Julija Šilytė

Julia Bryan-Wilson is a scholar, curator, and writer whose work has been central to feminist and queer art history and visual culture over the past two decades. She is Professor of Contemporary Art and LGBTQ+ Studies at Columbia University and core faculty at the Institute for the Study of Sexuality and Gender. Bryan-Wilson’s writing has been particularly influential in showing how art can be animated through language, and how bodies, labor, politics, and form can be held together within scholarship. Her study of Yvonne Rainer’s Trio A, shaped through her own embodied engagement with learning the choreography, has offered a powerful model of how the art historian’s body can figure within research itself. More recently, her monograph on Louise Nevelson, written alongside reflections on wildfire, care, and precarity, revealed again her singular ability to braid rigorous art-historical scholarship with attentiveness to lived experience. Bryan-Wilson is also Curator-at-Large at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP), where she co-organized major exhibitions such as Women’s Histories, Histories of Dance, and Queer Histories, and in 2024, she served as President of the International Jury of the 60th Venice Biennale. This interview took place on the occasion of her public lecture Queer Histories at Sapieha Palace in Vilnius.

Julija Šilytė: You started your academic journey with literature and then turned to art history. Why did you see visual culture as the home for your ideas?

Julia Bryan-Wilson: I was a literature major and I always liked reading. Fiction and poetry have always been my first love and are still my greatest love in terms of cultural production. Of course, I obviously care deeply about visual art, but my primary attachment on a visceral level is to literature and poetry.

When I was applying for graduate school, I had started organizing little shows with friends in scrappy spaces in Portland. I was working with Miranda July [American film director and writer] on this feminist, DIY chain letter project [part of the Riot grrrl scene]. I was thinking about image making, the moving image, and what people do with very little resources.

I had also studied AIDS activist videos in college, and those things were converging in my mind. For activist or interventionist and dissident purposes, visual culture is a rich terrain and I wanted to study longer histories – that was one reason that I got a PhD in art history.

Now I feel grateful to my young self for making that choice because while I am very passionate about art, I didn’t professionalize my love of literature. When I now read poetry or novels, that’s just for me. When I go to a museum, as much as I’m excited, it’s my occupation now and so it has a different mood.

JŠ: It sounds like energy distribution – when one part seems empty, you can call on the other.

JB-W: I get a lot of inspiration from the novelists and the poets that I read. It sometimes makes its way into my writing, but it’s not what I’m teaching. I’m not a critic of those things. It was a quite naïve choice I made because I was 21-22 when I applied to graduate school, but I look back and I think – wow, unintentionally, that was a great act of self-preservation. If my professional interests, work life, and my most passionate connection to creative practice were all one thing, I would be, who knows…I think it would be a little crazy.

JŠ: Let’s talk about your approach to pedagogy. In one of your classes at Columbia, you create a syllabus together with your students. How does that work? What political or epistemic stakes do you see in this horizontal model of teaching?

JB-W: I’ve been teaching full-time for more than 20 years. I am constantly, restlessly experimenting with different forms of pedagogy and trying to make an effective classroom. I still believe in teaching and the practice of education, although it’s very under threat right now everywhere, but in the US in particular.

Very special, extraordinary things happen in collective conversations. I would say some of the most truly thrilling moments of my life have come out of conversations in the seminar when students bring their own knowledge to bear on a subject.

There’s one graduate seminar that I have taught where we make a collective syllabus together – Queer Feminist Theories in Art. I am trying to model new forms of education that are more horizontal and collaborative. To me, that’s a queer feminist method of thinking and knowledge building.

The students break into groups and they suggest readings for the weeks. It comes partially out of what they’re interested in or what they’re curious about. They have to trust that it’s going to work. Of course, some people come in on the first day and they freak out. They don’t want anything to do with it because they want to see the syllabus. They want that reassurance. A syllabus is like a roadmap, and it’s comforting to see that you know where the course will end up.

But I don’t like to position myself as the arbiter of all knowledge. I am voracious about trying to take in as much as I can, but I also want to honor what the students are coming to the table with, what they are interested in, what they’ve been reading. It’s a more organic way to learn from each other, showing that it’s not just about one expert or authority, but that we’re all in our own way, building expertise and sharing that expertise.

JŠ: Has this collaborative teaching experience influenced your writing and scholarship?

JB-W: It’s more the other way around. My writing and scholarship have often been collaborative. I’ve co-written a book, I’ve had many conversations with friends, I’ve co-written articles, especially with my very close friend, Natalia Brizuela, and we have just curated a show together – Lotty Rosenfeld: Disobedient Spaces at the Wallach Art Gallery in New York City.

I was thinking more about how I can bring that sense of dialogue into the seminar space. It’s not always completely successful. You have to accept the risk and the possibility of some unevenness. But the students emerge feeling very confident in the knowledge because they’re so tied into the making of it. It’s also about emboldening them to realize that making a syllabus is hard. Theoretically, you could draw from anything that’s ever been uttered, published, printed, broadcasted. It’s like making soup with the world’s largest pantry and no recipe. It’s a kind of magic alchemy to fit together texts that speak to and build on each other. In this course, students practice doing that, which is great because a lot of them want to go on to be teachers. So it’s also an experience for them to see what it is to think forward.

JŠ: It’s very reassuring to hear that there are spaces for this kind of pedagogy. I was also thinking about your curatorial roles and this other path that you’re paving simultaneously with teaching and writing art history. At your talk in the Sapieha Palace in November, you presented your co-curated exhibition Queer Histories at the São Paulo Art Museum (MASP). You also just opened Gutsy, at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw (MSN). I’m curious about these international collaborations that you’re forging. Could you talk about the work of translation – not particularly linguistic, but rather cross-contextual – that you engage in during these processes? How do you think about your work in relation to this local–national–international framework of writing histories?

JB-W: It goes back to collaboration. On my own, I have a lot of limitations. I am very embedded in my own framework and national context, of course. I would never want to be the kind of curator, critic, writer, or teacher that just parachutes in and has grandiose ideas that are disconnected from the local scene.

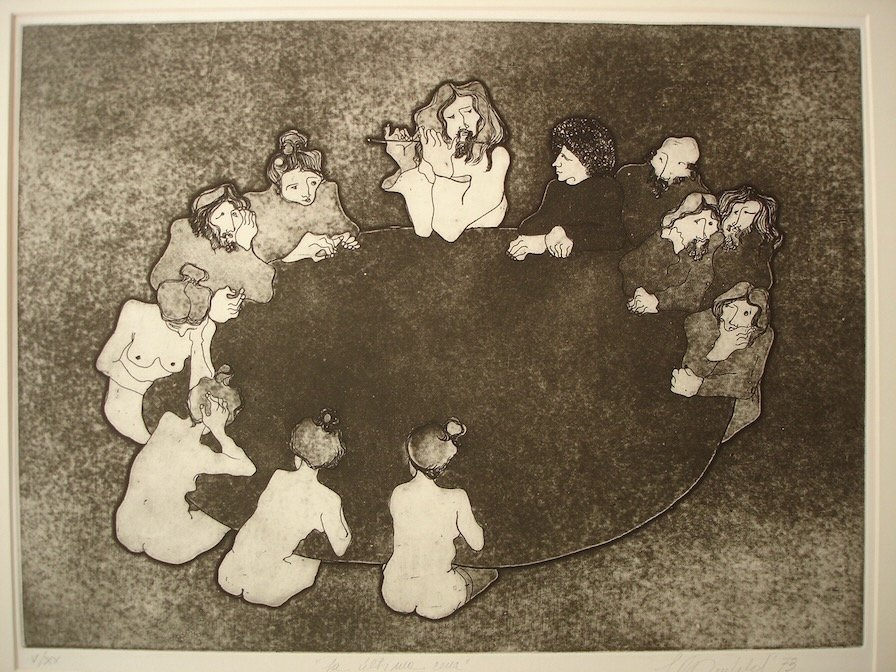

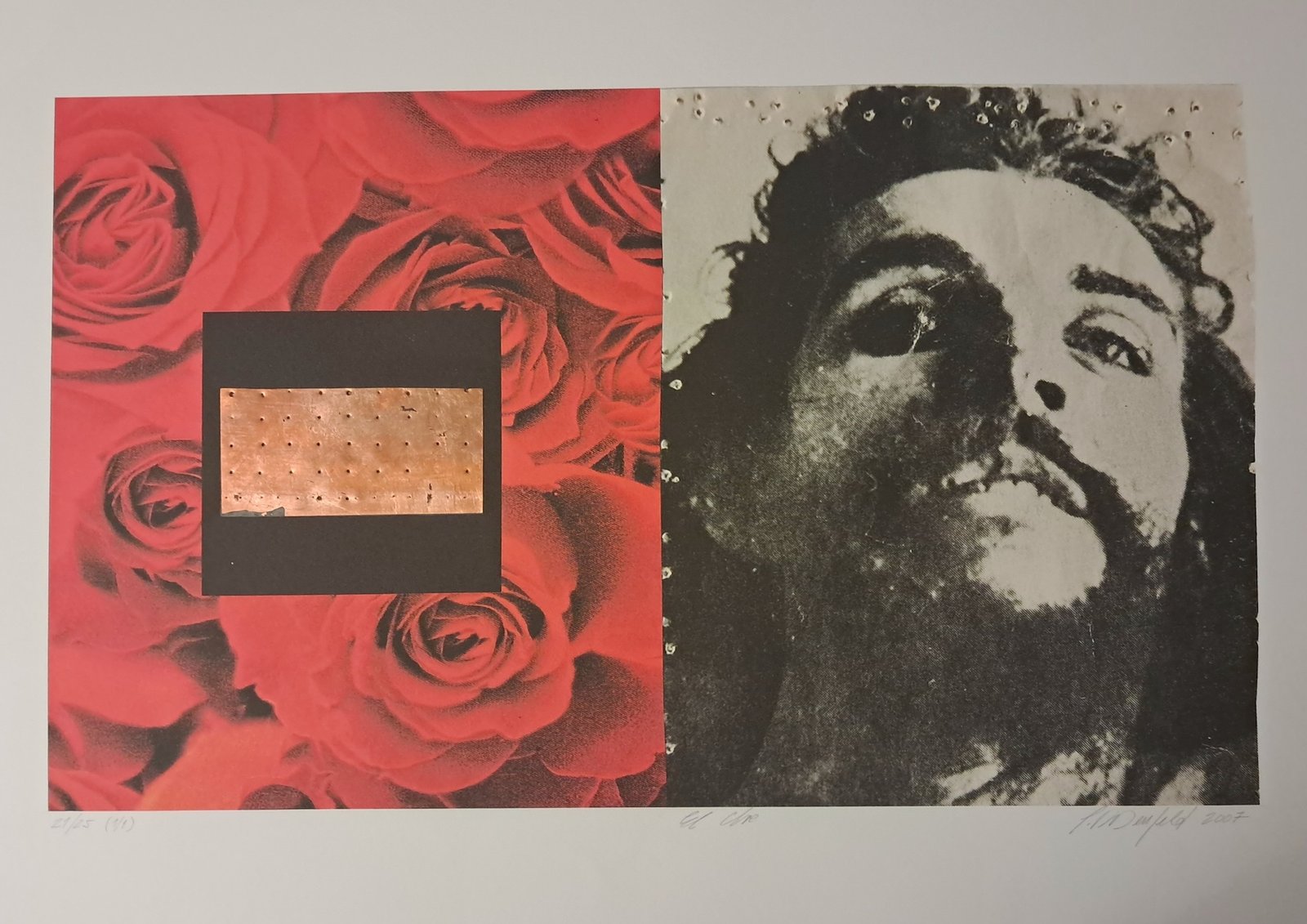

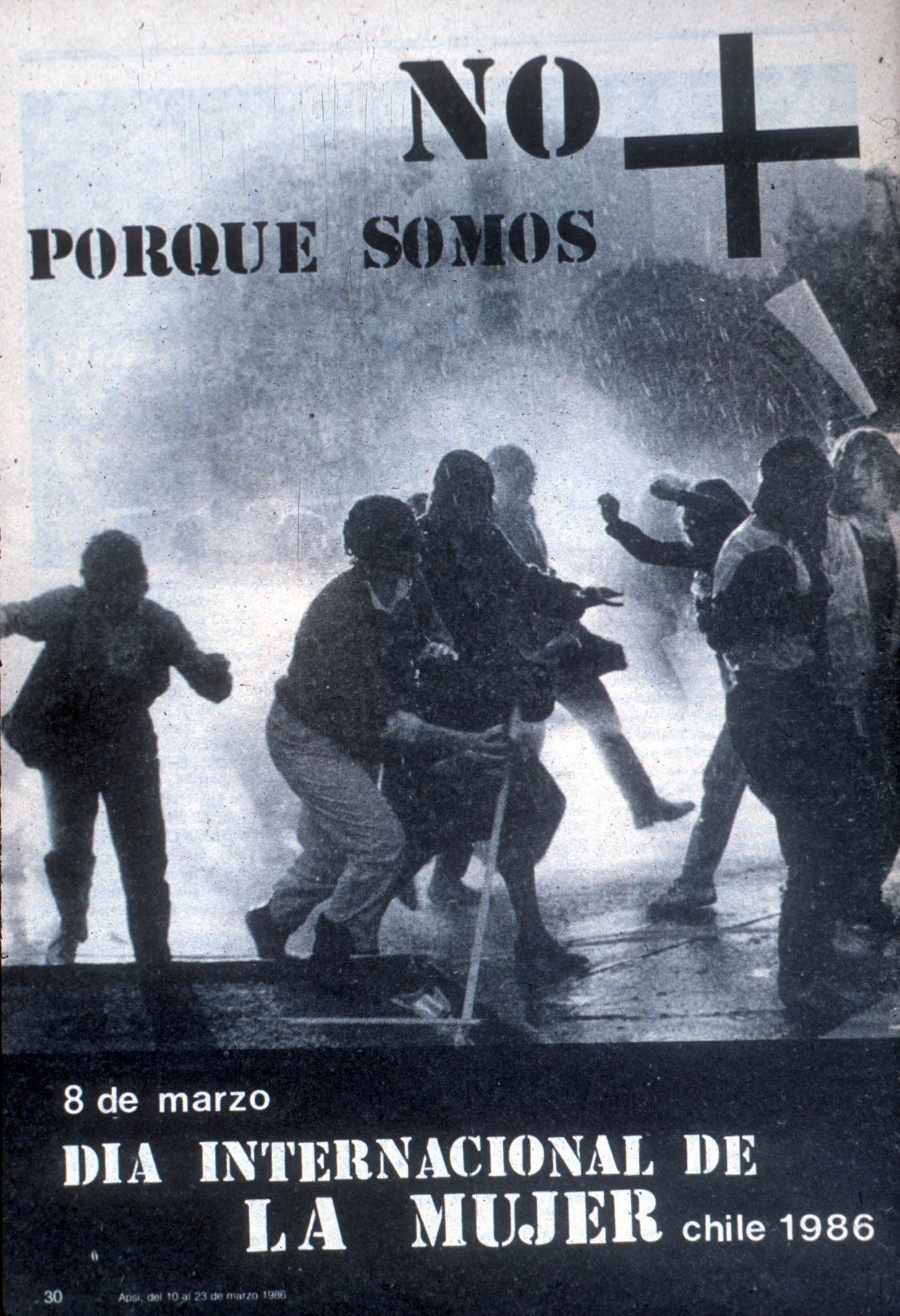

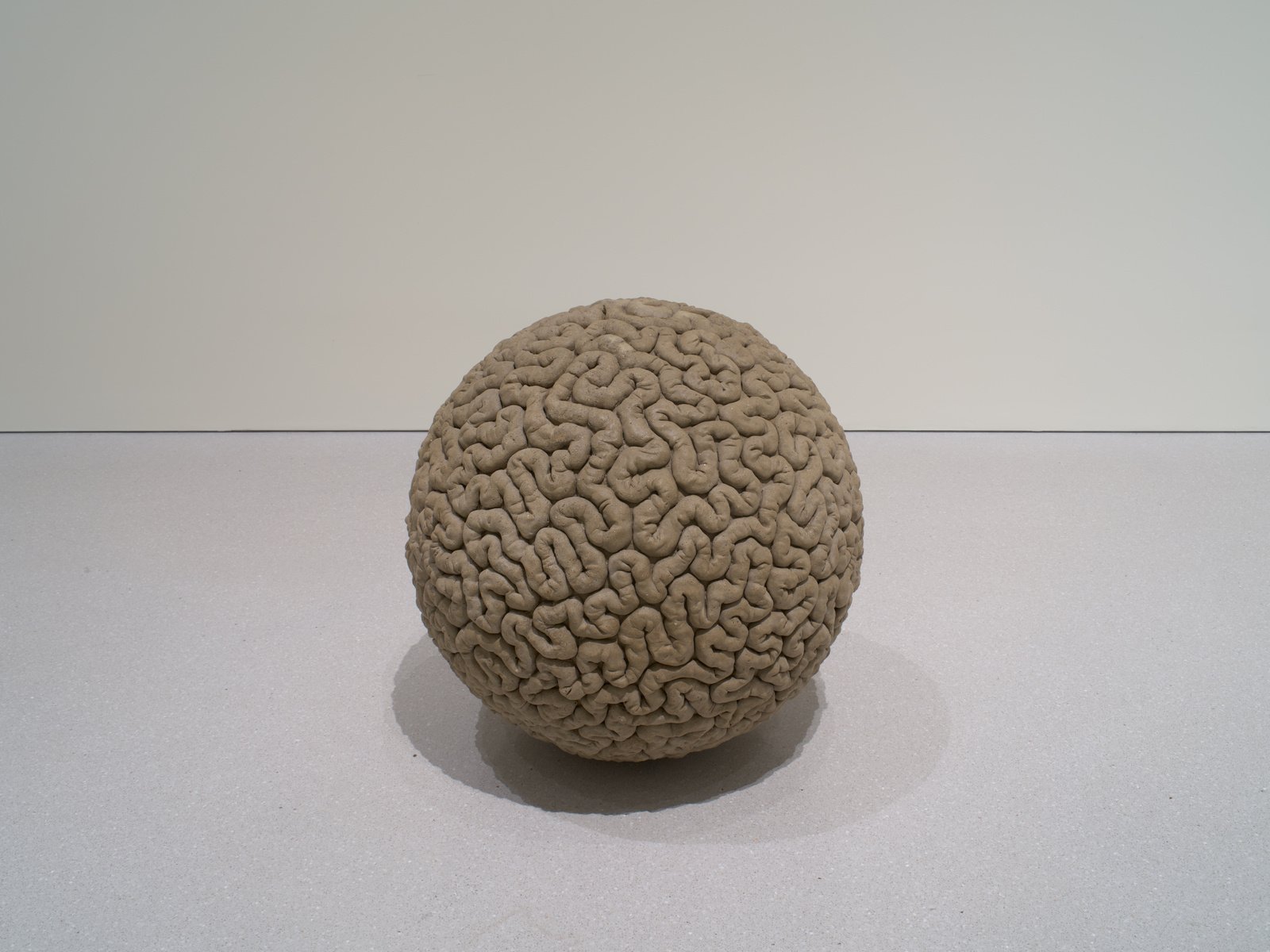

I didn’t curate Queer Histories on my own. We were a team of five and I was the only person who wasn’t Brazilian. In terms of the show I just opened in Warsaw, Gutsy: On Feminist Infrastructure, I had several site visits and I did have someone on the curatorial team who I worked closely with, Jagna Lewandowska (from the curatorial team of MSN), and made sure that I was thinking carefully about the Polish context. I should also mention that Gutsy is one of four smaller shows at MSN focusing on feminism that were independently organized but presented collectively under the umbrella title City of Women. These shows act as a complement to the blockbuster exhibition The Woman Question 1550-2025, curated by Alison Gingeras. Gutsy presents abstract and allusive works, which are an interesting counterpoint to the figurative painting in The Woman Question.

I was very interested in the site of MSN as it is now located in the shadow of the Palace of Culture – the Stalinist skyscraper – and just a few meters from the boundary of the Warsaw Ghetto. My show is ultimately an opposition to the fascist body and to fascist efficiency systems. Most of the artists in this show in some way or another have grappled with authoritarianism or dictatorship and are positing leakiness, desire, inefficiency, non-functionality, excessiveness, slumping, aging, sagging: all of these other forms that bodies can take, that are often feminized bodies.

JŠ: Perhaps it’s also important to trace these connections as a way to see that the national or local histories might resonate with international struggles.

JB-W: Totally. One thing that we tried to do in Queer Histories was highlight how trans women are situated in many different places and also to include many versions of trans-indigenous cosmologies across South America. Though they have interesting resonances, they are not at all identical.

In Gutsy, it was so important to my own politics to put artists who were making work under military dictatorships, for example, in Chile and Brazil, next to Alina Szapocznikow, an Auschwitz survivor and Jewish artist from Poland, next to Palestinian artists. Not that it’s a show explicitly about resistance to oppressive regimes; it’s a show about bodies and viscera and organs and systems – the body, the building, the nation – but there is a politics to that, to trying to showcase some of those affinities.

JŠ: In your critical monograph Louise Nevelson’s Sculpture: Drag, Color, Join, Face, you talk about fan art dedicated to Nevelson. I haven’t heard much about fan art being included in art historical scholarship. Do you think art historians should think more about reception and spectatorship?

JB-W: That was a part of the book I am still proud of. There really hasn’t been a complex conversation about hobby responses to so-called “fine art” because social art history, which I was trained in, focused often on reception in the press – the reviews, the published commentary at the time. The idea that there would be amateurs, or people who don’t have a public voice, making art in response to things and then sending those responses directly to the artist or having a drag show about it has not been a widespread part of how we think about reception. The fact that there was such an outpouring of people who were inspired by Nevelson’s art and also inspired by her independence as a woman felt so important. Also, kids making school projects about her art…all of this helps us see how the artist’s legacy changes over time.

Maybe such reception studies will happen more because things are living online now, and we have access to some of these materials in a different way. I had colleagues at the University of California Berkeley, for example, a scholar named Abigail De Kosnik, who’s a theorist of fan studies, an internet and TV scholar, and she is one of my closest friends. It was helpful to be in conversation with her as I was writing this.

There’s also a lot of negative fandom. The most toxic forms of critique often come from the fan space – think about public figures like John Lennon getting assassinated by a fan. Fandom can twist into this incredible, negative obsession. It prompts strong feelings.

JŠ: What is something that gives you hope these days?

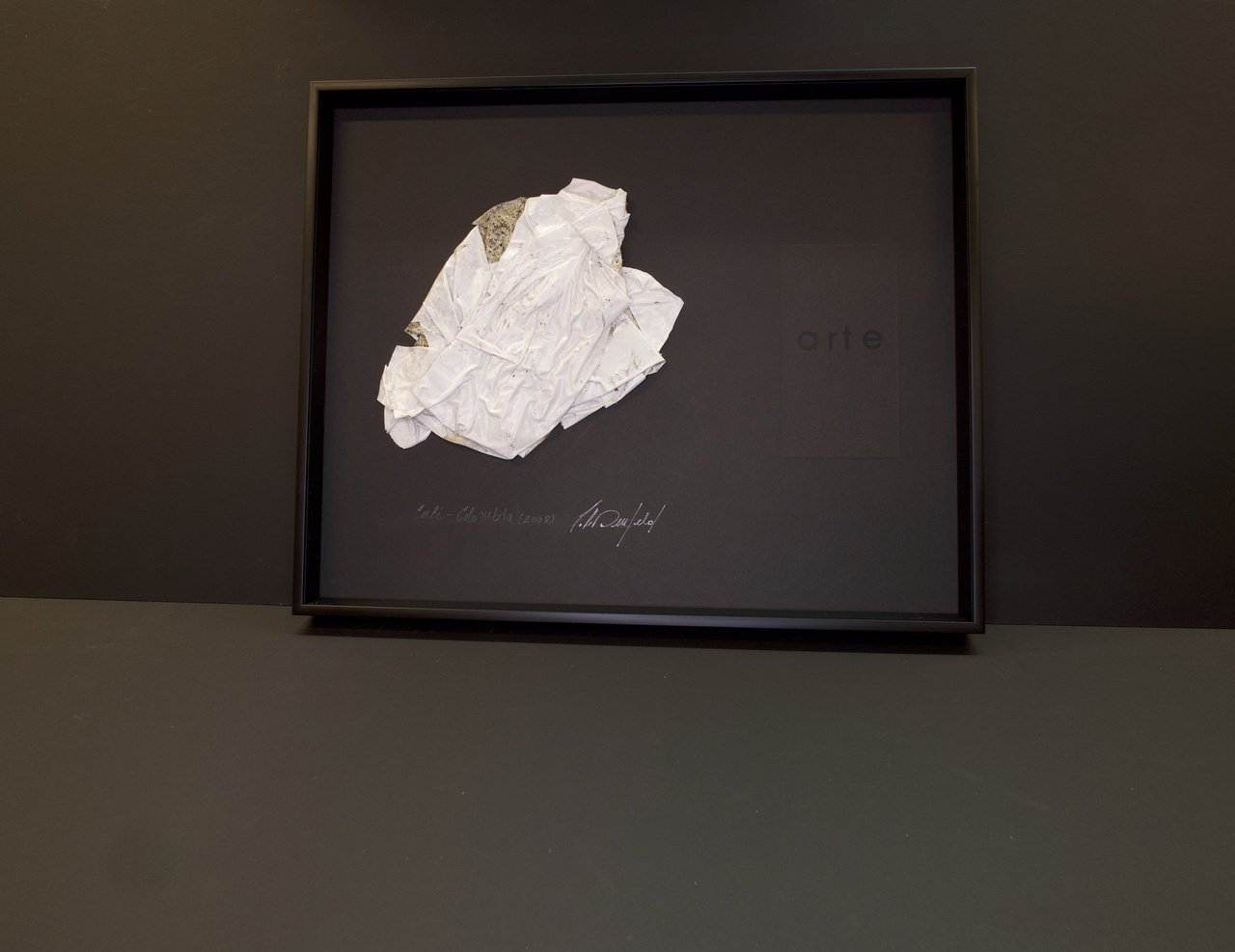

JB-W: I consider myself almost in a post-hope condition – hope can feel really elusive and fleeting. But I look to the work of artists like Lotty Rosenfeld, who continued to resist during seventeen long years of the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile (1973-1990), who made work in collaboration with other artists and writers, and that offers me a model for how to keep going. The show I curated about Rosenfeld demonstrates how her collective practice was vital for survival.

And I really wanted to hear more about the protest that just happened here in Lithuania and across the cultural sphere – the November 21 protest. I was especially interested in farmers on their tractors making music with their horns. Something about this solidarity inspires me. If people on tractors are showing up for a protest about the cultural sphere, I want to be there. That’s my kind of protest. There’s so much cross-contextual creativity in that as well, in how we understand that our struggles are related. That gives me a lot of hope.