Lizaveta German

In the early 2010s, Yuriy Sokolov walked into Efremova26 Gallery, which shared a wall with his house on 24 Yefremova Street. The gallery space in the abandoned villa was given to the artists of Open Group, then emerging and now, internationally renowned. The villa was offered to the artists in early 2013 by unknown owners and abruptly taken away after ten months of operation. This move of temporary generosity could be explained by the local fame of another space founded by Open Group earlier in 2011 – Detenpyla gallery. A semi-basement room in an old apartment building, the room was used as a kitchen for several years by artist Yuriy Biley, who resided there. Since 2011, this kitchen has also functioned as a gallery space for exhibitions of well-known and emerging artists ranging from renowned masters such as Vlodko Kaufman to students of Lviv Art Academy.

For more than 13 years now (quite an unimaginable figure for the inconsistent institutional scene of Ukraine), Detenpyla has been a continuously functioning exhibition venue with no budget and quite a rigorous approach to exhibition aesthetics. It has been a key meeting point for the generation of artists in their 20’s and 30’s, for those visiting Lviv who are willing to dive into its art scene, and also for connecting people remotely. In 2013, the Detenpyla community organised a Skype call (or, I would rather describe it as Skype party, years before the COVID era) with the Kharkiv community around SOSka collective and their eponymous off-space in Kharkiv. The so-called gallery-laboratory SOSka existed from 2005 to 2012, and the collaboration with their peers in Lviv in 2013 was a kind of a farewell event.[1] Established by Mykola Ridnyi, Anna Kriventsova, Bella Logacheva and Lena Polyashchenko in a small building in Kharkiv’s downtown, for years the gallery-laboratory was not only crucial but it was, in fact, the only spot for young artists and musicians to exhibit, self-educate, party, and simply come together. The Skype call was a part of Days of Apartment Exhibitions, a DIY festival that united similar initiatives in Lviv. Detenpyla was at the core of this movement, but definitely not the only one on the scene.

Back in Lviv, another kitchen became a venue for another Open Group member, Anton Varga, during the winter of 2012–2013. During the 89 calendar days of winter, Varga opened a new show every night, documented it, and published it online in a blog called the 89 Days of Winter project. And artist Liubomyr Sikach organised a temporary space in his car-less box in a shared garage area to exhibit his recent works after a long break in his artistic practice. Garage gallery existed for three months in Autumn 2012, but despite its short run, was still crucial in its own way.

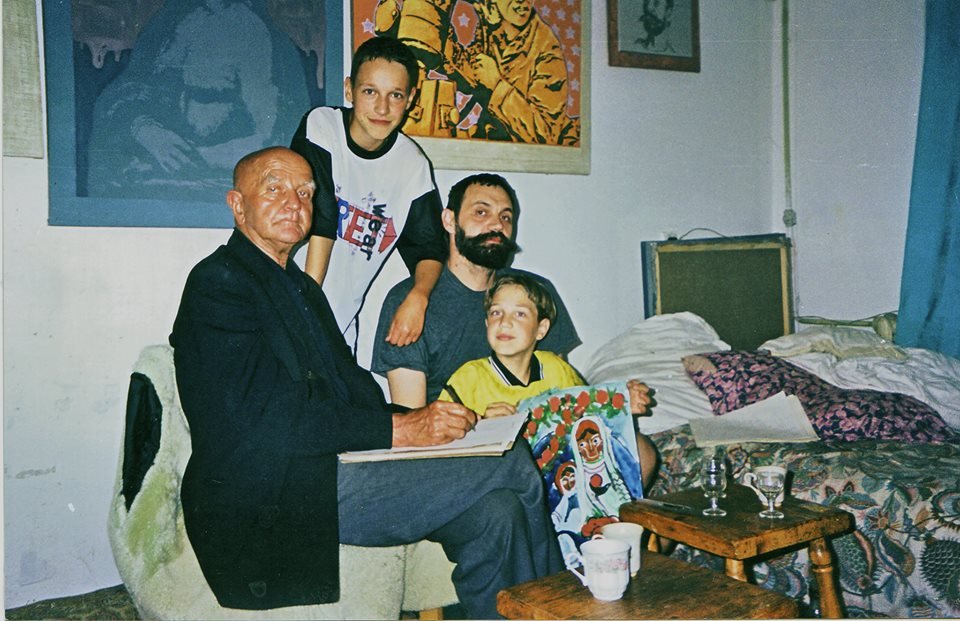

The temporary nature of this type of space was also fundamental to Korydor Gallery’s Temporary Exhibition project that took place every three months on the first floor of the former artistic combinate building in Uzhhorod, a hometown for many Lviv-based artists. Korydor Gallery is not mentioned in any city guide, and when asking citizens about the address, local artists might ironically object that it’s not a gallery but a corridor that leads to the studio of Pavlo Pavlovych. “Pavlo Pavlovych” is the legendary artist Pavlo Kovach, who initiated the corridor’s transformation into Korydor Gallery in the summer of 2002. The gallery was launched with an exhibition in memory of Pavlo Bedzir, a key underground artist of the 1960s–70s, and friend and mentor to Pavlo Kovach. His studio used to belong to Bedzir, whose works have been carefully stored there.

Temporary Exhibition, a format that exclusively accepts artworks that may be exhibited only once and only here, was initiated by artist Petro Ryaska in 2012. In 2016, he also started the private residency in Uzhhorod, Sorry No Rooms Available, which has been operating in one of the shabby yet charming vintage rooms of the late soviet Intourist-Zakarpattya Hotel. Again with almost no budget, but with tremendous enthusiasm, Ryaska has been able to get artists from all over Ukraine and abroad acquainted with the “sunny Transcarpathians” as locals tenderly call their region. His enthusiasm has been rewarded, though under tragic circumstances. Since the full-scale war, his residency has become one of the significant safe harbours for internally displaced artists from all over Ukraine. Because of this, he has received several big international grants, enabling him to finally fund this project.

A remarkably permanent space, along with Detenpyla, is the informal gallery called tymutopiapres, which was established in 2011 in the garage of artist Liubomyr Tymkiv’s private house in Lviv’s Medova Pechera (Honey Cave) neighbourhood. Tymkiv hosts several events a year, presents projects of his fellow artists and parts of his collection. Due to Tymkiv’s great interest in mail art, the gallery’s programme has a truly global dimension. Acquaintance with Liubomyr was one of the turning points and genuine inspirations for our curatorial duo together with my long-term partner in crime, Maria Lanko. We wondered how he managed to keep his space up in such a remote location without the flow of an “art crowd.” “I love this closed space – he said unpretentiously – it does happen that I open a show and nobody visits. Then I imagine only flies coming in from the yard to see it. It’s one of the features of an alternative gallery. It produces a certain layer, and it doesn’t matter if only those flies saw it. It starts to live its own life: you only need to start the process, and the quantity of visitors does not influence it.”[2] Interviewing him from his cosy kitchen, his point struck us explicitly. To illustrate the extent of our fascination, I can’t resist mentioning our first independently organised exhibition (hosted by another vacant space, run by artist Adam Nankervis in Berlin). It was solely devoted to the history of informal galleries of Western Ukraine, and was titled If Only Flies Saw the Show, Does It Mean That It Actually Happened? and had a subtitle that thoroughly explained its content: Informal spaces and artistic practices of Western Ukraine between bodies, studios, conversations, actions and memories.

Tymkiv still operates his space. When I visited him in May 2024, he showed me a notebook with sketches, notes, and dried flowers by artist Denys Pankratov, who now serves in the Ukrainian Army and fights on the frontline. It is also worth mentioning that Tymkiv is a war veteran who fought in the russo-Ukrainian war in 2014-15. During his service, he managed to create new works from found materials and, unbelievable as it may sound, he even organised small shows in blindages. Today, his garage still has its warm, marginal vibes. But it is no longer invisible – foreign visitors curious about the local scene will most surely be brought here by local peers.

Back in Lviv, one of the other founders of Open Group and Detenpyla, Pavlo Kovach Jr. (the son of Korydor’s Pavlo Kovach), was among those who actively promoted the idea of establishing a municipal art centre in Lviv. In 2020, after several street protests, a dialogue was established with the city council and Lviv mayor Andrii Sadovyi. The city-funded Lviv Art Centre opened its doors in a 19th-century space led by art manager Liana Mytsko, and was curated by Kovach Jr. and artist Oleg Suslenko. This has become one of the most successful art community cases of a partnership between the city and local grassroots movements, which was in part instigated because of Mayor Sadovyi’s visit to Detenpyla.

During the first several months of the full-scale invasion, the Lviv Art Centre served as a hub for internally displaced people who fled to Lviv, seeking shelter or making a transit stop on their way to the EU. Warm meals and psychological help were offered 24/7 while Pavlo Kovach Jr. and his partner, jewelry designer, Myroslava Kozar, drove back and forth to the central railway station, picking up disoriented people arriving from all around the country. In 2023, Kovach Jr. left his curatorial position for the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Parallel to his service, he also oversaw the opening of Welcome to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Kherson 2002–2022. As the title hints, the show presented two decades of history and the collection of the private museum founded by artist and curator Vyacheslav (Slava) Mashnytsky, who was abducted by russians from his home in Kherson at the onset of the full-scale war. To this day, Mashnytsky is counted as a missing person. But his friends and peers, including the exhibition curators Semen and Rina Khramtsovy, took care of the evacuated museum’s legacy. Ironically enough, the Museum of Contemporary Art Kherson, which grew out of a small artistic initiative in Kherson, can now be counted as one of the longest-existing institutions of contemporary art in Ukraine.

Though this city has not been considered among the mainstream cultural centres of Ukraine, it has in no way been idle artistically. Mashnytsky was not alone in his work; there has been quite an outstanding community of filmmakers, writers, and multi-media practitioners that have been united by Totem – a center for cultural development, which was established as early as 1996. Home to many important artists like Stas Voliazlovsky, Olena Afanasieva, Max Afanasiev, and Viacheslav Poliakov, among others, the Kherson community even developed its ironic art movement called “kher-art” (where kher- stands for the part of the city’s name but also for a Ukrainian translation of “cock”). The self-organisational impulse kept the Kherson scene sustained for almost 30 years, so much so that it was strong enough to keep it alive even during the nine months of russian occupation from March – November 2022. This can be exemplified in the work of Yulia Manukian, a local critic and curator, who was documenting the working process of six artists who stayed as a group and later individually, when it had become too dangerous to gather. Manukian recorded their activities on-site and then remotely when she escaped the city.[3]

What unites Kherson, Lviv, and Uzhhorod’s endeavours, and makes the Kherson museum show look quite natural in Lviv is that they all exist beyond conventional art system regulations and outside art market interests. Each makes its way, often unpredictable, while their future greatly depends on external circumstances and personal whims. However, when researching more in-depth, those spaces and collections of art, documents and artefacts – organised, chaotic, digitalised, ephemeral – constitute the most exciting and unprejudiced sources of knowledge covering the Ukrainian art scene. And this is true, I dare say, for both before and since the full-scale invasion. In both Kherson, Uzhhorod, and Lviv, this tradition of here-and-nowhere underground spaces and collectives has contributed to a specific type of artistic thinking.

What also connects these various alternative exhibition-making practices, before and after 2022, is a stubborn intention to escape the uniforming environment of the white cube – and for a good reason. A white cube space, as prototyped by MoMA’s founding director Alfred J. Barr in the late 1920s, typically reduces interconnection with the outside world. Its windows are banished so that, as Elena Filipovic argues, the semblance of daily life, the passage of time, and context disappear, noise and clutter get suppressed, and general sobriety reigns. Moreover, she continues, “Particular to the white cube is that it operates under the pretense that its seeming invisibility allows the artwork best to speak; it seems blank, innocent, unspecific, insignificant. Ultimately, what makes a white cube a white cube is that, in our experience of it, ideology and form meet, and all without our noticing it.”[4] In other words, the neutral (or seemingly neutral) area for hanging and installing artworks, free from “noise and clutter,” tries to veil and neutralise the outside world, the physical and political, leaving the viewer face-to-face with artwork in (what is imagined to be) its pure entity. Since its introduction, the white cube format has been used as intensely as it has been criticised by international artists, curators, and institutions alike. But what has recently happened in Ukraine is scraping the last sacred bits of the white cube as such. Since “clutter”, “noise”, and “context” of wartime reality are not just immovable, but rather they are, in the end, what makes today’s art shows in Ukraine so different, and perhaps so appealing, if you would excuse such a playful art history quote.

Many significant shows in Ukraine since 2022 have had their backgrounds exposed and “cluttered” – and they have spoken volumes about the broader context for the work and of the people who have put them together. Home to the most sophisticated collection of European and Asian classical art, the Khanenko Museum, under the directorship of Yulia Vaganova, evacuated its collection (same as most national museums in the country) and (unlike most) invited contemporary artists to work out the situation of this spatial and conceptual void. The flamboyant interiors of the Khanenko Museum underlined the emptiness of its vitrines and pedestals, and was the setting for Meanwhile, at the Khanenko House (March 10 – April 30, 2023), a group exhibition curated by artist Katya Libkind.

The walls of The Naked Room gallery, on its own, were always far from white cube aesthetic standards, covered with tiny holes from nails left after countless exhibition de-/installations. This minor interior detail became an eloquent feature during the exhibition Other Parts In The Next Quarter, curated by Borys Filonenko in September – October 2022. The gallery walls were not a mere backdrop but provoked an involuntary association with a torn Ukrainian landscape, in dialogue with the participating artists’ contributions. In Yaroslav Futymskyi’s work, particularly a poem and graphic lines scribed with a pencil, those dotted walls were also reminiscent of houses and fences perforated with bullets and shrapnel. According to Filonenko’s introduction to the show, “It’s questioning how the environment narrows and expands inside a war-torn country: a landscape in transition, tattered, dissolved and marked, abandoned and crowded, experienced anew.”[5]

Even Kadan’s show in the classical white cube space of a successful commercial gallery escapes in a way the notion of a white cube since any underground space (and Voloshyn gallery is a semi-basement type of premises) functions as a shelter today. Not to mention that the “noise” sneaks into any space. Whether air alerts, explosions, or the humming of movable power stations on the streets that supply energy during blackouts, the sounds of wartime daily routines are present in any kind of space – private and public, wealthy and underfunded, sterile and white or dotted with nail holes.

The last point to cover is the re-emergence of exhibitions in private apartments – like Oleksandra Pogrebnyak’s Thickets, Groves, Woods and Bushes and Milk for Teo – which underline how the notion of home, its magnitude and fragility, has been transformed in times of forced relocation, destruction, and even the total elimination of cities. Pogrebnyak’s two exhibitions opened on the same day, February 24, 2023 and 2024 respectively. By opening the show on the anniversary of the full-scale invasion in 2022, in her family apartment in Kyiv, among their books and plants, she made another very poignant and intimate gesture – reclaiming her rights to celebrate this date, which also happens to be her birthday.[6]

As a finale for this essay in two parts, where I managed to cover a good deal of essential cases, yet definitely not all of them, I cannot skip the most extreme example of an apartment exhibition that we have witnessed thus far: a candid example of a complete (and violent in its circumstances) withdrawal from the white cube and, if I can put it bluntly, from a cube as such – as a protected exhibition space with clear outlines of floor, walls, and a ceiling. The show Everyone is Afraid of the Baker, But I Am Grateful was put together by Kateryna Iakovlenko in what was left of her apartment in Irpin after the remnants of a russian rocket hit the building and burned it down during the siege of Kyiv oblast early in 2022, after Iakovlenko had fled. It was accessible for one day only, August 26, 2022, and had a viewing capacity of 50 friends. But the photo documentation that spread around the Internet, as well as an essay[7] by Iakovlenko with her private insights of what it meant to make that exhibition happen, left a piercingly profound impression. The works included graphics by Stanislav Turina and photo prints by Sasha Kurmaz on the bare brick walls, along with subtle textiles by Tamara Turliun next to an empty window hole, and other beautiful pieces by a small group of artists.

There’s no such thing as “what if” in the discipline of (art) history. We cannot judge, really, if any of the shows and venues described here were decisive for how the broader, more traditional and perhaps more reliable art historical narrative has been unfolding. This essay’s grassroots story is quite ephemeral and based frequently on myths rather than scrupulous descriptions. We have no records of conversations between Lamakh and Havrylenko. Surprisingly, there are many factual divarications about Odesan exhibitions as many of their participants are still alive and quite outspoken. The spirit of ParKom parties cannot be preserved on archival shelves. And to truly understand the beauty of Tymkiv’s dacha-like gallery one has to visit it personally, descriptions are impossible to match.

But what is the thing that allows us to glue together all these cases, scattered in time, geography, and socio-political circumstance – to imagine them as a certain specifically Ukrainian tradition, maybe even a unique one? There was no direct passage of knowledge. The Sixtiers didn’t leave any testaments for the next generations to keep the tradition of the informal scene alive. The artists of the 1990s mostly hadn’t taught in art academies, and the younger generation were not looking for a chance to establish a connection with their predecessors. Kyivan artists of the 1990s were perceived as market-oriented painters by the 2010s generation, which had only heard some bits and pieces about the squatting epoch. Sokolov visited Open Group’s gallery by accident, and they initially had no idea that Sokolov himself ran a gallery 10 meters and 20 years away.

Maybe this glue is a passion, a word that isn’t normally accepted by academia art history. The passion to cherish and recognise the meaning in “the most unnecessary and surplus sphere” that is art, if to cite the earlier words of Nikita Kadan. And not just passively cherish, but enable to do the same for others, if only the narrowest circle of peers or viewers from the future. The passion to keep doing it under the most unfriendly circumstances like the risk of political oppression, economic crisis, and full-sale war. The passion to invite friends to hang their works in your place next to a KGB office, the passion to keep several snaps of a brief street action for years so that the next generations will learn about Fence Show, the passion to use randomly available ruins as art center substitutes, and the passion to enter the ruins of one’s home and turn them into a site of exposition. Yet again, if we borrow art history’s habit of claiming novelty, I dare say that it was Iakovlenko’s decision to hang some artworks inside the skeleton of her burned house that relaunched the exhibition flow in this war-torn country and inspired many to follow her lead. Her building in Irpin has since been included in the state reconstruction plan, so Kateryna will move back home again soon. I wonder if she will invite us in for a future exhibition?

Thickets, Groves, Apartments, and Garages: on informal exhibitions in Ukraine, 1960s—2022: Part I

The broader preliminary research, of which is much presented in this text, was supported by the Sonderförderung Ukraine Hilfe programme by Bundesministerium für Kunst, Kultur, öffentlichen Dienst und Sport. Unfortunately, due to the obvious limitations of publishing texts, we were not able to give enough, or in some cases any attention to many more important initiatives, spaces, projects, and their creators. But there must be no such thing as a full stop in art history. The research goes on and Part III is absolutely in the author’s plans.

Lizaveta German is a PhD in art history, researcher and curator. She is co-founder of The Naked Room gallery (Kyiv) and co-curator of the Ukrainian Pavilion, 59th La Biennale di Venezia. In 2015, together with Olha Balashova she published a book The Art of Ukrainian Sixties (republished in English in 2021). And in 2017 they co-edited Decommunised: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics book.

This text, published in two parts, is one of four commissioned for Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow, a project implemented by Fundacja Ziemniaki i and Stroboskop Art Space (Warsaw) covering themes related to the production, dissemination, and evolution of contemporary Ukrainian art and culture during active wartime circumstances. Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow is supported by IZOLYATSIA foundation, Trans Europe Halles, and Malý Berlín, and is co-financed by the ZMINA: Rebuilding program, created with the support of the European Union under a dedicated call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced people and the Ukrainian Cultural and Creative Sectors.

[1] The SOSka group: how the community around contemporary art was formed in Kharkiv in the 2000s. Interview with Mykola Ridnyi by Lizaveta German and Svitlana Libet, Your Art, 16.03.2021, https://supportyourart.com/conversations/grupa-soska-yak-formuvalasya-spilnota-dovkola-suchasnogo-mystecztva-v-harkovi-2000-h/

[2] German, Lizaveta and Maria Lanko. Informal Art Spaces of Western Ukraine. Lviv – Uzhhorod. 1993–2013. NIICE Publishing, 2015.

[3] A detailed text about the residency, the participating artists and the works produced is published (in Ukrainian) on Past /Future/Art memory culture platform https://pastfutureart.org/kherson-art-resistance/ and also at The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/jul/23/khersons-secret-art-society-produces-searing-visions-of-life-under-russian-occupation

[4] Filipovic, ibid, p. 64

[5] Other Parts In The Next Quarter, curatorial statement of Borys Filonenko, https://www.thenakedroom.com/en/show/Other-parts-in-the-next-quarter

[6] Oleksandra Pogrebnyak, in conversation with Lizaveta German, 07.07.2023, unpublished

[7] Kateryna Iakovlenko, “Poppies and Hedgehogs,” Apofenie (June 12, 2022)