Dasha Lohvynova

Investigating the opportunities for writing inclusive and critical historiography of Eastern European art, Polish art historian Piotr Piotrowski developed the concept of horizontal art history. Coined at the beginning of the twenty-first century, this term remains influential in challenging the hegemony of knowledge and research within art history, particularly in post-communist spaces. Piotrowski’s notion of horizontality draws attention to the limitations of Western-oriented art historiography, especially when addressing Eastern European or global art histories.[i] The scholar aptly questioned the dominance of Western frameworks that dictate knowledge production and establish canons that cast aside peripheries of art production, such as Eastern Europe. Knowledge and assessment paradigms developed in Western European countries and North America have created complex hierarchies and dichotomies, establishing stylistic norms and values that the marginalized should follow for success or recognition by Western academia and historiography. However, Piotrowski argues that art history in Eastern Europe is inherently horizontal and non-hierarchical: developed in relation to the Western canon, in the region itself, almost no canons or hierarchical ties were previously formed. In studying Western art history and its methodologies, the local is often deemed unnecessary and counterproductive to the contemporary – it is the opposite of the universal, global, and transnational. For Piotrowski, however, the notion of locality in post-communist cultures is more nuanced. In his opinion, it is not simply reduced to the idea of nation and nationalism. Conversely, it is a layered matter that constitutes many processes inside and outside the specific locality. The local, therefore, transcends national ideologies, becoming “[…] something more and something less than the national.”[v] Without a reduction to the essentialism of nationalism, it transgresses borders and ethnicities, and is open to influences from within and outside. Despite the dominance of certain socio-political ideologies that dictated aesthetic regimes, Eastern European art history remains polycentric and multivocal, a reflection of the region’s cultural and artistic diversity that has persisted despite oppressive policies.

While critical discourses such as queer, feminist, and decolonial studies have long challenged Western-centricism in art history – particularly its influence on canon formation, art markets, and rubrics for success – the vertical approach to art history still dominates. Writing and thinking about Eastern European art remains constrained, especially when it comes to the study of art from post-USSR countries, whose art histories are further obscured by the ongoing influence of Russian historiography and its colonial biases. In the Western imagination of the post-Soviet space, artistic developments and origins are often Moscow-centered, which further displaces and marginalizes post-Soviet countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, and the indigenous peoples of Russia, from the global art map. Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Ukrainian art and its history were largely peripheral in Western artistic and academic discourse. While not entirely absent, a noticeable emergence of Ukrainian art on the global art scene has been taking place, tirelessly driven by Ukrainian artists, curators, and academics, supported by a diverse range of largely European institutions and collaborators.[ii]

The inclusion of Ukraine at the European art table takes diverse forms, including decolonial re-assessment of provenance and artist biographies of Russian and Soviet art. Alongside academic endeavors there have also been many exhibitions platforming Ukrainian art, focusing on multifaceted exploration of Ukraine’s history and contemporary developments, which also reflect the current wartime reality. These exhibitions became spaces of knowledge production, fostering connection between Ukraine and international audiences by bridging the physical and epistemological gap. Artistic expressions also turn into activist endeavors, creating critically engaged spaces for audiences to stand with and support Ukraine in its fight for freedom. From an art historian perspective, I believe the global emergence of Ukrainian art represents more than just education or activism.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine triggered not only external conversations about existing narratives of art history but also an internal dialogue among Ukrainian contemporary artists, academics, and researchers. Since the Revolution of Dignity in 2014, and the subsequent Russian annexation of Crimea and invasion of Eastern Ukraine, these conversations have intensified, exploring questions of Ukrainian history, culture, memory, and identity. In the wake of significant political and societal transformations, many Ukrainian artists have turned to the past, attempting to reassemble histories that were disrupted or manipulated by Russian (and Soviet) forces. Artistic practices of the past decade have increasingly focused on archives, reviving forgotten names, stories, traditions, and symbols. This archival turn continues during the full-scale war, with certain recurring motifs emerging: landscape, folklore, mythology, spirituality, and Christian or sacred symbols being the most notable.

Each of these elements represent specific Ukrainian localities, echoing Piotrowski’s emphasis on the local as a crucial factor in researching and writing art histories of peripheries. In the context of Ukrainian contemporary art’s international emergence, these works are a testament to previously unknown (hi)stories and experiences. Perhaps, as Piotrowski pointed out, the locality becomes a space for peripheries to be heard, seen, and centered. Thus, I am led to the question of how much Ukrainian wartime art has challenged existing art historical narratives and whether it has fostered non-hierarchical modes of thinking. Taking Piotrowski’s concept as a point of reference, I will reflect on general knowledge about contemporary Ukrainian art and its recent developments in today’s socio-political context through the work of four contemporary Ukrainian artists working both within Ukraine and across Europe. Although these four artists represent only a fraction of the wartime Ukrainian art scene, I have chosen to focus on their practices because of their engagement with locality; instrumentalizing symbols and narratives to address broader questions.

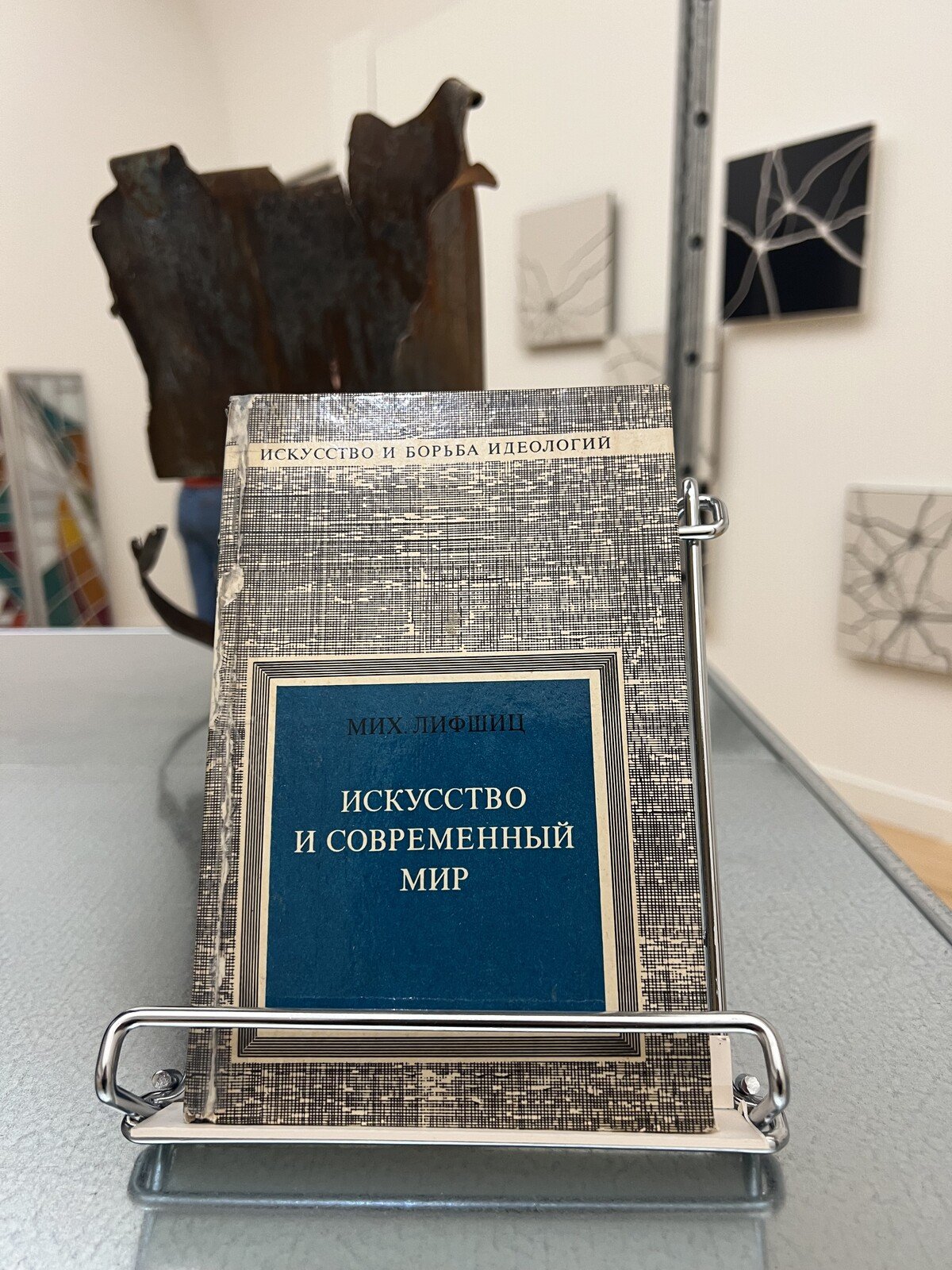

I began thinking about place, and the local in the context of international contemporary art in front of the installation The Possessed Can Witness in Court (2023) by Nikita Kadan, a new-generation conceptual artist from Kyiv who presented the third iteration of this work during the exhibition Kaleidoscope of (Hi)Stories: Art from Ukraine in the Museum de Fundatie in Zwolle. The installation consists of metal racks, reminiscent of the museum’s depot, filled with objects from the past and present: old Soviet artbooks, sculptures of Vladimir Lenin and Taras Shevchenko, plants, fragments of Russian rocket shells, and pieces of destroyed houses from the past two years. Additionally, Kadan incorporates objects from the Museum de Fundatie and also the collection of Dirk Vanhecke. The installation by Kadan, who is well-known for his artistic explorations of post-communist developments and their manifestation in today’s Ukraine, leaves a contradictory feeling: as a viewer, you unpack multiple narratives and memories that meet at the most unexpected intersection. For instance, the Soviet book published in 1978, Art and Contemporary World, from the series Art and Struggle of Ideologies, contrasts with the looted indigenous sculptures from the Dutch museum collection. Ideological struggles appear side by side with reproductions of monuments to Lenin and Shevchenko, one being the “father” of the communist state and the other of Ukrainian national identity.

The Possessed Can Witness in Court touches upon ghosts of the Soviet past while critically addressing broader questions of state memory, politics, and historiography. The installation becomes an archive of unbiased testimony, where objects – displaced from their original contexts, opening up spaces of contradiction – become universal witnesses of complicated histories and the passage of time. Through these juxtapositions, Kadan’s work connects the local Ukrainian experience to the global socio-political community, fostering a sense of shared understanding and engagement through art.

The installation seems intentionally stripped of specific temporal and spatial marking, as the artist does not provide detailed explanations about the place and time of the objects’ production, or their previous functions. Although there is a general label and wall text addressing the work’s overall concept, upon closer inspection, I think the objects themselves reveal the necessary details and translate peculiar local associations. The fragments of war rubble and plants might relate to the universal pairing of death and life, the pain of destruction, and feelings of hope. Yet, the setting of this individually assembled archive still prompts the questions of “why” and “where”, especially in the current political context. This interplay between the local and the global, without strict adherence to national boundaries, is precisely what Piotrowski refers to when discussing the development of horizontal art history.

Ukrainian art historian and curator Svitlana Biedarieva similarly acknowledges the importance of local self-definitions. Discussing the development of artistic practices in Ukraine and the Baltic countries post-USSR, she writes, “[…] art history of Ukraine and the Baltic countries is crafted from the notions and visualities belonging to different ideologies, once suppressed cultural elements, and distorted identities, each proper for its location.”[vi] Thus, it comes to learning from and blending local traditions and national elements with universal and global narratives. Expanding on this, I also see it as a practice of learning from each other’s localities, forming a sense of community, but more importantly – solidarity – that pierces through the periphery.

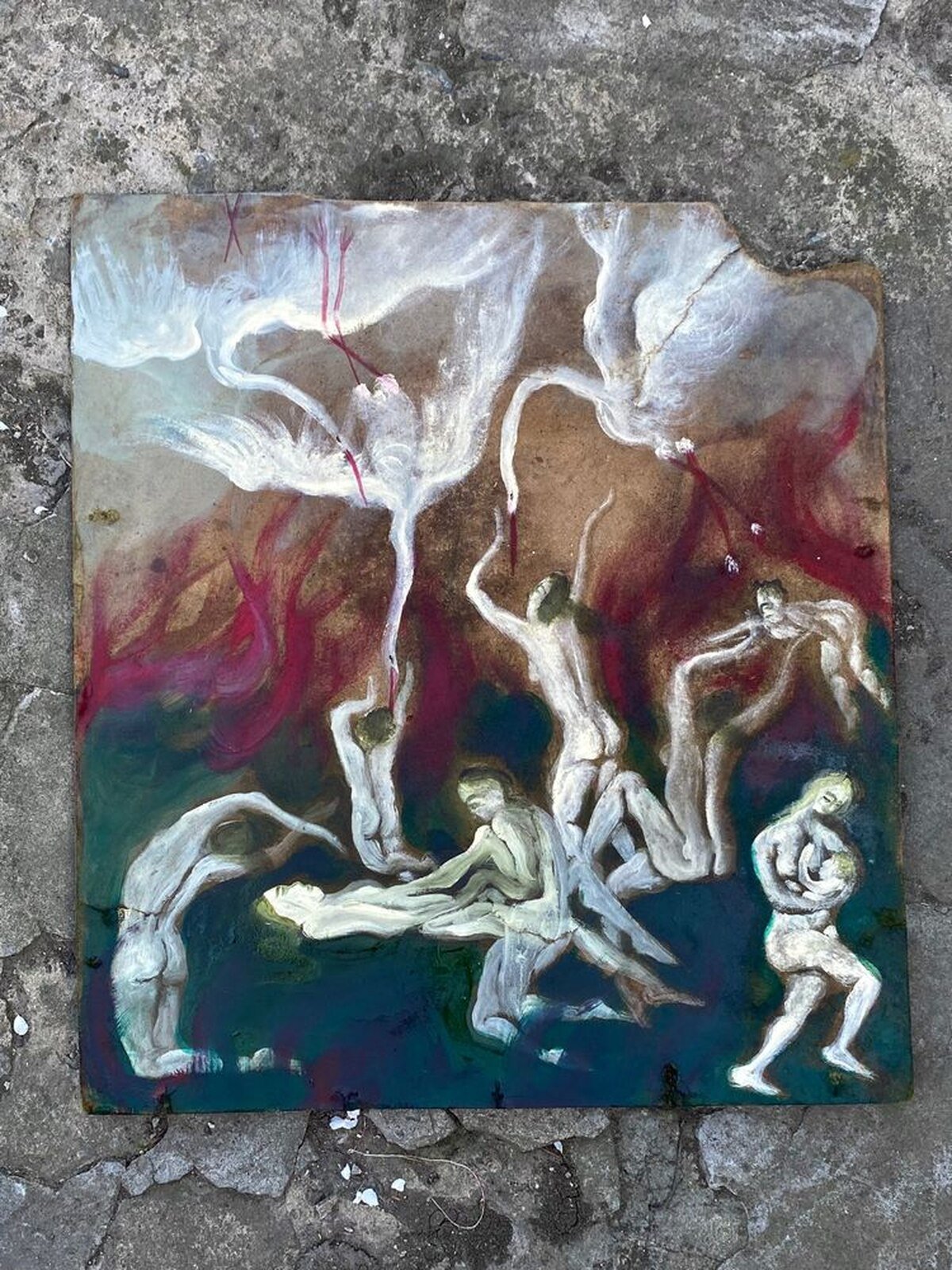

In light of the constant threat of destruction brought on by the full-scale war, the sense and understanding of the local have been transformed and interpreted by Ukrainians, including myself, in new and profound ways. For example, Odesa-born artist Sana Shahmuradova Tanska has been addressing the local through an interrogation of intergenerational trauma across the ongoing war. In her dream-like paintings, the artist depicts mythological inhabitants who translate both personal and collective memories of loss, grief, and violence. Shahmuradova Tanska delves deep into Ukrainian history and folklore traditions in an attempt to connect with ancestors and personal roots. While referring to the ongoing war, the artist reflects on the extended history of occupation, deportation, famine, and cultural oppression, looking for its echoes in modern times. Shahmuradova Tanska collapses the gap between past and present traumas, using her art as a tool for communication across and between generations.

Created in the first months of the full-scale invasion, Shahmuradova Tanska’s series War Diary (2022), demonstrates the sense of immediacy and raw response to war in both subject and medium. Shahmuradova Tanska used various unconventional materials such as scraps of wallpaper, tree bark, old cardboard, and clothing. In her work Mother Saving Her Children (2022), painted on three wooden panels, a female figure stands in the center with two children, one on her right and one on her left. Similarly, Evacuation (2022), painted on found wood, portrays people and animals seeking shelter together. Both works evoke Christian iconography that is often found in religious paintings: the wooden triptych recalls the image of Mary while the latter draws parallels to the story of Noah’s Ark and the narrative of the great flood.

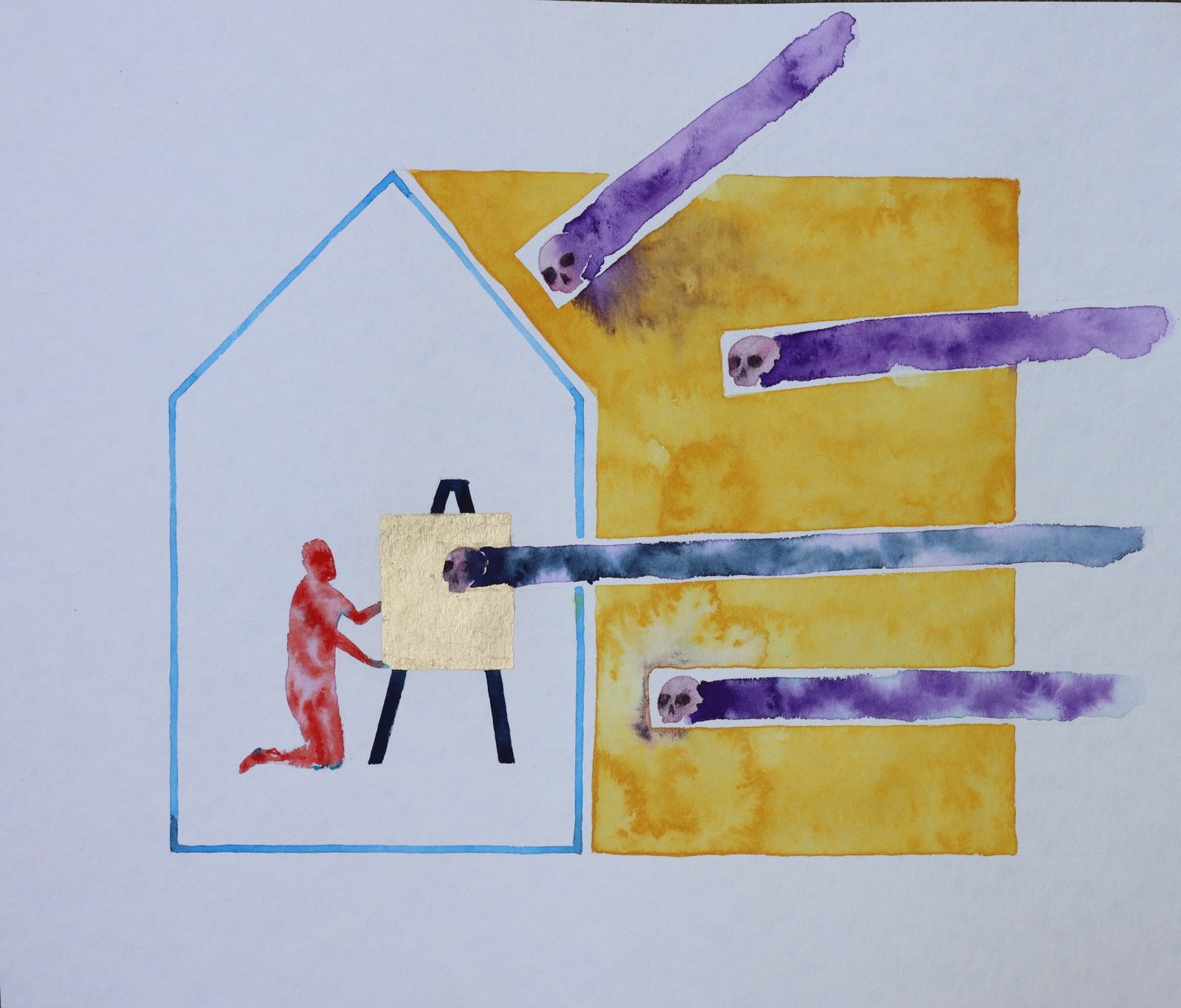

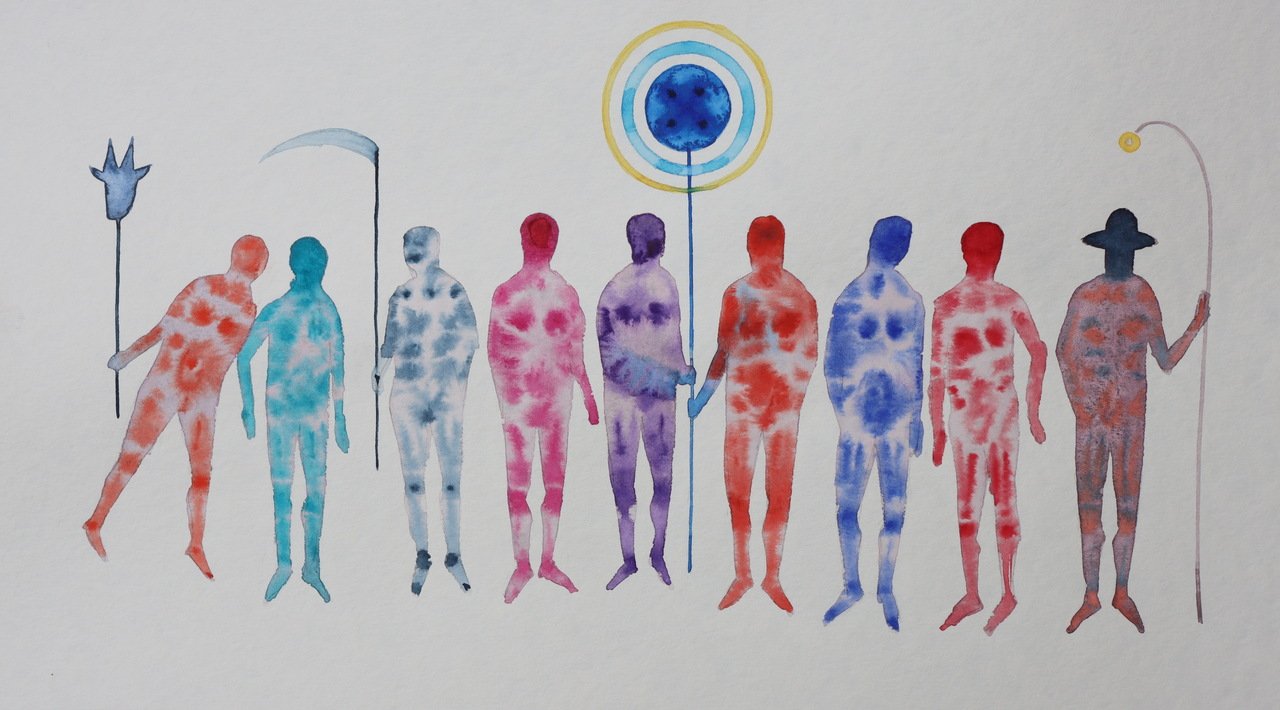

Close in spirit are the works of Lviv-born artist and iconographer Danylo Movchan. In his practice, Movchan deliberately seeks to create new Christian symbols through his distinctive style and visual language. In his artworks, he often explores existential questions such as the meaning or purpose of life, death, freedom, and identity, and their emotional manifestations. However, the ongoing war has shifted the focus of his practice. In the work Next to Easel (2023), Movchan reflects on the presence of war by depicting skulls bombarding a house. A human figure is on their knees, almost praying before a golden canvas. In another work, Samson and Lion (2024), Movchan revisits the recognizable narrative of Samson slaying the lion, which may be interpreted as a metaphor for Ukraine’s struggle against Russian aggression and its potential outcome.

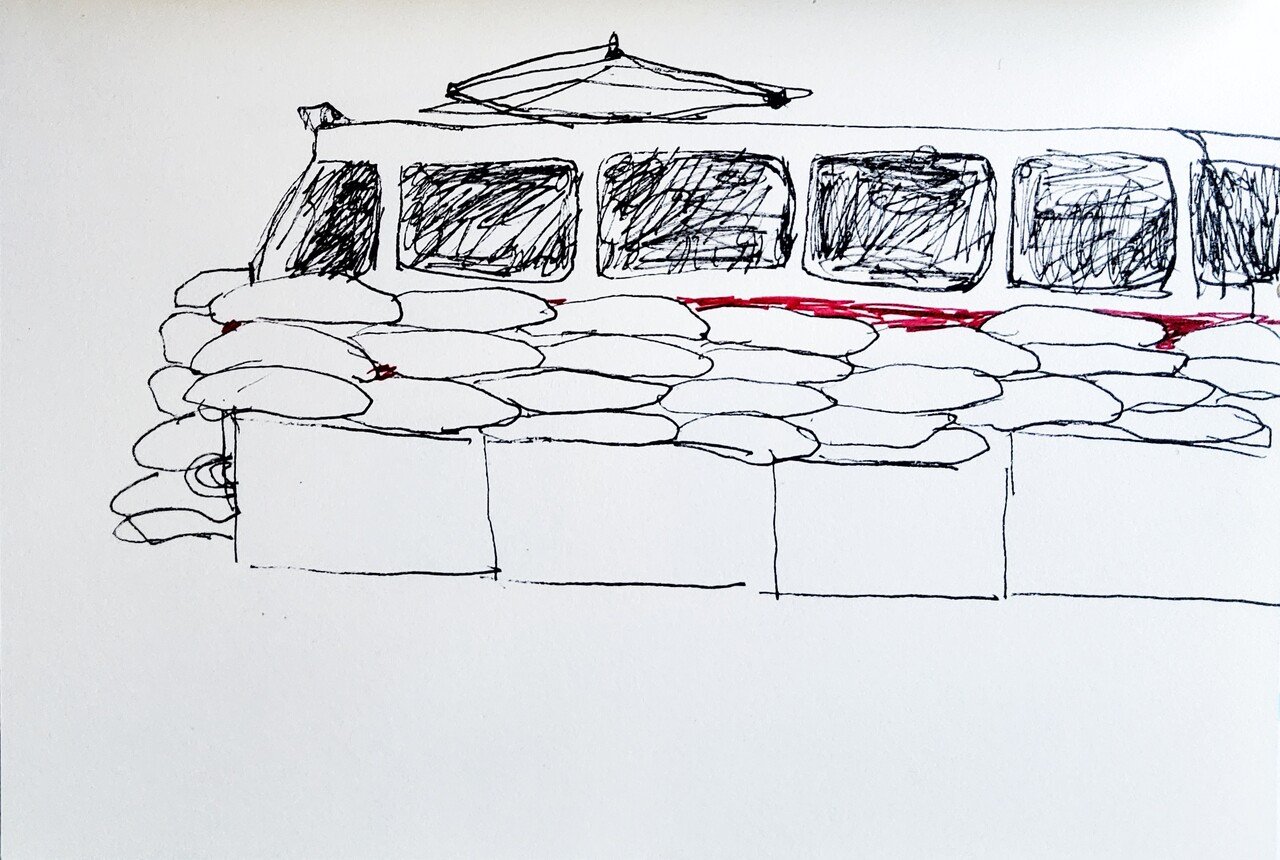

It seems that religious motifs in general have become more prominent in public spaces in Ukraine during the full-scale war, possibly serving as both a source of protection and inspiration. Lucy Ivanova, from Dnipro, does not directly engage with sacred elements but includes them rather as observations from her daily life. In her drawing Windows from Dnipro (2022), part of the 2022 War (2022) series, Ivanova depicts a fragment of a residential building where windows are adorned with religious icons. While the drawing does not replicate the icons in detail, the recognizable silhouettes of saints with halos, Mary with child, and the cross, evoke a shared understanding of these sacred images. For the artist, art is about the things that influence her personality and inner world, not existing outside of those roles, which she explores through different mediums. But of course, with the beginning of the full-scale war, everyday life changed and what was mundane began to take on new meaning. For example, the drawing Kyiv Tram (2022) reflects this transformation, depicting a tram surrounded by sandbags. In the paintings Hare near the block post (2022) and Hare running near military post (2022), she portrays hares in natural settings alongside military checkpoints. In Drinking Bear (2022), she refers to the occupied landscape of Crimea, depicting the summit of Ayu-Dag, which resembles a bear drinking water from the Black Sea. Ivanova paints the sea red and the landscape blue, symbolizing the ten-year occupation, subtly evoking the forces that have altered Crimea’s reality.

The local is further manifested in the appearance of animals and birds. For example, storks, in Ukrainian folklore, are often considered to be good omens symbolizing home and family protection, and are believed to save people from harm. These birds are a recurring motif in Shahmuradova Tanska’s work. One example is her commemorative work Bucha (2022), where she pays homage to the victims of the Bucha massacre. Painted on an old cloth, the piece depicts figures in visible state of horror. A red sun in the center of the work has tears streaming down, as if attempting to put out the fire raging on the earth, healing the wounds of those suffering. Central to the composition are storks, who are seemingly trying to help the people. Once again, Shahmuradova Tanska returns to such symbolism in her work Delay of Sowing (Posivna) Caused by Genocide (2022), where she depicts a woman with bread and a knife in the bakground of a wheat field. Next to the stork, the bread, representing unity and sharing, also serves a symbol of resistance, both in the historical and political contexts, evoking memories of the Holodomor – the artificial famine of 1932-33. This piece reflects the protection of the land and its people, particularly in light of Russia’s deliberate burning of wheat fields and bombing of grain repositories in Ukraine, today.

Similar symbolism also appears in Ivanova’s work Heritage (2022-2023). Through a silk vest inherited from her late grandfather, the artist explores collective experiences of war. Although her grandfather did not live to see the Russo-Ukrainian war, his experiences of World War II are embedded in this vest and now correlate with Ivanova’s current experiences of full-scale invasion as she embroiders the vest with beads in the formation of a war landscape: shelled Ukrainian land, rockets in the sky, burning buildings on the horizon, and phosphorus ammunition. She also includes a stork flying through the burning sky, a remnant of life before war. Although considering the symbolism of the stork, it can also represent hope and protection in this new time. Ivanova layers both tangible and intangible memories in the work, which serves as a carrier of not only her grandfather’s legacy, but combined with her embroidery, becomes a signifier of shared experiences of war, both today and historical.

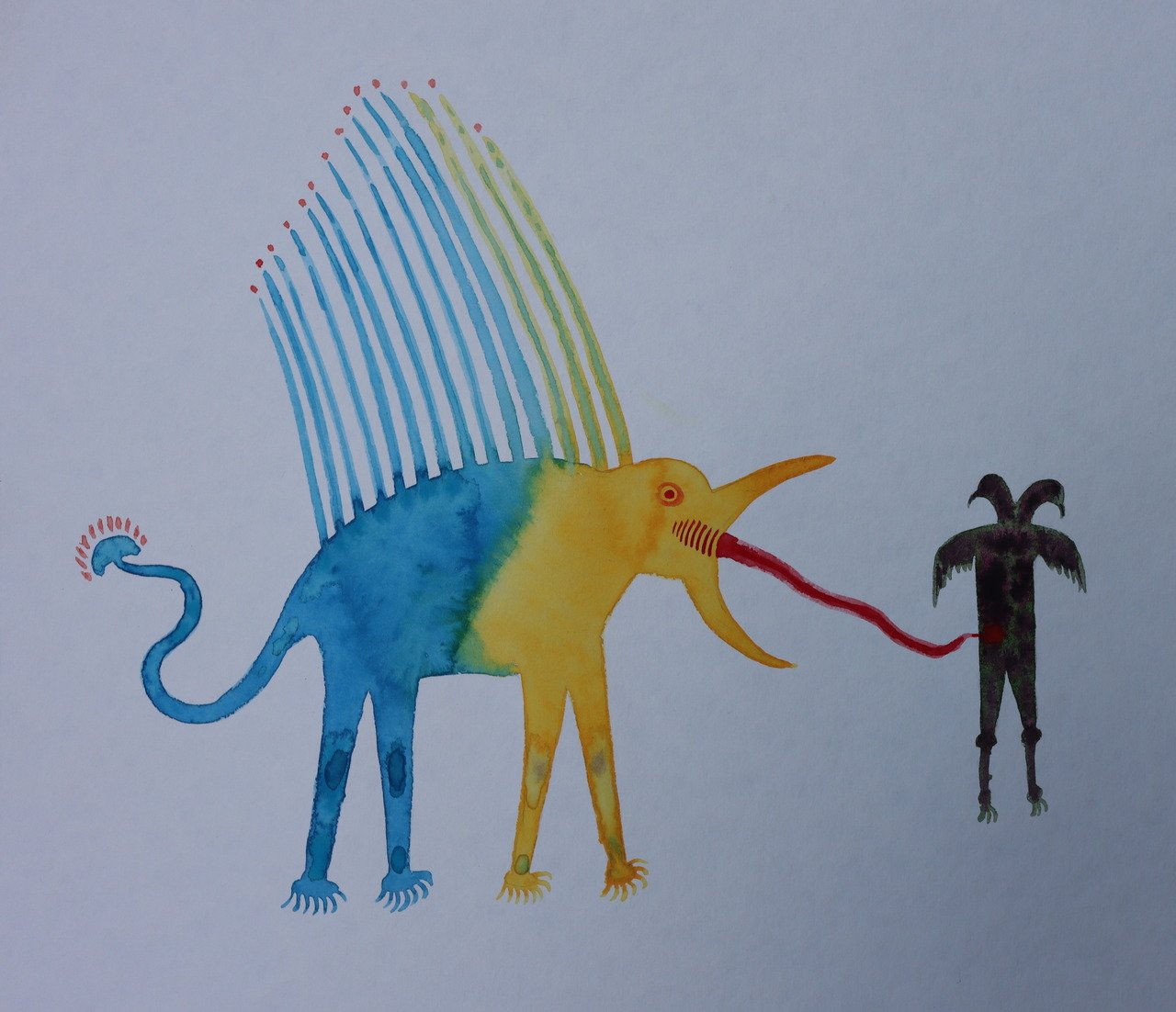

Similarly referring to animal mythology and iconography, Movhcan also addresses sacred and national narratives. In his work The Beast Attacks (2022), the artist depicts an unknown creature fighting against a clearly defined beast. The animal, however, strikingly resembles the magical beings from Maria Prymachenko’s vivid, fairy-tale-like world, which was often inspired by Ukrainian folk elements and stories.

In their wartime artistic practices, these four artists refer to particular localities, however, I will suggest that these localities do not merely confirm a present symbology, but become signifiers of wider epistemologies about Ukrainian (art) history and its context. These motifs are remnants of history: Shahmuradova Tanska’s work refers not only to the ongoing genocide of Ukrainian people but echoes a long-lasting experience of oppression, connecting the threads of violence that Ukrainian people have experienced from Russians across centuries. Ivanova and Movchan stress the social effects of this wartime reality by addressing localities of the sacred in the everyday. With her embroidery, Ivanova draws a clear line connecting that which is passed down from generation to generation. Local elements become remnants of the histories and traumas that have never left; they are signifiers the recurring experiences of pain and loss, oppression and aggression. Simultaneously, they allow for the contemplation and resurfacing of an uncomfortable heritage, both in collective and individual settings. It is especially in Kadan’s work where one can see not only the resurrection of such memories but also their connection to the non-marginalized narrative. While the specific local Ukrainian elements might not be as vivid in Kadan’s work, the installation does engage with complex local stories from multiple localities, creating a cumulative and plural process of re-centering peripheral (art) historical narratives.

Referring to both factual and metaphorical narratives, these artists connect historical events with collective experiences of lived war, displacement, hunger, and resistance. Not only as a manifestation of today and the recent past, but perhaps also as a warning for the future, so that history does not repeat itself. Even though expressed through local motifs, correlated with temporally and spatially-specific anxieties of the current wartime reality, these artists sensitively connect to universal feelings while uncovering unknown (to the Western art historical cannon) elements of Ukrainian art and history. The localities become important as connection points that grant agency to the periphery to share knowledge and to tell one’s story from one’s own voice, challenging the existing epistemologies and allowing art to be a form of learning and exposure to ignorance, conflict, and misrepresentation.

Dasha Lohyvnova is an independent art historian and researcher based in the Netherlands. She is a recent graduate from the Heritage Studies at the University of Amsterdam, specializing in Curating Art & Cultures. Born and raised in Ukraine, Lohyvnova’s research interests lie in exploring artistic and curatorial practices in the so-called region of Eastern Europe, with a specific focus on Ukraine and Ukrainian contemporary art. Through her research and future curatorial work, Dasha aims to understand the correlation between current artistic practice and ongoing social transformations in post-Soviet spaces.

This text is one of four commissioned for Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow, a project implemented by Fundacja Ziemniaki i and Stroboskop Art Space (Warsaw) covering themes related to the production, dissemination, and evolution of contemporary Ukrainian art and culture during active wartime circumstances. Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow is supported by IZOLYATSIA foundation, Trans Europe Halles, and Malý Berlín, and is co-financed by the ZMINA: Rebuilding program, created with the support of the European Union under a dedicated call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced people and the Ukrainian Cultural and Creative Sectors.

[i] Piotr Piotrowski, “Toward a Horizontal Art History of the European Avant-Garde,” in Europe? Europe! The Avant-Garde, Modernism and the Fate of a Continent, ed. by Sascha Bru, Jan Baetens, Benedikt Hjartarson, Peter Nicholls, Tania Ørum and Hubert van den Berg (Berlin & New York: De Gruyter, 2009), 49-58.

[ii] As a personal observation of a Ukrainian living abroad for the past four years. By this, I mean work by both individual researchers (for example, Ukrainian art historian Oksana Semenik aka Ukrainian Art History @ X (ex-Twitter)) but also institutional and governmental initiatives implemented by the Ukrainian Institute or through platforms such as MOCA NGO, The Wartime Art Archive, etc.

[iii] Piotr Piotrowski, “How to Write a History of Central-East European Art?,” Third Text, Vol. 23, Issue 1 (January 2009): 7.

[iv] Piotrowski, “How to Write a History of Central-East European Art?,” 5-14.

[v] Piotrowski, “How to Write a History of Central-East European Art?,” 7.

[vi] Svitlana Biedarieva, “Introduction,” in Contemporary Ukrainian and Baltic Art. Political and Social Perspectives, 1991-2021, ed. by Svitlana Biedarieva (Stuttgart: ibidem Press, 2021), 8.