Bartosz Zaskórski in conversation with Ewa Borysiewicz

Ewa Borysiewicz: First I wanted to ask how are doing and start our conversation with a question regarding your upcoming music release, first time as “Porosty”. Congratulations!

Bartosz Zaskórski: Thank you! I am now in an apartment in Krakow. I feel ok but I have a small cold. Yes, “Dungeon Crawler” will be published by Smashing Tape Records, a German label. [1]The music is a further exploration of my signature “rural dungeon synth musical aesthetics” as somebody once referred to it, but this is my first album with vocals. I wrote some of the lyrics myself, others were a collaborative effort with people like Artur Sobieraj and Violent Poison.

EB: Are the lyrics of the songs connected by some sort of a theme? Or mood?

BZ: They were written to reflect the moment, but there’s a recurring rural Polish thread that ties them together. In a way it is striking and intriguing for me how for Polish cultural workers (the ones from the capital at least), the Polish countryside – where I come from – is predominantly something strange and exotic. It almost resembles “the Zone” from Andrei Tarkovsky’s “Stalker” or “Area X” from Jeff Vandermeer’s “Annihilation”: a mysterious, dangerous place where the laws of reason and physics do not apply. And it’s still a very disheartening experience for me: despite the passage of time and many equalitarian concepts in circulation, I still meet with some dismay when I talk about me and my family coming from a small town. On the other hand – and although I am very tempted to do so, I don’t want to call it “peasant mania” – I observe a trend among friends coming from the “big city”, how they try to discover their village or rural roots for themselves, exoticizing them at the same time. Nevertheless, I am very attached to my small-town origins. And this is ever present in the lyrics I write.

EB: The very first track of “Dungeon Crawler” mentions a very important animal for you: “A dog is a dog is a dog, it feeds on carcassess, it roams (…), a pack of dogs was seen somewhere close, they’re coming, they’re coming, they’re coming.”[2] You like dogs very much, it’s hard not to notice that. They appear not only in your texts, but comics, paintings, drawings as well.

BZ: Right, they do come up often. The first text for “Dungeon Crawler”, appeared in my head very quickly and unexpectedly while I was working on “Psizm II”, an exhibition about dogs that I took part in.[3] As I mentioned, I’m from the countryside and my family has always embraced animals. At the moment there are five dogs and four cats at my parents’ house.

EB: What are the names of the dogs and cats?

BZ: Here we go: Lula[4], Mikusia, Figa, Pufa, and Beza. These are the dogs. With cats the matter is more complicated, because there is Niuniek, Gruszeńka, and Kociczka, but there is also Czarny Kot (Black Cat). For some reason, no name stuck to him for long, but Czarny Kot somehow captures his character. He is a very black cat: very laid back, talkative… I think it’s a good name after all. And together with my parents they live in the village of Żytno.

EB: What do your parents do?

BZ: My parents are teachers in a small elementary school in a village near Żytno. My mom teaches elementary education and music, my dad teaches art and computer science. I don’t want to say that they’re stuck in Żytno, because this implies that somewhere out there there’s a better world allowing a fuller life. Of course, the reality of the countryside does not make certain things easy or even possible, but the same goes for the reality of a town, a city, a metropolis. Not everyone’s dream is to move to a more urbanized place such as Warsaw. And still, for some people I meet – in the artworld and beyond – it’s incomprehensible to be born in a small village and to want to stay there. I once worked on a musical score for a theater play and when talking with one of my collaborators I was asked where I’m from. I answered that I’m from a village, and my parents still live there. And my interlocutor’s reaction was: “What? They were exiled there or something?”.

It seems to me that in Polish culture, classism remains an unprocessed issue. I mean, there are some projects that do tackle this subject, that aim to problematize the shame around one’s origins, but I rarely see works that encourage one to shed this shame, they rather normalize it. Of course, I am now generalizing, and probably if I took a deeper dive I would probably find such threads. I feel the discourse generated in and by the center – in my case, Warsaw – around these works, has a romanticizing, or exoticising aspect to it nevertheless. However, there’s an important change happening: drawing attention to previously repressed aspects of one’s origins, and pointing to very clear (financial, career, access) barriers related to them.

EB: I agree, the change is happening, but we’re not at the finish line yet. It’s a different thing of course, but I just thought of how adopting dogs is now very popular, which was not the case 2 years ago or so. You’re a well-known advocate for animal rights and animal adoption and I’d like to return for a moment to dogs: mutts and mongrels specifically.

BZ: Dogs, dogs, dogs… I feel that animals (cats and dogs specifically) have given me so much wisdom, acceptance, affection… I feel I need to reciprocate their kindness with the human tools available to me. Animals have always been somewhere close to me. I also needed time to learn to appreciate their presence. I’ve grown to develop a kind of empathy and understanding with animals. A turning point in my life was when, at the age of 23, I ended up in a psychiatric hospital. And when I came out of the hospital, it was extremely difficult for me to find a place in the human world. At the time I saw there was a very firm division between the world of “normal people” and those who had mental health problems. And I remember that the presence of animals helped me very, very much to recover and return to the world of the living.

Some time ago together with my current friend we adopted a mutt called Tofu from a shelter.[5] It was a dog of an elderly lady. When she passed away, the grandchildren left it in the shelter. The relationship with Tofu was a breakthrough. I began to think about the ways dogs or cats are treated by humans, that they are often reduced to a trendy gadget. In consequence, there is a demand for breeding dogs: there’s a lot of them, and shelters are overcrowded… This is completely unregulated in Poland by the way. There are pets that need a home, that need a human being. Whenever I have a chance I always remind my audience about the fact that if you want to have a pet in your life, it’s worth adopting a pet instead of buying one.[6]

EB: You were also volunteering at a shelter for a year and a half.

BZ: Yes, in the shelter I spent a lot of time observing how each dog has its own personality and with each one you can get along a little differently, you should use a different approach with each of them. And the character of the person who adopts is also crucial, and as volunteers we tried to match the dog’s temper with the personality of its future owner. Older dogs who don’t have much life left can also teach us a lot regarding our relationship to death, to help us accept it. Death just happens in their worlds. Sacrificing a small part of your personal human comfort by adopting an older dog, so they can spend the last part of their life in better conditions seems like a very sensible thing to do.

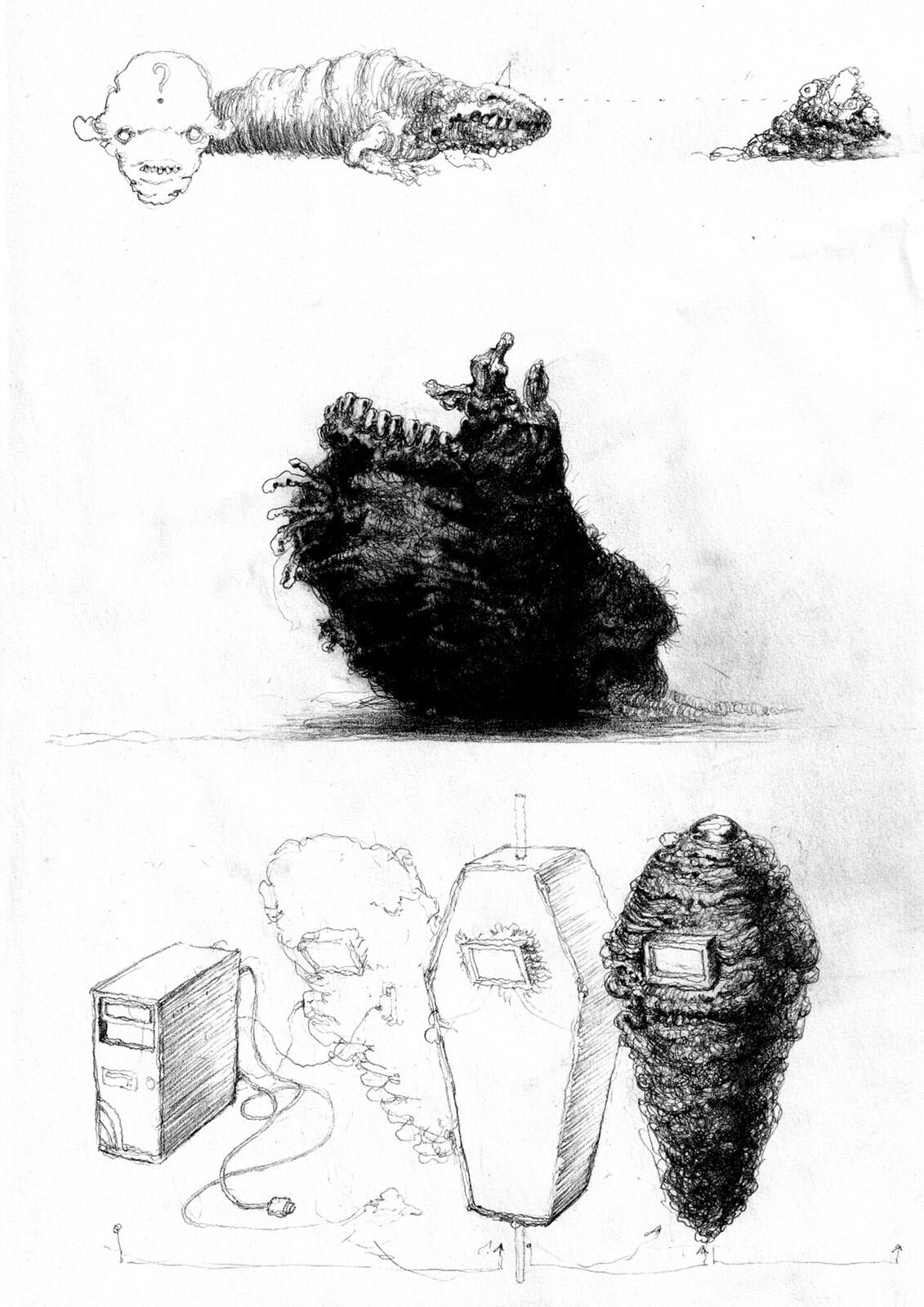

EB: Mutts appear in your comics, music, they are subjects of the exhibitions you curate… Other creatures that pop up throughout your work are mutants.

BZ: A mutt seems like a cool metaphor to me, because every mutt is a bit of a mutant: a creature from nowhere, with an undefined identity, built from many different elements. In fact, I feel a bit like a mutt-man of sorts, an odd-ball who doesn’t belong anywhere: neither to the world of visual arts, nor to the world of club music, nor to the world of classic graphic novels. All my life I felt that what I do artistically was balancing on the edge of different media, registers, and milieus. That’s why this figure of a mutt is taking a stronger root in me, and I’m sure I’ll be revisiting it.

EB: It’s precisely this incompatibility that you’re mentioning that I find very interesting: during your interview for Solo Show – a Polish YouTube channel on contemporary visual arts[7] – when the presenter, Tomek Szymański, introduced you to the audience as an “artist”, you corrected him, stating that you’re not. I wonder why you reacted so strongly. And if you – an author of music, paintings, and drawings – are not an artist, who is an artist in your private vocabulary? Also: do you have a definition of art for yourself, and if yes, could you tell me about it?

BZ: I’d say that I’m not sure who is and who is not an artist… And I don’t know when art begins and when it ends, either. But to be honest, I’m not entirely interested in this issue. It seems to me that a kind of modernist mythology of art is still alive, and it constantly influences us, providing us with certain ideas related to what art is, and when you are an artist, and when you are not. And consequently: what is outside this firmly outlined area is art no longer. In the beginning of the 20th century, the “heyday of manifestos” as it is often referred to in art history, this kind of need to radically separate art from non-art was indeed very important, but I feel it is no longer necessary. And the fact that I sometimes find myself saying this is due to the fact that I’m very close to pop culture and I don’t parenthesize it or parody it. Pop culture contains a whole lot of interesting content which often does not result from and does not directly involve references to theory applied in contemporary art practices.

But at the same time, pop culture often anticipates certain trends that, for example, are now prevalent in the space of art or philosophy. Take the many recent exhibitions themed around anthropocentrism: if you look at science fiction books or animation from the 1960s, 70s and 80s – like works by Philipp K. Dick or Ursula K. Le Guin – it’s very easy to spot these themes. Of course, they were never called that way back then, because this kind of conceptual grid did not yet exist. In pop culture they appear – I assume – intuitively and without mediation, but emerge decades ahead of certain trends in art. And it seems to me that pop culture is as vibrant and perceptive as contemporary art.

EB: I agree that the line between pop art and high art did not disappear, it just moved to a different place.

BZ: In the case of “high art”, in my understanding of it, it seems important to emphasize the notion of creating works aimed at a very specific audience that has accumulated the necessary cultural capital. What seems fantastic to me and where I see great potential is that pop culture – whether it’s video games or animation or films that are not considered arthouse – does not have a high threshold of entry (are easier to access in terms of costs, effort etc.), but at the same time, can be very saturated with content. An example of this is “Disco Elysium”, a video game by ZA/UM where the whole narrative relates to complex Marxist theories, which are introduced to the player with a high degree of meta-reflection. And a completely different example are games developed by FromSoftware, such as “Bloodborne,” where the authors have done some gigantic work researching various themes of Victorian culture, repressed sexuality included. Pop culture can reach a much wider audience and art on the other hand, constantly cultivates entrenchment in its own positions, preaching to the converted so to say, a situation where there’s an assumption that everyone agrees on certain things. And as a result a kind of inbreeding of ideas occurs…

EB: Again, we are back to the “mongrel metaphor”.

BZ: A bit. There is another aspect of this issue: the other type of viewer, besides the specialized, culturally competent one, are the very wealthy people, who often see art as a resource, an investment. And this is another of the many bizarre, perverse relationships that artists agree to, because they have no other choice. I feel much more comfortable – as opposed to openings or semi-social artworld situations – at a booth at a comic book fair, where people visit me to talk about graphic novels and music. It feels natural. That’s why the artworld appears to me as bizarre and foreign. But when I think of it, every “world” I’ve gone through has similar traits…

EB: We once talked about your various interactions within the art world. You didn’t have many good experiences, did you?

BZ: Right, but still, I try to focus on the many great experiences I had as well. For example, with the Zachęta Project Room in Warsaw. I was absolutely delighted to work with Magda Kardasz on my exhibition with my dad, “A Spaceship as Big as Half of the Village.”[8] I also have very fond memories from the Centre of Contemporary Art Kronika in Bytom.[9] What an awesome team! I’d say it’s just more orderly when it comes to institutions, perhaps because people working there have some peace of mind, a sense of stability that only an institution allows, like the benefits one has from having a full-time position and regular income.

EB: And how does your collaboration with Hollow Press[10], the publisher and distributor of your comics, compare to your experience with the artworld?

BZ: Well the story here is quite peculiar, because Hollow Press approached me on Instagram. They simply sent me a message saying “Hey, we like your drawings, do you have any comics? We’d like to publish them.” I at first reacted with distrust, thinking that it was some kind of scam, like those NFT pitches you sometimes receive… In any case, with Hollow Press, the cooperation has been absolutely great. First of all, I get money for the whole print run, so not from individual sales, but as soon as the whole run is printed I get the money for the whole thing. And whether it will sell or not is a risk that the publisher takes on, which motivates them to put major effort into promoting a title, to support their artists, and regularly invite them to various comic book festivals where they can meet their audience. This also seems to me to be a nice way to build some kind of relationship with people who buy and read my stuff. Besides, Hollow Press buys original comic boards from me and sells them on their website. And despite the fact that this publishing house has grown a lot since I started working with it – a whole bunch of new artists have joined their roster – I don’t feel neglected or left alone. I’m not put in the position of a supplicant, where I have to remind, inquire etc. It’s a fantastic cooperation and I’m very happy about how it’s progressing: the French edition of my comic is coming out soon and right now, there are talks about a Polish omnibus edition of the three comics I published with Hollow Press.

And it’s also worth noting here that this is a very small team of people, and in fact most things are managed by Michele Nitri – chapeau bas to him – the head of the publishing house. Working with Hollow Press made me think to what degree the treatment me or my friends accept from galleries or curators is toxic and at the same time, normalized. Of course, this is related to – let’s call it – power dynamics, in which the artist does not have any leverage, and the gallery does. Everyone complains about it, everyone is pissed off, but at the end of the day everyone accepts these dynamics, and the situation remains the same.

EB: But now the question is what would have to happen for this to start working differently and for the artist to be treated fairly?

BZ: I have no idea what the first steps should be. I should add that I don’t know what the Polish comic book market is like, because I haven’t had the opportunity to work with it: I can only compare it to my experience in the art world. I can only say that the comic book market in Italy is very developed, as evidenced by the existence of a publishing house that wants to publish underground, strange comics and is able to prosper and grow. But I also don’t want it to sound like I’m justifying various strange practices that I encountered during the ten years I’ve been functioning in the Polish art world.

I’m not saying that galleries should operate like a comic book publishing house, because I realize that this is a different environment. The price of a painting and the price of a comic book board are also two completely separate stories. It’s not about buying works from the creator, but about clearly defining the division of costs and responsibilities. What I mean is that the rules of cooperation between the artist and the gallery/publisher should be clear from the very beginning. And, above all, there should be a contract that determines all this. The artist should not have to ask themselves “what is my right and what is not”, because all this should be in an agreement where it can be looked up and verified. This is the fundamental difference. To my knowledge, the way things are now, we’re operating in an unclear, murky space, where rules are based on assumptions.

EB: I wanted to ask you about comics and your – I will call it artistic anyway – work in general. I admire your drawing skills and the way you control the line: it’s disciplined, and yet it seems free, having a life of its own. In your graphic short story “Atrocity Exhibition” from “Weird Tales of Postapoland”, taking place at an opening of sorts, the artistic establishment is also mutated, distorted. The only characters that can be identified are characters with whom you have a strong emotional bond, e.g. the artist Jagoda Czarnowska[11] or Tofu the dog. My first thought was that such a grotesque portrayal of the art world has a revengeful undertone. I wonder if my intuition is accurate.

BZ: I didn’t think about it that way, but I like your interpretation. If I ever create a video game where I will be able to influence both the visual and narrative design, I definitely want to include a similar situation there, a vernissage. At first it will be very stiff and supposedly nice but the “nice” will be laced with unintentional cruelty, imbalance, resulting in violence. Worse and worse things will start to happen, and a terrible cathartic massacre will ensue. That’s the idea for the moment. My point is that your intuition is relatable, and that the first drawing of this micro-story is actually about how I feel at an opening: completely out of place. I feel like a mutant and a freak myself, the rest reminds me of purebred dogs, beings without any blemish, perfect. On the one hand, it is a sophisticated, conventionalized world, but on the other it is alien and terrifying, some cosmic horror is revealed in people’s behavior, cruelty and narcissism. The artworks that you see seemare secondary to the personal gains.

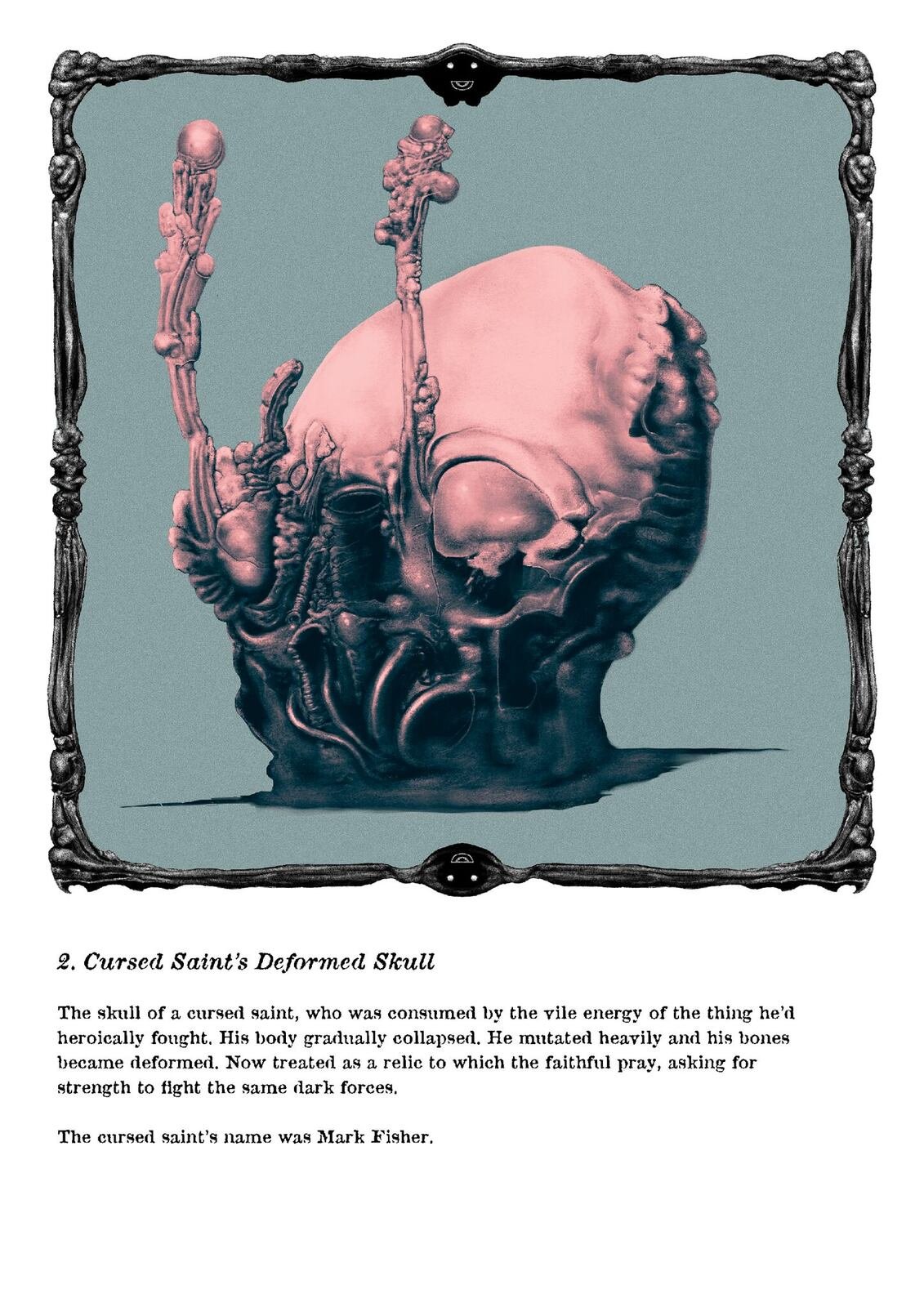

EB: The scene you drew reminds me of the prose of Thomas Ligotti, the author you introduced me to, known for combining horror, weird fiction and nihilistic philosophy. You mentioned “The Conspiracy Against the Human Race” and “Teatro Grotesco” as one of your major influences. Ligotti describes hopeless situations, feelings of being a prisoner of one’s circumstances, being drenched in misery. I am not sure if I can fully relate to such a worldview. I mean, we’re all aware that life has value, yet makes no sense and that we must create this meaning for ourselves… I’m curious what’s your take on this. To be precise: how do you cope with this misery, do you have ways of countering the existential despair and helplessness that Ligotti portrays in his novels?

BZ: Dogs, love, and dark humor. That’s all that stabilizes me in this world. It’s a simple recipe, but I think that’s how we’re built. As for Ligotti, to me what he describes is a shared experience of a very large part of humanity in – let’s say – a relatively safe or relatively affluent reality of the so-called “West”. Some simply have the headspace for it, and many, living in less stable socio-economic conditions, don’t. One can say that some do not have the “comfort” of nihilism or decadence, and this is a thing that Ligotti states as well. On the other hand, this “comfort” is becoming less and less frequent.

Ligotti also uses a lot of black humor in his writings. To him it works as a microscope through which we are able to take a better look at the dark sides of the reality that surrounds us. It also works as a springboard: it helps us not to break down and fall into indifference. Then, with the necessary distance, or perspective that humor enables you with, you can look around for a virtue around which you can organize your existence: like kindness and compassion.

EB: I suppose this is what “Weird Tales of Postapoland” is ultimately about.

BZ: Yes, the idea for this comic, sparked from my view of contemporary Poland as a situation encouraging a fight of all against all, a bellum omnium contra omnes of sorts, motivated and fueled by capitalism. Some of the stories in this comic are about love, and this reflects my view that by performing some basic gestures, by simply being altruistic and supportive, this tempers the darkness around and within us. Perhaps what I’m saying is naive, but this also seems to me to be a practice that can be very easily rehearsed in everyday life. Letting go of one’s frustration or anger that the world is not the way we want it to be, and replacing it with kindness, is what’s crucial.

EB: I suppose your work as a teacher at the University of the National Education Commission in Krakow is a way to implement these demands?

BZ: Yes, teaching is a very important part of my life. If I have succeeded in something, I can help others progress towards their goals, and support those who feel similarly about the world. I also think that an important lesson that comes from all this nihilism is that if this best defines the human condition, then we’re all screwed. We are all in this very unpleasant situation. And if so, instead of fighting with each other and racing to see who’s higher, further, richer, we need to work together.

EB: I see: transcend the differences that divide us and collaborate. Obviously, it’s extremely difficult: the world is designed to discourage such cooperation, and of course, everyone also has a moment when they are simply pissed off, angry, disgusted, resentful… But I feel that you also try to reflect this in your work, there’s a strong worldbuilding impulse there. The worlds you create in different media, are very integral and detailed, some themes reemerge, some turn out to be intertwined. I also noticed that the world you draw is almost completely silent, e.g. in your latest comic book “Terrorerotic” there is almost no dialogue, no text. It’s a world we discover only through a very coherent aesthetic: the drawings, the way the plot develops, the style. All this comes back to the 1980s.: H. R. Geiger, synth pop, Cronenberg. I wonder where this attachment to the 80s comes from.

BZ: It seems to me that the world I have built for myself is largely composed of pop culture images from my childhood that have stuck with me so much so that I reference them to a degree. I remember my childhood as a land of wonder, I lived surrounded by forests, and my father telling all sorts of strange stories about eerie creatures that dwell in the woods. Horror movies on VHS that my dad showed me, cartoons about mutants, synth pop on the radio… It’s an aesthetic that I was immersed in. This childhood combination of fear and awe reminds me of a very interesting found footage horror film I watched recently, “Skinamarink”. It’s about two kids who wake up in a house with no parents, no doors, no windows. It perfectly captured how a child is afraid; how strange, magical, and terrifying the world around is. And this is something that resonates very strongly with me: I am fascinated by this original experience of fear and anxiety, which I remember from my childhood, which keeps coming back to me. So perhaps it’s natural that somewhere out there I return to the things and images that dispelled this initial anxiety.

But coming back to the 80s: as I said, if we look at contemporary visual culture or arts, many of the same questions that appeared in the 1980s are resurfacing. I also don’t feel the need to be excessively consequent, it is not that I have a retro fetish or obsession of sorts. Of course, I made one album called “Нассать на мир”/ “Piss On The World”, released by Not Not Fun, which had a story attached to it that was supposed to be set in Postapoland. I am also fascinated by a certain deterioration of sound, which is associated with analogue media, which were used more widely in a specific time. They fascinate me more than, say, contemporary digital sounds.

EB: It sounds like revisiting the past hoping for a different outcome. The mechanism behind your musical and visual worlds reminds me of the logic behind steam punk for example. I mean, starting to create a world from a very specific period in the history of humanity but interpreting it from today’s point of view: and as if everything to a certain point was happening according to the history books, and at a certain moment, it just changes course, establishing a different trajectory, an alternative history.

BZ: This is very interesting, updating the past. Like in Willam Gibson’s “Neuromancer” – still a great read by the way – there’s a recurring trope in many retrofuturistic works: some technology has been discarded and then found again, and the world of the future is built on these technologies. Maybe it’s an attempt to give yourself another chance to fix reality, proof that you can start over at virtually any point: science fiction and alternative histories show you your story (or timeline if you prefer) as a possibility, and not a necessity.

[1] Smashing Tape Records, https://smashingtaperecords.bandcamp.com/.

[2] Translation: EB.

[3] PSIZM II, 14.06. – 15.07.2023, LETO gallery, Warsaw, https://leto.pl/en/exhibitions/200-psizm-2%3Foffset%3D1.

[4] Lula passed away before the publishing of this conversation.

[5] Follow Tofu on Instagram: @tofupies.

[6] Shortly after the conversation, Bartosz Zaskórski and Jagoda Czarnowska adopted Fosfor the dog.

[7] Solo Show, „Art One Show – Bartosz Zaskórski”, https://www.instagram.com/p/CxI0ox0o2Jx/.

[8] Bartosz Zaskórski, Tomasz Zaskórski, „A Spaceship As Big As Half the Village”, 24. 09. – 28.11.2021, https://zacheta.art.pl/en/wystawy/bartosz-zaskorski-tomasz-zaskorski?setlang=1 .

[9] Bartosz Zaskórski „Fabrication”, 28.02‒ 18. 04. 2015, Centre of Contemporary Art Kronika in Bytom, https://kronika.org.pl/en/exhibitions/bartosz-zaskorski-fabrication.

[10] https://hollow-press.net/; @hollow_press.

[11] Jagoda Czarnowska, author of drawings, paintings and comics, her work can be viewed through Instagram (@ultra_kuku) and Hollow Press https://hollow-press.net/collections/jagoda-czarnowska.