammi’s installation turns the gaze inward – to the microcosm of human consciousness itself. Her work portrays human brain organoids aged between eight and twelve weeks: artificially grown, self-organizing three-dimensional tissues that resemble miniature brains. The images are UV-printed on glass and placed within deep frames painted with the blackest black, so that the organoids seem to float in a void – a playful nod to the Boltzmann brain theory, which imagines disembodied consciousness arising spontaneously from chaos. Accompanied by Tammi’s essay intertwining the cultural history of the brain with theoretical science and science fiction, the work brings a cerebral (no pun intended!) dimension to the show. It feels both eerie and poetic – a reflection on the boundaries between life, simulation, and image-making itself, and a reminder that the act of seeing is never purely optical but deeply entangled with imagination and cognition.

The speculative continues in Karel Koplimets’ video work Your Order Is on Its Way (2021), where in cool and dark tones, he constructs a near-familiar world in which automation quietly replaces human labour – a transition already underway, of course. The work doesn’t sensationalize this shift; instead, it lingers in its uneasy middle stage, where humans and machines still coexist but the balance is visibly tipping. This calm and realistic scenario is much more unsettling, because it shows us how the transition has already accelerated during the last 20 years without us really noticing the day-to-day changes.

photo: Joosep Kivimäe. Image courtesy of Tallinn Photomonth.

Untitled (2021), continues this inquiry through two lightboxes pierced with laser-cut openings, exposing their own internal mechanisms. The gesture of literally revealing what’s inside – both the machine and the medium – raises questions about our relationship to technology’s opacity: does exposure lead to understanding, or to new forms of anxiety? Instead of Bogush’ empty and trashy cardboard box, here the use of lightboxes, a format borrowed from advertising, turns the language of commercial display back on itself, implicating art’s own entanglement with visual consumption.

Koplimets work resonates with the broader tension between the organic and the artificial present in many of the biennial’s artists. Where Õllek materializes ecological systems and Tammi speculates on synthetic consciousness, Koplimets locates the human within an increasingly automated circuitry – neither fully in control nor entirely replaced. Together, their works sketch a portrait of photography and image culture in 2025 as a distributed, post-human field, where perception, labour, and matter are all being reprogrammed in real time.

Light, Reflection, and the Poetics of Rest

Apart from the group exhibition, two major solo exhibitions and a selection of site-specific urban interventions make up the main program of the biennial. Tanja Muravskaja has a long career behind her as a photographer focusing on societal and political issues in Estonia and beyond. Therefore, it is an interesting and welcome change to see her highly materialist and poetic unfoldings in Gardens: Tanja Muravskaja and Light installed in Saarinen House, a stone’s throw from FOKU Gallery. In the Gardens project, Muravskaja has dived deep into feelings of home and safety connected to the sea and its reflections and distortions through the photographic medium. All 14 works share the same big size (165×110 m) and almost the same abstract motif – a dark background with what seems like thousands of small blinking lights – or stars? It could literally be a satellite view of a big city on Earth or a starry sky on a clear night. But actually, it is close-up photos of the sea taken from Muravskaja’s childhood home Pärnu, altered so that the light is almost sucked out of them and only the reflections from the sun are visible.

The artworks in the series are extremely pleasant to look at – they exude a sense of calm, of immersion, a meditative space of quiet and peace. This is also Muravskaja’s intention, the exhibition text explains; to provide a fleeting space of quiet in a burning world. The works are even arranged as trees in a garden, standing with odd angles, so it is impossible to gaze at all of them at the same time, leading the viewers further into the exhibition and encouraging them to move around among them. The text further contextualizes a range of political meanings of the Baltic sea as a border and of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This is understandable, however, I think in this case it is important to value Gardens for what it provides: a step back from constant global anxiety and information overload to something simply beautiful, but also peaceful and safe. Moreover, I would have loved to see the exhibition text theorize the artworks in line with new materialism (and its many non-male authors) instead of only Gaston Bachelard (L’eau et les Rêves, 1942) and phenomenology. The highly abstract sea-motifs lead me to thinkers such as Astrida Neimanis (Bodies of Water: Posthuman Feminist Phenomenology, 2017) and her thoughts on bodies of water and the agential realism of Karen Barad (Meeting the Universe Halfway, 2007). This aspect is even accentuated in the fact that Muravskaja has printed all the photographs herself, choosing also texture, tone, and density, “so that the light does not remain a mere digital trace but becomes the materiality of breathing […] seeing paper as an embodied continuation of the image”, as the catalogue explains. The connection is almost too evident to be missed.

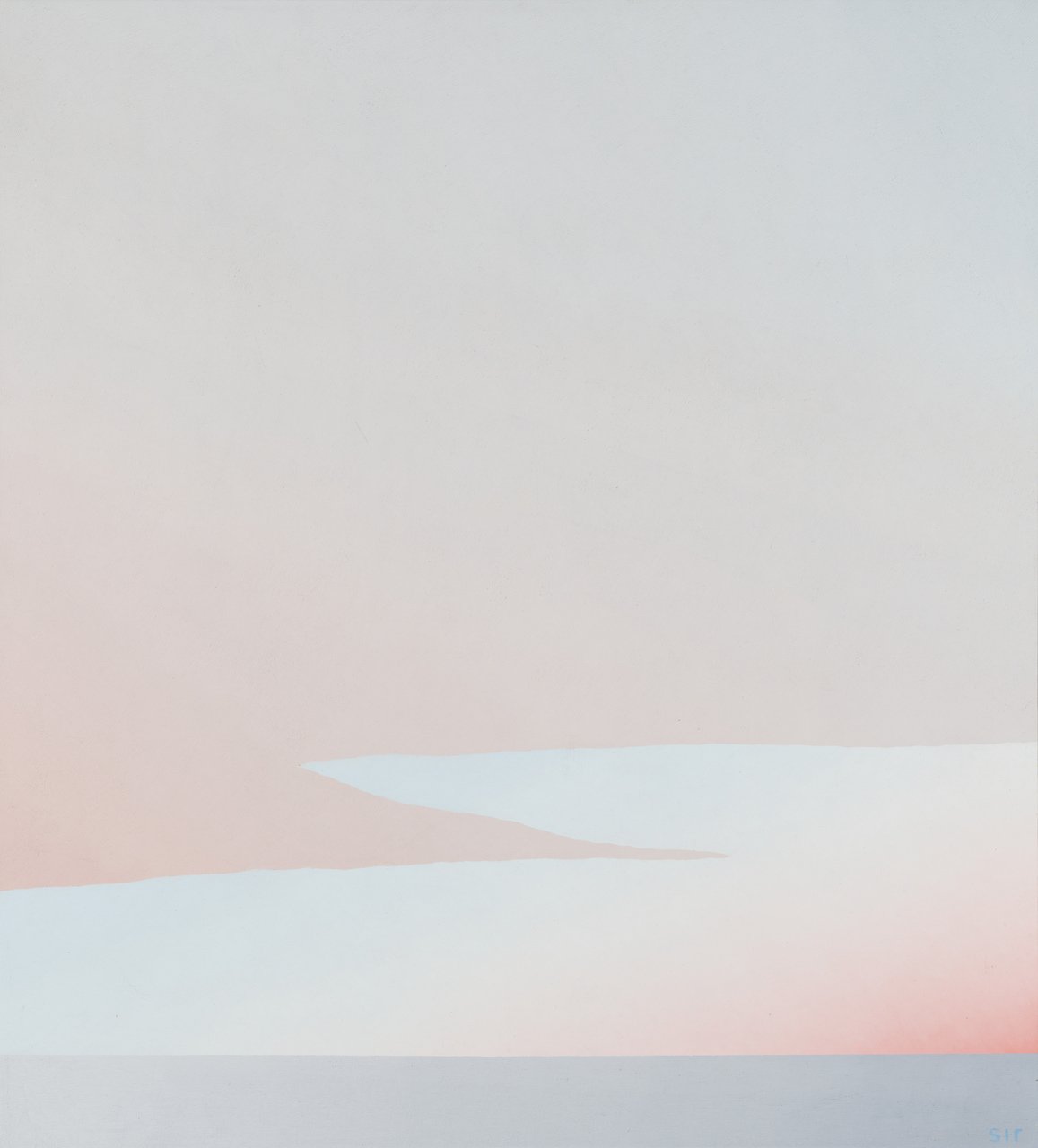

For the last exhibition, On Fragile Grounds. Sirje Runge and Light, I traverse the entire city bathed in sharp autumn sun. I end my journey by the harbor and the relatively new Kai Art Center which opened in 2019. The luminous exhibition hall fits perfectly for the legendary Estonian artist Sirje Runge, who has a career spanning 50 years. Again, there isn’t anything screaming “photography” here, mainly traditional abstract paintings fill the space. But the title leads the viewer a bit: it tells of an artist obsessed with luminosity: how light reflects paint and colors, how paintings change in different types of lighting and how to capture the essence of that slippery concept altogether. Since Runge hasn’t painted for the last 20 years, the exhibition consists mainly of her works from the 1970-1990s, and it is the first time so many of her works from that period are gathered. It is truly remarkable to follow how she has evolved her passion for light in different phases of her life: from almost completely dark works that play with subtle sparks to almost entirely white canvases with soft, almost imperceptible color contours.

Runge has an excellent intuition for color gradings and for illustrating how different nuances glide into one another on the canvas. Traversing her series on darkness, reflections in silver paint, combinations of two- and three-color gradings, the exhibition shows her deep commitment to the exploration of light and its relationship to color and mood. The hard sunshine from the overhead windows of Kai Art Center really helps set the atmosphere for Runge’s work and it is overall a pleasure to stroll around the space. Because of the natural lighting no angle hits quite the same, and the different perspectives of the viewer combined by the changing daylight makes it so that no experience of the works are the same, either – they change constantly with new reflections and abstract patterns emerging as time passes. One of the highlights is the series Landscape (1981-1994) which combines Runge’s love for light reflections with different moods of the Estonian landscape – both melancholic, peaceful, forceful, and tense.

Everyday Encounters and Minor Gestures of Public Space

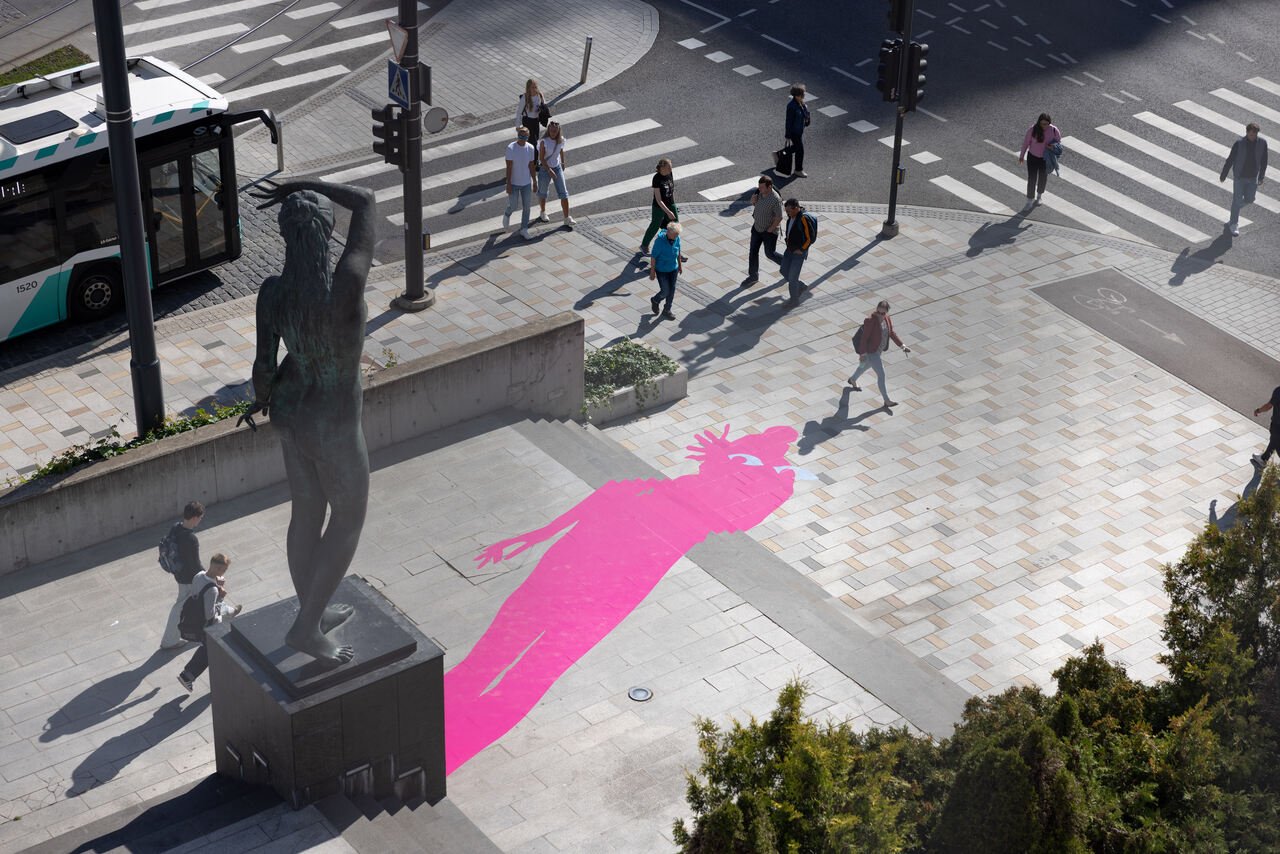

It is quite evident that Runge’s and Muravskaja’s exhibitions converse with each other on many levels, both regarding motifs and sentiments. On the other hand, the group exhibition echoes the public works, which I head back to the city center to check out before the sun sets. Curated by Kati Ots and Trine Stephensen, the show Shaping the Unclaimed intervenes in a highly commercial intersection among shopping centers and a construction ground where the former art academy once was. Now it will be rebuilt into (expensive) housing. Six artists intervene in this space, setting the stage for softer, more intimate and humorous interactions. The most immediately accessible work is Mare Tralle’s I see you! (2025), an installation interacting directly with the public sculpture Hämarik (Dusk) placed right outside Viru Keskus Department Store. The sculpture was installed by sculptor Mare Mikoff in 2005, mimicking a classical nude statue. However, the combination of the commercial setting (some people call the shopping center “dawn”, thus connecting the two), the size (five meters), and the nudity, has been a difficult cocktail for some. Here, the statue gets its own camp, big-eyed, neon pink shadow by Tralle, further building on its myth. It is a clever move, and to me, represents what good public and site-specific art can do: interact with existing surroundings, induce curiosity in passers-by, and generate new contextualizations (here, addressing awareness for (or lack thereof) the safety of sex and gender minorities in public).

Other works are less visible: Eva Stenram’s coquettish pin-up girls derived from their nude parts hide away on top of buildings blending into the urban backdrop and thus opposing Tralle’s approach. Mia Dudek’s liquidy large-scale photo of a private bathtub – the velvety textiles emerging from it paralleling the pastel discolorations on the walls – is hidden on an anonymous wall a bit further out of the center. Both artists present their work as something that you would stumble upon on your way from one thing to another, which bears a quality in and of itself, a quality of quotidian awareness in a stressful urban life. This could also be said of Elo Vahtrik’s The Bold and the Beautiful (2025), which has subtly exchanged a normal textile-fence around the construction site of the former art academy with a textile fence printed with colorful, kitsch photos. Or Sigrid Viir, who has decorated an underground pedestrian tunnel with 1950s-inspired domestic interior including colorful, flower-patterned curtains interspersed with photos of the artist quirkily puncturing the domestic idyll.

The biennial lacks a shared narrative – there is no text that encompasses all its exhibitions – but it seems there is a common wish among the artists to let small, everyday situations and minor gestures (The Minor Gesture, Erin Manning, 2016) matter; to create small magical moments of both peaceful introspection and unexpected encounters between strangers, human and material. In a time and place where larger political narratives seem to continually fail us, there is a certain momentary solace to find in these interventions. Going back to Andrey Bogush’ reference to Brugel’s painting of the two monkeys, I am reminded of Polish poet Wisława Szymborska’s ekphrastic poem about the same artwork (Two chained monkeys, 1957). Szymborska’s poem imagines the monkeys’ experience, chained to a windowsill overlooking a bustling city, to represent human suffering and our own enslavement through both ambition and oppressive systems. But Szymborska also emphasizes a new interpretation that focuses on the monkeys’ own resistance rather than just seeing them as symbols of human folly. As in the poem, the interpretations are many, but what I take with me from the biennial’s interventions is not primarily its commentary on photography in an expanded field – this field has become so expanded anyway that it can encompass much of the human condition. Nor is it a strong political stance which is not its main strategy either. Rather, it is the mundane and small-scale agency which seems like the most essential part of its contribution.

Exhibition Title: Tallinn Photomonth

Venue: Various

Place (Country/Location): Tallinn, Estonia

Dates: 05.09 – 31.10.2025