Ewa Borysiewicz

Ewa Borysiewicz: Wojciech, Agnieszka, you’re both on the organising committee for FRINGE Warszawa, an event for artist-run-spaces and grassroot cultural initiatives taking place in the Polish capital since 2022. Would you mind introducing yourselves briefly and telling me what role you play in the organisation?

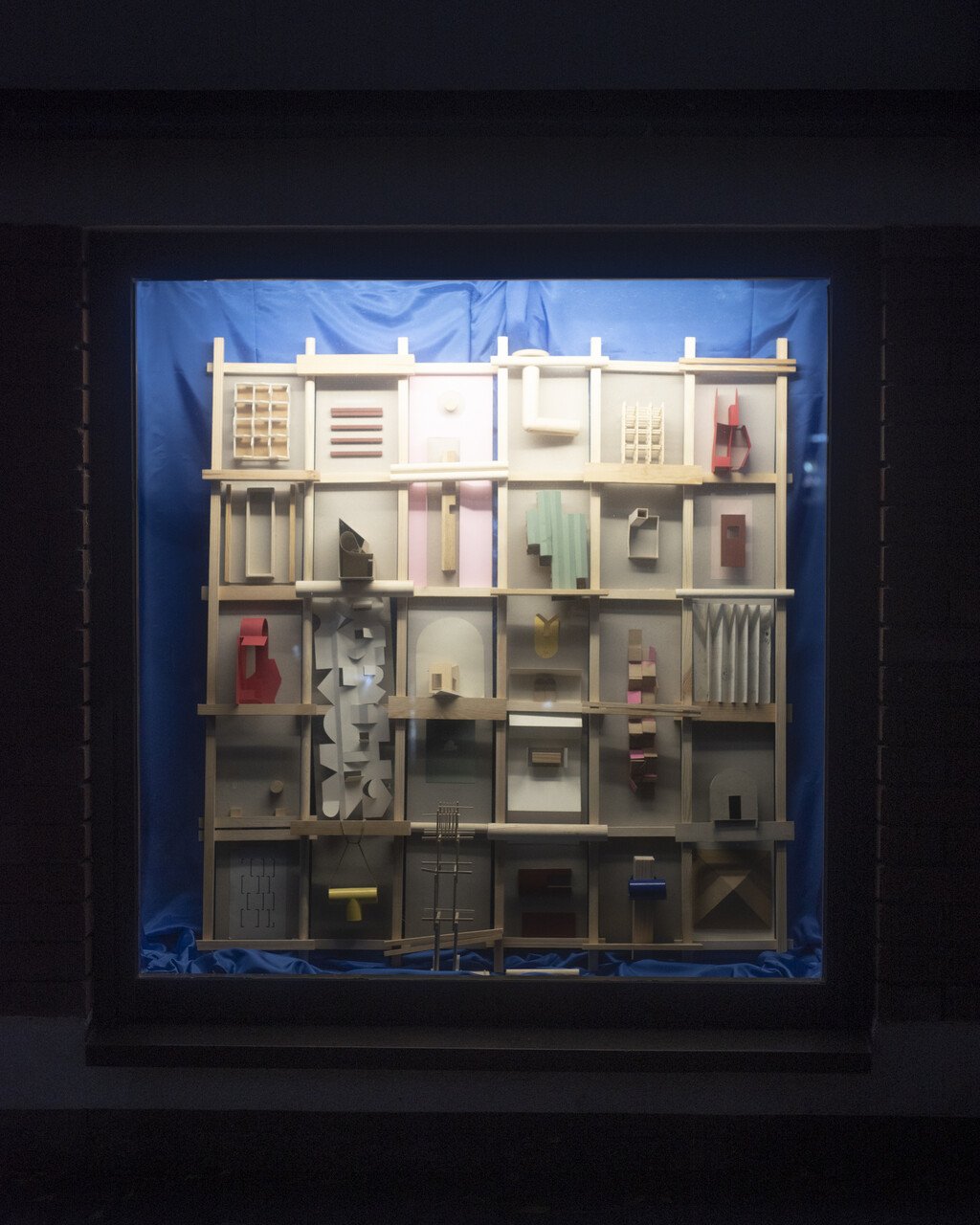

Agnieszka Cieszanowska: I would situate my work at the crossroads of art and design. My medium is mostly textile, ceramic, glass, but I sometimes work with sound and voice in my practice. For the previous editions of FRINGE, I was working as an organizer and curator, both with the Ziemniaki i foundation and Radio Uziemienie, a performative group I am engaged in. For this year’s edition of FRINGE, as well as the previous one, we’re putting together a pop-up show with Tajny Stryszek at the seat of Stowarzyszenie Historyków Sztuki (the Association of Art Historians) in the library of professor Jan Białostocki.

Wojciech Gilewicz: I still think of myself as a painter, but I also work extensively with video, and at the intersections of installation, performance, photography, and, more recently, ceramics. For a couple of years now, I’ve been active in Inne Towarzystwo (Other Society), an artist collective in Warsaw that I co-founded and that organized many exhibitions and other events. Simultaneously, I also run my own Walewska8studio project, which is my art studio where I work but also a place where I sometimes invite other artists to stay. The Instagram profile of Walewska8studio serves as a platform for presenting other artists and my visits to their studios or exhibitions. I see this initiative as a sort of a micro-institution that is my personal contribution to show how diverse Polish art really is.

EB: The organizing committee for FRINGE counts as many as eleven people. I’m very curious how it works practically. I mean, from my experience, it’s sometimes challenging to agree on things when there’s three people involved. So I’m just curious, how do you do it when you’re such a large group?

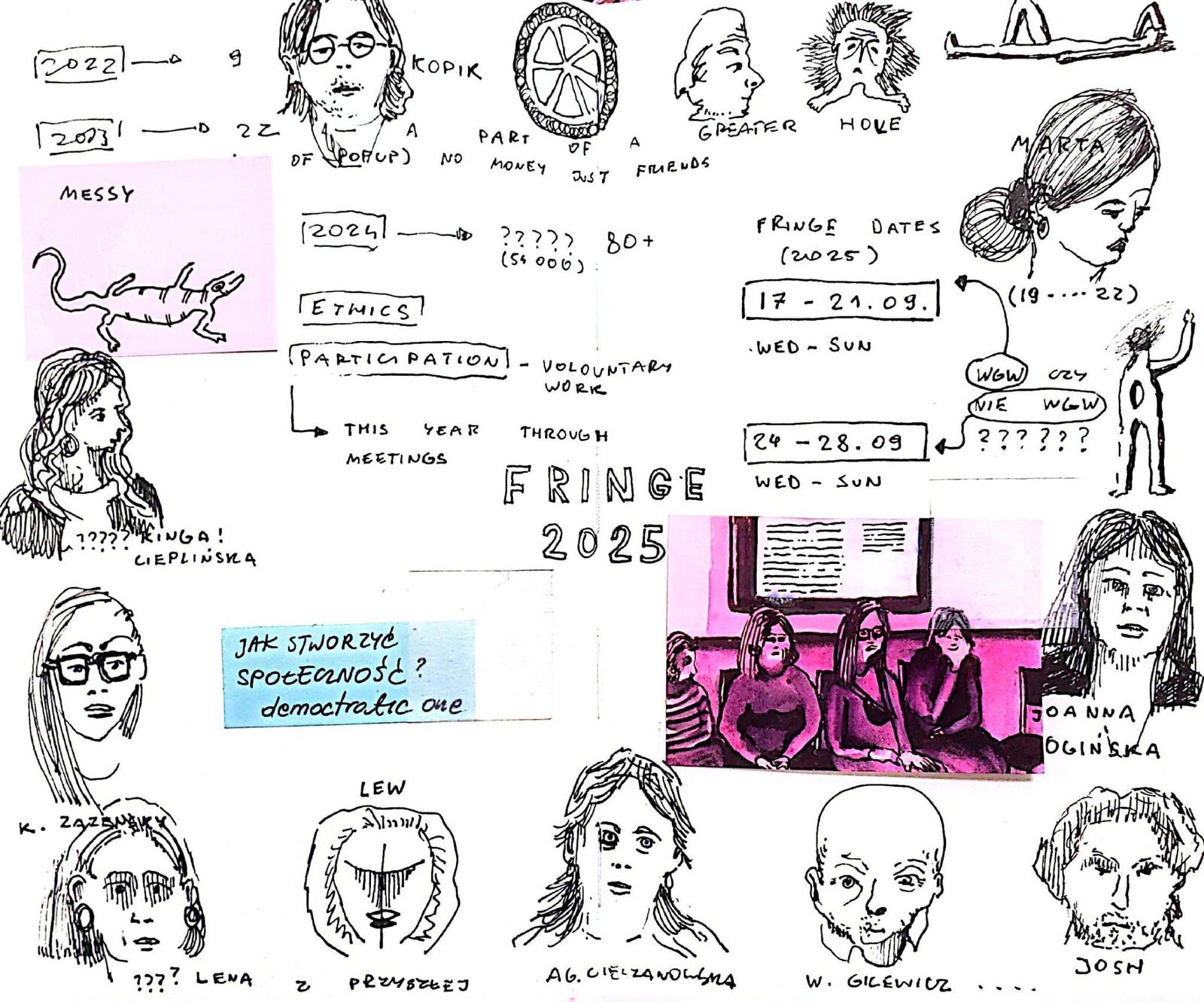

WG: Actually, I think that starting from the last edition, working on FRINGE became more organized, also because it grew significantly. The first two editions were probably more based on our intuition and ad hoc reactivity, as one might say. We were learning. FRINGE Warszawa started with just nine artist-led initiatives. And then, in our second year we were already 22. But in the third edition, so last year, we had four times as many participants. In 2024, we got a grant from the Polish Ministry of Culture, and that was the kind of push we needed to start becoming a more formal, structured team with more complex internal procedures and more efficient ways of operating. This year we received our second grant from the Ministry, and we’re figuring out how to better organize ourselves for this edition. We have different skill sets and areas of expertise, so we complement each other. We don’t carry huge egos and work well as a team with a truly horizontal approach.

AC: I was observing the first edition of FRINGE from a distance; I was still studying in the Netherlands back then. But regarding our structure and the way we organise ourselves, we share a lot of responsibilities but we also have a semi-formal division of tasks, with different roles assigned to the people who feel strongest in those areas.

WG: I remember that maybe a year ago there was a very brief discussion about formalizing – perhaps by creating a foundation or a society – but it was really short-lived. We have remained a very informal group of people, organizing not only a multi-day event but also building the FRINGE community throughout the year. I think it’s a rather interesting development, because the shaping of the organisational structure of FRINGE actually started as a formal requirement – we were applying for the Ministry of Culture grant, and when writing a grant you have to list names and specify roles for each person responsible for a given component of the program.

AC: Yes, I think it also helped us organize, even if at first it felt maybe too formal. For me, it was actually quite liberating to know at least the scope of things I needed to do for FRINGE, and then I could take on and move fluidly between other tasks, since organizing FRINGE is still something we do in addition to our regular occupations. The only institution in a classical sense, helping us organize the event, is Staromiejski Dom Kultury, whose representatives, Kaja Werbanowska, Kinga Cieplińska, and Zuzanna Andruszko, are also a part of the organizational team behind FRINGE. Without them, we’d probably need to set up a legal entity to run FRINGE. But since SDK is eligible for ministerial and city grants and acts as a strategic partner, we’re able to use some of their assets, like accounting for example.

EB: I wanted to ask you about the very beginnings of FRINGE, so 2022, right? I was wondering how this idea came about. Maybe you noticed a kind of gap in Warsaw’s artistic landscape and FRINGE was a way – not necessarily to fill it – but to respond to it in some way?

WG: What’s interesting is that I actually first heard about the initiative through a friend, and then we, as Inne Towarzystwo, were invited by Katie Zazenski to join. My first meeting happened after the first edition and it was at Warszawskie Obserwatorium Kultury (Warsaw Observatory of Culture, an institution that researches contemporary culture in the city), and there I met everyone involved in FRINGE back then and we started talking. I don’t think any of us could have expected that something like this would happen as in the beginning there were only nine people and the general idea was quite straightforward: to do something involving the spaces we represented. As mentioned, I was already part of Inne Towarzystwo back then: there were six of us, and one member had an empty apartment where we started putting on exhibitions. We didn’t really think about structures or protocols, but there was a lot of enthusiasm; the first edition of FRINGE echoed that, it had a similar spirit. However, after two editions, we came to the conclusion that we need to structure ourselves internally, at least to some extent, in order to work smarter and more efficiently.

AC: I also vividly remember that 2022 was still this strange post-Covid time. I had probably already been living in the Netherlands for about two years, so I was more of an observer than really present in the Warsaw scene. But I do recall seeing the poster with those nine spaces and thinking it was something worth keeping track of. At that point, FRINGE still felt like a very loose idea: there was no social media, just independent art spaces coordinating dates for exhibition openings.

For the second edition, because the first one had worked out so nicely, the idea of FRINGE was somehow extended, and it began to naturally grow. Organizing an event together created a shared experience and also shared recognition of the initiates involved. From what I know, everyone that took part in the first edition invited additional spaces to collaborate on the second one. Word spread, the circle extended, and in 2023, FRINGE consisted of 22 spaces. Generally we all know each other, since we function within the same grassroots, non-commercial scene in Warsaw. It’s not such a huge community, even though this year we have more than 90 spaces joining us.

WG: But to answer your question in a broader sense, Covid and that very strange period around it created a real urge to meet in person again and do things together. At the same time, Warsaw’s commercial art scene is highly present and influential – perhaps excessively so – given the extent of its engagement with public institutions and its impact on both programming and permanent collections. A narrative was built – and for a long time prevailed – that the commercial galleries were the ones showing the best work and the best artists, that they were simply “the best,” full stop.

But if one looks closer, one notices that this isn’t necessarily the full picture. The independent sector, and those artists who are not represented by commercial galleries or are not often shown institutionally, are also doing exceptional work. They simply don’t receive the same visibility, as there is no financial interest in promoting their work. The misconception comes partly from the fact that in Poland, opportunities are quite limited and the whole artworld heavily relies on public funding. For example: Warsaw Gallery Weekend, organized by commercial, for-profit galleries, received a generous three-year grant from the Ministry of Culture. FRINGE, as a non-profit initiative, got just a one-year grant this year. In Poland, we’re all chasing the same public money, whether you’re in the art business or not. The artworld is also relatively small in Warsaw. Moreover, the Polish art scene is very centralized, which makes it easy to assume that there is one single modus operandi, be it for a gallery or for an artist-run space. Poland and Polish society is very neoliberal in this sense: we all strive for success and we compete a lot, not always in a fair way. In reality, one needs to look beyond all that and try to change this narrative we all bought into. What I really appreciate about FRINGE is that it’s an initiative led by relatively young people, and it challenges those perceptions with a fresh view on things while creating space for something different, a more complex, inclusive, and nuanced picture of the Warsaw art scene.

EB: From what you say, it’s really a question of visibility. During the time when the Law and Justice Party was in power, and the directors of public institutions were right-wing nominees, those institutions failed to present compelling programs, to say the least. They lost the credibility and confidence of their audiences. What remained meaningful was mainly the exhibition program of commercial galleries. FRINGE, as I understand it, acts also as a balance to that, proving that there are other equally compelling and significant positions that deserve recognition.

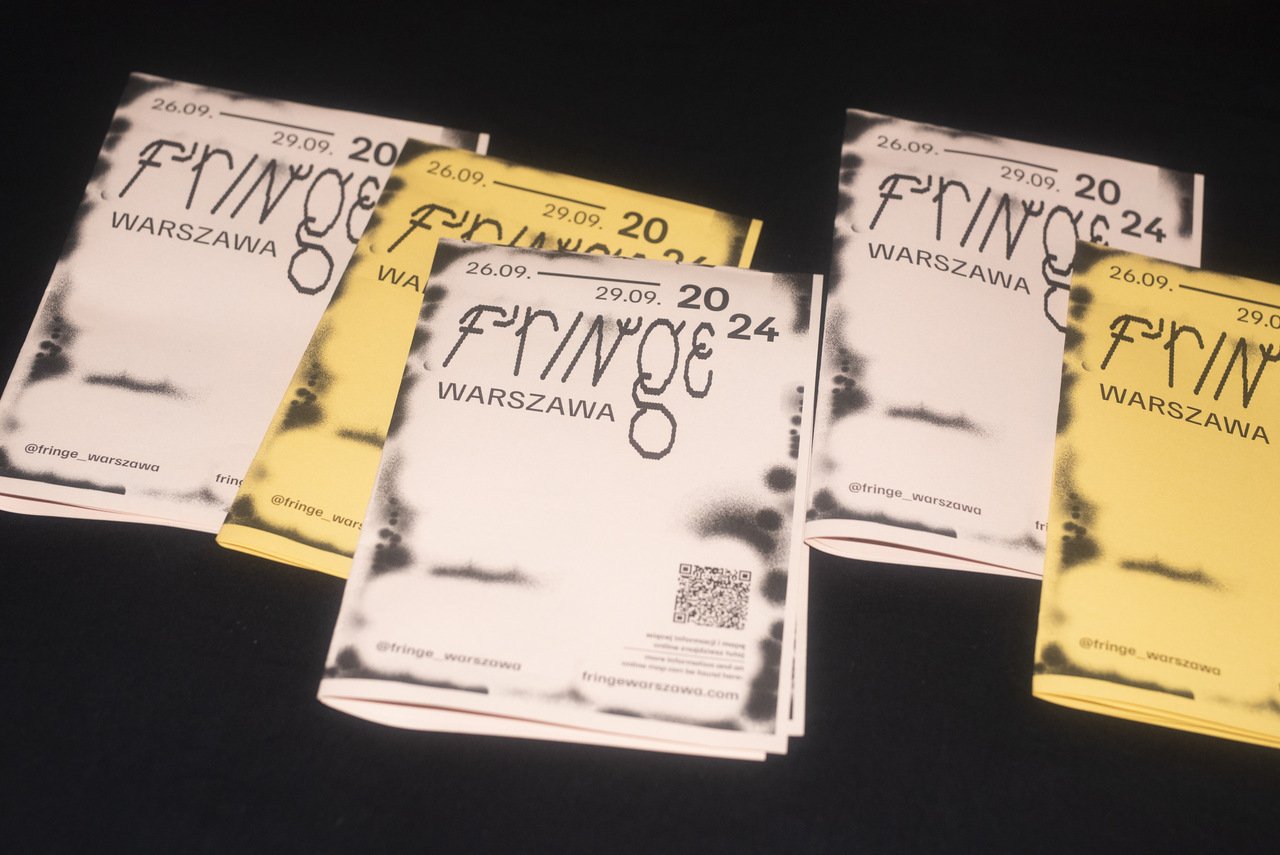

WG: I think this balance between commercial, public, and independent entities is necessary to fully understand the art scene in Warsaw. It is a complex ecosystem: all forms and ways of operating should be present and nurtured. We should not fight amongst each other and exclude. FRINGE does exactly that, because what is perhaps worth noting as well is that FRINGE is essentially an umbrella initiative. We don’t provide anyone with a space, but we do offer the platform for presentation with a common visual identification and, in the last two editions, some production grants. The number of participants in this edition is truly incredible. It really shows how strong the independent sector in the city is. And how much it is overlooked and ignored. Often, all it needs is just a little support – a small push, some interest, a simple “I see you.” This FRINGE “umbrella” brings this independent scene into view, even if it’s modest in scale.

EB: You described FRINGE as an umbrella, so how do you decide who comes under it, who gets to take part?

AC: Since last year, we’ve been operating through an open call, and basically anyone who meets the criteria can join. There are no aesthetic or formal requirements – we have an ethical map, and the main condition is simply to be non-commercial. This year, we added an emphasis on community building; since the spring we began organizing public meetings for the independent art scene. So FRINGE participants had to show up and join the discussions, share their thoughts. Even with that extra requirement, the number of participants is still impressive.

The goal was to encourage active participation, because we felt it was important to have a broader discussion about how FRINGE should function and where it should go. We want participants themselves to be part of the decision-making. Last year, many of the decisions were still made mostly by the organizing team, and there was a stronger sense of hierarchy between the organizers and the participants. This year, we wanted to open that process to everyone involved. Of course, that also means building trust – and trust comes from actually showing up and engaging.

EB: Your whole organizational model seems to me quite unique. Apart from having an open call, you also offer mini-grants, and if I’m not mistaken, you allocate them by random selection. Personally, I’ve never encountered a grant distributed purely by chance. Perhaps it’s the fairest way.

AC: Maybe the reasoning behind this method is worth explaining. It’s always the most important question for us to start with: how do we make it fair? A significant part of the ministerial grant was allocated specifically to support the production of the shows. To avoid spreading the money too thin, we decided to distribute the funds among 35 participants – almost half of the total number of spaces involved in 2024. We wanted each grant to be substantial enough to actually help people produce something – if we divided it among everyone, it wouldn’t have made much sense. In the end, we couldn’t find a better solution than simply doing a random draw. Last year we introduced a small modification: spaces got more chances depending on how many times they had already participated in FRINGE (because there was no money for any of the work of the organizers and in fact, everyone paid for the costs of the designers from their own pockets). We have since dropped this rule, so now everyone – even newcomers – has an equal chance.

WG: I’m even a bit hesitant to use the term “open call” in the case of FRINGE because, you know, usually when you hear “open call” you imagine a jury making selections. But for us, it’s different; we’re not judging anyone. Almost everyone who applies gets accepted. I don’t know what the exact percentage is this year, but the majority of the applications were successful. What we are strict about is supporting only non-commercial spaces, and that’s really the main criteria, so we check for that. Sometimes, at a later stage, a few initiatives don’t end up being included, usually because of problems with finding a physical space. But that’s it.

AC: Yeah, sometimes people just can’t find a space, so obviously they have to resign because they can’t meet the formal requirement of having one. But this is actually super crucial for FRINGE – that we don’t curate who is exhibiting. It’s open to any space that creates something in line with the ethical values we share. At the same time, this is an ongoing conversation we keep revisiting: what does it really mean to be grassroots or non-commercial? Can you sell the work, or not? For example, many commercial galleries in Poland also operate as foundations: so does that make them grassroots, or not? These are the kinds of questions we still don’t have a final answer to, and I think every year we’ll have to come back to them.

For now, we mostly base it on trust. We say what FRINGE is, and we hope the people who join – and I think this has been working – are aligned with that idea.

EB: I’d like to return for a moment to the community meetings and the year-long participative process before FRINGE. What kinds of insights came out of those meetings? Were there particular issues that were most debated or questioned? What are the main challenges or hopes of the independent art community?

WG: Perhaps it would be good to explain why we opted for organising these community meetings: at a certain point, we realized that in addition to FRINGE being an event taking place in September, it is also a group of people, a network of people engaged in similar activities. And we decided that the best way to refocus on this was simply to gather: either in person or online.

AC: Yeah, it’s a bit hard to sum up, because now I’m revisiting all the meetings we’ve had… There were around five or six so far. A lot of them were quite practical, mainly about passing on information, to clear any questions or issues in regards to the application procedure, etc. But beyond that, many topics gave us a sense of what people actually need and what they want from FRINGE, outside of what the organizing team imagines. For example, in the last community meeting, we were deciding whether we should have a party – it may sound simple, but was a crucial issue to understand the needs of the independent art community in the city. We also discussed whether we want collaborations with different external partners, how we feel about the opportunities they bring, and what kind of activities they propose.

WG: The dates of the 2025 edition – this year FRINGE will not take place at the same time as Warsaw Gallery Weekend – was also decided through the community meeting, not just by the eleven people in the organizing team. That was quite an intense discussion we were having about that, but I would not call it an argument, just a lively conversation.

Another big topic was the number of spaces that we should include. I remember after last year’s edition we were all quite exhausted, and during the meeting wrapping up FRINGE 2024, we even said that maybe next time the event should be more compact – like 40 spaces, half of what we had. But in the end, that didn’t happen; in fact, this year we have even more participants than last year. That started a bigger discussion about how much work we can realistically take on. As Agnieszka mentioned, we all have our own jobs and lives – no one is fully dedicated to organizing FRINGE. So the question becomes: how much work can each of us carry, and how many new things can we take on for FRINGE? It’s really about finding balance.

EB: Apart from the basic principle that the participating spaces should not be commercial, what other ethical guidelines do you have?

AC: We knew that Warszawskie Obserwatorium Kultury was operating with an ethical map and so we looked to them for inspiration, some of our points actually came directly from them. The idea is really to balance artistic freedom and diversity – which we definitely want in the FRINGE community – with a sense of care and shared values. The guidelines might seem pretty general, but they still serve an important purpose. Like you said, one of the main ones is that the spaces should be grassroots and non-commercial, often working in some kind of collective way.

Others are a bit more specific – for example, we don’t want any promotion of violence, and we try to be as open as possible to different audiences. This year we also made some changes within the organizing team, like adding accessibility info on the map for people with mobility impairments. And we try every year to expand inclusivity – like organizing tours in different languages. And of course, FRINGE operates in both Polish and English.

EB: What can you tell me about this year’s programme? Is there perhaps a theme emerging? Or a tendency you noticed amongst the proposals?

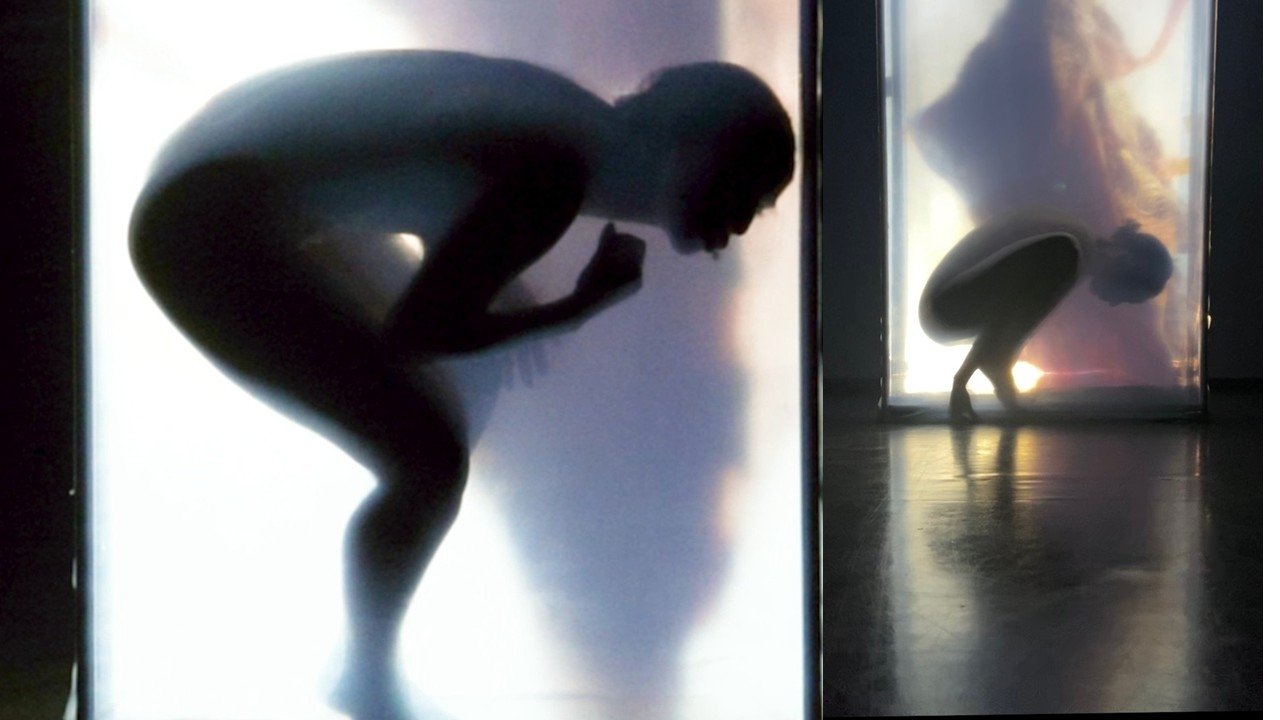

WG: I am not sure if we really have yet a general sense of what’s going to be presented across all – almost 100 – spaces this year. Our goal is to provide visibility and create interest. I can say more about the performative part, because this year it’s a separate section from the main program. It’s happening at the Warszawskie Obswerwatorium Kultury (WOK), so in the very center of the city, and it’s organized so that every evening, there will be two performances over four days, eight in total, selected by Alka Nauman, Grzegorz Borkowski, and myself. This is actually the only curated part of FRINGE. The three of us put together a broad selection that shows the diversity of independent performance today, and I’m sure it will give people an interesting glimpse into the field.

AC: This year we’ll host a series of guided tours as we did last year: for example curatorial tours and walks with Wielozmysły designed to include people with visual impairments. This year we will also offer tours prepared in collaboration with students from the Faculty of Artistic Research and Curatorial Studies at the Academy of Fine Arts. We’re really glad that we have the opportunity to engage the student community. But to kick things off, on Wednesday, September 24th, we’ll host the FRINGE community at WOK, with soft drinks and silkscreen printing, and finally a party during FRINGE on Saturday, September 27th at Bar Studio. The full programme will be published very soon on our website.

EB: For my last question, I’d like to ask something quite broad, but I think it’s worth answering, especially for readers who may not be familiar with the situation in Warsaw. What does it feel like for you at this moment, and how was it when you first started working with FRINGE? Would you say that a certain shift happened and if yes, how would you describe that shift?

WG: I think it’s definitely more diverse now. I mean art happening beyond the commercial and institutional contexts is more noticed throughout the year in the city. Just two weeks ago, for example, I went to two openings – one in a commercial gallery and one in an independent space – and at both of them people were talking about… FRINGE. Everyone’s already waiting for it, coordinating, organizing, discussing, and for me that’s really exciting. FRINGE feels like something that was lacking all these years. Usually we just work in our own studios and spaces. We have friends and connections, but often it’s more about focusing on our own careers, our own exhibitions. FRINGE shows that the real strength and the biggest possibilities actually come from doing things together, from sharing and from self-organizing. It creates something we have in common and something that we care about – something not solely driven by money, fame, and success.

EB: So not competition, but cooperation.

WG: Yeah, exactly. It’s really important, as you said, that it’s not a competition. Even from the very beginning, with the call for participation, it’s not about selection – it’s simply about registering and saying, “Okay, I’ll have an exhibition, I’ll find a space, and I want to be part of FRINGE and I adhere to your values.” And what’s especially interesting for me is that it’s not only about the younger generation of artists. At our community meetings, you can see all generations coming together, which is really amazing. And uplifting. Everyone has their own place within FRINGE.

AC: It really brings people together and that’s the main idea behind it. I’m also really grateful that so many young artists – for example, those just graduating or right after graduation – are joining. But what’s equally exciting are the surprises that come every year with FRINGE, seeing who actually wants to be part of it. There are archive studios, or people you might usually think of more as craft or creative makers, who are in fact doing amazing visual art. And that’s the beauty of it.

EB: And how has the artistic landscape in Warsaw changed? I was wondering how you see those changes since you joined FRINGE. Because Wojciech mentioned it’s become more diverse – I understand you mean diverse in terms of a wider range of ways to operate, with more possibilities for self-organizing and working through different kinds of organizations, so that there’s greater plurality.

AC: Yeah, I agree with Wojciech on this. But I’d like to come back to the notion of collaboration instead of competition. We don’t even really call it a participation process in FRINGE – it’s more like an open invitation, not an open call. Because, as we’ve discussed, there’s this tiredness around open calls, around curation, competition, and all these very rigid, formal rules. And also how that creates this strong individualism in our scene, this competitiveness. What I hope, and what I think makes FRINGE work so well, is that it’s based more on sharing – on saying, “Let’s do this together.” So I think that’s a positive change that’s happening. And it also connects to what you, Ewa, were saying earlier – about the distrust in institutions, and how Covid pushed us to form these smaller groups that we now operate within. And in today’s neoliberal climate, collaboration isn’t exactly encouraged. Everyone is mostly out for themselves, competing for resources like grants, sponsors, and so on. So it becomes very difficult to maintain a real sense of community and collaboration in that environment.

There was actually a big need voiced during the community meetings about how to create a space for exchange and sharing resources. What we have now is really just a starting point, a small step. For example, we set up a very basic Excel sheet with offers and proposals – who’s looking for what, who can provide something. It’s a simple tool, but it already helps us support each other and exchange knowledge and resources within the scene.

EB: FRINGE sounds almost utopian at times.

WG: We never say it out loud, but it sometimes does! In the neoliberal, accelerated capitalist framework it feels impossible that people will collaborate, work together, share everything, and actually be happy doing it. And yet, somehow, it’s happening, and it will continue to happen: after we finished the third edition last year, just a couple of weeks later we were already talking about the next one. And it’ll probably be the same this year – once we wrap everything up, we’ll evaluate and start thinking ahead.