Zuzanna Bober

Aleksandra Kaim (b. 1999) is a young Polish artist whose works critically examine certain aspects of American culture. Her fascination with the US began in childhood, initially through pop culture: films and music. As she matured – both personally and artistically – her once idealistic view of the country began to shift. During her travels across the United States, she encountered a land full of contrasts – wild, brutal, and uncompromising. A place where individuals must be strong to survive, where a system rooted in competition often suppresses empathy. In her screen prints, the country even becomes a synonym for capitalism itself. Kaim continues to be captivated by American culture and its advanced stage of the modern capitalist system, drawing from it and engaging in artistic dialogue with such points. By addressing issues tied to the social struggles in the US – such as in her recent works on the opioid epidemic – she creates a space to reflect on Poland’s own situation as a country that has only relatively recently joined the capitalist world.

To some, this may seem surprising or unconventional – especially to those unfamiliar with the complexities of Polish culture. Poland, part of the Soviet Bloc until 1989, entered the modern capitalist world relatively late, without experiencing phenomena such as the sexual revolution of the 1960s or the secularization of state institutions. Following the dissolution of the Polish People’s Republic (Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa), the country underwent a systemic transformation marked by a series of economic reforms aimed at integrating Poland into the free-market world. This shift affected not only the economic landscape but also Polish culture. A sudden hunger emerged for films, music, posters, and everything associated with American pop culture. The journalist and anthropologist Olga Drenda has described this structure of everyday visual life in post-communist Poland in her book Polish Hauntology: Things and People in the Years of Transition (2018).

For many Poles, the notion of the “American dream” was a deeply personal aspiration. My mother, born in 1975, once told me that her biggest teenage dream was to own a pair of Levis. At the time they cost between $11 and $18 in Poland, and despite his respectable career as an engineer, this was the equivalent of one third of my grandfather’s monthly salary. Those jeans weren’t just a fashion statement, they represented freedom and a sense of individuality, both strongly associated with the United States. Kaim turns this dream on its head. By critiquing the American dream she is in fact challenging its Polish version – a dream of capitalist salvation that for many, like their American counterparts, has turned out to be an illusion.

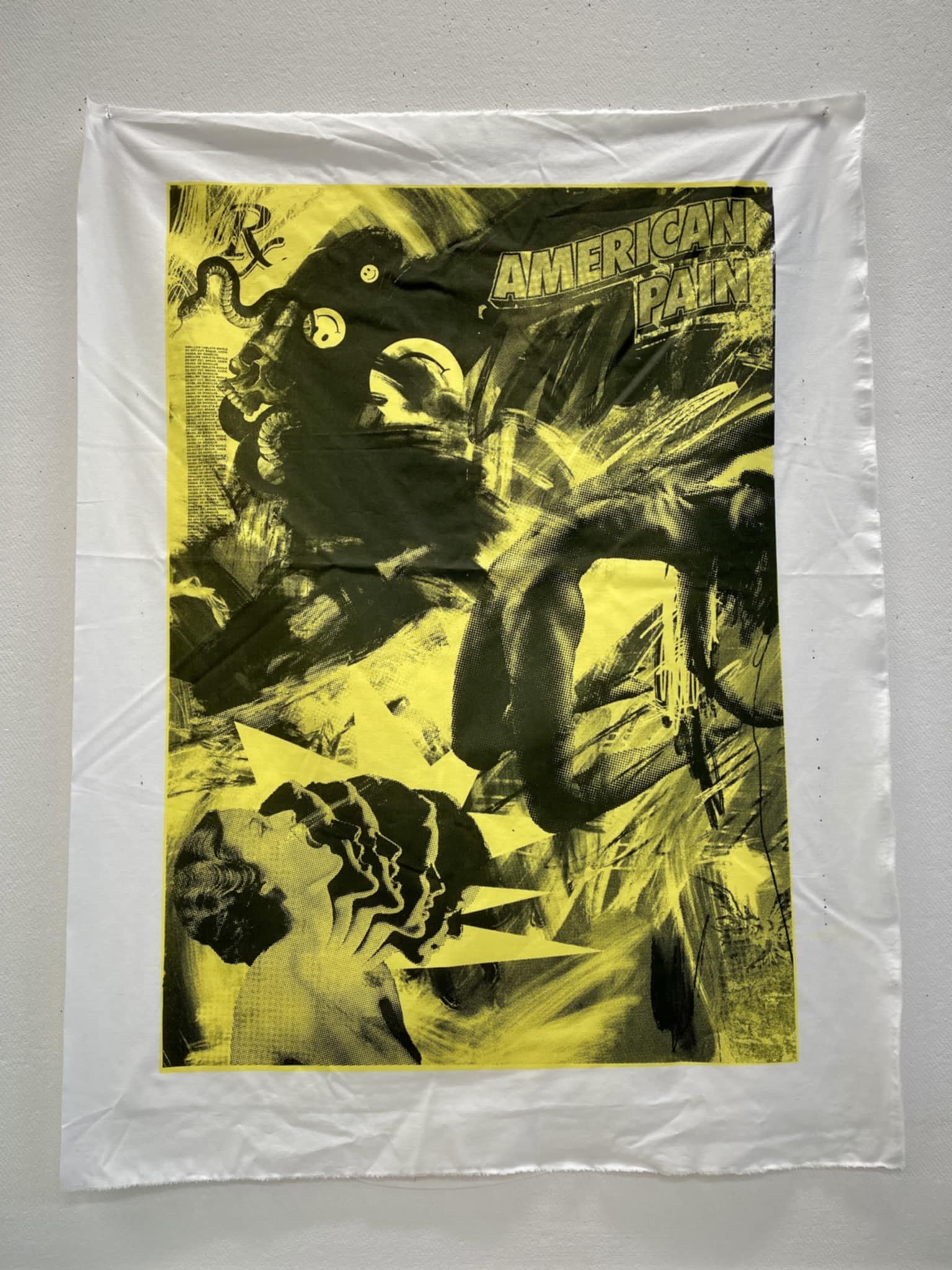

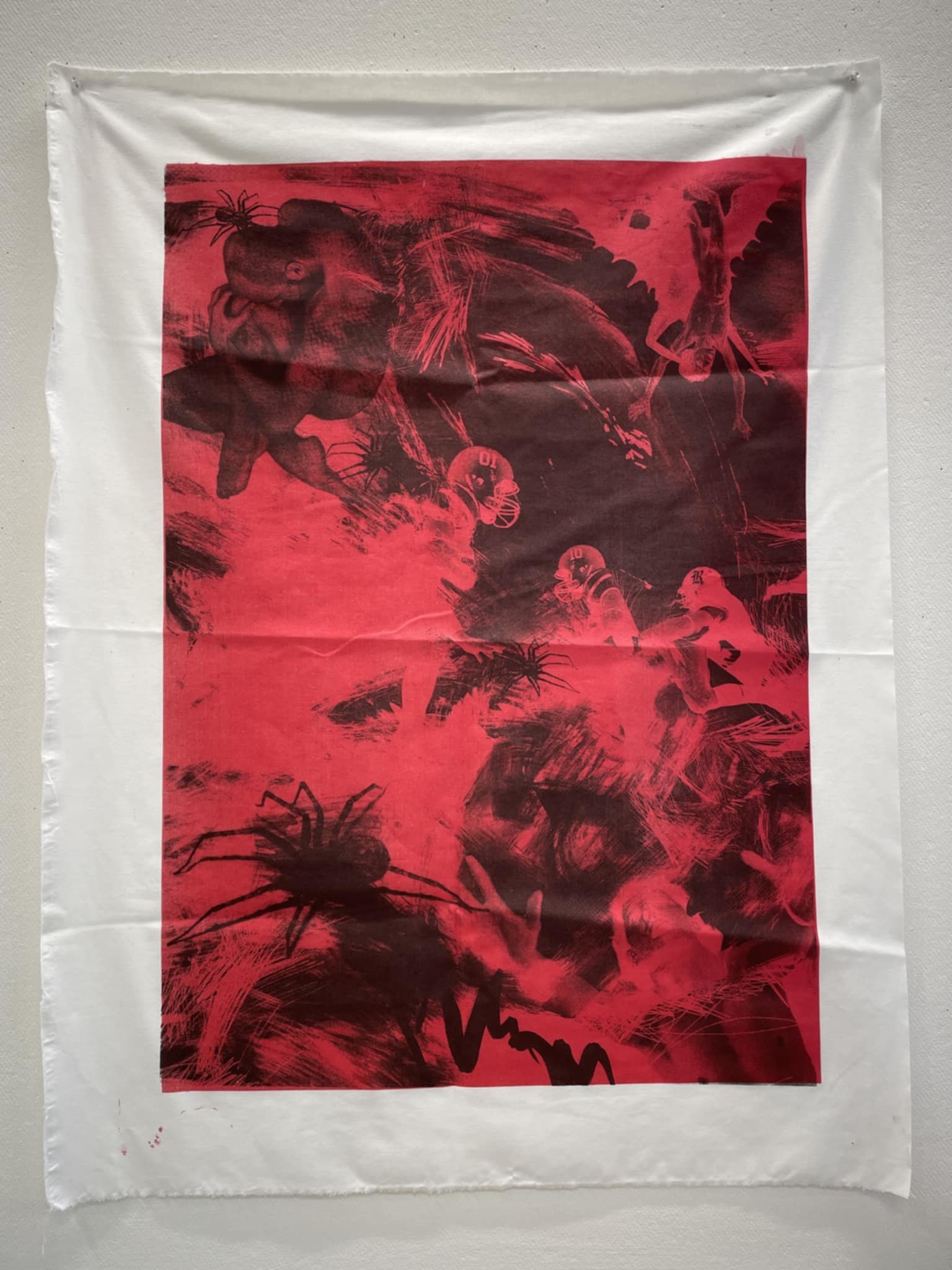

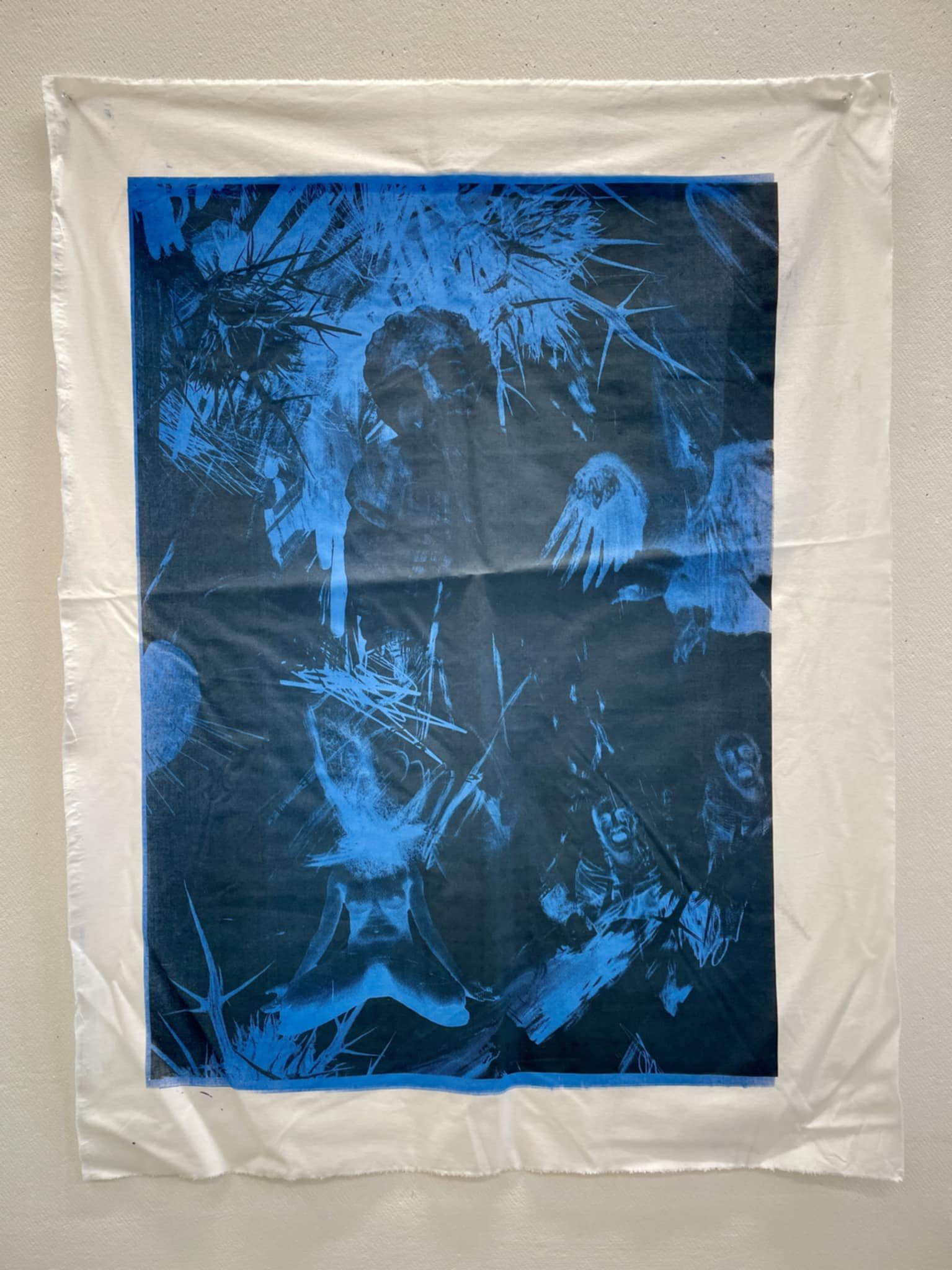

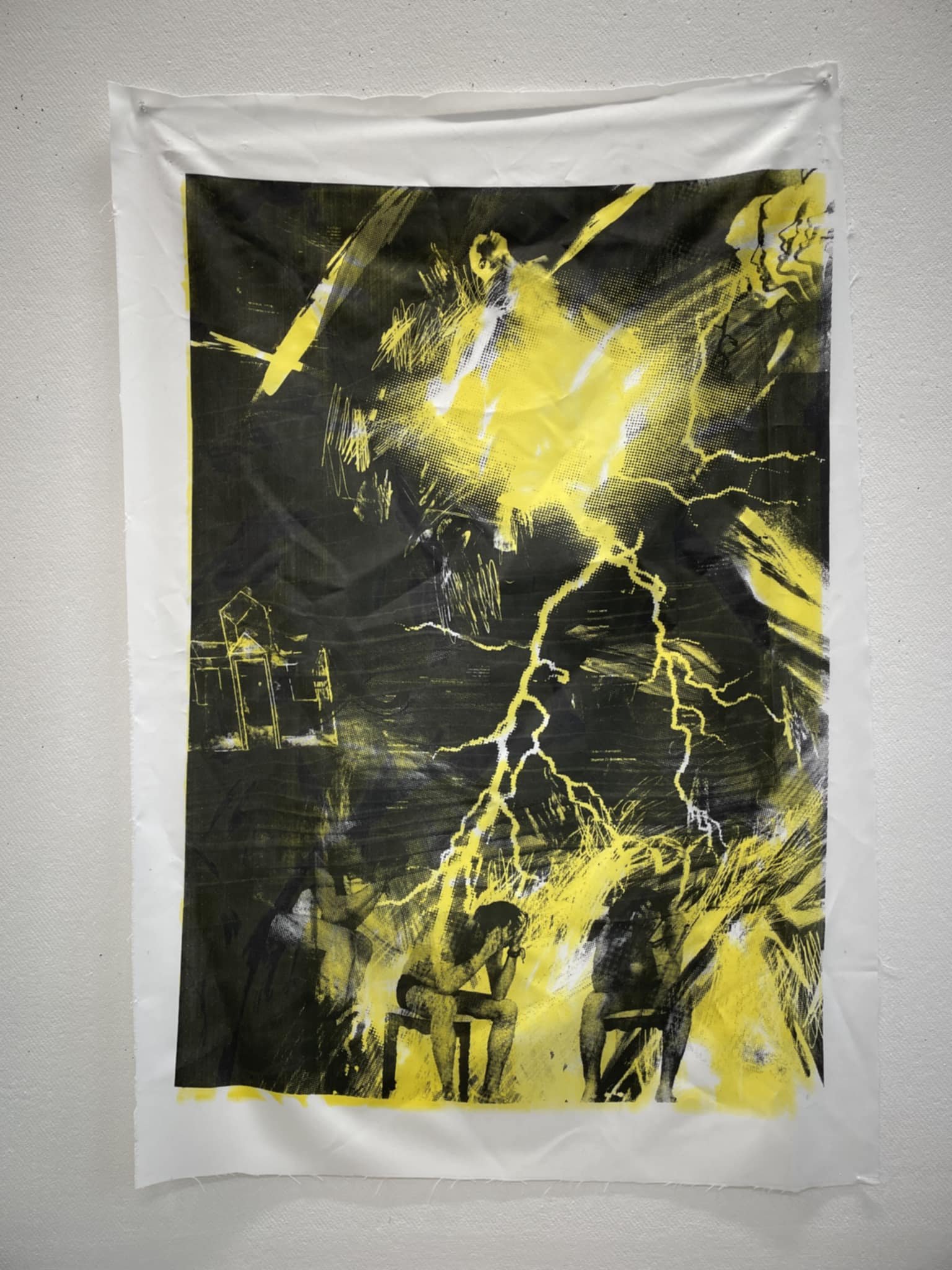

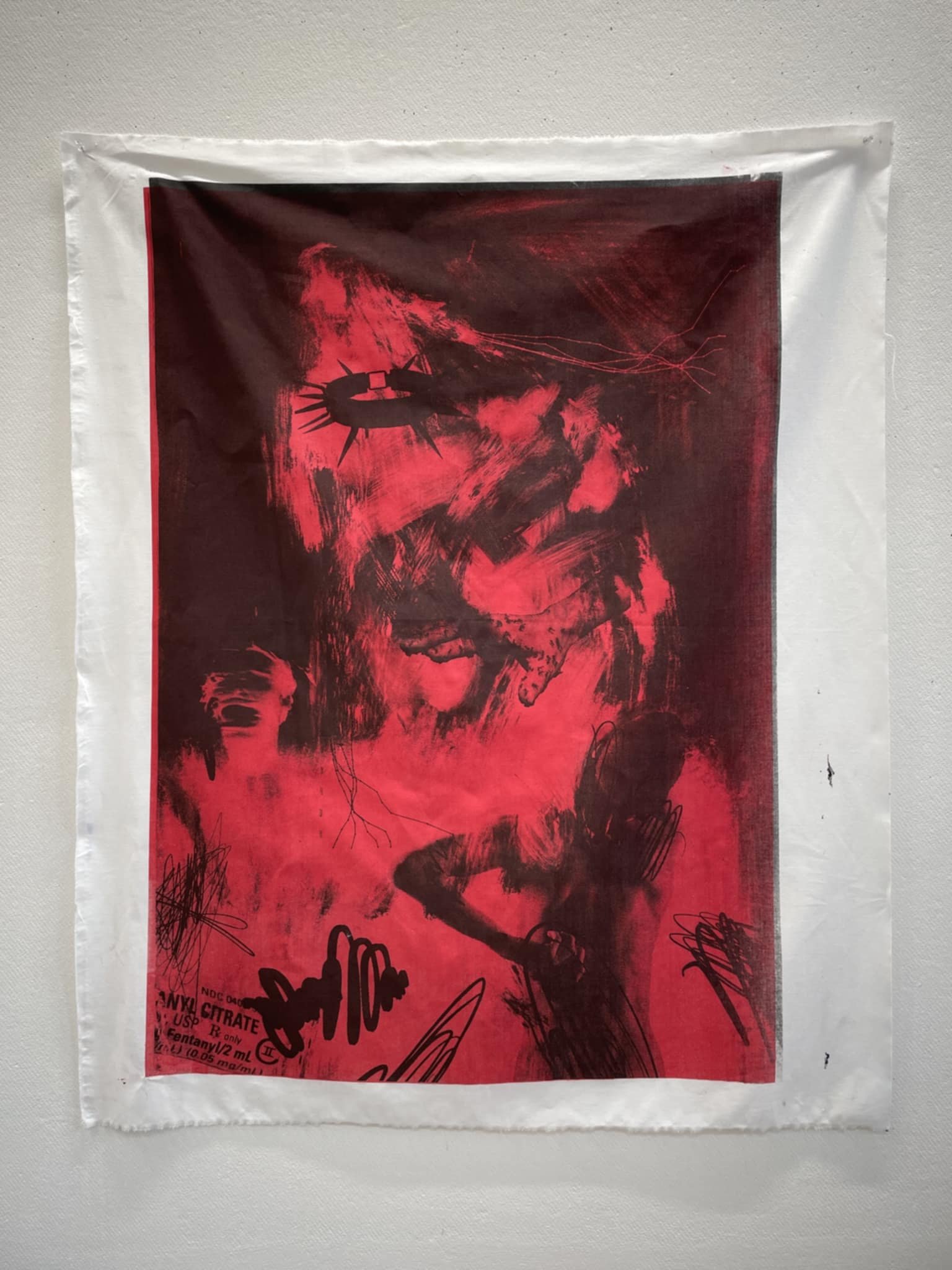

Pain(killer) is a series of screen prints that serve both as a direct commentary on the opioid crisis that began unfolding in the United States in the 1990s, and as a broader reflection on the contemporary world. The US has come to symbolize the contemporary capitalist world – one where illnesses are not only tools in the operations of state biopolitics but also objects of aggressive marketing, leading to the commodification of patients and the privatization of public healthcare systems. From a Polish perspective, this is not a remote issue but an urgent public concern, as the far-right political party Konfederacja is becoming increasingly influential. One of Konfederacja’s most widely discussed demands is the privatization of the Polish healthcare system. In this light, Kaim’s work not only critiques American capitalism – it interrogates Poland’s own uneasy relationship with it.

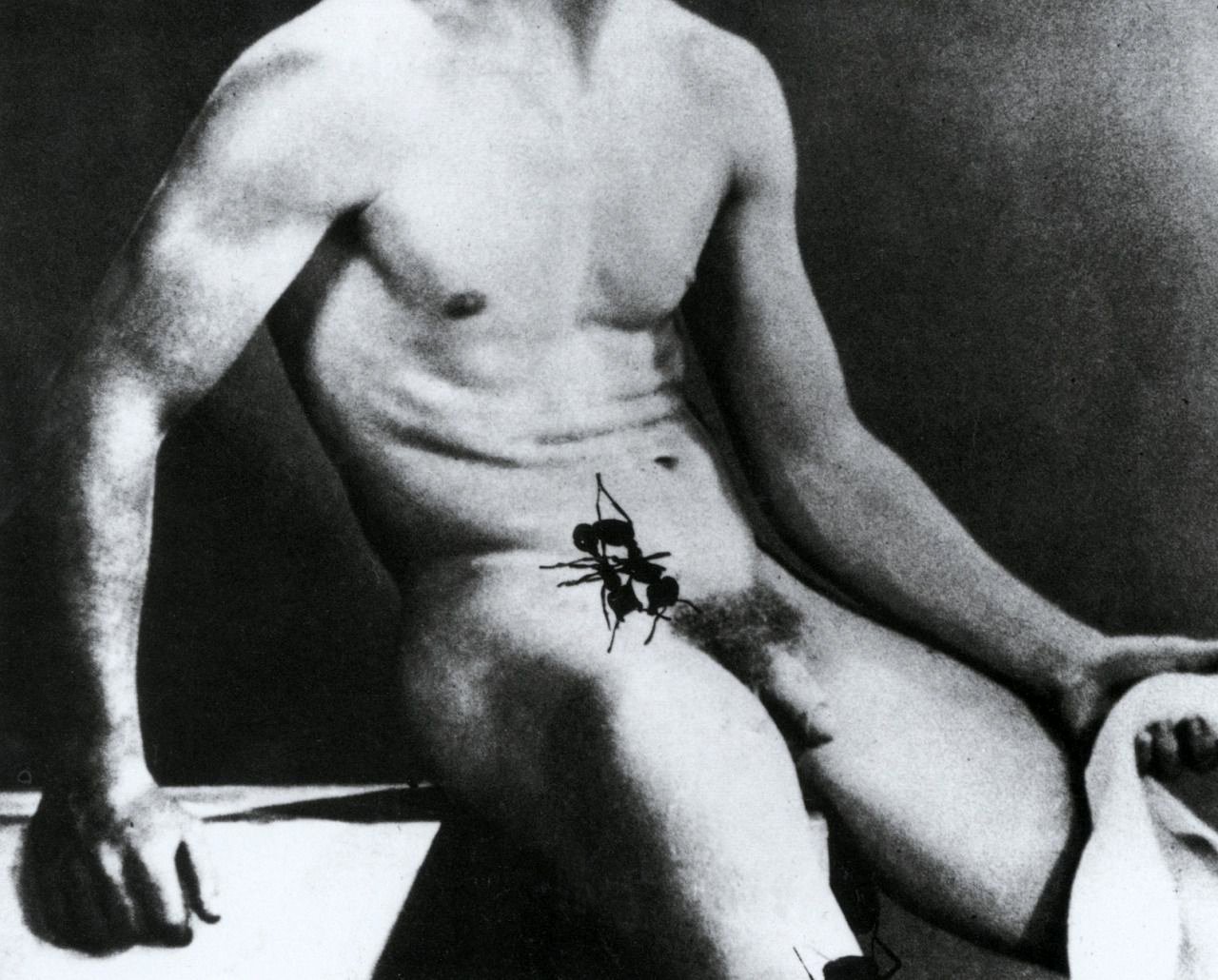

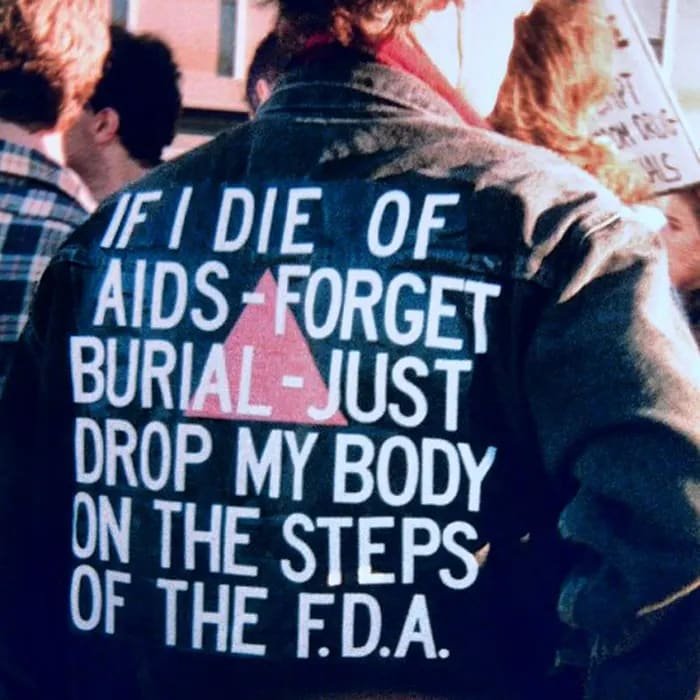

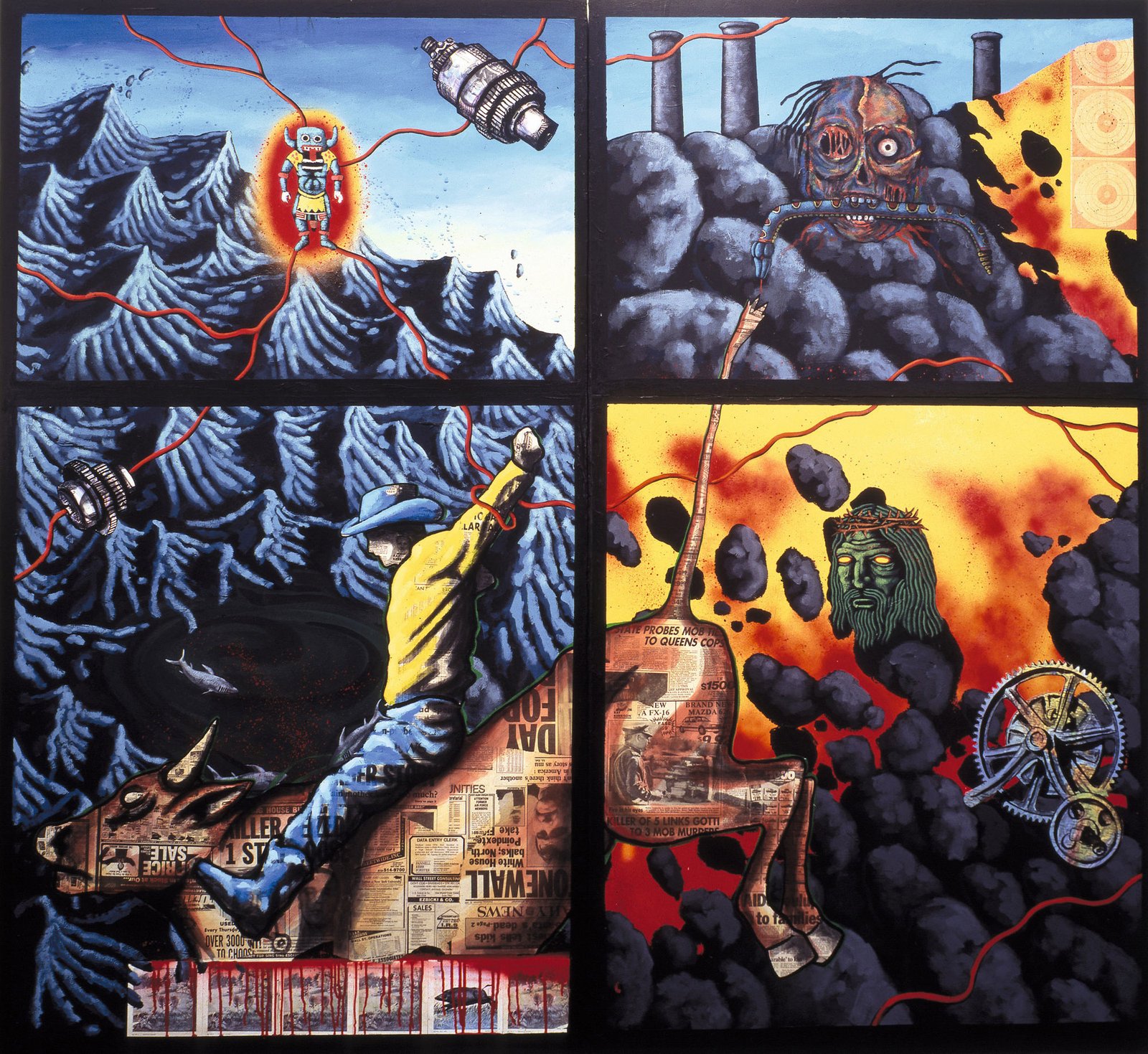

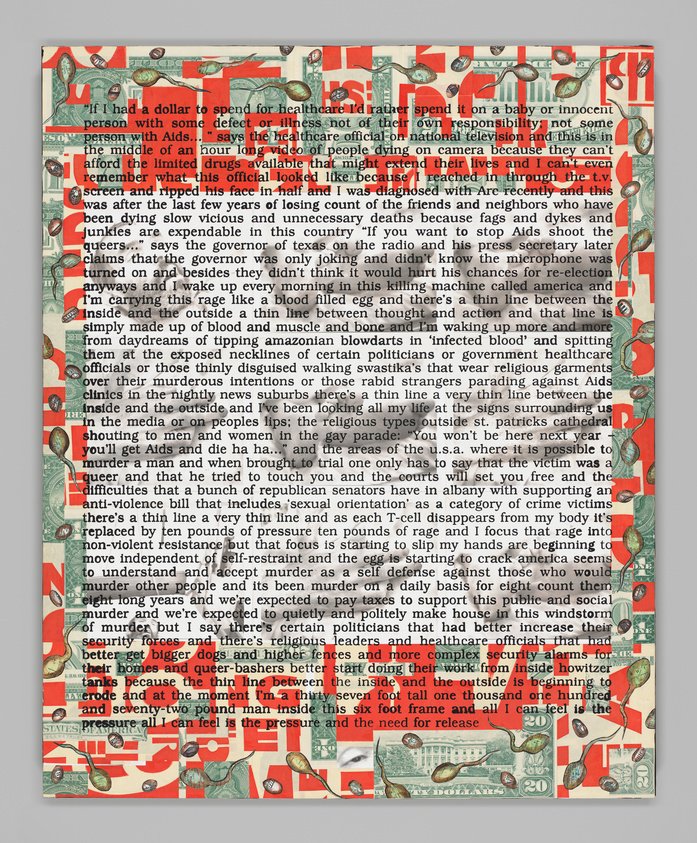

Kaim’s works reveal strong visual parallels with the politically engaged and openly anti-American art of David Wojnarowicz (1954 – 1992). Both artists’ creations possess a quality that is at once vulgar and ritualistic – unveiling the brutal realities concealed beneath right-wing populist discourse, which often takes on a tribal character, calling for the exclusion of those deemed weak or unable to adapt to capitalist reality from the social framework of empathy. During the AIDS epidemic and the Reagan and Bush Senior eras, David Wojnarowicz published Close to the Knives: A Memoir of Disintegration – a collection of creative essays that complemented his visual practice. Wojnarowicz himself died of AIDS at a very young age. He once wrote: “I wake up every morning in this killing machine called America.” Through his artistic work, he became a pioneer of manifesting pain and anger in public spaces, transforming personal suffering into political force. Through his writing, he inspired activists affected by AIDS to transform their anger, suffering, and grief into a political force:

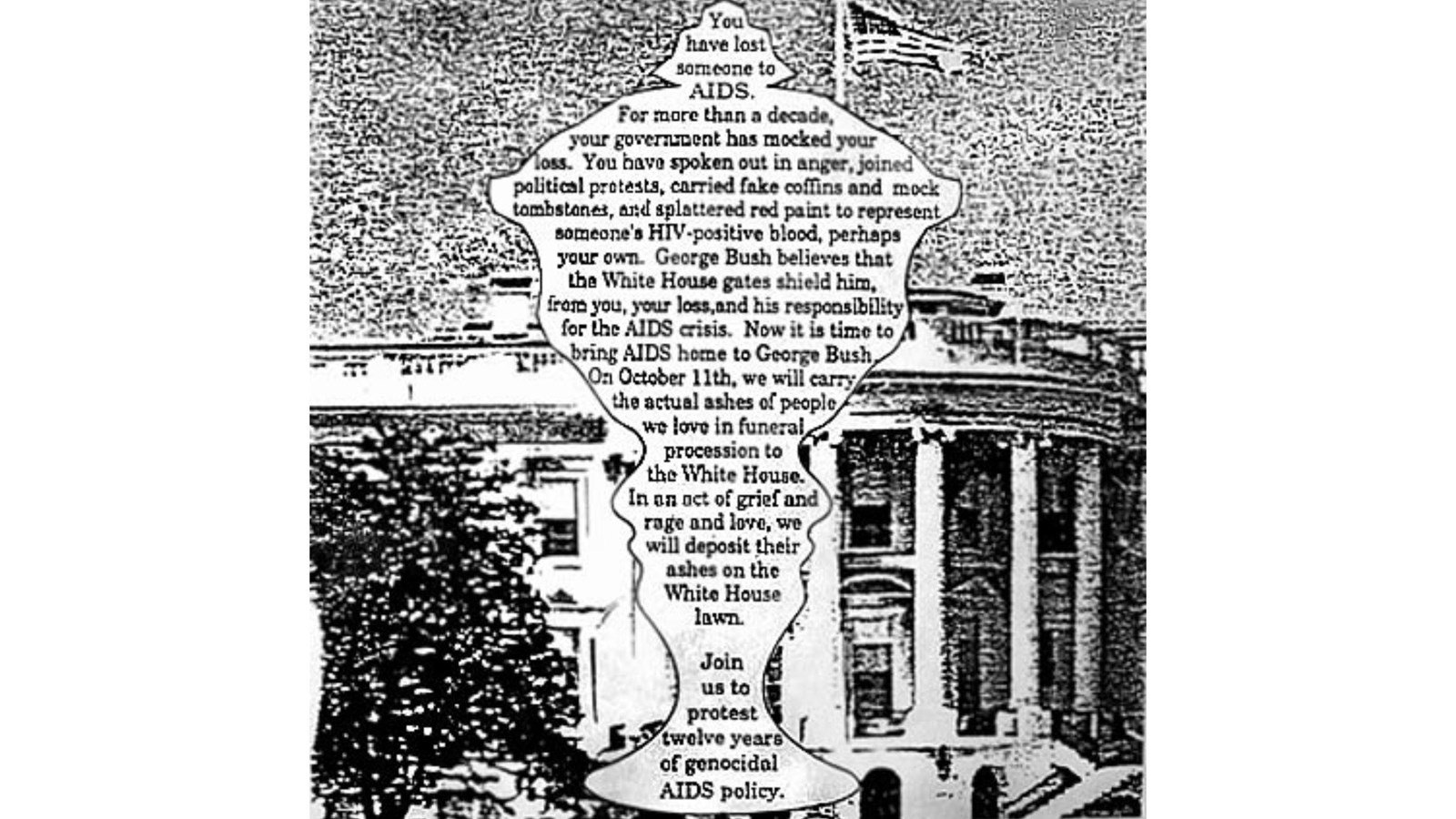

I imagine what it would be like if friends had a demonstration each time a lover or friend or stranger died of AIDS. I imagine what it would be like if, each time a lover, friend or stranger died of this disease, their friends, lovers or neighbors would take their dead body and drive it in a car a hundred miles to Washington DC and blast though the gates of the White House and come to a screeching halt before the entrance and them dump their lifeless forms on the front steps. It would be comforting to see those friends, neighbors, lovers and strangers mark time and place and history in such a public way.[1]

Shortly after Wojnarowicz’s death, his partner Tom Rauffenbart scattered the artist’s ashes in front of the White House. This act was one of the first Ashes Actions[2] – a series of political funerals organized by ACT UP[3] – in an effort to hold the government and the FDA (Food and Drug Administration) accountable for the deaths caused by governmental neglect. ACT UP worked with the public anger, grief, and frustration at the denial of human dignity to people living with AIDS. The organization continues its activism today, applying many of the strategies developed in the 1980s and 90s to oppose American support for Israel’s military actions and to advocate for the inherent human dignity of suffering Palestinians.

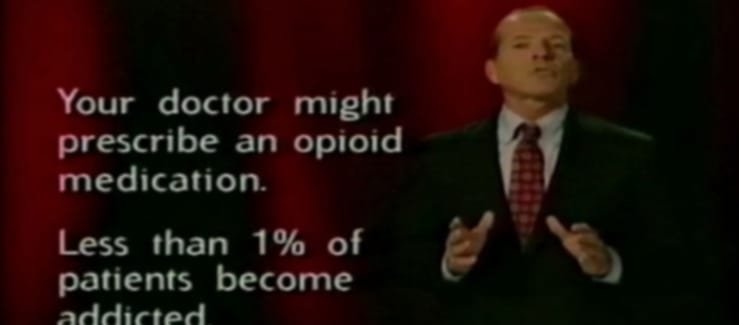

The FDA is a US government agency that, during the AIDS epidemic, denied many people access to the only available treatments. Later, during the opioid crisis – a topic central to Kaim’s work – the same institution allowed pharmaceutical companies to aggressively market opioids for profit, contributing to another public health disaster. The so-called opioid crisis has clearly shown how depoliticizing human suffering in a supposedly apolitical reality ultimately reduces the patient to a passive subject in the hands of pharmaceutical giants. In 1984, the FDA approved the launch of oxycodone. Although oxycodone is twice as potent as morphine, the public was largely unfamiliar with it, which allowed pharmaceutical companies to implement well-planned marketing strategies with little resistance. Even doctors themselves often didn’t fully understand how the drug worked, yet they were encouraged and rewarded by Purdue Pharma to prescribe it, which resulted in the crisis we find ourselves in today.[4]

The colors used in Kaim’s screenprints directly reference the colors of oxycodone tablets – blue for 15 mg, yellow for 40 mg, red for 60 mg, and green for 80 mg. The manufacturer of oxycodone, Purdue Pharma, likely did not choose these colors by accident; they were intended to evoke a sense of harmlessness, resembling colorful candy. However, in Kaim’s works, these colors are transformed into colors of war – raw, distilled, and as aggressive as the marketing campaigns that ultimately ensnared human suffering within the net of their ruthless market mechanisms.

For the vast majority of Americans, taking medical leave involves stepping away from work and losing both a steady source of income and their access to health insurance. In the mid-1990s, the shortcomings of the healthcare system led to a departure from interdisciplinary pain treatment in favor of pharmaceutical solutions.[5] OxyContin was frequently prescribed to manual laborers engaged in physically demanding jobs who were experiencing chronic pain. Their illnesses were often a direct result of their labor – it was capitalism that made them sick and then powerful pharmaceutical companies like Purdue Pharma profited from it by selling them the cure.

Since 1999, 450,000 American deaths have been linked to the opioid crisis. A significant number of these overdoses were connected to products manufactured by Purdue Pharma, as well as to illicit opioids circulating on the black market.[6] Today, Poland is among the top nations globally when it comes to overusing painkillers. Poland is also the only country in Europe where more money is spent on drug advertisements than on ads for other service sectors. In 2024, €738 million (PLN 3.26 billion) was spent on pharmaceutical advertising in Poland. This represents a 14% increase in the sector’s budget compared to the previous year. The most heavily promoted products were the over-the-counter painkillers Apap and Ibuprom.[7] For comparison, in the same year, the Polish National Health Fund (NFZ) received a state subsidy of €1.93 billion (PLN 8.7 billion).[8] This means that spending on pharmaceutical advertisements amounted to the equivalent of more than one-third of the NFZ’s annual budget.

In a world where human suffering is entangled with market mechanisms due to the privatization of the pharmaceutical industry, Kaim’s Pain(killer) deconstructs the deeply ingrained stereotype of the addicted individual as weak-willed and indolent. It exposes the mechanisms of social control that renders the suffering person “guilty” of their own pain – undeserving of compassion and subjected to social disdain. The crisis currently facing social institutions – and the uncertainty surrounding the foundations on which their functioning is based – finds a superficial solution in offering affected individuals self-help techniques. If they fail to apply these techniques effectively, they are then held responsible for their own fate. An individual may take painkillers instead of seeking comprehensive treatment because they might not have access or funds. They may go to therapy (if they have access to it) in order to change their perspective rather than even considering instead, changing the circumstances that causes them the physical and psychological pain to begin with. Additionally, the omnipresent lifestyle content on social media promoting healthy living, eternal youth, and beauty attainable through the constant purchasing of new and ever-evolving products, shifts responsibility onto the individual. One is expected to know how to invest in oneself, in one’s health and well-being, which becomes yet another form of capital to be accumulated. This distorts the sense of self as part of something greater and contributes to the erosion of social responsibility and the idea of political community.

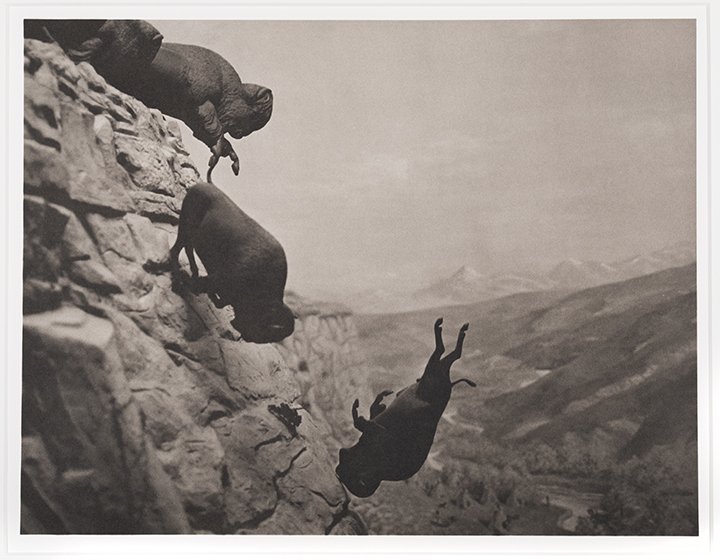

The deeply rooted image of the “addict” in Polish culture emerged during the country’s political and economic transformation (post 1989) and was primarily associated with alcoholism. This visualization of addiction was strongly tied to the notion of having failed to take advantage of the opportunity that capitalism was supposed to represent. Polish scholar Katarzyna Warmuz has described how liberal elites benefited from reinforcing the representation of people struggling with alcoholism as individuals lacking willpower, almost animalistic in nature. These people were portrayed as incapable of rational thinking and thus were failures at adhering to the liberal ideals of a free market society because they were driven instead by primal, wild urges.

Capitalism, understood in its broadest sense, feeds not only on material resources but also on psychological ones. The middle class, immersed in a market loyalty ethos, inevitably finds itself in a double bind, condemned to constant anxiety and a sense of helplessness. On the one hand, they are pressured to maintain a constant state of betterment, expressed, for instance, through the encouragement to take out loans even in highly unfavorable economic conditions. On the other hand, they are burdened with a persistent sense of guilt for the very economic difficulties they are subjected to. People are made to believe that they are the sole architects of their destiny and that they can always “pull themselves up by their bootstraps” and work harder, save more, and spend less on minor pleasures.

During Poland’s transition into capitalism, society was kept in a state of diffuse panic. Individuals were forced to reconcile the contradiction between depressive living conditions and the newly imposed free-market optimism – an optimism that demanded constant self-improvement, privatized public services, and perpetuated the illusion that anyone could become a wealthy entrepreneur. The figures in Kaim’s images experience both agony and euphoria simultaneously, thus both conforming to and escaping the logic of the free-market paradigm. Their suffering is not only physical but also deeply spiritual. By giving them the aspect of spiritual pain, Kaim returns to them a soul – something that allows them to become more than passive subjects in the heartless manipulations of the state and capital. In reality, every solution offered to the middle class merely deepens the double bind they are trapped in. Radical psychotherapist David Smail noted that even seemingly more holistic approaches to suffering, such as psychotherapy, in fact play a key role in the depoliticization of pain. In the cruel words of Margaret Thatcher, “There’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families, and no government can do anything except through people, and people must look to themselves first.” Smail hears this in the echo of almost every modern therapeutic approach. These approaches focus on early life experiences and are coupled with self-help methods that ultimately place full responsibility on the individual for their own fate. The result is that the individual becomes solely accountable for their health, wellbeing, and destiny in a world that causes them pain.

The works of Kaim and Wojnarowicz both construct a narrative around the urgency of addressing the social dimensions of fear and anger inspired by governmental failures, whose public expression is increasingly constrained in our supposedly depoliticized reality. In a world where human suffering is entangled in market mechanisms and where the pharmaceutical industry continues to capitalize on illness, art becomes a call to acknowledge pain and to reclaim public anger as a force for political resistance, constituting direct reaction when governments are failing their people time and time again.

The suffering of any human being is an existential fact and should not merely serve as a metaphor for the collapse of social systems. In Kaim’s (PAIN)KILLER, numerous creatures such as snakes, spiders, and ants, or animal fangs and devil heads appear as the embodiments of unspoken suffering, for which there is no place in the world of high capitalism. To paraphrase Mark Fisher, the privatization of human suffering is an integral aspect of the capitalist project, which seeks to erode the very concept of society, thereby destabilizing the foundations of mental well-being.[9] The figures depicted in Kaim’s screenprints, trapped in the vicious cycle of addiction and capitalism, simultaneously inhabit both private and political spheres. Their bodies exist in a paradox of agency and passivity, experiencing ecstasy through suffering, with pain manifesting on both physical and spiritual levels. To manifest anger in public space must be nowadays, according to Fisher, a profound political project.

The art of anger, as exemplified by Kaim’s and Wojnarowicz’s visual practices, holds the potential to shape collective bodies by working with frustration and resisting indifference in the face of injustice caused by Western societies’ lack of empathy and weakening sense of social belonging. As Fisher observed, we are in urgent need of an explosion of public anger – one that could lead to the reconstruction of the public sphere and contribute to the healing of many of capitalism’s pathologies. According to the author of Capitalist Realism, the democratisation of the public sphere has never truly occurred. Reimagining a public space shaped by collective frustration and the transformative power of anger may enable the emergence of new forms of social care and a revitalised sense of community.

Kaim’s series Pain(killer) (2024) received a special distinction from the Art React Foundation as part of the Grand Prix Grafiki competition. In September 2025, the series will represent Poland at the International Biennale of Graphic Art in Armenia. Pain(killer), and Kaim’s earlier work, The (Not)United States, have been exhibited at the International Graphic Art Triennale in Kraków.

Sources

ACT UP New York. (n.d.). Ashes action. Retrieved May 30, 2025, from https://actupny.org/diva/synAshes.html

Detrano, J. (2016). The Four-Sentence Letter Behind the Rise of Oxycontin. Center of Alcohol & Substance Use Studies, Rutgers University. https://alcoholstudies.rutgers.edu/the-four-sentence-letter-behind-the-rise-of-oxycontin/

Drenda, O. (2016). Duchologia polska: Rzeczy i ludzie w latach transformacji. Karakter.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Drug overdose deaths. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved May 30, 2025, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/drug-overdoses.htm

Fisher, M. (2014). The privatisation of stress. In k-punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings of Mark Fisher (2004–2016) (Eds. D. Ambrose & M. Fisher, 2018). Repeater Books.

Krakowska, J. (2021). Odmieńcza rewolucja (pp. 38-59, “Gniew Davida Wojnarowicza”). Wydawnictwo Karakter

Ministerstwo Finansów. (2025). Ministerstwo Finansów – Strona główna. https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/

Quinones, S. (2015), Dreamland: The true tale of America’s opiate epidemic. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Warmuz, K. (2022). Wyjące, pijane potwory – o wizerunku osób uzależnionych po transformacji. Praktyka Teoretyczna, (44/2022). https://doi.org/10.14746/prt2022.4.6

WirtualneMedia.pl. (2024, 10 stycznia). 14 proc. więcej na reklamy farmaceutyków. Dominują Aflofarm i USP, najmocniej promowane Apap i Ibuprom (analiza). https://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/artykul/14-proc-wiecej-na-reklamy-farmaceutykow-dominuja-aflofarm-i-usp-najmocniej-promowane-apap-i-ibuprom-analiza

Wojnarowicz, D. (1989). Post Cards from America: X-Rays from Hell. In Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing (s. 6). Artists Space. https://artistsspace.org/media/pages/exhibitions/witnesses-against-our-vanishing-3/554200648-1623172996/wojnarowicz_postcards.pdf

Sturis, D. (2018, 19 listopada). Lek przeciwbólowy OxyContin uzależnił i zabił już tysiące ludzi w USA. W Polsce jego producent wspiera akcję “Szpital bez bólu”. Duży Format. https://wyborcza.pl/duzyformat/7,127290,24171737,lek-przeciwbolowy-oxycontin-uzaleznil-i-zabil-juz-tysiace.html

Świrem, K. (2022). Klasa średnia i „choroba braku granic”. Praktyka Teoretyczna, (44/2022). https://doi.org/10.14746/prt2022.4.3

[1] David Wojnarowicz, „Postcards from America: X-Rays from Hell”, w: Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, Artists Space, Nowy Jork 1989, s. 6. Dostęp online: https://artistsspace.org/media/pages/exhibitions/witnesses-against-our-vanishing-3/554200648-1623172996/wojnarowicz_postcards.pdf.

[2] See also Joanna Krakowska, Odmieńcza rewolucja. Performans na cudzej ziemi, subchapter “Gniew Davida Wojnarowicza”, pp. 38-59

[3] Ashes Action,” ACT UP New York, accessed May 30, 2025, https://actupny.org/diva/synAshes.html.

[4] Quinones, S. (2015). Dreamland: The true tale of America’s opiate epidemic. (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2015), 187-205

[5] See also Quinones, S. (2015). Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2015), 92-98

[6] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug Overdose Deaths. National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/drug-overdoses.htm (accessed May 30, 2025).

[7] WirtualneMedia.pl. (2024, 10 stycznia). 14 proc. więcej na reklamy farmaceutyków. Dominują Aflofarm i USP, najmocniej promowane Apap i Ibuprom (analiza). https://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/artykul/14-proc-wiecej-na-reklamy-farmaceutykow-dominuja-aflofarm-i-usp-najmocniej-promowane-apap-i-ibuprom-analiza

[8] Ministerstwo Finansów, Ministerstwo Finansów – Strona główna, dostęp 2 czerwca 2025, https://www.gov.pl/web/finanse/

[9] Fisher, M. (2011). The privatisation of stress. Soundings: A Journal of Politics and Culture, (48), 123-133.