Exhibition in Kyiv by Oleksandra Pogrebnyak

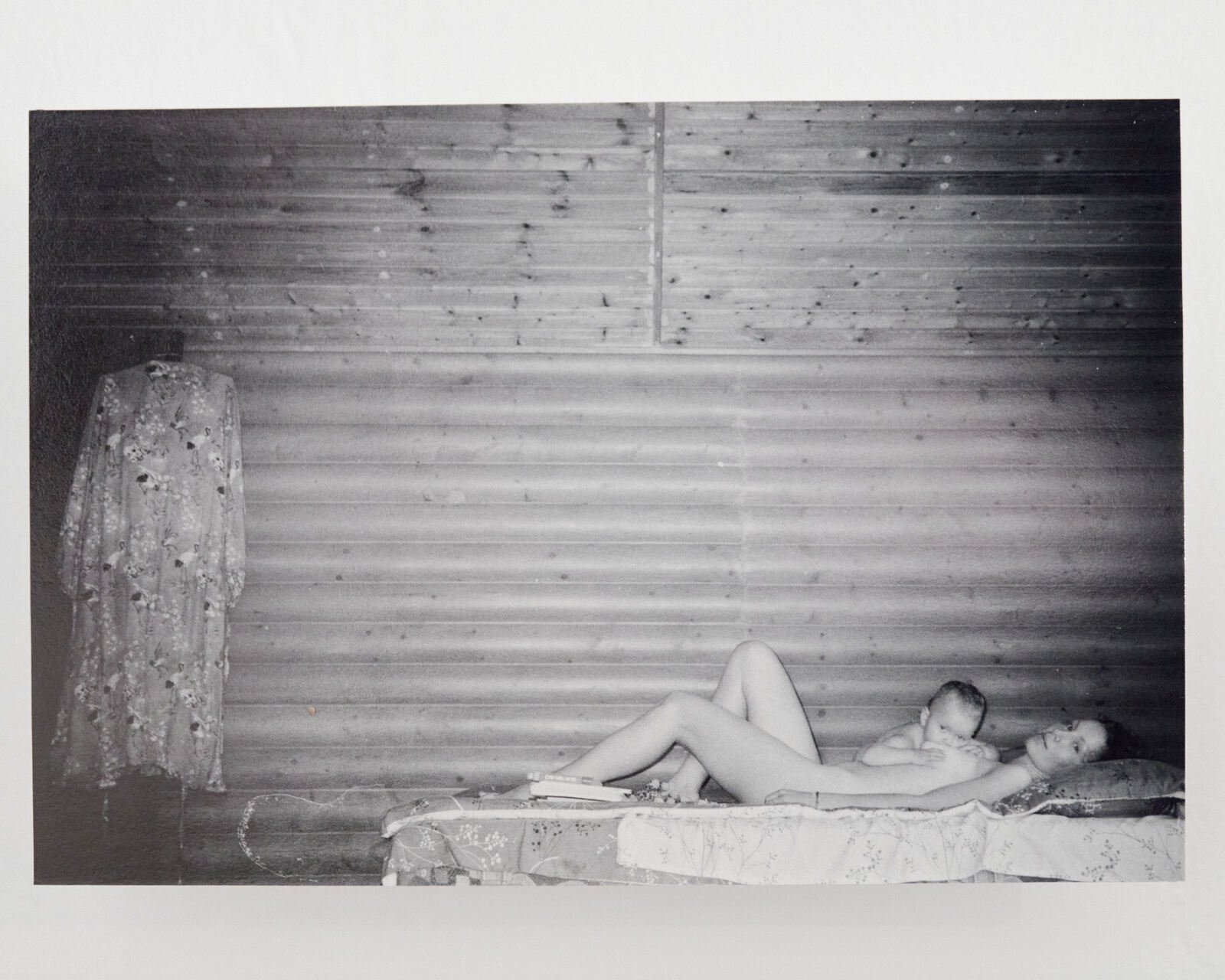

In August 2023, I became a mother. The very first weeks at home with my son Teo were marked by the sweetness and stickiness of breast milk flowing down my body and making puddles on the bed linen. When the baby feeds from one breast, milk immediately begins to flow from the other. Beyond the baby’s need for milk in the early months, the body also knows my son’s hunger — milk begins to seep through the clothes, seeking its infant. I have experienced breastfeeding as a mutually dependent process, intertwining the lives of mother and child.

My birthday is on February 24th, which coincides with the disheartening anniversary of the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. This year was the second time I prepared an apartment exhibition on this day, this time, my exhibition focused on milk. Sharing stories of motherhood during wartime without directly addressing military events, I raised questions about the nature of family, of caring in a world of interlinked crises, and our search for a safe environment.

The title — Milk for Teo — pointed simultaneously to the material and symbolic (even the magical) presence of milk in the life of a family with a child. I spoke about breasts as an organ that in women, serves others, bodily transformation as a natural process, as well as mythical thinking and imagining the time ahead. I am grateful for motherhood as it has allowed me to regain my ability to think about the future.

The exhibition took place once again in the apartment of my childhood. All the works existed among our plants, books, Teo’s toys, and other personal belongings. When I curate an apartment exhibition, both the connection to the place and my experience working in a large art center are significant. Many hours spent in a specific space are always beneficial for understanding how your exhibition decisions can impact the viewer’s experience. In the case of the house where I have lived for many years, this understanding comes naturally.

One of the first works that opened the Milk for Teo exhibition was a photograph of a little girl, Rada, dreamily floating in the water as if in a milk pond, as I interpret it. It is a part of the long-term, ongoing photo series I am. Rada by the incredibly sensitive artist Katya Lesiv, Rada’s mother. The second photo that was presented from the series is their joint portrait during breastfeeding. Much smaller and slightly hidden in the plants, one could discover it while sitting in an armchair nearby. The image reveals an important narrative for me — feeding as a physiological process, and the idea that a woman’s breasts belong to her child.

On the opposite side of the room, as if it were spilling out of the bookshelves, was a pink-beige skin colored silk cloth with a hand-embroidered message: “I am going home to eat mulberry from the tree” from Katya Lesiv. The work registers the will yet acknowledges the impossibility of enacting this desire due to the uncertainty of war. Together with her daughter, Katya relocated to a safe country. The longing for home, expressed in the notion of the mulberry tree that bears fruit during the summer months and invites one to eat directly from its branches, deeply resonates with me. In the text accompanying last year’s exhibition — Thickets, Groves, Woods, and Bushes — I shared that curating that exhibition was the only possible way for me to embrace the circumstances that had begun to shape our lives since martial law was enforced. This year, I feel it more than just emotionally. I need to document the process of the physiological changes that have happened to my body, and those which my son is rapidly undergoing, nourishing himself with breast milk and immersing himself in the world we have created for ourselves, for him.

In the same space on the first floor, there was a playful series Filling, which Zhanna Kadyrova started in 2006. Zhanna is recognizable for her technique of covering various surfaces with tiles. This work constantly adapts to its context, and for us, Zhanna created an installation using our dishes, filling cups and pots with ‘milk’ (white glossy tiles). I like to talk about this work as a material presence of milk everywhere; milk as a fluid that fills everything in family life with a child. One of the cups Zhanna used was gifted to us after a previous exhibition, it was part of the display then. It features two of the four slag heaps by Roman Khimei – the series of photographs assembled into one landscape in the work Four Slag Heaps From Which One Can See The Occupied Donbas. Roman took these photos in Myrnohrad (the Donetsk region of Ukraine) together with his father-in-law, Oleksandr Ulianov, a former miner. The collage was made just before the start of the full-scale offensive, on February 23. Among miners, there’s a tradition of giving ceramic cups with printed photographs on Miner’s Day (the last Sunday in August). In 2022, Oleksandr Ulianov and Svitlana Ulianova were already in Kolomyia (the Ivano-Frankivsk region) on this day, far from their home.

We moved through the space to discover the drawings of Zoia Kadan, daughter of artists Anna Zvyagintseva and Nikita Kadan. It is important to note that these are not the works of a professional artist but drawings by a child who doesn’t identify herself professionally. Most of Zoia’s drawings from before the full-scale war depict smiley animals or human faces, but there is also a more recent drawing of an explosion near a building. I exhibited them in agreement and dialogue with Anna and Zoia, to tell a story about the connection between mother and child, and between the different generations of artists in their family. Anna comes from an artistic family and often addresses this in her practice. For example, Sculptures of My Father from 2013, the small objects made of twisted foil from candy wrappers that refer to the daughter’s treasure findings in the workshop of her father. This work was a part of my previous apartment exhibition. Later, she created an homage to her grandfather Rostyslav Zvyagintsev (To Plant A Stick, 2019-2022), a well-known painter. A cutting of a willow is planted in a field of the Ukrainian Polissia (the Rivne region) where we watch it grow, capturing the tender connection between the artist and her family in a landscape that was a great source of inspiration for Rostyslav’s paintings. If Zoia chooses to become an artist when she grows up, she will also have a specific connection to this family heritage, and the generations that worked in this profession before her.

Coming to the second floor of the apartment we encounter Tamara Turliun’s massive installation Pollinator House. When you look at these cocoons, you don’t know which creature or insect has made them, and for me, this aspect of questioning rather than answering, is the critical element of this piece. It also strongly refers to the transformations that happen everywhere, those which are a part of the world around us, natural cycles or processes. This state of transition is constantly with us (Ukrainians) since the escalation of the war, and for me now in particular, when the period of pregnancy changes into motherhood.

In one of the rooms was a work by Kateryna Lisovenko. Despite being an artist known for her overtly political stance, for Milk for Teo, she cultivated a utopia. Her large-scale painting depicting simultaneous feeding and drinking, embodies a harmonious symbiosis. The female centaur is leaned down towards the creek, drinking its waters. Her two small babies are nourishing themselves from the breast and the udder simultaneously, all engaged in this process of drinking, together. The peacefulness of the scene she creates is hardly possible in our lives today. How acceptable is escapism in a country at war? Should we experience the presence of war so intensely every day? Is it possible to allow ourselves a space where we can hide with our children and their milk? Motherhood has become this safe territory for me – the utopia where you can feel protected, even if only for some moments. And now we, too, are becoming the safe environment, the literal sustenance, for our son Teo.

In another room, the girl in Laure Prouvost’s film Shadow Does (2023) tells her grandmother about the world that has faced changes. It is imperfect, but it’s her world. The narrative intertwines humanity’s achievements and losses, and reveals antagonisms, asking what is “normal”, because for a little girl, the world she describes is the only normal world. It is the one she knows, the world she’s been familiar with since birth. This year, this is the only work by a non-Ukrainian artist. I reached out to Laure after seeing her works at the Venice Biennale in 2019, where she represented the French pavilion curated by Martha Kirszenbaum. When the full-scale invasion started and Kyiv was at risk of being surrounded and occupied, it was a period when any civilian life in the city had become frozen. We communicated intensively externally. We wrote letters to international colleagues and institutions describing our experiences: explosions were heard all around us, we knew the Russian army had entered the nearest suburbs. Dozens, maybe even hundreds of such letters were sent. One of these letters was to Martha Kirszenbaum. She started sharing our stories on Instagram, eventually inviting us to collaborate on a film program for Liste in Basel.

Sometimes I think that the number of circumstances is overwhelming: the war started on my birthday, we stayed at home to take care of our plants. A missile hit my grandparents’ house in Moshchun (the Kyiv region), and our family went to rebuild it. My husband Dmytro Chepurnyi and I got married on the 17th day of the invasion, and now, we are raising a child. At some point, the layering of these events makes it hard to believe it’s one life, a life during wartime. And I feel like these stories resonate for many people. Our lives are not just about destruction and loss. Yes, that surrounds us, but there are also stories of hope, which I try to highlight in these now annual birthday apartment exhibitions.

Milk for Teo created a happy utopia over several days within our apartment, unfolding between the exhibition and the shared experiences of visitors particularly. It was a safe space co-created by female artists. Like in the warm, rippled ‘milk’ for Rada, or the idyllic drinking of a centaur family, or the captivating world of a little girl told through her own voice; these are the peaceful islands we need to construct for ourselves, a plot woven by belonging, devotion, and care that empowers.

I’m aware that as Teo grows older, he will encounter the consequences of this war. He will discover the traces of war on the streets of his home city, Kyiv, and beyond it. One day he will come to Ukrainian Luhansk, the city of his father, and visit those long-abandoned fruit trees in the yard of Dmytro’s childhood home, about which he will have heard about countless times. He will be constantly coming across firsthand war experiences because everyone around him will have their own stories to be told. But I also know that he will feel secure. His breath won’t be stolen by a loud sound. Now, I allow myself and my son to dissolve into the idyll of early motherhood as I dream that growing up, he will carry the feeling of being protected; that he will recognize his belonging to this land and the country where he was born, and that his world will be magnificently exciting with all of its flaws and virtues.

Artist(s): Tamara Turliun, Katya Lesiv, Zoia Kadan, Zhanna Kadyrova, Roman Khimei, Kateryna Lisovenko, Laure Prouvost

Exhibition Title: Milk for Teo

Link: https://www.instagram.com/p/C4iQi-Ttgh8/?img_index=9

Venue: Private home of Oleksandra Pogrebnyak, Dmytro Chepurnyi, and Teo

Dates: 24-25.02.2024

Curated by: Oleksandra Pogrebnyak

Photos by: Ruslan Synhaiewsky, Vita Kotyk, Dmytro Chepurnyi, Vsevolod Kazarin