Kateryna Volochniuk

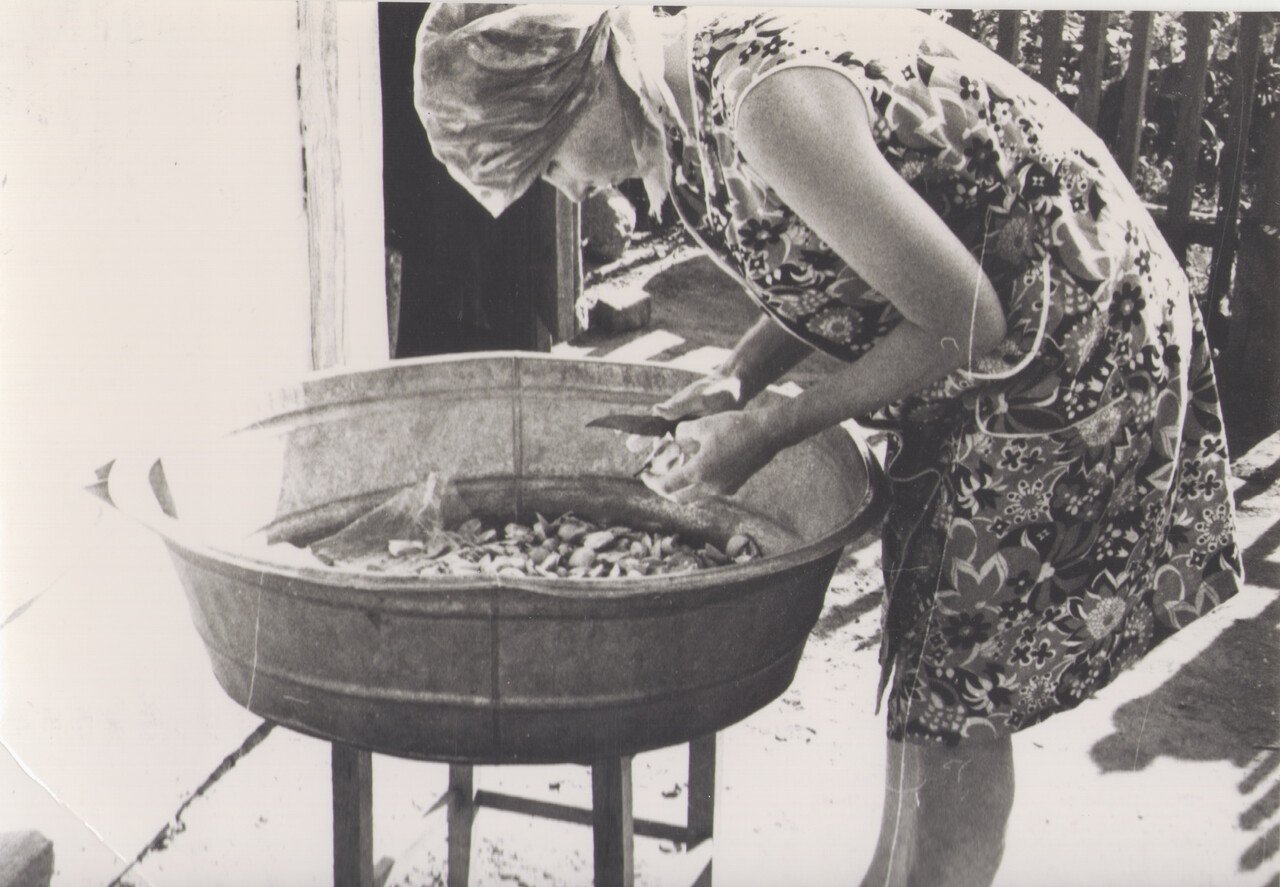

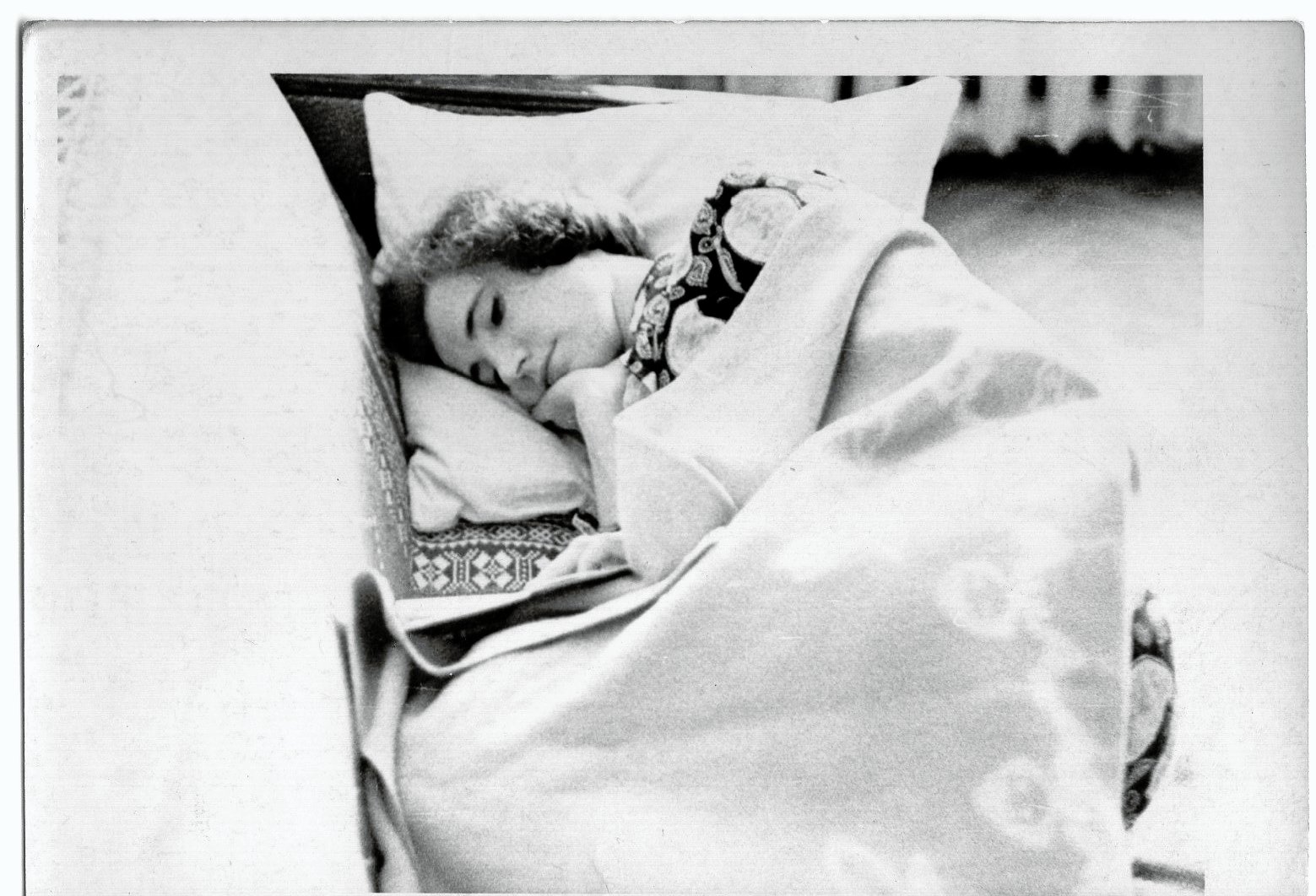

This photograph of my grandmother, Valentyna Shepeliuk, taken by her husband Oleksii Shepeliuk, stands out as one of my favourite pieces in our family archive. This collection spans various generations, from the beginning of the 20th century to the 2010s, with the biggest concentration coming from the Soviet times of the 1960s and 1970s. Unlike the predominant genre of socialist realism of that era, this photograph reveals an intimate space, capturing the subtle routines of everyday life. My grandfather frequently photographed my grandmother during her daily interactions with the mirror: applying makeup, brushing her hair, or simply gazing at her reflection. These images have always resonated deeply with me, offering a window into their relationship.

The relationship between my grandparents is not the sole reason why I find revisiting photographs of my grandmother particularly poignant. During my early childhood, she was a primary school teacher, always restrained and considerate. Our house was frequently filled with her pupils, accompanied by cakes and tea ceremonies in the living room. However, due to her illness later in my childhood, she was unable to maintain the active life she once led. Thus, the family archive became the primary means through which I could trace back her personality and remember her vibrancy. It served as a portal, revealing a diversity of versions of my grandmother Valentyna Shepeliuk — a mother, wife, worker, and a young, joyful woman. The early death of my grandfather at the age of 67, and my grandmother’s illness, marked a turning point in my engagement with our family archive, first as a curious child and later as an academic researcher. This drive was fueled by the gap that was created by the absence of these two significant figures in my life.

When discussing family archives, people often imagine boxes of photographs and albums. However, it was always challenging for me to delineate the actual contents of our archive. I always understood the room in our flat in Kyiv, where my grandmother resided until she died in 2019, to be an archive. This room was filled with the remains of familial activities, mainly those of my grandfather, Oleksii Shepeliuk. Oleksii passed away when I was a young child, leaving my memories of him fragmented and brief, despite his significant presence during my early years. One of my most vivid memories is of him photographing me during our walks together.

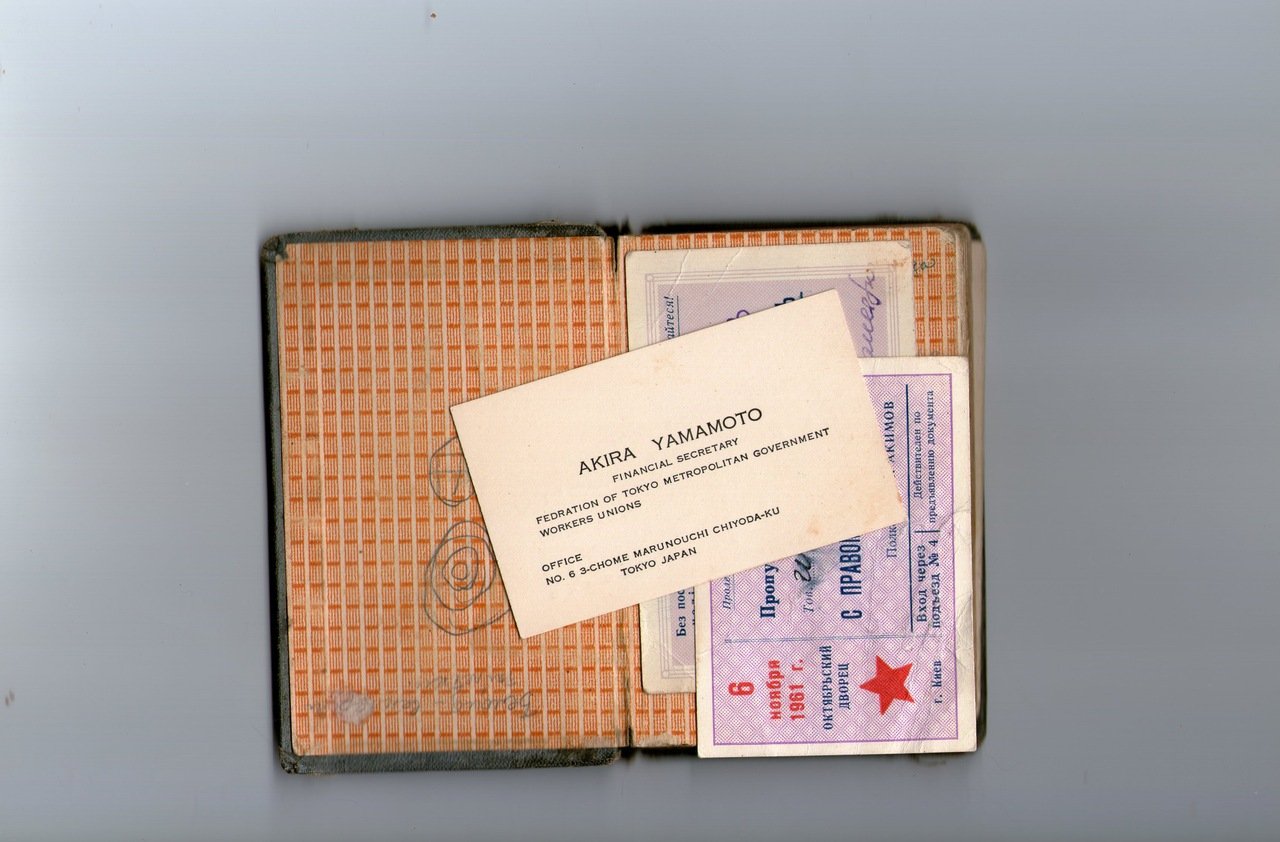

Oleksii worked as a photographer, journalist, and editor for most of his life, so half of grandma’s room was occupied by several giant bookcases that stored a variety of books that he collected. These materials were my first step toward understanding my grandfather’s interests and professional practices. Among them were publications on traditional Ukrainian folk sayings, world literature, dictionaries, and numerous Soviet publications like the Great Soviet Encyclopedias. This exploration was not just an encounter with the image of my grandfather but also with the era he lived in, which is an era largely criticised in my generation – those of us born at the end of the 90s. In addition to books, there were numerous objects: school albums of my mother and uncle, party membership cards of my grandparents, their notes and letters, and Oleksii’s printed university thesis, entitled Photo-Reportage as a Sharp Propaganda Weapon. And, of course, there were several boxes filled with more than 500 photographs taken by Oleksii and other family members.

Oleksii’s collection, which constitutes a semi-personal, semi-official archive,[1] includes objects that represent our familial identity, such as several boxes of personal as well as orphan photographs – those with unknown provenance – spanning different periods, depicting family members and friends in Kyiv, photographs sent to the family as mementoes, and various letters between Oleksii and Valentyna. On the other hand, a substantial portion of this archive can be classified as an official archive, comprising materials that chronicle Oleksii’s professional life and career as a photographer. While examining photographs of my family members and the intimate moments of their lives like weddings and celebrations with friends, I occasionally experienced a sense of discomfort. This collection of images illustrates a past that was already painful and problematic for my generation back in the 2010s. Even as a teenager, I knew that I could not separate these ordinary family events from the larger socio-political climate. I was already aware of the Holodomor, Russification policies, forced deportations, and so on. Consequently, the communist project was highly discredited in the eyes of the younger generation, along with the people who were part of this system. It is essential to recognise that a family archive extends beyond merely recounting the stories of those dear to us and their immediate realities. Okwui Enwezor posits that “(…) domestic photography allows us to see the archive as a site where society and its habits are given shape”[2]. In addition to its personal value, Oleksii’s archive depicts Ukraine’s industrial legacy, and embodies the dissonant heritage that existed within the Soviet era.

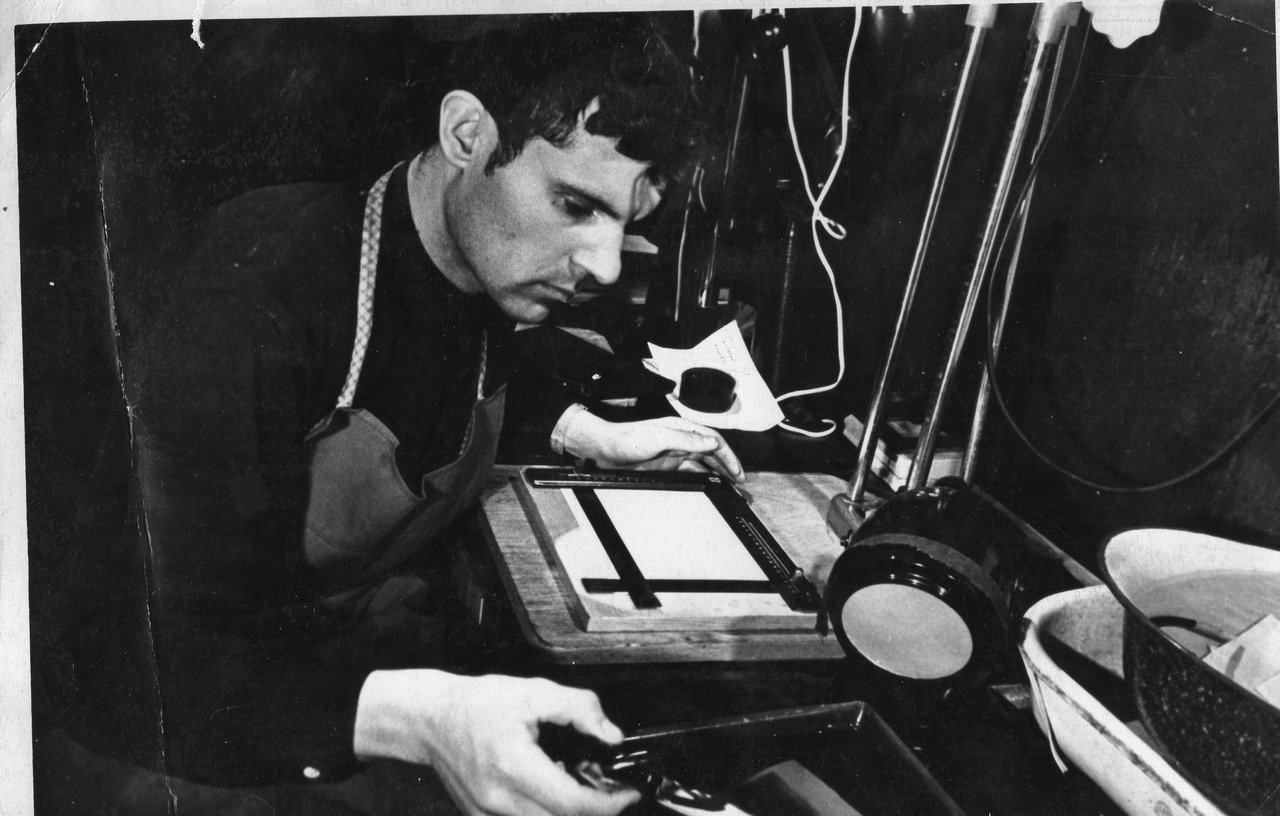

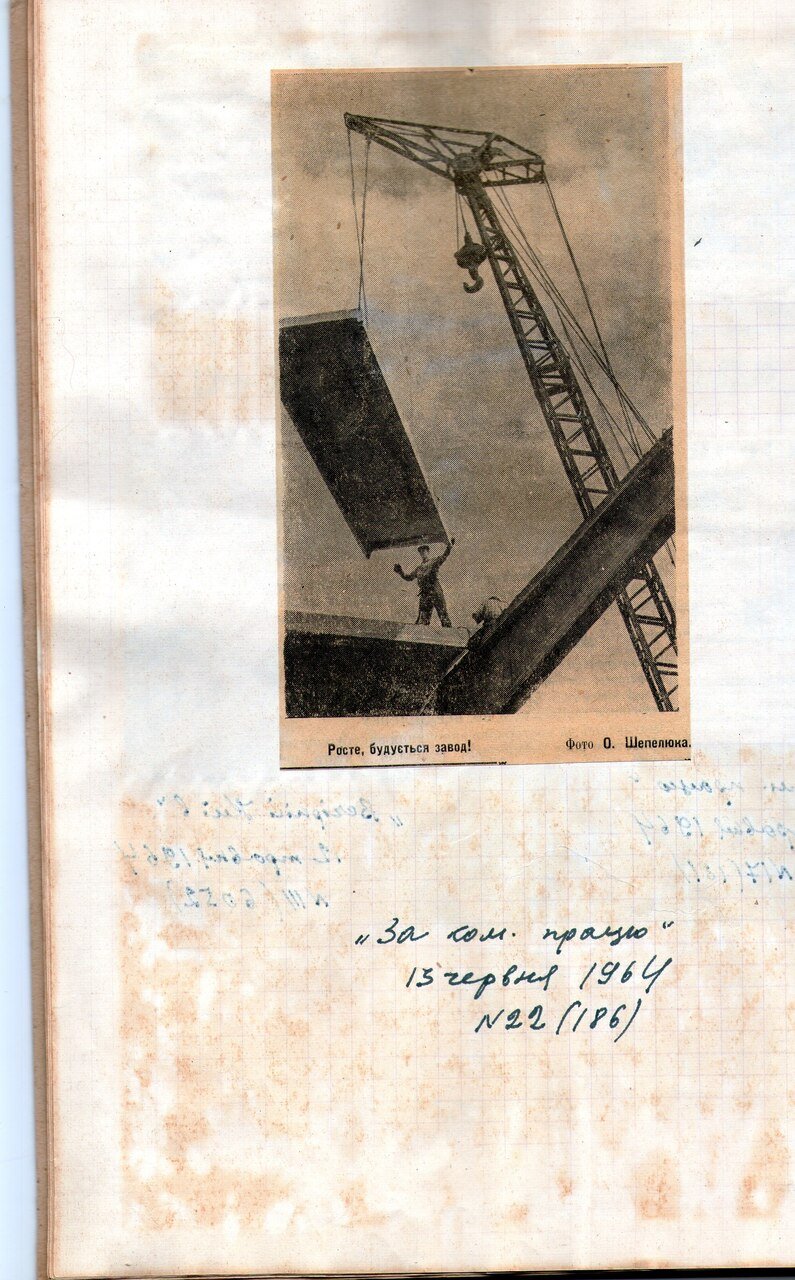

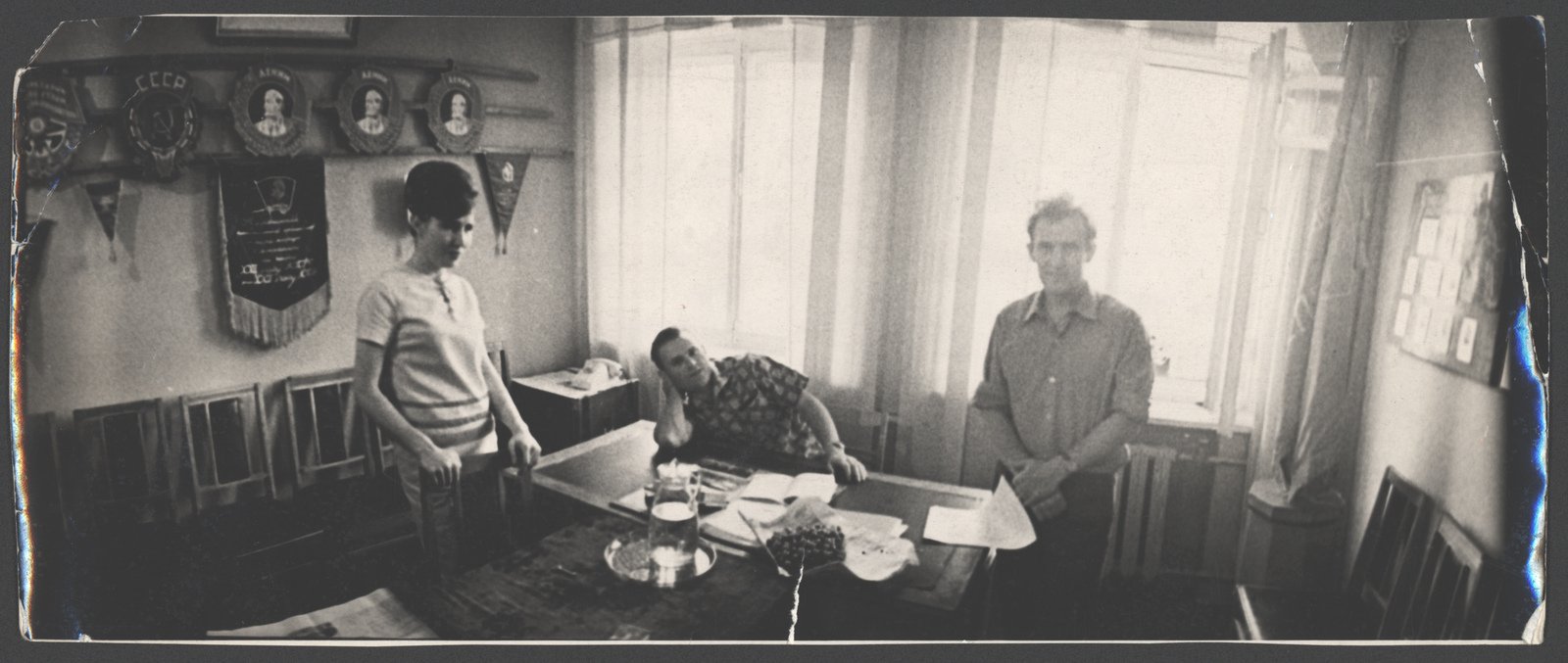

Even though he worked in various places throughout his life, such as Newsreel Studio and the daily newspaper Evening Kyiv, most of his preserved documentation is related to one specific place. From 1963 – 1970, Oleksii worked as a photographer and editor for the Kyiv Lepse Factory newspaper. The Kyiv Lepse Factory, primarily known for producing agricultural machinery such as tractors, was also integrated into the larger military-industrial complex typical of Soviet-era factories. Related to this work we can find his employment record book and a notebook detailing his experiences at the factory. This notebook served as a draft for Oleksii’s final chapter in his thesis, entitled “From My Personal Experience.” In it, he sheds light on the daily routines of photographers at the factory, describing some favourite techniques for shooting his subjects and revealing the inner workings of the editorial team. There is also a notebook with excerpts of his articles and photographs published in the factory’s newspaper. These elements help highlight the broader implications of individual agency within state-imposed frameworks, illustrating how personal and professional lives intersect in complex ways.

Factory newspapers played a crucial role within this industrial ecosystem, functioning both as a communication tool for the extensive factory community and as an instrument for worker control and discipline. In this context, photographers and editors emerged as pivotal figures, shaping the production of images and narratives that, while less visible than the machinery infrastructure, were integral to the industrial production process. This dual role underscores the importance of their work in maintaining the ideological and operational coherence of the factory environment. Excerpts from the factory newspaper featuring “restless” workers, slogans promoting communist labour, and meticulously filled party membership cards noting all attended sessions filled the pages, as well as inescapable symbols of Soviet power such as images of posters, busts, or signs with the visage of leaders. There is also a predominance of “photo-accusation” – a practice that involved photographers documenting working violations like improper storage or misuse of machinery. These photographs would then be published in the newspaper as a means of disciplining the guilty worker and exerting state control. This everyday surveillance was crucial in a hermeneutic workers’ society, where each individual was aware of both their own performative role and that of the others. Was Oleksii genuinely naive enough to believe in this ideology? Was he truly passionate about it, or was he merely engaging in it performatively, playing his role while pursuing other interests behind the scenes? These questions are particularly pressing now as the Ukrainian community confronts our collective past, decolonising it during active war. Reflecting on these challenges, I have decided to situate Oleksii’s practice within the power structures of Soviet colonialism, emphasising a methodological shift from vertical models of power to something more horizontal, focusing on the importance of individual agency and everyday experiences within this system. This approach allows me to view people not merely as victims but as active agents in shaping history.

After my grandfather died in 2004, my uncle, Oleksii’s son, who shared an interest in photographic practices, transported parts of Shepeliuk’s archive to his home in Donetsk. At the same time, the other half of the archive remained in my mother’s flat in Kyiv. This marked the beginning of the archive’s displacement. Parts of the archive were then further displaced during the Russian occupation of Donetsk which began in 2014. The arrival of Russia-backed forces and the subsequent seizure of the city led to the looting of two houses where my uncle’s family had been living, which is also where Oleksii’s archival materials were stored. The fate of the looted materials remains unknown, and the list of losses includes up to six cameras, numerous lenses, journals, and laboratory equipment, all connected to Shepeliuk’s journalistic career. Before the full-scale invasion, I curated a selection of photographs that were kept in my mother’s flat along with some of my grandfather’s notes and his university thesis. I relocated them to my own apartment, both for research purposes and as mementoes. With the full-scale escalation of the war in February 2022, these elements were displaced along with me to Scotland. Consequently, the archive has become deeply fragmented across different locations by various family members and strangers alike.

In Ukraine, my homeland, the onset of Russian aggression and occupation in 2014 catalysed a phenomenon termed “archive fever.” This concept, developed by Derrida, captures the intense passion for uncovering and reclaiming lost artefacts of our past[3]. Ariella Azoulay, engaging with Derrida’s ideas, states that archive fever is not solely a fixation on the past but an active desire to engage with the present[4]. Azoulay argues that archives are not passive repositories of historical records; rather, they embody our collective history and are inherently designed to facilitate its dissemination[5]. In this sense, archives function as active participants in the historical process, encouraging individuals to seek agency in reshaping, reinterpreting, and reconstructing narratives. This perspective gains particular relevance during wartime, especially with the example of Ukraine, where individuals are confronting their postcolonial status and striving to assert agency within the historical discourse. Understanding the powers and limitations of archives is crucial for survival in these catastrophic times and for engaging with our past, present, and future.

Several Ukrainian and international initiatives – state-sponsored, institutional, and grassroot – have emerged over the past decade in response to Russia’s war. There is INDEX: Institute for Documentation and Exchange (Lviv)[6], Mariupol Memory Park[7], The Wartime Art Archive by UMCA[8], the Ukrainian Archive[9], the Ukraine War Archive[10], the Urban Media Archive by the Lviv Center for Urban History[11], the Queer War Archive[12], and many others. These initiatives reflect a broader effort to seek justice for the present and future through the process of deoccupation. The legitimisation of events through their inclusion in an archive fulfills the archive’s role as an evidentiary mechanism, ensuring that such experiences are recognised and preserved. But the effort to render certain aspects of individual, daily life archivable — such as familial legacies, memories, practices, and experiences — remains a struggle. How do these legacies become integrated into the epistemic framework of what is deemed worthy of preservation? A bright example is the project After Silence[13]. This initiative employs several tools, such as oral history and fieldwork, to record and preserve community memories about traumatic topics like Ukrainian forced labour in Germany and Soviet mass deportations. As described on their website: “Officially ignored stories are kept in silence: in family misunderstandings, on the pages of photo albums, in unrecognizable landscapes[14].”

This archival shift also represents an act of reclaiming knowledge that has been accumulated in these repositories, calling to mind the well-known phrase, “nothing about us without us”[15]. To this point, archives have increasingly come under scrutiny by the Ukrainian cultural community, reflecting their growing significance in the public eye. As new initiatives emerge and innovative methods of engaging with archival material are developed, concerns about the inherent characteristics of archives – particularly their selective nature – become more pronounced. What will be included in the archives of the future, and what will be silently omitted? Maria Vtorushina addresses these questions in their text Queer and Death in Ukrainian Art Archives of Wartime, written in dialogue with the Wartime Art Archive by the Ukrainian Museum of Contemporary Art[16]. Vtorushina examines the experiences of queer artists during wartime and their attempts to document these experiences through various archival practices, questioning whether these efforts will be recognised in the official wartime art archive or if they will remain marginalised. This dialogue is crucial as it highlights the inherent biases in archival practices and the persistent need to critically evaluate what is deemed worthy of preservation.

As my archive deals with familial and state legacy, numerous ethical questions are raised, particularly concerning the issue of selectivity. Did Oleksii desire this collection to be preserved and presented as a public archive? Was he documenting these moments with the future in mind? What narratives might he have offered if he had been able to express his opinions freely? When considering the photo archive, it is also helpful to think about the intended audience of these images and whether the individuals depicted had the opportunity to engage with them. While this distinction may be evident in the case of a family archive, the semi-official archive presents different considerations. As a repository maintained by an official photographer, it prompts questions regarding the role of ordinary workers in the production of cultural imagery within their workplace. Were they merely depicted as models for disciplinary surveillance and performative representations of idealised worker lives? Or, perhaps more importantly, were they represented in the way they wanted to be?

As one of the custodians of our family archive, for me these questions are ever-present. It has also become essential to consider the location of my family archive, its preservation methods, its accessibility to other family members, and the inclusion of other family members’ narratives within Oleksii’s collection. Ongoing collaborative engagement of all family members with the archive ensures its comprehensive and contextual integrity. And as well, it is important to note that objects do not necessarily have to be physically present in the archive to convey information; gaps and lacunae within the archive also produce significant traces and insights. The challenge lies in representing these voids digitally — how do we depict looted or destroyed objects or places and the empty spaces they leave behind?

With the rise of the internet as a tool, many traditional physical archives have been transitioned into the digital realm. This shift online has been accelerated by the wartime experience, which has led to the displacement and/or digitisation of numerous archives. While this transformation has led to the development of innovative practical techniques for preserving cultural heritage and enhancing its visibility, it also prompts an intriguing inquiry into the power dynamics of these artefacts and repositories: are they being stripped of their original context, and how do they retain their capacity for engagement?

Over the past decade, the evolving archival attitudes and practices that have emerged in Ukraine exemplify a shift towards innovative and critical approaches, as we actively seek to assert our agency in shaping a collective future. And as I delve into my family archive, I see my grandfather, my family, and the complex collective of factory workers. I see how their daily lives were influenced by their surroundings and the small community that formed around these industrial sites. Simultaneously, I also see evidence of the violent Soviet regime, Russification, and extractivism. I don’t know what fate is destined for these remnants, but I want the people who’ve been touched by them to be in charge of that trajectory.

Kateryna Volochniuk is a Ukraine-born, Scotland-based art historian and researcher; she is a SGSAH-funded PhD Сandidate at the University of St Andrews and is a Researcher at The New Centre for Research & Practice. She currently holds the position of Visiting Doctoral Researcher at the Lviv Center for Urban History. Volochniuk’s scholarly pursuits focus on the intersection of the history of photography and memory studies. Her ongoing research project delves into the personal archive of her grandfather, within which she explores modes of documentary in Soviet photojournalism and analyses cultural production within industrial archaeology.

This text is one of four commissioned for Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow, a project implemented by Fundacja Ziemniaki i and Stroboskop Art Space (Warsaw) covering themes related to the production, dissemination, and evolution of contemporary Ukrainian art and culture during active wartime circumstances. Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow is supported by IZOLYATSIA foundation, Trans Europe Halles, and Malý Berlín, and is co-financed by the ZMINA: Rebuilding program, created with the support of the European Union under a dedicated call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced people and the Ukrainian Cultural and Creative Sectors.

[1] By “personal”, I mean a collection created by a single collector or family that depicts their close family and friends; by “official”, I mean a public collection that portrays a collective public history, which can also be used as an administrative tool.

[2] Enwezor, Okwui. 2008. Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art. Edited by Okwui Enwezor. N.p.: International Center of Photography.p.40

[3] Jacques Derrida and Eric Prenowitz, ‘Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression’, Diacritics 25, no. 2 (1995): 9–63, https://doi.org/10.2307/465144.

[4] Ariella Azoulay, ’Archive’, Political Concepts: A Critical Lexicon, July 21, 2017, https://www.politicalconcepts.org/archive-ariella-azoulay/.

[5] Azoulay, ’Archive’.

[6] INDEX: Institute for Documentation and Exchange: https://www.index-ukraine.org/

[7] Mariupol Memory Park: https://www.mariupolmemorypark.space/

[8] The Wartime Art Archive by UMCA: https://waa.umca.art/en

[9] Ukrainian Archive: https://ukrainianarchive.org/

[10] Ukraine War Archive: https://ukrainewararchive.org/eng/

[11] Urban Media Archive: https://uma.lvivcenter.org/en

[12] Queer War Archive: https://queerwararchive.com/

[13] After Silence: https://aftersilence.co/main-page/

[14] After Silence, main page.

[15] ‘Nothing about us without us’ is a phrase that originated in the disability rights movement and later became widely popularised as a call for people to participate in the planning of policies that affect their lives: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/iddp2004.htm.

[16] Maria Vtorushina ‘Квір і смерть в українських мистецьких архівах воєнного часу’ [Queer and Death in Ukrainian Art Archives of Wartime], Krytyka, June 2024.

https://krytyka.com/ua/articles/kvir-i-smert-v-ukrainskykh-mystetskykh-arkhivakh-voiennoho-chasu