Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew, Agnieszka Rayzacher

The protagonists of the exhibition Giantesses, despite using diverse media – from painting, through large-scale sculpture, photography, and video, to performance and ephemeral interventions – have much in common. First and foremost, they all have ties with Lower Silesia – whether a childhood spent here, a degree or academic work here, the choice of the region as the backdrop to their visionary projects or artistic practices, or the creation of a home for their community here. The title of the exhibition is a reference to a rock formation in the Ślęża massif – a mountain important to Lower Silesia in view of its location, the beauty of the landscape, and its history, which reaches back to pre-Slavic times, when it was a site of spiritual practices and sun worship. In mythologies, above all Norse mythology, giantesses are mighty women noted for their knowledge, strength, physical qualities, and spiritual beauty.

All the artists whose work is shown in the exhibition are active in the cause of others in parallel to developing their own practices, and striving to create new cultural environments is a leitmotif in all their biographies. Each one of them has at some stage in her life been engaged in collective work; the creation of art places, new circles, and communities; and caring for others. We focus on those aspects of their artistic life and values that involve closeness to people, places, and other creatures, and on the relationships between art and spiritual practices.

In its narrative layer, through its title and the reference to mythology, culture, geography, and the landscape – the Giantess rocks and the Giant Mountains themselves, the highest chain in the Sudeten Mountains – the exhibition draws in Lower Silesia, including Wrocław, but above all its mountainous regions. It is the mountains, with their energy, beauty, unique climate, but also the cultural richness and social relations that prevail there, that have attracted artists to the region for so many years: communes and art centers have been founded here, but it has also been a place of solitude, as well as spiritual and physical regeneration through contact with nature. The narrative layer is not only about Lower Silesia, however. Our protagonists have spent years in various regions of Poland, and continue to travel around Poland; for many of them, being on the road is a central facet of their identity, and one that recurs frequently in their art.

Giantesses is a narrative exhibition that meanders like a hiking trail, along which we can explore at close hand the work of these artists and places important to them. The first room showcases collective projects and initiatives in which they were involved at various stages of their lives. The following spaces are devoted to their individual practices, revealing the panoramas of their interests and their consistency in building up artistic languages. Each room is organized around a different shape connected with their art and biographies: a triangle, a rock, a bar, a net, and a table. Some of these objects serve functional purposes.

The influence of strong personalities on art is nothing new, and history is made up of the lives of such individuals who have made their mark on the vicissitudes of culture. In the exhibition Giantesses, however, we take a slightly different perspective, which is defined in contemporary culture as “weak resistance,” i.e. a turn away from the heroic model of subjectivity and toward activeness in the realm of affective and reproductive work. These five artists are linked by their biographies; they have all had ties to Lower Silesia at various stages of their lives. Their herstories constitute interesting research material, and show how different the contemporary narrative on life and creativity is when it shies away from being “outstanding” to focus instead on action, though without abandoning self-reflection. It is above all a tangle of threads – everyday life, creativity, and work in the cause of different communities. What our protagonists have in common seems to be agency. This has taken a range of forms at different stages of their lives, but has always involved a buzz of busyness, caring, organization on several levels at once, and constant building or renovating. The exhibition Giantesses offers an opportunity to look closely at the life and artistic practices of these exceptional individuals, and at the network of semantic and physical tubers binding together these very different personalities. Each of them knows or knew at least one of the other participants in the exhibition, and thus in addition to the map of the geographical points of importance to our artists, we also have the imagined map of their interpersonal connections.

Bożenna Biskupska

In her early work in the mid-1970s, Bożenna Biskupska concentrated on vibrant color, in painting and on fabric. She gradually shifted into increasingly severe spatial forms, in the early 1980s moving into large-scale sculpture, and over the years, the figures from her paintings also took on this third dimension. Both this personification and Biskupska’s observation of her own works come up frequently whenever she talks about them. They are primarily sculptures inspired by the human figure, though

far removed from any literality. Often appearing in groups, and made from concrete or natural materials – wood shavings, tow, sisal, metal, or wood – they have become repeating signs or individual freestanding forms. Biskupska works in cycles, some shorter, others extended and recurring like a leitmotif. Foremost among them is The One-legged Man (Jednonogi), a trope which has dominated Biskupska’s artistic imaginary for several decades. This unreal figure, standing on one leg, has taken the form of huge, usually concrete statues, but also smaller, even quite diminutive figurines cast in bronze. The repetitive character of this motif, the almost obsessive creation of more and yet more of them, is, the artist says, part of her message: “This dogged repetitiveness of mine in these figures is how I hope to help people realize that every one of us matters, even though there are eight billion of us on earth.”

In Giantesses, we juxtapose some of Biskupska’s expressive paintings from the 1980s with her sculptures – static, seated figures, and the contemporary wanderer: The One-legged Man. The whole is encapsulated in the geometry of a black triangle. Among the paintings is The Old Woman (Babka), one of only a few of Biskupska’s paintings with a narrative. This story is connected with the eponymous subject of the work: the elderly woman resident in the house purchased by the Biskupski family in the Brodnica Lakeland – even after the house changed hands. “The old woman was like a tree: almost invisible, but always present,” the artist recalls.

Katarzyna Rotkiewicz-Szumska

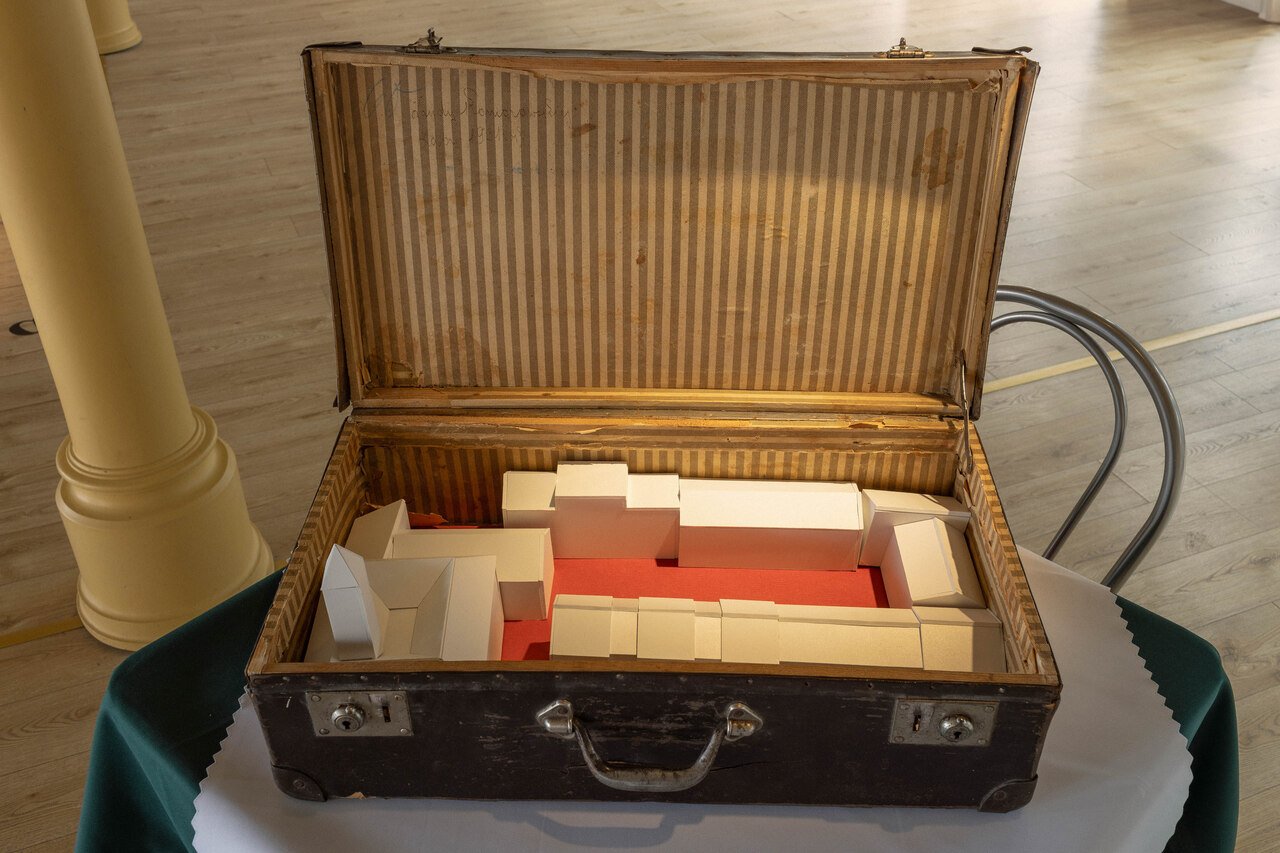

At the beginning of her career, after graduating from the De- partment of Painting and Printmaking at the State Institute of Visual Arts in Gdańsk, Katarzyna Rotkiewicz focused on non-representational painting. In time, particularly after she moved to the Giant Mountains in Lower Silesia, synthetic, sweepingly painted landscapes began to emerge from these abstract forms. As we move from room to room in her house in Michałowice, we repeatedly have the impression that these huge canvases are like windows, even though what they depict is by no means literal. In around 2010, after a hiatus of many years, when she devoted herself to theater work, Rotkiewicz-Szumska returned to painting. Her experience in acting and work with the body prompted her to leave her earlier landscapes behind in favour of faces and portraits. This gave rise to Gallery of Silesian Repatriates (Poczet repatriantów śląskich), a collective portrait of the Michałowice community in which she adopts various of the many media she uses – painting, photography, film, and even the spoken word – to honor her neighbours, people who, like her, are incomers to Michałowice, bringing their manifold histories with them.

It is virtually impossible to discuss Rotkiewicz-Szumska’s work in isolation from her house itself, which is filled with objects from her collections and items from the many theater set designs she has created. This is the reason why the exhibition also includes collector’s items from all over the world and from a range of registers. This symbolic house is rounded off by a panorama composed of large-scale canvases painted by her in the late 1980s, which together form an imagined mountain landscape. Against this background we see portraits and faces from several of her cycles of painting – portraits of her Michałowice neighbors, people of the theater she has met over the years, media celebrities, historical figures, and even death masks. “Inscribed into the map of our face is the path of our individual life, but also the paths taken by our ancestors. There is also a certain transgression – our future. The thread that binds all my works together and gives me no peace is the thread of passing. I was never able to go in a single direction. Balancing on the cusp comprises the hope of a liberation, of overcoming oneself,” the artist says.

Ewa Zarzycka

Ewa Zarzycka makes performance, photographic, and video art, audio pieces, and written drawings. She started out with photography, which she studied at the Wrocław Institute of Fine Arts under Andrzej Lachowicz. In the 1980s she made some works on film, and after a long hiatus, in around 2008 she returned to work behind the camera (this time the video camera), making mostly filmed performance works connected with her speaking appearances, her most typical form of creative statement. In these performances, Zarzycka shares her thoughts and tells stories based on a long-running plot which has for years featured a palette of real and imaginary characters: the Earth Sciences Professor Husband, the Postman, the Porter Lady, the Playwright Lady Next Door, Mr Philosopher Next Door, and the Kiosk Lady. Her work is a running record of reality incorporating elements of fiction and reflections on her own practice, being an artist, and the pressure to be constantly confrontational and build her “artistic position.” Her works combine a self-deprecating irony, humour, and distance with processuality, a characteristic open-endedness and ephemerality, and even lack of materiality. Zarzycka often contests her own art, subversively claiming that she has no “body of work.”

The main material she uses in her creative output is memory and personal experience, and she is constantly returning to and reinterpreting the past. In this exhibition she returns to Wrocław railway station as she remembers it in the 1970s, when it boasted a cinema, a hairdressing salon, and above all the station bar, which is recreated here. Displayed on the little tables are drawings by Zarzycka (which we strongly recommend reading) and her Zielona Góra Shorts (Filmiki zielonogórskie)—short, humorous video performance pieces that serve as a kind of artistic identity statement. Another important facet of the exhibition is her little-known Wrocław photographs, made during her time as a student in the Studio of Visual Activities and Structures under Andrzej Lachowicz. Zarzycka photographed Wrocław’s streets and tram networks, but above all she made images of herself and her friends. As such, many of them are performative in character, and their collective aspect is a harbinger of her film Signs (Przejawy) made a few years later. We also display some of her most recent works on the theme of travel, which she had been planning for several years.

Ewa Ciepielewska

Ewa Ciepielewska comes from Szczawno-Zdrój near Wałbrzych. She studied painting in Wrocław, where in 1982, she, Paweł Jarodzki, Bożena Grzyb-Jarodzka, and a number of other students from Konrad Jarodzki’s studio founded the legendary group LUXUS. This collaboration, joint creation, and in time also activism became as important to her as her individual artistic path, and the two became closely intertwined. In recent years, Ciepielewska has devoted most of her time to ecological work, in particular hydro-feminist activism. She is particularly passionate about rivers, which are the subject of her work on the project Flow/Przepływ. This is a type of residency on rivers, established to inspire more artists to do creative work in direct contact with water and nature. It usually takes place somewhere on the Vistula, which since 2016 has been the setting for informal joint performative plein-air rafting events lasting weeks at a time.

In this exhibition we show paintings on canvas and paper from all periods of Ciepielewska’s artistic career. The earliest ones, made when she was still a member of Wrocław’s counter-culture community, are imbued with a vibrant energy and alive with hallucinatory colors, reflecting the hunger for spirituality that consumed her in that period. They emanate esotericism, witchery, and the desire for a life in harmony with nature, and feature motifs popular at the time among people with a penchant for New Age ideas. For Ciepielewska this was not merely a youthful fascination, however; she still practices Buddhism, Taoism, and other forms of self-improvement. Many consider her a shamanic figure, but above all she is simply active in the cause of preserving biodiversity on Earth. All this is present in her work, whether in her paintings inspired by the landscapes she observes during her meanderings along the Vistula on the scow or in her portraits of her spiritual gurus. Animals are another major trope in her work, particularly the animals of the Chinese zodiac. The animals in this twelve-year astrological cycle feature in the calendar she paints every year: the Rat, the Ox, the Tiger, the Rabbit, the Dragon, the Snake, the Horse, the Goat, the Monkey, the Rooster, the Dog, and the Pig. In these works, Ciepielewska fuses inspirations from Oriental art with her own boundless invention and imagination.

Urszula Broll

This legendary Polish artist died in 2020 at the age of almost 90. She lived and worked for a long time in Katowice, where she was one of the members of the Oneiron Circle, and prior to that, while still a student in the Department of Printmaking in Katowice, the experimental avant-garde group St-53. In their studio at 1 Piastowska Street in Katowice, Broll, along with Henryk Waniek, Andrzej Urbanowicz and others, organized seminars and meetings. They also studied eastern and western spiritualities there, had all-consuming discussions, and delved into the first translations of Jung and Buddhist literature. In the early 1960s, these studies and interests moved Broll to begin creating geometric works in muted colours, which in time came to bear increasing resemblance to Buddhist mandalas, without ever actually taking on this form. Broll said: “I have a very profound relationship with my own works; I essentially make them for myself, to discover what I don’t know about myself… In silence, in peace, in communion with a mandala and my own experience, I find mental balance.” In the early 1980s, the artist followed her Buddhist community to the Lower Silesian village of Przesieka. She remained there almost to the end of her life, painting, meditating, a member of the Buddhist group, but also active in the local art community.

The works by Urszula Broll exhibited here form a relatively cohesive collection, despite having been created over several decades. Most striking among them are the geometric watercolours (a separate group betrays her fascination with the oeuvre of the German painter Paul Klee) and two oil paintings connected with her spiritual practice. The intricately detailed pen-and-ink drawings also call to mind Far Eastern art. On the one hand they include references to Buddhist iconography, but on the other they are also clearly inspired by views of the Giant Mountains that Broll loved so dearly; these were also an important subject of the watercolour mountain landscapes that she painted for many years.

On the table built in 1976 by Paweł Górski, a poet, painter and carpenter who was staying in the house at 1 Piastowska Street at the time, we have a display of books connected above all with Broll’s spiritual practice, selected by her son, Roger Urbanowicz.

Artist(s): Bożenna Biskupska, Urszula Broll, Ewa Ciepielewska, Katarzyna Rotkiewicz-Szumska, Ewa Zarzycka

Exhibition Title: Giantesses

Link: https://bwa.wroc.pl/

Venue: BWA Wrocław Główny

Place (Country/Location): Wrocław, Poland

Dates: 10.05—08.09.2024

Curated by: Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew, Agnieszka Rayzacher

Exhibition scenography: Jagoda Dobecka

Graphic design: Karolina Pietrzyk, Tobias Wenig

Photos by: All images courtesy of BWA Wrocław.