“The human soul is international.”

(Bulletin international du surréalisme [Mezinárodní Buletin Surrealismu], Prague, April 1935)

Surrealism was a political movement of international reach and internationalist conviction. While it had its origins in art and literature, it far exceeded both. Surrealists declared reality to be insufficient. Their ambition was to radically alter society and reimagine life.

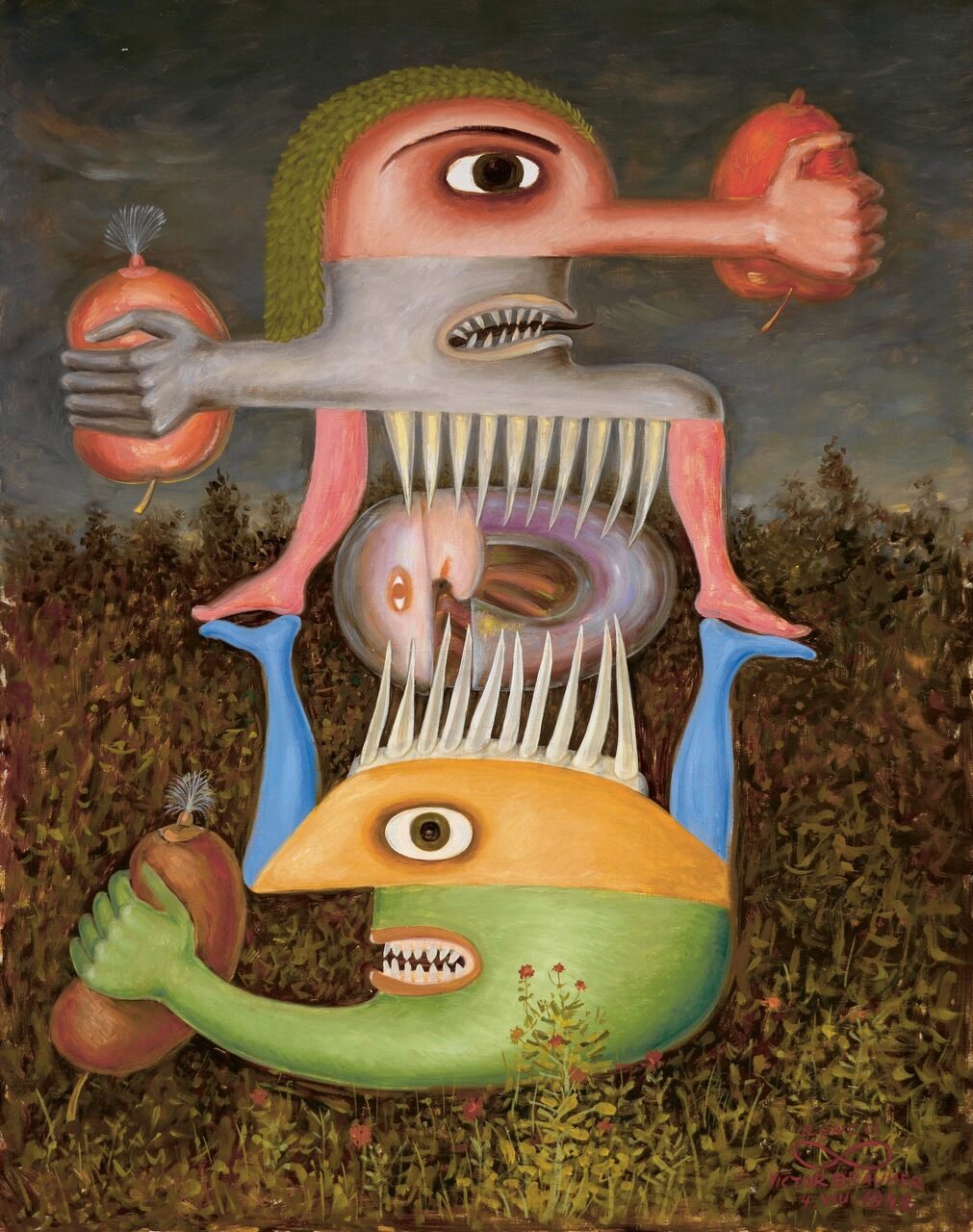

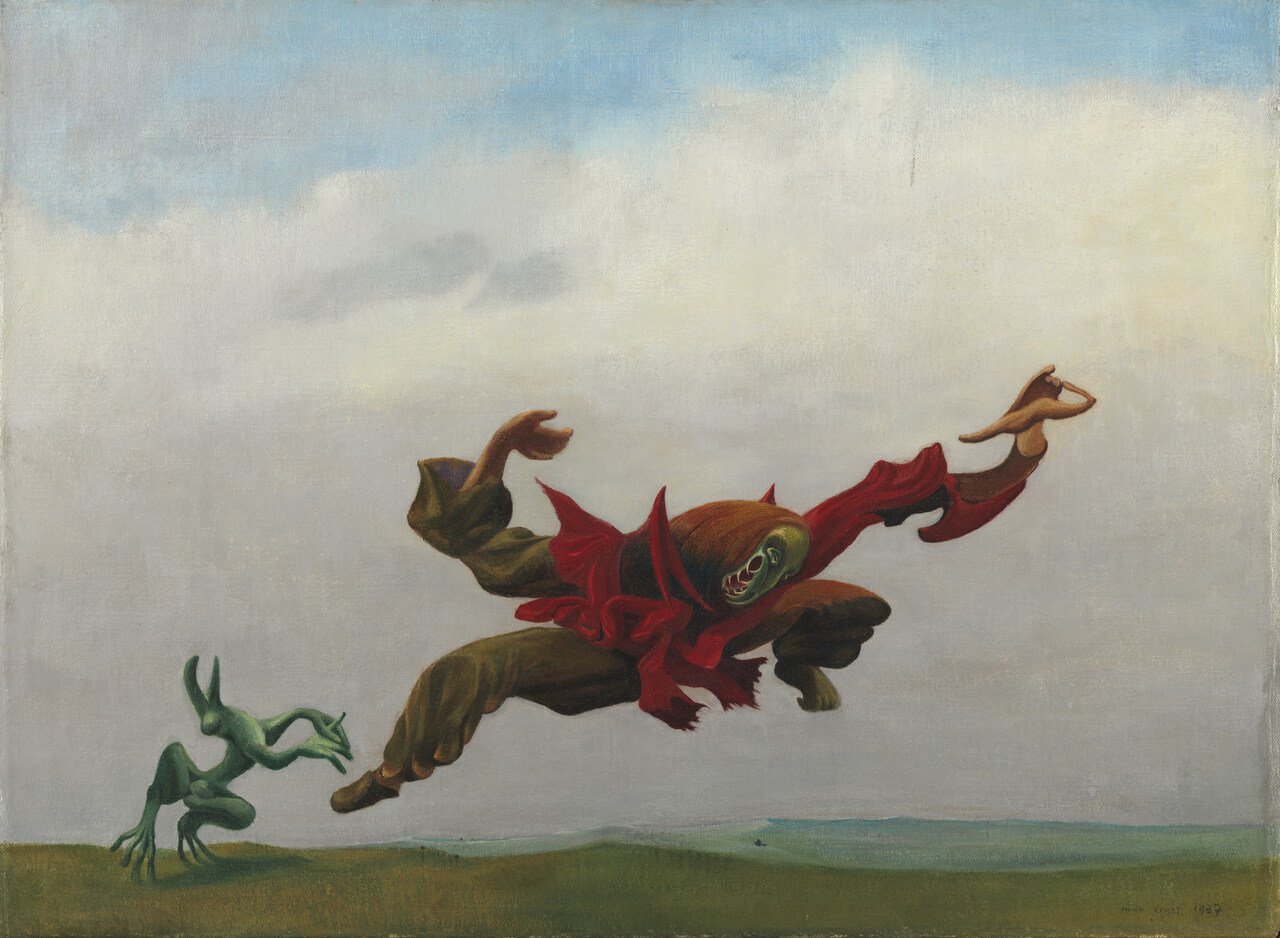

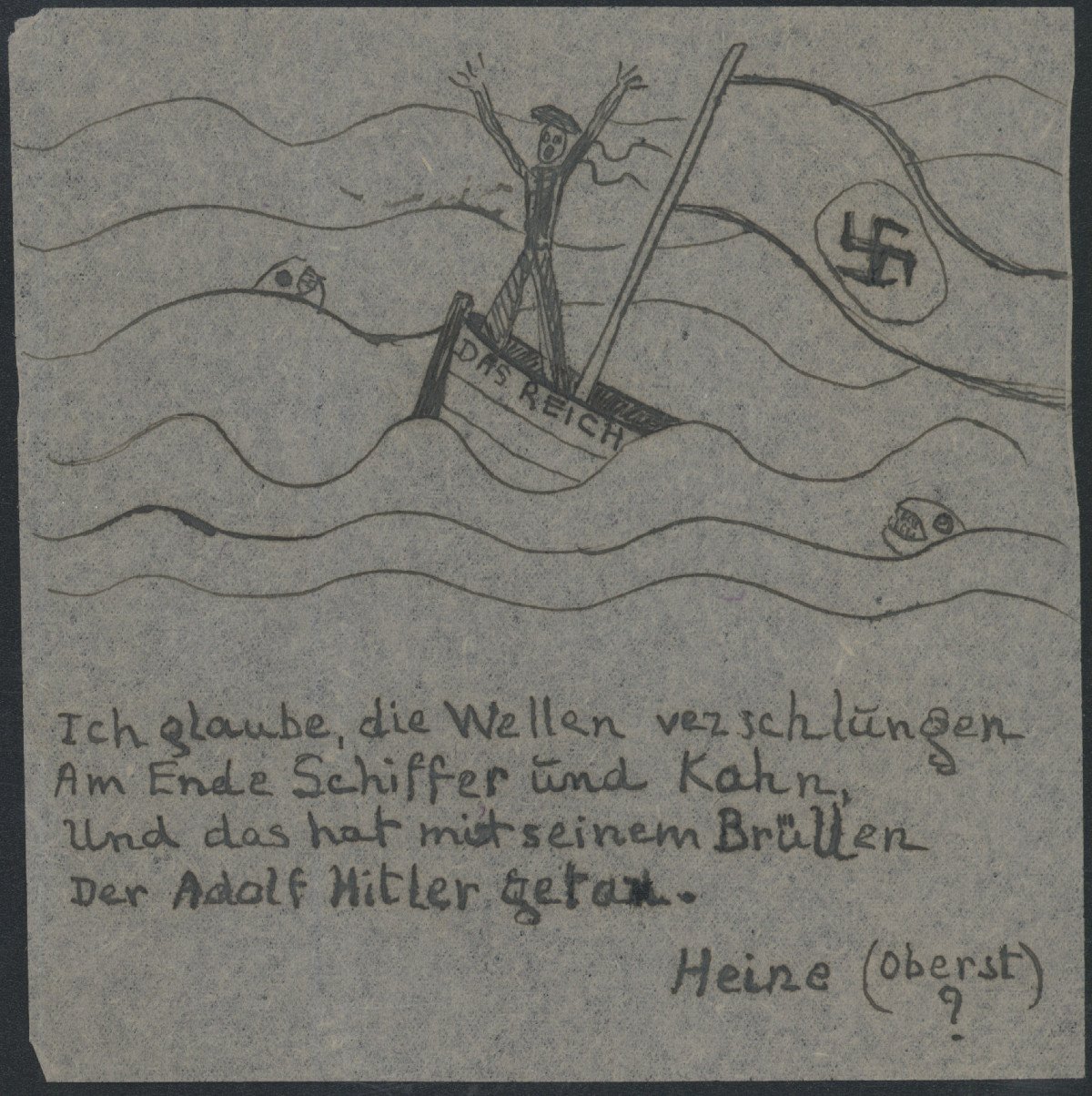

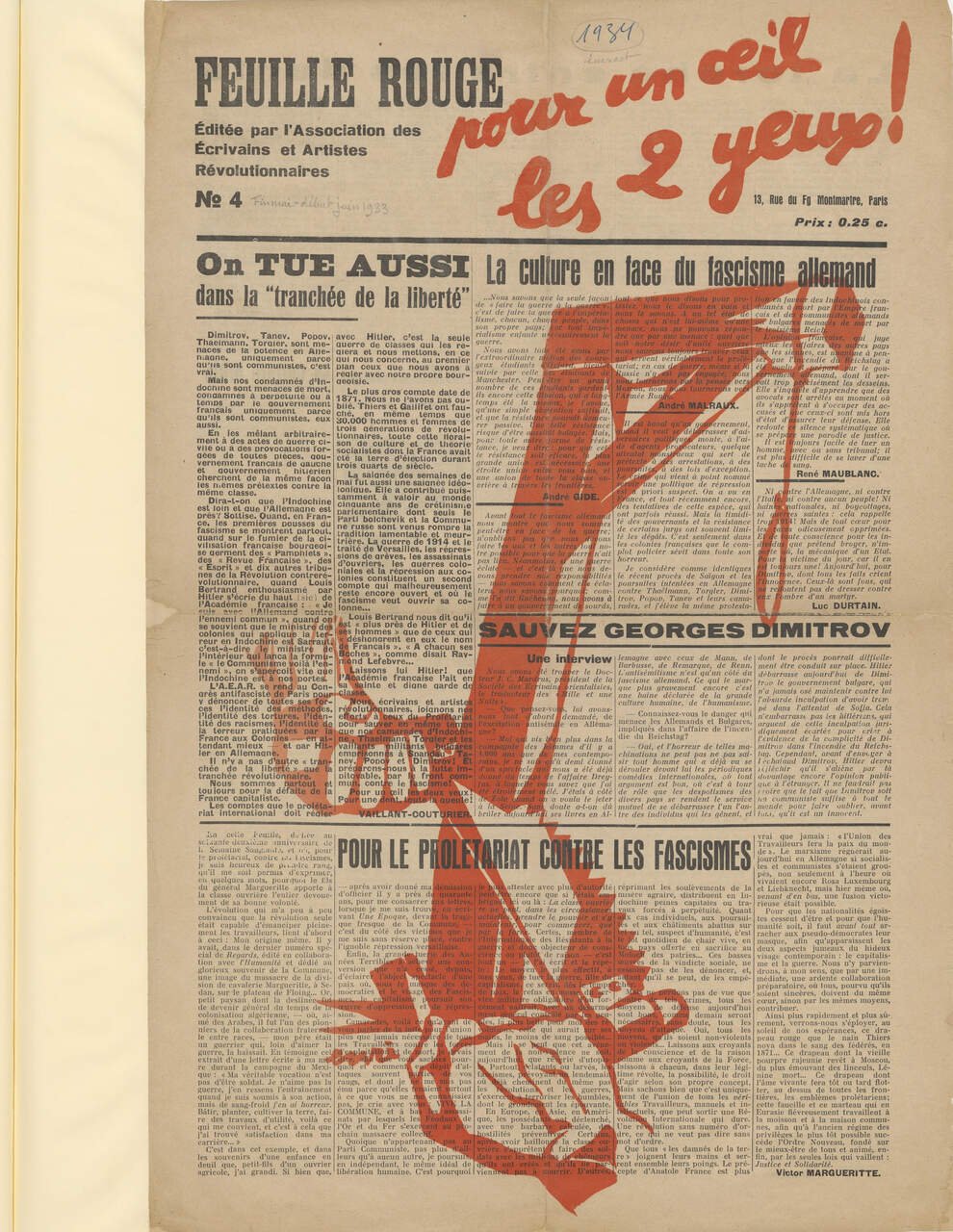

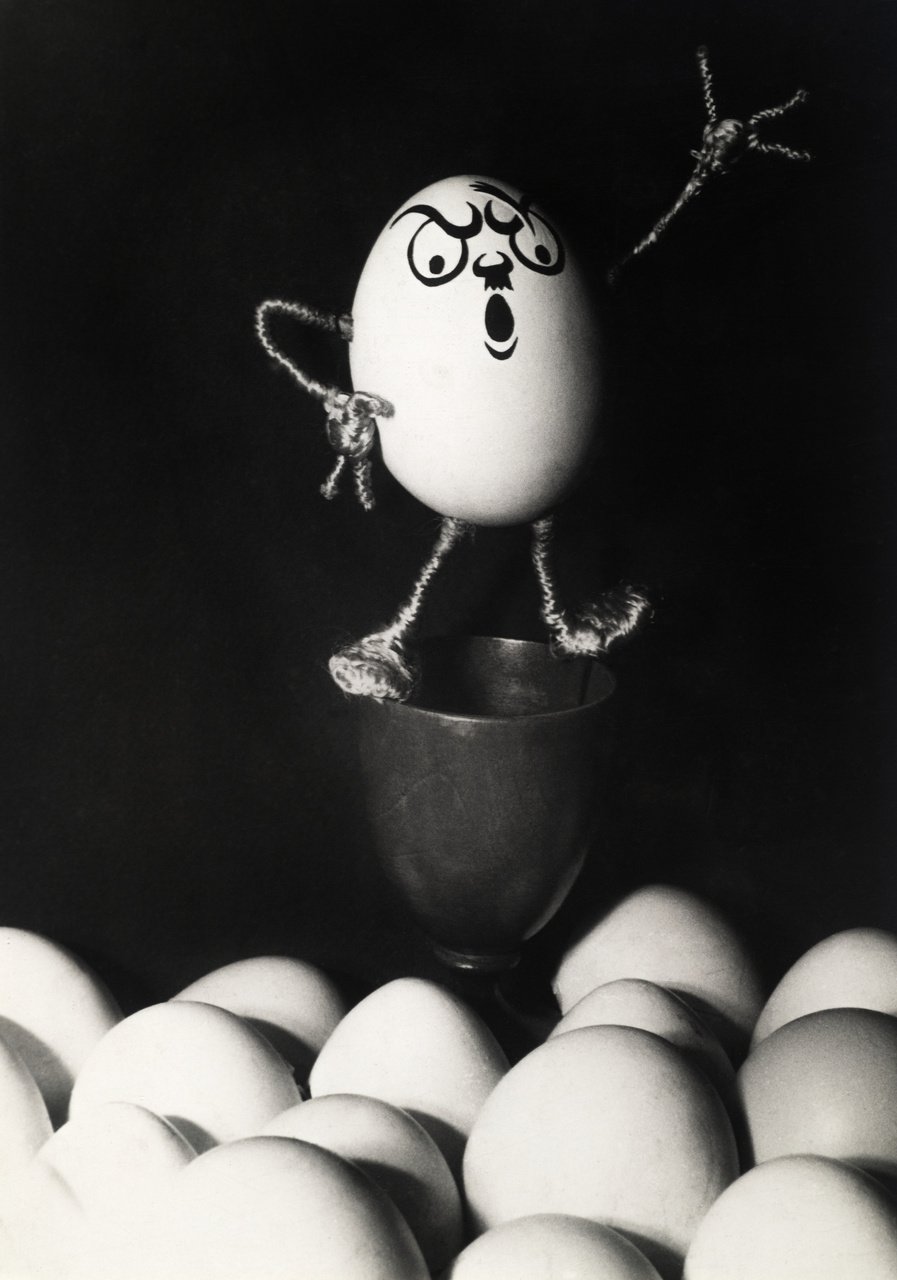

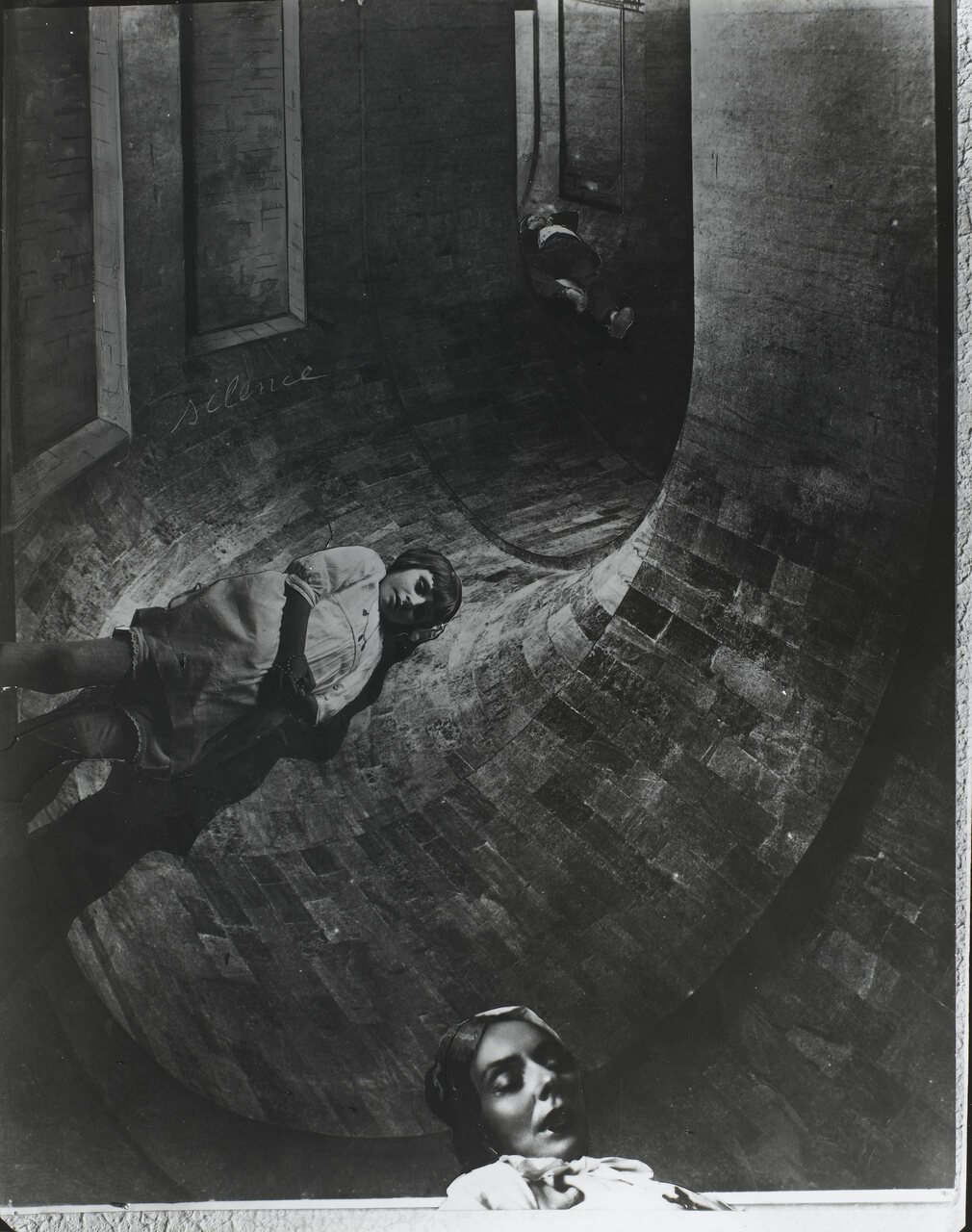

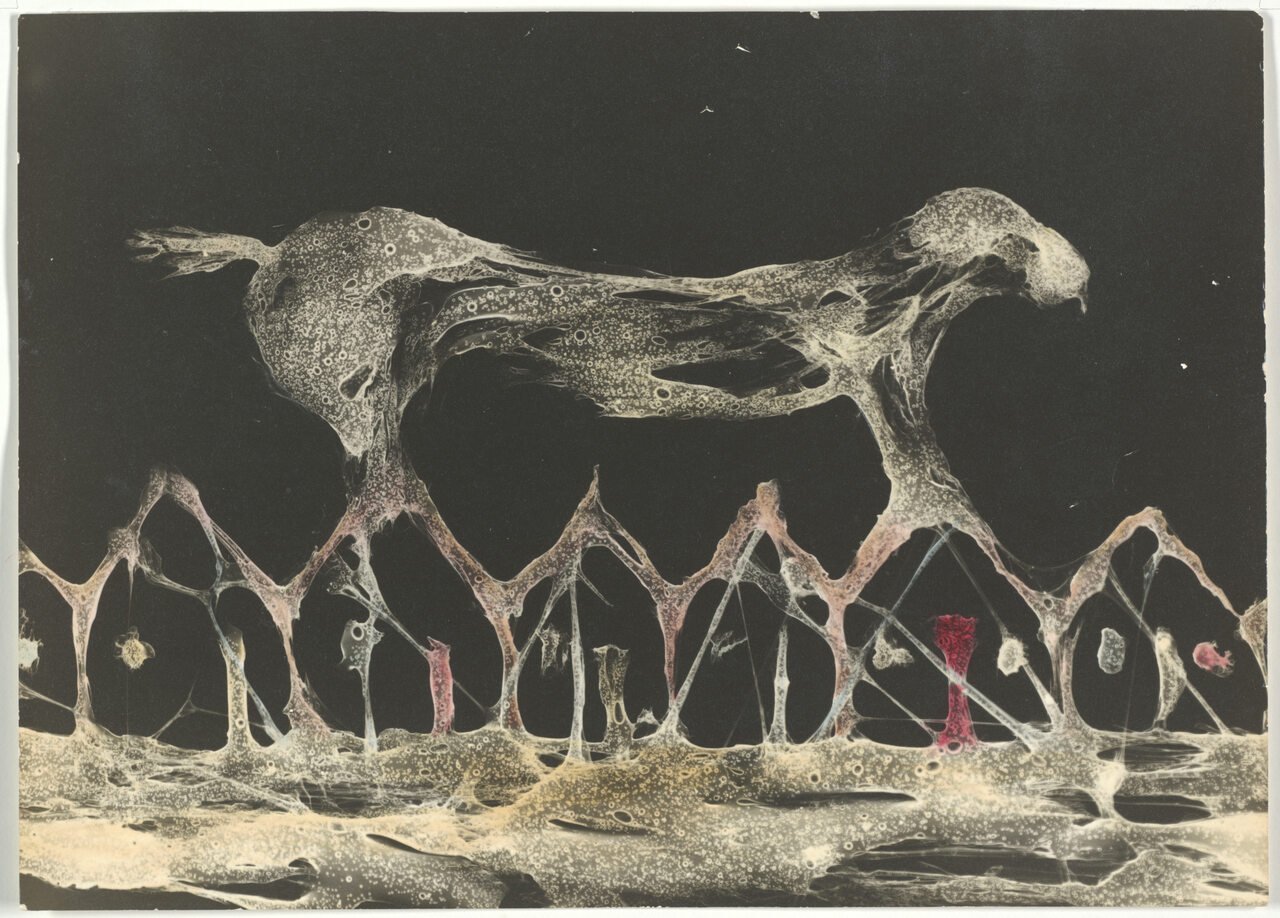

As early as the dawn of the movement in the 1920s, surrealists denounced the European colonialist project. They organized against fascists, fought in the Spanish Civil War, called on Wehrmacht soldiers to commit sabotage; were detained in camps and persecuted, escaped Europe, and died in war. They wrote poems, worked on paintings and collective drawings, took photographs, assembled collages, and organized exhibitions—all of which were aimed at disarticulating a supposedly rational language in a supposedly rational world. They refused to grant the “pathetic” imaginary world of daily politics access into their art.

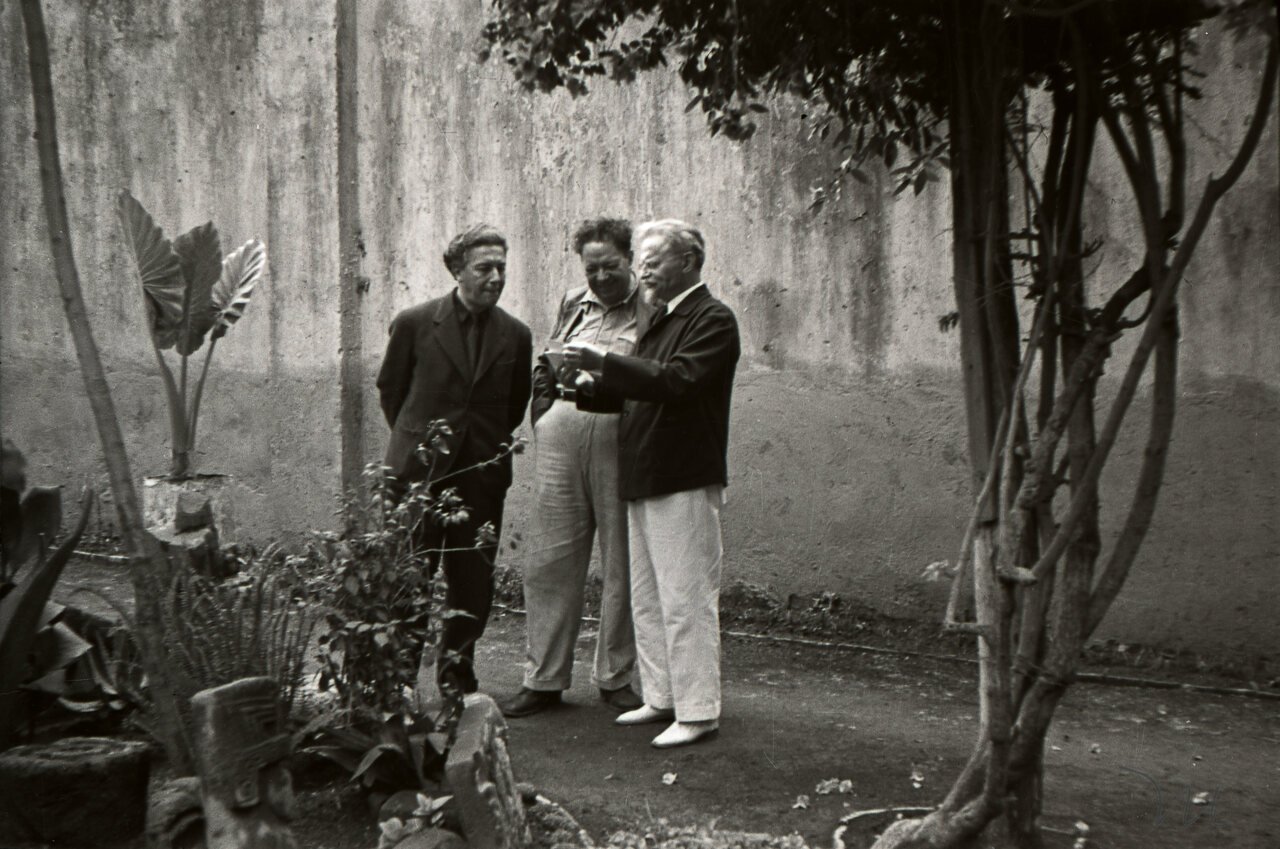

The government and occupation by fascist parties in Europe and throughout the world, as well as the World Wars and colonial wars, shaped Surrealism at the time of its emergence, and forced the lives of its protagonists into unpredictable trajectories. At the same time, these upheavals resulted in remarkable encounters and actions of international solidarity, whose red lines connecting links ran from Prague to Coyoacán in Mexico City, from Cairo to republican Spain, from Marseille to Fort-de-France on Martinique, from Puerto Rico and Paris to Chicago and back. Surrealist thinking and action, then as today, happened in various places simultaneously. Thus, instead of presenting a didactic, linear narrative, the exhibition is organized into several episodes, arranged like a map. The goal is to make Surrealism visible as the contentious, connected, and politicized movement its protagonists understood it to be.

© Lee Miller Archives, England 2024. All rights reserved. leemiller.co.uk.

Within their artistic work, the surrealists insisted on an absolute freedom that was to infect the rest of society. The surrealists’ understanding stood at odds with Fascist freedom: the freedom to command and obey. For the surrealists, emancipation meant a way of life whose rhythm was not that of wage labor and whose goals were larger than the glorious Nation and bottomless Profit. They bemoaned the stunted imagination of a society for which art and poetry had become eccentric activities. “If anyone comes to tell us that our present has other things on its mind than writing poetry, we’ll reply: ‘So do we!’,” wrote a member of La Main à plume, a group that fought in the Resistance in occupied Paris and secretly published volumes of poetry.

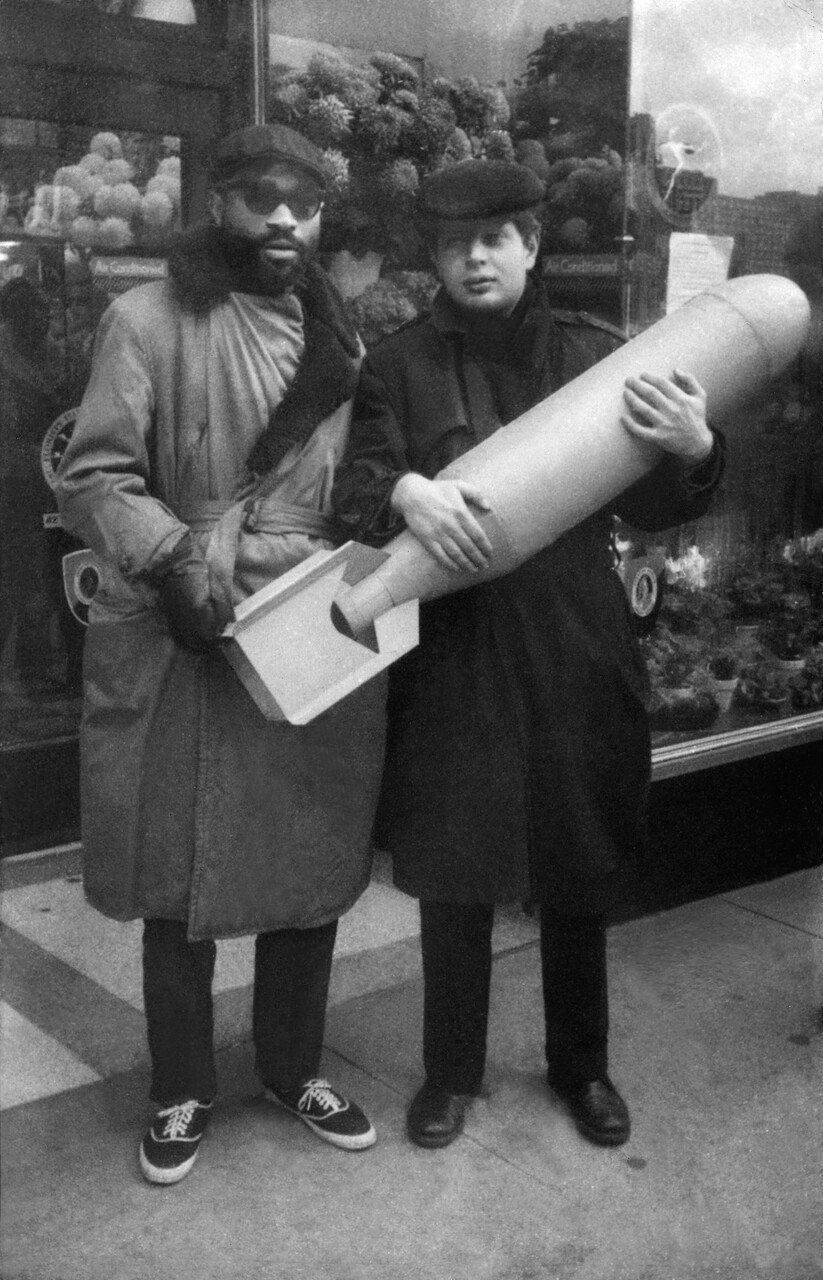

Not least because of this constitutive but open relationship between art and politics, later movements repeatedly invoked Surrealism: for example, as a method that can often be linked quite naturally to emancipatory goals, it was taken up during the 1968 protests and by representatives of the Black Liberation Movement. The exhibition at Lenbachhaus is conceived as a bundling of attempts to revise a still narrowly defined and politically trivialized Surrealist canon. Our goal is to arrive, together with our public, at new answers to the question, “What is Surrealism?”

Artists: Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Art & Liberté, Die Badewanne, Enrico Baj, Georges Bataille, Hans Bellmer, Erwin Blumenfeld, Victor Brauner, André Breton, Claude Cahun und Marcel Moore, Leonora Carrington, Aimé Césaire, Suzanne Césaire, Chicago Surrealists, Laura Corsiglia, Jayne Cortez, Roberto Crippa, Robert Desnos, Óscar Domínguez, Gianni Dova, Paul Éluard, Max Ernst, Erró, Esteban Francés, Eugenio Granell, Groupe Octobre, John Heartfield, Jindřich Heisler, Jacques Hérold (born Herold Blumer), Kati Horna, Pierre Jahan, Ted Joans, Germaine Krull, Erich Kahn, Marion Kalter, Wifredo Lam, Heinz Lohmar, Jean-Jacques Lebel, Dyno Lowenstein, Dora Maar, René Magritte, La Main à plume, André Masson, Roberto Matta, China Miéville, Lee Miller, Joan Miró, Amy Nimr, Wolfgang Paalen, Ronald Penrose, Pablo Picasso, Antonio Recalcati, Ré Soupault, Jindřich Štyrský, Yves Tanguy, Karel Teige, Toyen, Raoul Ubac, Remedios Varo, Wols

Exhibition Title: But to Live Here? No Thanks: Surrealism and Anti-fascism.

Curated by: Stephanie Weber, Adrian Djukić, Karin Althaus

Venue: Lenbachhaus

Place (Country/Location): Munich, Germany

Dates: 15.10.2024-30.03.2025

Photos: All images courtesy of Lenbachhaus, Munich.