Cabaret Voltaire’s Vaulted Cellar offers a glimpse into the cosmos of Lee Scratch Perry (1936–2021). Many know him as “The Mighty Upsetter”. He is considered a reggae pioneer, legendary dub producer and once claimed, “I gave reggae to Bob Marley.” His influence extends far beyond the boundaries of reggae music and has inspired greats from various musical genres such as the Beastie Boys, Keith Richards and the artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. His dub productions have had a significant impact on various genres, including hip-hop, club music, experimental sound culture, dance-hall, and post-punk. Perry’s music is characterised by the use of echo effects, experimental samples, and loops that create a ritualistic atmosphere and captivate with powerful beats. His album “Jamaican E.T.” won a Grammy in 2003. However, Perry’s work extends beyond music and encompasses various forms of visual expression, including paintings, videos, costumes, totemic sculptures, and assemblages. These works incorporate found objects from everyday life, as well as religious, political, and pop-cultural imagery. Cabaret Voltaire’s main focus is the visual arts, which he has developed into a language of its own since the 1970s. His visual estate is now administered by The Visual Estate of Lee Scratch Perry on behalf of his widow Mireille Perry.

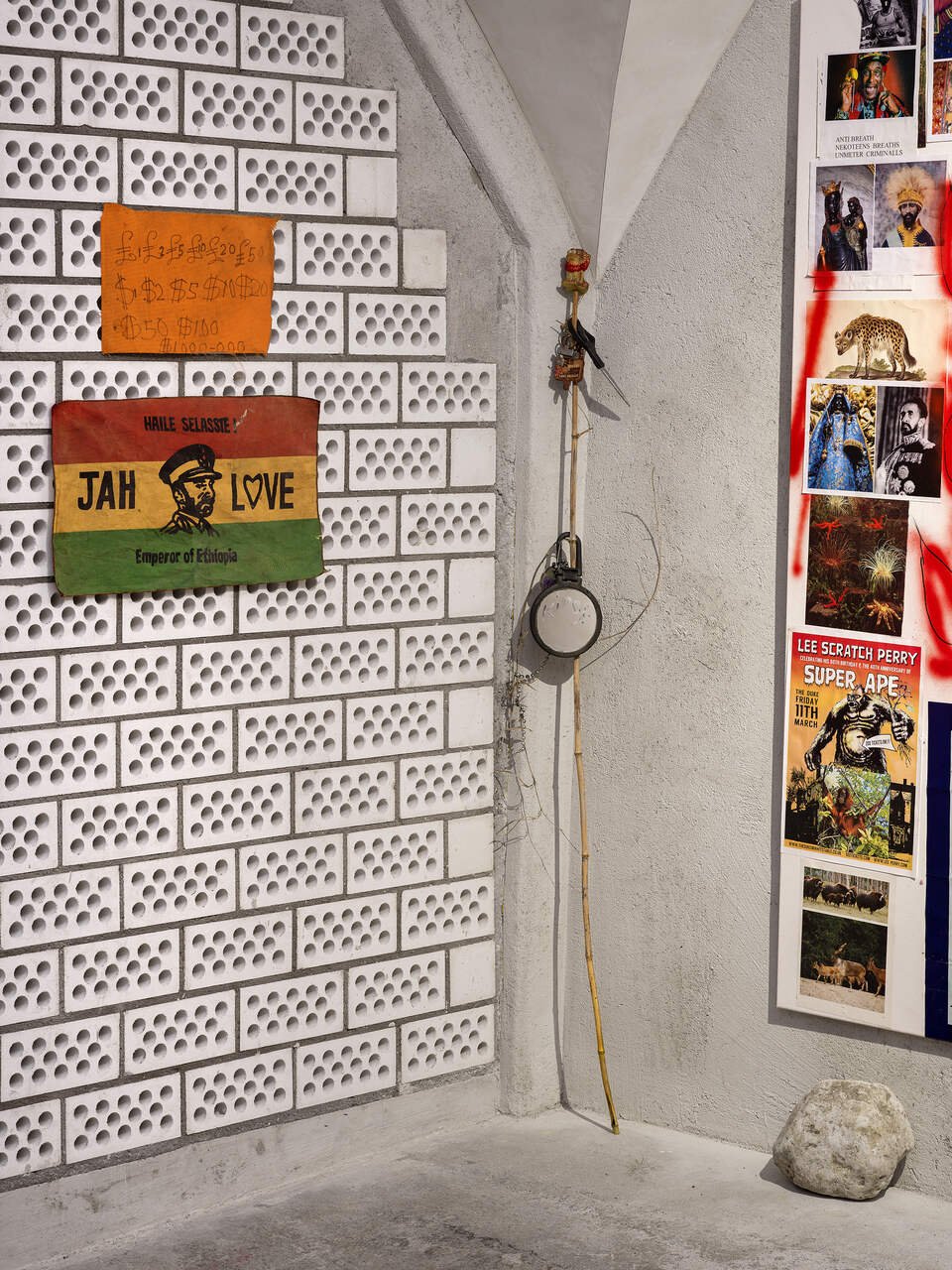

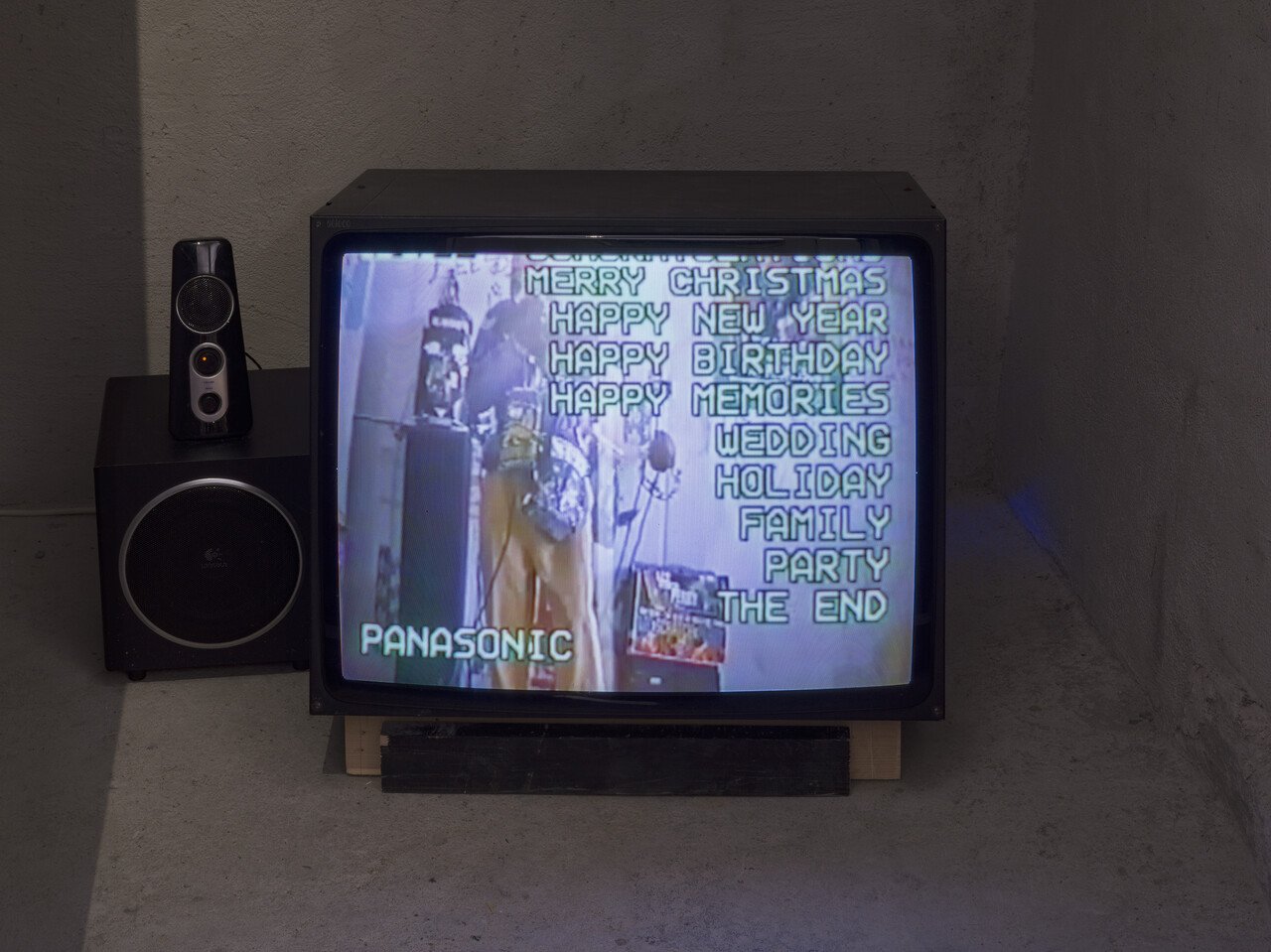

The exhibition is the first comprehensive institutional showcase in Europe and mainly features works from Lee Scratch Perry’s “Blue Ark” studio in Einsiedeln, Schwyz since the 1990s. The exhibition features works and studio elements that were obtained directly from the family home, making them accessible to art history. Notably, the large radiator, the “castle wall”, and the studio door remained installed in the family home until just two weeks prior to the exhibition’s opening. Perry’s studio was a place of ongoing artistic production. Not only was he a producer in his music, but also in his art. The magician organised gatherings, commissioned the decoration of his studio, and collaborated with artists who had their own artistic practice, such as Peter Harris or Maria Rodski. Those collaborations are also represented in the exhibition, with Rodski in Cherries (Blue Ark) and Peter Harris with a selection of drawings from the Higher Powers Bible series and a painting. Assistants such as Sebastian Roldan were also often present. Another exchange took place between Invernomuto and Perry in the film Negus (2016), in which Perry performs a fire ritual. Previously unseen video material was also edited for the show for the first time. Perry recorded and documented his life and practice using various devices such as his smartphone, iPad, MiniDV or VHS camera. The resulting recordings serve as a documentation of his experiences and the changing environment. They take on the character of works themselves, oscillating between poetic snippets and longue durée recordings. They provide a unique insight into Lee Scratch Perry’s studio, bring us close to his work and allow us to immerse ourselves in his world.

The exhibition, curated by Salome Hohl from Cabaret Voltaire in collaboration with Lorenzo Bernet and Valentina Ehnimb from The Visual Estate of Lee Scratch Perry, aims to capture Perry’s creative space. The presentation in the museum should preserve the magic of Lee Scratch Perry, however, without direct imitation of his art and with respect for the intimacy of his work. This task is challenging because the artist is only present through their works. Nevertheless, his wishes have been taken into account, such as the use of stones from the surrounding waters, placed according to his affective output process.

Lee Scratch Perry spent over thirty years of his life in Switzerland, despite his close links to Jamaica. He was born Rainford Hugh Perry in 1936 in Kendal, a remote Jamaican village. In 1961, he moved to Kingston to pursue a career in music, inspired by a divine voice. He made history with his famous “Black Ark Studio” and produced hits for Bob Marley & The Wailers and many more. When asked about his life in Switzerland, Perry once replied to the Guardian: “I enjoy living in Switzerland. I’m addicted to trees, ice, snow, rocks and all dem things. And there are way more than in Jamaica. I’m part elf. It’s too warm for me sometimes, I need somewhere cold. I love elves! Although you won’t reach a high shelf.” Perry’s move to Switzerland was motivated not only by his fascination with nature or his identification as a magician, alien or mythical creature, which is a recurring theme in his work, but also by love. In 1991, he and Mireille Rüegg, a former dominatrix and reggae enthusiast, were married in a Krishna ceremony. The couple initially lived with their family in Erlenbach on Lake Zurich and later in Einsiedeln in the canton of Schwyz.

Both Jamaica and Switzerland have had a significant influence on Perry’s work. An excellent illustration of this is his 2020 piece Untitled where he collages “Fishes of Switzerland” alongside the Einsiedeln Black Madonna and Haile Selassie, the last emperor of Ethiopia. Perry superimposes the image of grace of Einsiedeln, which is popular with the Black diaspora, with the “King of Kings” and “Lion of Judah”. Selassie is revered in the Rastafarian movement as the return of Jesus Christ, often referred to as “Jah” or “Jah Rastafari”. His coronation in 1930 was seen by many Rastafarians as the fulfilment of biblical prophecy. He is revered not only as a political leader, but also as a spiritual symbol of liberation and the restoration of African identity. His fight against colonialism and racism has made him a central figure for the Rastafari. The movement identifies non-colonised Ethiopia as its “Zion” and rejects the Western “Babylon” system, while cannabis use is part of its spiritual rite. Selassie often appears in Perry’s art as a portrait, “Jah” or lion.

Selassie was a member of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, a Christian denomination closely linked to the Coptic Church. Perry also repeatedly features Orthodox saints, such as St. Nicholas of Myra. The Rastafarian movement has a distinct religious identity that combines elements of Christianity with African spirituality and political philosophy. Perry’s universe exhibits syncretism, with concrete political references in works like I.M.F. Perry Attack (2020) (where I.M.F. stands for International Monetary Fund) and utopian or post-apocalyptic worldviews in works like the image of the ark or the poster “I Am America”, which depicts a post-Flood world map. In Perry’s work, however, an “Upsetter moment” always remains legible. This is likely due to his encounters in London during the punk movement, which expanded his artistic and fashion vocabulary and which he found liberating.

Lee Scratch Perry, along with Sun Ra and George Clinton, is considered a pioneer of Afrofuturism due to his exploration of visions of the future from an African and African-diasporic perspective. This movement responds to the underrepresented or stereotyped representation of black people as radical empowerment and explores themes such as identity, technology, power structures and social justice. Futuristic elements are often recognisable. In Perry’s case, this is also evident in his interest in technology and his departure from traditional dress and behaviour. The importance of superheroes in his work can also be discussed in relation to Afrofuturism. They can be found everywhere, including positive re-appropriations such as “Super Ape”, which also served as the album title. References to Egypt are also frequently present in Afrofuturism, as in Perry’s work. Egypt symbolises the historical and spiritual centre of African culture and identity, as well as proof of the abilities and achievements of African peoples before European colonisation. It also serves as a foil for their own projections of the future.

Afrofuturism is one reason why Perry remains relevant today, alongside his otherworldly creativity, creative power, and world design. Equally important are his techniques in music and art, such as his typical method of overlaying and sampling. The term “Dub” originates from the word “to double” and refers to the process of duplicating sound carriers. This technique is also used in visual art, such as collages and assemblages, as well as in the repetition and cross-fading of sentences and image motifs. Through the combination of different disciplines and a close network of references, allusions, quotations, and contextual links, the work can also be seen as a Gesamtkunstwerk. Both the creation of a comprehensive aesthetic experience in various disciplines and media, as well as the sampling technique, including collage, and the processual and collaborative do-it-yourself technique bring Perry close to the history of the house. The Cabaret Voltaire is the birthplace of Dada, and the Dadaists are credited with declaring found objects to be art, breaking with social norms, merging words and images, and creating their own mythology. In both cases, art is not separated from life and creates an overall context that connects mutually exclusive opposites. This was the case with Dada, which combined spirituality and everyday politics, as well as the particular and the universal. The same can be said of Perry. As his biographer David Katz wrote, Perry was a bundle of contradictions: a Rastafarian who believed in extraterrestrials, argued in favour of black supremacy while living in Switzerland with his European wife. He is among the few creative forces who undoubtedly deserve the title of a legend. Michael Veal once wrote about Perry, stating that he was capable of transporting people into Nirvana and into vast realms of cultural and political imagination: whether to Africa, (or to Switzerland), to outer space, into the inner space of thoughts, into nature, or towards political and economic liberation. Thank you, King Lee Scratch Perry.

Lee Scratch Perry, “Thank You Great God”, undated; Lee Scratch Perry and Peter Harris, “I Am Sory, from Higher Powers Bible: From Genesis to Revelation series”, 2014–2015; Lee Scratch Perry and Peter Harris, “Jus Stick Jus Shit”, from “Higher Powers Bible: From Genesis to Revelation series”, 2014–2015; Lee Scratch Perry and Peter Harris, “God Good”, from “Higher Powers Bible: From Genesis to Revelation series”, 2014–2015; Lee Scratch Perry and Peter Harris, “Revelation Blood Clouds, from Higher Powers Bible: From Genesis to Revelation series”, 2014–2015; Lee Scratch Perry, “I Wish to Stop Sinmokes”, 2020; Lee Scratch Perry and Peter Harris, “Sin-Akes, from Higher Powers Bible: From Genesis to Revelation series”, 2014–2015. Photo: Cedric Mussano.

Besides Lee Scratch Perry, the following individuals also contribute to the exhibition: Peter Harris, Invernomuto, David Katz, Lhaga Koondhor (House Of Intuitions) & Dave Marshal, Trinity Mesime Njume-Ebong (Mother Dubber), Sebastian Roldan, Maria Rodski, Volker Schaner, Scott Seine, and more.

Works by Lee Scratch Perry have been exhibited, among others, at the NMAAHC / Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC (2023), at the Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen in Düsseldorf (2023), at the MACRO – Museum für zeitgenössische Kunst in Rome (2022), and at the 34th São Paulo Biennial (2021).

Artists: Lee Scratch Perry, Peter Harris, Invernomuto, Maria Rodski

Exhibition Title: Lee Scratch Perry

Venue: Cabaret Voltaire

Place (Country/Location): Zurich, Switzerland

Dates: 12.04.2024–29.09.2024

Curated by: Salome Hohl, Visual Estate of Lee Scratch Perry (led by Lorenzo Bernet and Valentina Ehnimb).

Photos by: All images courtesy of Cabaret Voltaire, photos: Cedric Mussano. Courtesy Lee Scratch Perry: The Visual Estate of Lee Scratch Perry