Rebeka Erdélyi

1. Introduction

Nostalgia plays an important role in shaping post-socialist memory, influencing not only the political, but the cultural discourse in the region. Svetlana Boym differentiates between two types of nostalgia in post-socialist societies: restorative nostalgia, which seeks to revive old national symbols and ideals, and reflective nostalgia, which critically examines the failures of neoliberalism and unfulfilled promises of democracy.[1] I believe this tension between using memory as a tool for reviving/glorifying the past, or as a critical lens for examining it, is central to contemporary art and theory in Central and Eastern Europe.[2] Within this framework, Easternfuturism emerges as a method of reimagining history; building on the temporal multiplicity of reflective nostalgia while offering an alternative to both nationalist revivalism and Western-centric narratives of progress. Instead of returning to the past, or attempting to erase it in favour of a singular vision of the future, it constructs speculative futures that challenge dominant linear models of historical time, offering alternative historical and political imaginaries. Rather than seeing history as a straight line from past to present, it is more useful to understand it as multiple, overlapping temporalities that constantly interact and influence each other.

In Kajet Journal’s issue 05, On Easterfuturism (2022), editors Petrică Mogoș and Laura Naum discuss the implications of disappearing futures, arguing that imagining a better future has transformed into a “worn out ideal,” which is increasingly being erased from the collective imagination. They attribute this collapse of future-oriented thinking, in part, to the global dominance of capitalism, which positions itself as the ultimate (and inevitable) system. In response, Mogoș and Naum propose Easternfuturism as a prototype for remapping the future of a region that has, in some senses, disappeared. The editors highlight the need for a pluralistic perception of time and a coexistence of futures rather than a singular narrative dictated by dominant, Western frameworks of historical development.[3] By rejecting the notion of time as a singular, linear trajectory, Easternfuturism challenges nationalist and colonial temporalities, emphasizing alternative ways of engaging with history. This rejection of linear temporality is not just a speculative exercise, but requires a fundamental rethinking of how history itself is structured and narrated. If time is not a singular, hierarchical progression, then neither should art history or cultural memory be confined to vertical, Western-centric models of development.

2. Post-Socialist Nostalgia

Boym argues that nostalgia is not just about longing for a lost place, but also for a different time. Nostalgia, then, is not just about geography, but a sense of temporal dislocation – the feeling of belonging to a moment that no longer exists or that was never fully realized. Although nostalgia often looks backwards, it also shapes how we imagine what is to come. This means that nostalgia is not just about memory but also about power, about who gets to define historical narratives and how they impact the future.[4]

Restorative nostalgia in nationalist movements is shaped by this idea of returning to the origins, mythologizing the nation’s past as pure and uncorrupted, blaming external forces like the West, the EU, or globalization, for its decline.[5] This type of nostalgia not only reconstructs an idealized past but also often functions – consciously or unconsciously – as a counter-response to new political and cultural developments. This can be seen particularly in cases like Hungary, where the national rhetoric often frames past historical events as “proof” that the country had been undermined by foreign powers, which fosters a sense of historical injustice and national victimhood. This is particularly visible in Hungarian political discourse surrounding the European Union and migration policies, as the EU is frequently depicted as an entity that undermines national sovereignty, imposing foreign values that threaten Hungarian identity and traditional structures. For instance, the Treaty of Trianon (1920)[6] is frequently cited as a symbol of historical injustice, used in nationalist discourse to reinforce a sense of external betrayal and victimhood. It is mobilized to justify territorial revisionist sentiments, add to a nationalist rhetoric, and promote a narrative of historical grievance justifying contemporary political decisions.

By contrast, reflective nostalgia does not attempt to restore the past but rather engages with its contradictions and ambiguities. Instead of promoting a singular historical truth, it acknowledges a layered, nonlinear nature, resisting the notion that time follows a singular trajectory of progress.[7] This distinction between restorative and reflective nostalgia is crucial for understanding how historical memory operates in post-socialist societies. It also helps explain how alternative historical imaginaries, such as Easternfuturism, emerge as a form of resistance against both the nationalist misuse of nostalgia and the linear Western framework of history. Rather than fixating on an idealized past or a singular future, reflective nostalgia moves sideways, creating a multiplicity of pasts to reimagine more open-ended futures.[8] It resists the rigid confines of time and space, emphasizing that what is often longed for is not a specific historical moment or homeland, but rather the shared cultural experience of a time and space that no longer exists (if it ever did at all). In this way, Easternfuturism takes responsibility for nostalgia rather than allowing it to be prefabricated by dominant ideologies. By embracing speculative temporality and collective storytelling, it proposes that history and memory should not be static but fluid, participatory, and open to reinterpretation.

3. Horizontal Art History as a Theoretical Base

Piotr Piotrowski’s (1952-2015) concept of horizontal art history provides a useful framework for understanding how Easternfuturism resists imposed narratives of progress, offering a more decentralized and pluralistic approach to historical engagement. His theory directly challenges the dominant Eurocentric art historical models, which structure modern art through a hierarchical geography of center-periphery relations.[9] Piotrowski defied the assumption that there is a sort of “universal” (i.e. Western) history of modern art, which is based on a structured hierarchy of art history that focuses on centre-periphery relations. He also questioned the dominant way in which art history is defined, where artistic movements are described as following a single, linear progression from one style to the next. In reality, different regions experience artistic developments differently, but this complexity is often overlooked in favour of a simplified, Western-centric timeline. I find Piotrowski’s approach particularly useful in reconsidering how art is studied, viewed, and discussed, particularly in regions where the Western framework does not apply.[10] This challenge to hierarchical narratives aligns with Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann’s adaptation of geohistory as an additional framework through which to examine art history, one that emphasizes the importance of considering political borders, cultural boundaries, and historical specificities in understanding artistic production. By incorporating geographical dimensions into art history, Kaufmann’s approach emphasizes the importance of identity, policy, and exchange in shaping artistic expressions while challenging traditional classifications that may ignore the influence of specific locations and their histories on art.[11] By neglecting the critical perspectives of geography and geohistory, a textbook or study may fail to convey how particular locations and histories contribute to an artwork’s nature and significance.

The continued reliance on hierarchical frameworks in art history raises an important question: Can we move beyond a model that ranks artistic production within a singular, linear framework of modernity and instead adopt a more nuanced, decentralized approach that acknowledges regional specificities and multiple artistic trajectories? Both Piotrowski and Kaufmann’s concepts offer ways to decentralize art history and emphasize regional specificities while rejecting externally-imposed center-periphery relations. However, while horizontal art history provides a compelling theoretical framework, its practical application in post-socialist contexts is more challenging.

Edit András reexamines Piotrowski’s focus on regional specificity, highlighting the risks of implementing a strong regional perspective, especially in recent times, as nationalism has become increasingly visible.[12] The concerns she raises are particularly relevant in post-socialist Europe, where there is a tension between embracing regional diversity and a growing push for a return to universal values. On one hand, foregrounding the specificity of post-socialist art histories can provide necessary visibility to marginalized cultures. However, highlighting these differences can sometimes be used by nationalist and populist movements to shape culture in a way that reinforces exclusion and division. Alternatively, returning to a universal art historical framework risks treating the region as a homogeneous bloc, erasing its internal complexities.[13] As András argues, post-socialist art history faces a dilemma: should it maintain a regional focus, risking alignment with nationalist rhetoric, or return to universalism at the cost of reinforcing Western dominance? Going with the example of Hungary again, Viktor Orbán’s regime’s renationalization of cultural institutions (i.e. Magyar Művészeti Akadémia’s [Academy of Arts] takeover of Műcsarnok [Kunsthalle Budapest] in 2013) illustrates how state-driven cultural policies reinforce nationalist ideologies under the pretence of preserving heritage. András highlights that this shift is not simply a return to a past national tradition, but a restructuring of the present. This raises a critical question: How can post-socialist art history resist both nationalist instrumentalization and the pressures of Western universalism? Easternfuturism offers an alternative by rejecting both regional nostalgia and the expectation that post-socialist cultures must “catch up” to a singular, Western-defined development. Instead of situating itself within either a nationalist or universalist framework, Easternfuturism actively constructs alternative historical narratives, embracing speculative futures and nonlinear time to challenge rigid conceptions of progress and identity.

4. Easternfuturism: Counter-Narratives and Speculative Histories

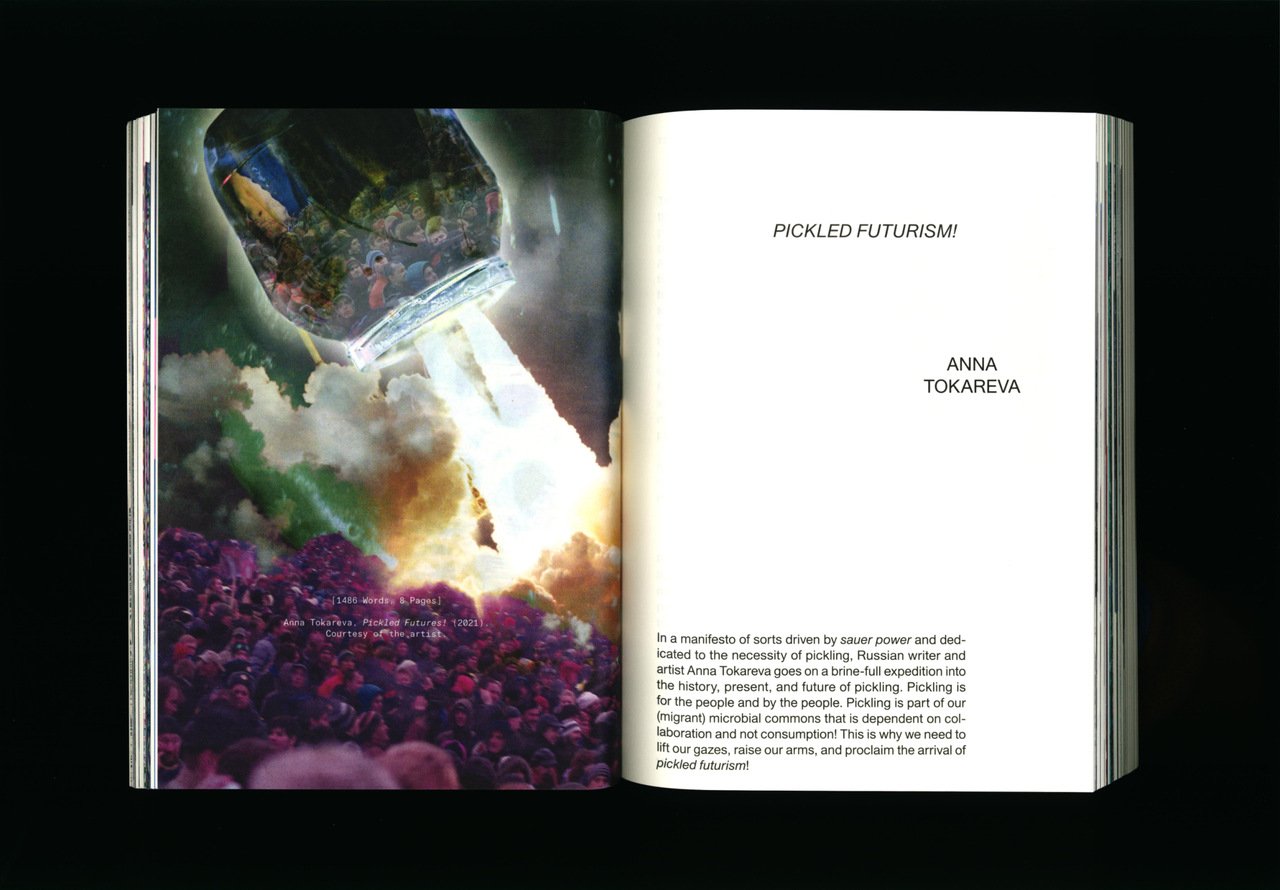

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, movements like Ethnofuturism arose as a way to reconcile traditional cultural elements with the modern world. Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, post-Soviet societies faced the challenge of reimagining their national identities, and navigating between the desire to reclaim lost cultural roots and the pressures of globalisation.[14]Easternfuturism emerged from this larger lineage of speculative artistic practices that were borne in response to shifting cultural and political conditions, engaging with the legacies of the avant-garde, modernist movements, and science fiction. Artworks engaging with Easternfuturism are not simply nostalgic or imitative, but they (re)interpret past artistic and cultural movements to address contemporary issues. A central theme in Easternfuturist practices is the “structural experience of absence” as a result of post-socialist transformations in which old urban spaces are forgotten, repurposed, or erased, mirroring broader societal shifts.[15] This is something that is reflected strongly in On Easternfuturism, which proposes that rather than longing for an imagined past, nostalgia can be transformed into an active and speculative tool for reshaping history. Easternfuturism also embraces diverse temporalities and cultural practices, from subcultures to mainstream activities, often involving space travel or video games. Video games are particularly relevant, as they offer an interactive platform where the users can operate within layered narratives in nonlinear timelines.[16] This reflexive (self-examining) and synthetic (combining different elements) process aims to create a rich, layered narrative that reflects the region’s complex cultural and historical landscape.[17]

Ukrainian photographer Pavlo Borshchenko’s series Sumy: Sorrow of my days (2018–2021), is featured in On Easternfuturism. This project explores the lingering Soviet presence for those born around the time of the Soviet Union’s collapse. His work questions what it means to inherit a historical identity without having directly lived through it, and highlights how this Soviet past continues to shape contemporary realities. Borshchenko uses his native city, Sumy (northeastern Ukraine), as a metaphor for the ongoing tension between past and future. Borshchenko’s images destabilize the idea of history as something fixed or fully in the past. In his images he constructs costumes for his figures from found objects – a pilot’s cap or an astronaut’s helmet paired with cardboard airplanes, ski goggles covered in red star pins, toy weapons, a blue Soviet era weighing scale. In one image, a chandelier is seen hanging above the head of a figure. It is attached to their back by a harness worn under their jacket. In others, the heads of figures are wrapped in patterned fabric that blends into their backgrounds. The landscapes in these images include open fields, snowy forests, backyards, and the gardens of half-built houses. These places often look empty or neglected, and in contrast, the figures tend to be wrapped in bright Soviet-era fabrics with colourful patterns that stand out against the more entropic backgrounds. In the indoor scenes, these fabrics are often draped across the walls. The faces of the figures are always covered, they are anonymous. These images are performative, blending everyday nostalgia with symbols of ideological authority. Borshchenko’s work reflects how memory, nostalgia, and futurity exist simultaneously by combining these Soviet era props and symbols in a surreal, often futuristic way.[18]

Another important aspect of Easternfuturism, also explored in this issue of Kajet, is the fact that it does not only reject or critique national myths but rewrites them, exposing their constructed nature. So, creating alternative national histories and identities by reexamining origin stories, archives, and myths offers more nuanced understandings of cultural heritage through speculative rethinking. This strategy is also central to Hungarofuturism, an experimental cultural movement that also emerged in the late 2010s and early 2020s, slightly predating Easternfuturism, which transgresses nationalist narratives through mythification and speculative fiction, aiming to develop a new, experimental cosmology and an “identity-poetical imagination.”[19] Zsolt Miklósvölgyi and Márió Z. Nemes describe Hungarofuturism as an aesthetic strategy of “mythification,” where historical myths are multiplied, exaggerated, and ultimately rendered absurd – a trait commonly seen in Easternfuturism – supporting a (possibly intentional) unified artistic strategy, where the theoretical and aesthetic forms can often be defined as non-essential and non-referential.[20] Rather than romanticizing Hungarian history, it operates within existing cultural and historical context, distorting it to reveal its contradictions and exposing the mechanism of nationalist storytelling. János Brückner’s short documentary Anyahajó / Mothership (2020) highlights the link between Afrofuturism and Hungarofuturism, demonstrating how speculative frameworks can reclaim history for alternative futures. Bringing these frameworks together in a shared dialogue is – while recognising that their histories are distinct – to explore a shared commitment to reimagining history, identity, and power structures through speculative means. Given that Afrofuturism has a strong foundational reference when it comes to liberated futures, perhaps it is inevitable that newer frameworks, like Hungarofuturism, engage with its strategies, adapting them to reflect their own cultural and political realities. This connection enriches the narrative by framing Hungarian cultural and historical reclamation within a broader, speculative framework of liberation and identity reformation.[21] By leveraging the Afrofuturist notion of the mothership, the documentaryunderscores the importance of cultural and historical memory.[22] This engagement involves questioning and reinterpreting past events, symbols, and figures to uncover their relevance and impact on the present and future, constructing new cosmologies and highlighting how speculative storytelling challenges fixed notions of national identity. We see this in Easternfuturism as well, particularly how it exposes the constructed nature of history, memory, and inherited identity. This is especially visible in Borschenko’s works, where the constructed, in-between identity is shaped by both the Soviet past and present/future.

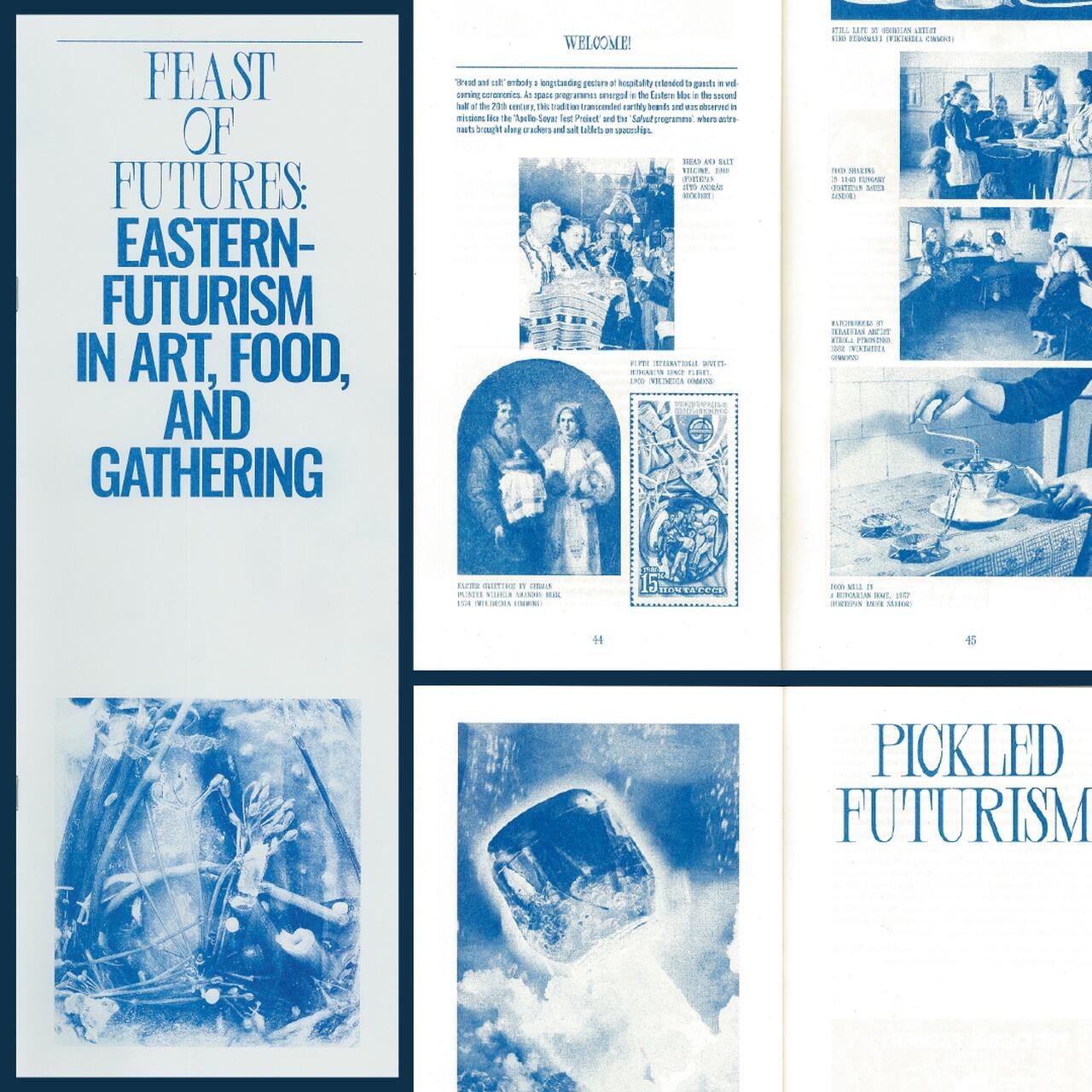

Another example is the October 2023 performative dinner hosted by Tanzfabrik Berlin, Feast of Futures: Easternfuturism in Art, Food, and Gathering, which utilized culinary traditions as speculative artistic gestures. The reimagined menu published for Montag Modus’s 2023 Archives of Futures III constructed an interlaced narrative space in which food-sharing and storytelling functioned as acts of speculative reimagination: the three-course dinner featured regional cuisine and family recipes, including pogácsa and pickled vegetables as starters, Kashubian naked noodles and turnip goulash as the main course, and desserts like wuzetka or nussecken. These dishes, drawn from different familiar Central and Eastern European traditions, are not only presented in a nostalgic way, but are recontextualized, displayed together to invite new connections between food, collective memory, and imagined futures.[23] The project worked with second-hand memories, including recipes and food traditions passed down through families. Some of these were collected from family cookbooks and archives shared by contributors (Kasia Wolińska, Léna Szirmay-Kalos). This focus on the translocal promotes new models of collaboration, highlighting that interconnectedness between regions, history, and nations.[24] In doing so, Easternfuturism is also about creating new ways of experiencing solidarity and togetherness. Feast of Futures underscores that in a time when national identities are increasingly built on exclusion and the demonization of cultural difference, reclaiming memory as a site of collective reimagination is a crucial political and artistic strategy.

5. Conclusion

One of the recurring issues in post-socialist contexts is the way history becomes either romanticized or politically manipulated – used as a nostalgic ideal to be reclaimed, or as a political tool to justify exclusionary policies. Easternfuturism is a way out of this: a form of temporal resistance, rejecting the linear progression of history that reinforces both Western-centric and nationalist, revivalist narratives. Instead of following a singular trajectory from past to future, Easternfuturism moves backwards, forwards, and sideways simultaneously and haphazardly, engaging with time as a fluid and multidirectional entity. Rather than seeking validation from dominant cultural narratives, Easternfuturism constructs counter-histories that emphasize interregional connections, translocal and periphery-periphery relations, and collective storytelling. By challenging fixed identities and static interpretations of history, Easternfuturism provides a flexible, inclusive, counter-narrative that acknowledges the complexity of post-socialist memory.

And so to conclude, I ask, in the spirit of Easternfuturism: how can we continue to develop a more inclusive art history and establish precedent for historical narratives and artistic practices, ones that do not rely on singular, linear interpretations but instead embrace multiplicity, fluidity, and interconnectedness? Can Easternfuturism serve as a platform for collective future-making rather than being trapped in the notion that history has already reached an endpoint? How can we construct new narratives that prioritize translocal connections over center-periphery hierarchies?

[1] Svetlana Boym, “Reflective Nostalgia: Virtual Reality and Collective Memory” in The Future of Nostalgia, (New York: Basic Books, 2001) p. 49.

[2] Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) is often used as a broad regional label across various fields, from economics to cultural policy and the arts. While it serves as a useful general term, it can also oversimplify the historical, political, and cultural differences between countries. I use the term here for practical reasons, as the examples I discuss are from multiple countries, including Hungary, Ukraine, and Romania.

[3] Petrică Mogoș and Laura Naum, “Editorial” in On Easternfuturism, eds. Petrică Mogoș and Laura Naum (Bucharest: Kajet Journal, 2022) p. 3.

[4] Svetlana Boym, “Reflective Nostalgia: Virtual Reality and Collective Memory”, p. 49.

[5] Svetlana Boym, “Nostalgia” in Atlas of Transformation, accessed February 16, 2025, http://monumenttotransformation.org/atlas-of-transformation/html/n/nostalgia/nostalgia-svetlana-boym.html

[6] A treaty signed in 1920 that caused significant territorial changes in Hungary, redefining its international borders after World War I, an event often exploited by nationalist populists for political rhetoric. See more: https://balkaninsight.com/2019/11/25/how-hungarys-trianon-trauma-inflames-identity-politics/

[7] Svetlana Boym, “Reflective Nostalgia: Virtual Reality and Collective Memory”, p. 50

[8] Svetlana Boym, “Reflective Nostalgia: Virtual Reality and Collective Memory”, p. 50

[9] Piotr Piotrowski, “On the Spatial Turn, or Horizontal Art History.” UměNí / Institute of the History of Art of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic., 2008. p. 378.

[10] Piotrowski, “On the Spatial Turn, or Horizontal Art History.”, p. 378.

[11] Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann, abstract of “Toward a Geography of Art” in Toward a Geography of Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004)

[12] Edit András, “What Does East-Central European Art History Want?” in Extending the Dialogue: Essays by

Igor Zabel Award Laureates, Grant Recipients, and Jury Members, 2008-2014, eds. Urška Jurman, Christiane Erharter, and Rawley Grau (Ljubljana, Berlin, Vienna: Igor Zabel Association for Culture and Theory; Archive Books; ERSTE Foundation, 2016) p. 55.

[13] András, “What Does East-Central European Art History Want?” pp. 60-62.

[14] Elvira M. Kolcheva, “Formation of Ethno-Futurism at the Turn of the XX-XXI Centuries,” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 6, no. 3 S7 (June 2015), p. 231.

[15] Daryl Mersom, “Now That the Future is No Longer Over the Mountain” in On Easternfuturism, eds. Petrică Mogoș and Laura Naum (Bucharest: Kajet Journal, 2022) p. 121.

[16] The relevance of video games are generally more discussed in connection to Afrofuturism. For example TreaAndrea M. Russworm explores how games offer a space for reimagining identity, power structures and cultural memory in “Video Games and Afrofuturism: Reimagining Black Futures in Gaming”, see more: https://jfsdigital.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/March-2022-Vol.26.3-53-70.pdf

[17] “Editorial” in On Easternfuturism, eds. Petrică Mogoș and Laura Naum (Bucharest: Kajet Journal, 2022) p.2.

[18] Pavlo Borshchenko “Sumy: Sorrowfuturism” in On Easternfuturism, eds. Petrică Mogoș and Laura Naum (Bucharest: Kajet Journal, 2022) p. 35.

[19] Ulrike Gerhardt, “Memories of Easternfuturism,” excerpt from Morpholgien der Transformation in postsozialistischer Videokunst (unpublished dissertation, Leuphana University of Lüneburg, Department of Cultural Studies), without references, p. 17.

[20] Gerhardt, “Memories of Easternfuturism”, p. 19.

[21] See documentary: https://vimeo.com/420714494

[22] Mia Imani Harrison, “Hungarofuturism and its Parallels with Afrofuturism”, contemporaryland, accessed February 15, 2025 https://contemporaryand.com/magazines/hungarofuturism-and-its-parallels-with-afrofuturism/

[23] Feast of Futures: Easternfuturism in Art, Food, and Gathering, curated by Lena Szirmay-Kalos and Kasia Wolińska, edited by Petrică Mogoș and Laura Naum (Berlin: Montag Modus, 2023), colophon

[24] Feast of Futures: Easternfuturism in Art, Food, and Gathering, curated by Lena Szirmay-Kalos and Kasia Wolińska, edited by Petra Mogoș and Laura Naum (Berlin: Montag Modus, 2023) p. 21.