Piotr Sikora

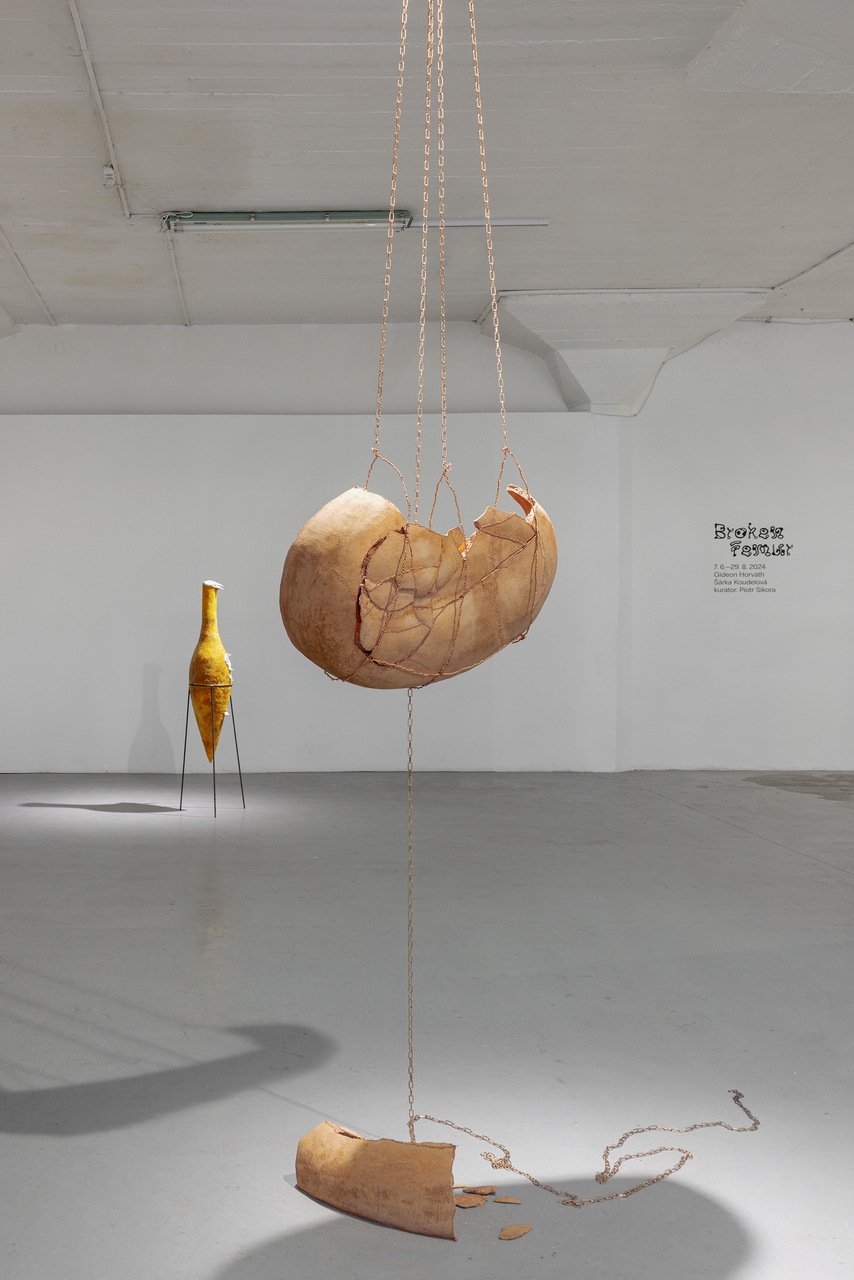

The conversation between artists Šárka Koudelová, Gideon Horváth, and curator Piotr Sikora took place on the 26th of April 2024 in connection with Broken Femur at Pragovka Gallery in Prague.

When anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978) was asked by students what she considered to be the first sign of civilization, they expected her to talk about clay pots, simple hunting tools, or religious amulets. But no – Mead replied that the first evidence of civilization was the discovery of a 15,000-year-old broken human femur bone that had been healed.

In nature, if you break your leg, you die. You can’t run from danger, you can’t get to sources of water or hunt for food. And no creature survives without compassion and help long enough for a broken femur to heal. Civilization begins at the moment when a second being helps the injured one and takes care of it, instead of abandoning it to preserve its own life or comfort.

We understand the theme of this exhibition as a call for a change in social dogmas, to finally grow out of learned prejudices and behavioral patterns. It is an opportunity for unlearning, a chance to rewind the entire prejudiced process, to decolonize our thinking from a normative, binary, polarized view of the world and find completely new starting points.

The installation of the exhibition is surrounded by a material environment that allows visitors to interactively intervene and change its shape. It is also a meditative corner that invites haptic experiences, it is a return to ancient methods and natural materials. It consists of almost alchemically contrasting substances of wax and sand, which create an atmosphere of subliminal tension and polarized qualities that need to be stirred.

We hear in it a call, “Let’s break our collective femur!” Let’s start again; break the femur of this society and together, take care of each other and patiently wait for it to heal. Let’s unlearn dysfunctional, colonizing patterns based on power strategies and cultivate new, intuitive visions. We need collective solidarity, connected to our physical and emotional wisdom.

Piotr Sikora: Is failure, mistake, or malfunction part of your art in any way? I’m thinking about practical things but also theoretical assumptions. What happens when you make a mistake?

Šárka Koudelová: I often come across the opinion that my art is very well-planned and almost mathematically calculated. It’s not true. However, I certainly have a lot of control over my creative methods, even though I invented them to resemble natural processes. In my second year at the academy I started to paint my collection of minerals, which I have had since childhood. I felt stuck and didn’t know what to do. These layers formally came from this moment when I was trying to imitate geological processes. It was satisfying that I found a way to record time in my paintings.

PS: So what is the failure you are afraid of? Is it a technical failure or something else?

ŠK: I don’t know – that’s the question. Maybe I fear that my works won’t be authentic to their original emotion. I’m worried that I will look back and realize this wasn’t what I wanted to achieve. Whenever I try to incorporate something more expressive into my work, I fail. One time when I allowed myself to fail and be expressive was when we made a series of paintings with my son. I let him draw and paint with me, and eventually, I created these marble windows around his sketches, which was therapeutic. Those are symbolic images of parenting to me – creating a frame, a protection, a window, for my child.

PS: Gideon, how about you? How about failure? Because in your case it’s even more delicate when it comes to the wax matter you are working with.

Gideon Horváth: In my case, I have to accept that I won’t be able to immortalize my work in the usual artistic sense. The material has its agency. Even after you are done with the piece, you cannot be sure how it will change with time. When I started working with wax I felt that I was not an omnipotent artist. If I don’t like the work, even if I like it but don’t want to keep it, I can melt it and create a new work with the same material. This fact was freeing because when I started working with it, I had never studied sculpting and it was a completely autodidactic journey, and still is.

Regarding failure, I think there is a huge pressure on many artists that you have to produce immaculate masterpieces all the time. If something is not living up to that standard then you shouldn’t show it to the public. I think that’s such a problematic way of thinking. When I look back at what I’ve exhibited in the last years, I see this journey from A to B to C. It was a completely public story of imperfection, struggle, getting it right, and then failing and trying again. Everyone wants to be successful, but I think success in many ways is boring. Failure is much more exciting and interesting. It’s such a complicated and dark and ambivalent notion. There is a book by Jack Halberstam called The Queer Art of Failure, which is very important to me. Halberstam, a transgender philosopher, writes about how you can criticize the heteronormative, capitalist, patriarchal society with failure. Instead of committing to success, you highlight the process that is often based on failure. To me, it is an amazing way to hijack the progress-oriented system and make it more flexible. I’m inspired by that.

PS: Still, in order to be able to share your mistakes you need to have some kind of exposure, so in the end, visibility is already a success. Allowing yourself to fail is some kind of privilege.

GH: Certainly. Then we enter the topic of authenticity. When you fail and you are not afraid of it, it allows you to keep on going. However when you fail to be truly authentic, that’s a different thing for me. It is important not to blindly follow certain expectations and to remain true to the artistic process. As for the topic of success in our field of work, speaking for myself, I’m still negotiating the meaning and cost of success especially since it is still something relatively new for me.

ŠK: But could you specify what you understand as success? Is it about visibility, or recognition?

GH: For me, one of its aspects is the privilege to be able to make your work visible, to be able to sell your works and make money from your art instead of having several jobs on the side. It is also a fragile place to be because we are always scared that it is going to change, that it won’t last.

ŠK: I think this is extremely personal. Not to mention in the era of social media, it’s easy to create the appearance of success when you are barely hanging on. It happened to me several times that people, young female artists especially, approached me with compliments on how I manage my art career while being a mother and working as a curator. I want to say it’s not true – it’s Instagram. Of course I don’t post all of the chaotic moments from my home, how messy everything is, all the night shifts. I feel the responsibility to say it’s not as bright as it might seem. It’s not easy, and frankly sometimes it’s terrible. There’s a huge misunderstanding in the post-capitalistic way we understand success.

GH: That’s why we should call for breaking the femur – for leaving the paradigm, to be able to relearn the notion of success and failure.

PS: Have you ever broken anything?

ŠK: I think I broke my hand twice, both of my hands actually. One time it was my left hand and then it was my right hand. I was little, like between eight and twelve or something like that. But nothing else.

PS: Was it traumatic? Do you still have memory of the pain and healing process?

ŠK: In both cases it came by surprise. The first time I was dancing; we were having a fire in some friend’s garden. It was dark and I fell and broke the bone. The day after, we were traveling with my mom and my sisters, it was super hot and it started to hurt during the journey. It was very adventurous. We had to find somebody with a car to take us to the hospital. Then we found out I had broken it, and they put it in a cast. It was in the middle of summer and I was not allowed to swim. The second time it was winter and we were playing in the snow with my sister and some friends and we had a sled crash. She fell on me and I broke the bone in my hand. It was during the Christmas holiday and we had a lot of tasks to do from school. Thankfully I was liberated from that.

PS: Gideon, did you ever break anything?

GH: My heart (laughter). Not really. I dislocated my shoulders several times and they both are still fragile, so they should be operated on, which I’m not a big fan of. Once I dislocated my right shoulder and it was extremely painful because normally it just pops back into place. But that time it was out and higher up. I had to lean against the wall to keep it in place. I waited almost 2 hours for the ambulance. I was crying, the pain was so awful. The ambulance couldn’t get to the street because of Erdogan’s visit to Budapest. Since then, I have dislocated my arm again this year. I’ve been attending physiotherapy ever since. I enjoy these sessions when they touch in a very delicate way and it hurts so much that you clench your teeth and grab the bed. I started to learn to accept the pain. To be aware that the pain is coming and try to disassociate from it and just look at it like this strange, puzzling phenomenon. Not to be so alarmed, not to panic, but to accept that it’s going to hurt and it’s fine, it’s not a bad thing.

PS: And when you dislocated your arm recently, did some memories from the first dislocation hit you?

GH: The first time I dislocated it I was in school. I was twelve years old. It happened during a basketball game. I was very tall already and I jumped. It was me jumping up for the ball at the start of the game. The force of catching the ball at the same time just dislocated my shoulder. The last time it happened, it was one of those strange winter days when rain freezes on the ground. I fell on my shoulder and I just heard it crack and I felt this immense pain, but I wasn’t sure what happened, so I stood up. This lady was walking her dog and she was asking me if I was all right, and I didn’t know what to answer her. I felt this urge to reassure her that I was okay even though I was not sure if actually I was. That’s a recurring thing – that I want to reassure myself and the people around me that I am fine when in fact I don’t know if I’m fine.

PS: Yeah, I know this feeling. Instead of taking a moment for yourself you are instantly trying to please others or not to make a scene.

GH: I’m afraid of falling in general. Maybe because I’m so tall. When I do fall, and I don’t know if I’m hurt, the best thing would be to just take a moment to lay there.

PS: Yes!

ŠK: Speaking about this kind of strange need to reassure everyone around that you are fine – I have a strong memory connected to an injury. It was not breaking bones, but it was kind of similar because when I was 14, I had a brain concussion. I fainted for 20 minutes. The first thing I can remember is that I was saying, “It’s fine, it’s fine” multiple times because I didn’t realize that I just said that. The people around me were asking me not to repeat it as they could see that the situation was kind of dramatic. Eventually I was taken to the hospital. I do remember this feeling – wanting to reassure everyone that I was fine. I’m asking myself why, when something bad happens to you, the first thought is to calm everybody else around you down?

GH: Both of you have kids, and I’m just wondering whether this notion is linked to the fact that as a kid you are often being calmed down whenever something happens to you.

PS: You are right. I think it’s important to make the kid aware that you are actually interested in the source of their cries or pain. When something bad happens to my sons, I try to acknowledge it rather than patronize it. To address it and recognize it.

ŠK: I agree. It is crucial to allow your children to cry and to feel bad – to create a space for those feelings and to know that it is fine to feel them.

GH: Maybe that’s a generational thing as well. Our parents are the “It’s okay, don’t worry about it, it’s going to be fine” generation. The optimistic nineties parents. As we are living with the crisis, we are more used to saying “it hurts, it hurts, it’s okay, it hurts.”

PS: In what way can your art be part of the healing process? And why do you think art, in particular, takes on this role related to recovery, healing, and mending?

ŠK: It’s still surprising, even to myself, that I believe art has the capacity to make a change. But on the other hand, I’m very skeptical about the effectiveness of the contemporary art scene. I’m wondering whether it’s possible to think of the healing process as something psychosomatic or rather metaphorical.

PS: Should art be about making you feel better – which is already some kind of a healing process? Or should it rather push you toward this conundrum of problems?

ŠK: I believe it’s somehow connected. Sometimes you choose to be gentle and caring, and other times you need to be very pushy, critical, or even unpleasant. I think art can do both. Not just art, but also the scene it represents. The whole process of making exhibitions relies on the fact that you are caring, gentle, and full of empathy. For me, and I guess also for Gideon, it is very much connected with the formal side of exhibitions and artworks. On the other side, I also believe that when the moment arises, you have to be expressive and radical – that’s what we were referring to when speaking of “breaking the collective femur” in our statement. When gentle methods fail and there is no space for diplomacy, it’s better to break something and allow it to heal.

PS: But don’t you think something like that already happened in 2020? The pandemic was like a bone breaker. For me, the very idea of degrowth was fostered throughout this period. Even though things went back to “normal”, if they didn’t get worse… the fact that we are deliberating themes such as degrowth, a change of the paradigm, and solutions to other crises, I find positive.

GH: I don’t think an exhibition can take up a whole societal problem or crisis. But a breaking of the bone is exciting in a metaphorical sense. When I think of the healing power of art, I think of all of those artworks that I encountered throughout my life that were liberating, cathartic, and euphoric. But the artworks that have had the longest-lasting effect on me were not necessarily pleasing or evoking good feelings. Those were often bold and “bad” pieces that, in a way, hurt me. As we are speaking about healing and care, I would like to address the psychological side of these processes. What is thrilling for me in art is that I can recognize a feeling or an emotion that I experienced in my childhood, a very long time ago, and connect it with an emotion in the present. The connecting element would be art – Tarkovsky’s films or Bacon’s paintings – that I saw many years ago. In his case, it was hard to look at his paintings of his lover, hard and liberating at the same time. It was healing in that way that you look pain directly in the eyes and then move on. So I think that for me, breaking the bone, in a way, is being able to experience pain and then also experience the joy of resilience, the joy of survival, that comes afterward.

PS: So I guess it’s not about breaking one massive femur, but many small ones?

Within this text we have also included a few images from a performative lecture that was held with anthropologist Martin Soukup on the premises of Pragovka Gallery on 18.07.2024, in the context of the exhibition Broken Femur. About the lecture:

There is a recurring moment in our exhibition when the body, its parts, products or even its remains, are used for recovery, provide shelter or become a means of healing rituals. The provision of one’s own body, that is the transformation of an essential part of our existence, identity and survival into an object that serves, cares and heals, is seen as a symbol of the moment around which Margaret Mead’s mythical statement revolves. The sharing of one’s own necessary resources, putting oneself in danger and scarcity, and the care itself, indeed sounds like the beginning of human civilization. But how was it with her quote in reality?

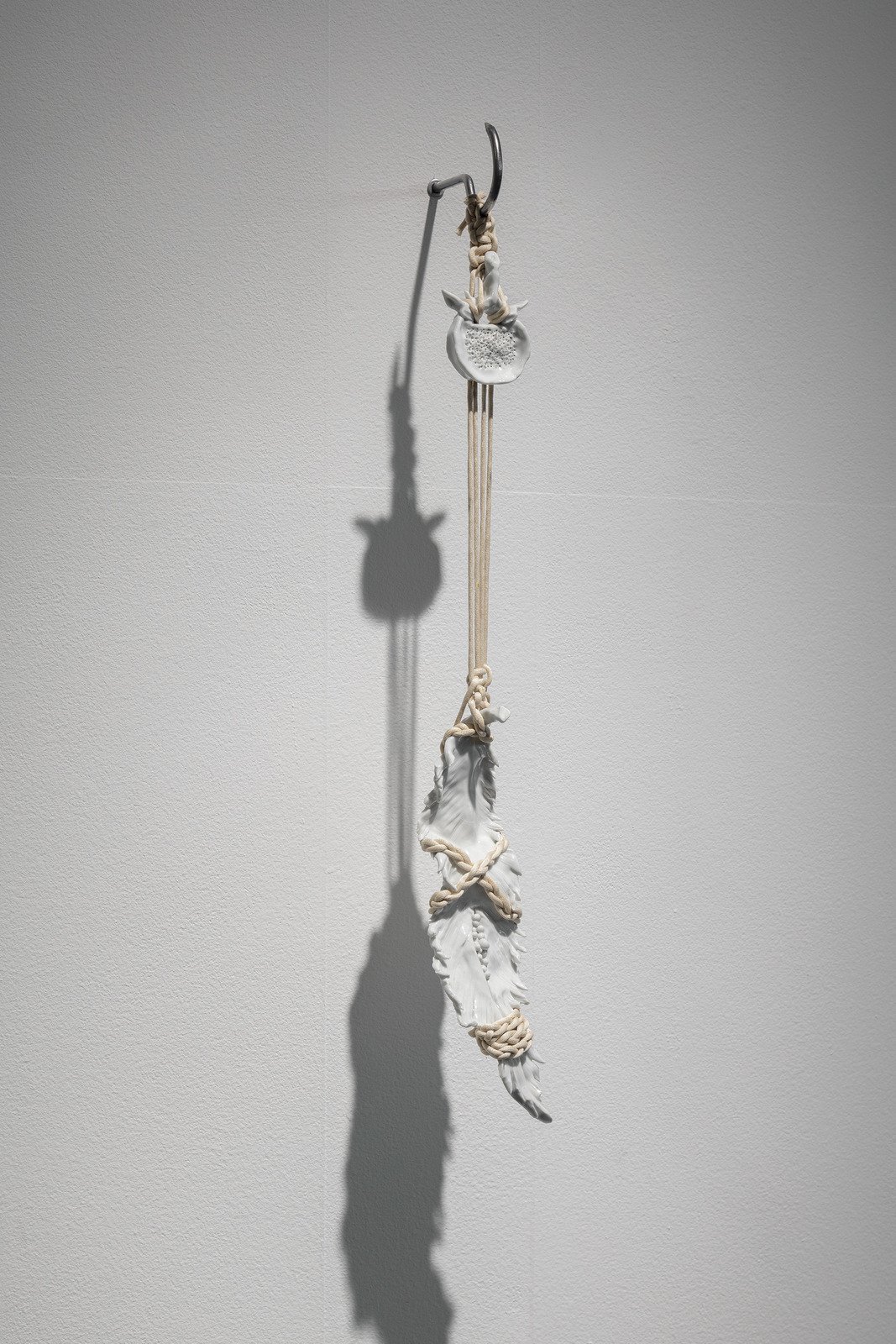

Gideon Horváth (1990) is a Budapest-based visual artist. He studied performing arts and cinema at Université Paris VIII. (2010-2013) and intermedia at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts (2014-2015). In 2023, he was awarded the Esterházy Prize, and in 2024, for “Myths of Vulnerability,” he was awarded the prize for the best solo exhibition of 2023 by the Hungarian branch of the International Association of Art Critics, AICA. He has participated in residencies at PRÁM Studio in Prague, Czech Republic (2023), Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart, Germany (2012) and Cité International des Arts in Paris, France (2020). His work has been featured in many solo exhibitions – including “Memory That Could Have Been” at Sidewalk (as part of the First Biennial of Contemporary Public Art in Budapest, 2023); “Pulp” at Pram Studio (Prague, 2023); “Myths of Vulnerability” at Glassyard Gallery (Budapest, 2023); “Kiss of the Sun” at Ena Viewing Space (Budapest, 2022); “The Faun’s Ball” at TIC Gallery (Brno, 2021); “Faun Realness” at ISBN Gallery (Budapest, 2021); – as well as group shows – among others “Esterházy Art Award Short List” at Ludwig Museum (Budapest, 2024), “…and they lived…” at Kunsthalle Bratislava (Bratislava, 2023); ; “The Sea of Cheese” at TRAFO (Szczecin 2023) “Different Solar settings” at David Kovats Gallery (London, 2022); “Sensory Tales” at Krinzinger Gallery (Vienna, 2022); “They/Them/Their: Naturally Not Binary” at IMT Gallery (London, 2022) and “Hope is not Desire” at Sopa Gallery (Kosice, 2022).

Šárka Koudelová (1987) studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in the studios of Graphics II, Drawing, and in 2016, graduated in the Painting II studio under doc. Vladimír Skrepl. In 2015, she completed an internship at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

The fundamental theme of her creative process is exploring the relationship between humans and the passage of time. Through historical and material references in her paintings, objects, and installations, she addresses forms of social injustice, such as colonial thinking, the patriarchal system, the climate crisis, and recently, motherhood. In recent years, she has exhibited in places like Karlin Studios in Prague, Guna Contemporary on the Greek island of Kastellorizo, Fait Gallery in Brno, Zahorian Van Espen Gallery in both Prague and Bratislava, Salon Goldschlag in Vienna, and Sonneundsolche in Düsseldorf. Šárka Koudelová often combines the role of artist and curator, seeking new opportunities for collaboration in the global art scene. From 2012 to 2015, she co-ran the gallery k.art.on in Prague with Ondřej Basjuk. Since 2018, she has been the curator of the international residency program at Studio PRÁM in Prague.

Piotr Sikora (1986) born in Krakow. A critic and curator of contemporary art. In his curatorial practice, he draws inspiration from sauna culture, fried cheese, mycology, and kitsch. He runs artistic residencies at MeetFactory in Prague, raises two sons, and obsessively rides a bicycle.

Artist(s): Gideon Horváth, Šárka Koudelová

Exhibition Title: Broken Femur

Venue: Pragovka Gallery

Place (Country/Location): Prague, Czech Republic

Dates: 07.06. – 29.06. 2024

Curated by: Piotr Sikora

Photos by: Marcel Rozhoň