Jan Zálešák`

The Trafó Gallery in Budapest is part of the cultural center of the same name. As a municipally funded institution, Trafó, together with the Budapest Gallery, remains one of the few publicly supported art spaces in Hungary’s capital that has managed to retain a measure of autonomy from the direct influence of Fidesz’s cultural politics. Over the years, Trafó has established itself as a site dedicated to contemporary art, alternating between solo exhibitions of Hungarian and international artists and curatorial projects in the form of thematic group shows. Despite the relative precarity that shadows its operations, curator Borbála Szalai and her colleague Judit Szalipszki have consistently maintained a program of remarkable quality have consistently maintained a program of remarkable quality, recently featuring shows of prominent artists, such as Hito Steyerl and Wolfgang Tillmans. It is within this curatorial framework – defined by Trafó’s ongoing effort to sustain a vivid dialogue between the local scene and the global contemporary art – that the current exhibition by French artist Cyprien Gaillard (b. 1980) takes place.

Gaillard first came to attention in the mid-2000s and by the end of the decade, had become one of the most visible representatives of a generation shaped by the waning years of the Cold War, before the rise and full saturation of the internet. When Hal Foster published his now-canonical essay Archival Impulse in 2004 – identifying a tendency among contemporary artists to work with archives and memory through the conscious embrace of the fragmentary nature of research of material history – Gaillard was only beginning to articulate his artistic language. Yet within a few years, his practice could easily be aligned with this same current, one that came to be theorized under a variety of labels. Among the attempts to conceptually grasp this phenomenon was the notion of “modernology.” The term, originally coined by Japanese architect and anthropologist Kon Wajiro, was later adopted by Austrian artist Florian Pumhösl as the title of one of his works, and subsequently used – this time in the plural – by curator Sabine Breitwieser for her large-scale exhibition Modernologies at MACBA in Barcelona.

Reflecting on that exhibition, Czech art theorist Karel Císař observed that it “explicitly thematized the efforts of artists of the younger and middle generation to seek a new evaluation and actualization of the project of modernity as a possible site of resistance against the growing influence of neo-conservative tendencies in economics, politics, and culture. The inquiries of these artists do not take the form of a nostalgic return to a world-condition that has never actually existed but rather represent modernity as a completely actual project.”[1]

This position resonates with the thinking of Dieter Roelstraete, who around the same time described a similar phenomenon as the “historiographic turn” in contemporary art.[2] Roelstraete identified the rise of neoconservative forces in the years following 9/11 and the onset of the “war on terror” as a key catalyst for the intensified artistic interest in “past futures.” His essays offered an alternative to Foster’s “archival impulse,” proposing instead the idea of an “archaeological imagination.”[3]

The artistic potential of literally uncovering the layers of earth beneath which remnants of the past are buried – material that can be reactivated to stir new semantic or affective resonances in the present – was demonstrated by Gaillard in his 2009 project Dunepark, realized on the Dutch coast. There, the artist excavated a Wolrd War II bunker long buried under the sand. This site-specific intervention, though reminiscent of certain iconic works of Land Art, was less concerned with updating the phenomenological experience of landscape than with exposing an unhealed wound in the collective memory of a nation that, like so many others, preferred to see itself primarily as a victim of World War II.

This project, rare within Gaillard’s oeuvre for being realized as a work of public art, already contained many of the motifs that would come to define his practice. Firstly, an interest in the ruins of modernity, presented against the seemingly neutral backdrop of nature. Into this backdrop enters another temporality, distinct from the human scale of history. It is not yet what we might call “deep time,” but rather a natural time, resistant to the teleologies that propel human action forward; stretching, contracting, and puncturing time as they go.

If we move from this contextual framing of Gaillard’s practice toward the Trafó exhibition, we can notice that a temporal dimension is already inscribed in its title. Ocean II Ocean is not merely about the meeting or collision of different places – it is also about the infinite depth of time embodied by the oceans that cover most of the earth’s surface. The “forgotten space” (Allan Sekula) of the sea has always functioned as a frontier where, since the early sixteenth century, the histories of modernity have been written: histories bound to colonial expansion, to the transformation of nature into capital within necropolitical regimes of extraction. The ocean, like outer space, is both infinite and ungraspable – distant for those of us living inland, yet omnipresent: in the fossilized remains of marine organisms beneath our feet, and in the commodities that reach us via transoceanic routes from remote parts of the world.

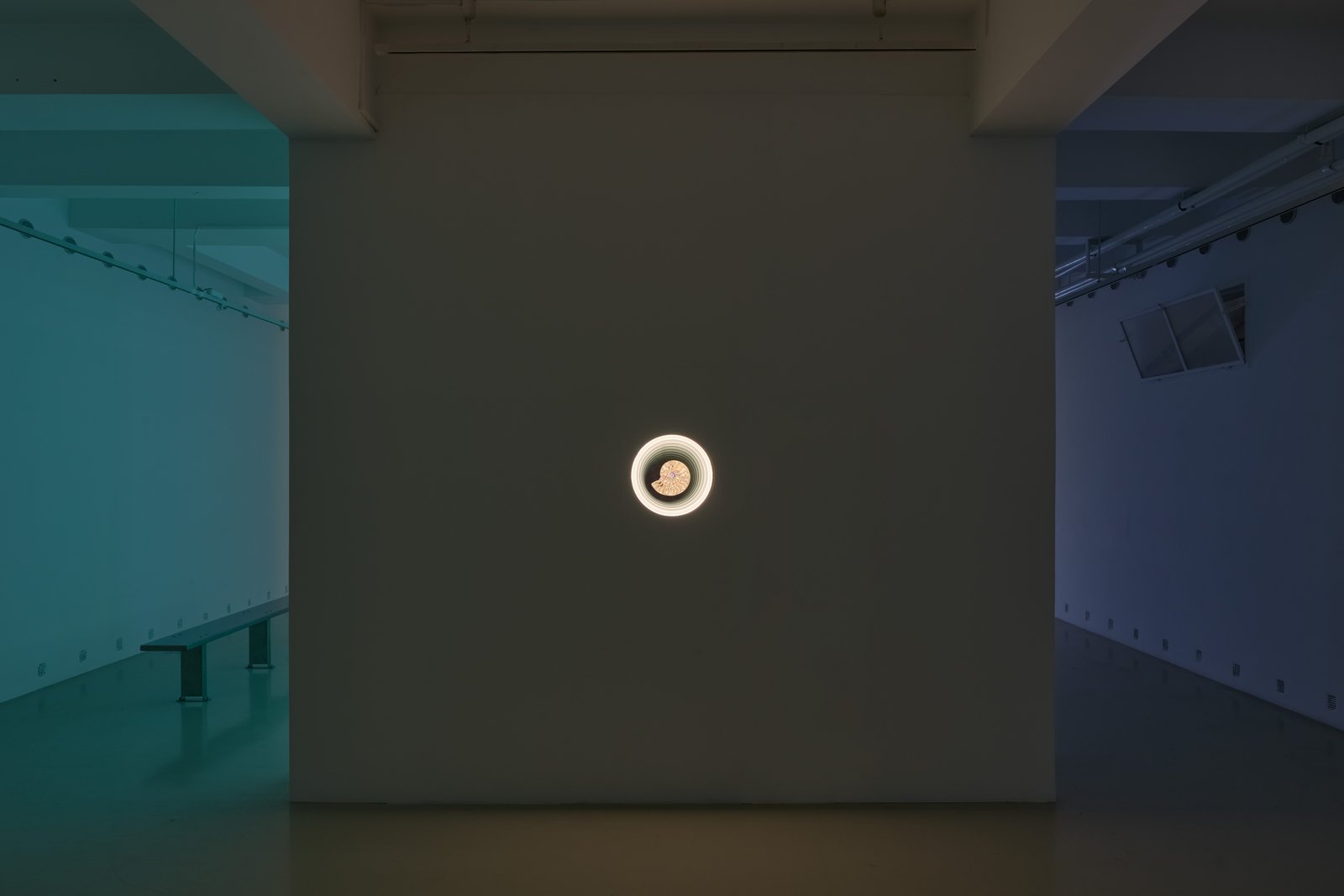

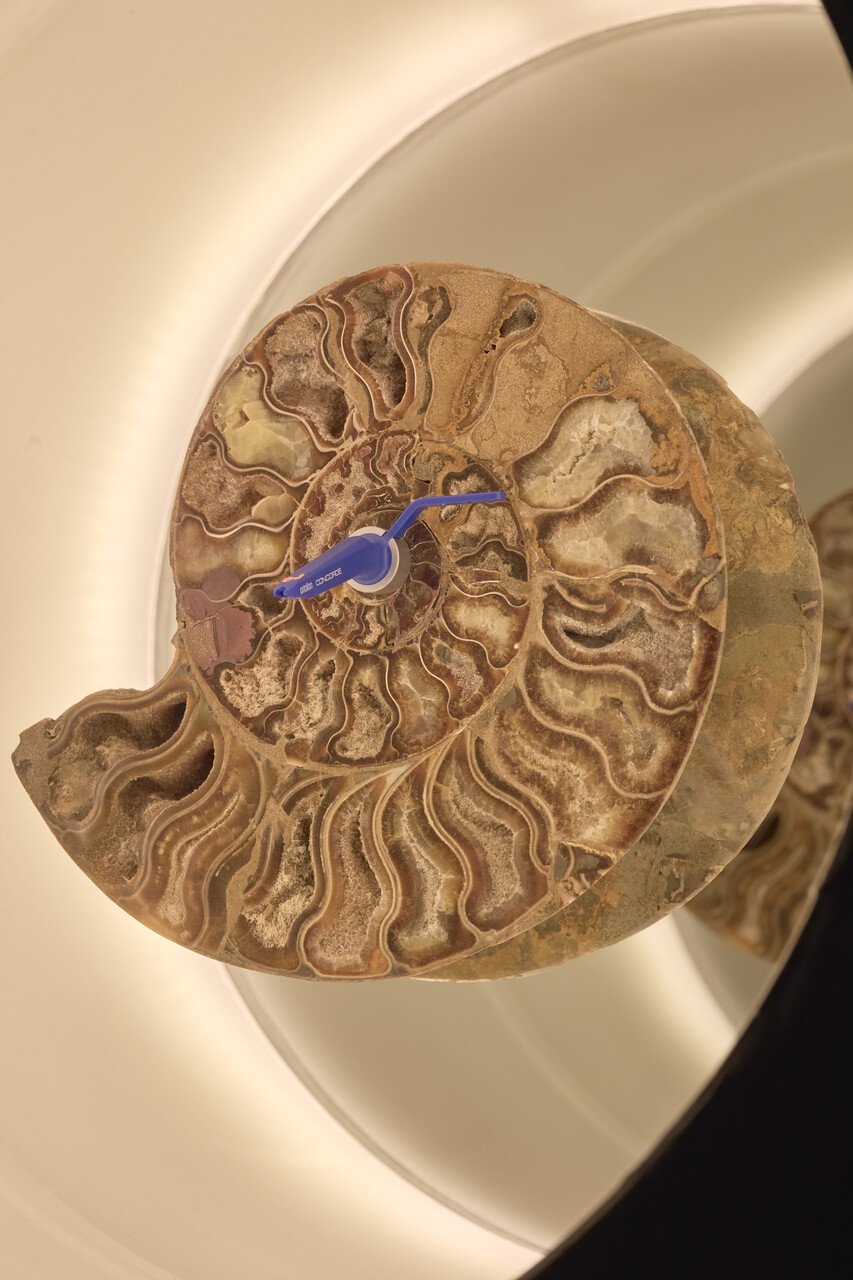

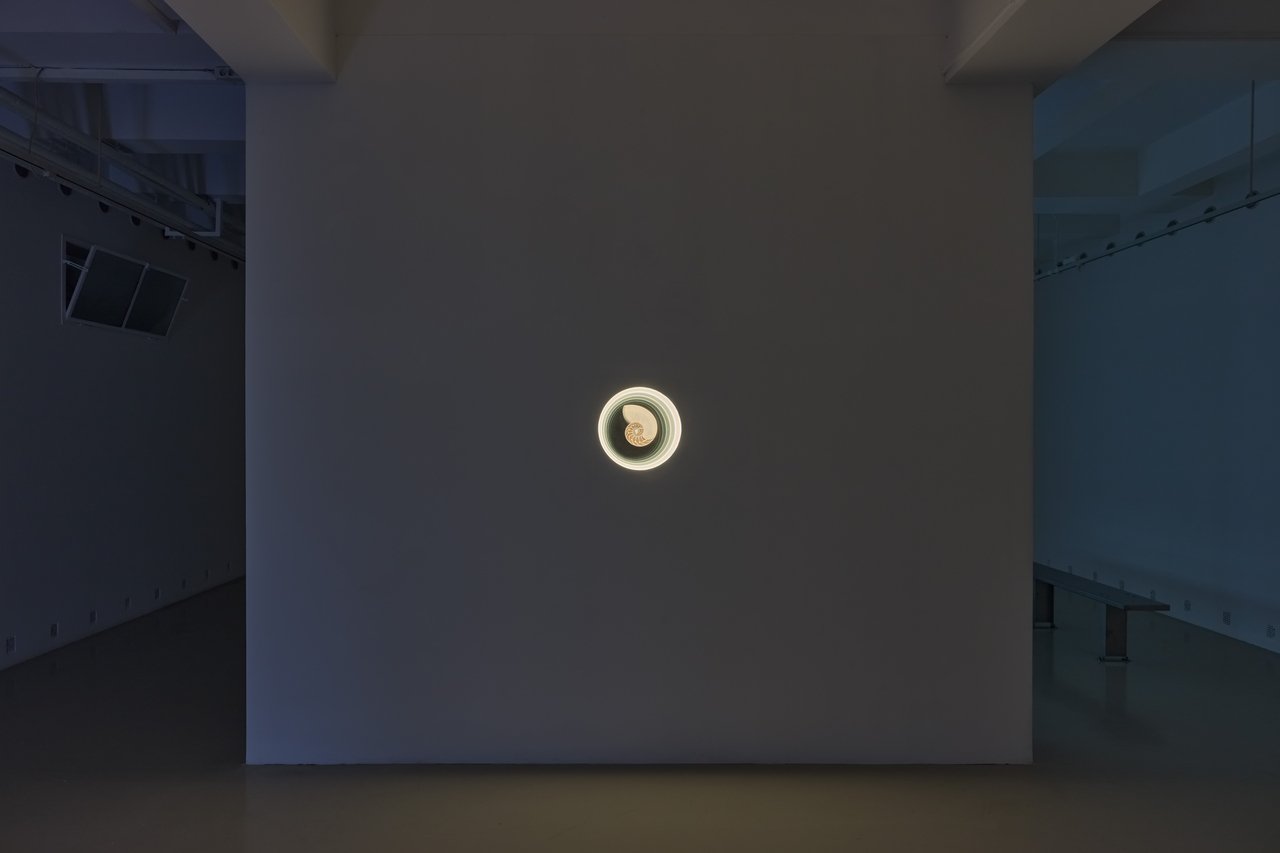

The architecture of the exhibition Ocean II Ocean mirrors the spiral motif found in the fossilized shells of ammonites. Ammonite Dub (2009) is the first object to catch the viewer’s eye upon entering the gallery. Installed in a softly illuminated niche within a plasterboard wall, the cleanly halved shell of the prehistoric creature evokes not only the deep duration of time but also the remarkable persistence of natural phenomena. The inner structure of the shell, revealed in cross-section, is a textbook example of natural geometry. The delicate spiral recalls compositional schemes once used to explain the harmonic structures of classical painting, the organization of animal and plant bodies, or the grooves of a vinyl record – an association explicitly drawn out by the work’s title.

The repetitive rhythm inherent to dub music – whose purpose is to synchronize a crowd of bodies into a single pulsating organism – connects once again to the question of time, understood not as an abstract physical quantity but as something profoundly material and embodied, both visible and invisible, embedded in the very substance that forms the universe, its celestial bodies, and the corporeal forms that inhabit them.

Two of the three videos presented at the gallery date from around 2009, the moment when the aforementioned tendencies of modernology or the historiographic turn reached their peak: The Lake Arches (2007) and Pruitt Igoe Falls (2009). The narrative of The Lake Arches, a looping video of less than two minutes, is deceptively simple. Two men, stripped to their swimsuits, survey the surface of an artificial pond that forms part of a high-modernist housing complex somewhere in France. After a brief hesitation, they dive in. They resurface almost immediately – one of them injured, having misjudged the shallowness of the water. The remainder of the video consists of close-ups of his bloodied face and the abrasions across his body.

Risk-taking and clashes with reality. The physical expansiveness of male bodies, their pursuit of thrill as an escape from boredom or existential void set against the decaying backdrop of failed modernity – these motifs recur throughout Gaillard’s video works from this period. One of the most striking among them, Desniansky Raion (2007), takes its title from a Kyiv suburb, one of three sites the artist guides us through in the piece. The cold towers of socialist housing blocks are shot from a distance and from above, as if we were surveying an archaeological site. In the next sequence, we witness the demolition of a building from the same era on the outskirts of Paris. Finally, in St. Petersburg, similar housing estates serve as the setting for a violent street clash between two groups of football hooligans. A powerful soundtrack by French musician Koudlam accompanies the monumental imagery of the battle.

In Cities of Gold and Mirrors (2009), made two years later, Gaillard moves to the Mexican historical site and popular holiday resort of Cancún. With its editing and overall formal composition, this short film is more rhythmically charged than Gaillard’s earlier video works. In less than ten minutes, we encounter a succession of scenes: American spring breakers competing in a tequila-drinking contest; a young local man dancing, his bandana-covered face and attire evoking gang iconography; the modernist interiors and exteriors of hotels, where nature alternately functions as decoration or as a reclaiming force overtaking derelict structures; and finally, the demolition of what appears to be a hotel – an edifice that has exceeded its economic lifespan.

Compared to these more complex narratives, The Lake Arches is built around a single, sustained scene. Yet within that simplicity, all the core elements of Gaillard’s practice from this period are present: the male, disruptive energy on the verge of self-destruction; the high-modernist architecture as monument and ruin; and nature as something that exceeds, resists, and contrasts the shallow temporality of modernity and its protagonists with the deep time of natural processes.

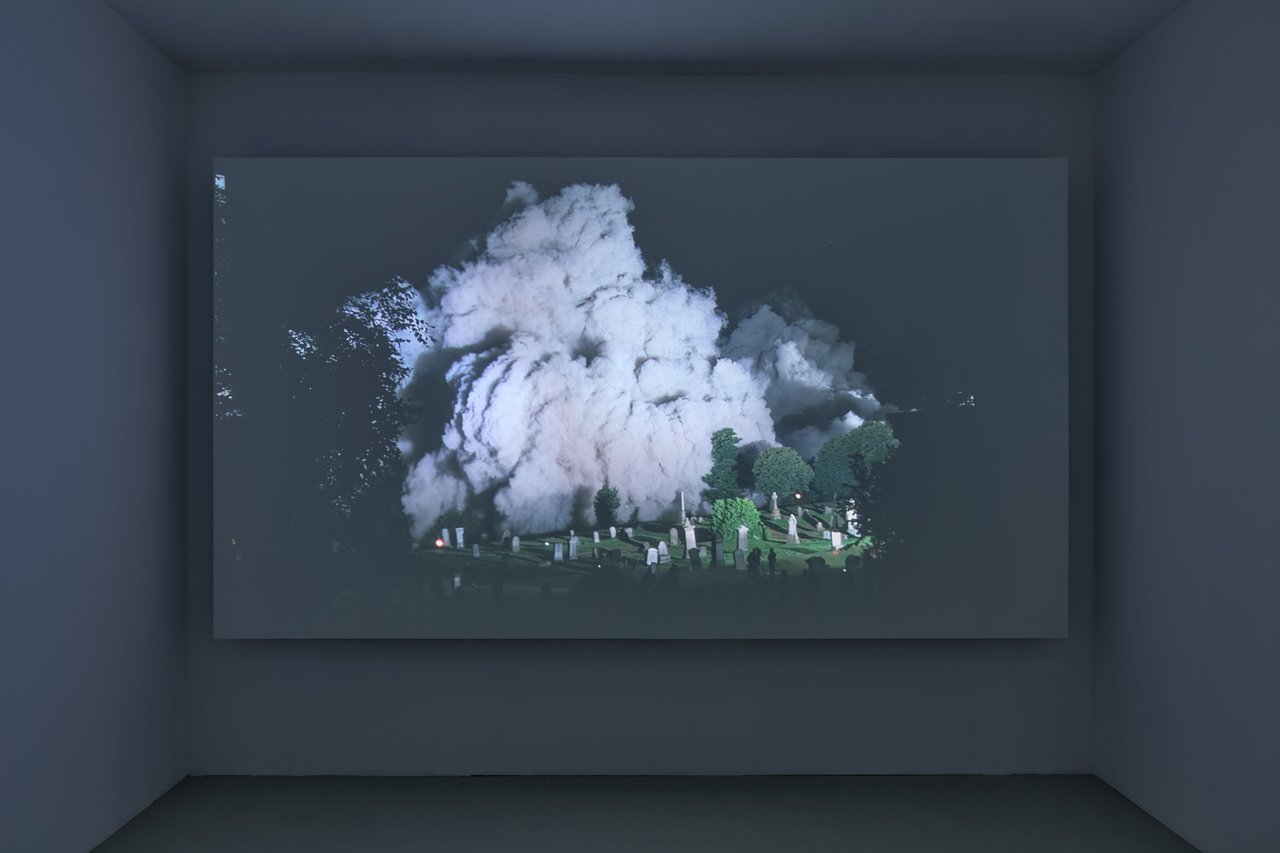

Within the exhibition’s composition, this earliest video is paired with two later works. The older of the two, Pruitt Igoe Falls (2009), combines two emblematic place-names. The first refers to the infamous Pruitt Igoe housing complex in St. Louis, completed just before the abolition of segregation and demolished two decades later after a period of steady decline. Its destruction became both a symbol of modernist urban planning’s failures and a point of departure for postmodern and neoliberal paradigms of governance. The second half of the title gestures toward Niagara Falls, fusing the two sites into a single metaphor.

The seven-minute video unfolds in two halves. In the first, we see a static shot of a worn-out high-rise housing block (actually situated in Glasgow), illuminated by floodlights, awaiting demolition. The opening minutes are nearly motionless; only the faint movements of bystanders reveal that we are indeed watching a film. Suddenly, the building shudders under the pressure of explosives, collapses in a cloud of dust, and the illuminated particles fill the entire frame. In an almost imperceptible cut, this abstract cloud – drifting downward under gravity – transforms into a nighttime shot of Niagara Falls, again bathed in colored light.

Gaillard performs the simplest yet most effective gesture of juxtaposition: a double collapse, a double spectacle – identical yet distinct, continuous yet ruptured.

On the opposite side of the wall constructed at the center of the gallery around which the exhibition’s narrative seems to revolve, the most recent of the three works, Ocean II Ocean (2015), is projected. The video takes us to three distinct locations: into the cars of the New York subway, the surface and depths of the Atlantic Ocean, and the corridors and platforms of the Moscow metro. Compared to the other videos on view, Ocean II Ocean is visually more intricate and, uniquely among them, accompanied by a dense and enveloping soundscape that effectively functions as the exhibition’s soundtrack.

The sequences filmed in New York’s subway were shot on a smartphone, yet the way they build tension – between the close-up of a window frame or the coupling rod between train cars and the shifting urban landscape that passes in the background – evokes the grainy poetics of experimental cinema. The loosely associative chain of images culminates in an abstract shot: a black surface glimmering with what appears to be a distant star. As the camera slowly zooms out, the “night sky” begins to resemble an enlarged pupil reflecting ambient light. Further zooming reveals that the scene depicts water swirling in a stainless-steel toilet bowl, just as it is flushed away.

A Duchampian moment, one might say, but simultaneously far removed. The reference here is not to the institutional critique of art itself, nor a comment on cultural hierarchies of high and low. Rather, the utilitarian vessel can be read as yet another apparatus of modernity, here reimagined as a distorted lens: not a telescope through which we gaze into the distance but one through which we peer into the depths of time.

Water is the exhibition’s leitmotif, metaphorically flowing from one work to the next. At times it appears as the absent element that once sustained the primordial bodies of mollusks; at others, as a mirror behind which the stark mask of modernity begins to peel away, revealing the corporeal, animal substratum of violence and pain. Elsewhere, it emerges as a natural spectacle subsumed within the tourist-industrial complex, where natural bodies are exploited no less than human ones. Finally, it manifests as a source of hygiene and purity – values upon which modernity so proudly rests – and also as a symbolic grave, into which decommissioned subway cars are sunk, to be slowly transformed over time, much like the ammonite shells that have fossilized into stone.

This brings us to the film’s second part. Here the subway cars are no longer seen from within but from the outside: empty shells stacked on the deck of a cargo ship, from which a mechanical arm lifts and releases them one by one into the sea. Subsequent underwater shots reveal these human-made vessels as they merge into the marine ecosystem. Schools of fish, larger predators, and majestic sea turtles glide through the skeletal frames. The ocean reappears in the final section, now within the subterranean passages of the Moscow metro. The camera lingers on the reddish stone tiles that line the walls; in their pale veining, one can discern the same spiral traces of ammonites familiar from the earlier works. Their distinct forms have endured for millions of years, preserved within the fossilized sediment of an ancient seabed.

Gaillard’s practice is remarkable in the way it fuses what, across the last two decades of contemporary art, have often appeared as two distinct preoccupations. The first is the “archaeological impulse” – a turn toward the past, or rather, a reading of the present through the lens of the archaeologist who discovers, within the ruins of modernity, not only evidence of a bygone faith in the future but also a mirror image of a present unable to imagine one at all. Gaillard’s work from the late 2000s resonated strongly with that of numerous artists from post-socialist Central and Eastern Europe, who, during that brief and luminous moment, found themselves in the field of vision of international curators, museums, galleries, and biennials. In one of his essays, Roelstraete famously described post-socialist Europe as an “exclusive archaeological site.” It should come as no surprise that Gaillard, too, ventured into this terrain in search of material for his work.

By the mid-2010s, however, this tendency had been overtaken by newer and more urgent concerns. A renewed focus on art’s relationship to the internet was quickly followed by the increasingly complex constellation of discourses gathered under the banners of object-oriented ontology, new materialism, and the Anthropocene. The last of these terms became a key concept for thinking about what constitutes the content and agenda of a significant portion of contemporary art today.

When we look at Gaillard’s oeuvre through the lens of this Anthropocene-aware art that has emerged over roughly the past decade, it becomes clear that the element of deep time – that alternate temporality tied to natural processes and nonhuman “bodies” – was present in his work from the very beginning. And it has never functioned merely as a backdrop against which the faster, more explosive dramas of modernity and its decline unfold.

From this perspective, one increasingly recognizes that the monumentality to which Gaillard’s work aspires – despite its apparent simplicity – is largely an effect of the visual and narrative convergence between the natural and the cultural. The anecdotal, even farcical actions of his human (and mostly male) protagonists – diving into shallow water, chugging a bottle of liquor, or engaging in brutal street fights – acquire, when juxtaposed with the stoic presence of natural elements (or of human constructions that, through decay, return to a state of material nature), the dimension of tragedy.

What Gaillard’s works notably lack, however, is the moment of catharsis – the resolution of crisis or catastrophe. In their stripped-down construction they remain open-ended, leaving catharsis to unfold on the level of individual reception. And in this regard, Gaillard’s art exemplifies a particular paradox of contemporary art: while acutely responsive to the conditions and anxieties of the present world, it remains in its very structure, “stuck” in the modernist mode of individual, gallery-based contemplation, which notably hardly ever translates into any action in the outside world.

A decade ago, contemporary art began to feature, with growing urgency, the anxiety of an imminent environmental catastrophe. We started to feel that “deep time” had solidified into a kind of enormous hammer poised above us, ready to strike with the brute force of natural disaster, ecological collapse, a planet on fire. Today, however, the horizon has shifted. We witness, on a daily basis, the erosion of political imagination: the normalization of war, the re-emergence of authoritarianism, the discrediting of democracy as an outdated form. The contribution of Hungarian politics, shaped by Viktor Orbán’s ideological project, to this broader development is not negligible.

While writing this text, I realized that the metro tunnels of Kyiv, where Gaillard shot footage for Desniansky Raion in 2007, have now become vital shelters against Russian missile attacks and drone strikes. Another eerie connection: when stepping off the train at Budapest Nyugati station and descending the staircase between platforms 11 and 12 toward the underpass that leads to a modern shopping mall, one can spot, in the red stone slabs lining the passage, the same ammonite fossils that appear in Gaillard’s shots of the Moscow Metro… It took time, and the act of writing this essay, to articulate what had been troubling me since I visited the exhibition. This is what I came up with:

It becomes increasingly difficult to focus on melting glaciers and burning forests when the prospect of armed conflict in Europe, or the steady replacement of representative democracy by regimes grounded in the impunity of executive power, feels ever more immediate. At first, visiting Ocean II Ocean – descending beneath the surface, immersing oneself in the metaphorical ocean – seems calming, as though entering a temple insulated from the world’s noise. Yet once we absorb the work’s message, we realize that this calm is not solace but the absolute indifference of nature to our existence. Nature does not give a shit about how quickly or by what means we destroy ourselves. That is our tragedy: that only we are conscious witnesses to the consequences of our own actions; only we can attempt to wrest some meaning from them.

Gaillard possesses the rare ability to reveal flashes of the sublime within what is otherwise the botched episode of one neurotic species that happened to arise on the planet’s surface. But I don’t think he seeks to persuade us that what we are doing has any inherent meaning. What he offers are ravishing images of catastrophe – and if any catharsis is to come at all, it must occur at the street level, with our heads once again above the surface and our noses scraped raw.

From the ruins of modernity, no renewed, improved version of its old promises has emerged, as many hoped around 2010. Instead, only new and more virulent mutations of its old fears and pathologies have been born: new nationalisms, new dreams of domination, new genocides. Will it ever be possible to look back on the bloodthirsty zombie mutation of modernity that is now taking shape and see it as a ruin; another failed project of the past? Perhaps, but it is difficult to imagine that such a vantage point will be available to the generation to which both Gaillard and I belong.

Cartridge. Photo: Dávid Biró. Image courtesy of Trafó Gallery, Budapest.

Half)” (nautilus shell, Ortofon Concorde cartridge), 2022, 05.09.25 – 09.11.2025, Trafó Gallery, Budapest, photo: Dávid Biró. Image courtesy of Trafó Gallery.

[1] Karel Císař, “Modernology: Art after Postmodern Art.” In: Between the First and Second Modernity. 1985-2012, VVP AVU, Prague 2011, 49-58.

[2] Dieter Roelstraete, After the Historiographic Turn: Current Findings, e-flux journal, Issue 6 May, 2009

[3] Dieter Roelstraete, The Way of the Shovel: On the Archeological Imaginary in Art, e-flux journal, Issue 4 March, 2009

Artist: Cyprien Gaillard

Curated by: Borbála Szalai, Judit Szalipszki

Exhibition Title: Ocean II Ocean

Venue: Trafó Gallery

Place (Country/Location): Budapest, Hungary

Dates: 05.09.2025 – 09.11.2025

Photos: Dávid Biró