Arash Shahali

It is the morning after this year’s summer solstice and I am making my way from Hamburg’s main train station to the Aby Warburg Haus, joined by a Serbian art critic, a Mexican artist, and a Siberian astrologer. As a Belgo-Iranian art worker on assignment, I get to complete our multinational four-leaf clover. Together, we are to attend a daylong symposium on planetary thinking as part of the public programming around a newly-opened art exhibition; a scene all too familiar to those who stopped worrying and learned to love contemporary art openings. While the train takes us to Hamburg’s more upscale environs, we discuss the US’ entry into the Israel-Iran conflict with the regrettable bombings of the Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan nuclear facilities, which had taken place just before sunrise and threatened to destabilize the surrounding regions. Somewhat in keeping with the themes I imagine will be explored in the symposium, I remark upon the fortuitous timing of these attacks, which happen to have coincided with the night of the summer solstice. The astrologer informs me that this timing is no coincidence, however. The date was consciously and carefully chosen to harness the heightened energy that celestial events like the summer solstice are typically rife with. They go on to name Operation Barbarossa – the devastating invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany, which took place on June 22,1941 – as a comparable example.

Armies – I am told – still have astrologers in their employ with whom they divine the most auspicious day to execute attacks. Countries are even said to have birth charts, established by examining planetary placements on the day a given nation is founded. This could explain the role various countries, governments, and regimes have played in past geopolitical conflicts and – perhaps – predict their involvement in future ones. It’s a view on international warfare and geopolitics that I believed had gone out of style with Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein, the 17th century Bohemian military leader whose reliance on astrology to predict strategic successes was so well-known, it made its way into Friedrich Schiller’s dramatic trilogy Wallenstein 150 years later. Von Wallenstein’s assassination – ironically enough semi-predicted by his reluctant astrologer Johannes Kepler – seemed to end the millennia-long practice of mixing military campaigns with planetary alignments.[1]

Now, I do not begrudge my astrologer colleague[2] – or anyone who dabbles in tarot, alchemy, palm reading or planetary conjecture – their belief system. In times of crisis, magic and occultism seem better suited than reason to navigate the often contradictory and emotionally-fraught complexities of events unfolding on both a personal and a global scale. Apps like Co-Star, Sanctuary, and The Pattern make access to horoscopes, tarot readings, and magic spells easier than ever, to a rapidly growing user base that seeks to make sense of a world appearing bereft of logic, purpose, and fairness. However, I fear that applying esoteric practices directly onto politics, international relations, and (genocidal) violence risks stripping the various involved parties of their accountability and – in a sense – their agency. Then again, as a triple Earth sign I would think that, wouldn’t I?

I couldn’t help but wonder if art can perhaps function as a more appropriate conduit to explore the role the occult can play in analyzing historical events, power structures, struggles for liberation, and systems of order and chaos. Mysticism and astrology, after all, has been woven into artistic practice since determined individuals painted what are believed to be star maps and zodiac signs on the walls of the Lascaux cave system. It’s with this mindset that I find myself on another train a week later, this time to Salzburg – with the aim of catching Mikołaj Sobczak’s solo exhibition Moon, Sun, Mercury at Salzburger Kunstverein. “If countries can have birth charts, what about artworks or exhibitions?” I muse as the landscape switches from Viennese hilly to Salzburgian rocky. Moon, Sun, Mercury – in any case – seems poised to provide possible answers to my queries. Its title can be understood as a reference to one of the most critical conjunctions in Vedic astrology. The rare alignment of these three heavenly bodies is said to enhance the combined energies of ego, emotion, and intelligence. The sun represents the ego, and orients itself towards the future through sheer vitality. Emotions are the domain of the moon, ruling over the subconscious, which houses past experiences, beliefs, and memories. Mercury informs the way we think, and can bridge past and future through systems of cognition.

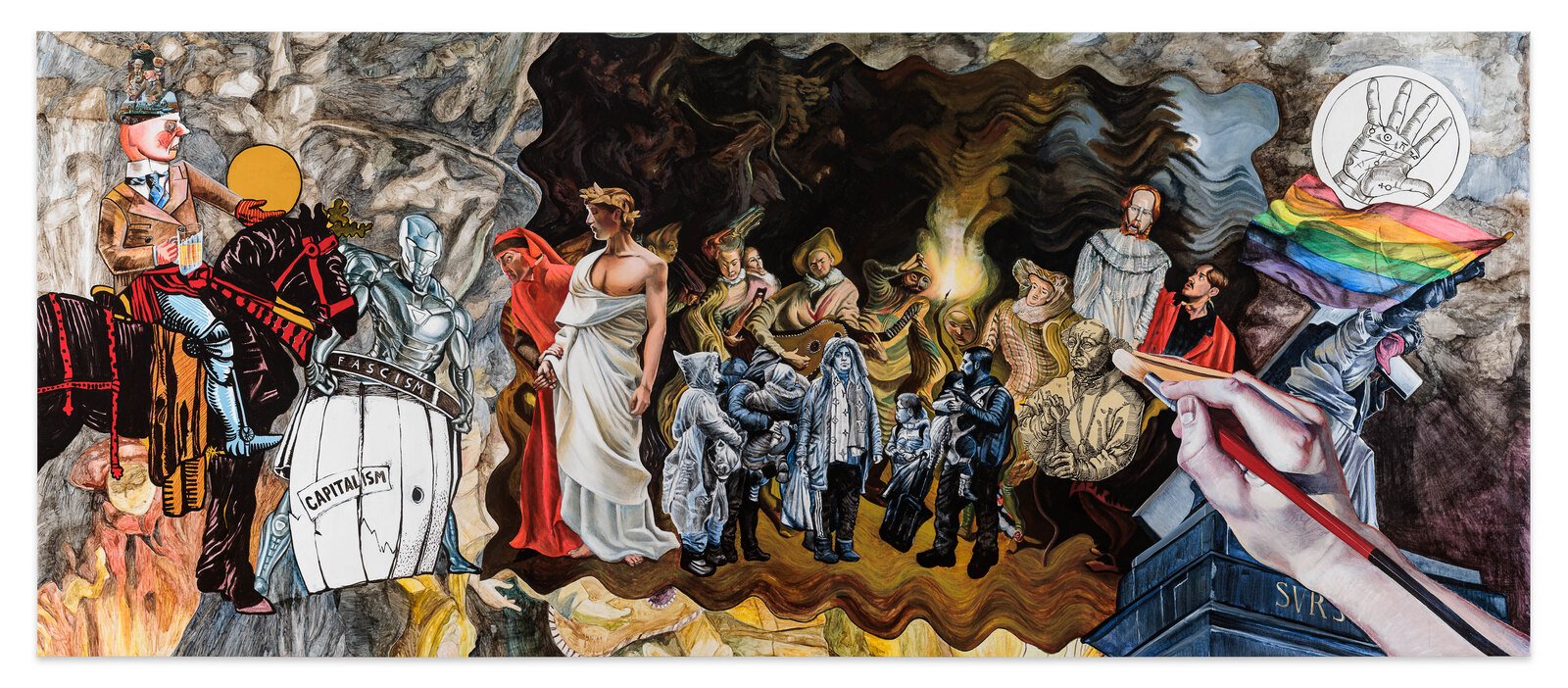

Sobczak’s presentation consists of three newly commissioned large-scale paintings, elegantly suspended from the ceiling of Salzburger Kunstverein’s Grand Hall. Thematically, they reflect the ternary constellation from which the exhibition borrows its name. Aptly titled, Moon (Propaganda), Sun (Magical Realism), and Mercury (Underground) – Moon, Sun, and Mercury for short – the paintings bring together a number of historical and contemporary queer activists, revolutionary figures, outcasts and countercultural thinkers into a constellation of archetypes, like the hero, the activist, the jester, or the healer. They appear in cleverly choreographed proximity to more antagonistic archetypes, which range from monstrous interpretations of our current era’s tech-oligarchy to grotesque personifications of capitalism and fascism itself. By assembling these disparate characters onto the grand canvas typically reserved for historical tableaus, Mikołaj Sobczak exposes (oft-untold) narratives of survival and resistance in the face of absolute power.

Standing in the doorway of the Grand Hall, my gaze is pulled in all directions: Sobczak’s cast of many is brought to life through a consciously disorienting blend of visual styles, ranging from archival materials, cartography, historical portraiture, and communist posters to occult imagery, tarot cards, and caricature. These elements unfurl across the three canvases in a frenzy; and not seldom do they find themselves embroiled in conflict. It’s a feverish staging of queer histories that is at once colorful, campy, fractured, unruly, tender, harsh, resilient, and in perpetual motion. This is echoed – cleverly I might add – in the way the paintings are installed: askew, afloat, and purposefully defiant in their refusal to align themselves with the surrounding walls. Two of the three paintings – Mercury and Sun – directly greet the visitor, while Moon faces away, perhaps evoking a card yet unturned? The placement of the works reveals an engagement with the exhibition’s esoteric and holistic underpinnings so thoughtful that it can only be the result of curational divination. Mirela Baciak, artistic director of Salzburger Kunstverein and curator of Moon, Sun, Mercury, concedes as much when I meet her the day prior to my visit. As I diligently pet her dog Neptunia, I am made aware of the efforts made to match the execution to the content. In a move worthy of Wallenstein himself, Baciak even moved the exhibition dates from 2024 to the more auspicious 2025 after consulting an astrologer. Exhibitions – it would seem – do have birth charts.

Keeping all of this in mind, I’m conscious of how my own body approaches the constellation of art works, how it becomes a part of Moon, Sun, Mercury’s carefully staged choreography; it’s a welcome opportunity to think of my body as celestial, rather than slovenly and unkempt which I commonly use to describe myself. Sensing a gravitational pull to that which is concealed, Moon – I decide – will be my point of entry into Sobczak’s take on historical painting. After all, what better way to approach the future than through an understanding of the past? Perhaps the darkest of the three works, both in tone and subject matter, Moon hosts a rogues’ gallery of propagandist archetypes from past and present. The gathering is an uneasy one: the figures assembled here are at odds. Tensely sizing each other up, they appear to be preparing for the imminent showdown between propagandist imagery of oppression and the visual language of resistance.

Capitalism’s final boss takes form in a mutated version of one of the caricatures from George Grosz’s painting Pillars of Society (1926). Hoisted upon his horse, this grizzly “Knight of Capitalism” enters the painting, moon in one hand, Weißbier in the other. The swastika that had adorned his tie in the original painting, has been updated for our times with the logo of X (formerly Twitter). It’s a flimsy re-brand that barely conceals the fact that today’s tech-oligarchy knows very well on which side of the political spectrum their bread is buttered. Next to him, a buff and shiny figure, reminiscent of the Silver Surfer, attempts to salvage a broken barrel of “capitalism” by adding a ring that says “fascism.” Not unlike his namesake in the Fantastic Four comics, he heralds impending annihilation with little subtlety. In opposition to these frantic supervillains, Sobczak places holistic thinkers like Paracelsus, Dante Alighieri, and the occultist writer Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, the latter of whom is represented by a hand marked with celestial signs, alluding to Agrippa’s penchant for palmistry as a means of understanding present and future. All three of them – in their own way – resisted and challenged the dominant power structures of their time through alchemy, poetry, (pseudo)science, art, and embodied forms of knowing. Joining them in the fight is Sobczak himself, wielding a paintbrush as the weapon of choice. In a callback to his 2023 performance Lutzi Puppe Wutzi, the artist is accompanied by a life-sized ventriloquist doll of the delightfully foppish Archduke Ludwig Viktor, whose close familial ties to the Austrian imperial family allowed him to more or less live life as an openly queer 19th century man; an existence not easily afforded to Luziwuzi’s lower-ranking contemporaries – and to many of us today, for that matter.

At the center of the chaotic assembly of opposing forces, Sobczak places Ukrainian refugees amassing alongside the Polish and Belarusian borders. Their prominent positioning does little to conceal their displacement. Perhaps the most human of all of the figures gathered in Moon, they remind us of the very real outcome of propagandist strategies; violence, oppression, forced relocation, and – ultimately – death. Sobczak portrays these refugees here as living individuals of flesh and blood, rather than numbers in graphs used for political posturing, or the avatars of misery we bemoan when scrolling past news-reels. Moon in a way offers these people a home, a place in history. Within the dimensions of the canvas, they get to remain in limbo; their fates dependent on how the surrounding boss battle plays out.

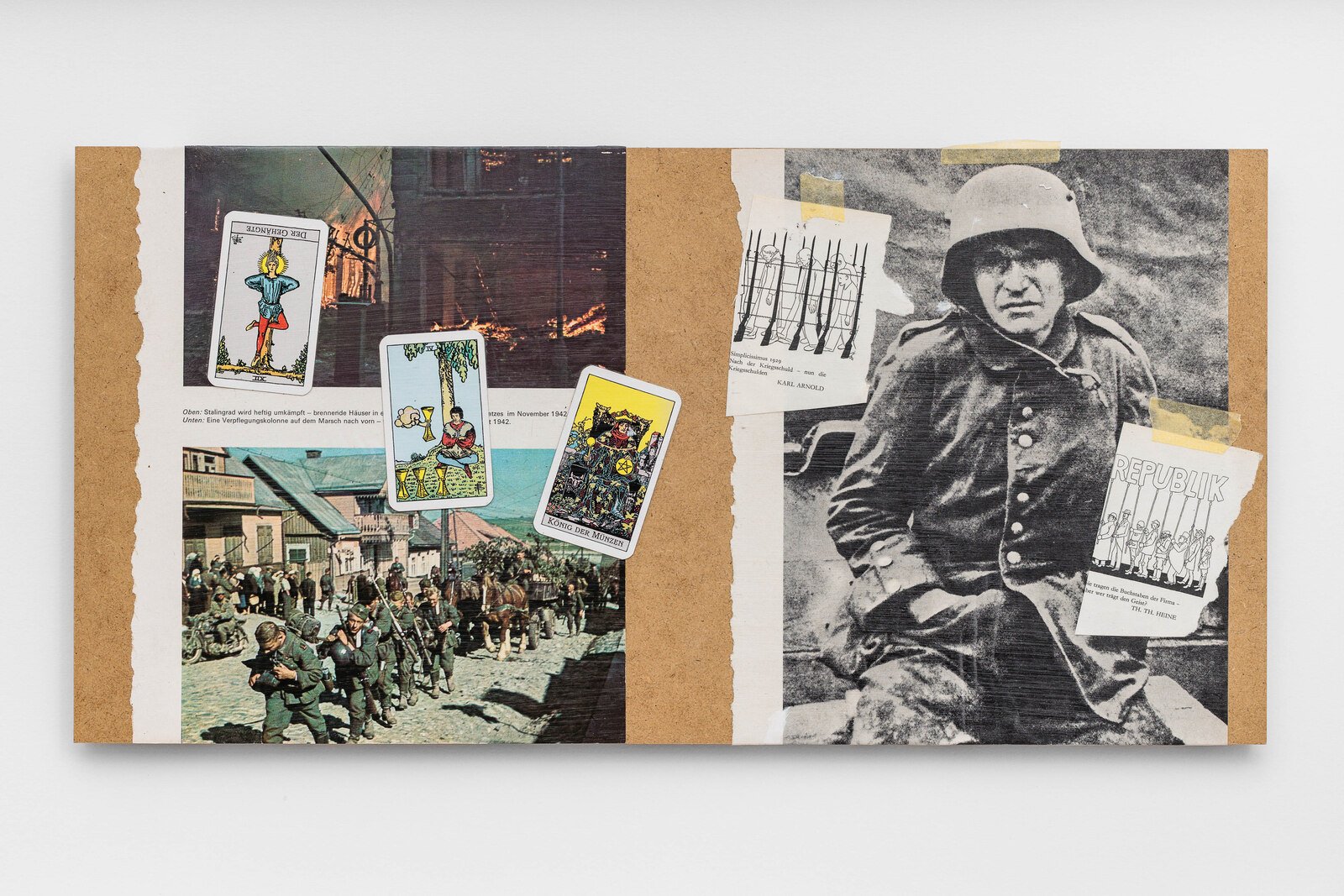

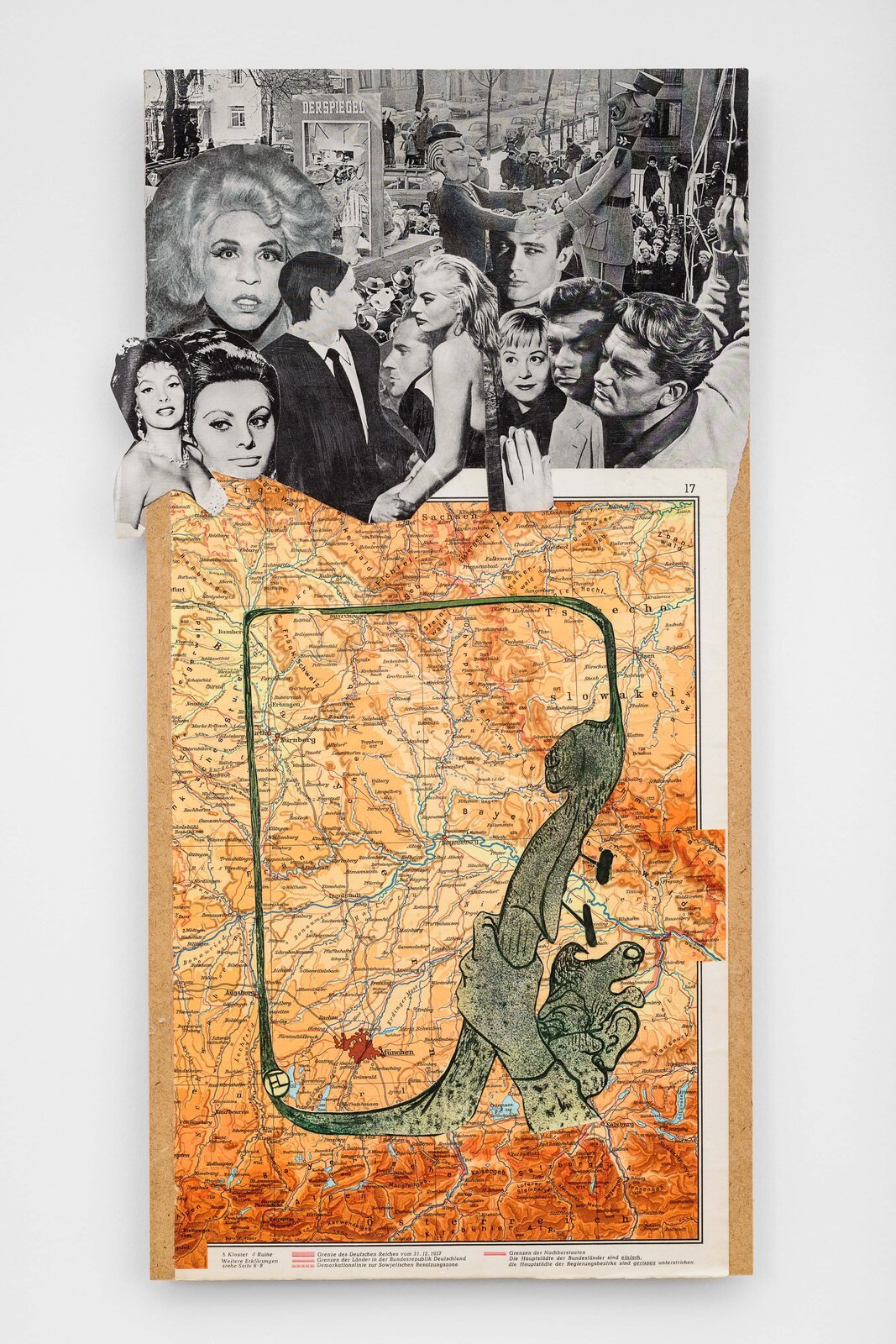

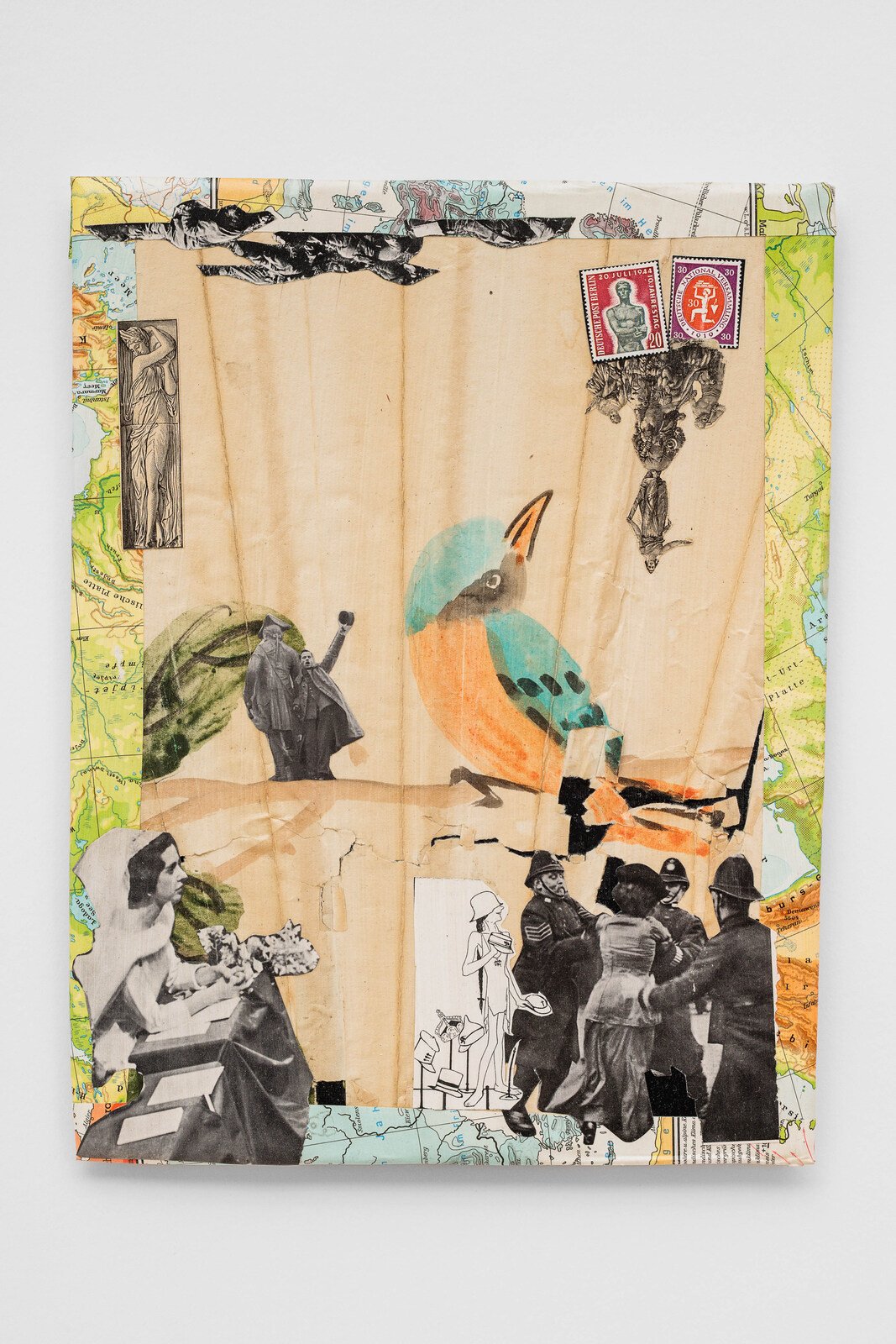

Somewhat eager to be released of Moon’s grim delirium, I continue onwards in my celestial trajectory through the Grand Hall. Attached to the backside of Moon’s canvas, I find the first of a series of collages that the exhibition brochure refers to as footnotes. These footnotes are composed of materials that Sobczak found on the way from his apartment to the studio. Does their serendipitous placement on the artist’s path denote subliminal messaging on the part of the Universe? Codes for him to decipher and be guided by, perhaps? On a smaller scale, the footnotes echo the ideas, timelines, and iconographies that are present in the larger paintings, while also imbuing Moon, Sun, Mercury with a sense of intimacy. A personal touch. Installed in two opposing corners of the space, as well as on the backside of Moon and Mercury, these collages trace a diagonal line through the constellation of the three larger paintings; a very queer way of intersecting indeed.

According to writer and theorist Sara Ahmed, the queer diagonal slant characterizes the daily negotiation “with the perceptions of others, with the straightening devices and the violence that might follow when such perceptions congeal into social forms.”[3] As I move along this slant, from Moon past the backside of Sun, towards Mercury, the collages take me through a history queered by a subconscious interpretation of found materials: bodies engaged in sports, science, war, and entertainment find themselves woven into images of the battle of Stalingrad, maps of past and present German territories, an article on Kennedy’s assassination, cards from the Rider-Waite tarot deck, lascivious orientalism embodied by Rudolph Valentino in a production still of The Sheikh (1921), and publicity nudes of Josephine Baker. It’s a telling of history that runs diagonally, folding in women’s suffrage activists detained by police officers and queer icons like Vaginal Davis, James Dean, and Marlon Brando, for good measure. The collages have a delightful conspiratorial quality to them, somewhat abated by the absence of the red thread that typically connects these kinds of images in filmic portrayals of conspiracy theorists.

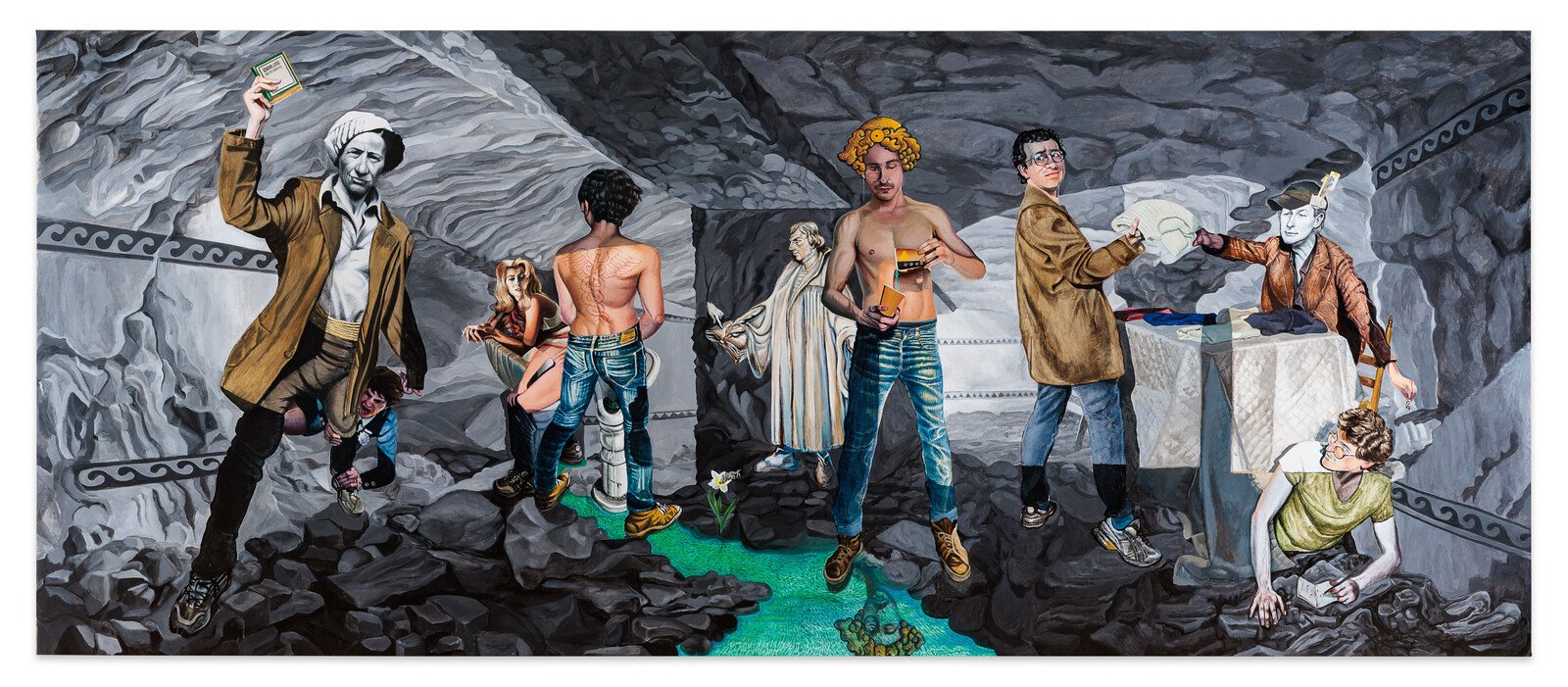

Having arrived at Mercury by way of Sobczak’s footnotes, I get to catch my bearings. This painting’s temperature is cooler, the canvas less crowded. Set in what appears to be an underground bunker, activists, writers, and artists get some room to untangle themselves from dominant power structures and explore and preserve alternate forms of knowledge. This untangling is not just philosophical; lesbian author Eve Adams is quite literally shown trying to free herself from the clutches of an undercover agent. In Mercury,her struggle remains in perpetual suspension: as a viewer, one can’t help but hope she manages to break free. In real life, however, Adams was not so lucky: her arrest by the officer put into motion her deportation from the US during WWII, which ultimately led to her death in Auschwitz.

Mercury explores how knowledge can resist surveillance and combat erasure. Eve Adams, after all, is portrayed with her book Lesbian Love. This publication’s enduring status as the first known lesbian fiction novel, proves that ideas can persevere despite efforts to censor and eliminate. The painting suggests that this type of knowledge is fluid, mutable, and forever in motion through the inclusion of a stream welling from the back of the bunker. It trickles past figures like Catherine Deneuve and a ghostly Martin Luther, towards the viewer, doubling as a free-flowing metaphor not only for knowledge, but also for ideas around bodily autonomy. Fluids such as sweat, semen, tears, piss, and blood continuously find themselves the subject of societal handwringing, stringent ritualization, and rigorously enforced sanitization. This aversion can lead to situations wherein such fluids can be used as excuses to divide and categorize people, such as the ancient four temperament theory (where personality was determined by the prevalence of certain fluids in the body) or can become tools to discredit or valorize others; think of the way that menstrual blood has historically been considered poisonous and able to rot food and drink, or how fascists idolize bloodletting only when it takes place on the battlefield.

The stream in Sobczak’s Mercury resists such notions, showing that what is fluid continually circumvents the powers that seek to control its flow. More often than not, the unbridled perseverance of thought, dignity, and kindness carries in itself a quiet form of heroism. Knowledge of how to evade the authorities allowed Polish queer activist Stanisław Chmielewski to smuggle countless Jews out of the Warsaw Ghetto during the Nazi-occupation of Poland. Chmielewski, who was part of a resistance network of gay men, saved many lives through the forging of identity papers; an activity he is in the midst of in Mercury alongside his compatriots. Outside light appears to be pouring in onto the men and their clandestine operations. Has the door to the bunker been opened? Have they been caught by the all-seeing eye of the surveillance state? Or does the light carry with it more joyous connotations? Are they perhaps free to finally leave the underground?

One can only hope that the beams of light that illuminate the goings-on in Mercury can be traced back to Sun, the third and final painting in Sobczak’s triad. Magic and mysticism are brought in to heal, mend, and fight back, effectively making this painting the exhibition’s white mage. It is perhaps the most visually celebratory piece in the show, not in the least because of the central staging of Luigi Mangione, the billionaire CEO slayer (and bisexual king?) whose sensuous mug shots galvanized a nation against the rich. Here, Mangione takes on the form of a superhero, red cape and all, flying dapperly towards the viewer; a gesture suggesting we might be saved from our oppressor at last? Elsewhere, figures are shown in various stages of healing and recovery. The exposed back of curator and activist Tomek Pawłowski-Jarmołajew – recognizable here by his tramp stamp (an occult symbol if I ever saw one!) – bears the injuries sustained from a homophobic attack; a fate shared by many queer people in and outside of Poland, including Sobczak himself. Tending to these wounds are folk healers, whose knowledge of magic and herbology is not used only as a salve, but also as a weapon to poison and strike back against oppressors, whether they be landowners, billionaires, nobles, or police. The occult and the revolutionary are further blended by the presence of a woman who seems to have entered Sun straight from a communist propaganda poster. She assumes the pose of the tarot deck’s Magus, a card that fittingly represents the power of the will to mold potentiality into direct action.

Real world violence is countered through spells, invocations, and an embrace of the fantastical. It might be tempting to say that in Sun, the tensions built up in Moon and Mercury find a triumphant release through the instrumentalization of magical realism. However, while the colors, title, and iconography indeed carry jubilant undertones, victories are understood to be short-lived; Sun does not deal in escapism. Luigi Mangione is portrayed as a superhero, sure, but he is a shackled one, unable to break free from a corrupted healthcare system or the judiciary closing in on him after what many consider to be an act of heroism. The aforementioned billionaire he slayed, after all, was Brian Thompson, the CEO of UnitedHealthcare whose policies led to the chronic disease and ultimate death of millions of Americans. An old world map containing a centralized personification of the European continent lies burning and trampled under the feet of a nearby figure. It marks a departure from Eurocentrism, perhaps, but no guarantees are made that a new map will be any better –a recent renaming of a certain gulf comes to mind here. Concurrently, the more villainous figures in Sun might prove difficult to vanquish. Amazon’s former CEO Jeff Bezos – portrayed here in full Nosferatu drag against a backdrop of cascading pharmaceuticals – another nod to malpractice in Big Pharma and the healthcare system – seems to be immune to the sunlight. A movie monster typically associated with the plague (the 1922 film was released four years after the Spanish Flu wiped out more than 200.000 Germans[4]), Nosferatu lends himself well to be embodied by Bezos, whose fortune saw massive gains during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.[5]

Having now closed off my ∞ loop through the exhibition, I revisit the aforementioned figure of the Magus, which in the classic tarot game, ties the spiritual to the physical and the eternal to the transitory. Just like Moon, Sun, Mercury in its entirety, the card offers a holistic approach to historic recurrence: as above, so below, in perpetuity. Through his paintings, Mikołaj Sobczak rhymes past events with details from current affairs, bringing to the fore the endless loops through which historical narratives can reconfigure themselves. Each cycle is made idiosyncratic to the era in which it takes place only through its footnotes, ranging from political figures and celebrities to pop-cultural references, technological advancements, and memes, yet continuously echoes the overarching narratives of its predecessor. It is no coincidence then that the Magus card often displays the infinity symbol. Moon, Sun, Mercury indeed encourages infinite ways of engaging with its subject matter; the paintings take on the role of tealeaves, palm lines, or a tarot deck, and allow discerning spectators to unearth a deeper meaning in a detail, or to make grand celestial swoops between the works to discover new ways of thinking about past, present, and future. By preserving the work and lives of queer activists, writers, artists, and scholars onto his paintings, Sobczak’s hand cleverly guides the divining rod: he directs one to envision and foresee a future that is perpetually unyielding and defiant in its queerness. And in our increasingly populist times, where we appear to be in the process of repeating history’s gravest mistakes, perhaps access to that kind of foresight is magic at its most potent.

[1] Engberg-Pedersen, Anders. “Astrological War Media.” Martial Aesthetics: How War Became an Art Form, Stanford University

Press, 2023, pp. 18.

[2] Let the record state that I really liked this person, and that I do not wish to trivialize or ridicule their beliefs in any way.

[3] Ahmed, Sara. “Sexual Orientation.” Queer Phenomenology, Duke University Press, 2006, pp. 107.

[4] Be Kind Rewind. (2024, December 31). Comparing Every Version of Nosferatu. [Video]. YouTube. https://tinyurl.com/yeyke8p8

[5] Sainato, M. (2021, January 12). Billionaires add $1tn to net worth during pandemic as their workers struggle. The Guardian. https://shorturl.at/s5n2R

Artist: Mikołaj Sobczak

Curated by: Mirela Baciak

Exhibition Title: Moon, Sun, Mercury

Venue: Salzburger Kunstverein

Place (Country/Location): Salzburg, AT

Dates: 17.05.2025 – 13.07.2025

Photos: kunst-dokumentation