A conversation between artist Sabīne Šnē and artist and interdisciplinary cultural researcher Annemarie Reichenbach about art-making in a climate shaped by extraction, entanglement, and transformation.

Sabīne Šnē: We met last summer in a small town in the western part of Latvia, each of us working on our own projects. I was at a residency, researching traces of the Soviet period in natural landscapes and creating artwork about how that totalitarian regime altered, changed, and destroyed environments. You were part of the team organising an eco-art therapy community residency.

When we started talking about sustainable practices and making art in today’s world, you came up with the idea to create a decision tree-style diagram that would put structure into otherwise very broad topics. I thought it was a brilliant approach. Whenever people, including us, talk about ecologies and environments, there are so many factors to consider. So many ethical questions to ask. And so many large, planetary-scale processes closely linked to our silly little lives. I wrote down some of the questions I consider important, or ones I feel I should pay more attention to. I also mapped out possible paths forward. Throughout this, I kept in mind how interconnected everything is. But I never questioned why you suggested a decision tree specifically.

Annemarie Reichenbach: When you approached me, I was thinking back to our summer afternoon: how we did not need a long time to get into deep conversations. Since we were born in the same year, I wondered: what if we would have shared after-school bus rides? Would we have been able to foster similar conversations then, influenced by what we had learned before and especially by what we had not learned? Early on we had realised how being curious together is a catalyst for connection, but also how knowledge can be leaky: uncontained, spreading, flowing.

From those childhood bus rides I remember completing those decision trees in magazines, or coming up with them myself, as a way to communicate more complex thoughts and be playful with them. Now, I also see it as countering rigid structures: although we are moving through our decisions in a linear way, we are also not. We do not have to accept it as an endpoint, but can retrace our steps. A decision has a consequence, but we have in front of us what unfolds when we take our decision back. Decision trees are very much associated with and commonly used in machine learning now, so I felt excited to adapt this format to a rather different pursuit: Can we disrupt the format, and are there blindspots? Will it assist us in our ongoing process of knowing and forgetting, shifting perspective on what and how we create? Are we arriving at a decision or rather more questions? How do we recognize the relation between questions and each other’s work, when mapped out? How can we experiment further with it?

Once the seed of the idea of a decision tree was planted between us, our writing and wondering took on a flow of its own. I have always been interested in how theory and art could be nourishing for each other. For this particular conversation, the decision tree became a co-facilitator between us.

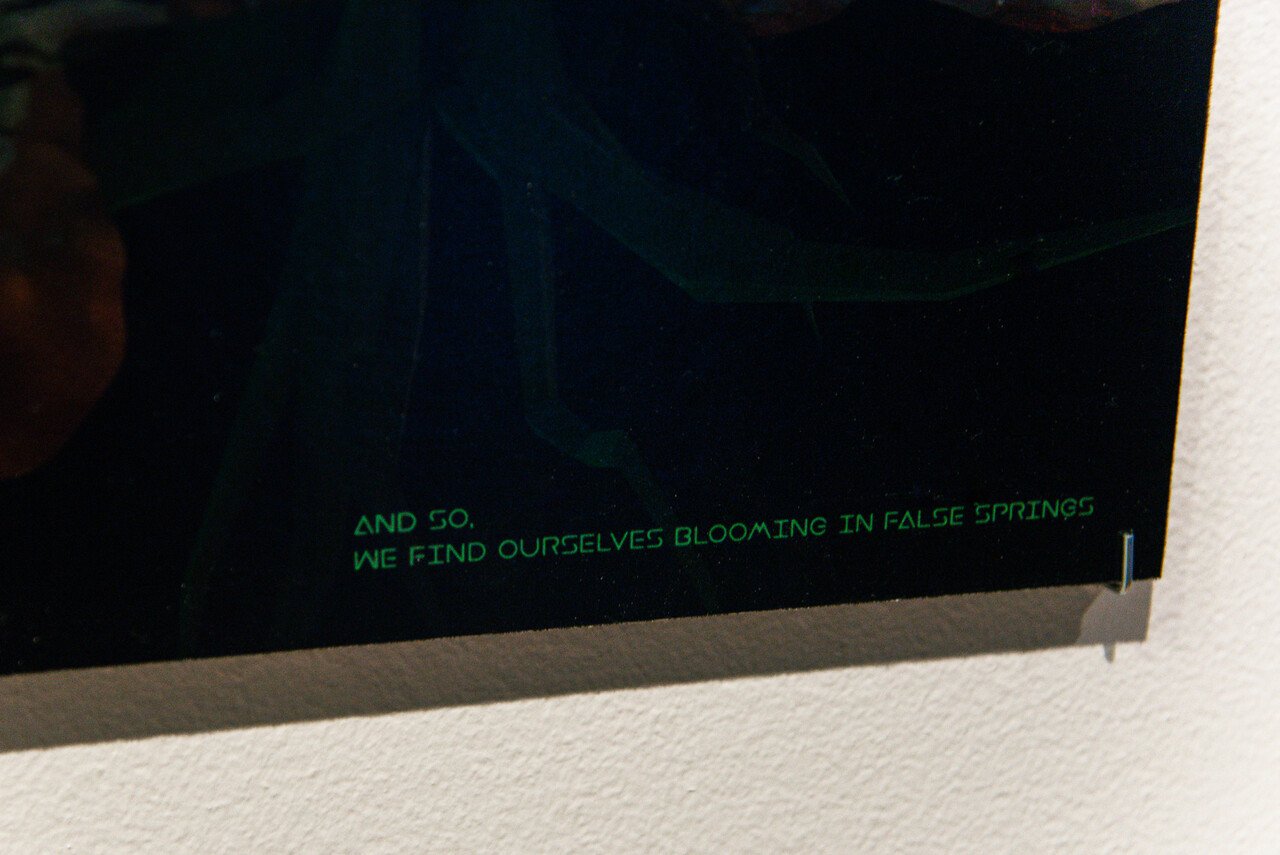

SŠ: I often create mind maps, more like spider diagrams, while researching new topics for artworks and generating ideas for how they might eventually look. This thought exchange takes place while my solo exhibition Tidal Tear Sediment is on view at RIXC Gallery in Riga, Latvia. While working on the artworks for it, my studio walls became a site for a mind map, where I tried to think of the best ways to show that the water in my body is linked to the waters of the ocean. That my body is impacted by melting glaciers, changing streams, and lakes that are drying out.

Every new artwork comes together with careful consideration for the most appropriate materials to use. I try to find the most environmentally friendly options, while remaining aware that everything I do harms the planet in one way or another. There is no way to escape that, but there are different levels of awareness, care, and also ignorance. Whenever I start to think about this, I often end up reflecting on the absurd separation between nature and culture. This is something many posthumanist theories address: refusing the idea of the environment as something “out there,” separate from the human subject. We are part of the Earth. We are also part of political and economic systems filled with inequality, anthropocentric hierarchies, white supremacy, wars, ecocides, and well, everything else. A wicked world, where it is sometimes hard to find paths for coexistence. But we all do have the same roots. What is your path through the decision tree branches?

AR: I stumble over the bigger questions only so I can get lost in the smaller ones. The ones that are barely whispered are what I am after. “Is it possible to create an ecological art project?” Is ecology a project, or a state of being? Have the artists created in a communal way, embedded in some sort of system and interdependence, or are they creating art only to become independent from all sorts of entanglements? Entanglement, another buzzword, when metaphors from the wild world are borrowed from God-knows-where. In Staying with the Trouble, Haraway mildly and matter-of-factly surrounds herself with truths applicable to all, applicable to this text, applicable to you: “Nobody lives everywhere; everybody lives somewhere. Nothing is connected to everything; everything is connected to something” (31). You caption your exhibition Tidal Tear Sediment, Sabīne, with the words: “all of us and no ‘others’ – just entanglements“ – Where did you live at the time of imagining this exhibition? Were you called to create an ecological art project?

SŠ: Physically, I was in London, although most of the works were made while I was in residency in Paris. But mentally, I was longing to be by the sea. There is something calming about being able to see the horizon line. The beaches in Latvia, where I am from, feel very special to me.

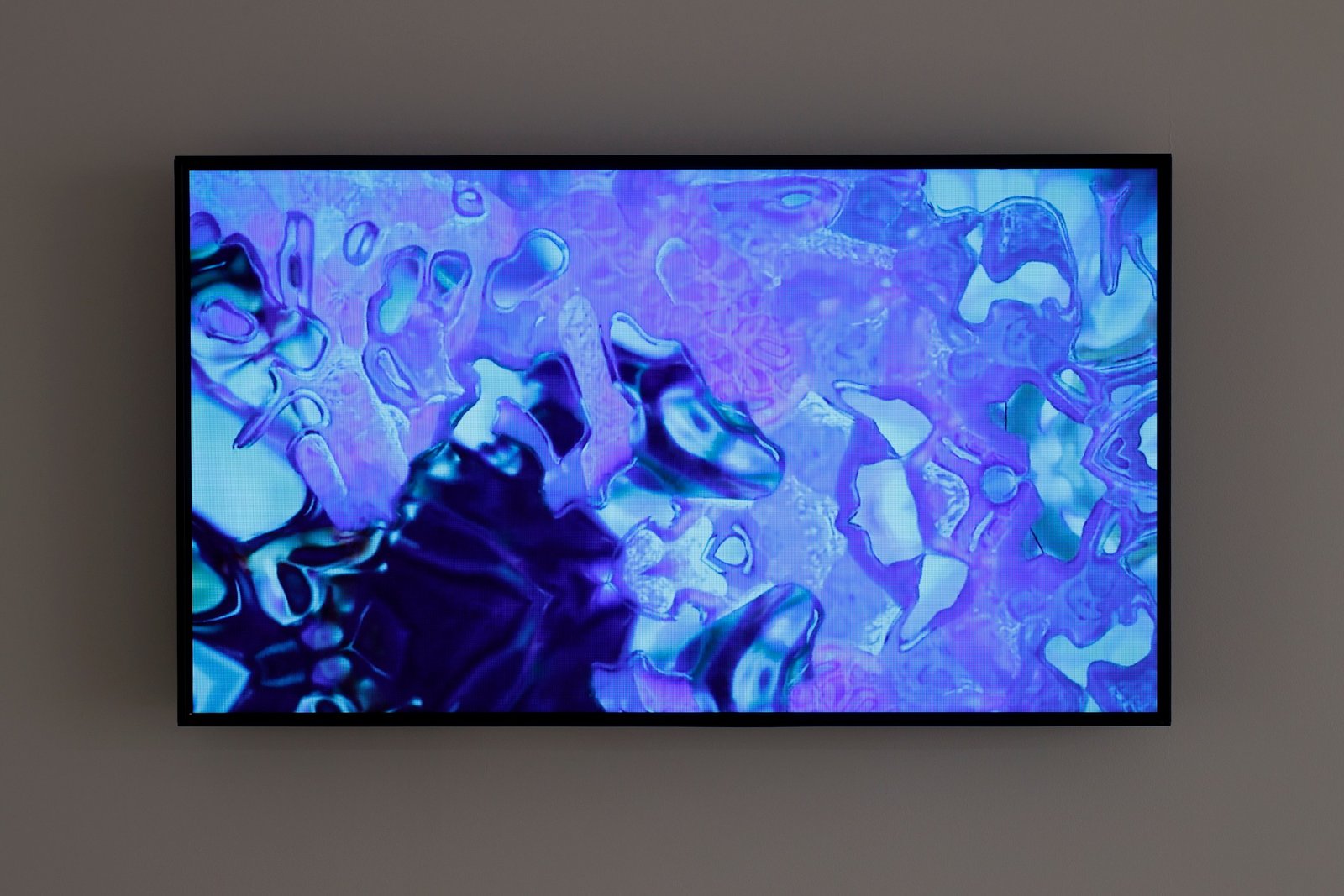

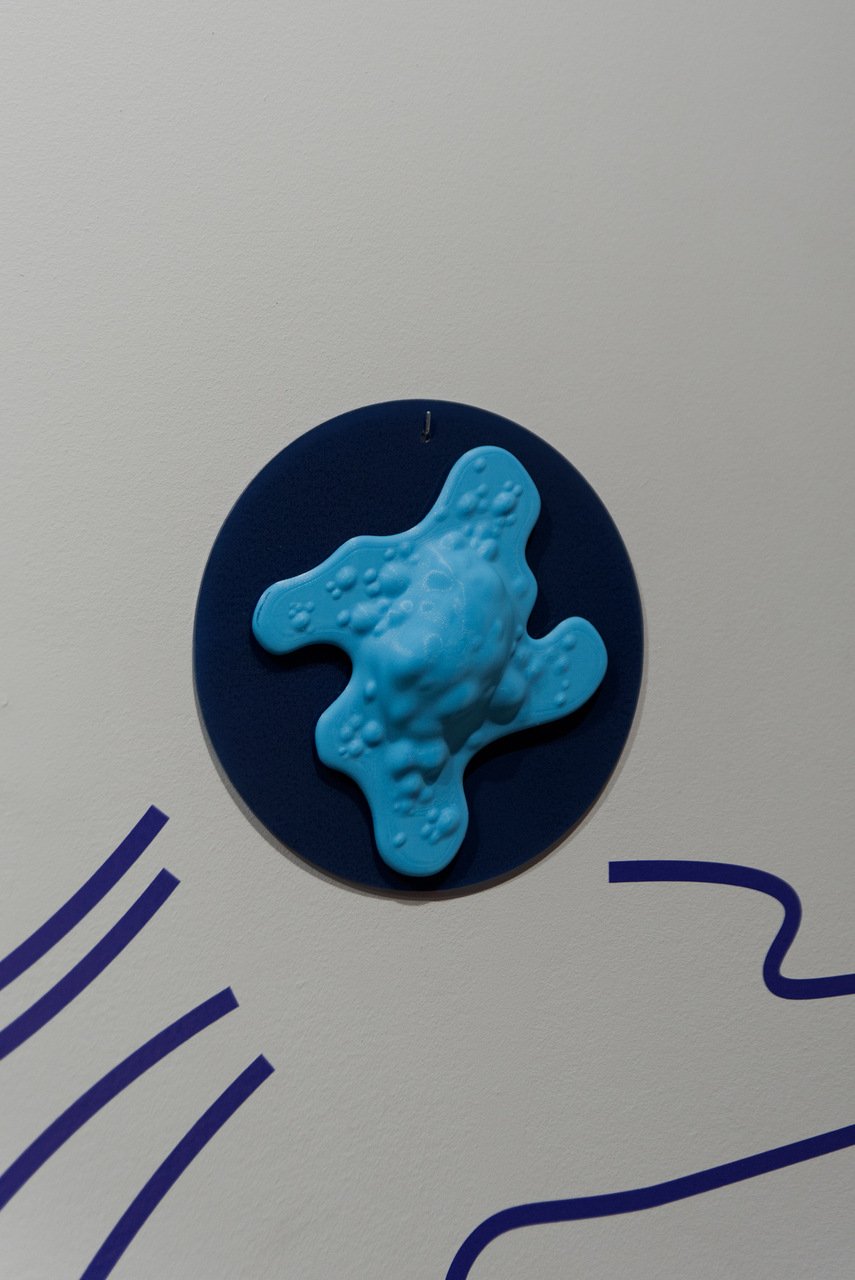

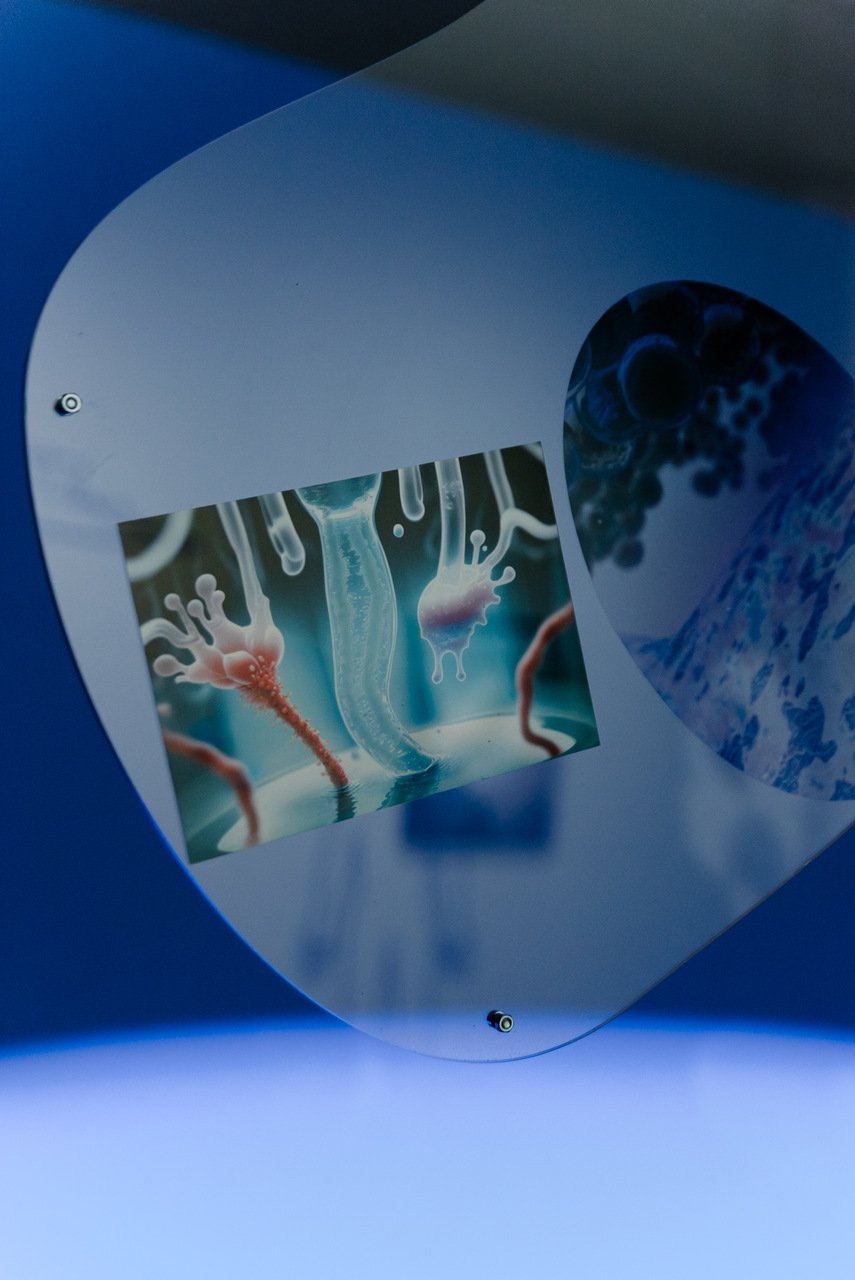

In very simple terms, Tidal Tear Sediment is about how the living world is a water world. Every living being needs water to survive and exist. The exhibition draws heavily on Astrida Neimanis’ ideas about hydrofeminism, which highlights that water runs through all our bodies and, through it, we are connected to each other and to the planet. The video, sound pieces, prints of digital drawings, and sculptural objects follow the path of a water molecule, tracing its journey from falling out of a cloud to reaching the Baltic Sea, passing through the human body, and then returning to the atmosphere. Throughout the exhibition, some people asked why I chose a water molecule as the main protagonist. Firstly, to emphasise that humans are not the central element in the world. But also because I find it fascinating that such a tiny entity, when joining with other equally microscopic beings, creates something as massive as the planetary water cycle. It is about playing with scale, zooming in and zooming out, looking at myself and looking at everything that makes life possible.

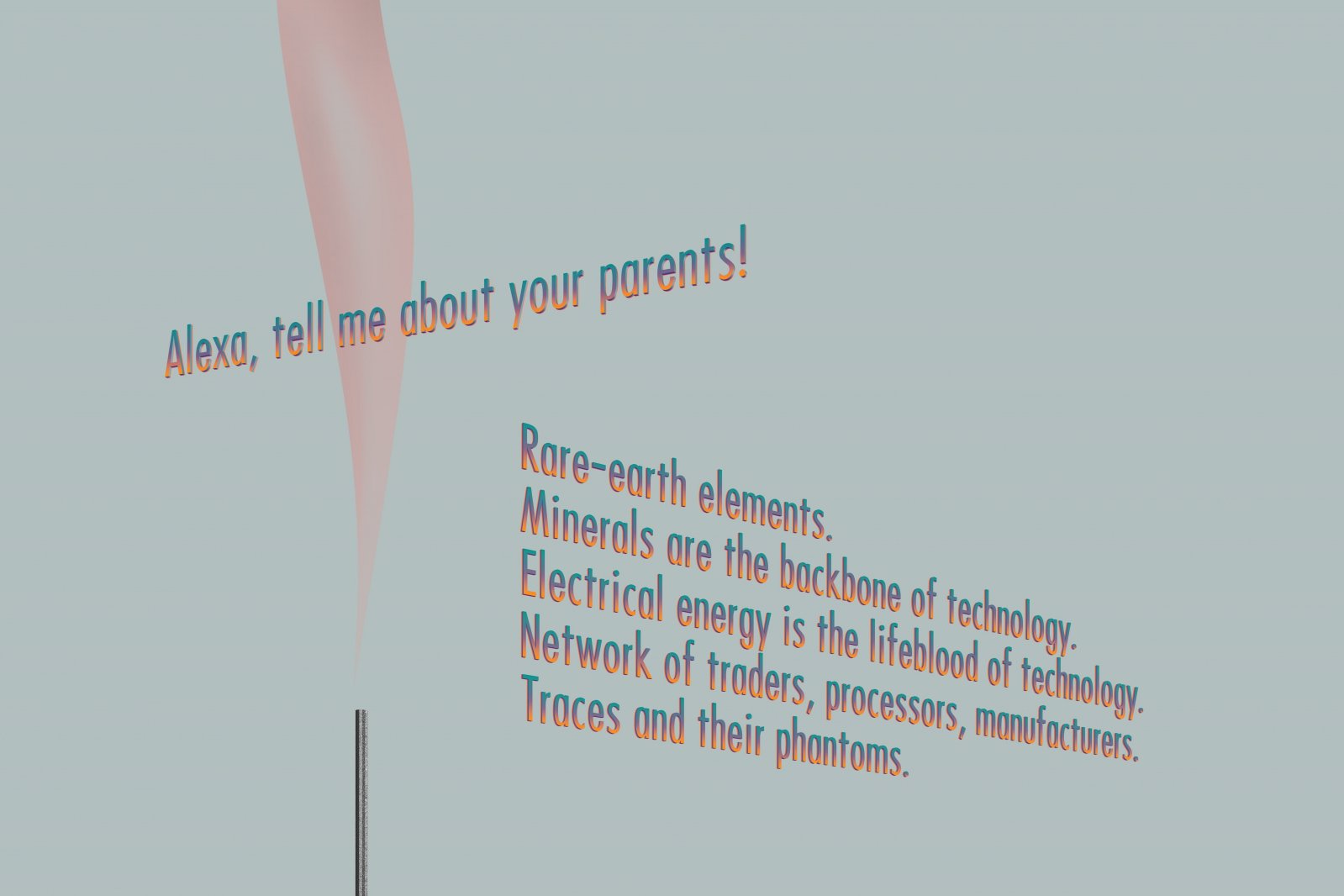

As for the idea of an ecological art project, I believe that truly ecological art is not possible. However, I think it should be the goal, even if it remains unrealistic. Creating works about environmental issues and toxicity is important, but sometimes the chosen medium risks undermining the message. I use worlding methods in my practice, but digital world-making, like any other form of creation, leaves a footprint. It is part of a chain involving Earth’s resources, extractivism, human labour, and socio-economic privilege. That being said, I will continue to make art, and for the foreseeable future, I will continue to use digital tools to do so. However, I feel that questioning environmental ethics opens more paths for reconsidering who is within and around us, what makes us, and why we are here. We live deeply entangled lives, and that entanglement creates possibilities for care, both for each other and for ourselves. It also demands that we oppose structures that continue to profit from questionable power relations. Ecology is not about adapting, changing, or dominating nature to our will. It is about recognising that we are already within the will of the natural world.

AR: And yet again we strive to give words to what we cannot explain, whereas the art process fundamentally requires us to let go of explanations. No – I don’t agree that it is possible to create an ecological art project because despite trying, I am rarely able to achieve this. Especially when I embed myself into ecologies I claim to belong to, those that are artistic. In spring, pollen are disagreeing with my conditions although I am drawn to the colours of the blossoming beings; and in winter, when everyone disagrees with the cold, I find relief, even though I did not grow up in particularly cold climates. “It’s inherently contradictory,” now, that’s what I can sympathize with, although harsh to read at first. Beneath it, the branches of the tree unfold into further questions, leading me to: “If an artwork is complicit, can care still be a method inspired by posthumanist ideas?”

“Yes” and “no” are such harsh choices, but I revel in their clarity, reminiscing about how freeing it can feel when our bodies communicate a hard no or a full yes with us. Whenever I care, I go for a “yes” but this time I cannot, there is only a “no.” If I want to get to the center of the decision tree, to the heart of the matters, I have to choose “no.” I arrive at the question: “Is imperfect action better than ignorance?” Now, from my “yes” uttered out loud and wholeheartedly, I venture on a journey straight to the next question: “What triggers ideas of multispecies futures and more-than-human rights?” I realise that I have glossed over the “care” question, although it’s not that I do not care about it but rather I followed a gut instinct. This next question has other possible answers than yes or no, it refuses to be abstract and honors how I regard your art: as a dedication to being in-the-mix. Although I would want to go for all of them, I choose “recognising intimacy with the more-than-human within us.” Immediately, memories are flooding into my consciousness and now into my fingers, who are going to type them for others to read. The smell of the seaside whilst being in rehabilitation; how bitter the taste of the medicine was they had given me. The sharp edges of trash brought in by a harsh sea, but I was taught that if I waited a few years, the sand would make those edges less sharp and I could collect it for mosaics. Do you have memories like that?

SŠ: I think water is a good example for thinking about this. It brings all kinds and types of bodies into intimate contact. For instance, the water within our own bodies, and all the bacteria living there, forming their own microbiome. Biologist Lynn Margulis has suggested that humans are a “holobiont,” an assemblage of a host organism and its microbial, bacterial, and viral partners. This means there is no permanent state of self, we are always shifting and growing. And speaking of memories, yes, I do have quite a few. As a child, I spent a lot of time at my family’s countryside house, playing with blue mussels in the local lake, trying to figure out how earthworms breathe under the surface, and making tree leaf snacks for my grandmother’s chickens.

I also remember reading a lot of folk tales. The relationships between body and landscape in these stories, and the magic of this place, has stayed with me. Trees that could talk, swamps that formed otherworldly zones, lakes flying through the sky looking for the perfect place to land, different variations of natural deities, and human protagonists making their way with the help of animals, stones, or mythical creatures. Stories filled with paganism and wilderness. I love Latvian folktales because they acknowledge other living beings as equally important. It is not like many tales from so-called Western cultures, where a knight journeys through a dark wilderness, kills the dragon, and saves the maiden. That represents a completely different way of shaping relationships with the Earth. I prefer the stories that I grew up with, the kind that embodies environmental wisdom.

AR: Ever since I am learning about what breath can do, I notice when I hold it. I hold it most often when I have answers deep inside of me but don’t dare to speak them out loud. Where does this answer lead me?

“How can tuning in to microscopic biomes or planetary processes help with uncertainty?” I want to start by acknowledging how uncertain I was for a long time about the concept of temporality itself. Also, do you have a go-to methodology for tuning in to microscopic biomes or planetary processes, and how does your art represent that? Do you design it to offer help? I realise I have come down in the decision tree, closer to the roots, but also further away from the multitude of possibilities at the top. I can tell that when we discuss temporality and uncertainty as markers of our times, we hone in on what is tangible. We describe what a year is by following the planets and how they are in movement with each other, we describe seasons and their shifts by how other-than-human beings exist in time. Let’s find grounding in the answers, where one question leads to the next. The decision tree has a wonderful way of providing a path for the hesitation that comes after the question. I will choose “resilience and survival often come through collaboration, feedback loops, and mutual dependency,” mainly because I am attuned to the concept of resilience, and because of it being what I question the most in recent times.

Is resilience somewhat dangerous because it invites us to bounce back? And, is there a state we want to go back to? Which wisdom can be found in remaining in a state of despair, an invitation to question on a deeper level what carries an energy of defeat? To recognize ecological grief and not bounce back to assuming ecologies as a given site for extraction for our delight? Equally, are feedback loops reserved for nervous systems that have been built like that, and is our thinking interrupting the feedback loops of our bodies affected by the climate crisis? Where do feedback loops mainly help us adapt to changing circumstances, and can that be seen critically also? I want to go back to my earlier question to you, dear friend, how can we tune in to microscopic biomes on those matters? Please tell me how learning from nature is ethical. It is not the first time I trust friendships to provide me with knowledges I did not encounter through the school system.

SŠ: I think instead of looking backwards or trying to figure out what kind of future lies ahead, we should look around. We should think about relationships and kinships. I think the reason why I enjoy ecological storytelling is because the questions are more important than the answers. Conversations are more important than monologues, and relationships are more important than individuals. It roots humans back into where they belong, back into our shared ecosystem. You know what else I find extremely important? Listening. An ecosystem is a space, and every sound inhabits a different part of that space. At the moment, humans are disturbing other beings with a lot of noise. We should understand ourselves as part of a web of relationships. After all, ecology comes from the Greek word oikos, meaning household. We all share one home.

We are porous beings, part of a constant flow of carbon and water. And whenever I create an artwork, I keep in mind how special it is that, due to so many biological, chemical, and geological events, that we can be here in the first place. And how smart and self-sufficient natural systems are. That’s why I love working with topics like water, soil, trees, fungi and mycelium, lichens, different minerals. They have been here before us and they thrive in symbiosis. Yes, we should be scared for the future, because it does look doomed, but in the natural world, every end is a new beginning. There is a chance that our bodies will find ways to consume microplastics and polluted air, and who knows what else. The wheel of evolution is always in motion.

But of course, it is much harder to nurture kinships and healthy relationships when someone is not letting you do that, when someone is not letting you live. I have thought a lot about ecocides as products of the wars that are taking place. When landscapes are filled with holes from missiles and the Earth is burning. When imperial violence takes place, it often comes together with the weaponisation of nature against its own people. It shows that those who think they can dominate nature and other beings have no sense of how interconnected living systems are. It also shows how deeply climate collapse is intertwined with all other aspects of our lives.

AR: I have almost arrived, and there is no time to wonder if I am any wiser by this point. “Transformation can end something or someone, but in the ashes, a new spark might flicker.” I do not know if you are aware of this, but the keyword “spark” accompanied me this summer in rural Latvia, where we both met. I must admit, I am not comfortable with the word “new,” but I have arrived at the bottom of the decision tree and am affected by my choices until then. I am known as a sentimentalist, I am fascinated by how the natures that I grew up with return to states of decay. The berries on my great-grandma’s raspberry cane do not have a new taste in the years following their abundant harvest. The comfort of them lies in being known, reliable. Moreover, I am deeply critical about what is done, and which resources are depleted, in the name of progress. How do you feel about having to make something “new” in terms of the art world, something that has not been done before, or something that is shocking during your lifetime that later becomes a canonized? Is there such a thing for ecological art already? Maybe I am naive and I have cared for the ashes for too long. As a rope, I hold on to the question: “Who gets to decide what is going to happen?”

SŠ: Regarding my practice, there’s no clear-cut division between one project and the next. Thematically, it’s always about the relationships between humans and the more-than-human, or between ecology and technology. For instance, for my first solo exhibition three years ago, I created a work that explored whether humans are in a loving relationship with Earth or if we’re simply parasites. It was titled Partner, Parasite and took place at KIM? Contemporary Art Centre in Riga, Latvia. I was inspired by Gaia theory, which suggests that Earth is a self-regulating living organism and that humans are merely guests here. From there, I became fascinated with deep time, which led to research on extractivism. This culminated in a work about rare earth minerals and their role in technologies, titled Grey Gold, Black Lake, White Latex. This, let’s call it investigation, made me consider what’s happening beneath the Earth’s surface, which led me to discover the remarkable capabilities of mycelium, an underground network that transports nutrients and nature-based data between trees. Combining this with research on lichens, blue mussels, and dung beetles, I created a mixed-media installation about a speculative post-apocalyptic world where those four entities are restoring the Earth after human impact. This became the basis for my solo exhibition in London, titled To Be We Need to Know the River.

As you can tell, I could go on and on about the fluid transitions from one work to the next. The natural world continues to amaze, and there’s this constant urge to translate that wonder into my work. And I agree with you about the word ”new.” The phrase “there is nothing new under the sun,” attributed in the Bible to King Solomon, for some reason is deeply rooted in my mind. However, I much prefer to quote what I think of as an upgraded version of this idea, from the science fiction writer Octavia E. Butler: “There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” This version opens up space for imagining new possibilities, new worlds, and new ways of being. One could also replace ”new” with ”different”, which for me offers hope that patterns and actions which no longer work can be replaced with ones that do. It reminds me that we can adapt to change, and that we will do so when the situation demands it.

Occasionally, I think there is something new in the art world. For example, current ideas and works about quantum entanglement, inspired by discoveries in quantum physics and advances in quantum computing, seem new to me. But I would never put pressure on myself to think of something that no one has ever thought of before. That would be cruel. Ideas are constantly floating around, and although our upbringings and life situations differ, we share the same world events and issues that impact us all.

AR: If we could, and who wouldn’t let us, I would like us to go back to the first question, to spiral back. I notice the craving to have us hold all those questions, all those decisions, in our hands, together. To become grabbed by them, and to show others how they bind and inspire our creating hands – how they confuse and embellish our creating minds. Once again, I am reminded of Donna Haraway, who proposes string figuring as a storytelling device, and with it, recognizes the universal game as one of the oldest cultural techniques known to humanity. What if all of the decisions we arrived at were a single loop of string in our hands, that slowly emerged into a pattern? What if our ecological art, however comfortable we want to feel with that description or not, would be woven into those strings – fleeting moments of visual overlap between lines and lines in movement? A string figure, much like a decision tree, becomes a third thing between our minds in communication about what we see, what we feel, and more often, what we see-feel. We invite others to join the game, recognizing it is some serious, indulgent, radical play of words on issues that matter deeply to us.

Is it possible to hold all of those questions, have more emerge, and keep on creating with them? What do you think my friend?

SŠ: It is, and at the same time it is not that hard. It just takes a bit of time to shift perspective and recognise the importance of earthbound connections and multi-species futures.

Riga/Dresden, April 2025