Dalma Pszota

Debrecen, historically referred to as the “Calvinist Rome” or the “Civic Town” of Hungary, has a deep-rooted botanical tradition, from the herbarium, which houses the documentation of Hungary’s medicinal plants by 16th-century scholar Péter Melius Juhász, to the Magyar Füvészkönyv (1807), the country’s first botanical book, co-authored by Debrecen-born Calvinist pastor Sámuel Diószegi and poet Mihály Fazekas. The city is also home to one of Hungary’s oldest protected natural areas, the Great Forest (Nagyerdő), and the Debrecen Botanical Garden which preserves thousands of plant species. Despite having a unique blend of history, science, and botanical beauty, Debrecen remains on the periphery of the art world, making the project and exhibition explored in the following text all the more intriguing.

The city’s strong connection to botany was likely on the minds of the organizers of the Debrecen International Artist in Residence (DAIR) program in 2024 hosted by MODEM, for which the exhibition Learning from Nature? – Botany was produced. As part of the program, DAIR hosted a two-week intensive workshop in Debrecen during the summer of 2024, bringing together both Hungarian and international artists and curators.

Needless to say, this short period was probably not enough to fully grasp the complex historical, contemporary, botanical, and environmental context of the venue. However, it did allow artists to expand their existing practices by engaging with the local context – specifically, Debrecen’s botanical heritage and what it can teach us, or, more precisely, what we can learn from nature, as the exhibition’s subheading suggests.

In this essay, I attempt to reflect on the questions raised by the exhibition itself: Can we really learn from nature? If so, what can it teach us, and how? What even counts as “nature”? And are we already too influenced – or maybe even stuck – by our own ideas and assumptions?

Botany and Beyond: Unfolding Narratives

Entering the exhibition, we find ourselves inside a giant red flower-like womb, or tent, by composer Bálint Szabó. The installation, Through Shimmering Voices They Speak, welcomes visitors with an almost visceral effect, stirring a deep, instinctive response, preparing them for a shift in mindset. The polyphonic ambience acts as an immersive ritual of symbolic cleansing, encouraging us to clear our thoughts and open our hearts to the wisdom embedded in nature. The installation evokes the phenomenon known from ethnographic literature as the “sacred flute complex,” channeling it through the fictional Kamenawai tribe, imagined to inhabit the region centuries into the future.[1]

The installation questions whether a culture can be understood solely through sound, while also critically examining the visually-driven presentation methods of contemporary ethnographic museums. No instrument is physically present in the “womb” – only the sounds themselves. The visitor is left to interpret what these auditory traces might reveal.

This artwork provides a crucial moment of reflection, shedding light on our specific cultural and societal positions, encouraging us to question them. This artwork operates as a transition from the street to the exhibition space that initially prepares the visitor to gain new perspectives on nature, botany, climate change, and the region’s history.

From this point, the exhibition is divided into three sections, each exploring different aspects of climate change, botany, and human-nature relationships. The first section, “Ecological Niches, Anthropocene Landscapes, Feral Grounds,” examines shifting ecosystems and human-altered environments. The second, “The Metamorphoses of Natural Symbolism,” reflects on how nature has been represented and reinterpreted across time. The third, “Speculative Organisms and Econarratives,” delves into alternative ecological narratives. While these divisions suggest that the works fit neatly into categories, in reality, they exist within a far more intricate network of connections. Rather than rigid classifications, I see them as threads in an interconnected web, collectively addressing the environmental and regional issues at the heart of the exhibition.

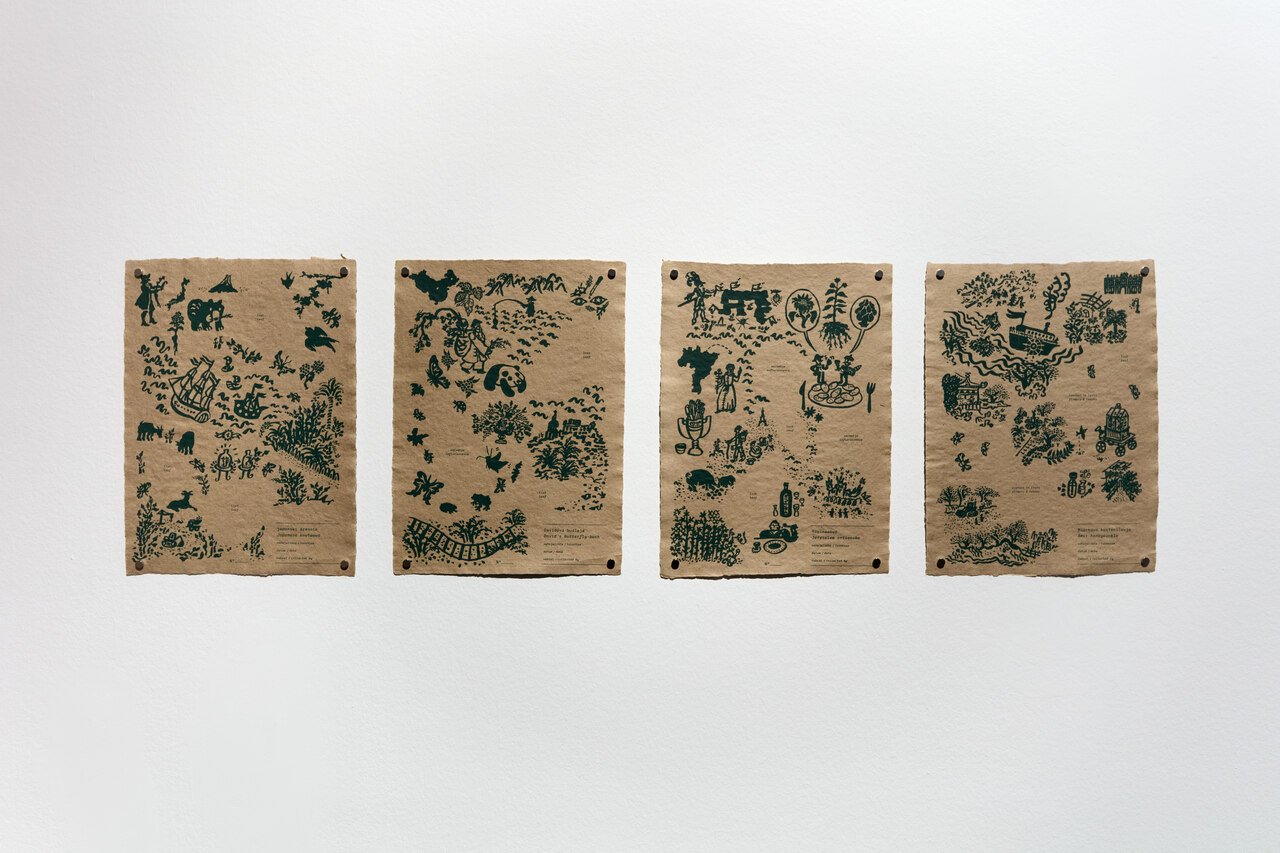

Going further into the exhibition, we encounter the ecologically conscious, Ljubljana-based Krater Collective, whose work is centered around a specific site – an actual crater in Ljubljana. This biodiverse space has inspired the collective to transform it into a laboratory where they explore ways to rethink anthropogenic ruins and examine the past and future of invasive species, considering their potential role in fostering a regenerative urban environment. In the context of urban renewal, the group’s representative at DAIR, Gaja Meznarič Osole, applied their regenerative vision to Debrecen, envisioning a project that builds on their earlier initiative, Future Scenarios. This Debrecen-based utopia incorporates the widely invasive tree of heaven (Ailanthus altissima), proposing to plant it in boxes near the museum’s entrance to create a sustainable habitat for eri silkworms – potentially increasing the local butterfly population. Even though the motivation to reframe the discourse about invasive species is an important initiative, the work presented in Debrecen overlooked the specifics of the local ecosystem. This introduction could further destabilize an ecosystem already in transition due to climate change (drought) and human activity (a planned battery factory nearby). Such an approach might be unethical and overlooks the most important principle: to know, respect, and work with the inherent characteristics of the environment.

They also present other sustainable practices already in use in Ljubljana, such as the creative reuse of found and natural materials – for example, papermaking, which does not necessarily go beyond what is already common among ecologically conscious collectives. The project attempts to apply methodologies that have already succeeded in Ljubljana, but it somehow misses the main point: understanding and adapting to the specific ecological concerns of Debrecen and its region. We cannot think about the future in general utopic terms – we must understand local contexts in order to build a strong and durable network of diverse species, including humans.

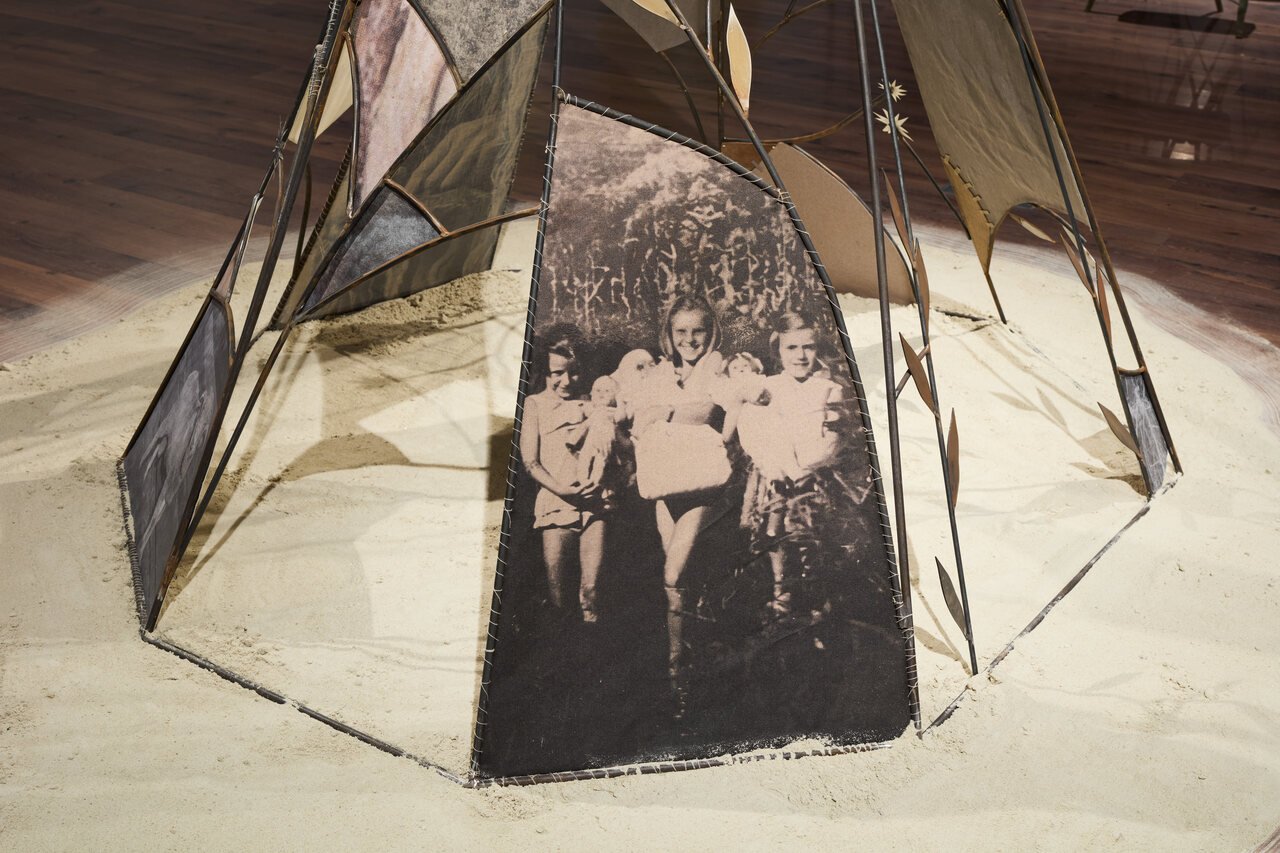

The next installation, Mirage, by artist duo Katalin Kortmann-Járay and Karina Mendreczky, weaves a symbolic myth from fragments of historical fact and imagination. The setting sun wallpaper, sand and weeds on the floor, fragmented plants and insects, traditional clothing, and photographs create a layered, dreamlike vision of landscape, blending the familiar with the unexpected.

Nostalgic landscapes and a sense of melancholic longing frequently appear in the duo’s work, and they employ these elements here as well to explore or even create the(ir) private mythology of the Debrecen area. Their work sensitively captures the intersection of cultural memory, personal narratives, and the shifting relationship between humans and nature. The installation subtly reveals the constructed nature of the Hortobágy[2] landscape, demonstrating how cultural, social, and natural forces have shaped its present form.

Wild Water Country is an installation by Zsófia Szonja Illés, comprised of a short video, a documentary, and two sets of objects: a natural-dye textile installation and a “walking table” with “walking stools.” These elements reflect on the notion of usefulness versus uselessness, as the furniture is crafted from false indigo bush, an invasive and notoriously difficult-to-eradicate plant. The natural-dyed textiles further highlight the ecological diversity of the floodplain area, as they were dyed with the flowers and plants collected in the area, and their hanging installation evokes the real arrangement of the vegetation in the area. The most compelling aspect of the installation is the interview-based documentary, which traces the stories and experiences of floodplain farmers along the central stretch of the Tisza River. Through these conversations, the work reveals a rich yet gradually disappearing tradition of animal husbandry, plant cultivation, and land use, offering a nuanced perspective on the causes and consequences of ecological and societal change.

Up to this point, it may be noted that none of the works have been directly tied to botany. It is through Eszter Júlia Kuzma’s installation, The Touch of Innocence, that we are brought into the world of plants directly. The piece consists of a colour-changing magical sphere and a hand-embroidered fabric tent depicting the wild myrtle plant, inspired by Katalin Széchy’s wedding shawl from the Collection of the Reformed College of Debrecen. This botanical motif is not merely decorative but carries historical significance, referencing the traditions of Vojvodina-Moldova villages, where red symbolizes modesty and white represents shamelessness. The tent and the sphere refer to different traditions and the meaning of the colours is supposed to create a space where conventional cultural meanings and interpretations are confused, reversed, and liberated.

Through its engagement with tradition, symbolism, and gendered roles, it is clear that the installation attempts to weave together multiple layers of meaning. Yet, within the exhibition space, its intricate network of references seems to struggle to fully assert its own voice, and it is not clear what the touch of innocence referred to in the title actually is in this context.

The last piece in this section is Meteorici Diagram by Centrala Architects. The work features a wooden plank reminiscent of Hungarian Calvinist church ceilings, painted with various meteoritic flowers. These flowers, whose petals open in response to atmospheric changes, serve as natural indicators of shifting weather conditions, relying more on meteorological variations than time of day. This categorization is based on the classifications of Carl von Linné (Carl Linnaeus), Swedish botanist and founder of taxonomy. The piece pays homage to the decorative traditions of the Reformed churches in Northeastern Hungary while intertwining scientific observation with cultural heritage.

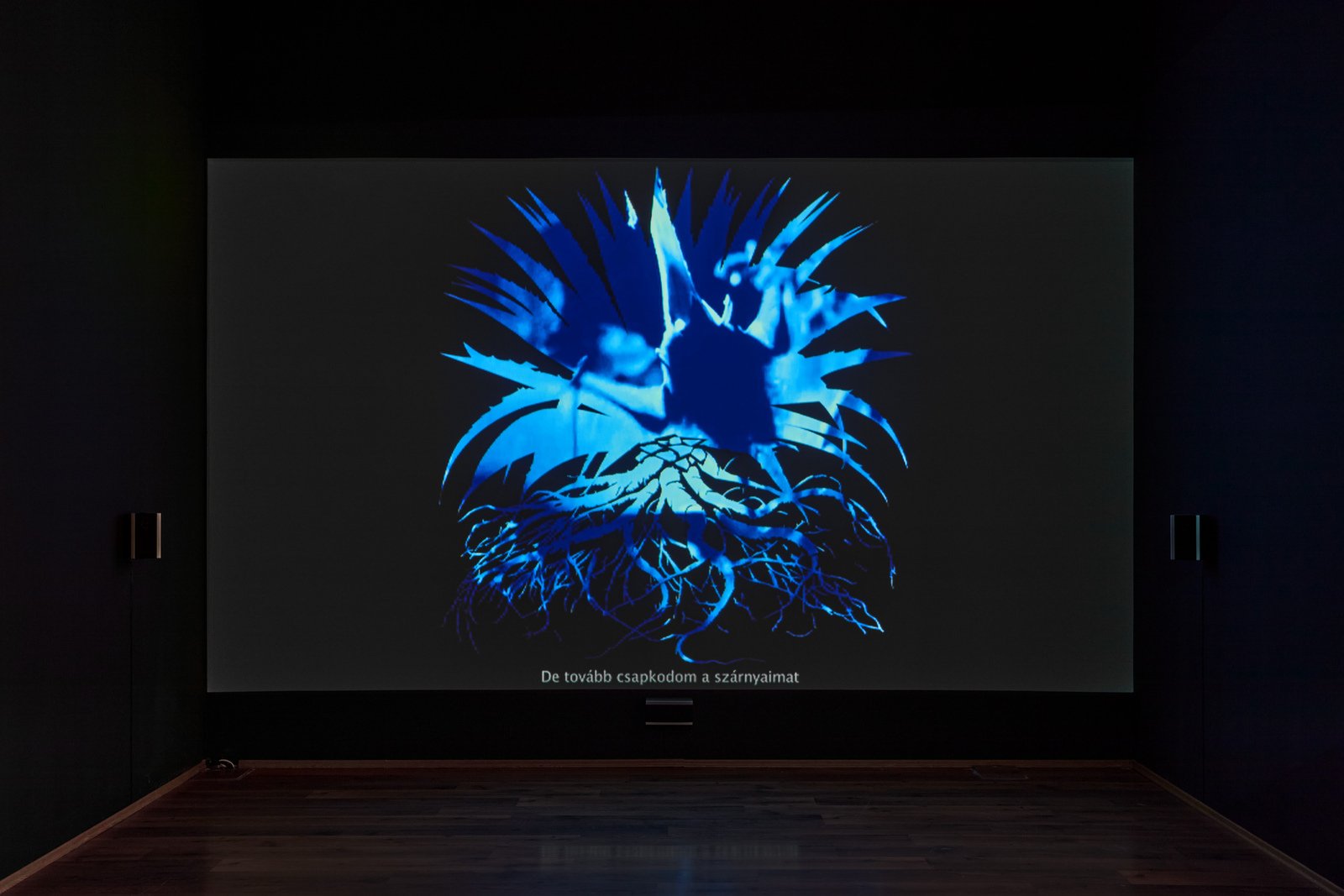

The next artwork beautifully exemplifies the connection between Debrecen’s botanical heritage and the artist’s own botanical references from their home country of Mexico. In the video The Night Will Come, Daniel Godínez Nivon captures a magueyero bat drinking nectar from maguey blossoms, its wings leaving a shimmering trail of pollen against the night sky. In the background, a sweet love song plays, written and recorded by the artist in collaboration with the descendants of the Tlachiquero from the Nahuatl indigenous culture. This tribe has a deep connection to the maguey plant, as the honey water extracted from it is used to ferment their traditional drink, pulque. The work was inspired by the artist’s discovery of a maguey plant that once grew in the botanical garden of the University of Debrecen, encountered during the residency preceding the exhibition. The song, which speaks of longing and displacement, takes on an added layer of meaning as it reflects on Mexico’s colonized past. Through this connection, the work bridges personal and collective histories, intertwining themes of botanical heritage, cultural identity, and resilience.

Dorottya Vékony’s UV acrylic photo installation, Extended Blooming, explores the complexities of plant reproduction and the transition between the natural and the artificial. As insect populations decline, human intervention becomes increasingly necessary, whether by making plants more attractive to pollinators or genetically modifying them for survival. These genetic modifications raise ethical concerns, prompting us to confront uncomfortable questions about what we define as “natural” and “artificial,” and where the boundary between the two begins to blur. The hacked plant portraits – making the plants more attractive for insects by genetic modifications – printed on plexiglass, are translucent. The pictures are mounted away from the wall, and the transparent plexiglass allows light to pass through, casting subtle shadows onto the surface behind, creating a layered visual metaphor for these dilemmas.

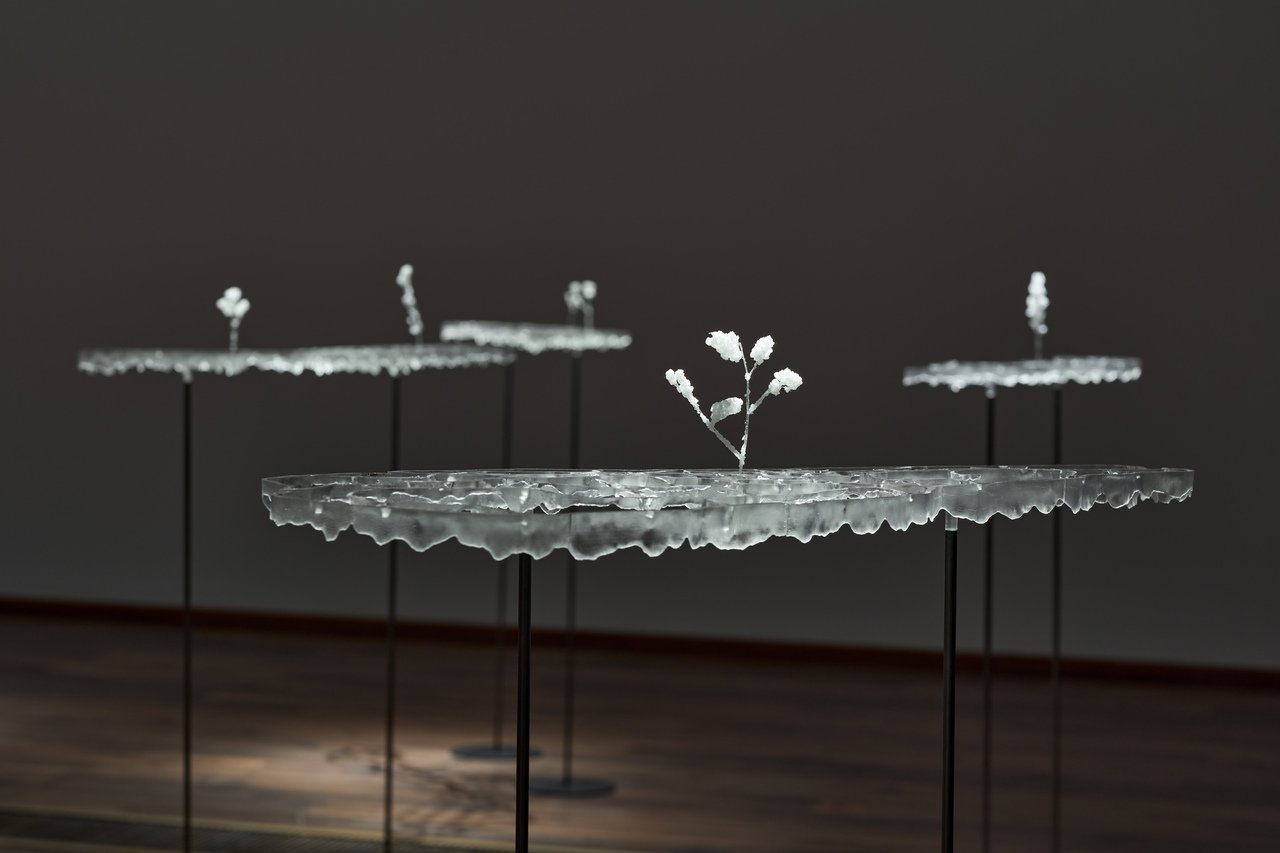

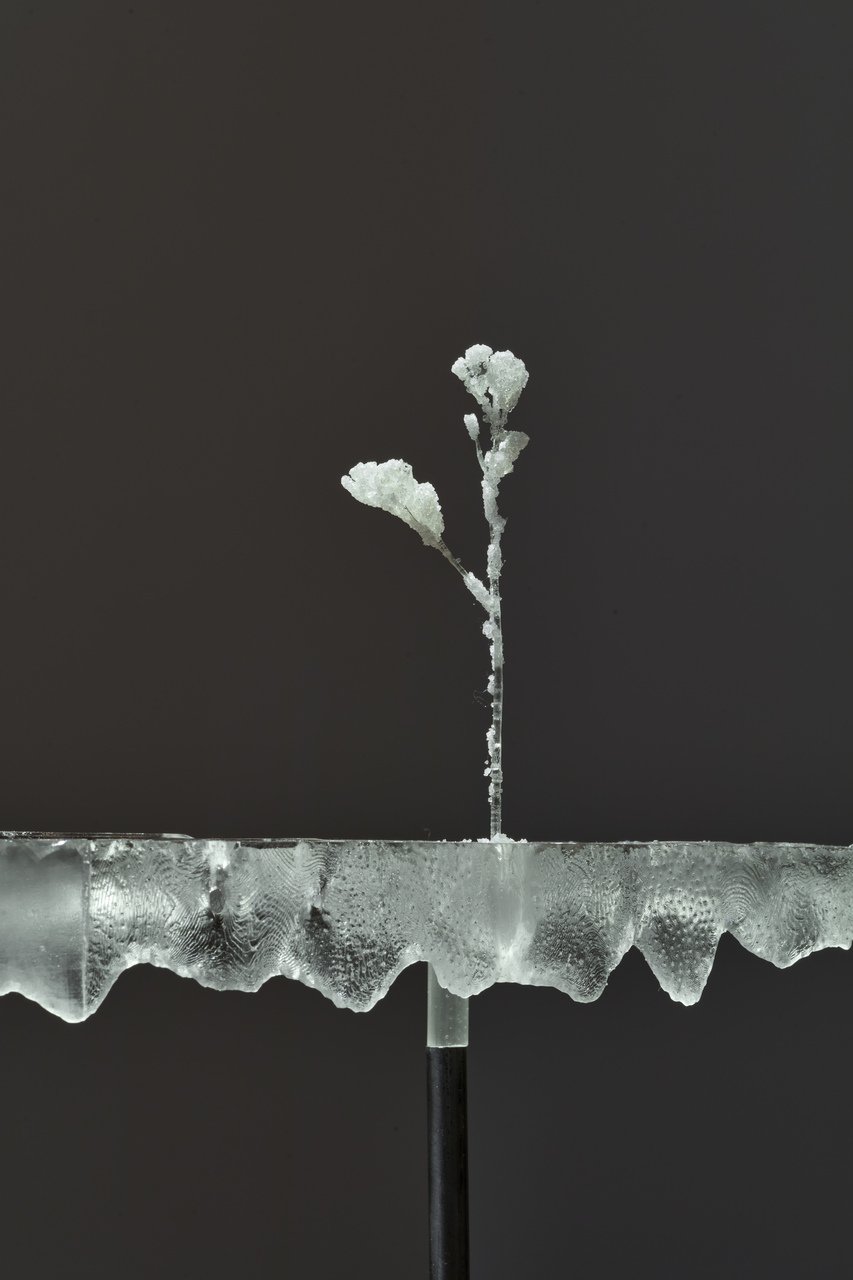

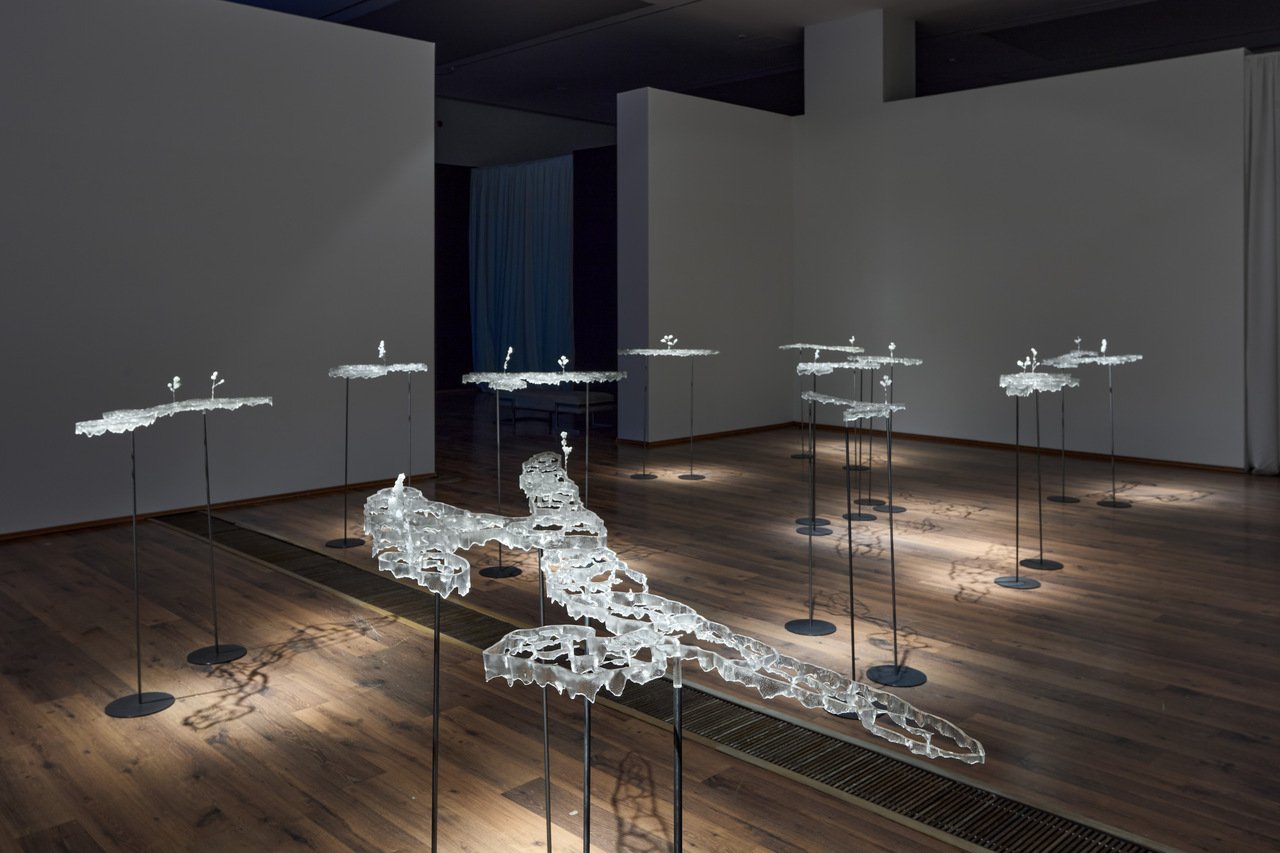

Nóra Szabó’s installation, Salt Ridge: On the Border of Two Worlds, represents a frequently occurring phenomenon of the Hungarian Great Plain – salt ridges – where the close interweaving of living and inanimate elements becomes visible.

In the exhibition space, translucent, mosaic-like 3D-printed islands with irregular shapes evoke naturally formed landscapes. However, their ghostly white hue and delicate crystal flowers blooming on them lend an eerie, otherworldly quality to the installation. The figures are inspired by rocky outcrops, a geological feature of the Hortobágy forest. Due to the high salinity of the soil, these outcroppings act as natural water reservoirs while the surrounding, vegetation-free land erodes, leaving behind isolated islands.

The final artwork in the exhibition is Thea Lazar’s Pressed Leaves and Brittle Petals, a two-channel 3D video installation that revives the traditional practice of flower pressing. One channel features a book displaying excerpts from Emily Dickinson – both an herbarium and a poem – while the other follows a camera slowly moving across a field of wildflowers. The work explores the act of flower pressing and personal memories attached to it, while also emphasizing the importance of understanding our environment and its flora. Its sentimental tone evokes a romantic contemplation of transience, with flowers serving as both indicators of change and vessels of memory.

Can We Really Learn from Nature Here?

Leaving the exhibition, visitors may still grapple with the questions raised earlier. The exhibition’s title suggests that we should learn from nature, yet it never clearly defines what “nature” actually is. While this ambiguity could allow for a broad range of interpretations – acknowledging that nature can take many forms – the exhibition texts often assume a rather naive relationship between humans and the natural world. Nature is framed as something idyllic, beautiful, and innocent. But that is a simplification. Nature is not only the flora and fauna surrounding us but a complex system of all living beings, including humans, trees, elephants, bacteria, and fungi.

Despite this oversimplified perspective in the texts, the artworks themselves engage with nature in a much more nuanced way. They draw on historical contexts that shape our present, exploring both the losses and gains brought by ecological and climatic shifts. Crucially, they recognize that humans are not separate from nature – our actions are deeply entangled with the very systems we seek to understand.

What I also missed from the exhibition was a reflection on the shifting perception of nature – from the birth of the first herbarium in Debrecen, through the Industrial Revolution, to the present. In their essay Getting Entwined: A Foray into Philosophy’s and Art’s Affair with Plants, Giovanni Aloi and Michael Marder explore how philosophical traditions – from The Bhagavad Gita to Plotinus – have long understood nature as an intricate, entangled system. Rather than existing as an external, harmonious entity, nature is deeply embedded in the structures of knowledge, existence, and human thought. The essay further elaborates on the anthropocentric foundations laid by the Bible, which have shaped our approach to natural resources.[3] A similar interpretation of the evolving perception of nature throughout history would have enriched the exhibition.

Mentioning another important historical reference, the relationship between botany and colonialism – briefly touched upon in the exhibition text about Daniel Godínez Nivon – would have added an intriguing layer to the exhibition. Exploring the colonial dimensions of botany, we encounter a range of questions that connect to the artworks, even if they are not explicitly articulated. In the context of Godínez Nivón’s work, colonization refers to the “stolen” plant species transported to Europe, while the places of their origin – and the cultures of the people who lived there – were completely and irreversibly transformed. In the Hungarian context, we might also reflect on the people whose ancient knowledge of plants and animals laid the groundwork for later scientific systematization. Reflecting on humanity’s past and present impact on our surroundings – whether living or non-living – can evoke a sense of consciousness that connects global actions to individual behaviour.

The next question raised by the exhibition is whether we can truly “learn from nature.” Contemporary art is undoubtedly an effective tool for thematizing and visually or sensorially depicting various environmental issues, as well as presenting coping mechanisms, methodologies, and strategies for both humans and non-humans alike. But, does the exhibition offer practical strategies or tools for co-existing with our surroundings? Or is it simply a showcase of artists engaging with environmental issues, leaving the message as one of education rather than offering actionable insights or pathways to coexistence? It raises more questions than it answers. Hopefully, the exhibition will achieve its goal and not become just another ecologically conscious show that becomes familiarized and normalized in its representation, failing to push us to become catalysts for change by altering our attitudes and lifestyles.

But what we can truly take away from the museum is the realization that we have the opportunity to learn about our surroundings: to understand the local flora and fauna, and the historical dimensions surrounding them. This knowledge empowers us to shape our own world and contribute to creating a more livable future. There is no universal recipe for peaceful coexistence with the environment, but by listening, observing, and understanding the signals the natural world conveys – while also recognizing and questioning our culturally constructed realities – we can begin to change both theoretically and practically.

[1]To grasp the fictional nature of the Kamenawai tribe, one must engage more deeply with the installation, as this detail is not explicitly stated in the exhibition text. The work invites interpretation, blurring the lines between myth and reality, urging viewers to question their own perceptions of cultural narratives and ecological futures. More about Bálint Szabó’s work can be found here:https://gosheven.net/KAMENAWAI

[2] Hortobágy is a vast steppe region in Eastern Hungary, known for its unique alkaline grasslands, traditional pastoral culture, and status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is located close to Debrecen.

[3] Aloi, G., & Marder, M. (2021). Getting Entwined: A Foray into Philosophy’s and Art’s Affair with Plants. e-flux. https://www.e-flux.com/notes/552884/getting-entwined-a-foray-into-philosophy-s-and-art-s-affair-with-plants

Artists: CENTRALA – Małgorzata Kuciewicz & Simone De Iacobis (PL/IT), Daniel Godinez Nivón (MX/NL), Illés Zsófia Szonja (HU), Kortmann-Járay Katalin & Mendreczky Karina (HU), Kuzma Eszter Júlia (HU), Gaja Mežnarić Osole & Krater Collective (SI), Thea Lazăr (RO), Szabó Bálint (HU), Szabó Nóra (HU), Vékony Dorottya (HU)

Curated by: (Artistic Directors) Horányi Attila, Süli-Zakar Szabolcs, Török Krisztián Gábor, Vékony Dorottya

Exhibition Title: Learning from Nature? – Botany

Venue: MODEM Center for Modern and Contemporary Art

Place (Country/Location): Debrecen, Hungary

Dates: 07.12.2024 – 23.03.2025

Photos: Dávid Biró