Lea Sande

The 30th edition of the International Festival Of Computer Arts (MFRU) curated by Lara Mejač and Davide Bevilacqua is a display of technologies’ sometimes forgotten or misplaced role in capitalist consumer societies. It asks us to envision what the future would look like if we were to reconsider the ways in which technology interacts with society, upholds the relations of power, or discourages different ways of building communal alternatives. Focusing on critiques of modern technological implementations that we consider ubiquitous by calling out their absurdity, it dares the visitor to drastically change their perspective. It approaches the subject with zero moralism or apocalypticism, with a genuine understanding of technology so it can establish a space where visitors are free and compelled to consider the authors’ visions or interpretation of the past, present, and future. Some of the works achieve this through humour and irony, others simply by presenting information and asking visitors to draw their own conclusions. There are hardly any high–tech elements or cutting edge innovations present, showing us that what we already have is enough to conjure up new and exciting ways of interpreting and organising the world around us.

The main exhibition of this year’s edition, titled: Off the Shelf. Post-Consumerist Imageries When the Business Left the Building was located in the city centre of Maribor in a building commonly referred to as Velika kavarna or The Grand Cafe. The building has lived many lives and its story as the festival’s facilitator plays very well with the themes the exhibition explores. At first considered a common gathering place for the town’s German-speaking noble class, its next iteration was a casino which went bankrupt in 2009. It was last in use as SALON UPORABNIH UMETNOSTI or The Salon for Applied Arts, a focal point for local artists and creatives. Now it stands half empty, its walls carrying the remains of the past knowing far too well what it’s like to spiral through the relentless cycles of capitalism. That’s why for a short time at least, the space was brought back to life with works and installations that try to reinterpret and recontextualise the history of the location itself and conceive of new futures that might be possible if we were to reimagine its functionality. The exhibition is shaped in a way that presents alternatives to spaces we would often find in an everyday shopping mall. Instead of a cafeteria or a food court we could replenish our hunger in the “Social Nourishment Court” or educate ourselves and safely experiment with new radical ideas in the “Economic Potential Laboratory.”

Along with the main exhibition, the festival also took some time to reflect on its past. In the thirty years of its presence, computer science and technology as a whole has taken quite a significant leap. The exhibition 30×MFRU, Three decades of worrying about technologies takes us on a tour through the thoughts of past participants of MFRU. The curators, artists, and theoreticians share their perspectives on what kind of impact the festival has had on the local and international stage, what have been the main challenges they faced while displaying intermedial art, and if at this point it is even appropriate to call it computer art anymore. Next to the display of archival footage from the bygone editions on a set of monitors laid a stack of publications with the collected interviews of the participants which can be also explored virtually in the form of a website.

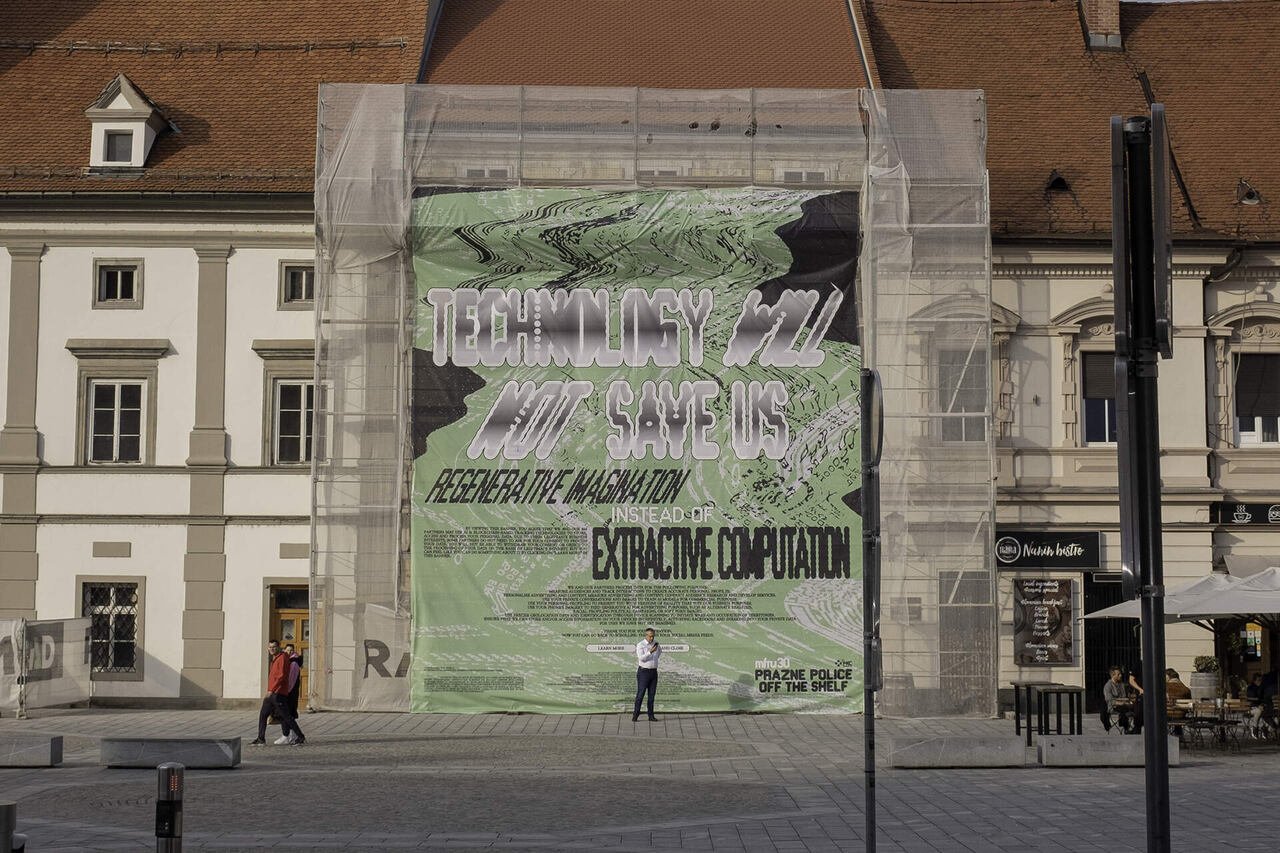

Before stepping in the building, Maribor’s citizens were greeted by a public intervention. On the side of the building standing exactly opposite from the exhibition entrance, we could see an enormous print that read: Technology will not save us, regenerative imagination instead of extractive computation. The call is clear – without comprehensible means and a vision, pure technological development will not be enough to guarantee a bright future, save us from inequality, or resolve the complex web of problems that we refer to as climate change. At the same time the other option, to detechnologize, is not viable either, because disregarding the systems we have become so dependent on would set us back and at the same time would not yield productive results (Papamattheakis, 2020). The solution shines in ways of “disrupting the disruptors,” to momentarily put aside the ideas of designing planetary computation that involves cooperation of different layers of the stack on a global level (Bratton, 2015), as in this context it seems utopian, but on an individual or community level, to create concepts and models of alternative being, seems achievable. If they can stretch time and scale they might be able to operate on a level that could pose a real alternative, even if on smaller scales (Lovink, 2020).

The first area of the exhibition – The Social Nourishment Court – consists of a cafeteria layout full of plastic tables coupled with chairs and a small refrigerator. Inside the white walls of the appliance lies a smart tablet displaying a youtube video. On a shelf next to some cheese we can watch a cooking tutorial on making a grilled cheese sandwich. The work Dasha’s kitchen: My Magical Grilled Cheese Sandwich Recipe by Dasha Ilina is a critique of our common misunderstanding or oversimplification of how computer algorithms work. Algorithms are often explained as a simple set of step by step instructions that the computer must follow. That is why they are commonly compared to a recipe for a grilled cheese sandwich – you read the input, apply the cheese, crunch a few numbers, add the butter to the pan, return the value to the second function, and the result is a tasty treat. These days computer algorithms are much more difficult to explain, that’s why we use the metaphor of the black box. We really don’t know how our meal is made anymore, we just input the ingredients, they are processed and put together in unknown, maybe even unthinkable ways and spat out at the other end of the machine. As algorithms, especially with the help of deep learning, become more and more complicated and abstract, the simple metaphor of a grilled cheese sandwich does not suffice anymore.

One of the more important shifts in computer science has been the move from linear to object-oriented programming. Through this distinction we could think about the break between modernism and postmodernism or even disciplinary societies and societies of control (Galloway, 2006). While both follow the structure of a grilled cheese sandwich in the sense of simply following instructions given to them by the programmer, object-oriented programming has opened up a new way of building, and more importantly, maintaining much more complex systems than the preceding paradigms. But the more important distinction yet, when it comes to algorithms, is the one between traditional programming or hand-crafted programs on one hand and deep learning or artificial intelligence on the other. We have long been thinking about machines as mechanistic, as simple tools which make our everyday lives easier with externalisation of labour. At first this was physical labour, with machines like pulleys or ploughs which later progressed to mental work with writing and calculations. Today we can no longer claim that computers fall under the classification of mechanistic as, along with the development of AI, they are capable of pseudo–intuition (Parisi, 2015).

Maybe the best way we can try to understand the ever evolving algorithmic production is to have an open mind – we should not limit machine intelligence to just a copy of our own, we should let inhuman intelligence form on its own and maybe find new connections. We should also try to demystify technology and avoid doomsday explanations as they are never productive (Hui, 2023). At the same time we are facing increasing difficulties in regulating the learning processes and implementing these technologies. How can we limit the obsessive web scraping, modelling of consumer habits, or implementation in drone recognition services? We first need to understand that it is not as simple as a grilled cheese sandwich anymore. We are dealing with tangible, maybe even inhuman forms of intelligence as opposed to a simple list of orders which accordingly call for systematic regulation and implementation.

The Social Nourishment Court was also home to another work titled Discount Cui-Zine by Simon Browne and Alice Strete. Through a workshop, the artists worked together with the visitors to create zines from promotional grocery listings. They were tasked with making a collage that would display their eating habits or try to challenge the ways in which food brings us together.

The Temple of Eternal Return was situated in the conference room of the old casino. Waiting for the participants were plastic chairs paired with the typical complementary branded bottled water. FTC Future Trainarium Center by Freštreš, invited us to participate in a pyramid-adjacent work organisation model with three stages: KOworking, KOnzumlate, and KOrpus. The motivational recruiting video promised escape from everyday sorrow, unimaginable rewards for an undisclosed amount of labour, and validation in the form of belonging to a bigger corporation. By watching the video we slowly realise that the victims signing up for FTC are neither getting any benefits nor ever advancing to the next tier of “konzuming” the fruits of their labour. This critique of modern platform capitalism very clearly demonstrates what a lot of these companies offer – a low income job that someone would pick because of false promises of promotion which actively prohibits and sanctions worker organisations and unions, like Amazon’s anti–union training video. As a final touch, if convinced by the persuasive video performance, the visitor can choose if she wants to sign up by giving away her fingerprint scan. As all platform economies operate on the basis of extracting as much value out of raw collected user data as they can, be it voluntarily or by tricking its users (Srnicek, 2017), this seems a fitting last act of exploitation by FTC.

Although we have been externalising as much work to machines as we can, we still haven’t been able to mechanise our production or consumption of luck. Off-the-shelf MOCHI – Post-capitalist gym located in the Post-Consumerist Training Corner offers a physical drill meant to increase our odds of struggling against luck. The installation is a play on the common Japanese saying which translates as “to catch a Mochi off a shelf,” meaning to have such blind luck that while pacing through a store, a mochi rolls off a shelf directly into your mouth. The training apparatus is designed for the visitor to insert a mochi from a pile nearby and elevate it with a simple pulley system. After that, the sweet treat rolls through an assortment of shelves, courtesy of Velika kavarna, and falls off at random intervals. The visitor’s job is to be prepared for the fall and intercept it, to be ready for consumption.

That is not the only training that can be done at the exhibition though. Dasha Ilina’s second set of installations combined under the name HTTP (Human Tips for Technological Problems) encapsulated in the Holistic Tech Center can teach us how to disarm someone if they are too deep in the feed, or how to protect yourself from common dangers such as dropping your phone on your head while scrolling before bed. It also shows a series of interviews about technological folklore, like burying your phone in rice if you drop it in water or using super glue to fill in the cracks of your screen.

The Economic Potential Laboratory is a part of the exhibition where possible futures are formed in the most tangible way – less speculations or critiques and more methods of conveying information about possible changes to our current socio–economic regime. Rok Kranjc’s Game-Changers: The Generative Collectible Futures Marketplace is a board game that challenges players to test their political, ideological, and economic beliefs by arguing for one of the opposing sides, co-opting neo–economic buzzwords while using cards that display possible futures. The two rival teams – capitalism and communism – fight over control of buzzwords like “posthuman,” “sharing,” or “cooperative” by using prompts including words prescribed in the transitional areas like “copyleft” or “something DAO.” Their act of conquering is done by pitching short stories using the cards they are dealt – like arguing how crypto can be the last nail in the coffin of capitalism.

Using science fiction to predict alternative modes of production or radically different structures of society is not as far-fetched as it may seem. Many great changes in history can be retracted or retrospectively viewed as complete left turns or unpredictable outcomes. At the same time, economics is not a science working in a system as clearly and neatly defined as physics, although economists like to look at it in that way. From this perspective we can see how most economies’ “scientific natural laws” come from a change in technology, policy, or act of an organised group (Davies, 2018). While playing the game, players must also argue points in which they sometimes do not believe in order to get the audience’s approval. In that sense it is very similar to how teenagers online choose different radical ideologies, with sometimes exclusionary belief systems, and for a while they might argue for one, and then another, and they sometimes pick them apart and recombine them to their own liking (Citarella, 2022). Trying out political views like different pieces of clothing can help you better understand your opponents counterarguments and at the same time reaffirm or change up some of your own. Maybe most importantly, it opens up the spaces in between for new and potentially revolutionary parallel universes.

The second part of the Economic Potential Laboratory consists of Pablo Somonte Ruano’s pocas (poca organización cooperativa de autoservicio). A computer screen surrounded by AI-generated visions of an alternative version of present-day Mexico City is showing us a detailed and developed theory that is running the analogous post–capitalist rendition of the city. pocas shows us a network of self-governed and collectively owned convenience stores that would be possible by implementing new technology in older mutualist practices. Most commons are defined by being taken care of by a network or a community and by being able to solve people’s concrete problems and meeting their needs (Bollier & Helfric, 2015). Examples from pocas include a grid of convenience stores that supply contraception and resources for safe abortion or even supplies for hormone replacement therapy or IVF treatment or transgender affirming care. We have seen numerous cases of research in new technologies – infrastructures or practices that could help many underprivileged or marginalized people in a very beneficial way – being discarded because it wasn’t profitable (Medak, 2016). pocas shows us that a real, palpable replacement for our current dysfunctional system of care is possible, and it might not even be that out of reach.

At the Nostalgic Rituals Outlet we were able to observe a colorful minimalistic and futuristic installation called Beauty Stand, 3005 by Xcessive Aesthetics. The work, in all its shiny plastic, is trying to commemorate the death of the mall. As the internet moved away from its initial dream of an open public space for sharing information and knowledge, it has become completely absorbed by capital. As it was quickly established, the web is the ultimate interface for both marketing and shopping, swiftly reconfiguring social relations that were in place before the widespread use of the new technology. As the internet started to rent out plots for virtual stores, which gathered more and more traction, it had an impact on our shopping habits as well. Instead of going to the mall with a couple of friends or our family members we can complete the entire shopping process through a web page or even more commonly now, through an app. The feeling of interacting with a false storefront instead of actual people is being invoked by a single, deconstructed store shelf placed in an empty room. In the top part there is an integrated smart tablet that presents filters reminiscent of those we would find either on our social media platforms or the ones used to simulate how a makeup product would look on a virtual shopper.

Even though for some, the mall represents everything wrong with our modern consumerist society, it cannot be denied that it spawned new and unique social and spatial relations. As a non-place it played a big role in steering modern architecture and urbanism in a new way as well as gave the field of sociology a completely new playground to study. But like most practices, it was clear that shopping would at one point become too physically demanding and would soon expand its services to the digital realm (Jameson, 2003). The shopping mall experience was mainly targeted towards young girls, as they were very quickly chosen as the ideal model for inscription. The “Young-Girl” can be thought as a matchmaker between the social practices of the youth and the interests of capital as it (Young-Girl) is both the consumer and the producer (Tiqunn, 2012). On one hand, the Young-Girl is consuming clothing, make-up, food, drinks and media, and on the other, while doing so, she is building social practices that involve herself and her friends – meeting at the mall, exchanging accessories and going to the movies. While consumerism constructed these practices it is also the reason they have broken down as the move to online shopping can not translate the same social relations into a virtual space. Our online consumption has thus become animalised – with no regards to past forms of culture, detached from any grand narratives and most importantly free to recontextualise and combine any elements from the database (Azuma, 2009). We are only driven by the new face of capital – the imperative of cuteness. The wish to become squishier, lighter, and less pointy in a way that is more in line with Instagram filters and less in check with our friends’ actual standards. By shopping and recombining products such as bows, stars, and kitties we are projecting and rewiring the relations to be instead expressed towards and by the moe–elements themselves (Ireland & Kronic, 2024). If the only way to be seen by others is not to hold their hand while strolling through a non–place but to like their post or wait for a reply to a story, we might as well stock up on all the sparkles and hearts to share with each other – but maybe even these won’t last as long as we would like as technology is prone to changing our habits and relations much quicker than we are typically comfortable with.

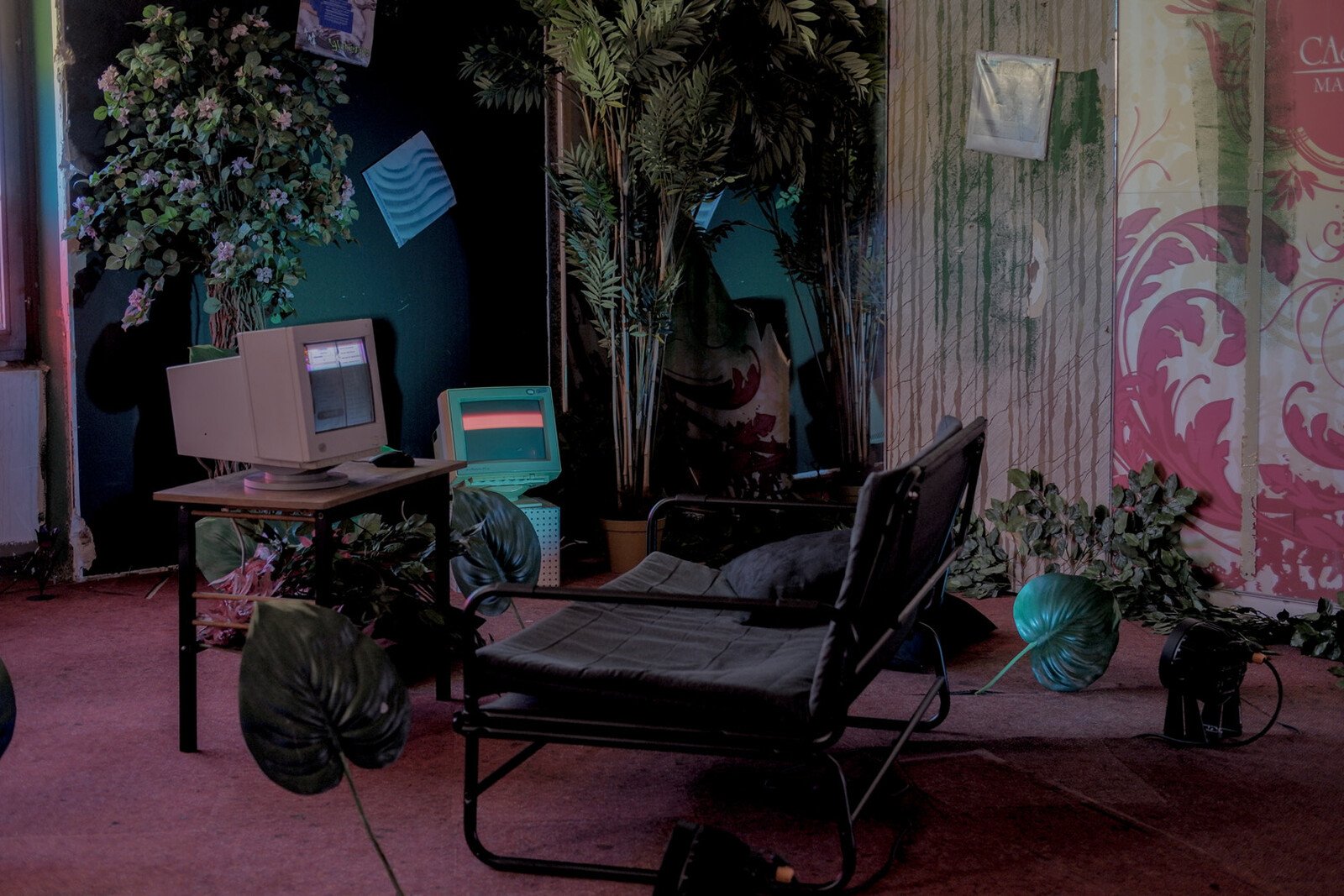

If we moved towards the next work at the Nostalgic Rituals Outlet we would find it surrounded by a barrage of ancient boxy computer monitors bathing in colourful light breaking through a stained-glass window. The room is full of bright neon colours contrasted by broken down pillars and calming sets of tropical–esq foliage. Stepping closer we can hear an unfamiliar but somehow nostalgic tune. N A I V S T A L G I J A by Undoing.Studio is a project that is both reinterpreting the past and creating a new timeline. On the display we can hear a release by a fictional record label called Večni Zadruga titled F U T U R S T A L G I J A, that we can categorise as an ad hoc music genre called Mariborwave. As the name suggests, it is a fusion of the early internet aesthetic that spawned from the music genre vaporwave and the soundscape that influenced the identity of Maribor, among other Slovenian cities. On a buzzing CRT screen we can see a menu full of ex-yu hits that the listener can choose from. Picking a song, we can interact with it through a few sliders that regulate the intensity of cosiness or nostalgia. This generates an eerie ahistorical feeling – the songs performed before the creation of the world wide web now take a form of a specifically internet conceived music style.

Vaporwave’s aesthetic pulls from an early 90s dream of what the internet could be. Visually we can often see statues from Greek and Roman traditions surrounded by the products of hyper–consumerism covered in Japanese text and shades of purple. The displacement of classical art is a play on tradition and nostalgia, trying to evoke a feeling of lost histories that we all long for. Brand logos and products like Arizona ice tea are a display of the capitalist society early internet users grew up in. Part of that was a fascination with the technology that was developing extremely quickly in Japan, hence the Japanese script and cultural references. Together everything is flowing into a state of disenchantment with technology and consumerism, alongside a tiredness from the proliferation of these non–places like malls and airports. Borrowing from its musical predecessor, called hypnagogic pop, we can feel a sort of displacement in these spaces, something in them is deeply known to us but at the same time eerily empty – the hypnagogic state would later became known as liminal (Tanni, 2024). While playing with the sliders on an old monitor and hearing a real time remixed version of an ex-yu classic there are multiple levels of historical disconnection at play at once. Nowhere is this as clear as the medium we are using for displaying the art – be it an old vinyl record with its signature crackle or an old CRT monitor with its buzzing and flickering. This materiality, the physical limits of an old medium that make it unique, is one of the key factors that constitute hauntological music (Fisher, 2014).

Maybe now we can answer the question of what the role of computer or intermedial art is in the current consumerist landscape with much more certainty. It opens up a space of possibilities that we may be willing to only accept through art, humour, or play. If we are willing to step out of the prism of capitalist realism for just a moment, alternatives are not so difficult to grasp. We should find hope in art projects, research groups, initiatives, and squats that are speaking through their work about these radical courses of action and maybe even more importantly, join them in a way that intrigues us the most.

References:

- Azuma, H. (2009). »Otaku : Japan’s database animals.« Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press.

- Bratton, B. H. (2015). »The stack: on software and sovereignty.« The MIT Press.

- Bollier, D. & Helfric, S. (2015). Commons.« In »Degrowth: a vocabulary for a new era.« (2015). Routledge, 102–105.

- Citerella J. (2022). »Politigram & the Post – left.« Substack: https://joshuacitarella.substack.com/p/politigram-and-the-post-left

- Davies, W. (2018). Economic Science Fictions.« The MIT Press, 31–40.

- Fisher, M. (2014). »Ghosts of my life : writings on depression, hauntology and lost futures.« Zero Books, 18-21.

- Hui, Y. (2023). »ChatGPT.« E-flux: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/137/544816/chatgpt-or-the-eschatology-of-machines/

- Ireland, A. & Kronic, M. (2024). »Cute Accelerationism.« Urbanomic, 155-160.

- Jameson, F. (2003). »Future City« [Journal Article]. New Left Review, 21(21), 65–79.

- Lovink, G. (2020). »Extinction Internet.« Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 56.

- Medak, T. (2016). »Shit tech for a shitty world. Aksioma, zavod za sodobne umetnosti.

- Papamatheakis, R. (2019). »Black Natures: Enframing the Natural as Technological.« Strelka Mag: https://strelkamag.yc.strelka.com/en/article/black-natures-enframing-the-natural-as-technological

- Parisi, L. (2015). »Instrumental reason, algorithmic capitalism, and the incomputable.« In Pasquinelli, M. Alleys of your mind, Meson press, Lüneburg, 125-137.

- Srnicek, N. (2017). »Platform capitalism.« Polity, 39-40.

- Tanni, V. (2024). »Exit Realty, Vaporwave, backrooms, weirdcore and other landscapes beyond the threshold.« Nero Books & Aksioma, 35-42.

- Tiqqun, (2012). Preliminary materials for a theory of the young-girl.« MIT Press.

Artist: freštreš, Dasha Ilina, Rok Kranjc, Pablo Somonte Ruano, Alice Strete & Simon Browne, Undoing.Studio, Xcessive Aesthetics, Inari Wishiki

Exhibition Title: MFRU30: Off the Shelf. Post-Consumerist Imageries When the Business Left the Building

Curated by: Davide Bevilacqua, Lara Mejač

Place (Country/Location): Maribor, Slovenia

Dates: 18.–27.10.2024

Photos: Photos by Valerija Intihar and Mitja Lorenčič. Images courtesy of MKC Maribor.