Kasia Sobczak

It’s mid-October in Gwangju, South Korea’s fifth-largest city. The buzz and excitement surrounding the early September wave of art events such as the third edition of Frieze Seoul and the 23rd edition of Kiaf SEOUL, new exhibitions at several international commercial galleries in the capitol, along with the opening of 15th Gwangju Biennale, have subsided, and the art world’s attention has shifted elsewhere, to other art fairs and events on other continents. The pace of interest is brief but intense, leaving the city’s art spaces pleasantly quiet and sparsely visited. The reviews I read before attending the 15th edition of the biennale, in major art magazines like Artforum, e-flux, or The Art Newspaper, had already shaped my expectations for the event – stay alert, look for details in artists’ works, immerse yourself in the rhythm of the show and get ready for a poetic, ephemeral experience. The cluster of aforementioned openings, including that of the Biennale, has sparked conversations around the shifting power dynamics in this scene and the more global implications. It prompts a reflection: when did it become popular for the West to look in the direction of South Korea? And how are events like the Gwangju Biennale shaping the cultural landscape of South Korea and East Asia?

The origins of the biennale trace back to the early 1980s, during a period of intense political upheaval. The Gwangju Uprising, locally known by the date of its occurrence, May 18th, placed the city at the forefront of the country’s fight for democracy. The demonstrations were brutally suppressed by the police, causing several deaths and cementing May 18th as a symbol of liberation and resistance. The biennale was originally founded to commemorate these events, as a platform for experimental contemporary art that engages with social, cultural, and political issues and human rights. Since the mid 1990s, it has gained a reputation as a forward thinking, politically engaged, intersectional event, shaping the South Korean art scene as well as global biennale discourse, as it is the oldest biennale on the continent.

This year’s biennale, with artistic direction by Nicolas Bourriaud – the theorist who introduced us to relational aesthetics in the 90s – and curated by Barbara Lagié, Kuralai Abdukhalikova, Sophia Park, Jade Barget, and Euna Lee, presents an exhibition with a seemingly Eurocentric, Western lens. Titled PANSORI: A Soundscape of the 21st Century, the exhibition explores the interplay of space and sound, anchoring its narrative within this distinctive thematic context. Bourriaud’s reference point was the 17th century Korean term of pansori, which as we read in the text accompanying the main show ‘’literally means the noise from the public space.” “(…) the 15th Gwangju Biennale intends to recreate the original spirit of pansori, presenting artists who explore contemporary space through dialogue with the living forms around them.’’ The main exhibition was spread throughout the city of Gwangju, inviting visitors to explore the biennale hall, local museums, and various off-site locations, including a traditional hanok village, and vacant buildings that hosted site-specific installations. The visit becomes a sort of a treasure hunt, enhanced by navigating between national pavilions, most of which were hosted by cultural institutions or foundations collaborating with national institutes. This year’s theme resonated across the main locations, which were unified by the pervasive influence of their omnipresent soundscapes. What was also distinctive and repeating was the motive of linking Gwangju to Seoul in the experience, even though the cities are more than 200 kilometers apart. While reading the aforementioned reviews, it was challenging to think about how such an extensive presentation (72 artists in the main exhibition and 31 national pavilions in Gwangju alone), could work.

My journey began at the biennale hall, a three-story venue featuring five distinct exhibition spaces and a café, nestled between towering residential blocks on one side and a serene museum park on the other. The square in front buzzed with the energy of teenagers and organized groups of senior Koreans visiting the venue. Throughout the visit I noticed a consistent presence of volunteers and elderly attendees diligently scanning artwork labels and using the QR codes to find more information on their smartphones. This scene prompted me to reflect on broader concepts and mechanisms of audience development and the accessibility of contemporary art across different generations – topics that are frequently discussed yet often underdeveloped or neglected. However, my impression here is quite the opposite. Many times, the indication of success is measured by quantity rather than quality, and it makes me wonder if this narrative is reflected in the curatorial decisions at all and who is the actual audience of this biennale?

The five galleries within the venue were thoughtfully divided into sub-themes, each exploring narratives centered on the effects of sound. The show started with a symbolic walk through Oju 2.0 (2022), an immersive, multisensory installation by Nigerian artist Emeka Ogboh, featuring a dark tunnel infused with dynamic field recordings from a neighborhood in Lagos. The recordings were synchronized to an ambient orchestra resembling the chaos and harmony of urban environments. This was followed by Brazilian artist Cinthia Marcelle’s work Não existe mais lugar neste lugar (There is No More Place in This Place) (2019-2024), a fluorescent white room and semi-collapsed office ceiling panels – a poignant metaphor to the space/non-space known to many workers – an architectural gesture reflecting the organization of collapsing social structures in modern workplaces.

The experience is accessible and digestible, offering a concise walk-through that avoids overwhelming visitors with dense intellectual texts or overly complex scenarios. The exhibition unfolds throughout the spaces, continuously shifting in both physical and auditory form. There is also an introduction to what will be seen and experienced in several other locations scattered across the city, which are considered part of the main show. Some artworks are divided and presented in several locations, creating different contexts for the works. Other pieces take the form of large-scale installations that operate on specific schedules and spatial dynamics. This layered approach to the presentation creates an evolving dialogue between sound, space, and the city itself.

Parallel to the main exhibition is the Pavilion Project, which began in 2018 with three countries as a way to create international exchange and generate new audiences. In 2023, there were nine. This year, the project tripled in number to thirty one, mostly through adding a variety of foundations and organizations from other Asian countries, presenting their shows in partner locations throughout the city. Unlike the national representations in the Venice Biennale for instance, these exhibitions are often organized by other national entities. In theory, the presentations were intended to align with the concept of the pansori opera while also addressing the issue of climate change from Bourriaud’s calling, offering diverse perspectives on the theme and fostering international dialogue.

I walk through the main hall and try to be attentive to artists coming from East and Central Europe. There are few from Russia but I don’t see any from Ukraine. It’s also notable that unlike the previous edition, there was no Ukrainian pavilion among the national presentations this time.

Among artists from Central and Eastern Europe, several stood out as personal highlights. One such work was the installation DIY (2023) by Lithuanian artist Anastasia Sosunova, whose work folds the history of Lithuanian neo capitalism in the 1990s into the narrative of a road trip, inspired by the persona of Augustinas Rakauskas – founder of a group of companies of DIY stores in the Baltics, who later assumed the role of a spiritual leader. Sosunova’s work is composed of video and sculptural installation, in which by working with micro-histories, she unravels broader social-cultural phenomena.

In his work Neophyte III: On the Eve of the Shortest Night (2019-present), Belarusian artist Jura Shust revisits the Slavic myth of Kupala Night – the summer solstice celebration as a form of communication between powers of nature and contemporary technology. Central to the installation space is The Neural Seedlings (2024), a series of machine-sculpted spruce wood panels that symbolize the networked interplay between AI-driven communication and non-human species. The entire space exudes an enchanted atmosphere, evoking a deep connection to human emotions while bridging the natural and the technological.

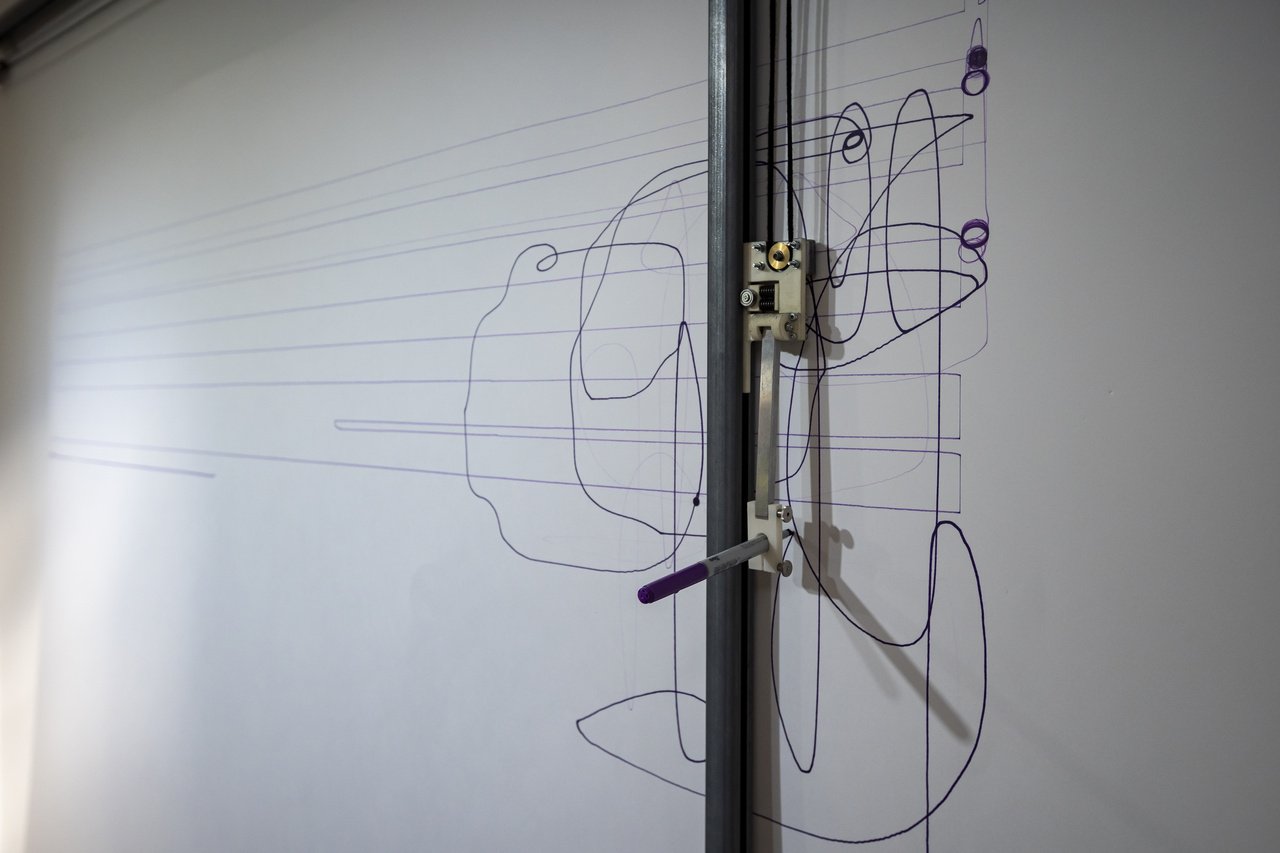

In contrast, Polish artist Agata Ingarden’s work delves into post-humanities and science-fiction, weaving these themes with mythical narratives. The artist invites visitors to The Dream House World (2021 –) an ongoing installation, which mirrors our mental architecture, functioning as a techno-organic ecosystem. Here, visitors are inside a corporation, one which operates independently of its users. The coldness and obscurity of the surrounding window blinds is contrasted by the familiarity of video games and a talkative mushroom. UV prints on oxidized copper evacuation plans and maps are subtly embedded, adding to the layered narrative of this surreal and thought-provoking space.

American artist Max Hooper Schneider’s LYSIS FIELD (2024), situated on the top floor of the hall, encapsulates many of the contexts explored throughout the exhibition. The oversaturation of forms, ideas, and materials mirrors the ambiguity and complexity observed in much of the preceding spaces. Hooper Schneider’s work combines beauty and horror, capturing the essence of a world in transformation – natural elements, technology, synthetic waste, vibrant colours and humans strolling through the imagination of the post-Anthropocene era.

In the Yangnim-dong neighborhood, which is located in the southeast part of the city – almost one hour by public transportation from the mail biennale hall – the exhibition extends to several off-site spaces; amongst them, an empty mid 20th century family house and the abandoned ruins of an old police station. In the former police station we have the work of French artist Saâdane Afif, Pavilion of Eternity (2024), drawing inspiration from Arthur Rimbaud’s poem Eternity, serving as a transitional space for the Gwangju Biennale and a series of concerts of pansori singer Sora Kim. It’s a meeting point between the audience and the artwork with the spirit of absence and history of the location. Here, Bourriaud’s concept of mixing sound and space takes shape in a series of performances and graphic images inside the station. At the same time, Yangmin-dong inhabitants are fighting against gentrification, making this possibly the last chance to see this historically significant area in its current form. During my visit, a group of local residents were gathered around a weeping willow tree by the central roundabout, celebrating the tree’s history as the remaining natural element and origin of the neighborhood.

Mira Mann, who explores imaginary worlds through space, image, and multimedia environments, occupies the abandoned family house by presenting several artworks, not far from the former police station. Reflecting on their personal story, the German artist examines individual understanding of the past and memories, inviting visitors to mark the walls using the brush and ink left in the space, and to immerse themselves into the pansori audio composition in the video work mother may recall another (2022), which plays inside the living room.

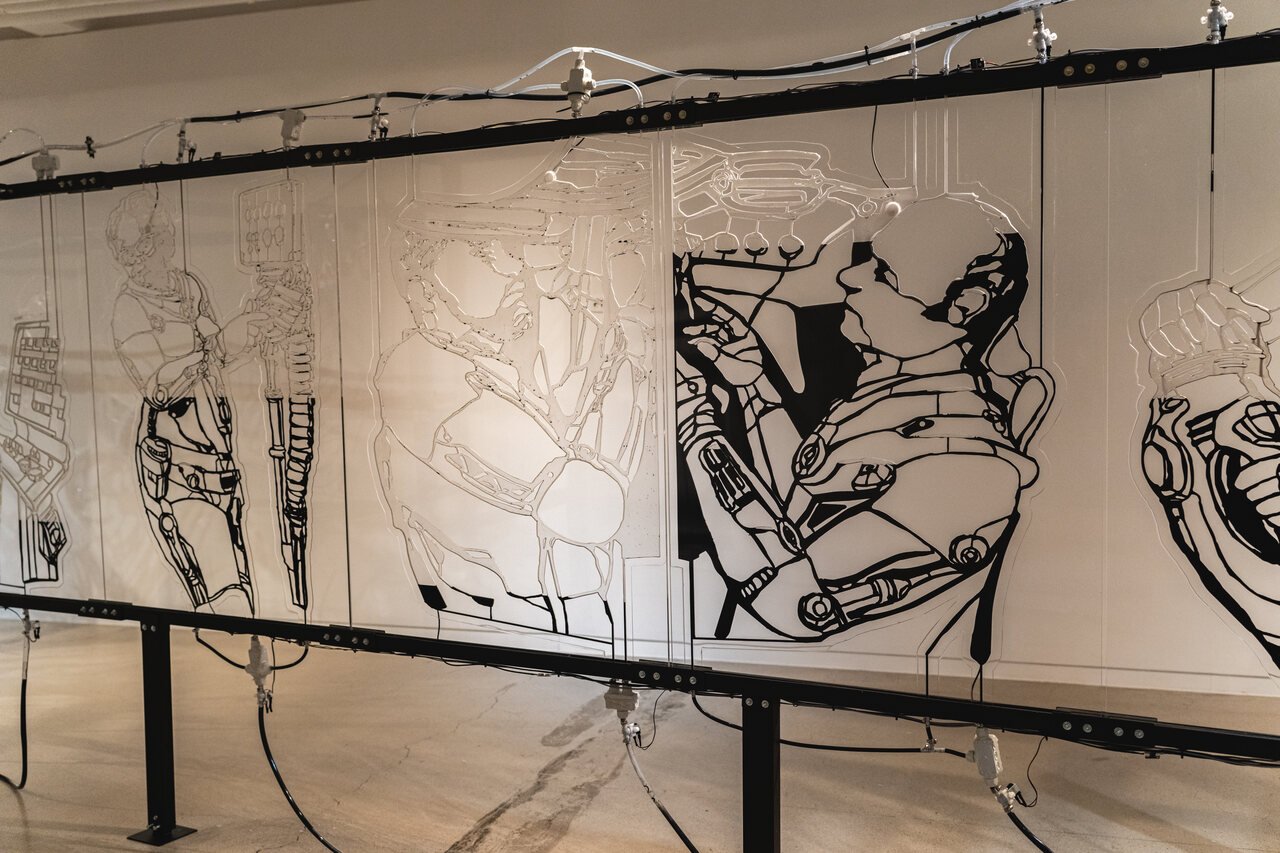

Just a few steps from here is the Polish Pavilion at the impressive building of Leeleenam Studio, which was organized by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute and is also the sole pavilion from the East and Central European region. Katastematic pleasures showcases Polish artists whose work spans across time – past, present, and future. The titular pleasures refer to ancient Greek philosophy, describing “a state of letting go of unnecessary desires, anxieties and activities, while indulging in spiritual and intellectual pursuit.” The opening piece, remember (me), by Przemysław Jasielski, employs a custom technique of lucidography to simultaneously present the past and future of FSO (Fabryka Samochodów Osobowych/Passenger Car Factory), a car manufacturing company in Warsaw currently owned by the Korean company Daewoo, depicting how the future of humans and machines may look. Within the pavilion, the socialist history blends with meditative and technologically-enhanced reflections on the present. Among these works, Alicja Klich’s question: “who is art really for?” is the central point of reflection – for the pavilion and for my time in Gwangju this year. For me, the show ends with the most pleasant sound artwork of the whole biennale – Maciej Markowski’s soundless sound sculpture – a music composition played through speakers suspended in a vacuum chamber experienced only by the eye, allowing the revival of my thinking, enabling me to hear my own thoughts.

The 15th Gwangju Biennale offers a multitude of ideas and propositions for the future, while selectively looking back at the past, which begs a lingering question in consideration of our present moment: is there room for a biennale that embraces softness and vagueness in its selection of artworks? It is a critical choice: to confront the pressing and immediate matters of the global socio–political agenda, or to instead give the audience space for temporal escapism, in a time when the world is quite fraught. The overall selection of artworks and curatorial approach conveys an impression of subtle interventions and symbolic gestures that seem insufficient in addressing Bourriaud’s callings in the inaugural manifesto. The lack of political straightforwardness might be a conscious strategy, yet for this biennale in 2024, it feels like something urgent is slipping between the fingers and I just can’t quite reconcile it. Particularly given the context of the origin and development of the biennale as a metaphoric continuation of the legacy of the May 18 Gwangju Uprising. As a leading event of its kind in South Korea and East Asia, the biennale plays a significant role in shaping the international cultural profile of the country and region, and to achieve this, they must remain alert and responsive to the influences and needs of both global and local artistic communities and audiences.

Artist: Haseeb Ahmed, Deniz Aktaş, Noel W. Anderson, Andrius Arutiunian, Kevin Beasley, Wendimagegn Belete, Bianca Bondi, Dora Budor, Peter Buggenhout, Angela Bulloch, Alex Cerveny, Cheng Xinhao, Choi Haneyl, Gaëlle Choisne, Anna Conway, Binta Diaw, John E. Dowell Jr., Hayden Dunham, Liam Gillick, Loris Gréaud, Matthias Groebel, Matthew Angelo Harrison, Marguerite Humeau, Agata Ingarden, Hyejoo Jun, Hyoungsan Jun, Hyeongsuk Kim, Jayi Kim, YoungEun Kim, Dominique Knowles, Agnieszka Kurant, Hyewon Kwon, Netta Laufer, Brianna Leatherbury, Yein Lee, Oswaldo Maciá, Mira Mann, Cinthia Marcelle, Vladislav Markov, Beaux Mendes, Myriam Mihindou, Na Mira, Saadia Mirza, David Noonan, Katja Novitskova, Josèfa Ntjam, Emeka Ogboh, Frida Orupabo, Lydia Ourahmane, Mimi Park, Philippe Parreno, Amol K Patil, Harrison Pearce, Lucy Raven, Tabita Rezaire, Marina Rheingantz, Marina Rosenfeld, Max Hooper Schneider, Franck Scurti, Soomin Shon, Jura Shust, Sofya Skidan, Anastasia Sosunova, Jakob Kudsk Steensen, Sung Tieu, Julian Abraham “Togar”, Unmake Lab, Yuyan Wang, Ambera Wellmann, Kandis Williams, Phillip Zach, Saâdane Afif

Exhibition Title: Gwangju Biennale

Curated by: Nicolas Bourriaud (Artistic Director), Barbara Lagié, Kuralai Abdukhalikova, Sophia Park, Jade Barget, Euna Lee

Venue: Gwangju Biennale Exhibition Hall, Yangnim Culture Center, Podonamu Art Space, Han Boo Chul Gallery, Han Hee Won Museum of Art, Yangnim Salon, Yangnim Old Police Station, Empty House, Horanggasinamu Art Polygon, Gwangju Biennale Pavilion (31 separate locations)

Place (Country/Location): Gwangju, Republic of Korea

Dates: 07.09–01.12.2024

Photos by: Please see individual images for credits