A Conversation between curators Oona Doyle and Agnieszka Szewczyk

Oona Doyle: We have been working together to curate this exhibition, the first major solo presentation of Teresa Pągowska’s work in London. Can you tell me about your first encounters with Teresa’s work in Poland?

Agnieszka Szewcyzk: Teresa Pągowska is a well-known artist in Poland; she is a classic figure of post-war painting, represented in public and private collections, but at the same time, I have the impression that she is somewhat forgotten. She has her place, and few people try to look at her work in a new way.

I came into closer contact with her work shortly after she passed away in 2007, when I was organising her archive and oeuvre. When I came in close contact with her paintings, with all that was left in her studio – she worked until the very end – I immediately understood what a serious painter I was dealing with.

I worked for many years at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, where Teresa was a professor of painting since the 1970s. So I knew her work a little better than most art historians of my age for whom she was already a classic, known more from books on the history of painting than from real contact with her works.

But to tell you the truth, I started working on her archive because I was researching the archive of her husband, the eminent graphic artist Henryk Tomaszewski, because I have always been interested in graphic art and was planning to prepare a large monographic exhibition of Tomaszewski and a book about him.

Tomaszewski died in 2005 and Teresa at the beginning of 2007, and I had the opportunity to enter their home after they both passed, and for one and a half years organize, both archives. It’s a very special kind of work that gives deep insight into the artist’s work.

But it was only after a few years, when the methodology of art history was changing significantly, that new research appeared, and new perspectives on art emerged. The art field became much more divided, and it was then that I understood how much the discourse accompanying her work has stagnated and become concrete, or “set” in this linearity from post-war colorism to Informalism to New Figuration, encapsulated in immortal phrases about (mostly male) influences and inspirations. This traditional narrative situates Teresa’s art, so to speak, outside of herself, and completely obscures the originality, strength, and certainty of the path taken by this very determined, conscious, and independent artist.

That’s why I was so pleased to work with you, Oona. Your perspective on her art is completely different and very in-depth. What interested you in Teresa’s art? How did you come to know her work?

OD: I did a traineeship at the Tate for a year where I helped with research on post-war and contemporary women artists from Eastern Europe. Some years later, I read an article about Teresa Pągowska online in The Calvert Journal (published by Calvert 22, a London-based non-profit dedicated to promoting young and emerging talent from the New East), which shows the importance of journalism! I was immediately struck by the singularity of her painting. I like the fact that her work is not especially reverential to preceding the “great masters” or that it is in voluntary conversation with art history. I see it as more rebellious and groundbreaking in a way. It seems that she developed her very own language through acute observation, deep introspection, and experimentation.

I hadn’t seen anything like it before, especially the radical use of raw canvas as a pictorial device. Shapes and bodies emerge from the actual material of the canvas. I find it very clever, her play with negative space. The linen evokes skin while it also gives the figure mystery; a more elusive, intangible quality. What can you tell us about this particular characteristic of her work and also how she experimented with materials?

AS: Teresa paid great attention to the technical side of her painting, and although she remained a fairly traditional painter in terms of technique, she developed a very sophisticated approach. She also developed her own discoveries and ways of working, such as those we see in the Monochromes series.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, Teresa had two exhibitions at Galeria Współczesna, a then-important gallery in Warsaw. She showed great paintings there, but she didn’t get any reviews or reactions from critics. It was a disappointment for her because they were great, strong paintings. I think that’s when she decided to radically change her art, to completely abandon colour and limit her palette to monochromatic colours. That’s when she started using the expression of the unpainted, raw canvas, just as you mention. That’s when negative spaces appear in her paintings. This “restriction” resulted in a completely different type of painting, a different way of constructing the figure.

Teresa began to use stencils cut from craft paper and pinned them to the canvas and then painted. With these stencils, she sometimes multiplied shapes and figures, as in the 1978 painting Magic Group II shown at the London exhibition. This new series of works provoked quite a violent reaction from critics and other artists. They did not understand her idea, they thought that these paintings were perhaps unfinished. But this fortunately did not discourage her, she was very conscious of what she was doing. She trusted her choices and believed that the worst thing would be to fall into a routine, to become a “specialist” in some field. She liked to experiment, she liked to struggle with the painting. She would say that “every painting starts as if I knew nothing about painting.”

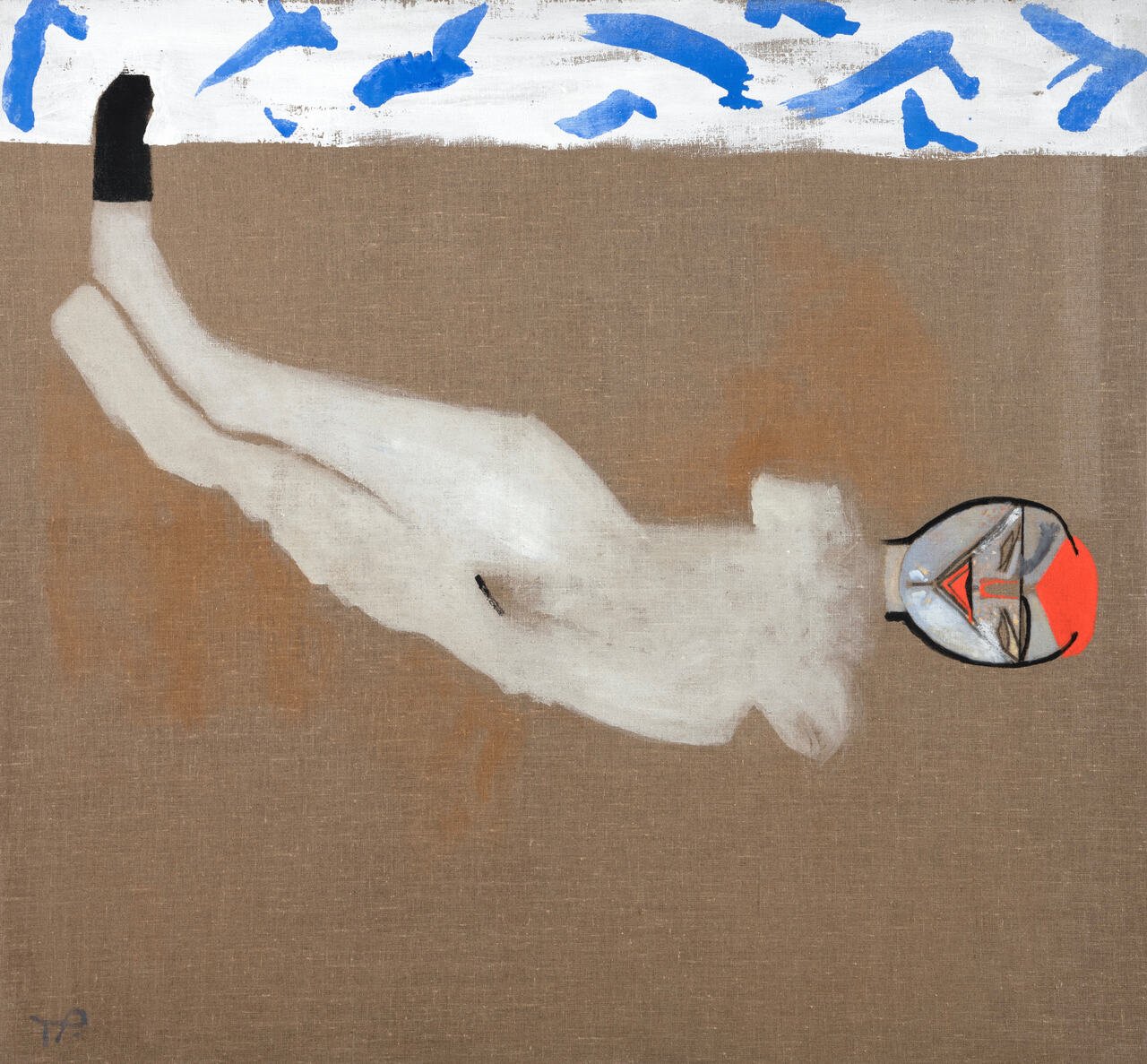

OD: Yes, I also love the quote where she says, “I constantly go wrong, miss my aim, struggle with the canvas, which is both my greatest enemy and my dearest friend.” In the exhibition, we are presenting Beach in the rain, from her Magic Figures series (1978) and Monochrome XXXXC (1975). Thanks to your research in the archive, we could include some very interesting material that shows her creative process. Could you tell us more about some of the discoveries you made?

AS: Teresa left behind an extensive archive and workshop in Warsaw. Thanks to this, we know that she didn’t actually make sketches for paintings. She was inspired by what she saw. She had a very sharp sense of observation, she liked to observe people on the beach, for example. She observed nature and animals with great sensitivity and then transferred her ideas immediately to the canvas.

OD: She was working from memory and sensations. It’s not photo-based like a lot of painting secretly is. Although she did source shapes from found images.

AS: Yes, images seen according to her reality were always filtered through her imagination. She would also cut out pictures from newspapers and magazines that interested her – motifs, shapes, landscapes. We have a large collection of such clippings that inspired her. This is very interesting and important because it allows us to have an insight into her aesthetic sensibility. The materials we display in the vitrines in the exhibition reveal a bit about her process. They show a sustained attachment to certain motifs. Additionally, they reveal that the traditional order of painting, first a sketch on paper and then a painting on canvas, was reversed in Pągowska’s case. The work on paper with the zoic female figure that also appears in the painting Monochrome XXXXC was created many years after the painting.

OD: I like this idea of using what is at hand and using material as image rather than imposing an image: raw canvas, found paper. The image surfaces from the material like an apparition. It conveys this idea she shared of “expressing everything with nothing.” There is this interesting work where she repurposed paper from a Japanese magazine to paint her figure. The paper features an article in English and Japanese where they mention female icons in art such as Marylin Monroe and Mona Lisa. These laid out letters and characters of varying lines add to the pictorial quality of the work and contribute to its dynamism, and there is an interesting chance encounter between the image and the subject of the text.

AS: Yes, she had a tendency to reuse materials: wrapping paper, newspapers, flyers – materials that already have some “history” in them and are not “perfect.” Her works, including paintings, especially from the 1960s and early 70s, are built like palimpsests: layers of paint obscure what was painted underneath, the final image is built through the layering of material and meaning.

OD: Another aspect of her practice that really struck me was the way she paints the female figure, which is central to her work. There is a lot of discourse around countering the male gaze, but it’s hard to undo representational canons. She has a very felt and liberating way of painting the female figure. Teresa’s figures adopt shy, erotic, anxious, or dancing poses. At times they seem to metamorphose before our eyes. MoMA PS1 curator Connie Butler characterized Pągowska as a proto-feminist, as she is one of the first Polish artists to consciously address the subject of the female body, “working prior to a feminist discourse,” alongside Alina Szapocznikow and Magdalena Abakanowicz. Could you tell us what you think of her link with these artists, as well as Teresa’s role in the Polish scene of the time and context?

AS: Yes, Teresa said, “What occupies me most profoundly is the human figure. Not only because of the richness of form. I think that it is the human body that contains the most content-related magic.”

All of these artists have in common that they have developed their independent artistic languages. They talked about the experience of the body and femininity in their own ways, they found their own languages. The juxtaposition of Pągowska and Szapocznikow is interesting to me because I have the impression that they have a lot in common. One of the key concepts for understanding Szapocznikow’s sculptures – the imprint, the trace of the body – is, after all, an equally important motif in Pągowska’s paintings, with these negative spaces and the way the figure is built, for example in Monochromes. It is as if someone got up from the painting and walked away, left a space in it, a trace on the canvas. What they have in common is their sensitivity to the dynamics of the human figure, and treating the body as matter charged with emotions; sometimes defective, always transforming.

OD: Teresa was a teenager when the war started in Poland, a country that went through two occupations, first under Nazi Germany and then under the Soviets. In some of her works, the body is fragmented, even dismembered, like in Untitled (1969) that shows a woman crucified, or Magic Group II (1978). Pągowska’s visions might also allude to the unrepresentable trauma in the postwar context of Europe, conveying sensations of a hurt body, or feelings of disruption through her cut-out shapes. There is this feeling of imperfection and thus, humanity.

AS: Yes, it seems to me a good and very important intuition. No one paid attention to it before. Teresa did not talk about her war experiences, although the war years occurred during her adolescence. For a girl and then young woman, raised without a mother, and whose brother was murdered in Auschwitz, it must have been a very difficult and somehow crucial period. The loss of her brother in particular, his absence, haunted her for years. We see this in the Monochromes series, where we often have the motif of a dismembered figure, a body, and sometimes a perceptible emptiness, a trace of someone who is gone.

OD: There is a sense of loneliness in many of the paintings. One of my favourite works of hers is titled Alone. Could you tell us more about the cultural context of Poland at the time? Was she influenced by theatre, cinema, politics? Which books and writers were important to her?

AS: In the mid-1950s, following both Stalinism and Stalin’s death, Poland opened up much more to the Western world. There was also an explosion of creative activity; great cinema, literature, and contemporary music. Among the close friends of Teresa and her husband, Henryk Tomaszewski, were many artists, architects, filmmakers and writers. Close friends included the great writer and director Tadeusz Konwicki, as well as Andrzej Wajda and Jerzy Skolimowski. Teresa traveled a lot, which was quite unusual for the Communist era in Poland. She was always visiting exhibitions of contemporary art and also subscribed to Art in America, an important magazine at the time. She certainly liked to know what was going on around her and was interested in art not necessarily similar to her own. She also seemed to have quite strong opinions on various subjects.

OD: Would you say she is part of the avant-garde?

AS: Yes, certainly a part of avant-garde painting in the historical sense. She was influenced by Informalism in the 1950s, like the majority of painters of her generation, and later by New Figuration. She exhibited a lot, was involved in organising exhibitions, and also curated several editions of a large survey of contemporary art in Poland.

OD: I am interested in her particular sensitivity to her surroundings, notably nature: her astute observation of the horizon line and how it structures our world, the way she renders the colour and texture of sand using the materiality of the canvas itself, and her love of animals, which at times, are fused with human figures. What role do you think animals play in her paintings? There is something about her interspecies, hybrid figures that make her almost contemporary.

AS: Nature and animals were very important to Teresa. She liked and needed close contact with them. She cultivated a garden, grew beautiful roses, and there were always dogs at home, who were much more than just pets. They appeared in her paintings and drawings. She dedicated several paintings to one of her beloved dachshunds, Patek, when he died. I don’t mention this to expose her sentimentality, but rather to show her really special sensitivity to nature. She had a kind of solemnity in this; Teresa was not a religious person, but I have the impression that her attitude to nature was deeply spiritual. With time, more and more such motifs appeared in her works. The human figure ceases to be depicted in interiors and begins to appear in nature. There are more landscapes, works with a deep relationship between the figures and the natural surroundings.

OD: In some of the paintings, by featuring figures in the negative, Teresa almost inverts the anthropocentric focus that has so long characterised the anthropocene, giving importance to its surrounding environment and fauna and leaving the human in negative, as a silhouette.

AS: Exactly, this is undoubtedly an important interpretive track. Here, Pągowska was a pioneer! We have selected a wide variety of works for the exhibition, from different periods of Pągowska’s career, so that viewers can see the diversity of her practice. However, there is some consistency in it, wouldn’t you agree?

OD: Yes, with her acute sense of colour and the work’s enigmatic qualities, I find it interesting how her figures are always merging with the environment, expressing the idea of a porous boundary with their surroundings. In her practice, there are elements that reference our shared reality, but she also leaves room for a certain liberty; space for imagination and transformation.

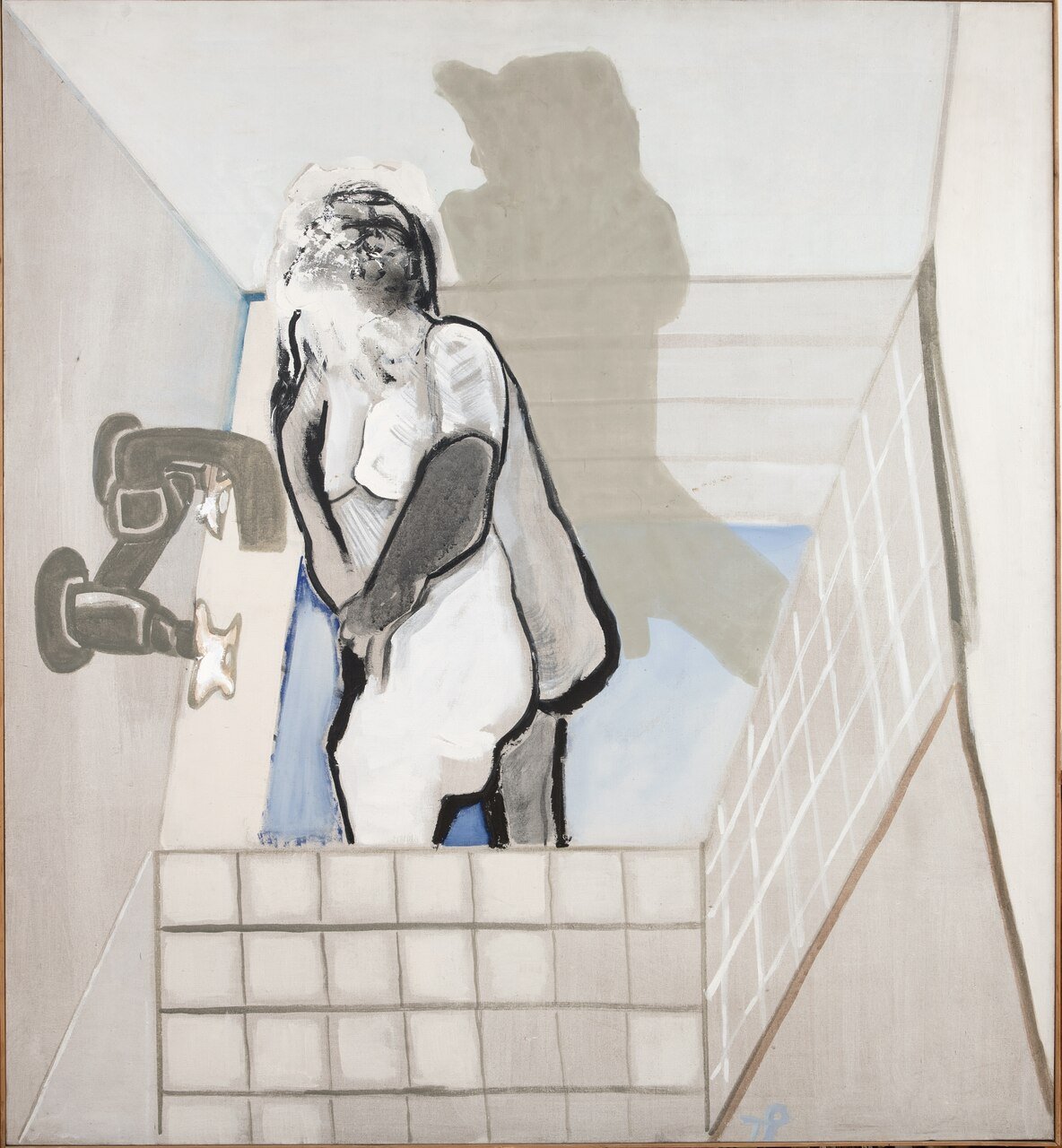

Her paintings seem to also express the experience of a female self, rather than the objectification of a body or the representation of a figure for its social role. Kapiel (1974) captures the intimacy of a woman under a shower. However, she is not hypersexualised. Her pose is closed in on itself, it’s somewhat realistic and relatable. And there is this intriguing shadow that could either be a liberated dancing version of the figure or a menacing presence.

AS: Right, this painting is somehow disturbing – an effect of the disturbed geometry of the space, the juxtaposition of the “realistic” bathroom with the expressive treatment of the female figure and the strong presence of the shadow. For me, there is a palpable presence of another person in it. The form of the shadow is very dominant and strong, it does not repeat the shape of the bathing figure. Although of course, the painting should not be taken so realistically.

OD: Yes, her works are full of these ambiguities. They are semi-abstract and very open, full of possibilities and dream-like insights. You take time to look and interpret what is happening and a lot of works are amorous, as if there were two bodies in one, or maybe they are just a Gemini, one person with two different selves? This notion of the double does seem to punctuate her work. In Kapiel, we can decipher another figure behind her in addition to the shadow. In Untitled (ca. 1987), if you look closely you can see two heads kissing or merging. The arms are multiplied, which adds movement – they look like wings. This simple female figure with a black dress becomes an angel of sorts. There is something very poetic about her work, transforming a simple walking girl-figure into a winged being that perhaps actually contains two figures.

AS: Yes, which brings us to the title you suggested for the exhibition. Could you tell us more about this idea of a “shadow self” in her work?

OD: Since it’s Teresa’s first solo exhibition in London, we wanted to include key works from different periods. The exhibition spans 50 years of her practice. When looking at the works, I noticed that she used shadows a lot. It is a formal device which allows her to pictorially link the figure and the ground, the human body and its environment. She has a series of works which she brought together around the title Magic Group. In these works, the play with negative space and light and shade creates magical inversions between containing and being contained, where sometimes the figure is empty and the surrounding is coloured. It produces the sensation of movement and transformation.

The shadow is also a way to give her figures depth and duality. What is interesting in her works is that shadow has a life of its own sometimes, as if it was a liberated version of the self or a fantasised self. In other works it seems like a menacing presence. There is an introspective quality to her works, and these traversing shadows add to the sense of mystery. There is an interesting dichotomy between being seen and hiding in her paintings, which I think is very relatable.

AS: You have brilliantly noticed the importance of shadow in her painting, it could indeed be one of the leading motifs of her art. Also, in a more metaphorical sense, because of course her art is not autobiographical in the simplest sense of the word, but at the same time it is very strongly marked by her way of feeling and experiencing the world. I feel her presence, her shadow, in her works.

Artist: Teresa Pągowska

Exhibition Title: Shadow Self

Curated by: Oona Doyle, Agnieszka Szewczyk

Venue: Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery

Place (Country/Location): London, UK

Dates: 14 .02. —2. 04. 2025

Photos: All images courtesy Teresa Pągowska Estate and Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London ·Paris ·Salzburg · Milan · Seoul.