Veronika Treitiak

In the prolonged course of war, in conditions of instability, the contours of the future change daily and the only thing one can predict is catastrophe. Yet after a catastrophe, nature always recovers, as if under the influence of a strange will. Permanent Home of Displacement opens a portal into a space where the catastrophe has already occurred: exile has happened, memories of home remain. And, remembering within the walls of Garage33 is not a gesture of return, but rather an act of awareness – for something must vanish to be understood.

Silence, the rumble of a train, and a river – this was the setting of the exhibition Permanent Home of Displacement. It served as a repository of Crimean Tatar art by four female artists and one male artist, created as part of a residency curated by emerging curator Vita Kotyk. The exhibition was organized by Ukrainian contemporary artist and curator Maria Kulikovska together with Canadian curator and visual artist, Dana Neilson.

The residency itself functioned as a kind of laboratory for exploring memory, which operated across several focal directions: archival, corporeal, and historical research, portfolio and self-presentation development, reflection on political and personal experiences, and the presentation of Crimean Tatar art within the context of both the Ukrainian and the global art scenes. The residents are five artists, each with their own unique history connected to the peninsula. They explored their memories in every possible way, delving deeper into their origins to study and make sense of this phenomenon of memory – and then, through the exhibition, to share that understanding with others. As an example, during the residency, the participants immersed themselves in the themes of family archives and collaborated with Crimea Platform and Danish Youth Center, or explored issues of Crimean Tatar heritage together with the National Art Museum of Ukraine.

All the works presented in the exhibition were created during the residency with the exception of one piece by artist Sevilâ Nariman-qızı, which organically found its place in the exhibition and truly belonged where it was displayed. As well, the earlier works of Yusuf Abibulaiev were also included as he ultimately could not take part in the residency due to being mobilized into the army.

Historically, Crimean Tatar art hardly fit into the Ukrainian canon, shaped under the influence of Soviet historiography with its emphasis on folk traditions. In such a paradigm, the heritage of other cultures, including Crimean Tatar, have remained overlooked. Today though, more than ever, questions of survival, protection, preservation, and remembrance are primary, and are inseparably linked to the need to integrate Crimean Tatar art into the Ukrainian context, and so with this in mind, this exhibition serves as a doorway into a world where the future grows through the fragments of the past.

When we remember, the semantics themselves become important: who, where, and how someone perished; who survived, who lost their home, how exile occurred and how it repeats today. Each of us has our own story connected to the peninsula. Such an account requires an eternity and its own scenography.

Permanent Home of Displacement was situated in the hidden corners of the city. In this space, one wants to remain alone with each artist – without obstacles and noise – to hear their voices: familiar, yet entirely other. From time to time, locomotives pass by the exhibition, and the clanging of heavy metal overlays the stories of exile, recalling the very trains that once carried Crimean Tatars to foreign lands. Later, the curator leads visitors to a nearby river. Its clear waters and the light gliding across the riverbed mingle with the rumble of the trains. In this interplay of sounds and images, a sense of eternity emerges.

Curator Maria Kulikovska, who was born and raised in Crimea, recalls that her life there was inseparably linked with the Crimean Tatar community. Neighbors, friends, daily encounters shaped a feeling of unity – and simultaneously of constant repair, incompleteness, in which everyone lived. This atmosphere resonates in the exhibition: a space still under construction becomes a site for displaying art.

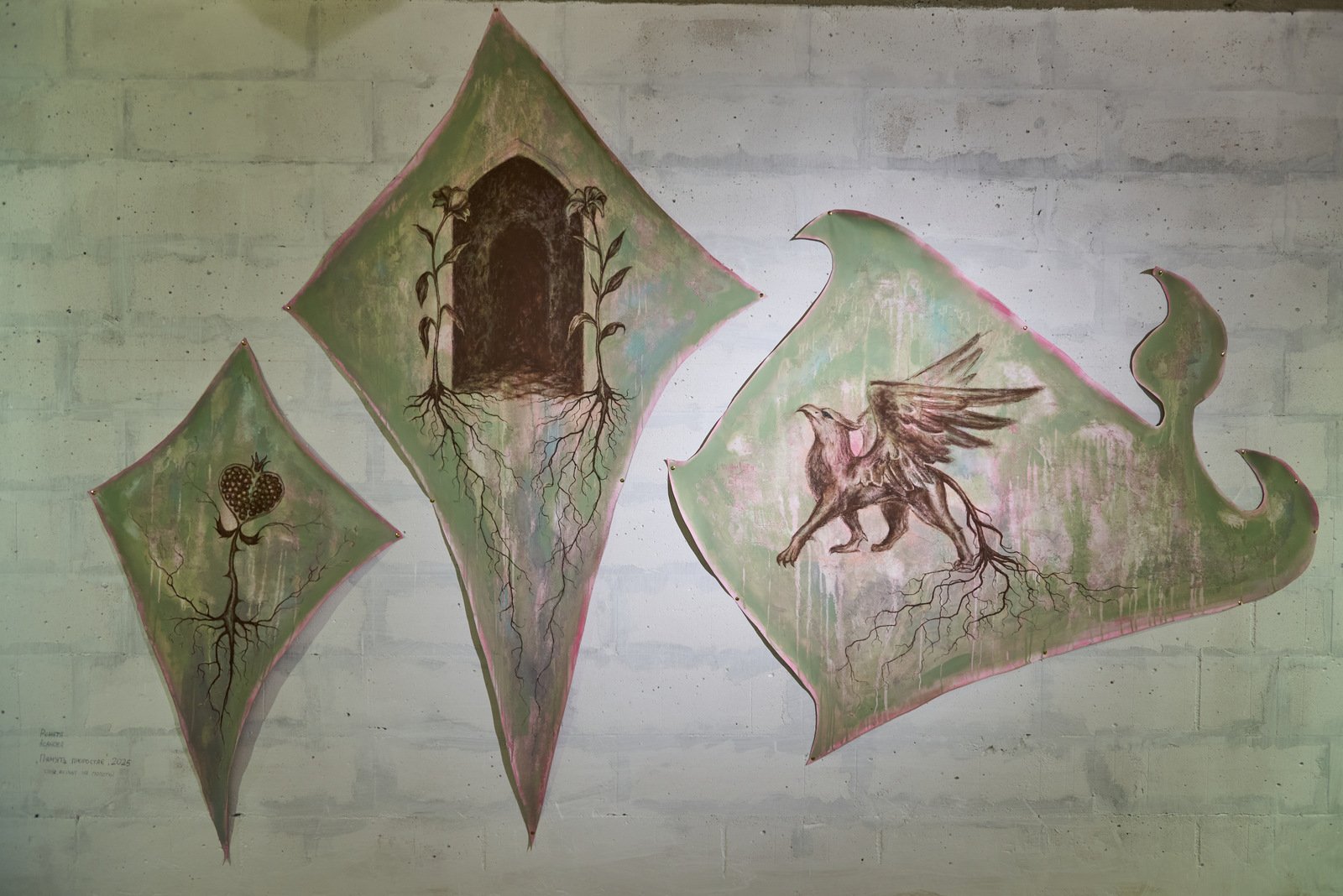

Renata Asanova is the only artist in the residency who has never been to Crimea. Her family – Crimean Tatars – were deported first to Uzbekistan then forcibly relocated to Kyiv due to the occupation of the peninsula. Renata’s work Memory Grows, from the project Garden of Memory is the first piece you encounter upon entering the space of Garage33. The work consists of three parts suspended on the wall, resembling a disjointed triptych. It resembles fragments of memory through three Crimean Tatar images: the pomegranate – a symbol of fertility and identity, connected to the female line, the mosque – a symbol of search and connection to the past, and the griffin – a protective and courageous symbol present on the Crimean coat of arms. All these images have roots, but they seem suspended, torn from the earth, emphasizing the artist’s feeling of separation from her native land.

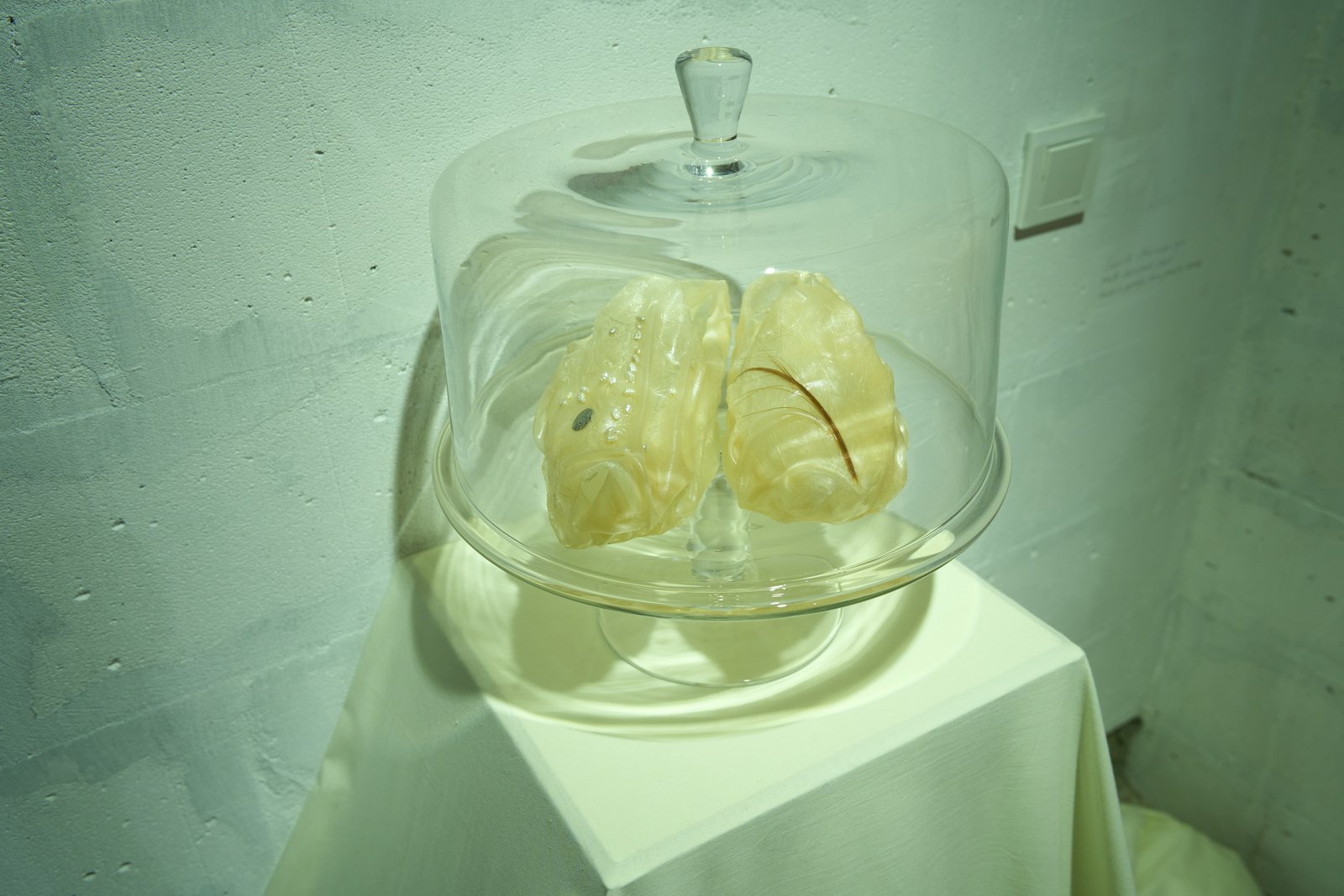

The second part of Renata’s project is Kvitkostvorinnia (Flowercreatures), from the project Garden of Memory. Here she works with different materials, including clay; textures and colors creating works that reference a landscape she has never seen. This landscape comes to life through memories and stories shared by friends, forming a mythical image of her homeland. The works also reflect the influence of the Crimean Tatar ornament örnek, with depictions of decorative plants.

Sevilâ Nariman-qızı has a different story. She was born in Kezlev to a family of Crimean Tatars who preserved the memory of their lineage. While still in Crimea, she lived within the community, studying its culture and traditions – themes that became the foundation of her artistic practice. One of her works, Selsebil, is dedicated to ancient Crimean Tatar fountains. Originally, these were sources of fresh water and simultaneously refined architectural and acoustic objects, embodying the coexistence of people and nature. During the Russian imperial time which launched colonial narratives, these fountains were transformed into decorative “Fountains of Tears”, losing their original meaning. Fountain of Tears is the popular name of the fountain in the Bakhchisaray Palace, built in 1764. It is associated with a legend that became widely mythologized through Pushkin’s poem, in which the Khan commissions a fountain to mourn the untimely death of his beloved concubine. As Ukrainian literary critic Oksana Schur notes: “While tourist tours there once focused on the history of the Crimean Tatars, the main attraction now is the Fountain of Tears, which the Russian national poet Alexander Pushkin once described in his poem ‘The Fountain of Bakhchysaraj’.”[1]

Through this work, Sevilâ emphasizes the importance of preserving authentic cultural heritage. The work takes the form of a fountain, standing alone and leaning slightly against the wall – the entire surface is dedicated to it. The transparent fountain resembles a soaked veil the color of skin, over which water seems to flow.

The exhibition also features Half-Barefoot – an earlier work made of epoxy resin and silk, shaped like a pair of shoes. Transparent, they reveal embedded pearls, strands of the artist’s own hair, and a Crimean Tatar as well as an akçe coin, from the era of the Crimean Khanate. The shoes speak of colonization, deportations, and loss: the artist describes them as being repeatedly taken away from their intended place, symbolizing the endless cycle of deprivation and recovery that mirrors the history of the Crimean Tatar people.

On the second floor is Elmira Shemsedinova’s work Family Nest. Its story begins with her grandfather, an artist and architect who sketched old Crimean Tatar homes, many of which disappeared during the Soviet era. After 2014, Elmira traced her grandfather’s steps through Crimea but by this time most of the houses had been destroyed or rebuilt. Their memory was preserved only in his drawings. No longer maintaining a physical presence, they have gradually been transformed into myth. Elmira repeats this gesture: she recreates the home based on her grandfather’s old sketches, adding a texture reminiscent of fragile paper, along with thickets, symbolizing that nature would have been a better fate than oblivion. Trees seem to grow through windows, invading the exhibition space. One can imagine standing in the yard of this house, on the edge of the water.

The exhibition also features a series of personal works Untitled, by artist Yusuf Abibulaiev. During the residency he was mobilized, so the displayed works – a landscape and a portrait – were selected from his studio with his sister’s permission.

The landscape, executed in a more abstract style, opens space for interpretation. Curator Maria Kulikovska notes that those familiar with Crimea may recognize the colors of the sea or the night steppe. The forms in the work – a tree, a figure, a house – evoke images from memory. Today, Crimea is unreachable, and all that remains is remembrance. The second work is a portrait of his beloved, his muse. This love was unrequited, and the artist returned to the canvas every evening: painting her face, erasing it, and starting anew until one day he left the portrait untouched, perhaps in a moment of acceptance. This gesture captures the attempt to hold onto closeness and to find love, even in solitude.

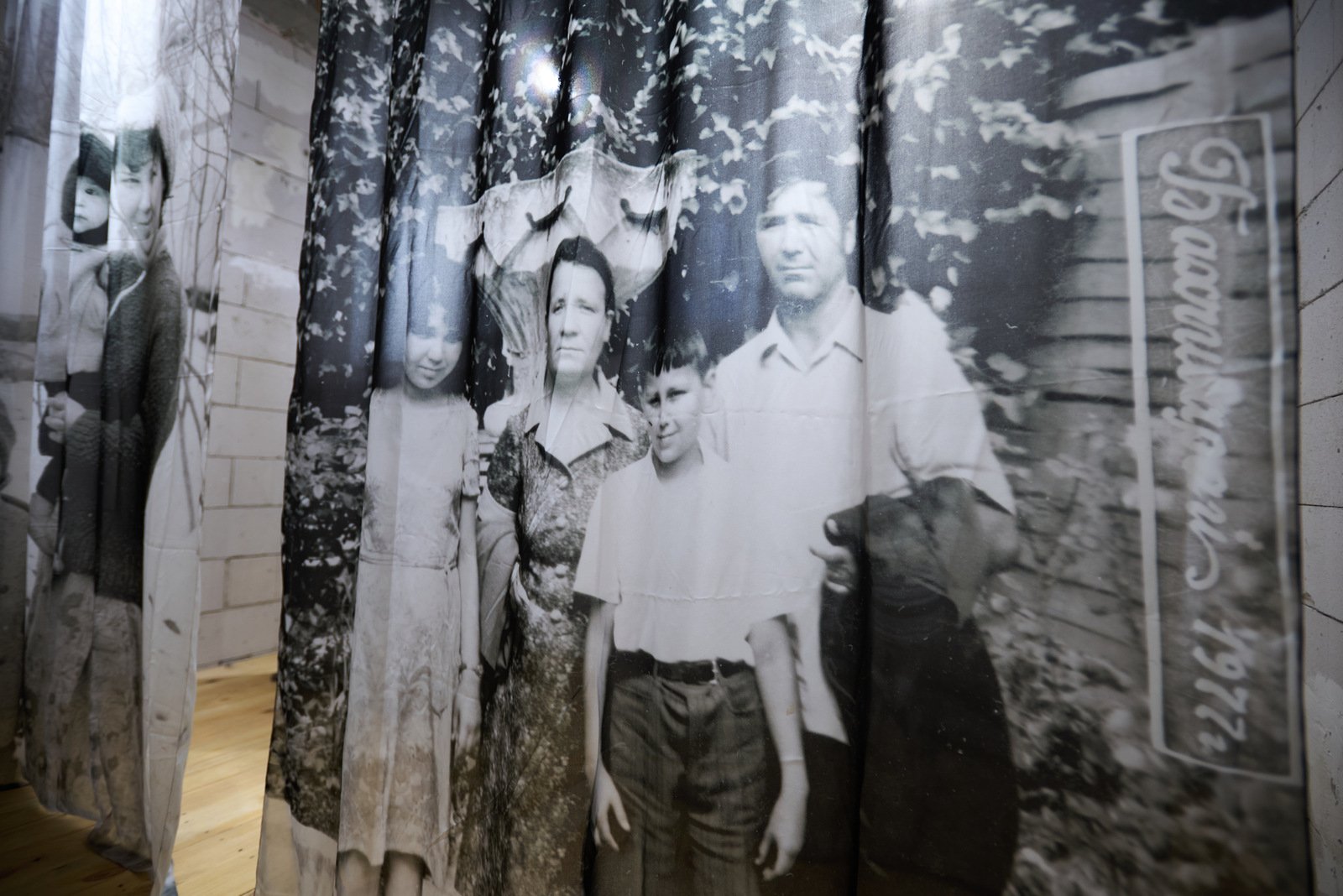

The final work belongs to Emine Ziyatdin – an artist, historian, sociologist, and documentary photographer. During the residency, she created an installation based on a family photo archive which had been miraculously preserved by her grandmother. At a time when most such archives were destroyed during the Soviet era, this collection has become invaluable. She used the oral testimonies recorded with her grandmother and mother, as well as her own photographs, to evoke the passage of time and to reflect on intergenerational trauma amplified by abuses of power.

The work I Am a Daughter of My Father engages both personal and collective history. The title refers to a Crimean Tatar naming tradition where a son or a daughter is identified through the father’s name. In Emine’s video manifesto, the artist reworks this formula and declares: “I am the daughter of the Crimean lands,” symbolically naming the land itself as her parent – a place that carries trauma, violence, family, and love all at once. It also reflects multi-generational roots: from archival photos of her great-grandparents, grandparents, and parents to images of Emine herself, her daughter, and her niece. A central figure is the father – both a bearer of tradition and of traumatic experience for three generations of women in her family: her great-grandfather, who was executed by Soviet forces in 1937; her abusive grandfather; and her own loving father, from whom she has been separated from by borders and full-scale war since 2022.

The photographs are printed on chiffon fabric – a material that imparts ghostliness to the images, like memories that emerge and fade. The installation is complemented by a video manifesto in which the artist proclaims: “I am the daughter of the Crimean steppe, I will remember the victims, perpetrators, and bystanders, I am a mother.” These words embody responsibility not only for the continuation of her lineage but also for the preservation of Crimean Tatar history and traditions.

A lost home persists in memory as fragments and images that gradually mythologize. As scholar Aleida Assmann notes, “what is deeply embedded in memory does not always conform to the norms of reason and empiricism”[2]. The unknown demands filling – with imagination or an alternative story about a place you have never been, yet which shapes your identity. Or it drives the search for facts, without which a “valve” remains – a void that prevents true self-understanding. W. G. Sebald wrote in Austerlitz: “I was constantly occupied with the accumulation of knowledge, which served for me as a kind of compensatory substitute for memory…”[3].

Permanent Home of Displacement is a polyphonic constellation; it is a story of a people through the experiences of different generations, for whom home is loss, searching, memory, or myth.

[1] Kultur Austausch. (2022, July 1). A peninsula in ruins [Review of A peninsula in ruins]. Kulturaustausch; Institut für Auslandsbeziehungen. https://www.kulturaustausch.de/ Author: Oksana Schur. Translated by: Claudia Dathe and Jess Smee https://www.kulturaustausch.de/en/issues/issue-i-2022/a-peninsula-in-ruins/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

[2] Ассман А. Простори часу. Форми та трансформації культурної памʼяті. Київ : Ніка-Центр, 2014. 440 с.

[3] Sebald W. G. Austerlitz. London: Hamish Hamilton, 2001. 415 p.

Artist: Renata Asanova, Sevilâ Nariman-qizi, Yusuf Abibulaiev, Elmira Shemsedinova, Emine Ziyatdin

Curated by: Maria Kulikovska, Dayna Nelson

Exhibition Title: Permanent Home of Displacement

Venue: Garage33, Gallery-Shelter

Place (Country/Location): Kyiv, Ukraine

Dates: 08.08.2025 – 07.09.2025

Photos: Natalka Diachenko