Raluca Oancea

An anniversary edition marking a decade of uninterrupted cultural activity by the Art Encounters Association, the Bounding Histories. Whispering Tales biennial, inaugurated in Timișoara at the end of May 2025, attests to the power of art to transform and put a city back on the world map. At the same time, the event opens a space of entanglement and continuity, allowing for the transgression of any metaphysical dichotomy – body/world, visible/invisible, subject/object – as well as differences of gender, race, or political geography. This logic of continuity is supported not only by the curatorial concept but also by the profile of the two curators, Ana Janevski and Tevž Logar, authentic citizens of the world (kosmopolitai), difficult to reduce to a single nationality or place of dwelling, connoisseurs of Central and Eastern European art, while remaining closely connected to prestigious Western institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, and VOX in Montreal.

The title of the biennial, Bounding Histories. Whispering Tales, reinforces the hypothesis of continuity, extending across both cultural and spatio-temporal levels. Among the key concepts that stand out in this regard is the notion of the echo, subtly distinguished from mere repetition and explored on ideological, spatio-temporal, and especially historical levels, in a Benjaminian sense, as a form of spectral actualization of the past. The way in which the artistic projects reactivate the micro-histories of Timișoara, connecting them with parallel narratives from Eastern Europe or the Global South, recalls, in my view, Walter Benjamin’s critique of historicism and of reducing history to a mere succession of facts frozen in a linear, homogeneous time. The works of the 64 invited artists and groups thus demonstrate that history is not a continuous line, but a collection of destinal moments that can resonate again when summoned by the present. In line with Benjamin, history proves to be alive, and the past ready to merge with the present in an echo that is not a mere reflection but an act of illumination and critical reconfiguration. What returns in this process is not the past itself, but its resonance, awakened in a moment of crisis like the one we are living today, as the spectre of fascism and radical nationalism haunts the world, from Europe to the Americas.

As in previous editions, several urban spaces were returned to the community through art, demonstrating its ability to re-signify the identity of a place of dwelling, whether a former factory or a decommissioned garrison. In the phenomenological sense, we might recall, a place of dwelling is not merely an address on one’s ID card but rather a dense space where one feels most oneself: for an artist, the studio; for a teacher, the classroom; for a worker, the factory.

Bounding Histories. Whispering Tales thus initiated a novel archaeology of the three exhibition spaces – the Garrison Command (a former military building), Faber (a former factory), and ISHO Art Encounters (formerly a factory and kindergarten) – aiming to “brush history against the grain” [1] by reactivating a past whose echo the present is now ready to hear. We should remember that “to articulate the past historically does not mean to recognize it the way it really was”[2], a phrase which, taken literally, is emptied of meaning, but rather to allow the present to ignite certain latent layers of a past which, through this very process, is rewritten, gathering new valences and interpretations.

A remarkable example is the project My First Treasure (2025), created especially for Art Encounters by Alle Dicu, following a residency in Timișoara during which the artist explored the history of the area surrounding the Faber creative hub. More specifically, the project focuses on the Fabric neighborhood, a working-class nucleus inhabited since the interwar period by a diverse ethnic community (Germans, Hungarians, Romanians, Jews, Serbs), where, after the 1950s, numerous factories and workshops, such as “1 Iunie,” “Bumbacul,” “Guban,” and “Elba”, were concentrated. Among these, the artist focused on the “1 Iunie” textile factory, a major industrial pillar employing thousands of workers, mostly women, which played a crucial role in the neighborhood’s development, offering not only jobs but also a form of social structure. Through their labor, often under difficult conditions, many women in Timișoara achieved a measure of economic independence. Gradually, a supportive female community took shape, grounded in mutual aid and a shared sense of belonging to the same industrial rhythm.

What Alle Dicu directly addressed through her intermedial work combining film with poetry, is the crisis experienced by these women following the bankruptcy and disintegration of the factory in the 1990s: the nostalgia for the collapse of the social network that once supported them, the disorientation and loneliness they faced. To this end, the artist proposes a three-dimensional spatiality in the form of a panopticon, where a series of televisions are arranged in a circle, like eyes that both watch and are watched in return, like cells under the surveillance of a virtual, invisible eye. In addition, the screens follow a female figure as she slowly moves through a ghostly building, its empty balconies echoing the same circular geometry.

But the punctum of the work is not the woman walking or absentmindedly smoking, withdrawn in a white robe, but rather the black dress she has hung out to dry in the dark night. As the artist herself notes, the project draws an analogy between the post-communist tragedy of the Timișoara textile factory and the painful transition of the Republic of Moldova to savage capitalism. This parallel is built from a scene in Tatiana Țîbuleac’s novel The Glass Garden, in which a poor child watches with fascination as clothes freeze on the line in the harsh winter air, secreting a (first) “treasure” of thousands of droplets sparkling like diamonds.

The simple act of hanging freshly washed clothes out to dry, the cathartic effect of the frost, initiates a poetry of purifying rest, of repose given form, of starched laundry imbued with the scent of winter and fine iridescences of snow. All these subtle clues can be retrieved from a separate 1:1 video close-up accompanying the film footage: a portrait of the same black dress, frozen in time, covered with tiny glittering crystals – readable, perhaps as an ocean dress illuminated by waves or as a clear sky in the polar night.

It is here that we perceive, in full force, the same delicate poetry of everyday life that inspired an entire wave of neorealist filmmakers, beginning with De Sica, who in Umberto D. filmed with infinite care and patience the unspectacular life of Maria the housemaid: her modest waking ritual, small gestures like striking a match on a wall, contemplating a cat on the roof, the pensive touch of her own belly hiding the pregnancy that would cost her employment. From such images, Bazin theorized the fact-image: an unspectacular, contemplative representation that lays bare the temporal flow as experienced by each of us: like a river, like a protective blanket, like a continuous current unbound by causality, impossible to capture in a linear narrative driven by action and hurried along by dramatic intrigue.

Another work produced specifically for the Art Encounters Biennial 2025 is Apparatus, an installation made of birch plywood, glazed ceramic, soap, putty, and steel, in which artist Lorena Cocioni situates herself within the same territory of continuity and interference between visual arts, design, and architecture.

Also installed in the Faber space – a former oil and soap factory – the work introduces a massive silhouette with a ceramic skin and metallic tentacles, initiating a discourse around rituals of washing and the notion of intimacy. Inspired by the interiors of French bathrooms from the 1970s – a unique blend of functional modernism, pop influences, and a touch of domestic extravagance in warm, psychedelic colors – the ceramic tiles adopt not only unusual hues but also unconventional forms: irregular hexagons, organic shapes that evoke the world of microorganisms more than aseptic, perfect geometry. This universe, with space age influences and retro-glam accents, questions the multiple roles of design as both a binding agent and a catalyst for the transformation of industrial, social, or personal spaces.

A binding role, this time between the three exhibition spaces of the biennial, was also played by the series of events staged by Manuel Pelmuș in each location. This endeavor involved a performative reimagining of Croatian artist Mladen Stilinović’s work Two Times / Dva Vremena, following the well-known model of immaterial retrospectives presented in Venice (2013). The resulting performance, in which a human actant lies horizontally, almost motionless, occasionally turning, thus suggests the convergence of two distinct temporalities: the linear time of labor and the cyclical time of rest, raising questions such as: What is the value of inactivity? Can rest become a political and aesthetic gesture?

In this context, both the critique of the imperative of movement and speed advanced by André Lepecki in Exhausting Dance, and Stilinović’s Manifesto of laziness – in which he rejected the Western model of the artist as a producer of tangible objects for the gallery and auction house system – are evoked. Through this performance, Pelmuș reconfirms the ongoing reconfigurations of art that blur the boundaries between dance, installation, painting, photography and performance. He also aligns his work with a paradigm centered on phenomenological laziness (which identifies the human with time) and critical immobility (in which the performer’s body resists the flow of movement and its association with capital flows or the illusion of progress).

We can interpret all of this as an interference between performative immobility and the critical economy of art, one that uses sleep as both a form of labor and an act of resistance to capitalism, inviting reflection on time, value, production, and rest. At the same time, the project activates a Benjaminian reading, in the spirit of a critique that exposes the attempt of fascism and, in particular, National Socialism, to appropriate and re-signify the concepts of labor and progress for its own ends. More broadly, the biennial as a whole aims to reveal the conceptual complexity of labor, beyond the reductive paradigm of quantity and production.

We now move to the second space of the biennial, the Garrison Command: a military building interpreted by the curators as a site of convergence between history and political authority, strategies of normalization and control, as well as numerous movements of resistance and dissenting voices against colonialism, imperialism, and systemic violence. A representative project for this space is Ana Adam’s large-scale textile work; a comic strip embroidered with silk, metal threads, and beads, which reactivates hidden stories centered on two protagonists significant to the premodern history of Europe and the Banat region: Prince Eugene of Savoy and Count Claude Florimond de Mercy, a key promoter of the garrison building’s construction. In line with the spirit of the biennial, the artist approaches history not as something to be admired from a distance, but as something to be lived and internalized – a series of still-vivid moments that can be reinterpreted and enacted.

Drawing from a historical archive that reveals not only the queer persona of the Prince of Savoy-Carignan – hero of Christendom and lover of jewelry and dresses – but also biographical details about his relationship with Count Claude Florimond de Mercy, the artist constructs a personal narrative. The archives show that in 1716, at the time of the conquest/liberation of Timișoara from the Turks, the two had already been fighting side by side for over 30 years and shared a deep interest in animals and plants. These elements are woven into an imaginary dialogue with the two men, articulated through silk-embroidered messages such as: Dear Claude, I dyed my dress with the Rubia tinctorum you sent me! or Mon cher Claude, how countless the mulberry trees planted are![3] The tone is playful and intimate, softening the militarist-imperialist rigidity that so often shrouds historical narratives. At the same time, these messages gently mediate the transition from the myth of “Little Vienna” to the Timișoara in which the artist lives and works today. This temporal and spatial play reactivates a Benjaminian interpretation of historical echo – as a metaphor for survival and the fragmentary reappearance of the past in the present. Refusing to be “a structure whose site is homogeneous, empty time,”[4] history here calls forth what Benjamin described as Jetztzeit – the now-time – a rupture in the normal flow of temporality, in which a past saturated with “nows” meets a critical, dense present, capable of transcending linear chronology.

Ana Adam’s playful subversion of dominant narratives aligns with a broader trend among contemporary archivist artists who generate possible scenarios and alternative histories starting from vernacular or institutional collections, thereby undermining official memory. This working method draws on Derrida’s research,[5] which exposed the subjective nature of official history – the alliance between power, the guardianship of documents, and the writing of history – as well as the archive’s role as an active and regulatory discursive system.

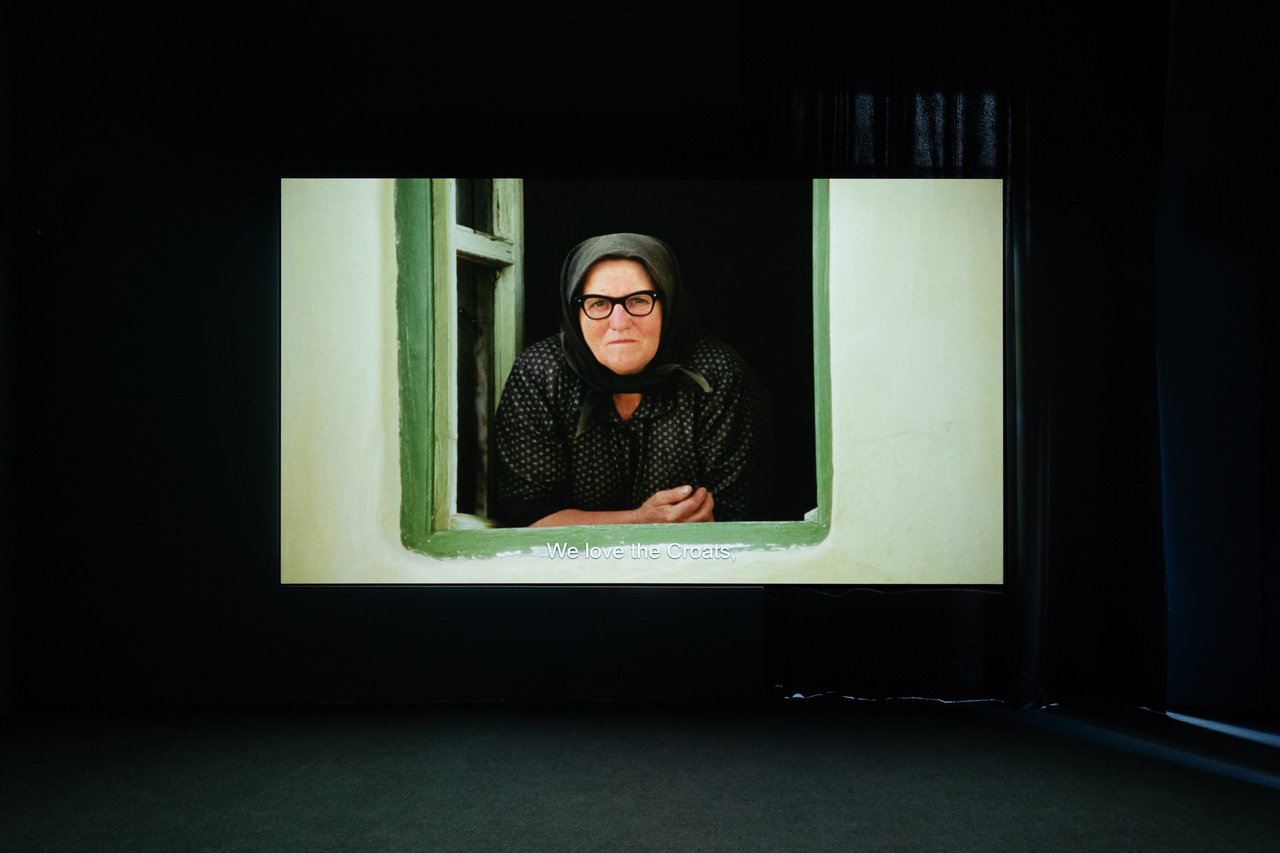

At Art Encounters, the echoes of unrest and protest reverberate through an extensive series of works that bring to the forefront the identity stories of various ethnic groups and uprooted individuals, emphasizing both their resilience and the impact of migration on personal and collective histories. Ghenadie Popescu explores, in his suggestive video In-between (2010), filmed from above, the condition of Moldova as well as that of the contemporary artist trapped in a claustrophobic transitional space, caught between doors opened and closed at will by the chosen few. Karpo Godina presents, in the 35mm film Healthy People For Fun (1971), a collection of vividly colored postcards depicting scenes from the lives of various ethnic communities in Vojvodina, where people’s stories, shaped by history, ritual, and tradition, reverberate in the domestic space.

Ana Kun dedicates her conceptual poems, white-on-white and unrhymed, to those deprived of privilege, political, or artistic visibility — to those whose labor remains perpetually in the background. In the exhibition, she contributes two works: a visual poem and a textual poem. The visual poem, No One Has What They Deserve (2022), consists of a photograph showing the artist from behind, dressed in a white blouse into which the titular words have been subtly unraveled. Barely visible against her pale skin, the phrase resists readability, echoing the erasure and marginalization it addresses. This work is paired with a second piece: White (2022), a printed poem installed directly on the exhibition wall. Composed of sparse, blank, protest-like lines, the poem condemns systemic racism, particularly the kind directed against Roma communities, and resonates with the spoken-word performances of Romanian poet Elvisey Pisică. Together, the two works form a quiet but persistent demand for justice and recognition.

The same manner of visual poetry, both delicate and radical, is explored by Raluca Popa in the installation Poem (2023), which brings together four lenses of different sizes, mounted on a wooden board, and a series of cardboard strips bearing verses from Love Songs, the debut volume of the Berlin-based Turkish artist Seda Mimaroğlu (“Keep coming. To gawk at something that is dead? / Why keep coming back to this imaginary place / Why the need to reconstruct a moment / That was catastrophe.”). Inspired by the optical principles of the Rochester Cloak experiment, the installation requires the viewer to position themselves at a precise vantage point between the lenses, where fragments of text disappear completely from the visual field. The emphasis onplace, as well as the process of the text’s disappearance, speaks to the fragility and subjectivity of meaning and memory, evoking themes such as the redefinition of dwelling in a world marked by migration and globalization, uprootedness and invisibility, experiences that Raluca Popa, who herself relocated to the vast Berlin metropolis, has lived firsthand.

At this same intersection of the color white and conceptually driven, socially charged poetry, lies Larisa Sitar’s project Robust Boast (2022). It consists of a series of discreet white bas-reliefs, mounted on equally white walls, placed in unexpected positions: either very low or far above eye level, always in dialogue with architectural elements such as narrow corridors or windows embedded in the garrison’s thick masonry. For those with the interest and patience to discover them, the works reveal a visual inquiry into how post-1990 housing in Central and Eastern Europe reintroduces ornamental features from (neo)classical styles – columns, busts, bas-reliefs with anthropomorphic or vegetal motifs.

The absence of color and the clean geometry of form place the endeavor at the crossroads of classical sculpture, architecture, and conceptual art, in perfect harmony with the overarching concept of the biennial. A graduate of the Photo-Video Department of the National University of Arts in Bucharest, Sitar approaches art through the lens of a contemporary continuity that transcends genre, medium, and discipline.

Her research navigates complex intersections between the social, ethical, and aesthetic, reactivating and connecting successive moments from the histories of art and architecture, beginning with modernism’s rejection of ornament and sentiment in the early 20th century. The critique of ornamentation (whether architectural, decorative, or ritual), denounced as wasted labor and aesthetic degeneration by architect Adolf Loos (“Ornament and Crime”, 1908), resonates here with Clement Greenberg’s condemnation of kitsch as a double affront to aesthetic value and authenticity (“Avant-Garde and Kitsch”, 1939). Opposed to both, however, stands the postmodern defense of sentiment and decoration, as exemplified in Susan Sontag’s essay on camp (“Notes on Camp“, 1964).

This layered confrontation – between past and present, between digital techniques and traditional forms – situates Sitar’s work outside of linear time, within a continuous present of the Jetztzeit kind, or even in a state of nunc stans (the “eternal now” of divine time, in Saint Augustine’s thought). Paradoxically, the work remains deeply socially engaged, asking: If in 1939, kitsch targeted the mass-produced, garish object through which the bourgeoisie simulated aristocratic taste and consumed pleasure without effort, how should we understand the return of ornament after 1990? In the post-socialist context of Central and Eastern Europe, is it a desire to realign with the genetic code of the West? Or the nostalgia of a generation that blends decorative elements in the visual grammar of elevator music and Vaporwave videos – where a Photoshopped bust of Apollo floats above the simulacrum of a sunset on a Windows 95 desktop?

A final thread present at the Garrison Command is the entangledrelationship between humans, nature, and the earth. In a phenomenological reading, the earth cannot be reduced to mere soil or site, instead, it represents that hidden dimension of nature, elusive to scientific measurement and accessible to humans only through art. Human dwelling, in this sense, requires a deep attunement to natural elements – sky, earth, and their interplay.

This interpretive lens allows us to revisit Geta Brătescu’s iconic performance Earthcake (1992), in which the artist eats and becomes one with the earth, alongside echoes of the ancient Greek concept of nature – physis – revised by 20th-century phenomenology and brought back to the fore by the ecological crisis. In the exhibition, Earthcake is presented alongside a recent response: Positive-Negative (2016–present) by Canadian artist Kapwani Kiwanga, a participatory installation that blurs the boundaries between art, labor, and environment. Using a bucket and handcrafted ceramic tools, visitors are invited to transport a layer of soil from the gallery back to its original site in the garrison courtyard. Here, the earth becomes an agent of reflection on extractivist practices, the uprooting of communities, and the layered histories that shape both Timișoara and broader sociopolitical geographies.

The echo of the earth leads us to the final venue of the biennial, ISHO Art Encounters, where, among other significant works, we encounter the film Semiya (2015) by Cecilia Vicuña, the Chilean poet, activist, and visual artist who, as early as the 1960s, coined the concept of precarious art. This video poem offers a poignant meditation on ecology and memory, dedicated to the endangered seeds from the foothills of the Andes; symbols of resilience, continuity, and ancestral knowledge. The act of gathering becomes an intimate gesture of resistance against the degradation of both nature and culture, the work resonating gently yet powerfully with the broader themes of the biennial. In this context, the notion of the echo prompts a deeper inquiry into the relationship between art, history, and nature in cities marked by layered political and social transformations, such as Timișoara or Santiago de Chile.

The circle closes, and the echo leads us back to Faber, and again to the Garrison. In a city shaped by overlapping histories and personal trajectories, the echo of art reactivates the past not as relic, but as a living force. In Derrida’s terms,[6] this is not a matter of mechanical repetition but of active reverberation, a form of différance, involving both difference and deferral. Thus, the works in the biennial do not merely invoke history; they bring it into the present, forging a living dialogue between memory and transformation.

Translated by Dragoș Dogioiu

[1] Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Thesis VII.

[2] Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Thesis VI.

[3] As the artist points out, Count Claude-de Mercy had ordered the planting of dye plants in Banat, including this one which produces a red color, essential for the textile industry he had initiated. He had also ordered the planting of 143,000 mulberry trees, necessary for the silk industry he established here, alongside other crafts.Art Encounters Catalogue, 2025, p. 76

[4] Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History“, Thesis XIV

[5] Derrida, Jacques, Archive Fever. A Freudian Impression, The University of Chicago Press, 1998

[6] Derrida debates the idea of the echo in the essay „La différance”, 1968.

Artists: Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Marina Abramović, Ana Adam, Bora Baboci, Maja Bajević, Mona Benyamin, Zeljka Blakšić, Pavel Brăila, Geta Brătescu, Dayrit Cian, Marieta Chirulescu, Christine Cizmaș, Clément Cogitore, Lorena Cocioni, Alle Dicu, Moriah Evans, Simone Forti, Robert Gabris, Alicia Mihai Gazcue, Ladislava Gažiová, Jean Genet, Liam Gillick, Maria Guțu, Petrit Halilaj, Veronika Hapchenko, Hassan Khan, Loredana Ilie, Joan Jonas, Godina Karpo, Dana Kavelina, Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński, Kapwani Kiwanga, Ana Kun, David Maljković, Jumana Manna, Teresa Margolles, Silvia Moldovan, Oscar Murillo, Andrei Nacu, Marina Naprushkina, Eduardo Navarro, Christian Nyampeta, Mila Panic, Manuel Pelmuș, Gavril Pop, Raluca Popa, Ghenadie Popescu, Larissa Sansour, Ștefan Sava, Selma Selman, Siniša Ilić, Larisa Sitar, Franko Jošt, Hopinka Sky, Bojan Stojčić, Nora Turato, Ulay, Johanna Unzueta, Mark Verlan, Cecilia Vicuña, Anton Vidokle, Rosario Zorraquin

Curated by: Ana Janevski, Tevz Logar

Exhibition Title: Art Encounters Biennial: Bounding Histories. Whispering Tales

Place (Country/Location): Timișoara, Romania

Venues: Garrison Command, FABER, Art Encounters Foundation, Jecza Gallery

Dates: 30.05 – 13.07.2025

Photos: Remus Daescu, David Dumitrescu