Warren Neidich in Conversation with Józefina Chętko

Józefina Chętko: The Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art (SFSIA) recently inaugurated its fourteenth edition in Paris. Before we delve into this year’s program, I’d like to reflect on the institute’s origins and philosophical underpinnings. You founded SFSIA in 2015, is that correct? Over the years, it has evolved into a vital platform for interrogating the intersections of artistic practice, philosophy, and cognitive capitalism. Could you elaborate on the foundational ethos of SFSIA?

Warren Neidich: I began the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art in 2015. I asked the poet and art critic Barry Schwabsky to assist me in getting the program off the ground. It emerged out of our concurrent interest in art, poetry, philosophy, and the brain.

To answer the first part of your question, I would like to define terms before proceeding. At SFSIA, we believe that art comes before philosophy – not the other way around. Art is a generator of philosophy. Artistic production estranges, defamiliarizes, and refunctions the social, political, technical, and cultural milieu to such an extent that it requires philosophy, as well as other fields, to retool itself and weave together new infrastructures of meaning. The new information and its relations promote novel systems of knowledge. Sometimes, the result is so radical that it disrupts fundamental understandings and necessitates new lexicons and syntaxes to construct these systems of truths and beliefs, ultimately creating new systems of wisdom.

As Viktor Shklovsky famously stated in his Art as Technique (1917), “we need to make the stone stony”– extending the time of perception to draw attention to what has become overly familiar and therefore invisible, more visible. At SFSIA, we are not opposed to fields of production that translate or use raw philosophy as a guide to create artworks, as was common in the early days of conceptual art. However, we encourage arts’ unique capacity to generate new ways of thinking and doing.

JC: You mentioned the brain as a key interest that informed SFSIA. Could you expand on how this idea frames your approach to art and philosophy?

WN: Certainly. The brain I refer to here is not the “meaty,” crystalized brain, incarcerated by the bony skull and subject to brain scans, quantitative analysis, social engineering, or subjugation. Instead, it is a situated, cosmic brain – a plastic brain capable of change. It exists both as an intracranial condition and as well as an entity entangled with an extracranial counterpart: the social, political, cultural, planetary, multispecies and technological relations with which it interacts in real time and across generations.

This distinction is crucial to our approach. It aligns with our commitment to an epistemologically diverse, planetary perspective on art and philosophy, which we encapsulate in the term activist neuroaesthetics. Neuroaesthetics was the term I coined in 1996 for a series of lectures I performed at the School of Visual Arts entitled Neuroaesthetics, in the masters class of Charles Traub, who had invited me. The term neuroaesthetics was then usurped by the neuroscience community for their deterministic and reductive enterprise, which I totally rejected. To separate myself from this enterprise I altered the term in 2019 to activist neuroaesthetics. At SFSIA, activist neuroaesthetics is grounded in transversality, transindividuation, and planetarity as a mode of creation and resistance.

JC: What experiences and projects led to the founding of SFSIA, and how did they shape its mission and curriculum?

WN: SFSIA did not emerge out of thin air. It grew from nearly two decades of work organizing conferences, publishing, and engaging with interdisciplinary research. The first major milestone was the creation of the Journal of Neuroaesthetics in 1995 on my website, Artbrain.org, which later informed the exhibition Conceptual Art as a Neurobiological Praxis (1999) at Thread Waxing Space. At Goldsmiths College, where I was a tutor from 2004-2008, I collaborated with Charlie Gere to organize a class called Neuroaesthetics in May 2005, which included disciplinary fields like biopolitics, art praxis, and DJ culture and sampling.

In 2008, I co-organized the conference Trans-Thinking the City: Architecture of Mind at TU Delft, alongside architect Deborah Hauptmann. This was a turning point for me, as it brought together thinkers like Paolo Virno, Yann Moulier-Boutang, and Maurizio Lazzarato, whose insights into cognitive capitalism expanded my own research on the brain’s role in mental labor. Their influence was central to Cognitive Architecture: From Biopolitics to Noo-Politics (2010), a book I co-authored with Hauptmann, which explored how cognitive capitalism reshapes labor and knowledge production especially as it was reflected in architecture and designed space.

Building on these ideas, I organized a series of symposiums titled The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism (Parts 1, 2, and 3), held at institutions like CalArts, the ICI Berlin, and Goldsmiths. These events, accompanied by publications through Archive Books, solidified the theoretical foundations of what would become the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art. In essence, the institute formalized years of interdisciplinary engagement, creating a platform to explore how art, philosophy, and cognitive capitalism intersect.

JC: What motivated you to start a school like SFSIA, and how does its curriculum address contemporary challenges in art and academia?

WN: Three primary motivations drove me to establish SFSIA. Firstly, I observed that art schools were increasingly turning their backs on teaching critical theory and philosophy, reflecting a broader trend in posthumanism to de-emphasize the word in favor of the image or object. Secondly, one of the reasons for its decreasing importance, the theoretical frameworks being taught were often outdated, relying on postmodernist ideas that failed to address contemporary planetary and intersectional perspectives.

Thirdly, I felt that the art world was largely unaware of cognitive capitalism – a theoretical framework I saw as crucial to understanding the sociopolitical conditions of mental labor in the face of 21st century digitality. At SFSIA, we positioned cognitive capitalism as central to the curriculum, integrating it with discussions of neural materialism, sociogenesis (drawing on the work of Frantz Fanon, Sylvia Wynter, Lambros Malefouris, and Jean-Pierre Changeux), and social justice.

In cognitive capitalism, the brain and mind are the new factories of the 21st century and artists, as cognitariats, labor in the production of knowledge and data. This shift requires a rethinking of artistic practice as a means towards an emancipatory ethics of neural modulation as a form of resistance to despotic digitality and emergent forms of neural capitalism. Neural materialism emphasizes how objects, the performances they are engaged with, the contingent networks which result, and their interactions with sensory and cognitive systems, shape material changes in the brain. For artists, this is both a theoretical and political issue – one that demands new lexicons and practices to navigate and resist.

Last year, at the Maison Suger and the Fondation Maison des Sciences de l’Homme (FMSH) in Paris, we explored The Brain Without Organs: Planetarity, Plasticity, and Eco-Cosmotechnics, continuing our commitment to rethinking art, philosophy, the brain, and consciousness within an eco-planetary framework.

JC: Cognitive capitalism has been a recurring theme in SFSIA’s curriculum since its inception. With contributors such as Yann Moulier Boutang, Franco Berardi, Maurizio Lazzarato, and others, examining the rise of the knowledge economy and the performative and immaterial labor with which it is intertwined.

How do you see this framework reshaping contemporary artistic practices? Additionally, what role does SFSIA play in preparing artists and theorists to critically engage with these shifting economic and cultural paradigms?

WN: One of the important purposes of Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art was to make artists and their communities aware of cognitive capitalism as a means to create artistic streams of resistance against the suffocating power of digitality. It’s important to understand the historical roots of cognitive capitalism, which evolved out of workerism and post-workerism in the late 1960s and 1970s, during what has been described as a crisis in the phenomenological landscape of the worker. This was a moment when labor expanded to include life itself – a shift marked by the transition of industrial factories, like Fiat (FIAT), from analog to cybernetic inflected systems. In this shift, labor was increasingly deskilled, with a deliberate emphasis on reducing the need for specialized workers to suppress wages. Today we are witnessing a similar phenomenon with technologies like ChatGPT, which contribute to the deskilling of neural, cognitive, mental, and creative labor.

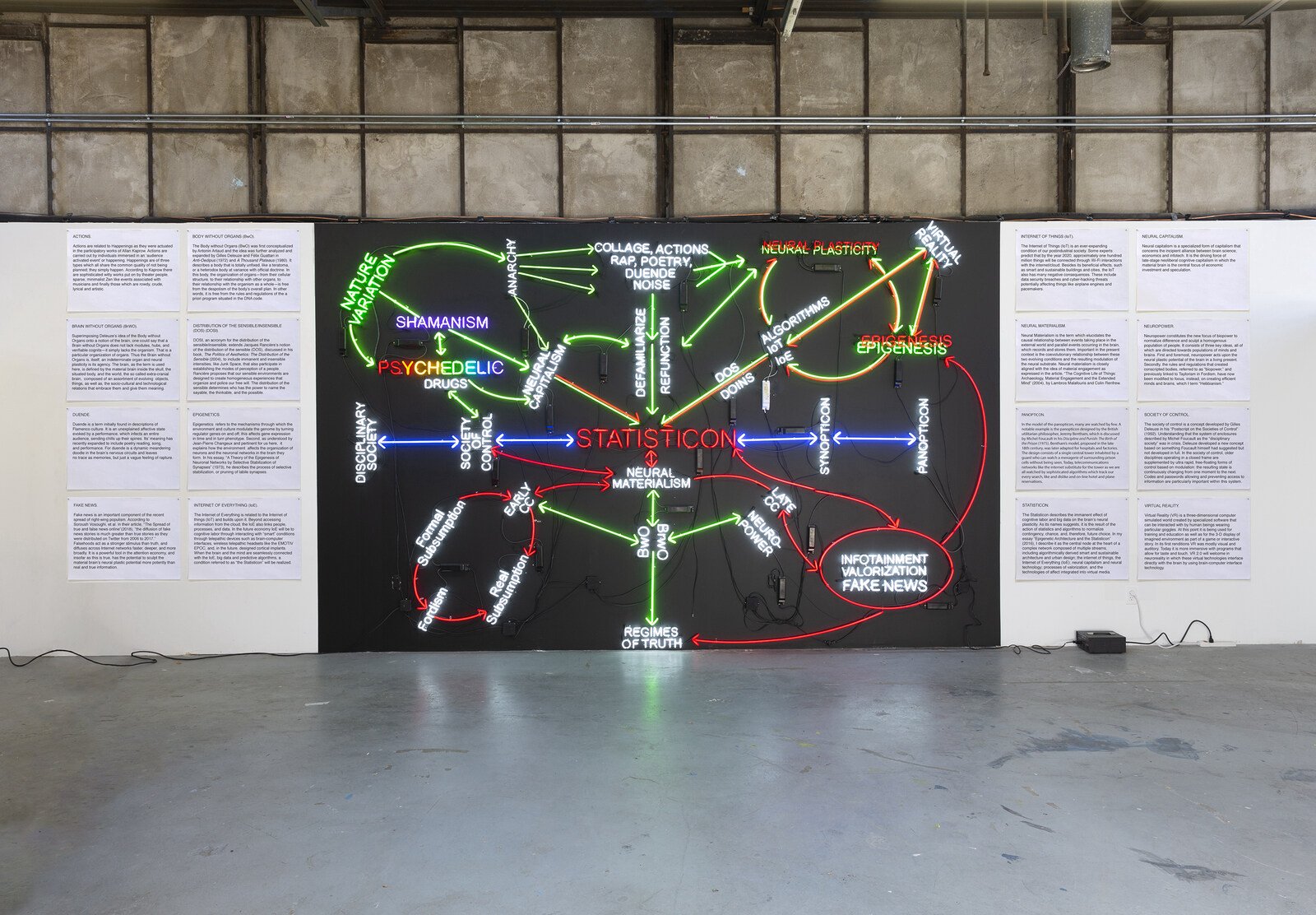

According to Maurizio Lazzarato, this same period also saw the rise of performative and immaterial labor as the predominant forms of work – key characteristics of what would later be known as early cognitive capitalism. Lazzarato described immaterial labor as special because it produces non-material products such as knowledge and information. It also extends to domains historically outside industrial production, including affective and emotional responses, beliefs, and care labor – what Silvia Federici famously identifies as the unpaid affective labor traditionally assigned to women. This expanded scope of labor, including its appropriation of emotions and affect, has become central to the workings of contemporary capitalism. Social media is perhaps the clearest example of this dynamic. My sculptural work, The Statisticon Neon, illustrated these ideas especially as they concerned the emergence of a new form of neural-digital despotism that followed the disciplinary society and society of control.

JC: How does this emphasis on immaterial and affective labor impact artistic practices, both historically and in contemporary contexts?

WN: This shift toward immaterial and performative labor has profoundly influenced artistic practices, particularly as a means of resistance to these new forms of labor. It has led to a revival of performative artistic practices originally developed in the late 1960s and 1970s, but which largely went dormant during the 1980s and 1990s. By the early 2000s, however, the social, political, cultural, and technological conditions of the knowledge economy converged to create a fertile environment for their resurgence. This has sparked renewed interest in artists like Carolee Schneemann, Anna Halprin, Simone Forti, and Yvonne Rainer, whose work foregrounded performative labor. It also had a profound effect on conceptual art as the emphasis on the immaterial object shifted to a focus on immaterial labor. As a result of a perfect storm of new social, political, and economic relations, as they were reflected and redefined in the face of cognitive capitalism, Dry Conceptual Art – the one we already associated with conceptual art from 1965-1972 – was joined by Wet Conceptual Art. Like the dry variety it too was non-representative, text based, and philosophically engaged, but it was colorful, performative, overtly political, and material rather than immaterial. And many of the key practitioners were women and people of color.

Importantly, immaterial labor has the capacity to generate new subjectivities, enunciations, and social relations. It is not confined to the economic realm but becomes a social, political, and cultural force. Paolo Virno observed that immaterial labor is unique because it often leaves no tangible trace – whether after a political rally, a virtuoso piano recital, or a poetry reading – once the event is over, its impact exists only in the memory of its participants. Today, however, we are at the threshold of another transformation in labor – a transition from early cognitive capitalism to late-stage cognitive capitalism, to what I call neural capitalism – in which the material brain or the neural commons is the new sight of capitalist adventurism.

JC: What distinguishes neural capitalism from earlier iterations of cognitive capitalism, and what challenges does it pose for artists?

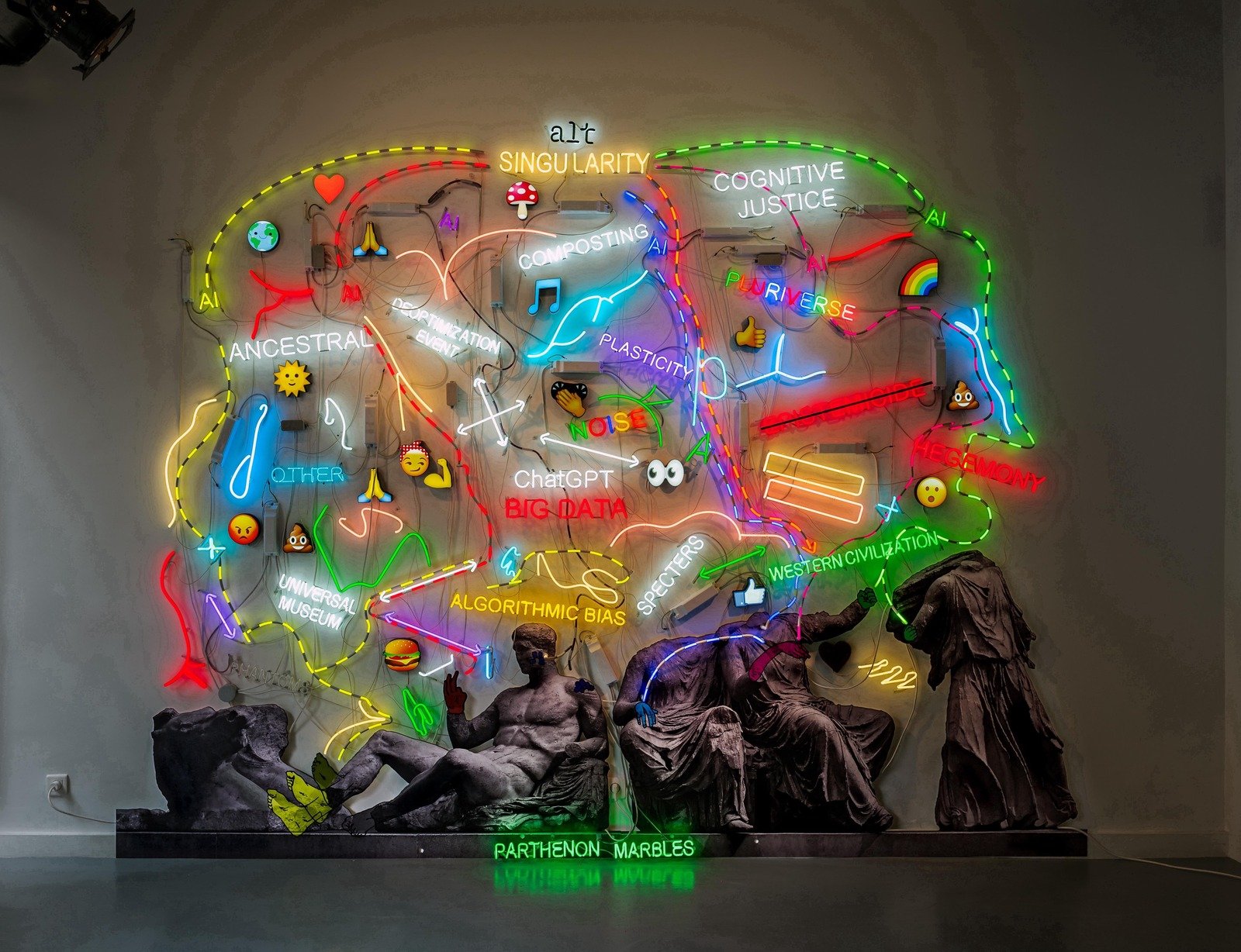

WN: Neural capitalism marks a new phase where immaterial labor becomes entangled with the material brain, leaving physical traces at the synaptic level as memories that can later be retrieved. It affects both phyletic memory – memory shared across the species – and individual memory acquired over a lifetime. Under neural capitalism, neuroscience increasingly collaborates with corporate and military funding bodies such as DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), Facebook, Neuralink, and OpenAI to exploit the brain’s neural commons – its variation, plasticity, and capacity for memory. This was the basis of my work A Proposition for an alt-Parthenon Marbles: The Phantom as Other in which the entanglement of neural networks and artificial neural networks becomes the basis of a deep-learning neural network structure. In this case, the inner layer of the neural network, which samples different fields of data, is the result of on the one hand, the scientific-logic of the Enlightenment, represented by the classic Greek sculpture the Parthenon Marbles, and on the other, that which is gleaned by the sensations and pain of a non-existent phantom limb phenomenon and its metaphors such as ghosts, others, queer, ancestral, and opaque ways of knowing. These inputs collaborate to sculpt and prune the synaptic weights that make up the hidden or middle layer, resulting in what I refer to as the alt-Singularity in opposition to the technical Singularity described by Ray Kurzweil. The alt-Singularity is a type of super collective intelligence that is not built by optimization but instead, by noisy and chaotic inputs leading to a loving, caring, democratic form of algorithmic governance. Singularity in this technical context refers to the moment when asking a question to an artificial intelligence, its answer will be indistinguishable from human intelligence, which will overtake it in time.

For artists and experts in visual culture, it is crucial to understand the languages of these new forms of capitalism and resist being co-opted by them. Particularly as they are subsumed by positivist neuroaesthetics whose research is instrumental in designing and saturating the visual field on screens, phones, and iPads as means to extract data to be monetized. Deploying strategies developed in the lab to capture and exploit gestalts and affordances in the visual field, it has been upgraded to coerce and manipulate user attention and surplus mental labor. I have used the expression “the superordinate precariat” as the state of subjectification at hand today.

At SFSIA, we see these technologies and their performative elaborations as emblematic of the latest phase of the Anthropocene and its intersectional practices, such as the Plantationocene. The Plantationocene, a term introduced by Donna Haraway in 1985, describes the extractive, enclosed plantation model that, as Katherine McKittrick argues, later informed the Fordist industrial factory. Understanding these genealogies is critical to addressing the intersections of labor, technology, and the environment.

Our purpose at SFSIA is to educate participants and enhance their awareness of these shifting paradigms so that they can develop new strategies of resistance and care for the planetary mind and brain. By equipping artists and theorists with this knowledge, we aim to foster practices that challenge and reimagine the dominant systems shaping labor and culture today.

JC: Your comments touch on the pervasive influence of neural technologies within cognitive capitalism. Could you expound on how these technologies intersect with the Anthropocene and broader frameworks of planetary ecology? How do they reshape the cultural and intellectual architectures that artists and theorists must navigate today?

WN: Sure. First of all, the Anthropocene, or the “Age of the Human,” was introduced by Paul Crutzen to emphasize the significant role humankind has played in transforming the geology and ecology of the Earth. The causes of these transformations are human-driven, and include changes to:

- The biological fabric of the Earth.

- The stocks and flows of major elements in the planetary machinery, such as nitrogen, carbon, phosphorus, and silicon.

- The energy balance at the Earth’s surface.

Crutzen and others have argued that these interventions will result in a planet that is biologically less diverse, less forested, much warmer, and increasingly tempestuous. Importantly, the technical ontogeny that initiated the Anthropocene is ongoing, and its effects are not limited to the Earth’s systems but are circling back to affect human beings themselves.

According to Bernard Stiegler, the technical and neural ontogenesis that has defined human evolution over the past two million years – particularly in the last 150,000 years – has been shaped by a co-evolutionary process. This process includes fire, spear-point technology, slash-and-burn agriculture, the steam engine, the atomic bomb, and, more recently, ChatGPT. Alongside these technological developments, there has been a parallel enlargement of the frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes of the brain. Stiegler describes this dynamic as maieutics or mirroring – a progressive feedback loop where new technologies reverberate through the architecture of the brain changing it, which in turn, activates alternative cultural dispositions thus perturbing and transforming it. These altered cultural dispositions then sculpt new neural networks ad infinitum.

To differentiate this phenomenon from the slower evolutionary processes of genetic mutation and natural selection (endosomatic organogenesis), Stiegler introduced the term exosomatic organogenesis. This refers to the evolution of external, artificial organs or tools (tecnics) that are internalized by the brain as inorganic extensions entangled with its neural networks. The invention and application of these techniques has been accelerating. This process is a pharmakon – having potential to both subjugate or proletarianize the subject as well as emancipate them. For instance, the Anthropecene and its technics have resulted in the process of hominization over the past two million years, creating what I term the “anthropocenic brain” and its corresponding noetic (intellectual) counterpart. The human cognitive apparatus organized according to its logic has formed a consciousness that is delineated by a desire to conquer and subjugate nature for the purpose of humanity. The destruction of the planet and the inability to act against the imminent sixth extinction event is the result. But this same process is still ongoing, and neural variation and neural plasticity can be sculpted according to emancipatory logics. In my opinion, art plays an important role in this process.

JC: Excuse me for interrupting but before you go on to tell us how this is possible, I would like to dig a little deeper. How do neural technologies such as optogenetics, brain-computer interfaces, and Chat GPT fit into this framework, and what role can art play in reshaping their trajectory?

WN: Recent neural technologies, such as optogenetics, brain-computer interfaces, and ChatGPT, are the latest additions to the lineage of anthropocenic technologies. The process of exosomatic organogenesis continues to evolve, affecting us in ways we cannot yet fully understand. However art, when delinked from the market, operates as a technology of emancipation – a healing pharmakon. It entangles itself with the process of exosomatic organogenesis, acting upon the brain’s potentiality to become other. Acting on its massive variation as a poetic and destabilizing force it creates new neural networks and pathways of noetic freedom.

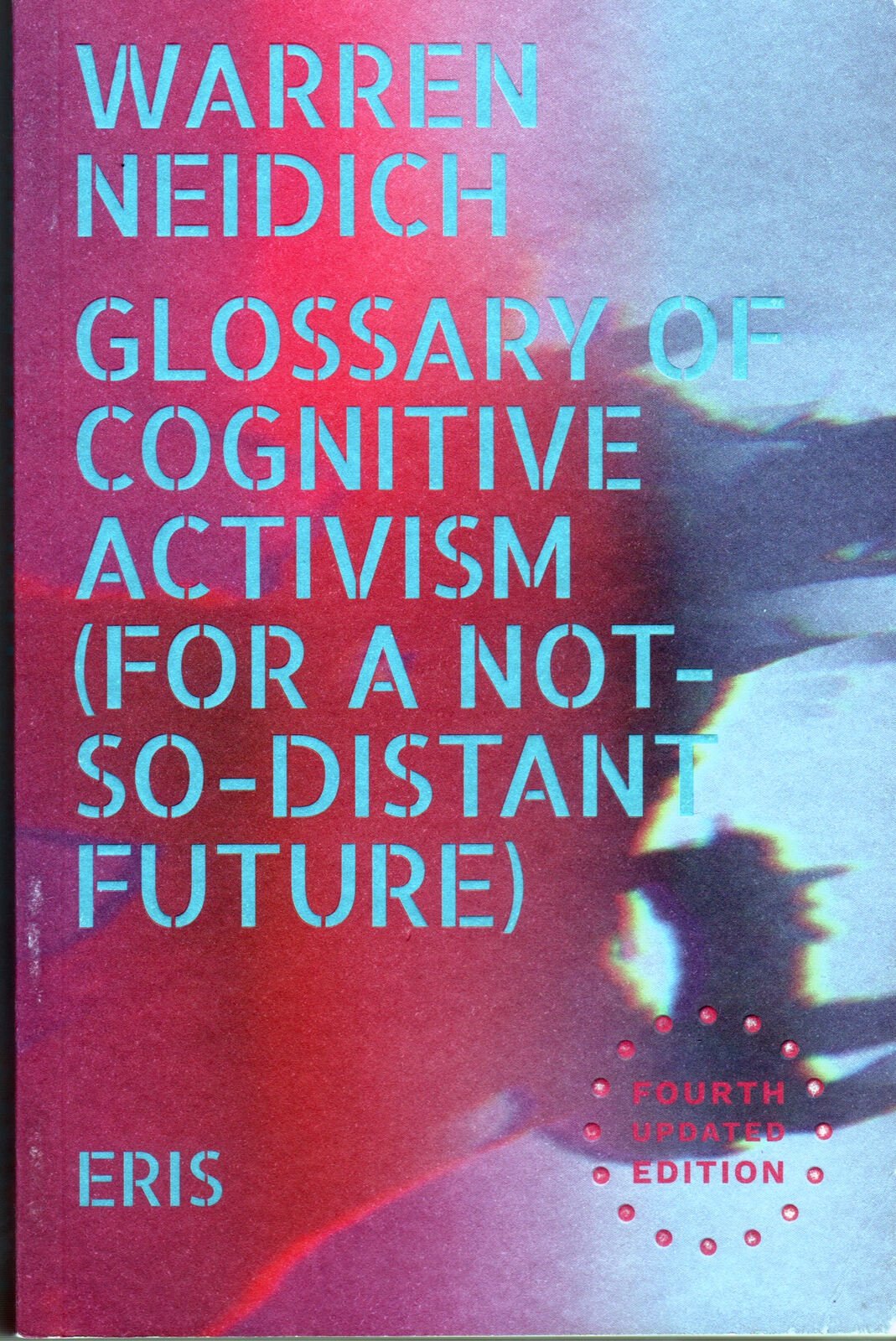

By connecting theories such as Gerald Edelman’s theory of neuronal group selection, Jean-François Changeux’s theory of synaptic epigenesis, and Stanislas Dehaene’s neuronal recycling hypothesis, I suggest that exosomatic organogenesis continues to instigate changes in the brain. These changes provide reasons for hope. In my Glossary of Cognitive Activism I dive deeply into this subject matter.

JC: You mention hope. Could you elaborate on how we might move beyond the Anthropocene toward a more ecologically harmonious framework?

WN: I propose the possibility of a new species of technics, one guided by the principles of deep ecology. These ecocenic technics prioritize care for nature and value the planet beyond its utility to humankind and capitalism. An example of such a technology is Ayahuasca, which opens us to suppositions of deep ecology, fostering a broader sense of care for the planet and a recognition of humanity’s place within multispecies phylogenesis.

Through this framework, I envision the production of an ecocenic neural-technical mutation – a shift that could lead to an ecocenic neural architecture and its corresponding eco-noetics. This process would replace its anthropocentric counterpart and guide us toward a new era of eco-planetary sapienization, characterized by a deeper understanding of humanity’s interconnectedness with the web of aliveness on Earth.

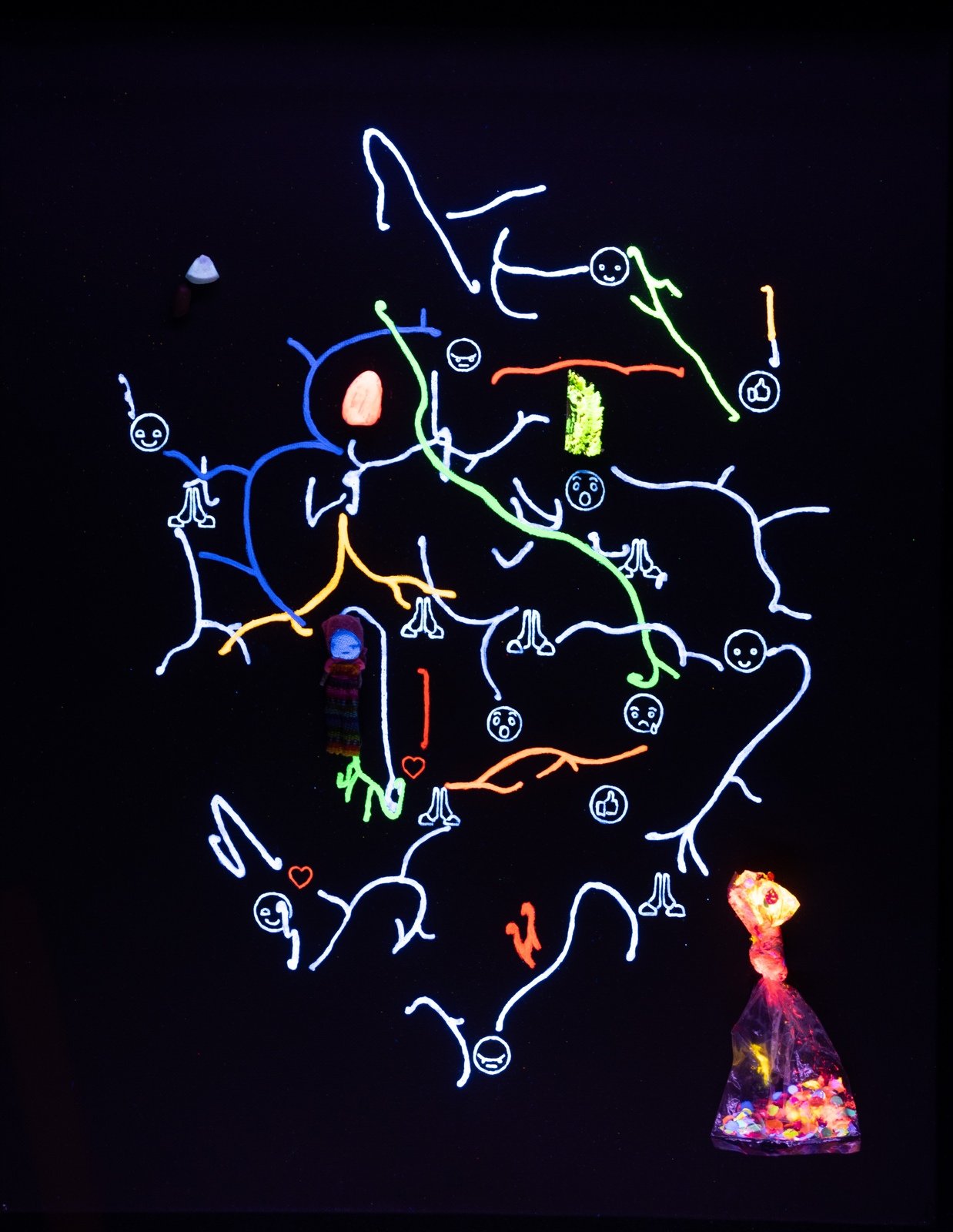

In this sense, art and theory have a critical role to play in shaping these transformations. By fostering awareness and alternative modes of engagement, they can contribute to a reimagining of planetary and neural architectures that promote care, interconnectedness, and ecological balance. Indebted to Latour and Steigler, this ecocenic, exosomatic organogenesis and eco-planetary sapienization is the subject matter of my neon sculpture the Brain Without Organs as well as my blacklight paintings of the same name.

JC: Could you elaborate on how a recent program of the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art in Berlin, held during the pandemic at Kunstverein Rosa-Luxemburg-Platz, along with a related exhibition there, developed some of the themes you mentioned earlier? It was called Activist Neuroaesthetics, correct?

WN: Yes, that’s right. The program included both an exhibition and a symposium, both titled Activist Neuroaesthetics. The symposium resulted in a publication, An Activist Neuroaesthetic Reader, which was edited by Sarrita Hunn, Assistant Director of the Saas Fee Summer Institute of Art and myself, and published by Archive Books. Contributors to the volume included Franco “Bifo” Berardi, Elena Agudio, Ina Blom, Yann Moulier Boutang, Juli Carson, Yves Citton, Cécile Malaspina, Anna Munster, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, Reza Negarestani, Dimitris Papadopoulos, Luciana Parisi, Victoria Pitts-Taylor, Tony David Sampson, Tiziana Terranova, Anuradha Vikram, Elisabeth von Samsonow, Charles T. Wolfe, Slavoj Žižek, and myself.

The exhibition Activist Neuroaesthetics was structured around three thematic sections: Brain Without Organs, Sleep and Altered States of Consciousness, and Telepathy and New Labor. It was co-curated by Susanne Prinz and me.

The first section, Brain Without Organs, really explored issues of neural plasticity and exosomatic organogenesis. It drew inspiration from Antonin Artaud’s concept of the Body Without Organs (BWO). The BWO challenges the organization of the body’s organs, freeing it from the autocracy of genetic, social, and political codes, such as those that dictate sexual modesty. While the BWO countered the forces of control acting on the proletariat body in Fordist factory work, it is insufficient to do so in the context of cognitive capitalism. Today, the laboring networked mind has replaced the assembly-line body, necessitating new strategies of resistance. In this new phase, tools like memes, fake news, clickbait, and advanced digital design techniques – once developed for game design – are repurposed to capture the attention of the cognitariat, or mental laborer, generating surplus mental labor. Brain Without Organs is a new framework which resists the stultifying and despotic qualities of the neural-digital entanglement.

The second section, Sleep and Altered States of Consciousness, featured artists like Elena Bajo, Katie Grinnan, Karen Lofgren, Tino Sehgal, Jeremy Shaw, Suzanne Treister, and Rosemarie Trockel. This section examined the thin veil separating sleep from altered states of consciousness, as both involve temporary changes in mental states induced by neurochemical stimulation. It referenced Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), which depicts the effects of mass insomnia in a 24/7 lit environment, leading to cognitive breakdowns and hallucinations. This section emphasized how sleep and altered states remain stubbornly resistant to commodification under neoliberal capitalism. Psychoactive substances, for example, expand consciousness and produce alternative cognitive strategies that resist capitalist control.

The third section, Telepathy and New Labor, was a collaboration with artist Jacqueline Drinkall. It explored the implications of emerging neural technologies, such as brain-computer interfaces which intercede between the intracranial brain and its extracranial milieu. These technologies are being developed in response to the demands of advanced digital labor, increasing the speed and intensity of mental work to extract surplus value. Artists in this section, including Kathryn Andrews, Simon Denny, Suzanne Dikker, Marina Abramović, David Horvitz, Agnieszka Kurant, Jonathan Monk, Gianni Motti, and Lorenzo Sandoval, investigated how these technologies reshape labor and subjectivity.

Through these exhibitions and programs, SFSIA not only engages with pressing contemporary issues but also equips participants with critical tools to navigate and resist the forces shaping cognitive labor and cultural production in the 21st century.

JC: The title of this year’s Paris program, The Brain Without Organs: Planetarity, Plasticity, and Eco-Cosmotechnics, is especially compelling. Could you begin by unpacking the key terms in the title and how they frame the theoretical and practical concerns of this year’s program?

WN: Last year we staged our school in both New York City and Paris. Last spring in New York, we collaborated with Creative Time and Montez Press Radio to produce a program titled Art, Apparatus, and the Neural-Digital Entanglement. Our program in Paris followed-up on the New York City program and concluded just last week (October 2024). It was titled The Brain Without Organs: Planetarity, Plasticity, and Eco-Cosmotechnics.

I already defined the Brain Without Organs earlier in relation to the first part of our exhibition Activist Neuroaesthetics. The term, as mentioned, is borrowed from Antonin Artaud’s concept of the Body Without Organs (BWO), further elaborated by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in their works A Thousand Plateaus and Anti-Oedipus. The BWO is a means of emancipating the body from its organs, freeing it from the debilitating effects of governmental programmings and biopolitics in the Foucauldian sense. Biopolitics here refers to the administration of life, where populations are policed and regulated to sustain and multiply life in contradiction to the repressive and negative juridical-discursive power, which operates by enforcing limits and invoking lack.

The BWO is directed toward resistance against juridical-discursive power and its restrictive mechanisms. A clear example of this is Paul B. Preciado’s political performance of taking testosterone to undo or modify imposed notions of gender. This act challenges biopolitical control over bodies by intervening in the social and political systems that assign and enforce identities.

In the same vein, the Brain Without Organs borrows this concept of the unassigned body and applies it to the brain. Although the brain is part of the body and therefore subject to biopolitical regulation, I coined the term “neuropower” to describe the intensified focus on controlling the brain, particularly through its neural plasticity. The Brain Without Organs becomes a metaphorical and political tool for emancipating the brain from both genetic determinism and the socio-political and cultural forces that attempt to manipulate its plasticity in order to produce a brain with organs that is neural normative, in a social capitalistic sense.

JC: How does neuropower specifically relate to the concerns of this year’s program?

WN: Neuropower emphasizes the control exerted over the brain’s plasticity – its ability to change and adapt – both as a means of coercion and as a potential site of emancipation. The Brain Without Organs describes a political performance in which the brain is freed from the influence of both genetic and socio-political constraints, allowing for neural diversity and openness. Sovereignty in this context is not about life and death but about determining the brain’s variability and potential for adaptation.

The challenge lies in resisting efforts to constrain neural diversity, which often results in the production of controlled, normalized subjects: the perfected digital consumer whose brain and consciousness intertwined with the algorithmic governmentality of the internet. On the other hand, the Brain Without Organs seeks to enable neural openness, fostering a brain that is not only adaptable but also capable of resisting coercive forces. This framework ties directly to the broader concerns of this year’s program, which interrogates how the brain’s plasticity intersects with planetary, political, and ecological forces.

JC: The concept of “planetarity,” as you employ it, seems to signal a rethinking of geopolitical and ecological paradigms. How does this term extend beyond the Anthropocene’s prevailing narratives, and what implications does it have for fostering a more interconnected and equitable planetary consciousness?

WN: The term planetarity, as framed in this year’s program, does not refer to its common usage in discussions about Earth’s place in the universe, extraterrestrial life, space travel, or even terraforming and geoengineering. Instead, it describes a method of thinking that transcends the limitations of the nation-state, particularly in relation to economic competition, and advocates for a language of coexistence that promotes planetary habitation and perpetual peace.

Furthermore, planetarity is a hopeful concept. It suggests that through mutuality, epistemological diversity, and what some have called “cognitive justice,” we may address one of the most critical challenges of our time: the Anthropocene. Over the past 100,000 years – and especially during the accelerated transformations of the last century – humanity has experienced a profound alienation from nature. Initially, this alienation manifested as a desire for protection from nature; later, it became a drive to conquer it.

This alienation reached a significant turning point when the first images of Earth, taken from the Moon, entered the collective consciousness. According to Marshall McLuhan, this event fundamentally altered our perception of nature. No longer seen as a static entity, nature was reimagined as part of a dynamic, interconnected system – a shift that introduced the concept of ecology. This transformation was further developed through James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis, which described Earth as a cybernetic system in homeostatic equilibrium.

Building on these ideas, planetarity invites us to envision a new form of sapienization: eco-planetary sapienization. This concept describes the emergence of a situated human being with an expanded, ecocenic brain, shaped by new forms of technological accumulation and ecological awareness. It is a vision of humanity rising from the ashes of its own imminent extinction, transformed by the very forces threatening its survival.

This, in essence, is the deeper meaning of eco-cosmotechnics. The Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art has become a forum for discussing and speculating on what this vision might mean for the future of civilization, inviting participants to collectively imagine new pathways toward planetary consciousness and ecological coexistence.

JC: Extremely thought-provoking, Warren. Looking ahead, could you share your vision for SFSIA’s future? Are there any emerging themes or geographic expansions you’re particularly excited to explore in the coming years?

WN: We are planning three programs next year. We will return to New York and Paris, and we have also accepted an invitation to bring the school to Vancouver. As for the topic, it’s still up in the air at this moment. The Paris program was so successful, and there is still so much ground to cover, that we might consider a second school in NYC dedicated to The Brain Without Organs: Planetarity, Plasticity, and Eco-Cosmotechnics. This time, instead of relying primarily on a European faculty, it would be exciting to invite contributors from North America and South America. The Paris program will be a collaboration with the Martine Aboucaya Gallery and Maison Suger. I have invited the French curator Matheiu Copeland to co-curate Wet Conceptualism in Cognitive Capitalism which will be both the subject of the school and the title of the exhibition which will be held at the gallery.

Additionally, I will integrate the school into my exhibition in Vancouver at a space called Gachet, and will collaborate with former Saas-Fee participant Sol Hashemi. This is going to create a unique platform for SFSIA, blending the school’s pedagogy with a public-facing exhibition.

JC: Thank you, Warren.

Warren Neidich is an artist and writer who works between New York City and Berlin. His multidisciplinary artworks explore the intimate relationship between cultural plasticity and neural plasticity, resulting from the transformation of industrial to cognitive capitalism. He is the founder and director of the Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art and a contributing editor at Bomb Magazine.

Józefina Chętko is an artist, Professor of Professional Practice at Barnard College, Columbia University, and co-founder of the artist collective Lou Cantor. Her work explores intersubjectivity and interpersonal communication, engaging with the polysemic nature of contemporary media.