Ewa Borysiewicz, Vera Zalutskaya

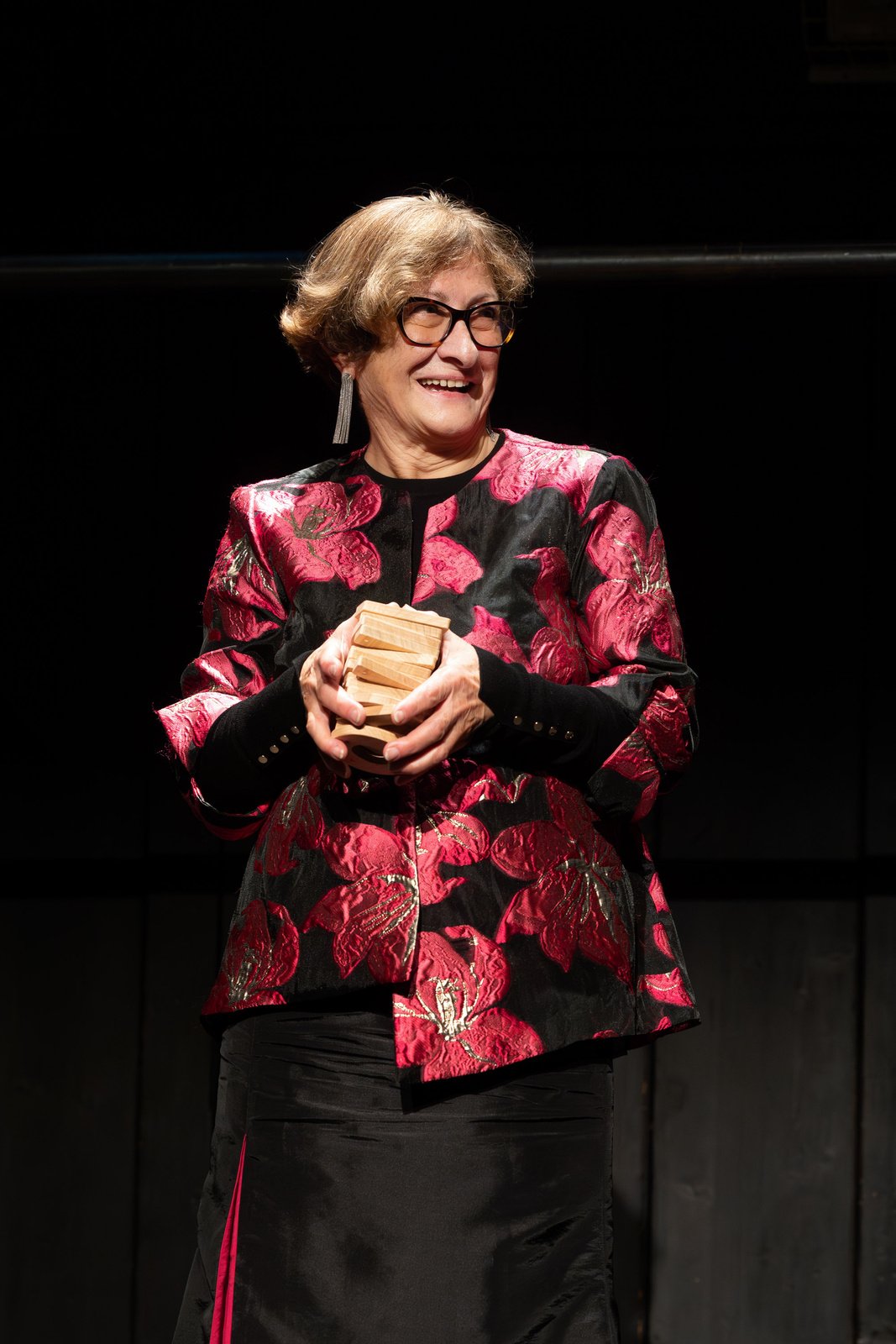

Ewa Borysiewicz: Hi Edit, it’s wonderful to see you again after our meeting in Ljubljana last November, when you received the Igor Zabel Award for Culture and Theory. To start our conversation, could you share what this prize means to you personally?

Edit András: I would say that the award is not just a recognition of one individual – it goes beyond that and serves as an acknowledgment of a whole generation of people like Igor Zabel, Piotr Piotrowski, Bojana Pejić. We were somehow squeezed in between two major periods: after Socialism and before the capitalist era. I would say that we were a lost generation when it comes to institutional power. None of us attained institutional power because we were too young for the gerontophile Socialist system. And after the political changes, we were too old for the new generation that was distrustful of its predecessors and was eager to take on the power. So our generation somehow was hemmed in between. But at the same time, we were not really interested in claiming power over institutions. Instead we were very enthusiastic and very much committed to the idea of finding a place for the region in art-theory, which was very much uncertain after the political changes. I think that we were a generation of “lonely wolves.” And to use this metaphor further, the Igor Zabel Award means that you are included in the pack of people for whom it was very important to see the big picture, from the moment on when we were liberated from the very closed society and we could breathe freely. Piotrowski, for example, wanted to create a theory on how to position East Central Europe in the newly extended world. Bojana organized Gender Check with the same aim from a specific aspect. And my obsession: how we can use Western critical theories for our experiences and for artworks produced in this region. So I’m simply very pleased to belong to this pack of wolves. It is absolutely wonderful that this activity, this lonely intellectual activity without institutional power, is now acknowledged.

Vera Zalutskaya: What you’re saying is very interesting because, from our generation’s perspective, it looks a bit different. I never thought of the people you mentioned as lonely wolves — I wouldn’t call you that — but rather as very focused on the “pack” dynamic. As you said, it was a whole team of close collaborators who, in a way, became institutions themselves. Now, everything feels much more spread out and divided.

I think many younger people working on Central and Eastern European issues — like we are at MOST — really miss that possibility to navigate within a broader context. We also miss the chance to network and have wider discussions about what we’re observing, what’s happening, and how to share know-how on managing our environments that are still very complicated.

EA: I get your point, and you are absolutely right in many ways. But in the last 20 years, new institutions have been established. It is easy to cross the borders and it is possible to study abroad, participate in special courses, workshops, etc. So there is an extremely diverse and rich system of research fellowship in operation that the current generation can use, enter. For us it was very much a personal, individual effort, and whoever wanted to undertake this effort, came together. This is how I see it.

Your question is a trigger for me to reflect on the issue of generations and to draw parallels with the next one. It seems to me that the generation which is active now already has a strong sense of the bigger picture and are more focused on the details – on micro philological, empirical research. I am now thinking of the criticism of Piotrowski’s In the Shadow of Yalta by younger scholars who point out the details he got wrong. And this is a legitimate criticism, don’t get me wrong, but in our time the big picture was more important; to speak about wider terrain not just about national art history, and to connect it, compare it with the wilder world. I just want to highlight that it’s a more zoomed-in perspective in contrast to the broader one my generation had, one that tried to encompass the whole region.

EB: I’m wondering whether you think a macro-level perspective is still possible today, especially given the current climate of information overload, fragmented discourse, and the prevailing emphasis on individual points of view. In this context, it seems increasingly difficult to find common ground or to develop a more universal perspective — whether as a thinker, art historian, writer, or in any other role.

EA: Our aim was not to create a universal version of history, but rather a communal, regional one. The goal was to situate the region in what was a newly opened world, to find a place for it. That was the main question. Where is the place of this region now when a bigger world opened up and became available to us? That was the question we raised from different angles. But the world changes drastically, at a very quick pace. We were very optimistic, enthusiastic, but the current state of affairs proves that our optimism was perhaps too great.

VZ: Returning to the idea of becoming institutions yourselves – you work as an academic, curator, theorist, and art historian. Is there one role that holds more significance for you, or do they influence each other in particular ways?

EA: When it comes to the category of curator, I would say that I sometimes, accidentally, fall into it. But whenever it happens, I always try to catch the theoretical aspect of it. Now, for example, I was invited to Trenčín, the European Culture Capital 2026, to be a co-curator of an exhibition with Ilona Németh. However, the situation is not so clear-cut as this role presents significant challenges. Beyond the tasks traditionally associated with curatorship, it also encompasses operational, bureaucratic, and political responsibilities which are quite alien to me. Regarding my role as a researcher, I started my career in this field in a research institute dealing with micro philology in Hungary, and then, after I spent some time in the US, I fell in love with new critical theory. Checking its applicability to the CEE context became my obsession for quite some time. If I were to define myself, I would say that I see myself as first, a theorising contemporary art historian, secondly a researcher, and curator – occasionally, accidentally.

VZ: I feel that today we are all, unfortunately, much more politicians than academics or researchers. I don’t mean creating political art or intentionally shaping it through political lenses. Rather, I am referring to how the art world operates within a capitalist framework, and how we are constantly required to tailor grant proposals, strategize about whom to persuade and how, just to gain the opportunity to organize projects or even to conduct research. It always seems to come down to these political considerations. As a result, the truly creative work — the deep reflective work — often becomes the last thing we have time for.

I think the difficulties you mention regarding curatorial work are becoming increasingly present across all fields. In fact, I feel that this political dynamic is now pervasive everywhere. Would you agree?

EA: Yes, absolutely, but I wasn’t given the opportunity to choose between the professional and political. I would say that my path has gradually led me toward a more radical stance. Especially taking into consideration those quite awful things which are happening in Hungary nowadays: those who are critical towards the regime are accused of threatening the country’s sovereignty. We live in an era when we are forced to be political. But in my opinion, we have to be political through our academic work as well, but to not politicize first or make our profession based on politics. So I still believe that it should work the other way around. I’m not eager to be considered as a political analyst or political scientist when I’m speaking about my professional field, which is culture. So I do not like to get out of my security zone as a public intellectual, because if I do so, then I am speaking from my private perspective, and I prefer to make public statements about what I am familiar with professionally. Privately we do not have any other option than to radicalize.

VZ: So what is political art for you? Do you think that art must be necessarily political?

EA: To answer you, I have to go way back in my life. I do not know how it works in other countries, but in Hungary, you cannot graduate as just an art historian, at least that was the case in my student life. You should have another major, like literature, aesthetics, sociology, history, or some language. And my university colleagues, who paired art history with aesthetics, for example, could never get past this concept of “pure art.” This feels very distant to me: my second major was history. At that time I thought “what a waste of time!,” but now I appreciate it very much, it allowed me to understand a lot of stuff retrospectively. I think that I simply practice an entirely different art history as compared to my colleagues who combined it with aesthetics and who would like to engage with “true” or “pure” art. I personally believe that all meaningful art has politics in it. I could say that for me, art becomes interesting when it has a social, political sensitivity, and which leaves a mark in the beholder’s mind, encourages to reflect on it, understand it, comment on it what is going on in our world.

EB: But it is also very shaky ground, as “political art” can easily slip into didacticism or even outright agitation.

EA: Yes, but still art can be political and simultaneously be nuanced, layered, interpreted in a multitude of ways. Like the often recalled example of the so-called revolutionary soviet avant-garde. If the political art loses this complex, layered nature, then it becomes a skeleton and gets didactic, as you put it: a message and nothing else. But at the same time I believe all art reflects on the society in which it was born and allows us to grasp some aspects of it that could not be comprehended without it, seen only through the lens of art. If art doesn’t carry politics, it is just pleasant decoration, a luxury commodity.

I see healing or comforting potential in artworks, the capacity to spark reflection in the viewer of art to be political as well. For example, many people have gathered around tranzit.hu, which has become a space of possibilities, with one of its main focuses offering the therapeutic qualities of art and the many ways it can be understood. Or take the positions presented at the Off-Biennale – which refuses to accept state funding. The bottom line is that art should not occupy an ivory tower, pretending that real life with all its dirt does not exist. And art’s emancipatory power is not to be disregarded: since it has that ability to represent those who cannot speak, or who do not have the power or the tools to convey their message, or cannot fight for themselves. There are many tendencies, definitions applied to art, but for me this social sensitivity is crucial.

VZ: To be honest, I feel that the agency of art is declining, so your perspective seems very heartening. What we are observing now in Poland, for example, is that the market is dictating the artworld’s rules, and almost everything must pass through this market-driven filter. It is very hard to see any emancipatory power in art today. On one hand, you know it will inevitably be consumed by the market machine. On the other – and this is the worst-case scenario – artists are forced to adjust simply in order to survive at the most basic level.

EA: It’s true that everything will be swallowed up by the art market sooner or later, but it’s a different thing to adjust to the situation. It’s like a game of cat and mouse, where the mouse is always one step ahead. Innovation, new ways in art is always possible. If we look back to art history, it was always possible to escape the power of the market, to figure something out. And then if it is swallowed, to find a new path. This was the case of performance, conceptual art, and land art; there is a force, but there is always another inner force to counter it. The only thing that is changing are the ways to counter this force, to resist it. The issue of the art market is very interesting. It’s also a very elaborate, clever trap. By the way, many people who are politically very critical of the regime or the institutional system, see no contradiction in cooperating with an institution in Budapest called HAB, Hungarian Art and Business, where art exhibitions serve as a pretext to empower a new elite. When speaking about the art market I always recall Meyer Schapiro. In the 1960s, he observed that the problem is not that some pieces are sold for millions of dollars on the market; the problem is that the art sold for such huge sums corrupts all art and everyone working in the field. In the time of Socialism, freedom meant to exhibit in galleries, free from state institutions. And even now some people are stuck to this idea that the art market equals freedom. But just as I said, it’s a trap, not yet realised, at least in Hungary.

VZ: The thing which is worrying me very much here in Poland is not only that institutions present the art offered – or verified – by the market, but that the market-oriented initiatives are heavily supported by governmental agencies, like the Ministry of Culture. It is becoming less and less possible to make a deep, comprehensive exhibition in institutions which are expected to present ideas. The only space for doing this is self organized spaces which are mostly relying on unpaid labour. And in effect, people are burning out very quickly, often before they are even able to produce a quality message or meaningful work, they simply give up.

EA: The situation in Hungary is very similar, and even could add that in Hungary it is even more complex, since the art institutions have been extremely politicized and used to fulfill both the right wing agendas and the market. The private galleries appear to artists as altruistic saviours in this context. All this happens at the same time when alternative galleries, critical art, or experimenters are not supported at all, neither through public nor private funds.

EB: I suppose many positions that achieve market success are presented as political; however, while they rightly critique one ideological system, they end up reinforcing another.

EA: I agree, this is precisely what is happening. I remember I was recently asked about feminist art in Hungary and I referred to it as “domesticated feminism” that has no critical edge, no intention of questioning the reigning political system within which it operates, and ends up being cute and harmless.

EB: It’s a very broad question, but I’ll ask it nevertheless: how would you describe the current situation of artists and art institutions in Hungary?

EA: It is a very broad question indeed, so I’m going to have to answer it broadly. The contemporary political landscape in Hungary is an effect of 14 years of the Orbán regime, and has involved a very slow and patient reconfiguration of the whole cultural sphere. At a certain point the far-right realized that political power is not enough and to have real power, they need cultural influence as well. This is an idea appropriated from leftist thinkers, Gramsci to be precise, who in the 1930s examined the idea of cultural hegemony. In essence, if you possess cultural hegemony, then you control the mind of the people. This opposes the orthodox Marxist stance which argues that the base is more important than the superstructure, which is just reflecting the base. Gramsci understood culture very broadly, so not only arts, but the way we communicate with one another, the way we think of ourselves. And this is Gramsci’s idea, a very powerful idea: what is happening in the minds could be equally or even more important than the state’s economic power. And what we see now, for example in Hungary, is that even though people are living day by day, they are still enthusiastic about the regime. How is it possible that, despite extremely high inflation, a collapsing healthcare system, and crumbling infrastructure, the regime still survives? It survives because the minds of the citizens have been occupied.

But as I said, this was a very slow and long process, with several stages. Firstly, the regime created parallel, far right equivalents of existing institutions. Every director of an institution founded on national ideals has been replaced and all current leaders are now loyal to the regime. Loyalty has become far more important than professional merit. For example, a new constitutional amendment states that one no longer needs a professional degree to be appointed as the director of an art museum. So it is very difficult for artists that cannot or would not like to make a career in the art market. They are struggling to survive, since the big public institutions give the floor to this traditional national art, a very conservative kind of 19th century craftsmanship, or apolitical, harmless or spectacular art.

EB: How do you personally cope with the situation?

EA: I’m very lucky not to be dependent on the system. So that is why I can allow myself to be critical about the cultural sphere. But where to find solace? The world we live in is very frightening. As I said, my other major was history. Sadly I see so many similarities with the 1930s, with fascism and its rhetorics. I have to find hope, I have to believe in a better future, I have a personal stake in this. But at this moment I see no hope, I’m still looking for it.

VZ: Solidarity may be a source of hope and solace, but it seems that solidarity in practice has become a domain for right wingers in the region, while the left tends lean into further compartmentalization.

EA: It’s a very good point and it’s sadly, absolutely true. In Hungary, the left was also sitting back and resting, taking it for granted that there was a predetermined way of doing things. We can observe similar strategies much more clearly in the American context nowadays, although the tendency is common everywhere. Trump could win because the Democrats somehow turned away from their original ethos, and by being involved with the Wall Street establishment, forgot whom they were supposed to represent. Hungary is almost a feudal vassal society at the moment: a very closed, claustrophobic system. And there are multiple kinds of leftist ideas or positions, but solidarity or connection between their representatives – just as you pointed out – does not exist. I think it’s a very dangerous situation we’re in. Because right wing alliances are forming not just within one country but internationally, as we have seen with Putin, Erdoğan, Trump, Fico and now the first round of the Romanian election with the victory of a far right politician.

VZ: In this context, could you tell us more about the Private Nationalism Project? How do you look back on it after several years?

EA: This was a project initiated by artist Rita Varga and was funded by the European Union. I was invited to be its theoretician. At that time, the conviction that nationalism is not something imposed on you from above but something that one internalized and participated in the dissemination of was very popular. My task was to write about this phenomenon. I elaborated on how nationalism existed even on a micro level, and that you couldn’t simply say, “I’m not responsible because it was enforced from above.” You had to face it, and in many ways, you had to identify with these elements. Even things like sports could serve as a tool for fostering national cohesion.

I’m glad you mentioned this project, because the ten years that passed since it took place make a huge difference. At that time, we were able to isolate this one problem. It seemed like a burning question, and we had the opportunity to analyze it in depth – to look at all the elements and symbols connected to it. How does it function? What are the key components – like borders, ethnicity, community? Who is excluded, and who is included? We examined it through many different segments. And if you were to ask me whether this is still relevant in the same way today, I would say no – we couldn’t organize this kind of project now. The reason is that today, you can’t isolate a single issue; there are too many overlapping crises. I believe this interconnectedness is now more important than ever. Even nationalism is no longer a standalone phenomenon, it is deeply connected to populism, to the fascist rhetoric, to how regimes address climate change, and to how economic interests are entangled with ecological crises. The trust in science is at its lowest point, there are growing inequalities. You can’t separate and neatly analyze just one segment anymore. New crises are constantly emerging, and each day we learn more about how they’re all connected. Somehow this net got surfaced.

I don’t want to fuel any conspiracy theories, but at the same time, I do believe that militarization and the rhetoric of sovereignty are all part of what you already mentioned – the capitalist system that post-socialist countries, especially Hungary, are eager to participate in. There’s a strong desire to catch up quickly with the very wealthy, well-positioned capitalist countries – or even with wealthy capitalist individuals.

We had this idea five years ago to continue Private Nationalism, and it reemerged as a project centered around the theme of universal hospitality, since we wanted to take this project to Vienna and realised that we cannot speak anymore about nationalism without migration. Then came the pandemic. So another element had to be added. We cannot speak about nationalism and migration without the pandemic and so on and so forth. So all these crises came together in the project we are preparing with Ilona Németh for Trenčín. We will see how we will succeed in addressing them all. The working title was originally Global Equality and Hospitality. Equality is important because hospitality implies a certain degree of hierarchy. But due to the fact that we did not have financing to involve artists from the Global South, we updated the title to Glocal Equality and Universal Hospitality (Invalidated ideas?). Our aim now is to address multiple crises of our troubled world through the lens of art. But in light of the political situation in Slovakia I cannot say if the project will materialise or not.

EB: Perhaps this is a good moment to ask about your definition of Central Eastern Europe.

EA: So from the very first moment I differentiated between post-socialist and post-soviet countries. During the Cold War, Eastern Europe was understood as a monolith. Then all those countries which were not part of the Soviet Union, wanted to differentiate themselves from this homogeneous conglomerate, so the Central Europe concept came along. And then after the political changes, the two terms were born: East Central Europe, or Central Eastern Europe, depending on which nominator has overriding importance. I myself would not define the term in geographical criteria. But basically, when I use this terminology, I speak about the post-socialist countries in Europe, but not the post-soviet. And the reason is that regardless of the vast amount of difference, we still do have lots in common. And this commonality for me is neither essentialist nor ethnic. It is more like we went through the same or very similar historical experience. And this historical experience is the most important feature for me, that’s something that never happened in Western Europe. In our region, the XX century was a period of running ahead into the future, of building utopias – Yugoslavia was the most representative example. Then most of the countries in the region turned back to the 19th century phase of nation-building period. In Hungary, for example, now we are experiencing a time travel back to the interwar period. It is demonstrated in front of the Parliament in Budapest. The square in front of the building now looks like as if in the 1940s, before the end of the Second World War. When you visit the capital you witness the reconstruction of that spectacle which was seen in the middle of the interwar period. And also the whole rhetoric around it, as if we jumped over and negated the experience of Socialism, which is erased from history and even inserted in the new constitution as an illegitimate period. This is a kind of time turbulence – going ahead, running back – it did not happen in Western Europe, or to my knowledge, in any other part of the world. The histories in the region are very different, but this is where the commonality lies: that this linear, smooth, not necessary progressive, but steady movement, is not present.

So my main thesis is that this turbulent history, resulting in these returns to previous periods or escapes towards the future, are the consequence of a deep memory of the many empires present in the region before Socialism was ever there. In case of Poland it would be the partitions and in Yugoslavia, being a part of the Ottoman Empire. The works and biography of Szabolcs KissPál are a good illustration of what I mean. As part of the Hungarian minority in Romania, he came to Hungary from Transylvania. And nowadays, paradoxically, many of the people who either came from Transylvania or remained there but obtained dual citizenship strongly support the regime in Hungary. KissPál as an artist, is very critical towards this situation. He says that the kind of ethnic nationalism currently promoted in the country did not previously exist in Transylvania, where Jews, Germans, Saxons, Romanians, and Hungarians used to live together. Nation-building in this part of Europe came relatively late. So, if you’re looking for common elements, this is one: nation-building here only began in the late 19th century, whereas countries like Spain, France, and other Western European nations had already established strong nation-states by then.

So I understand Central Eastern Europe definitely not as an essentialist category, but it helps to focus rather on a commonality in history due to the late nation building, due to a specific Imperial past, and due to experience of Socialism. Maybe we lived it in very different ways: we had goulash communism in Hungary, in Yugoslavia they had elements of capitalism, etc. And perhaps in art – like by Sanja Iveković or Zofia Kulik – we can identify another commonality. In different interviews, they all expressed that they were striving for a better form of socialism not to abolish it for the sake of capitalism; they genuinely believed in that utopian vision. They did not fight against it but they fought for it.

EB: And what about art history in the region? I was recently reading your text titled “What Does East-Central European Art History Want?”. It’s a great question in itself, but I wanted to ask you about your reservations towards Piotr Piortowski’s concept of horizontal art history, which you discuss in the text.

EA: So basically, as I mentioned before, finding a position for ourselves after the collapse of the whole Socialist system was the main question to work on for our generation of art historians and theoreticians. Another one was how to be an equal part of this bigger art history and not be absorbed by it as a derivative, submissive element, lower in the hierarchy.

But there’s another aspect of this situation: we had a very privileged position during the Cold War because we were the primary Other for the West. And that was a very good position because the region counted, the region represented art which was desired in the West, an art which had a stake, and was taken seriously by the state. The situation in the West was different; there the art was dominated by the market. So when looking East, they would see that artists could end up in prison for their art, that they are politically engaged, that they fight against the system. This view collapsed after the fall of the Berlin wall. The Interpol exhibition in Stockholm in 1996 was a symptomatic moment – it was the first real shock, a kind of shock therapy that showed us that we were not being treated equally. You probably recall Oleg Kulik’s Dog House work at this show. That was a clear message: yes, we could be integrated, but only as long as we played by the rules dictated by the West. If not, we were immediately pushed back into the stereotype of the brutal, primitive, impolite, and rude “Eastern Other.”

So from this old colonizing, universalizing, dominating European voice or position, we were not a distinct enough Other anymore. And at the same time, many other voices showed up on the scene, seeking to establish a position – and in this regard, Latin American and African art offer notable examples. African art, for instance, was strategically and effectively navigated into major platforms such as Documenta and the Venice Biennale by Okwui Enwezor. Latin America, on the other hand, approached this differently, even at the level of theoretical framing. There was a conscious decision to distance themselves from the term “postcolonial,” which was more commonly associated with regions like South Asia, particularly India, and the theoretical legacy of British colonialism. Instead, while still engaging with the broader concerns of postcolonial discourse, Latin American thinkers and artists began to articulate what they called the “decolonial option,” which marked a significant conceptual shift in positioning.

EB: So, what choices were genuinely available to Eastern and Central Europe in this context?

EA: One option was to assert our Europeanness – to claim that we are, and always have been, part of Europe. However, this often involved reproducing a submissive or secondary position within that framework. Alternatively, there was the risk of becoming entirely lost, overshadowed by the emergence of new “others” on the global stage. For them, we were not “other” enough to stand out. It was a fear of simply disappearing – of becoming invisible in the shifting geopolitical and cultural landscape.

My problem with Piotr’s idea was that for me, he was too much of a romantic. I once said to him that his ideas are wishful thinking, because somebody in power would not give it away voluntarily and to take the viewpoint of the margins as valid, “from where one can see better,” as he stated, and accept that the center is just another locality. And so this was my main hesitation regarding horizontal art history. Piotr died in a time where a different future was still conceivable. Now that it is clear that the power position remains intact, one can say that it has morphed into something even more aggressive. And there is not even an attempt to conceal it. Now we witness an absolutely straightforward display of power, presented directly and unapologetically. Trump embodied this dynamic with all its vulgarity; rude force without any effort to hide or camouflage it. But even though the postulates of horizontal art history will not be realized, it gave us a goal, a sense of orientation.

VZ: You were part of the Gender Check exhibition team, curated by Bojana Pejić. This project stands as a remarkable example of an attempt to position the region seriously and profoundly. It continues to resonate even today, in a time when most exhibitions are quickly forgotten after their opening. Of course, I am aware that the show faced criticism at the time. However, from today’s perspective, I see it as a truly unique exhibition, with a research methodology that was equally one-of-a-kind. Could you elaborate on this methodology and what Gender Check means to you personally?

EA: I’m truly pleased to hear that – very pleased. At the time Gender Check was organized, it faced harsh criticism, especially from within the region. The exhibition was criticized for certain omissions – someone pointed out that artist X or Z was left out. And yes, that may be true. But I would argue that it’s impossible to present a complete or total picture. I can accept those critiques but still, the exhibition was important in that it presented a different attitude – a different way of looking.

Of course, we are not homogeneous. But as we’ve been discussing, there is still a sense of commonality among us. And those subtle differences between us become visible precisely when we come together. Otherwise, when we’re isolated or viewed separately, those nuances often go unnoticed. So yes, it makes me genuinely happy to hear that the exhibition continues to resonate. In part, we’ve already touched on this – how our generation, myself included, wanted to grasp the broader picture. Gender Check represented that ambition, or at least symbolized it as an idea. Bringing all this work together was, at times, incredibly fruitful. That’s one aspect. The other is that the collaboration itself was truly a remarkable experience. One time, Georg Schöllhammer, who was involved in the project, had a very interesting observation following one of the discussions. In preparing the show, we – the curatorial advisors or researchers – would select the artists from each of our subsequent countries and present them to Bojana Pejić and to each other. We gave lectures about our countries’ challenges, explained the context for each work, etc. We spent many days sitting together, discussing ideas and various relationships within the project. Georg was amazed by the way we shared our concepts openly with one another. He pointed out that, unlike in certain contexts, such as some art biennials, where people guard their ideas closely, afraid someone might steal them, here it was completely different. He was genuinely shocked and impressed by the generosity; how we continuously contributed ideas to each other’s concepts without hesitation. This memory came back to me as you asked the question. That spirit of collaboration was, in fact, the method itself. It marked a significant difference – especially in how people from the region approached working together.

It is my belief that this collaboration comes not from Socialism, but rather from the unrealized Socialist ideas or Utopia, and working together, and not just that you, as an individual, would like to secure your career. This is something I definitely wanted to share with you because looking back now, it really was the defining characteristic of that coming together. And once again, while the exhibition received its share of criticism – and I could say the same about projects like horizontal art history or Piotr’s book, In the Shadow of Yalta – it was nonetheless necessary. It was essential, at least once, to bring all this artistic production together in one place. Only then can you return to the details, refine the narratives, and polish the specifics. But it had to begin somewhere, it needed a kind of kickoff. After that, you can start breaking it down, identifying individual contributions, adding missing names, and continuing to develop it further.

VZ: Looking back on Gender Check and its spirit of collaboration, how do you see the future of regional cooperation and collective work today? Do you think there is still space for such shared ambitions, or have the conditions changed too much?

EA: I still hope we’ll find ways to work together. There are certainly many reasons to be afraid – sometimes the situation feels so overwhelming that I just hope we’ll make it through. But despite everything, I continue to believe that collaboration is possible. And not just possible, but that it is very much necessary in order to survive.