Kateryna Iakovlenko

І

Let me start with a poem – a poem about a perfect day:

A Perfect Day No. 9

I wake up in the morning,

Quite early, because it’s still very quiet outside.

It’s a little chilly, but warm at home.

Someone offers me something, from the very morning –

Food,

Then drinks,

And so on through the day.

Maybe it’s the same person.

Maybe different ones.

I’m not that hungry,

But it’s so pleasant to be cared for.

It’s very, very pleasant.

The whole day is covered with warmth and care.

And not a single, single, single piece of bad news. Everything is fine. And this doesn’t frighten me, it doesn’t “keep me from relaxing.” Because sometimes it happens – nothing bad occurs, and yet one doesn’t feel well.

Today it’s not like that. There is warmth. Care. And the absence of bad news becomes a young sprout. There’s a clear understanding that tomorrow the absence of bad news will grow. It will strengthen. Perhaps it will even fill everything up.

But today it’s a good sprout.

Someone will turn on unbelievably fitting music.

Something good – unknown to anyone – will happen late at night.

The whole world tonight will sleep, made happy by something unknown, regardless of time zone.

This poem was written by Ukrainian artist Stanislav Turina, whose practice is deeply entwined with what we call human life, and even more so, created from constant thought about the people nearby. It’s about human relations, conversations; the everyday routines, rituals, habits – both good and bad – the ones one doesn’t even deserve, and yet they exist. All that fills the days, which in turn fill weeks, which fill years – an entire life.

This poem describes routine, but has been written at a time when such routine is impossible. Is a perfect day possible during war? If yes – what is it like? At first there was Perfect Day No. 1, then the second, third, fourth… How many in total? Turina always counts precisely. There must be an exact number. But this time he cannot say – he lost track along the way.

There are 365 days in a year. How many days have been erased by the war? And how many people have been lost in this calculation?

Perhaps thoughts of a perfect day during wartime can lead to sadness. But sadness is a sticky material of life’s affairs, as once mentioned by Deborah Vogel – a writer and literary critic of Polish-Ukrainian-Jewish descent. She wrote her texts in Yiddish and Polish, I read her in Ukrainian translation. So now I think, did she really mean sadness or was it something else? Something like melancholy, sorrow, grief, or even fatigue – the last one often used to describe the state of social emotions after days and weeks and now years of war. Yet, still, in my opinion, there is a whole range of unnamed emotions; emotions that are extremely difficult to translate into any language. These feelings arose during one of the days of the full-scale war, among the losses – some which have not yet been lived through, or prepared for in advance… though one cannot really prepare for such a thing, one simply knows it may happen. On one such day, Turina’s poem appeared to me.

Just one more day. It doesn’t have to be a perfect one. Just one more cycle of 24 hours; of being present, of existing, of coping with the emptiness.

I read Turina’s poems about this perfect day and think about mine. What would it be like? I believe that now, such a grotesquely perfect day would be one full of the most basic routines. No sounds of war, no trace of its presence. One must repeat all this several times until it begins to resemble truth – or at least until one begins to believe it. And yet, in this wartime reality – since the first invasion in 2014 and then the full-scale invasion in 2022 – it is clear that war has long since become part of the routine, to such an extent that some try not to react, not to notice; they try to ignore it. Art, on the other hand, strives to remind the human of the existence of the human, of the living. What in life still belongs to life in such human conditions? To not live the war, but to live life – because it will exist even after the war ends.

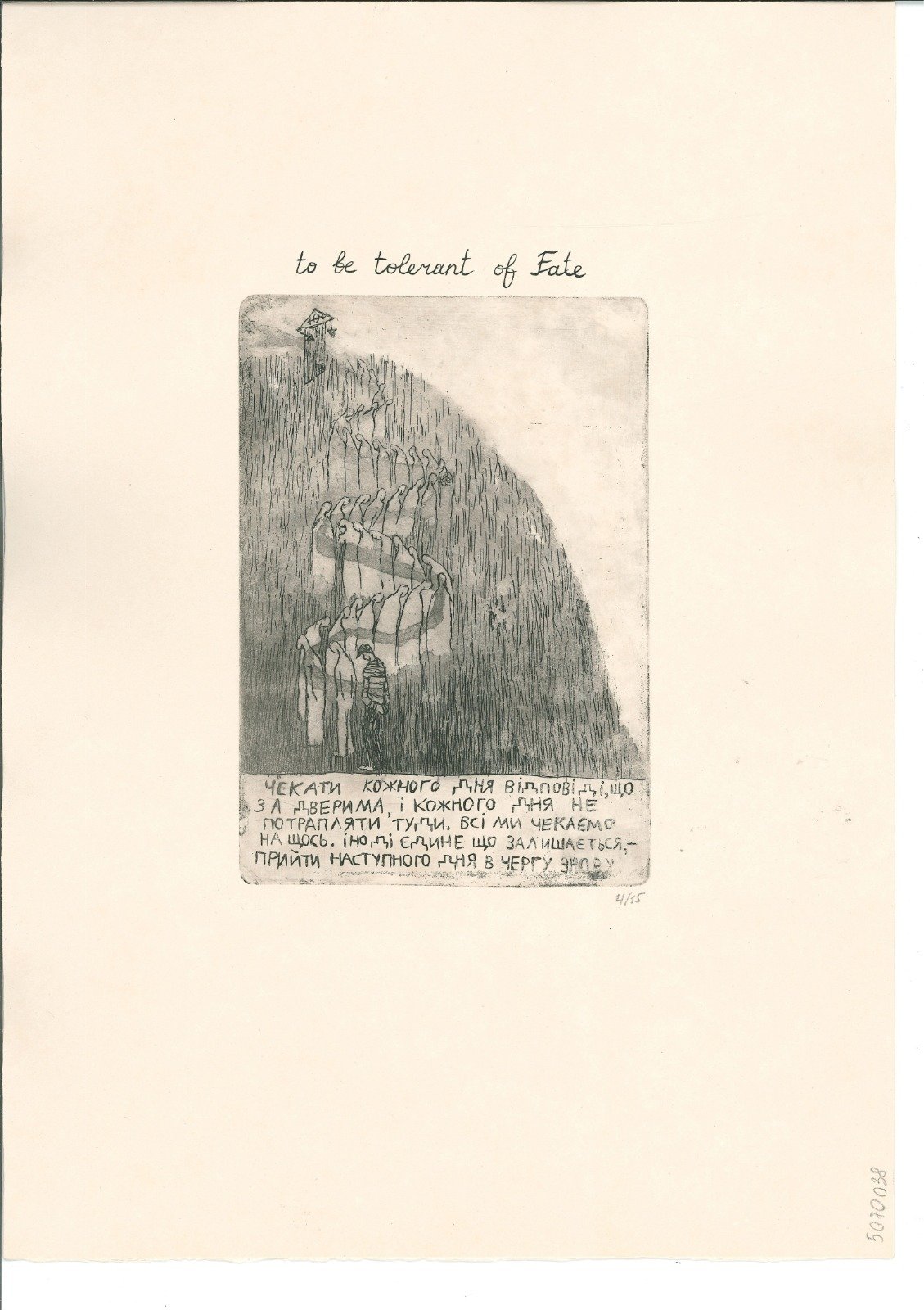

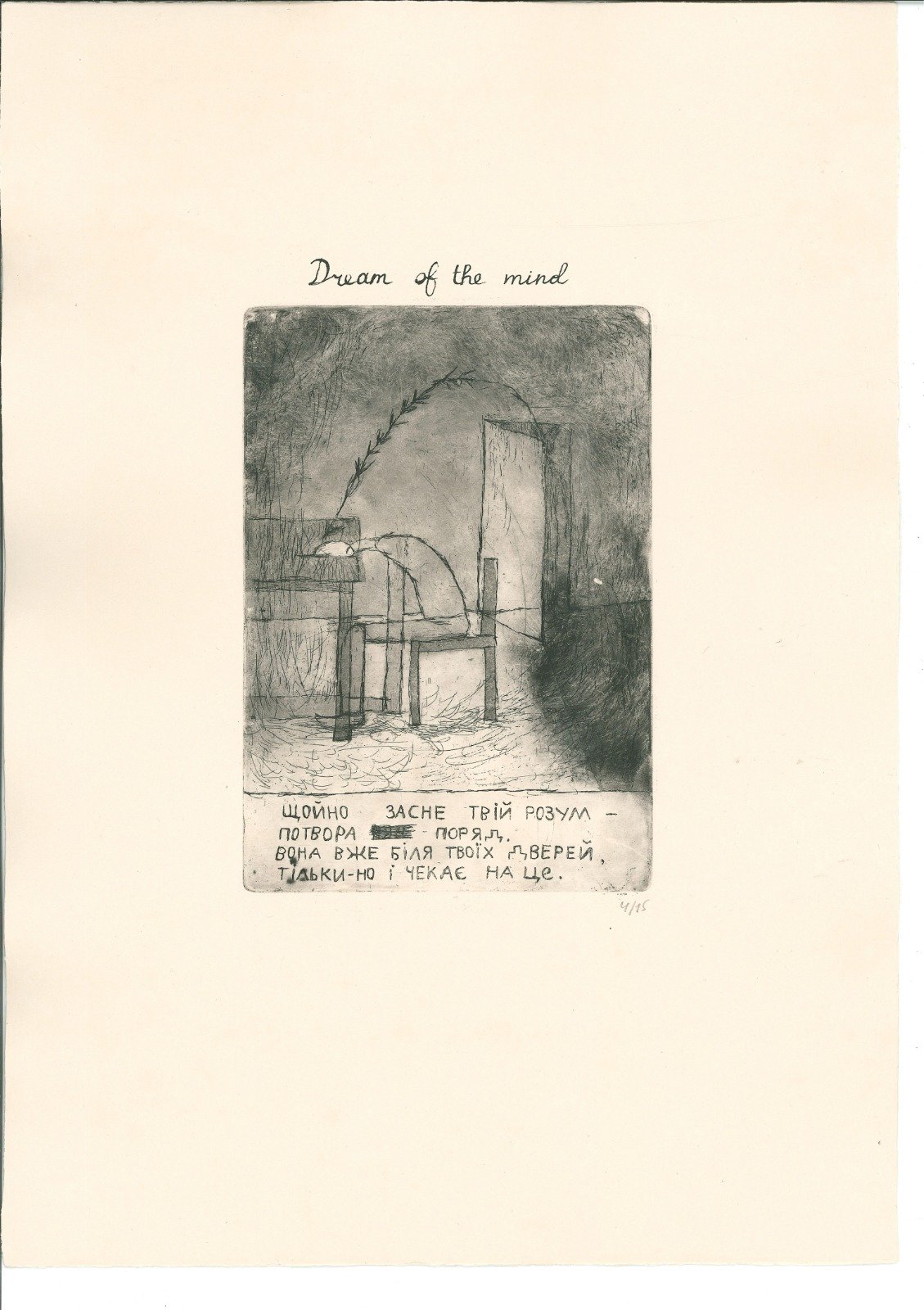

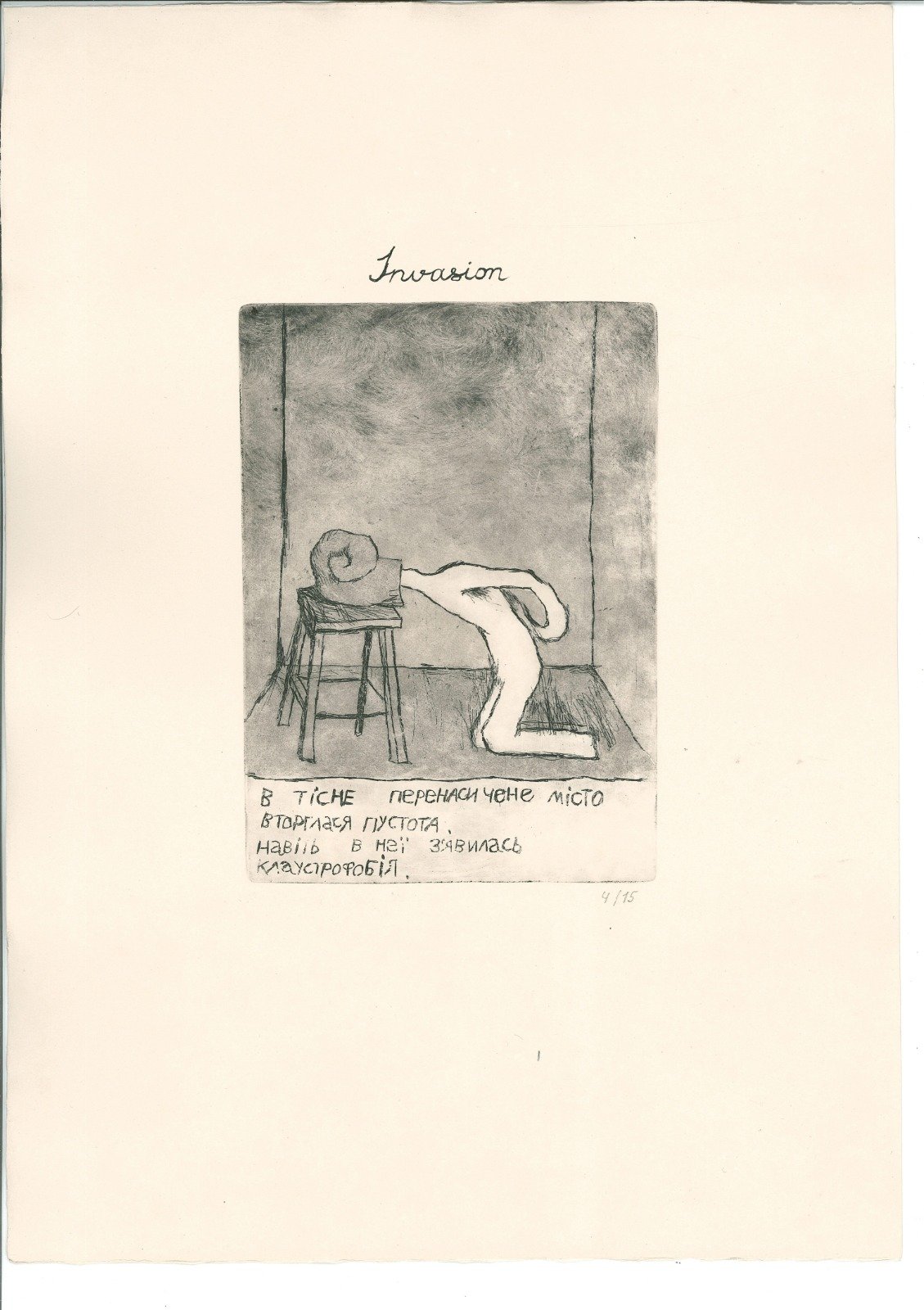

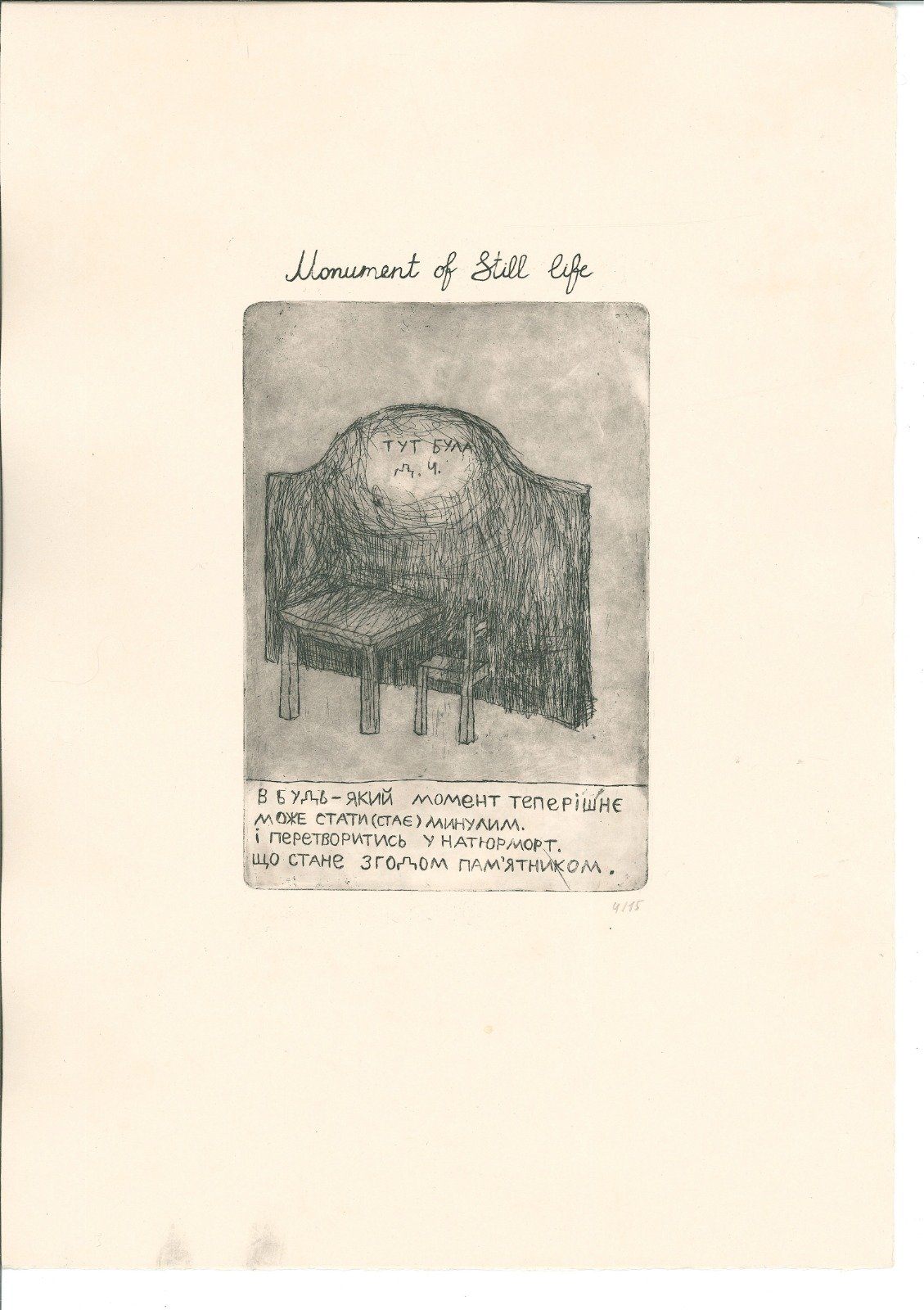

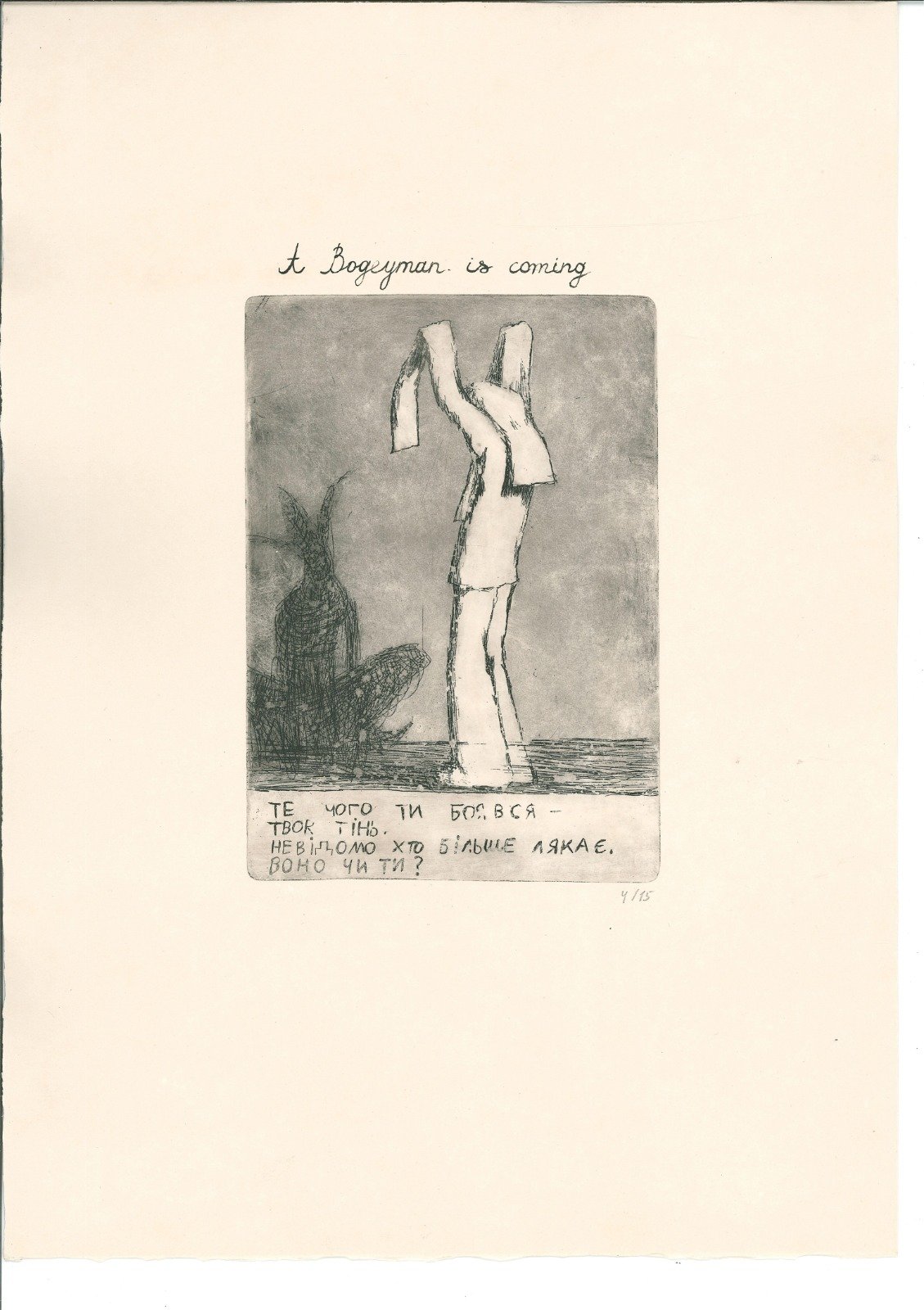

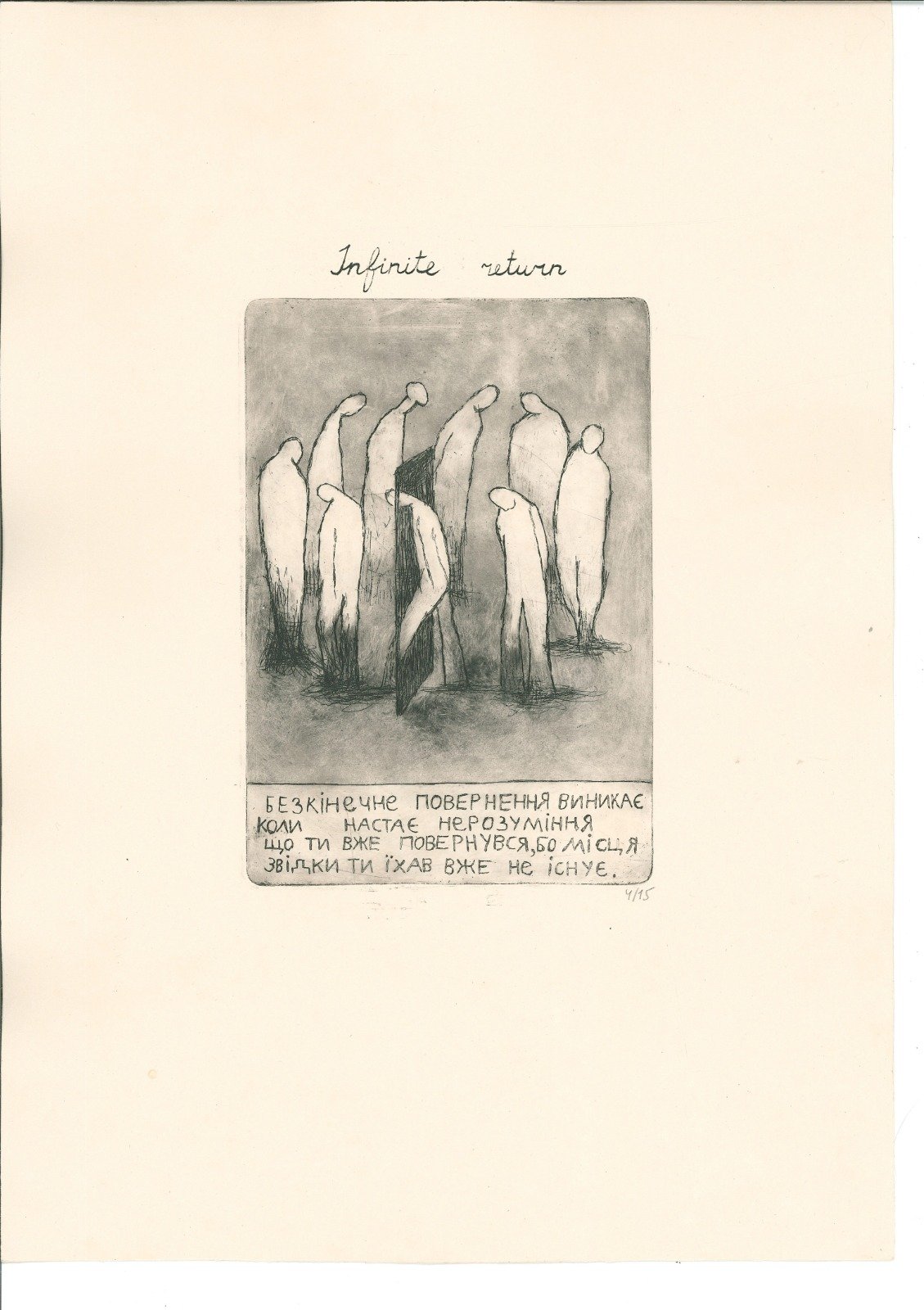

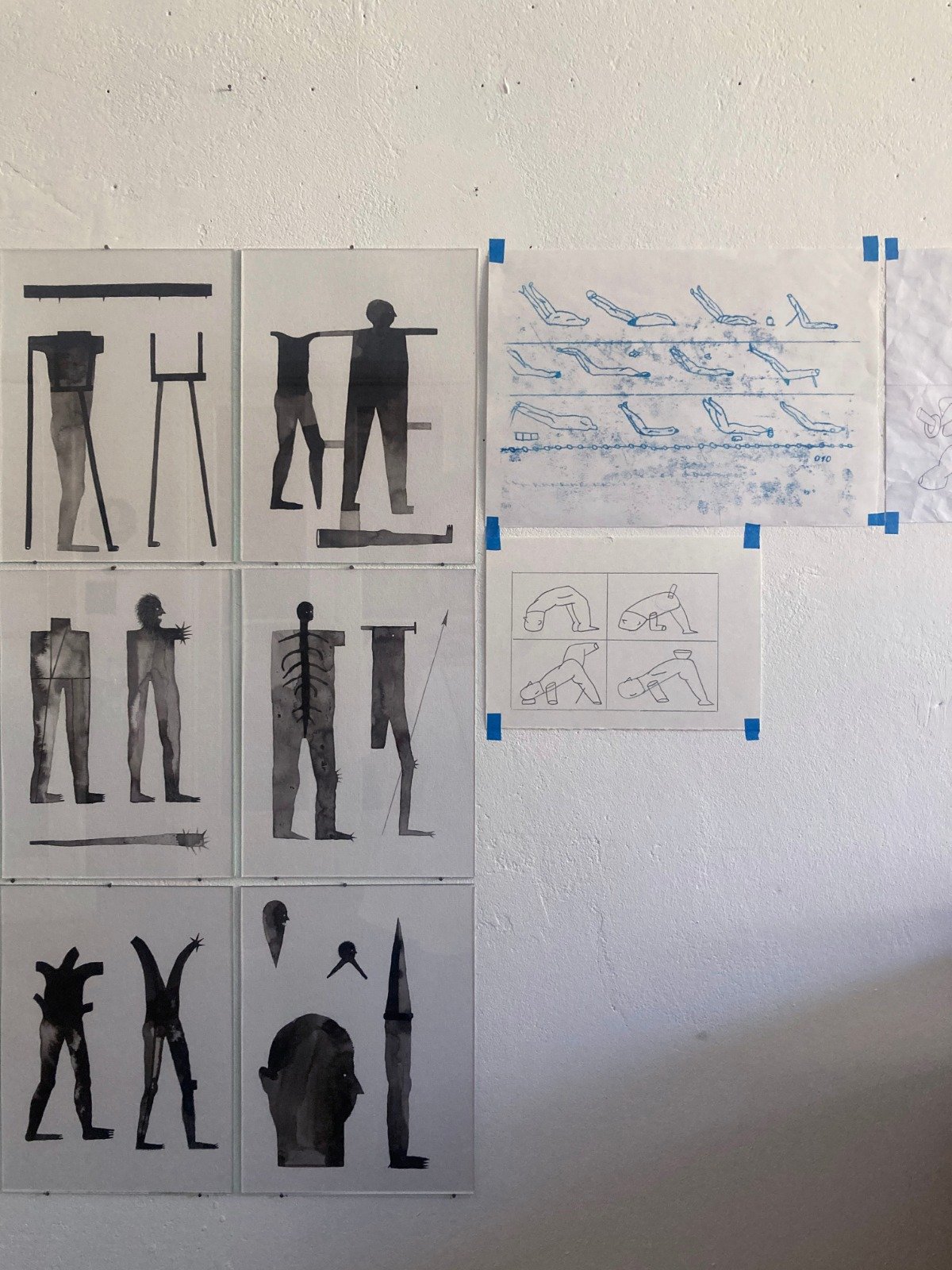

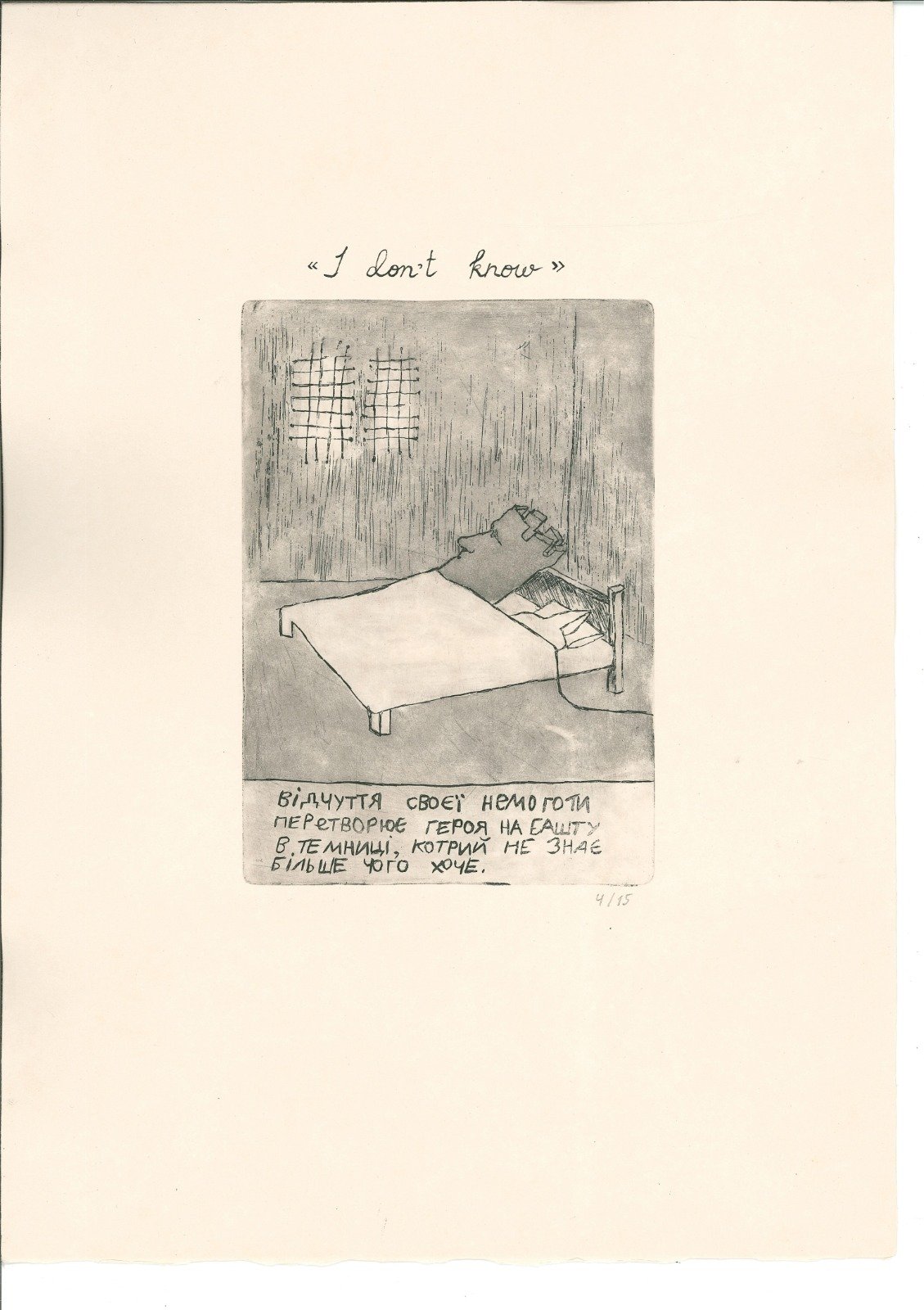

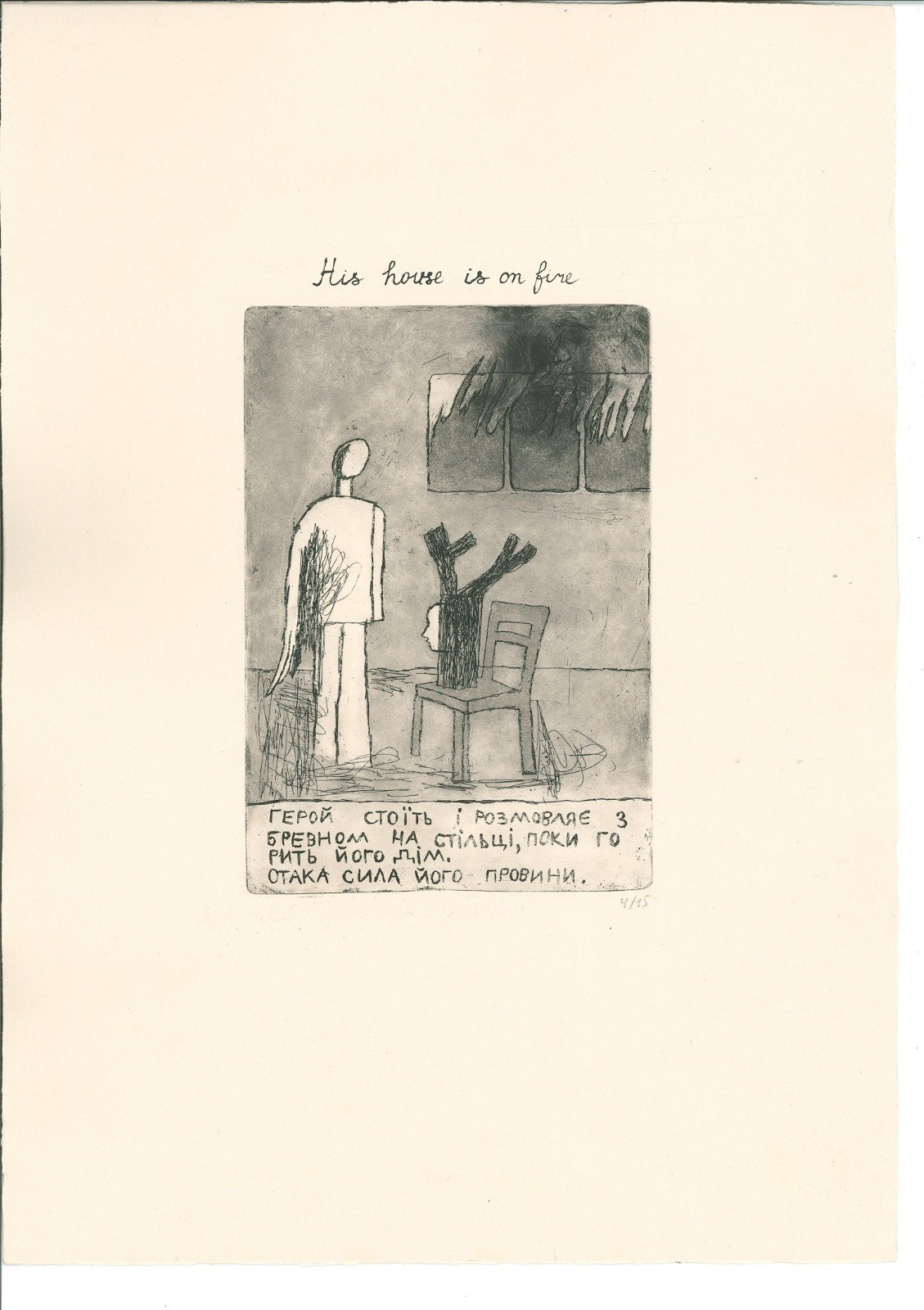

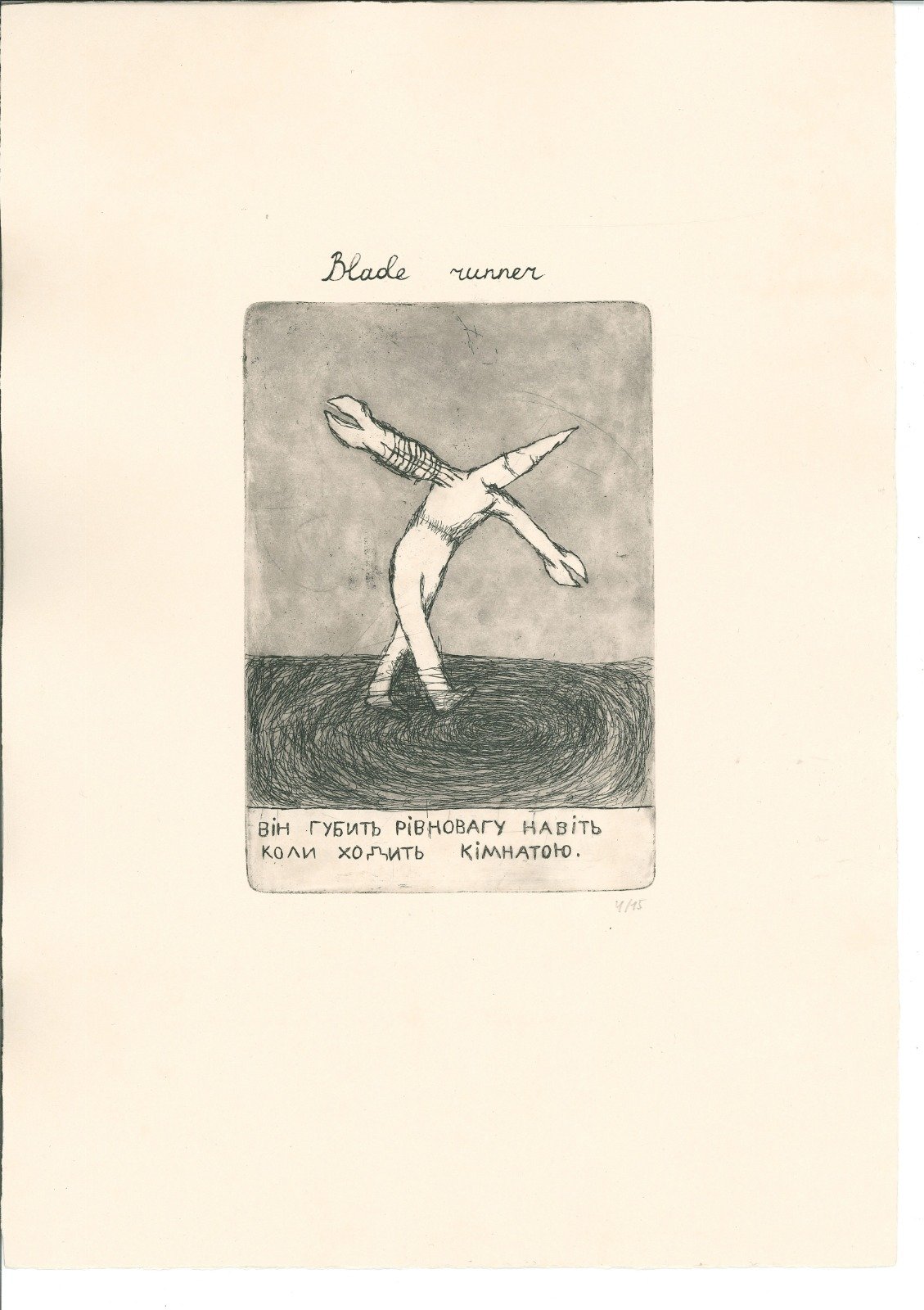

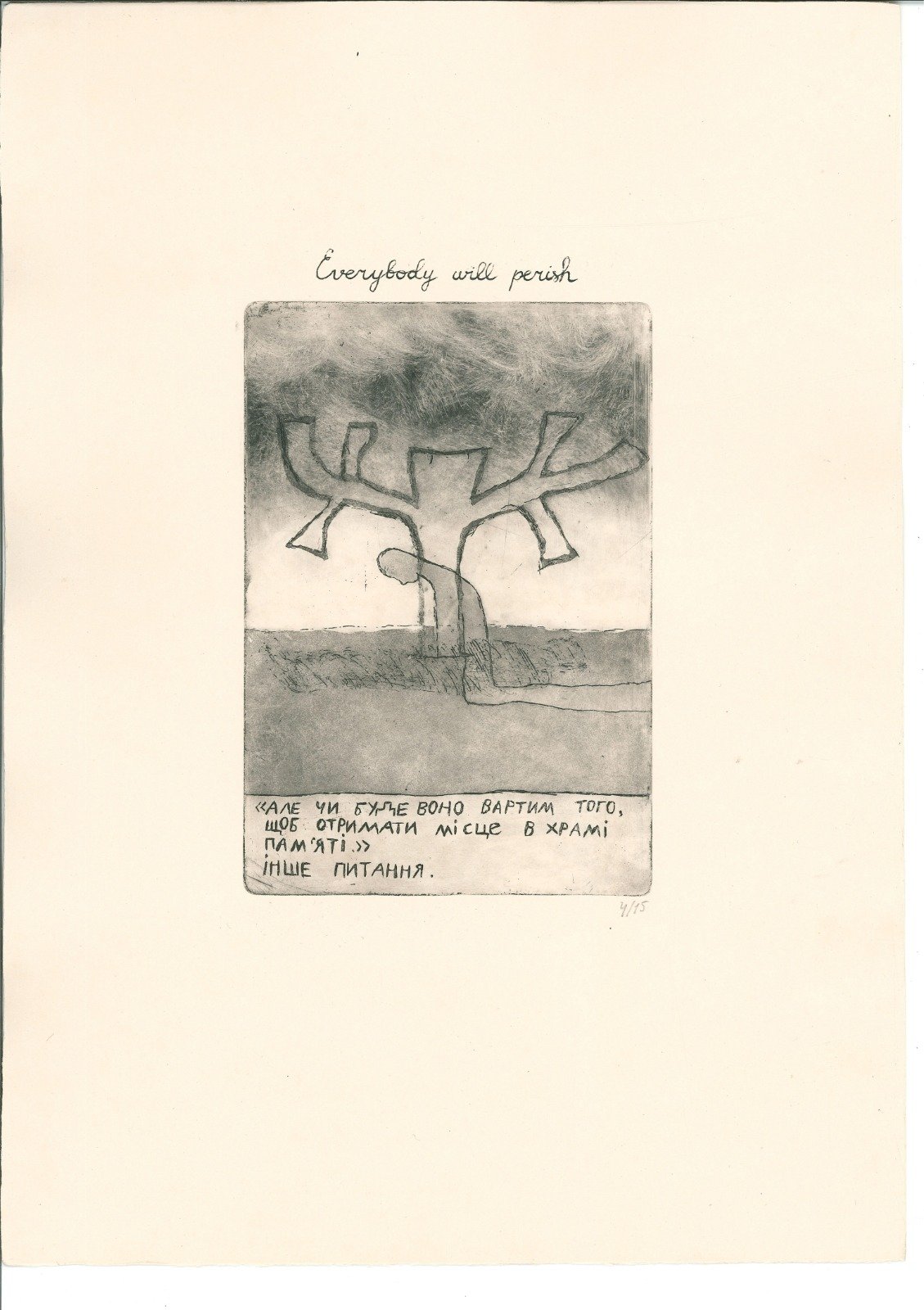

So, when Vogel writes that sadness is the material of life, I will now add: life itself is no less a sticky material – and it is that from which art is made today. And, how do we recognize it within everything? How, for example, do we not recognize art, but life, in Goya’s Caprichos – a series of etchings of striking social satire for the time. I recalled Goya because of the influence this series had on the artist Dasha Chechushkova, and her aquatint series which she dedicated to the loss of ordinary life. All her works are monuments to ordinary existence, which now, has irreversibly changed. She created these monuments slowly, carefully working through each drawing. “In a cramped, oversaturated space, emptiness intruded. Even it developed claustrophobia,” reads one of the etchings: a person in an empty room, folded in on herself like one who is held captive, lays her head on the table. The same emptiness, filled with sadness, melancholy, and loss. Caprichos translates to whims. Could life itself become a whim again?

ІІ

In every poem there is a pause.

In Aesthetic Theory, Adorno observes that “the definition of art is at every point indicated by what art once was, but it is legitimated only by what art became with regard to what it wants to, and perhaps can, become.” There is no expectation that art can make radical changes, let alone stop a war, but there is a belief that art can engage with the void and emptiness mentioned above – fill it, or maybe just create the space for something else to be born. This is a still-debated issue and it is important that this dialogue continues. And living in Ukraine during the war, we often say that life is no longer what it once was. This banal statement rests on the banality of life itself, its rhythm, and what becomes the everyday in wartime – a life that, despite everything, tries to adhere to “normalcy,” yet is decidedly anything but “normal.”

So should art remain what it once was, too? With its former definitions, tasks, challenges, and aesthetics? With its exhibitions in galleries and museums? Perhaps this is a rhetorical question, but to my mind, art has long ceased to be what it once was – at least, not what it was once expected to be: that which we believed might not stop war, but could maybe help to prevent it?

War constrains the process of creation; it sharpens feelings and perspectives. And I deliberately use the plural, for despite its totality, war – in my view – is not devoid of multiplicity: it generates multiple experiences of its own living-through. War also creates an aesthetic challenge. Nothing can equal its overwhelming visuality and transgressive power. War captures. And certain art attempts to work with this capture. But it is not about opposing war – it is about something else: a dialogue between art and war, in which artists do not resist war, for they understand that the only form of such resistance lies on the front, in combat. Rather, it is a conversation about what this war means for culture, how culture interacts with it.

Thus, when I think of our time and place I do not think of these categories as limitations, but as interlocutors. The conversations I have with artists often touch upon the origins of modernism: what it arose from and what has become of it. After all, my own understanding of art is shaped by observation, coexistence, and displacement. War translates everything into an intensely physical dimension: beneath displacement lies migration and loss of place; beneath coexistence – the literal understanding of the difference between life and death that arrives during shelling. On this profoundly material and linguistic level, art, I believe, moves into an opposite plane – one formed by a different kind of sensitivity, processuality, and openness to circumstance. “Rawness,” “accidentality,” “errancy,” “unfinishedness,” it is a shifting state – this, to my mind, is what shapes today’s art in the present tense, and opens the space for something new.

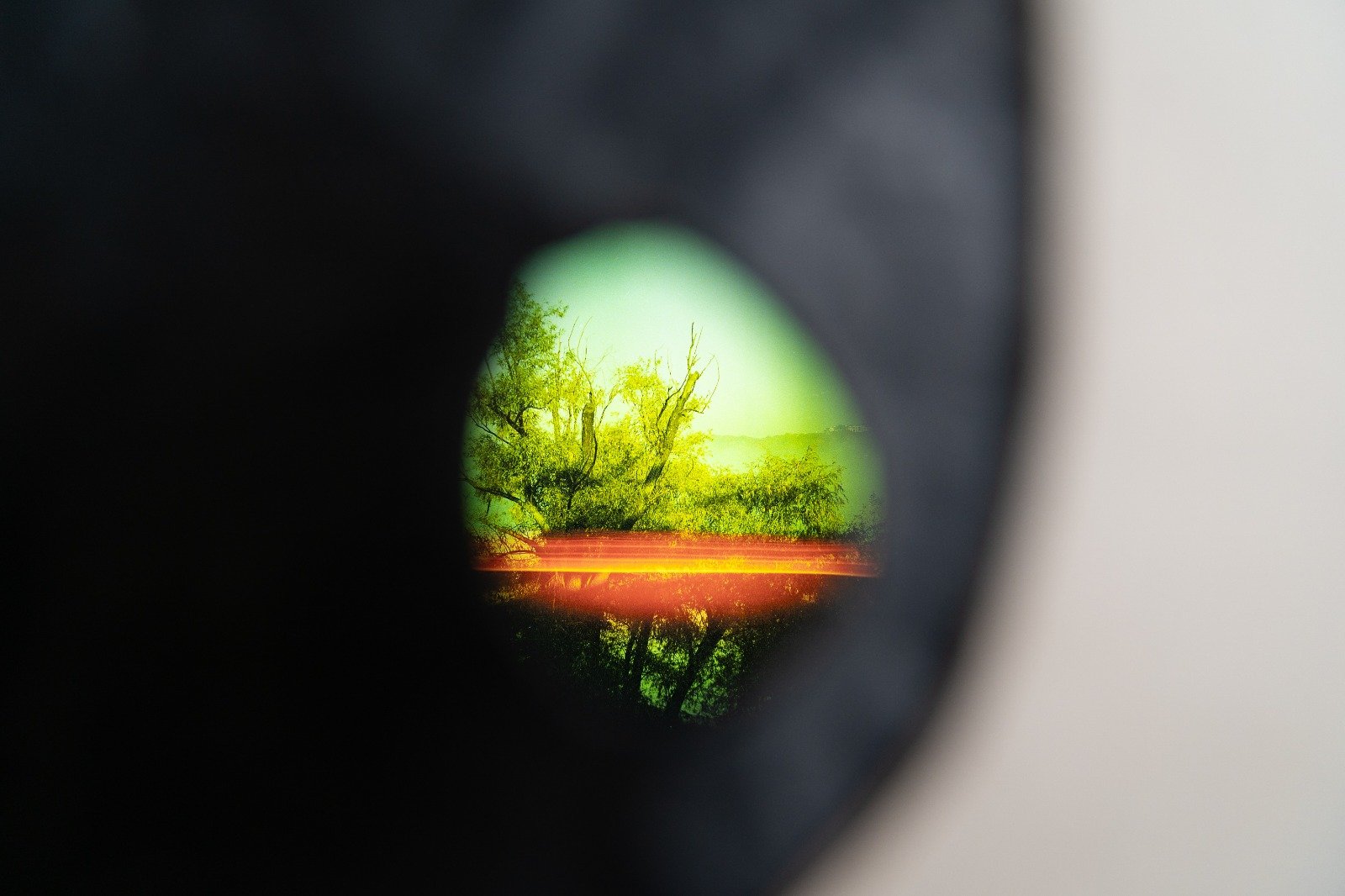

Let me describe it with an example – Oleg Sentsov’s film Real. During the summer 2023 counteroffensive, Sentsov – serving in an assault brigade – finds himself with his unit in a trench after their BMP is hit. By chance, a GoPro camera is switched on. What it records is ninety minutes of war’s raw contingency: chaos that cannot be grasped, let alone controlled. There is no editing, no aesthetic intervention. And yet Real conveys with brutal precision what the front feels like. The film consists of a single, uninterrupted, accidental shot. Sentsov remains offscreen; instead, the viewer inhabits his body – his voice, his movements, the turns of his head, his gaze. The body on screen becomes the viewer’s body. The film is structured by the suspense of waiting, the shared anticipation of rescue. It begins and ends accidentally. But for me, the true ending arrives with the credits, where we learn who appeared – either in image or by voice – and who survived after the battle itself, which remains absent from the film. A second ending occurs outside of the film when those same soldiers appear at screenings of the film. This encounter recalibrates perception: life is real, death is real, art is real. Real is also the name that was given to this battle, to this point on the map, by the Ukrainian soldiers, in the name of their favorite Spanish football club.

While Sentsov insists he did not make a film, I believe that this very negation – this accidental form within an accidental context – has transformed that which we once called art into something more powerful. And to this point, Real is not an isolated example. Bohdan Bunchak’s installation Everything That Obstructs Becoming a Prayer, Becomes One emerges from a similar condition – created in 2023 after the artist, who had volunteered to join the front – was seriously wounded and subsequently underwent rehabilitation. This collage was created from his memories and thoughts. Or one another example – Katya Buchatska’s exhibition Given: 1. Your Safespace Is On Fire, 2. Trimester, 4. Granny (2025) unfolds precisely within such conditions: prolonged war, pregnancy, caregiving, a solo show, Duchamp. “If life were a school math problem,” curator Natasha Chichasova asks, “what would count as the given?”

Thinking of these artworks, I follow Debora Vogel, who used montage as a format that corresponds well to the cruelty of life and its simultaneity, chaos, and emotional pressure. For Vogel, collage arises from facts, yet facts are never excluded from the context – Vogel herself was born in 1902 and died in 1942 in a Ghetto in Lviv. She believed that selection and juxtaposition of facts already constitute interpretation. Vogel turned to collage for its movement and rhythm, categories essential to conveying a tense historical present. But what are movement and rhythm today? Not merely cinematic motion or shifting images, but the internal movement of a work: the movement of thought, of a practice. Wartime produces a different rhythm of life – sirens, blackouts, moments of enforced silence, news from the front interwoven with exhibitions, friendships, care, and exhaustion. The pause is no longer chosen – it is imposed.

For Adorno, the pause is the site where contradictions collide; it is not absence but structure – an echo of social silencing. The pause can be understood as the space where heterogeneous elements meet and adhere, where art directly encounters war. It may appear as silence – a black screen, a shift from image to text – or as a withdrawal from artistic practice under the pressure of combat or loss. Ukrainian historiography often names such moments “ruptures”. But what matters is repetition: why these pauses recur, how long they last, and what occupies the spaces they open. Rupture does not sever; it binds. In this sense, rupture also functions as collage: not as a separation, but an adhesion; not destruction, but the exposing and binding of heterogeneous fragments under conditions of strain.

Odesa-born artist Yuri Leiderman used the metaphor of rupture not to name catastrophe but to describe an inner space within complex processes: a space of freedom, contingency, refusal. In Moabit Chronicles, rupture becomes a tactic of survival – a way to escape the continuity of Soviet discourse, a flight from history’s demand to subordinate art. For Leiderman, rupture resists singular interpretation and the authority of the whole. It illuminates fragmentary experience – individual and collective – outside any center.

The trope of rupture is important precisely because it does not imply primacy or uniqueness: rupture is a form of collaged adhesion. Collage allows a form to be simultaneously complete and incomplete; to repeat without the nausea of repetition, to pause while knowing that continuation is inevitable, even if its temporality remains undefined and its form unbounded. Rupture, understood as collage, does not operate metaphorically. On the contrary, it speaks in what Debora Vogel called “the language of concretes.” Only through the grouping of concrete things does a metaphor of reality emerge.

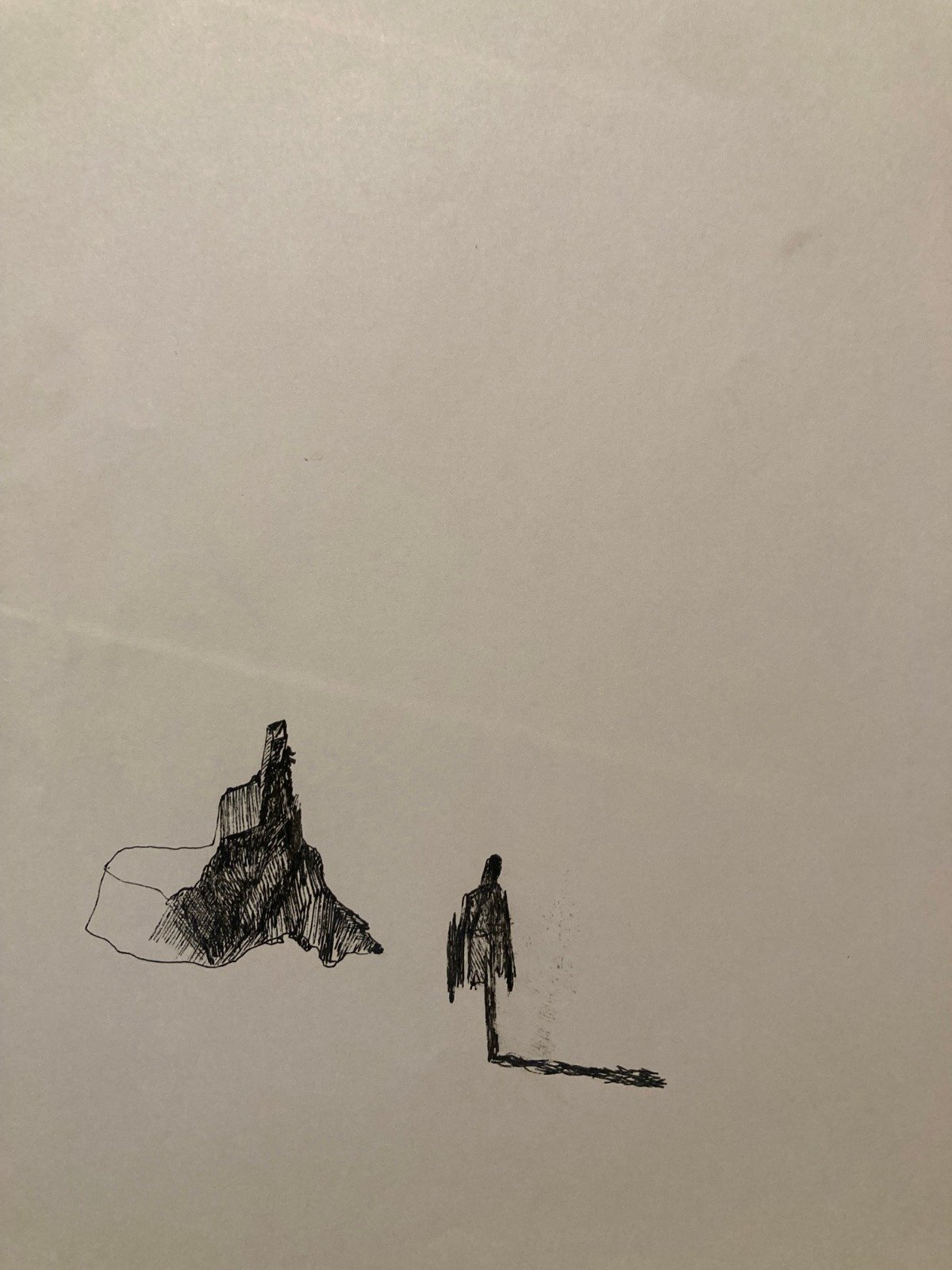

This evidence of such a reality manifested itself in another work by Stanislav Turina, A Few Kilograms of Exhibitions; a project composed of six autonomous exhibitions, each bearing its own title. One exhibition, Stones and Remnants of Light Industry (Threads), consisted of stones ranging from pebbles to heavy slabs, spread across the gallery floor, with remnants of thread laid atop them. The threads were leftovers from Turina’s sewing practice, which for him is both everyday labor and artistic method.

These stones and threads have nothing to do with war. They are witnesses of life – or, more precisely, evidence of its residue. Yet war paradoxically renders even remnants valuable, as that which survives. In the gallery, these materials speak not of violence but of routine, tactility, and material presence; of the tension between roughness and delicacy, stone and thread – like the tension between life and death itself.

Could this work exist outside the context of war? When thinking about wartime art, one might expect overt imagery. Yet the force of this work lies precisely in its restraint: its visuality emerges through being with the work, through contemplation and coexistence. The viewer’s body enters into a shared scale with these small bodies of stone and thread. Scale matters. Through its scale, we grasp the consequence of tragedy. The work returns us to an awareness of space and time – to the events that have unsettled the rhythm of being.

A different articulation of rupture appears in Yaroslav Futymskyi’s performance A Few Weak Signals That Do Not Testify to the Real, which was performed in Kyiv on July 31, 2025, the day after one of the city’s most massive bombardments. The artist doubted whether the performance should take place at all – whether there was space for the art to speak amid such devastation. This doubt became the work’s condition. The performance unfolded as a collage of spoken doubts, poetry, and interactions with objects: notebooks, vegetables, a microphone, a loudspeaker, and a round glass object that absorbed sound, partially or at times completely, devouring speech. The artist spoke into this object, rendering their words inaudible. What remained audible were two repeated phrases: “A few weak signals that do not testify to the real,” and “I speak to the zemlya (earth).”

In Ukrainian, zemlya means the ground beneath one’s feet, the soil thrown onto graves, and the planet itself. A six-letter word that holds both the intensely local and the boundless. Thus, researcher Darya Tsymbalyuk notes that the word zemlya has no equivalent in other languages. Here, ground is both soil and the ground of history – concealing prior narratives and literally covering the dead. Zemlya is not an object but a subject. If one speaks to it, it answers. Zemlya becomes that interlocutor when no one else is left nearby.

A few weak signals multiply and suggest incapacity and warning, naming the brutality of war. To not testify to the real is to remain outside existing artistic tools and forms.

ІІІ

“What arises from the air, and what dissolves within it?” – asks, or perhaps asserts – the artist and now soldier, Pavlo Khailo, in his essay from 2020.

Combat encounters, injuries, rehabilitation, the experience of shelling and survival – these works, in fact, depict life almost immediately after confronting death; not after the war, but in that moment of critical proximity that remains inaccessible to the wider public. This temporal state could be described as the immediate past or the threshold of the present – the latter, to my mind, most aptly captures the problem of presence, gaze, and attention. Moreover, the kinship between the threshold of the present and the threshold of pain underscores the strained temporality of wartime existence and its constant, volatile shifts.

“In the conditions of war, these changes are perceived more acutely, and it feels as though you cannot physically keep up with them. Yet, following the deadly logic of probability that governs life during war, it becomes clear that one day everything around may turn into zero,” says curator Natasha Chichasova about Katya Buchatska’s exhibition Given: 1. Your Safespace Is On Fire, 2. Trimester, 4. Granny. This exhibition refers to Marcel Duchamp practice but emphasizes, above all, the crucial importance of time in a new “deranged world, war, pregnancy, daily rituals, and artistic practice.”

Art history traditionally describes two primary relations: between artist and artwork, and between artwork and viewer.

Adorno insisted that the artistic subject is always social rather than private. Yet these works share another defining quality: privacy. Sentsov’s Real, for example, records an experience bound to a specific moment of military service. The viewer was not meant to be present – not meant to hear these voices or see through this lens at all. Something that could be called a secret – hidden, intimate – is suddenly exposed, shared, distributed. The burden of this secrecy is no longer carried by one alone. Privacy is inseparable from time and space, from the concrete conditions under which these works came into being. And it is this private dimension that ultimately reshapes our way of looking at art. And so the question posed by the title – “what obstructs art” today is not an external force, but its very medium, and has a simple, concrete answer: war. We only have to understand the meaning of this word, understand what it is filled with and what it consists of. So I will leave you with a linguistic pause, one to be read and answer as long as the war continues:

If this — is war. Then life — is…

If this — is art. Then art — is…

IV

This text was originally written in Ukrainian in 2025. It appears in English only now, in January 2026, at a time when power outages in Kyiv last up to twenty hours a day. In these pages I write about ideal days; yet in the days unfolding now. In 2022, one Ukrainian media published essays by colleagues from the Balkans, urging Ukrainians to prepare for winters: the first would be difficult, the second no easier, and then the third, and the fourth. No one knows how many such winters there will be. And yet, in cold, domestic conditions, the days still arrive – perhaps not ideal ones, at least not now, but they do arrive.

I wake up and make coffee. Then another. Each morning I promise myself to begin the day with a glass of water, and each morning I fail to keep that promise. Sitting on the windowsill, which looks out onto the inner courtyard of a modernist building, I check messages from friends. Everyone is safe. There is no shelling, there is no war. Not in Ukraine, not elsewhere. Mornings have grown warm and filled with light. I hear a bird singing outside. Let me check what kind of bird this is.

But today it is mid-January; the month has barely passed its halfway point, as has the winter. How many such winters do we have left? The mathematics of war produces difficult equations – or rather, it does not balance things; it marginalizes and forms inequality. I no longer know which days are ideal, and from time to time, while searching for things in my home in the dark, I come upon doubt, fatigue, and apathy. Then I return to what surrounds me and think of those birds singing in the midst of a harsh winter; I look at the architecture around me, which has seen more than one winter. They say that one cannot see in the dark, yet some things are, in fact, much more visible.

Kateryna Iakovlenko is a Ukrainian writer and curator who currently serves as Cultural Editor-in-Chief of UPB Suspilne Media. Having a background in journalism and research, she transforms visual, archival, and documentary materials into exhibitions, nonfiction essays, and librettos that examine the impact of war on aesthetics, art, and memory.