Katie Zazenski

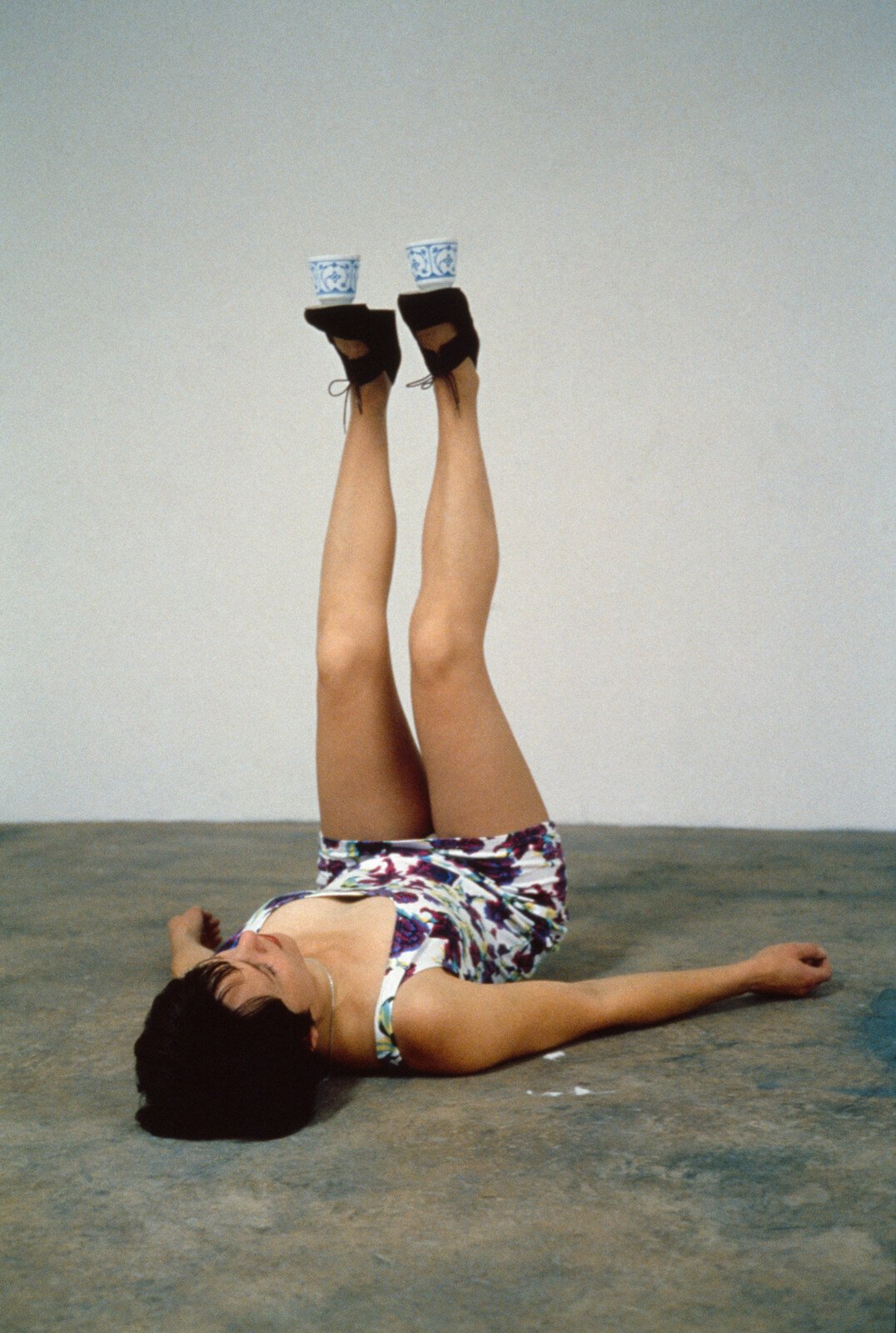

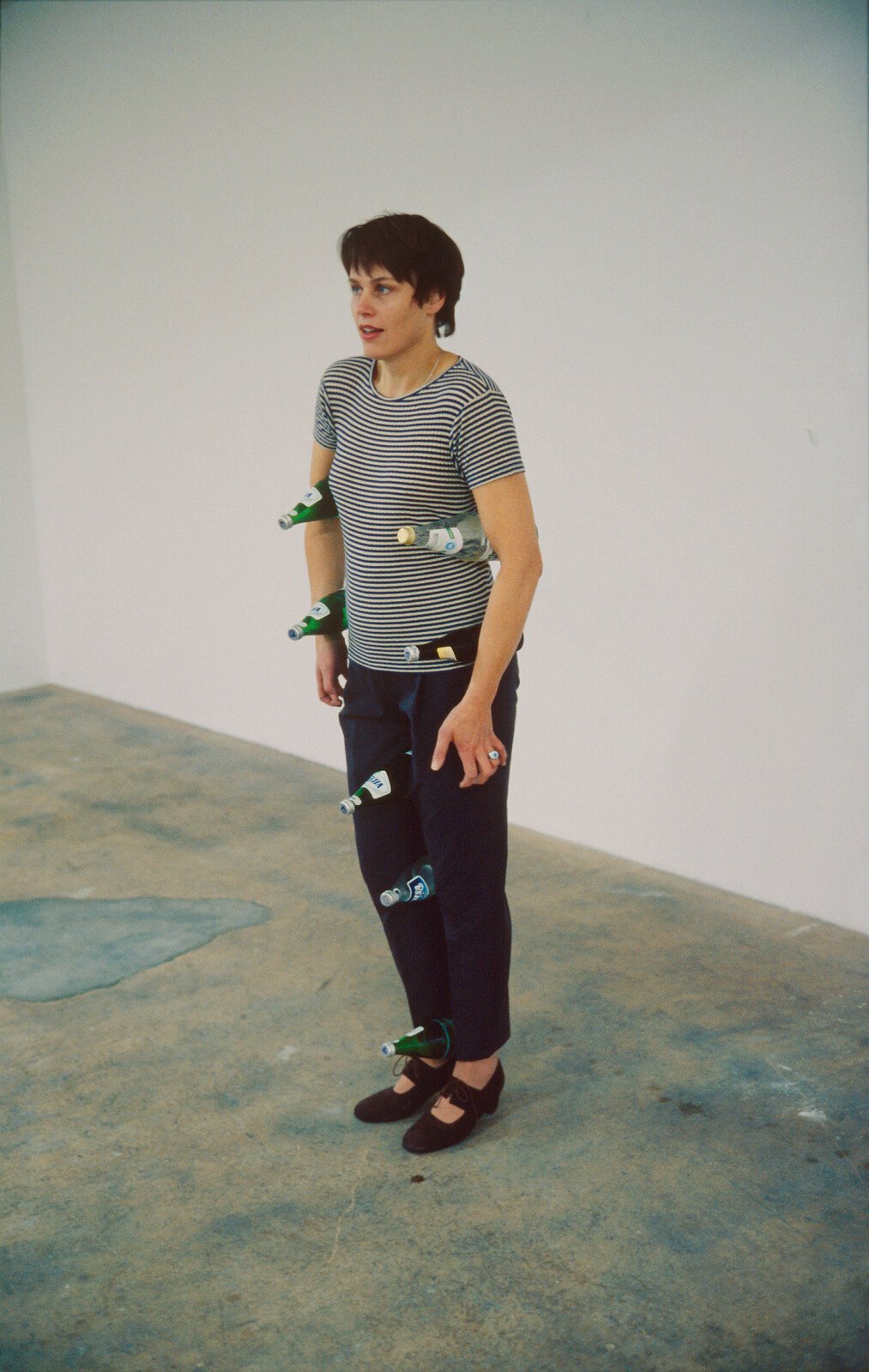

This conversation took place on the occasion of the opening of How It Is, the first solo show of Erwin Wurm in Latvia at the Zuzeum Art Centre. The exhibition collects his works from different periods, presenting a unique perspective on the artist’s singular mix of figuration, philosophy, and the absurd.

Katie Zazenski: How It Is, at the Zuzeum Art Center, is your first solo show in Latvia. Can you talk about the selection of works and how you negotiated what works would be on view?

Erwin Wurm: Working with a museum always means collaborating with the curators and directors—they know the space best. I hadn’t seen the Zuzeum in person beforehand, so we worked from floor plans, photos, and videos. We exchanged ideas and made the selection together. It’s not a retrospective, but rather a group of works from various periods that connect well with each other.

KZ: How important is the local context for you? Was it any sort of significant factor in selecting the work or was it more of a consequence?

EW: It depends on the country and the political or social context. In some places, certain works aren’t welcomed. For example, in Rome I wasn’t allowed to – they didn’t want me to – show the sausages and the cucumbers because they thought it was an insult to men. In England, they asked me to not exhibit the Fat House and Fat Car, thinking they mocked obesity, which was never my intention. The same happened in Russia, the US, and China. These differences are very interesting to me, since, within my work, I’m dealing with social issues. In Riga, however, there were no such issues – everything was possible.

KZ: Just to clarify, were these instances of censorship mostly surrounding Fat Car, or did you experience this with different series in these different places?

EW: No, it was different. As I said, in Italy, it was about the sculptures with cucumbers and sausages. In the States it was with a photographic series, Instructions on How to Be Politically Incorrect. But this was around 2000, and it was reflecting the politics of George W. Bush when he started all this madness.

KZ: That’s super interesting, and makes me think about the recent retrospective of Philip Guston. There was huge controversy surrounding his works, and it really highlighted how important context is for the work, and so I wonder how you navigate that? Is it a simple decision, that the curators prefer not to have this or that, or do you push back in these cases? How do you engage with that?

EW: I was fighting for the pieces that were cut out but I did not succeed! Both in England or in Italy at that time. But in England, afterwards, the director called me and said I’m very sorry about this decision, you were right, we should have put them in. But they had some fears and they decided to not show them.

KZ: I was just listening to an interview with American writer and comedian Seth MacFarlane, who is the writer and producer of this very long standing animated show called Family Guy. He was reflecting on his career as somebody who deals with humor and the intersection of politics and society. And he was reflecting about how some of his work hasn’t necessarily aged in the way that he expected, or that he has a much different perspective now about some of the work he created 20 or 30 years ago. I was thinking about your work and the role of humor and absurdity and how this shifts over time, and shapes the different contexts that your works are perceived within. Is this something you can relate to?

EW: Every art piece has the language of its time – whether it’s now, or in the 90s, or 50s, or 1300 or 5000 BC – it is always related to a certain time and to the language of that time. And of course, time changes quickly, things fall out of concept or they start to be looked at with a different perspective. And then things become strange or very often, even untrue! I’m saying this because I recently did a retrospective in the Albertina Museum in Vienna where I exhibited School, a narrow reproduction of a typical Austrian school from the beginning of the 20th century. People could go in and see, hanging on the wall, a collection of teaching maps and posters from that time. Over time, these materials all fell out of…correctness… they became politically incorrect and their meaning is now twisted. The result is that the knowledge of that time becomes poisoned. This shows clearly that our thinking can eventually, within a different time frame, become poison. And that’s surprising because I think also nowadays we also think we’re correct and so wonderful, but I think maybe in 50 or 60 or 70 years, the same thing will happen to our knowledge.

KZ: Do you have a proposition for at least your own works, for how to kind of ease that transition? Or how to at least help the works get carried through time?

EW: If I would only know! Some art pieces, or also movies or literature…it gets bad. There are many films from the 60s and 70s that I cannot watch anymore because they have a different size, they have a different language, they have a different understanding, they have a different speed, and they just fell out of alignment with everything. It’s like this with art and of course with literature and with all the things. But I think you cannot help it. It’s a part of our being and of our world, it’s a fact. Maybe the same thing is happening to me?

For example when I started the One Minute Sculptures in the 1990s, we used Polaroids to document the performances. Museums would prepare cameras, and visitors could take the pictures home. I’d even sign them. That practice quickly became outdated. Today we have smart phones and we are used to constantly making pictures: also the One Minute Sculptures started to be perceived in a very different way. They exploded online and now have a new life.

KZ: I’m so glad you brought that up. I was actually thinking a lot about that in your works, how you use many traditional approaches to sculpture, whether it be casting or even the notion of the readymade, and so I was curious about the role of technology, of social media, and the internet in your work, if it has had an impact. But it’s quite clear in this example!

EW: I mean, we are all touched by this in a strong sense.

KZ: But it doesn’t seem to enter into the work – maybe it’s more of a consequence [of the work]?

EW: Not directly, but we do use current technologies—AI, 3D scanning, etc. Though I must say, I’m still skeptical about AI’s creative potential. We once asked AI to generate “Erwin Wurm” sculptures. Most were terrible, but a very few examples were surprisingly interesting. We even built two of them, but after a couple of weeks, I realized they felt empty. They didn’t hold up.

KZ: Wow. That’s both surprising and fascinating.

EW: And scary, also!

KZ: I’m curious about the criteria – what made some of them bad and some of them good, if you can articulate it?

EW: I cannot verbalize this criteria, you get a feeling. I look at the pieces and I get the feeling they’re wrong. I cannot even describe what it was – it was an awkwardness, a strangeness. My pieces are always a bit stiff or always a bit, not so convenient, and AI made them not stiff, very convenient, very nice…and this I didn’t like.

KZ: There’s also an interesting point here about the notion of authorship. I wonder if that has any sort of tangential relationship to your practice?

EW: I don’t see AI as one single entity, but as many, many, hundreds of thousands, millions, of people, because AI uses our ideas and, in a way, it’s a concentration of human thought.

But what I wanted to say about authorship relates to the One Minute Sculptures and the Polaroids we used. What happened was: a person would read the instructions to realize the One Minute Sculpture. Then they would follow my instructions and perform the piece. Another person would take a photo of them following those instructions to realize my sculpture. Then they would receive the Polaroid, and I would sign it. So who was the author? They performed the piece, I signed it, and someone else took the photo – it was completely mixed up. I found this process very exciting.

KZ: I wanted to ask a little bit more about the One Minute Sculptures. They’ve actually played a significant role in my pedagogical work; I’ve always found them to be an excellent way to introduce young artists – or not even artists yet, just students – to these beginning moments of sculpture and the basic question of what is sculpture? Could you share a little bit about what inspired those pieces for you? And also, what do you want the audience to come away with, from the experience of the One Minute Sculptures?

EW: I wanted to become a painter. I took the entrance exam for art school, but they didn’t accept me into the painting class, they placed me in sculpture instead. That was a big shock, a big frustration. But after some time, I started to think: maybe this is a challenge, maybe I need to learn what sculpture actually is. This was in the late ’70s, early ’80s. I start to make many, many experiments. What has to happen for that action to become a sculpture? Can it be transformed into sculpture? It’s all about time. So the question became: how do you suspend time, or shift it into a different relation or dimension?

I once had a show where I asked someone to play a pinball machine – eight hours a day, for two weeks. I thought the repetition would slow down time and movement, and that eventually it would turn into a sculpture. I also asked a friend to stand still while wearing a coat. But when I filmed him, I noticed his eyes kept blinking – he couldn’t keep them open and fixed. So I placed a salad bowl over his head so no one would see his eyes, and then I filmed him again. He stood still for a minute, but I looped the footage to run for an hour. The final result is a man standing quietly, his fingers moving slightly. And when you watch the video, your brain starts to play tricks – you think he’s moving, even when he’s not. We’re not built to perceive stillness; we’re built to perceive movement.

Is this still an action, or is it already a sculpture? Where does it lead? I created many works like this as part of my research.

Then I started using my own clothes. I made sculptures that only existed for the duration of the exhibition. I’d take off my sweater, hang it on nails in the wall. That was the artwork. But after the show, I could take the sweater down and wear it again. These pieces had a beginning and an end – which is unusual for art, because we often assume art must last forever.

The action became increasingly central to me, and that I would keep the original. And then all of a sudden, I had this idea about “short living.” I realised that eventually every object in my world, in my life, is a possible beginning of an art piece. Everything was possible. It was an enormous sense of freedom.

But let me add this: these pieces aren’t just absurd – they deal with a wide range of psychological topics, and yes, sometimes with stupidity. They can verge on slapstick, what in German we call klamauk. But I had serious concerns, both about sculpture and about social issues. I never wanted the works to become jokes. That’s why I asked participants to approach the instructions seriously, almost like meditation – calm, focused, not laughing. I only showed them in museums, to keep out distractions. Over the years, I was invited many times to do One Minute Sculptures at parties – people would say, “it would be so fun!” But I always declined. That refusal was essential to protecting the integrity of the work. And now, it’s wonderful: major museums are interested in showing them, and the pieces are exhibited all over the world.

KZ: To practice yoga or meditation, you must engage in the present, you must be present. I was thinking about that so much in relation to your series of work, Substitutes – these kind of bodiless clothing sculptures, and the relation between absence and presence in these works. Can talk a little bit about this – the presence that comes from the absence of the human body?

EW: In the 1980s, I made sculptures using materials that other people had thrown away – old wooden boards, scrap materials, metal, and so on. At the time, I had read that if you want to succeed, you have to overcome your fathers. So I told myself: I have to try something different. Otherwise, I’d just be one of many, standing in line behind a thousand others. So I began creating works that felt out of time – both in concept and appearance. I tried to make classical sculptures out of rotten or discarded materials. It worked to an extent, I had some success. There were collectors, galleries, all of that. But then, gradually, I realized: this isn’t the direction I want to pursue. My art was reacting to specific external circumstances and I wanted to get away from that.

I started looking for the zero point of sculpture. How could I define that? One approach was to use dust. At the Venice Biennale in 1990, I showed the shape of an object only as a trace made by dust – just rectangular shapes, no identifiable form. It was about the absence of the object – a total zero point. But the audience could still imagine what had been there. Interestingly, even the dust was fake, and the object was fake – I had staged everything. I placed the dust myself to suggest something had once stood there. Yet in the minds of viewers, the object existed. That power of imagination became central.

From there, I began working with clothing – dresses, coats, trousers – because they act as a second skin. Think of Roman or Greek sculptures – those massive bronze figures of gods, warriors, horses—they’re hollow, defined by only a thin skin of metal. That emptiness inspired the idea of clothing as second skin. And again, something was missing: the body.

So first the object was missing, then the body was missing. And that line of inquiry continued as the Substitutes series.

KZ: Going back to this notion of the imagination, the scale shift in this series [Substitutes] is also really interesting; some of them are larger than life. How do you work with scale in these pieces?

EW: Scale has always been important to me. Playing with reality also means playing with scale. And surprisingly, it’s quite simple – but it works incredibly well! It still surprises me every time.

I’ve made oversized food items – huge loaves of bread, giant pistons, big cars. Because of that, many people feel my work is easy to access, which is only partly true. There are many layers of thought behind it.

KZ: Thinking about what you said earlier, about “escaping our fathers” I’m reminded of Klaus Oldenburg and his big sculptures or Duchamp with his photo of the dust, and I’m wondering, is it ever possible to escape them?

EW: No! I mean, look around now. Everybody uses everybody. There is a Japanese designer who said something like, “steal, steal, steal, and then you will invent something new out of it.” You know, I didn’t steal the idea of Duchamp. But yes, I’m inspired by many artists and by literature and philosophy and film and everything else!

KZ: Thank you so much for your time.

EW: Thank you.

Artist: Erwin Wurm

Exhibition Title: How It Is

Venues: Zuzeum Art Center

Place (Country/Location): Riga, Latvia

Dates: 13.06 – 14.09.2025

Photos: Various