Janek Owczarek and Piotr Policht in conversation with Ewa Borysiewicz

Ewa Borysiewicz: You curated this year’s edition of the exhibition series organized by Galeria Bielska BWA, which every two years since 2000, focuses exclusively on painting. Before we dive into your exhibition titled Don’t Hate the Player, Hate the Game, I’d like to ask: how do you both personally feel about this medium?

Piotr Policht I must admit that nowadays I tend to lean towards historical positions, while being drawn less to the contemporary ones. In all sincerity, even curating an exhibition consisting solely of painterly works is not representative of what interests me most in contemporary art at the moment. But we witness such an immense overproduction in the visual arts that it’s possible to wring a lot of interesting things out of any medium, so without bending over backwards it is possible to produce an interesting exhibition out of painting, even though there’s an increasing dissatisfaction regarding this particular medium growing inside me.

EB: Where does it come from?

PP: The feeling is not only related to the sheer amount of painting being produced and shown at the moment, the work just seems increasingly clichéd and follows simpler and more illustrative patterns. A word of explanation: Janek and I discussed this phenomenon on the occasion of Józef Chełmoński’s[1] retrospective at the National Museum in Warsaw, which we both enjoyed very much. With historical painting, particularly up until the early 20th century, reproductions – whether in high-quality publications or digital formats – have often failed to do the original work justice. When you encounter an “iconic” piece in a museum for the first time, you notice details that are often lost even in the highest-quality reproductions. This direct connection with the original becomes incredibly significant. In contrast, with recent paintings, it’s common to see a work on platforms like Instagram and think, “Wow, that’s interesting.” But when experienced in person, a contemporary piece can leave you with a sense of disappointment, or a feeling of “flatness,” both in terms of theme and technique.

Janek Owczarek: I wouldn’t say that I dislike painting, but for various reasons, it’s the medium that’s currently in the spotlight, and within it, you can trace much of what hasn’t been particularly interesting about art in recent years. Like Piotr, I find very little in contemporary art that truly moves me or leaves me in awe as much as Giotto, Caravaggio or a stroll through one of the great European museums. With contemporary painting, I increasingly get the sense that I’m looking at remakes, remasters, or returns to older aesthetics. 21st-century painters often echo the Surrealists or early 20th-century Cubists, though infused with progressive concepts and backed by complex personal stories of the artists themselves. Then, painters depicted modernity, capturing the essence of contemporary life. Today, however, painters tend to focus more on their own lives. But a compelling personal story doesn’t always translate into a compelling work of art. When you look at the bigger picture, it feels like the medium is in a state of stasis–and that’s putting it mildly. Though one has to remember that painting, as a medium, is quite specific: it’s inherently conservative, essentially unchanged in its core formula since the 14th or 15th century. Yet, within this space, there seems to be little interest in seeking new forms of expression, new languages, or taking risks.

EB: The works on display at Galeria Bielska BWA are predominantly contemporary, yet in your curatorial concept, you reach far back in history, even to the point of invoking Leon Battista Alberti – whose most famous treatise, “De Pictura”, dates back to 1453 – as a patron of the exhibition. I’m curious about the reasons behind this choice.

JO: The exhibition had a very clear framework from the start: it had to be a painting show. When faced with such a specifically defined task, I like to return to the foundations – in this case, of painting. And for this medium, Alberti is an obvious choice. On the other hand, he may seem an unusual one, as many people find it odd to revisit his writings today. But a close reading of his work shows that Alberti remains highly relevant. His advice to 15th-century painters can easily be applied to today’s artists. For example, Alberti writes about the importance of cultivating a personal brand. He also stresses that, alongside their work, artists are citizens who must consider how they present themselves socially. Next: he emphasized the role of criticism from art experts, while noting the value of feedback from friends and colleagues. Furthermore Alberti was a strong proponent of using new technologies to make one’s artistic career easier. The more we read him, the more we realized that Alberti is, in fact, very contemporary – essentially, he’s the patron saint of painting as we know it today.

EB: Why not opt for a more contemporary reference, like Marcel Duchamp, for example?

PP: To build on what Janek said: perhaps it’s not so much that Alberti is particularly contemporary, but rather that painting today feels somewhat out of date. Duchamp, who is often seen as a founding figure of the avant-garde, didn’t seem necessary in this context. If you look at the state of painting from a global perspective, it almost feels as though certain avant-garde upheavals never took place at all. Contemporary painting can often draw from avant-garde aesthetics and reference certain experimental movements, but it has nothing to do with an avant-garde approach: it doesn’t strive to push any boundaries.

EB: The theme of stagnation in painting keeps resurfacing in our conversation. Since the “the game” in the title of your exhibition refers to the market, and the core subject of your show revolves around transgressive strategies toward the – often toxic and exploitative – bond between art and capitalism, I was wondering if you see the commercialization of painting as the source of this lethargy?

JO: First of all, I wouldn’t single out painting alone – I’d say it’s part of a broader cultural trend. When it comes to visual arts, painting just happens to be the most visible medium right now: it’s prominently featured in private galleries, institutions, and fairs, so it’s really a matter of statistics. But when it comes to this kind of creative stagnation – remaking classics, revisiting the past, resurrecting forgotten artists, rehashing old brands – this is a wider cultural phenomenon. Just look at the film, fashion, music, or video game industries.

PP: As to whether the market is the cause, that would certainly be a very simplistic thesis. We also don’t want to completely demonise and draw such a black and white picture. Capitalism is probably the main, but certainly not the only factor. The current state of affairs is also a matter of art education and cultural and social factors.

EB: Does this tendency to look backward rather than forward indicate a lack of faith in the social agency or influencing reality outside of the medium itself – or art in general?

PP: Personally, I’ve never believed in the idea of art having a direct impact on reality, and it seems to me that it has never really existed. Seriously, is there any historical moment where we can prove that art truly influenced reality? Sure, you can argue that art has been used as effective propaganda for specific courts or religions. But take Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, for example: she painted a stunning portrait of Marie Antoinette as a loving mother to counteract her negative public image. Yet, that didn’t save the queen from the guillotine. The idea of art having social agency is a myth perpetuated by the avant-garde. To expect painting – or the visual arts more broadly, both being niche sectors of culture – to have any significant social impact seems naïve to me.

JO: I agree. When we think of art in terms of political banners or iconography tied to political statements, we tend to miss the broader, subtler ways art can be causal and political. The ideas in David Joselit’s “Art’s Properties” resonate with me: art can be used, and has often been used, for example by rulers throughout history. Its very nature makes it politically open to interpretation. However, I think its power is often overestimated when it’s seen as a tool for direct political influence. Take Napoleon, for instance: he used art, but only because he stole it and presented it as a symbol of his own power. Antique sculptures or an Egyptian sarcophagus aren’t inherently political works, but their appropriation and display turned them into powerful political tools. Similarly, the same property of art was exploited by the French Revolution, the Musée des Monuments Français – which showcased art objects taken by the revolution from the courts and churches – being a case in point. This too was a political use of art: by bringing it into public museums and displaying it in chronological and stylistic manner, it was given a new social function, for citizens to engage with as part of a newly forged national identity.

EB: So, what do you look for in art?

JO: In art I look for that feeling which is hard to describe, something close to awe mixed with that famous je ne sais quoi. It can manifest in very different, sometimes contradictory ways. For example, when I look at “GDFJKGHUIERHTRHI” by Tymek Borowski, which is featured in our show, I feel both melancholy and exhilaration at the same time. It’s one of the best sensations I can think of: you don’t know exactly what it is, but it makes you wonder where it comes from and why you feel that way. It’s like someone is speaking to me in a language I don’t understand, but still managing to affect me. Another artist in the show, Patrycja Cichosz, has mastered the ability to make the viewer feel uneasy. Same goes for Zuzanna Bartoszek’s “Mercedes 170 V”: the car, favored by the Nazis, is depicted at the center, its headlights glaring straight at you as if trying to blind you while the machine’s body shines eerily.

And this applies to all the works on display at Galeria Bielska: they are, first and foremost, exceptional paintings, exceptional works of art. While the context of the market is important for the exhibition, we consider each of these works to be great by their own merit and did not select them as mere illustrations of a curatorial thesis.

PP: What Janek said is crucial because, contrary to what we said earlier, we’re not blasé or discouraged. This exhibition is made up only of works that truly move us. The uncertainty Janek refers to is an important criterion in itself. In the face of this flattening I was mentioning, where painting can sometimes feel like a mere signifier, that sense of uncertainty becomes very valuable. It’s that moment when you look at a painting and you’re not quite sure what you’re looking at. Even if the visual motif is clear, the meaning of it remains ambiguous, and you find yourself wanting to spend more time with it. You get the sense that there’s something beneath the surface. You pay attention to how appealing the piece is as an artifact in itself.

It also felt important to create a show that would treat painting seriously. While painting has dominated the programs of institutions, private galleries, and art fairs in recent years, no one has approached it in a way that questions and situates its role within contemporary art practice. An exhibition like ours was simply lacking.

EB: This is the idea behind the Bielska Jesień curated exhibition series: to explore the state of painting today. The ties between painting and the market stretch back centuries, further than any other art medium, so by binding the works together within this context, you simultaneously root the show in the past while finding commonalities with the present.

JO: The general premise of the exhibition emerged in response to the question of what major issues today shape what painting looks like. From the Renaissance onward, painting was elevated as the only medium in the arts that transcends craftsmanship, becoming – to quote Leonardo – cosa mentale, a thing of the mind, closely linked to the artist’s inner workings and a faithful realization of their conceptual intentions. Early on, this medium – a rectangle on canvas, easy to transport, exchange, sell, and collect – acquired the status of a commodity. Over the centuries, this process of commodifying painting has only accelerated, right up to today’s auction records, which the media love to sensationalize. Notice how no one gets excited about auction records for sculpture, and it’s always painting that serves as a bellwether for the condition of the art market. But the exhibition wasn’t intended as a simplistic critique of the market, private galleries, or artists “selling out” for commercial success. That wasn’t the point. Instead, it aimed to soberly analyze the many different market-art relationships and examine them from various perspectives.

EB: These perspectives unfold across the seven chapters of the exhibition, each highlighting a different facet of the unbalanced and uneasy relationship between art and the market. The chapters explore various angles: the context in which the works were created, the conditions under which the artists operated, their unorthodox strategies towards the market, and the role of painting as a commodity fetish.

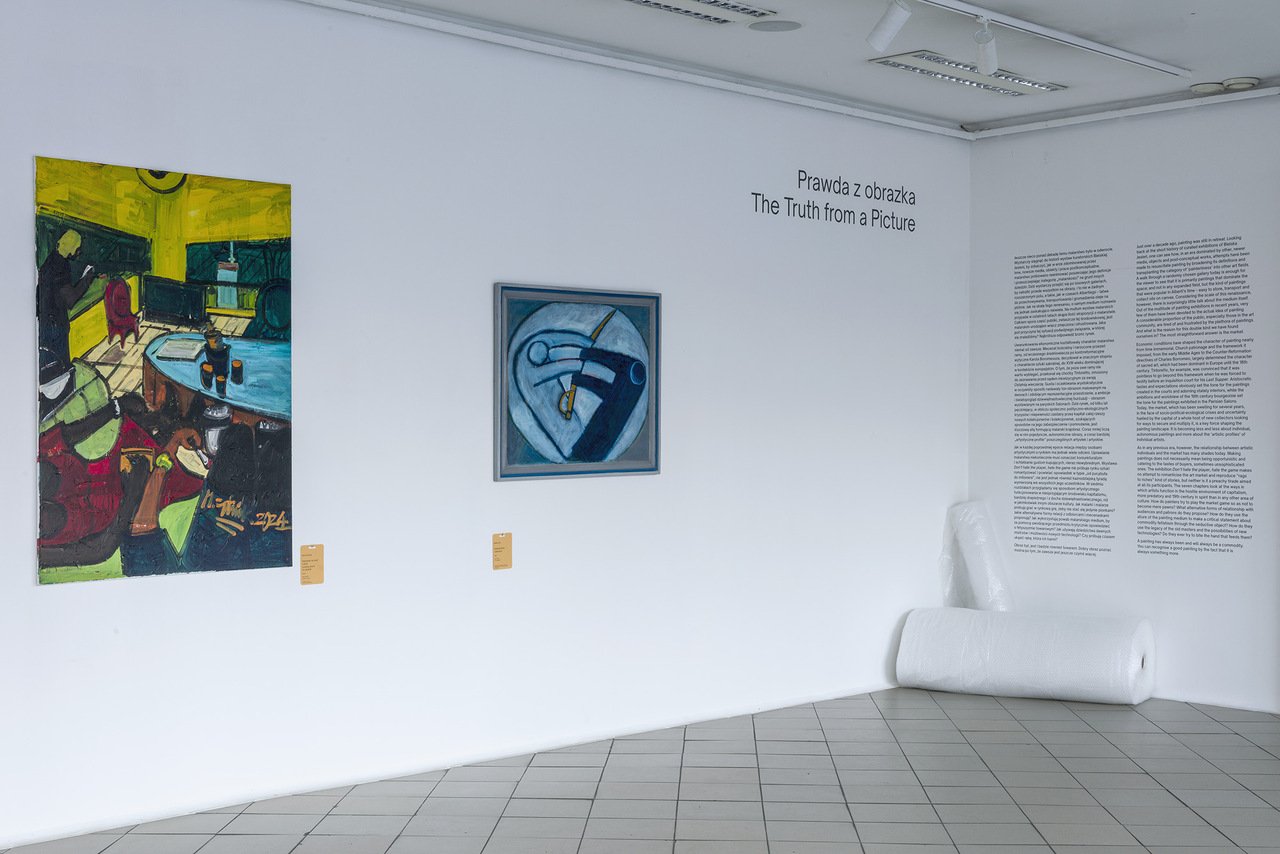

PP: We’re also aware that our perspective is just one of many, and that painting today can be approached from an entirely different viewpoint. For this reason, we didn’t feel the need to be addressing the viewers from an ivory tower. The titles of the subsequent chapters are somewhat tongue-in-cheek, as is the scenography, designed by Kuba Maria Mazurkiewicz: references to art fair architecture, a bubble-wrap chapel housing two works that heavily draw from art history, and supermarket tags instead of wall texts. It also involves presenting paintings the old school way: on easels. This is the case of Tomek Kręcicki, whose works are placed in a kind of dialogue – a duel, if you will – with Józef Kluza, his predecessor from Krakow, who passed away half a century ago. Their works depict literally the same objects, use strikingly similar aesthetics, formats even, but yet created in completely different historical, social, political, and economic contexts. Both can be considered very successful artists: Kluza (although now rather forgotten) in communist, Kręcicki in capitalist Poland. We wanted to show both artists side by side to examine how these contrasting contexts influence the nature of their painting. When you look closely, the differences start to be very visible: a glass in Kluza’s painting and a glass in Kręcicki’s painting are, in effect, two completely different objects.

EB: Kluza, even though he began his career in a context vastly different from the capitalist one, still engaged with market dynamics within that system. Another artist, Marian Kopf, whose Collectors (1966) is on view in the show, caricatures collector figures and addresses the economic struggles of the artist. He doesn’t shy away from blunt commentary, and it’s noteworthy that such direct observations are rarely found in what we might consider mainstream contemporary painting today.

PP: Yes, stories about bizarre conversations with collectors often circulate at informal gatherings, but they rarely find their way into the art itself. It’s interesting that this theme tends to appear in the works of painters who are somewhat on the fringes. Michał Żytniak, for example, is more known for his rap career than his painting and operates within a completely different commercial circuit. He’s not represented by any gallery, but his works are frequently purchased by music producers, for instance. This chapter reveals the existence of different art worlds and commercial networks, a theme which is further investigated in “The Salon”, centered around the private contexts in which art operates. It references both 19th-century Paris Salons and the domestic interiors where art is often displayed, as well as the behind-the-scenes dynamics – private dinners with gallerists and collectors – a part of the market restricted to the wider public.

EB: Moving on, one enters “The ‘Gift’ ‘Economy’”, where the context, rather than the motifs painted, take center stage.

PP: Here, we feature works by Agata Słowak and Łukasz Radziszewski. Słowak, a well-known artist represented by Poland’s most important gallery and whose works sell for significant sums, presents portraits that were actually given away and never functioned within a commercial context. In Radziszewski’s case, we dive into the story of patronage: his works were painted with a specific collection in mind, commissioned by a blueberry grower from the Podlasie region. In this chapter, the context is paramount, but interesting formal nuances also emerge. Agata’s painting language has remained consistent since the early days of her career, but it shifts depending on the recipient. For example, a painting created for a partner becomes an intimate self-portrait, while a portrait of a female curator from her gallery adheres more to the conventions of representative Renaissance portraiture.

EB: Before we wander further: even though this is the first exhibition you’ve worked on together as curators, you seem like a very harmonious duo. A good team. I’m curious about your work dynamics – how did you collaborate on this show?

JO: We work together at the Museum of Literature in Warsaw, so we see each other every day. We’re both art historians with a shared passion for analysis and art, and we’re similar in age. We’re friends. So we thought, why not try doing something together? It felt completely natural. I definitely couldn’t have pulled off this exhibition alone.

PP: It’s like in one of those cliched situations: two white guys talking over a beer, and ending up deciding to do a podcast. Our case was similar, but instead of a podcast, we ended up with an exhibition. But jokes aside: I find these conversations very valuable. It’s helpful to challenge your own intuitions and justify your choices. It really helped crystallize the exhibition concept.

JO: Dialogue prevents you from becoming too entrenched in your own ideas. Listening to someone you trust is crucial, and it also allows for compromises that ultimately make the exhibition stronger. We didn’t have a specific method for developing the exhibition, the method was to go to the pub after work and talk. The conceptual framework actually emerged during one of those sittings. I would say that the key to a good show is people who get along well.

EB: Your shared admiration for art is clearly visible in the show. Each of the works is treated with respect and carefully integrated into the exhibition’s chapters. But in addition to being a show about painting, it’s also a show about the artists themselves.

JO: We are lucky enough to have worked with exceptionally creative and conceptually mature individuals. I was referencing my disappointment with remakes overflowing contemporary culture. Still, there are artists that do not stop at looking back at history, but appropriate it and make it their own. One such case is Ant Łakomsk, shown in the chapter “On the Shoulders of Giants.” She has a very rare and bold approach. In her piece, she directly copies a painting by Gustav Klimt – an early landscape of a lake, which you wouldn’t immediately associate with his more iconic works. She takes that painting, scales it up almost twice its size, and uses it as a backdrop. But for her, this Klimt – already “Klimt” in quotation marks – becomes a stage for her own story, epitomized by a cartoonish image of two girls, almost as if painted on glass.

EB: History becomes a resource to draw and learn from, so it’s not repeated. In the show, some artists turn their gaze forward and the future becomes a resource as well.

JO: This is the case in the final chapter, which we called “Digital Resources.” Here, we consider how new technologies affect the materiality of the image, meandering between the two extremes that pop up when discussing artificial intelligence: either the idea that AI will soon take over painters’ jobs, or the glorification of AI as just a tool for tech enthusiasts. Artificial intelligence is undoubtedly getting smarter, and this is a phenomenon we can’t ignore. However, it’s hard to imagine that AI will completely replace artists who use paint. In this context, we present a work by Norman Leto that directly engages with how AI creates images. Essentially, Leto uses paint to poetically respond to what AI does when generating images. The artist gives the AI a prompt based on his dream visions, and then, based on what the algorithm produces, transfers the image onto a canvas.

On the other hand, Tymek Borowski borrows from internet memes, creating a sort of pseudo-content from the online world. Both artists, in different ways, engage with the idea of the artist’s presence in the work. Leto seems to believe that the artist can slowly step back as the author, creating the initial concept and then allowing the AI to take over the conceptual effort. In contrast, Borowski withdraws even more completely from direct communication, leaving us with a series of almost nonsensical signs or gibberish. Yet, through his brushwork, he emphasizes the painterly gesture – suggesting that even in withdrawal, the artist’s presence is still felt.

EB: This seems like an interesting comment on the myth of the genius – an enduring myth, still very much alive, and often harnessed by market dynamics.

PP: The discussion around this notion is quite fascinating. On one hand, there are theories that explain the concept of genius in a purely constructivist way – seeing it as the result of a fortunate combination of social factors that shape an artist’s career. On the other hand, there’s the more pseudo-romantic vision: a talent that can’t be fully described or explained, a divine spark, a metaphysical quality. Once more Alberti, emphasizing the need for artistic development, experimentation, and a drive to transcend one’s own creative schemes, offers a much more sober approach, avoiding naïve simplifications.

EB: We return to Alberti. Art history offers a lot of really good advice it seems.

JO: We’ve already touched on a few points, although I’m well aware that giving advice to artists can seem out of place. Alberti was very conscious of this, but he also took artists seriously. Still, there are a few suggestions that contemporary painters should consider. For example, at the height of one’s career, one shouldn’t focus solely on gaining more “money and fame,” because that rarely leads to lasting satisfaction. What truly matters is constantly seeking new forms of expression, exploring new territories, and learning. You have yourself, your imagination, your paints, and your brush. You’re standing in front of the canvas, in the studio, with endless possibilities at your disposal. Why not explore them?

[1] Józef Chełmoński (1849 –1914) was a Polish painter of the realist school with roots in the historical and social context of the late Romantic period in partitioned Poland. Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J%C3%B3zef_Che%C5%82mo%C5%84ski .

Artists: Zuzanna Bartoszek, Tymek Borowski, Patrycja Cichosz, Jagoda Czarnowska, Veronika Ivashkevich, Wiktoria Kieniksman, Józef Kluza, Marian Kopf, Tomasz Kręcicki, Norman Leto, Ant Łakomsk, Cyryl Polaczek, Mariola Przyjemska, Łukasz Radziszewski, Agata Słowak, Paweł Susid, Michał Żytniak

Exhibition Title: Don’t Hate the Player, Hate the Game

Curated by: Janek Owczarek, Piotr Policht

Venue: Galeria Bielska BWA

Place (Country/Location): Bielsko-Biała, Poland

Dates: 08.11.2024 – 05.01.2025