Lizaveta German

On December 30, 2024, I received a very special and entirely unexpected gift – a silver ring. Rough and elegant at the same time, it had several engravings on its exterior side:

KY

IV

KOKHAN

[Kh]

UA

2024

KOK

HAN

Vitaliy Kokhan, an artist, jeweller, and dear friend, made and presented the ring to me. Aside from three types of his author’s signature stamps (I guess he was hesitant to choose which one best suited his craftsman identity), the ring held some very simple marks: the city (Kyiv), the country (UA for Ukraine), and the year. As simple as that, he indicated when, where, and by whom this piece was made. For me, it has a deeply personal meaning: in 2024, I returned to my home city, Kyiv, after 2,5 years of exile, to live next to my family and community in a country that is still at war. I look at these subtly engraved lines and catch myself thinking: but indeed, there was this year and there was this city, and there was this artist and his simple, yet meaningful gesture of making me literally wear my own memory, encapsulated in just a few words and figures. And, indeed, I wear the ring on a daily basis; it has become my charm and an essential part of my everyday look.[1]

The ongoing russian–Ukrainian war is often referred to, among other things, as a “war for memory”. It is a struggle over historical narratives and the weaponisation of memory, russia’s efforts to erase Ukraine’s distinct identity and install its own version of history. The topic of memory, while largely historical, those dealing with events of the current war have become in demand, even trendy, among artists in Ukraine. In contrast to larger narratives, the concept of private, if not intimate, memory and how one can inscribe it (metaphorically and literally), has become central to Vitaliy’s practice over the recent years.

In his pre-war practice, Vitaliy was mostly focused on what I dare to describe as the elusive allure of the world, material and immaterial, addressed both in terms of form and content. He usually worked with solid materials such as stone, marble, concrete, and various types of metal – the body of his oeuvre was remarkably substantial. In contrast, he also occasionally experimented with more ephemeral elements such as a spider’s web, or growing crystals (for example, Objects with Contingent Marks of Natural Processes, 2018, which was included in the exhibition of artists shortlisted for the PinchukArtCentre Prize that year) or natural, found materials as seen in his countless contributions to Borderline Space land art symposium from as early as 2004 (Mohrytsia village, Sumy region), or even a shadow (Shadow Concentrator, 2023, for Internally Displaced Landscape project). In all of those cases, his careful attention to expose the material’s tactile realness was far from mere formal playing around or striving for decorative appeal. It rather dealt with deconstructing the nature of each chosen material or medium to reveal its own uncultivated beauty. And by doing this, he guided us in finding the same integral qualities in the surrounding world. We tend to put mind over matter when interacting with art; Kokhan challenges our preconceptions and gently pushes us to acknowledge its raw physicality alongside the feelings it opens up within us.

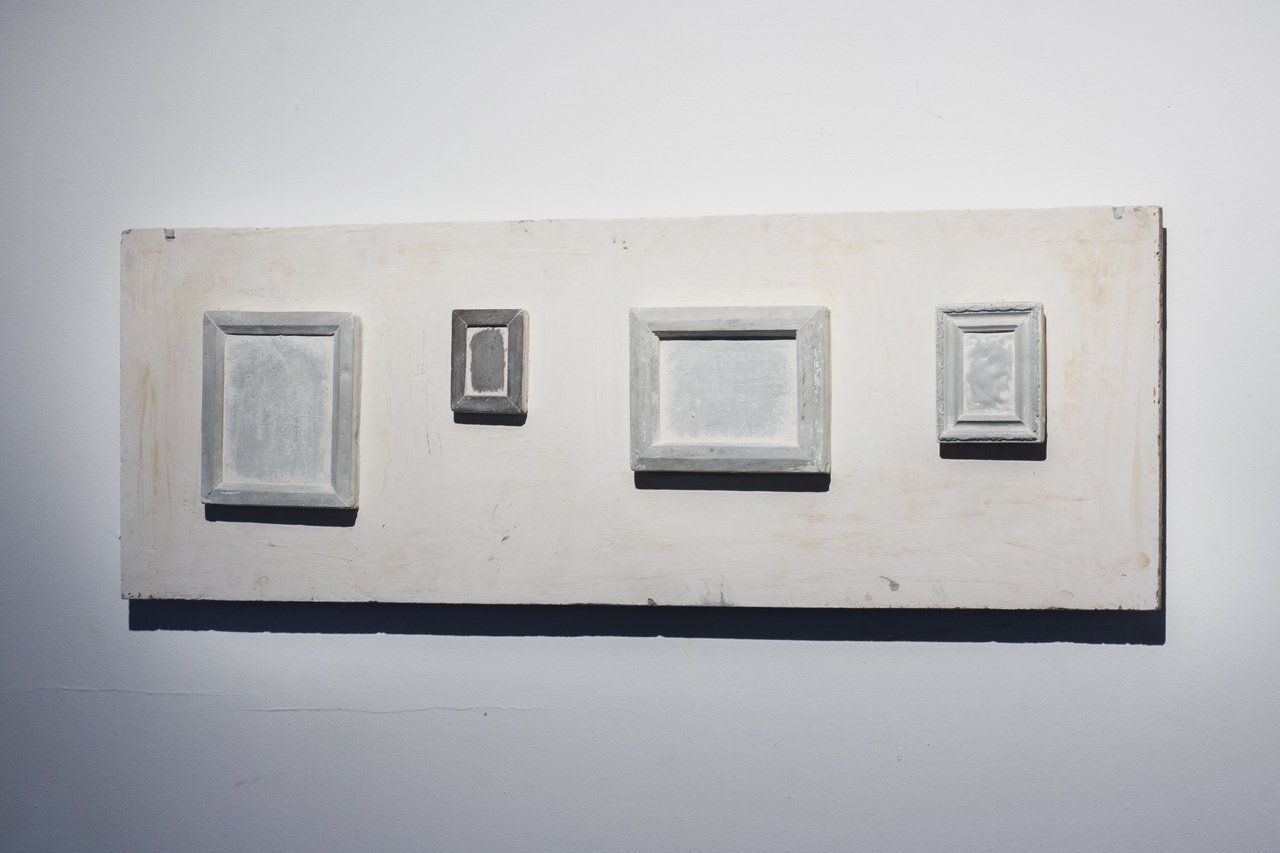

In the case of the Untitled series (2017), Kokhan compared the expected exquisiteness of classic painting with the rawness of concrete. To reveal the essence of a painting’s objectness, Kokhan made moulds of heavily framed canvases and then poured concrete reliefs out of them. Lacking image per se, these paintings instead acquired their weight and expressiveness through the essential nature of their very form.

Another reference is the sculptures from the show CIRCA 2020 (The Naked Room, 2020); a series of human-like sculptures of different dimensions, shapes, and materials. Here, the artist juxtaposed the grandeur and optical stability of the female figures (achieved through the use of the classical Greek stance of contraposto) with the lightness and fragility of cardboard and papier-mâché. While smaller, more tender pieces are made from cast iron – heavy and thick. From prehistoric art to XXth-century modernism, as Maria Lanko and I commented on the series back in 2020, female statues have remained possibly one of the most popular and hackneyed genres. But Kokhan wasn’t afraid to take a step into the genre’s banality and consciously exploited it as a “zero form.” Sculpture served him as a sort of vessel to complete quite a different artistic task. Professional sculptors can hone the details of their models for months until they achieve the perfectly desired, controlled results. Kokhan opened up his practice for something he could not predict – a mistake, a production failure, or the reaction of a capricious material. He referred to this as “setting the unplanned on the rails.” A traditional sculpture is complete and final in its form, but the very process and conditions of its creation often stay invisible. In his work, Kokhan set an open experiment with material and form, each of which opened up a myriad of sculptural potentialities.

CIRCA 2020 was also the first instance of using words and numbers (for example the show’s title) to hint at the importance of time and when a work comes into being. It’s not the particular year that ends up being significant, but rather the time period that something belongs to. Precise for the spectators of today, this timestamp will sooner or later become arbitrary (“circa”) for the researchers of the future, where blurred lines between particular years won’t play a major role. This move brings us to his newest works, but also to the method he himself describes as archaeology of the present day. His intention here is to examine what he has produced from the distance of an imagined future era, as if trying to learn something about the past from these headless bodies, made “circa 2020.”

In August 2024, Vitaliy produced an in-situ work for the exhibition Sense of Safety at YermilovCentre – one of a few active cultural hubs in Kharkiv, a large city next to the russian border under constant shelling. The artist engraved “This is evidence of the presence. 18.19. August 2024” directly on a concrete pillar of the gallery to make it a permanent part of its interior. The date engraved indicated exactly the period he was working on the commission, being present and performing his labour there and then. This seemingly simple gesture raised several questions: How do we safeguard small gestures and personal recollections in an age of collective narratives, such as an unfolding war in one’s home country? How do we support the preservation of these recollections in the digital era, when anything can be conjured and consumed in seconds, but also, due to that very fact, can also lose its value in the same span of time? And, what kinds of memories do we consider meaningful anyway, when we live in a post-truth epoch when, to paraphrase a line from Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem, no memory is final?[2]

As banal as it may sound, the ongoing war has been teaching Ukrainians to cherish smaller moments of quiet joy. Kokhan partially plays with this sentiment and seeks a substantial – and timeless – way to preserve such moments artistically.

Engraving simple yet eloquent phrases was a method he employed in several works exhibited at his solo show, Forever Today, at The Naked Room in 2024, which was dedicated to his own vision of memorial sculptural language for the near future. There, next to mid-size objects like a plane, pyramid, and obelisk, he hung several heavy plates made of sandstone, marble, and travertine. On each of them, we see the inscriptions like:

EVERY DAY IS

LIKE ANY OTHER

15 Sep 2024

ATTENTION

—>

23d of May

Year of 2024

Kyiv

Again, as in the case of the pillar in Kharkiv, Kokhan basically documents nothing more than the very humble fact of his (or our, the viewers) mere existence at a given moment in time and space. But there is also something almost biblical in the way he imbues those random dates with an enigmatic flavour of significance: there was evening, and there was morning: day 935. Maybe, contrary to the words sung by David Byrne in his 2018 hit, not every day is a miracle. But certainly every day counts when you live through the 4th year of a full-scale war. And, obviously, a pinch of dark humour (a very handy survival tool during these war years) is also present, as he juxtaposes statements that celebrate life with something that clearly resembles a tombstone.

A man of few words and a slow working pace, Kokhan is the kind of artist who seems to be driven by an inner silence and unspoken feelings rather than outsourced inspirations. “There are things that you simply have to do, or you’ll lose your sense of self,” he says, answering a mundane question about what drives his work. For Kokhan, art is a way to occupy, to fill in the world (metaphorically and physically) with new meaning – and, thus, to reduce the space that is left for the meaningless. To combat entropy, I would add. To no surprise, his main body of work is very substantial. It manifests its own volume and corporeality – owning the space in which it is displayed. Curiously enough, in his latest works, he doesn’t generate new forms. On the contrary, he reduces and cuts out of the found ones.

In his most recent project for public space, In Memoriam of Us All, Kokhan addresses not an individual but a collective experience of living through the war, based on the specific case of a very particular group – inhabitants of Northern Saltivka, a massive sleeping district in Kharkiv.

Memory and trauma work in a tricky way. In the cities in the rear like Kyiv, recollections of the first months of the initial russian offensive in 2022 are now partly faded by the seemingly normal everyday life of the megalopolis, and even regular nightly shelling no longer cancels the flow of daytime life. There’s no need to remind the locals of Northern Saltivka that the war goes on – they literally live in its gargantuan traces. The area is about 30 kilometres from the russian border. In 2022, the defence line passed through some of the neighbourhoods, and the russian troops were as close as two kilometres from the school chosen by Kokhan as the spot for his work. Not a single building in the area remained undamaged; some are still inhabited and eligible for reconstruction while others have been demolished or are slated for it.

In 2024, memory culture platform Past/Future/Art organised a project called Memorialization Practices Laboratory for artists and researchers. Through lectures, workshops, site expeditions, talks with local communities and authorities, participants discussed and designed possible new approaches to the memorialization of the russia-Ukraine War. Kharkiv was one of the key cases discussed, and Kokhan was among those who took particular interest in developing ideas for a temporary memorial site there, drafting several proposals for further discussion. Born in Sumy, Kokhan spent more than a decade in Kharkiv, which cultivated in him a special affinity for the city.

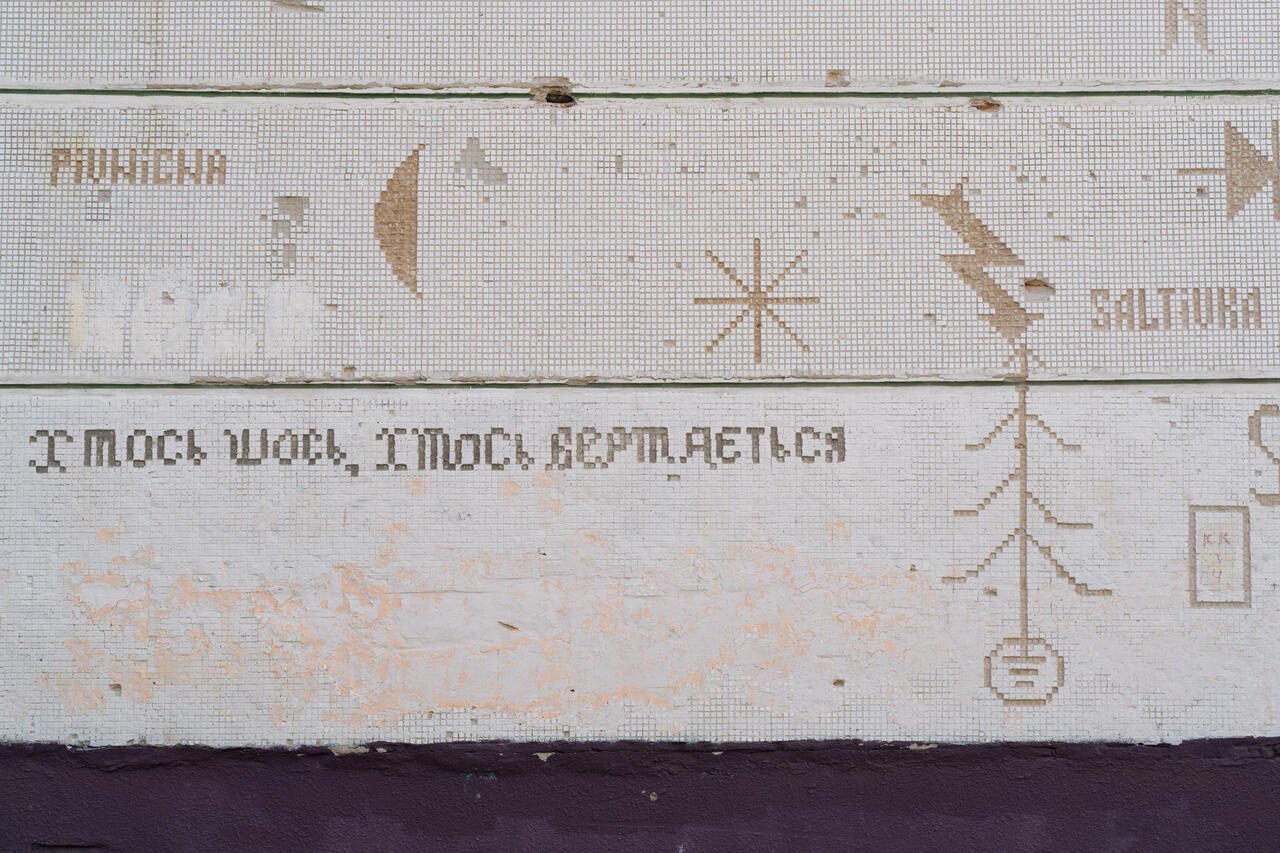

After visiting Northern Saltivka in 2024, following the program, he thought about inscribing text-based messages on the facades of different buildings and creating a route through the neighbourhood. Later in 2025, the artist, in dialogue with Past/Future/Art’s curator and commissioner of the final piece, Kateryna Semenyuk, chose a single site for the final piece – school №165, with its walls left solid but wounded by shrapnel. Originally covered with small, square, white tiles, many of them had fallen off during explosions, revealing the bare concrete underneath. Kokhan took over this existing “ornament” created by the holes and used it as a technique itself – by cutting out even more tiles, he created a sequence of simple drawings and texts that referred to the local experience. Phrases like “The war goes on”, “This wall is a witness of horrors from 24 February 2022”, “Someone whatever, someone came back” or “Mordor — 35 km”[3], as well as simplistic images of a car, a cat, a trident, etc. illustrate the everyday reality of the area in a manner that feels casual, as if the works were created by an anonymous street artist. The inscriptions are a mash-up of past events and are indicators of the artist’s own presence there and then, working on the mural in the summer of 2025.

ON JULY 12th

TREES WERE FALLIN

G

IT’S RAINING

OUTSIDE. t +26

JULY 21 2025

THE WAR GOES ON

Graffiti culture, Ukrainian traditional embroidery, and locally famous wall writings by Kharkiv outsider artist Oleh Mitasov were among his points of reference. But the main one was the ruin itself – he wanted these inscriptions to look natural among the cracks and missing tiles. Who knows how many new cracks will appear over time and under what conditions – “natural” or otherwise? The predesigned temporality of the project is informed by the unknown destiny of the school – and the whole district. The school is eligible for reconstruction, but it is unclear when the children (who are currently studying online) will be able to return physically. In regards to the title, In Memorium of Us All, Kokhan wanted to dedicate the piece to some particular distinguished person but wasn’t sure who exactly would be appropriate or necessary. Finally, he thought about all of us – each and every one worth remembering for anything or for nothing, simply by living through these years; these years of the full-scale war.

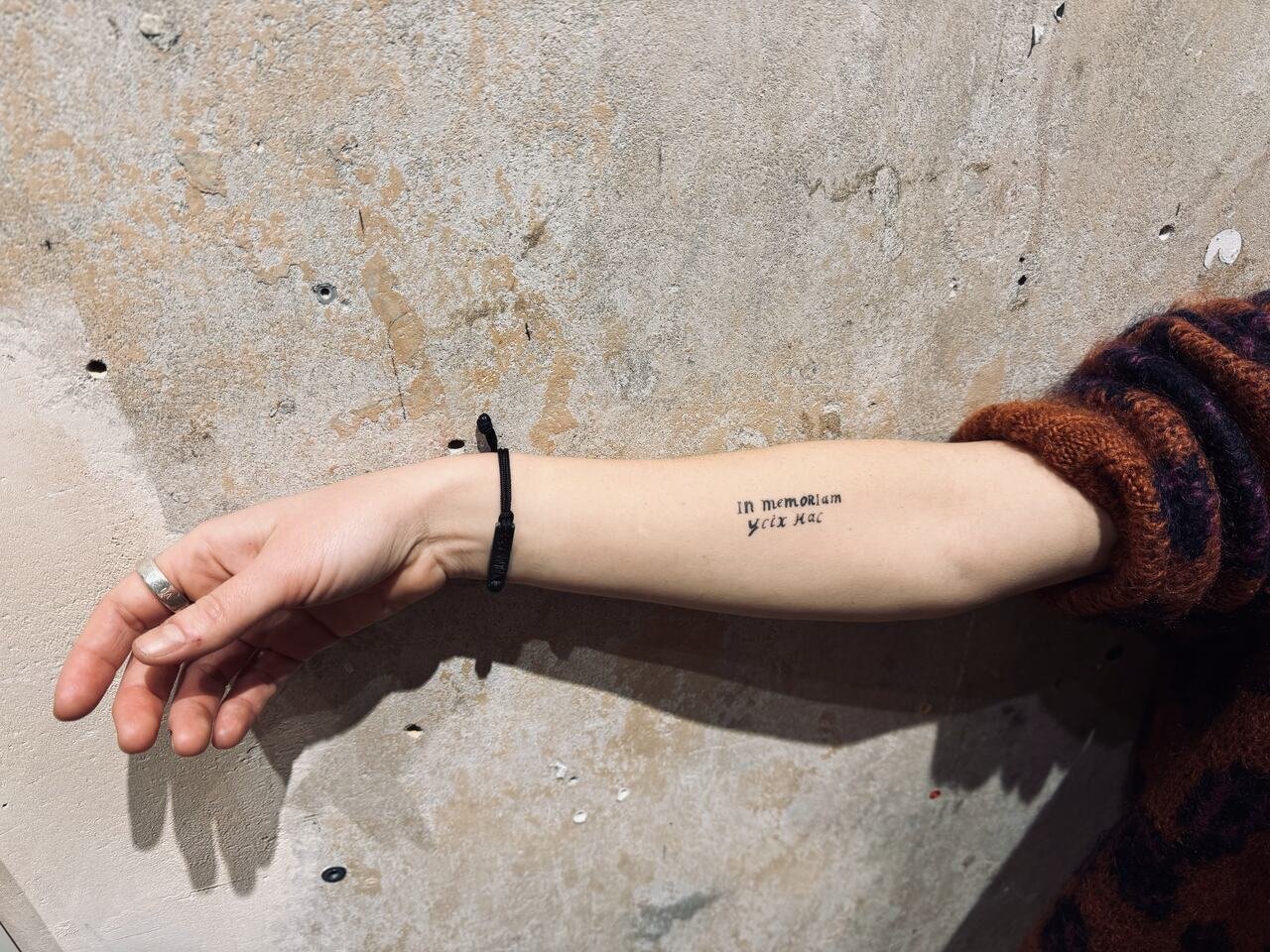

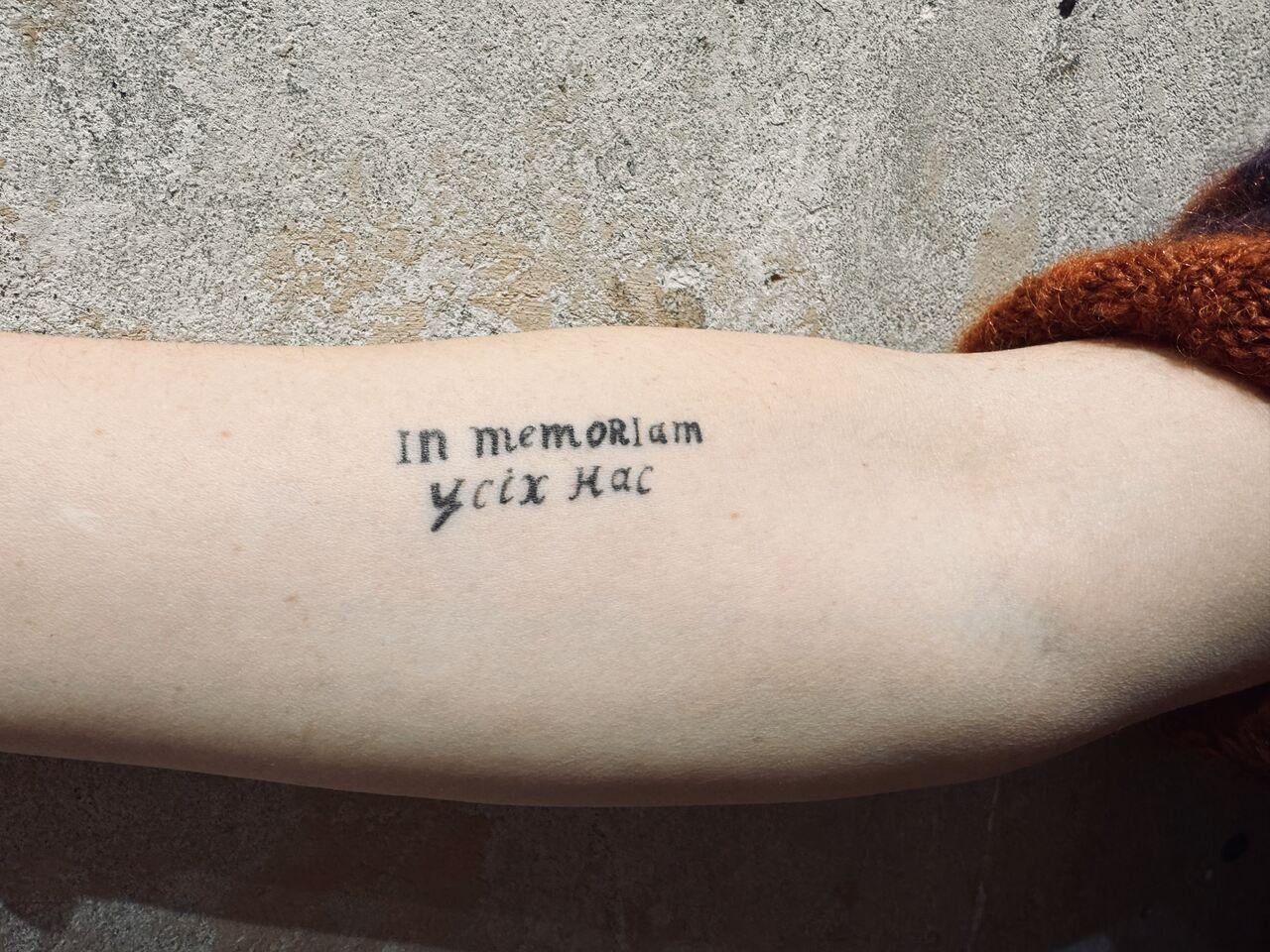

Kokhan refers to his mural work as a “tattoo.” The building, a metaphor for the human body, which translates its inner condition, senses, thoughts, and memories to the outer world through its “skin” (surface) in a clear visual language. Unlike celebrity street-artist Banksy, whose murals in liberated districts of Kyiv which were made in 2022, were severely criticised for their superficial nature and lack of real connection to the community’s sense of tragedy, Kokhan created his humble statement after numerous conversations with local community and council, initiated and facilitated by Past/Future/Art. “The most interesting thing in art for me is that when something new is created, you cannot imagine how things were before it existed,” the artist speculates on his idea of art’s general purpose. The time to summarise any collective experience and install big, solid monuments is yet to come. The precarious status of Kokhan’s monument reminds us not only of the shaky nature of our own memories, but also of our desire to enshrine, even if only for the time being, things big and small, which may be important simply because they happened to us.

***

For me, the artists in my life help to give shape and form to our messy ideas about the world we live in. Kokhan’s sharp, minimalistic gestures seem somehow more trustworthy than my own ability to recall, twisted by war-related trauma and ADHD. I am not sure what exactly I want to preserve about the past 34 months for the rest of my life, apart from my child’s birth. But I do want to keep those undefined memories nearby anyway. So I thought, the best thing would be to keep a memory of my own self – as one of Us All – and to never forget that all of this did happen, indeed.

[1] That year, Kokhan produced a number of other silver items like pendants and pins with similar stamps. One of those pins was spotted by Borys Martynenko, an art collector, businessman, and leader of one of the mightiest military units conducting drone warfare. Borys commissioned Kokhan to design pins with special insignias to award the distinguished servicemen and servicewomen. As the artist recalls, he felt that creating such objects was the most suitable way to be useful as an artist.

[2] Originally, “no feeling is final”, a line from Rilke’s poem “Go to the Limits of Your Longing”, as translated from German by Joanna Macy.

[3] In everyday speech, russia is often called “Mordor” as a symbol of absolute evil, while russian soldiers are often called “orks” as in The Lord of the Rings saga.