A conversation between Monika Gabriela Dorniak and Silvia Russo

In the summer of 2023, I had the opportunity to visit the studio of interdisciplinary artist and researcher Monika Gabriela Dorniak, whose artistic research is often characterised by the use of evocative materials, such as stones and blood, alongside the profound themes that animate her work. During our encounter, a particularly significant moment emerged as we observed a ceremonial dance of swallows flitting above her balcony, prompting deep reflection: how would we see the world if we were birds? The following interview unfolds in an essay-conversation format, resulting from the collaboration between Monika and myself within the framework of the Seduta Artistica[1] curatorial sitting, which aims to focus on the artist’s free and personal creative expression, creating a space for dialogue in which we reflect on crucial issues within contemporary discourse.

In the German-Polish artist’s practice, connections evolve that blend her working-class and post-migrant background with a decade-long study of intergenerational trauma. Monika’s work adopts an ecofeminist lens, valuing more-than-human agencies as integral to the broader experience of existence. However, confining this introduction to just these concepts would be reductive, as our dialogue opens up in multiple directions.

Her artistic research, which incorporates ritualistic practices, acts as a form of resistance against our fast-paced society, highlighting the importance of collective memory as well as intergenerational and interspecies relationships. As Donna Haraway observes, we are witnessing a transition from the Anthropocene to the Chthulucene, where all living beings’ interconnections are embraced. In this framework, Monika emphasises how trauma does not reside only in human bodies, but is also embedded in the fabric of our ecosystem – landscape, rivers, forests, and beyond.

The dialogue we shared, rich with insights and reflections, lingers in my thoughts, inviting further contemplation on the intricate constellation of relationships that shape the understanding of ourselves and the world we inhabit.

Curator, Silvia Russo

Silvia Russo: I’m interested in your artistic exploration of temporalities and localities. You’ve deeply engaged with the subjects of trauma, non-linear time, and intergenerational memory. How do your personal experiences and family history shape your understanding of these “past remnants,” as you call them, that transcend temporal boundaries?

Monika Gabriela Dorniak: My German-Polish embeddedness immersed me in an auto-ethnographic “noise” – a term I am adapting to this context from Avgi Saketopoulou and Ann Pellegrini’s Gender Without Identity (2024). Their psychoanalytical work analyses how the theorisation of the Self and the intrusive impact of others shape us, using gender and sexuality as examples. In my example, I often felt as if my own memories were overshadowed by external constructs and memories that the war evoked, creating a rigid and strangling system of a singular national identity that, as a bi-national person, I felt no belonging in. Despite my German side of the family having mostly resisted the Nazis, the constructed way of how we ought to remember and recall WWII has not really allowed me to mourn the losses of other people, nor the landscapes, that were barely mentioned in the German history classes on WWII in my youth.

The complexity of remembering, or its inevitability, as Marianne Hirsch suggests in The Generation of Postmemory (2012), has been central to my artistic practice. This focus has been particularly evident in my exploration of World War II-related intergenerational trauma, which I began immersing myself in more than a decade ago.

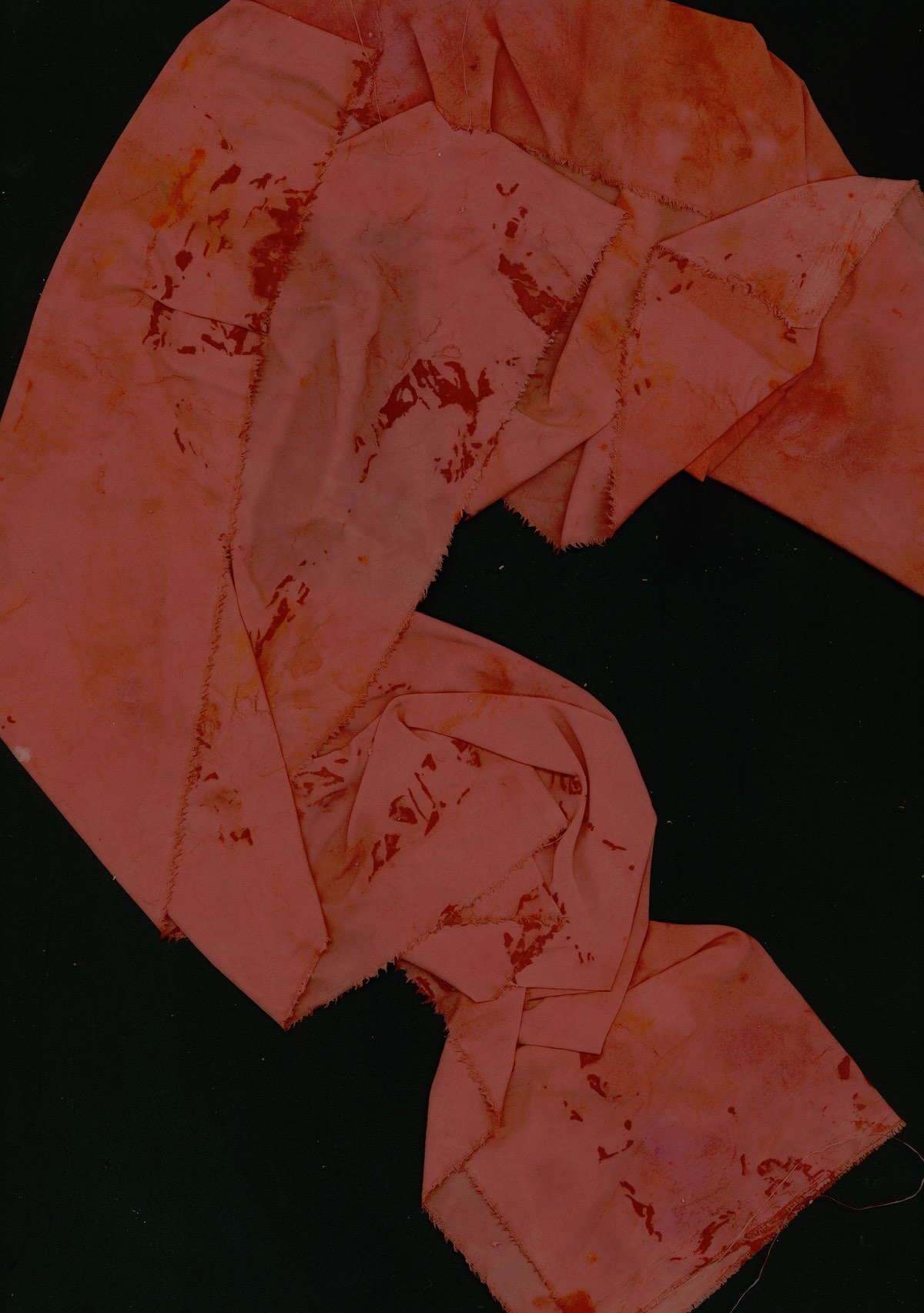

In my first solo exhibition, Human Anatomy is Adorning Itself (2011), I presented a selection of works, including a zine, photographs (partially self-portraits and a collection of images from the Flickr community in which I was involved at that time), dia projector slides of a lung (from my mother’s nursing training), and textile sculptures (which I referred to as wearable sculptures, as they also appeared in my video performances). The installation took place at Alex Xie studio (formerly Galerie Micky Schubert) on Oranienstraße during the Das Weekend festival, which was organised by Kunstverein Neukölln. Between my fashion design studies and my psychology studies, I created this series of wearable sculptures, which I considered representations of the multiple layers that constitute my identity. It was akin to a psychoanalytical process, in which I rearranged these parts of myself and stripped them away to perceive them from a distance.

In 2013, I encountered two critical texts that helped me further understand certain feelings and sensations that lingered in my bones: an article on trauma research with Shoah survivors’ descendants, and Shanaaz Hoosain’s application of these findings to historical trauma from colonialism, apartheid, and slavery. These texts, which I encountered during my psychology and performance studies, inspired my auto-ethnographic work explored through various projects between 2013-2023. This work was also further influenced by encounters with critical researchers like Alva Noë, whose neuro-philosophical and somatic theories – developed in collaboration with dance practitioners – place memory in the body rather than the brain. These ideas have been particularly significant for me.

Growing up between Germany and Poland, I sensed WWII’s ghosts in my present, that often did not allow much room for other issues, such as questions on gender and sexuality. Over the past decade, I’ve used art to dissect and reconnect the ethical, socio-cultural, political, and scientific layers of my family’s war-related experiences of resistance, scarcity, and displacement, as well as the linked patriarchal violence. I’m captivated by how violent experiences echo anatomically through generations, anchoring in bodily and earthly cartographies – but also how some experiences turn into imaginations of victimhood that distract from other inequalities.

My ancestral and personal trauma experiences have taught me to understand and directly experience time’s non-linearity, applying this insight to my practice and life. In my Eurocentric education, the past was often portrayed as a rigid, linear archive – a view that contrasted sharply with my German grandmother’s unwavering dedication to Hildegard von Bingen’s faith and practice of a bodily, divine spirit. This perspective also differed from the paganistic traits I occasionally encountered beneath the Catholic veneer of my Polish family. My Polish aunt would share fairytales with me every night, featuring Slavic pagan spirits and gods that inhabited the world around us. In these stories, the living and the dead were not separated but engaged in constant exchange – a theme present in both my German and Polish family histories. In my work, I regard such “past remnants” as companions in our present, transcending constructed temporal and spatial boundaries.

Our pluralised societies harbour coexisting times and localities, many with traumatic anchors. Today’s wars trigger symptoms like anxiety, anger, and alienation. Currently, we are witnessing the consequences of inadequate historical representation and recognition on a global scale, along with the enduring impact of past traumas. On an ancestral level, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 made me realise that the few cultural archives surviving World War II were again at risk – evoking existential fear as the scarce material and embodied memories from my grandparents’ past once more faced potential erasure. Recently, I came across an interview with author Annie Ernaux on Louisiana Channel, where she states, “Memory is my instrument and my element, my material.” This resonates deeply – in my work, I strive to liquefy rigid, biassed historical archives and introduce new potential versions of the past from silenced perspectives. The notion of freely choosing memory as a medium and research subject may seem questionable, especially given my personal experiences with trauma and memory loss. Yet, over time, I’ve found ways to transform memory into a liberating force, freeing me from the past rather than letting it overwhelm me.

SR: As we transition from your past to the present through an intermediate process, I’d like to explore the concept of temporality more deeply. The perception of time is a central and widely debated issue in our fast-paced society, which prioritises what it deems “useful” while trying to eliminate the “useless.” I’m reminded of Susan Sontag’s assertion: Time exists so that everything doesn’t happen all at once. In this context, I believe your artistic practice challenges the postmodern view of temporality and time experience. Would you like to discuss the importance of rituals as a form of healing for the mind, body, and our collective memory?

MGD: As an artist, I believe that one needs to create one’s own temporal system. The ability to act within one’s timeframe deeply impacts our cognition and thinking, and provides new perspectives towards our inner and outer worlds and histories. For me this is certainly a privileged position to be in, considering that my working-class families were bound to time frames that were dictated from the outside. The work Feminist, Queer, Crip (2013) by Alison Kafer, which I learned about through Cathryn Klasto’s generous teachings, has helped me to further reflect critically on the inaccessibility of time within our accelerated systems. As a disabled and chronically sick person, one is being given less opportunities to participate in the arts, which consequently impacts the recognition of artists to whom the above conditions apply. Rather than considering “crip time”, as Kafer calls it, as something extraordinary, disabled artists are calling for their normalisation within institutional frameworks. As a crip person myself, a regular practice of personal rituals, and thereby a creation of my own time, is necessary for me to be able to work. It takes effort to find these rituals.

To establish routines, I revisited my ancestral connection to spiritual and labour practices and critically examined them in 2016. Growing up in a 600-person village, with very limited access to culture and arts, one faces moments of boredom, which have become rather rare in my current, mostly urban life. On my German grandparents’ farm, I was often involved in hands-on practices. These were labour-intensive but also provided an opportunity to enter a repetitive state that calmed the nervous system. At the same time, this village was rooted in very patriarchal and conservative concepts, which were interwoven in certain rituals. What Silvia Federici describes in Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation (2004), still applies today: the knowledge of peasant women is often not considered equally worthy, and the closer connection to the land and their other-than-human agencies is being ridiculed by the male villagers. Remembering this as a mental footnote is an essential part of accessing and revisiting traditions to avoid a repetition of violence, extraction and power-imbalance.

My grandfather’s labour in the forest provided us with wood that was required for heating and cooking for some time – but I claim that it was also a form of subconscious therapy. On the one hand the forest confronted my grandfather with the remnants of war, mostly in the form of bomb splitters, on the other hand it continued growing, despite the painful events that he associated with it. While human trauma is usually considered as a static, unrepairable state, the forest can, despite its implicated-ness, function as a reminder for a transformed ongoingness.

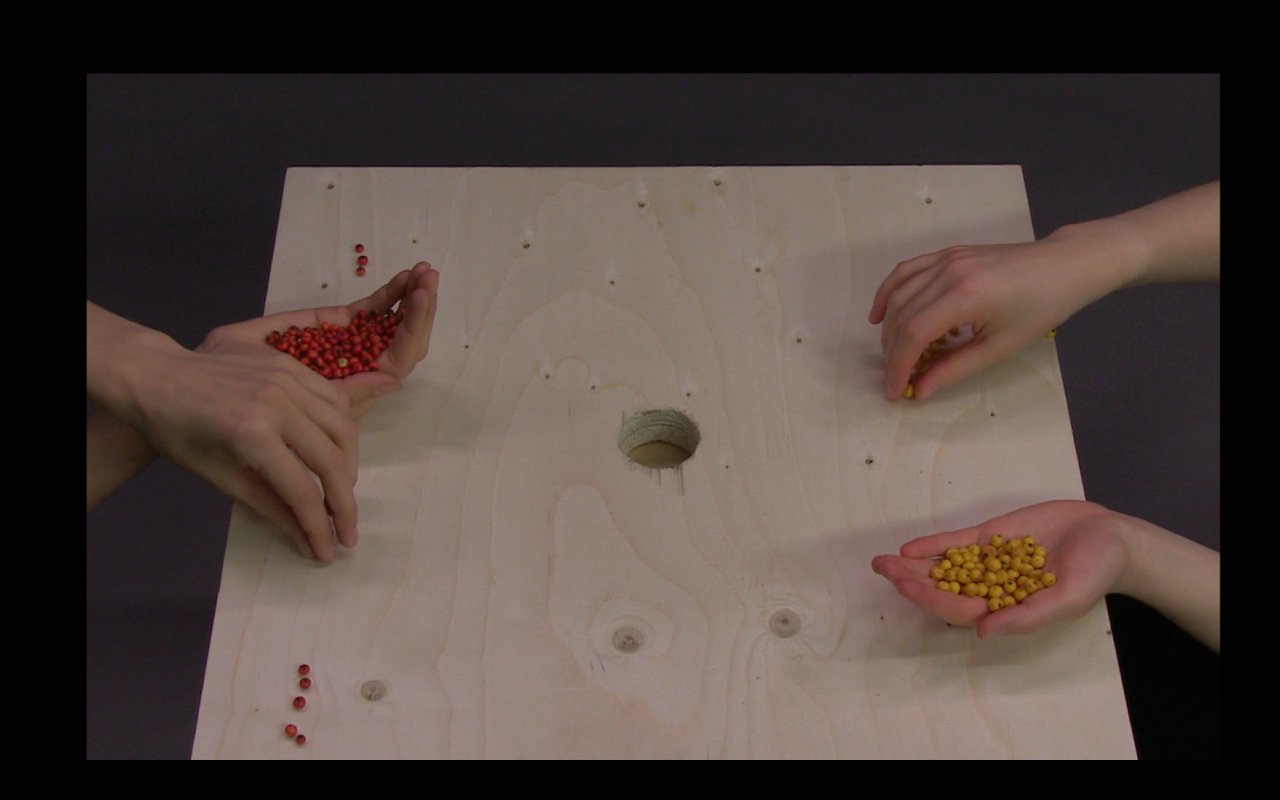

The works Un/Folding (2015) and Metacognitive Tool (2016) which I created in London as part of my hand-sculpture series, aimed to document and perform my bodily archive of gestures inherited from my family. While Un/Folding focuses more on the monotonous acts of harvesting that I engaged in throughout my childhood in the countryside, Metacognitive Tool was focusing on reclaiming the body as an anatomical entity. This work references Laban’s principles[2] and a neuropsychological theory that underscores the importance of metacognition – thinking about one’s own thinking – as a means to influence neurological processes. The series was presented at the exhibition Remember Nature at Central Saint Martins’s “The Street” initiated by Gustav Metzger and curated by Alex Schady. It was a tremendous honour that I had the opportunity to discuss the works with Metzger, who was deeply moved by them.

Walks, and other forms of hands-on practices, are nowadays also used in the arts and institutions. Many rituals that my grandparents practised were born out of a place of scarcity, and in some cases have nowadays turned into exclusive artisanal practices which partially exclude those who may need them the most – this class tension is something that concerns me. Providing recognition to groups that have for a long time been made invisible is important – however, I also wonder whether a de-contextualised and short-temporal application of these rituals in a fast-paced-institutional environment is able to act as a substitute for long-lasting connections between people and practices, especially when the conditions of inflation make it even harder for certain groups to enjoy arts and culture. I would claim that rituals require repetition to become meaningful, and this repetition requires trust that first needs to be established. For instance, annual rituals, such as the hay harvest, were always embedded in social constructions of trust and commitment.

The farms in Habscheid, where I grew up, supported one another through material and labour exchanges. I would claim that their act of harvesting was not merely agricultural; it involved celebrating the harvest by eating and drinking together the food that was produced, such as bread and soup – which was again linked to ritual and ceremony. The woven relations between these hands-on acts provided people with a sense of stability and created a foundation for care and connection to the environment. It is important to note here, that the care work was generally performed by local women who were usually exploited in these contexts, and tasks were usually divided by conservative gender roles. Ultimately, the environment always dictated the rhythm of these rituals – as farmer families, we needed to know the subtle changes in weather. If one ignored a sign of potential rain carried by the winds, an entire year’s harvest could be destroyed within a minute.

SR: Do you consider your rituals to be healing practices – both for yourself and, potentially, for others?

MGD: I am cautious of using the word healing in connection to my practice, as I myself am not a medical practitioner – I consider my works as practical gestures or poetic inscriptions that can be applied and activated. As someone who has experienced traumatic events, I understand that the body cannot simply heal and return to its previous state. Instead, we must learn to adapt to a new reality. Rather than focusing on healing, I prefer to view my practices as opportunities to de-stigmatise and challenge both individuals and institutions. We need to address how people with disabilities are still excluded from many spaces. Instead of labelling their needs as “special” – as Kafer critiques – I hope that institutions and society at large will broaden their definition of normal to encompass diverse perspectives that may differ from their own.

In recent years, I have produced a variety of scores, partially in collaboration with sound artist Monty Callaghan, such as Your Body Is A Water Vessel (2022) which have been inspired by my choreographic work and also my research in psychology, biology, and Astrida Neimanis’s work on hydro-feminism. The auditory score for Your Body Is A Water Vessel actually derived from the performance piece I mentioned earlier, Metacognitive Tool, in which I focused on the biological theory that all human beings evolved from a creature called Pikaia, which is believed to still inhabit the deep sea today. This organism is primarily composed of a spine, which enables movement, and exhibits similarities to the human spine. In this work I explore the positive effects of “past remnants,” reminding us of a state in which our senses served as primary guides rather than being overshadowed by the complexities of human consciousness. In Your Body is a Water Vessel, the listener embarks on a journey with the voice, confronting painful events while simultaneously finding a way to distance themselves from themselves, inviting a reconnection with our primal, animalistic selves.

The reflections that I share in the scores have appeared useful for me, and I enjoy offering them as open-source files (outside of institutional frameworks) to people who may need them.

SR: The concept of ritual is fundamental to understanding how art can serve as a tool for healing, a deeply personal process rooted in individual experience. For instance, ritual practices and traditions, transmitted from generation to generation, serve as witnesses to our resilience over time and resistance to our society. However, in addition to these rituals and traditions, there is a deeper transmission: the transmission of genes that shape our biology and identity from birth, challenging the idea of the “clean slate”.

One of your latest projects, Passing on Resilience (2023), aims to explore the concept of trauma in the context of post-Soviet countries, focusing on its manifestations in contemporary bodies and landscapes in Lithuania and surrounding regions. I would love to hear more about it.

MGD: My works function as interconnected maps, some focusing directly on research while others – such as audio-visual scores, sculptures, and workshops – serve as puzzle pieces that inform and build upon one another. One of my first projects addressing intergenerational trauma was Uprootedness & Hybridity, a commission by the London-based organisation Counterpoints Arts in 2021. For this seminar series, I invited interdisciplinary practitioners[3] to examine transgenerational trauma while considering transcultural solidarities as a form of resistance.

Passing on Resilience was curated at the National Gallery Vilnius in 2023, in partnership with the Goethe Institute Lithuania. We explored the impact of post-Soviet trauma on contemporary bodies and landscapes in Lithuania and its surroundings through various modes – discussions, workshops, creative activities, and, importantly, communal meals. Simultaneously, we drew connections to Afro-European post-colonial experiences. Rather than viewing it as a static programme, I perceived the initiative as a choreography, inviting the audience and participants to engage with the subject through a multitude of senses.

Addressing this subject in Lithuania presented a new challenge, as the country’s involvement in World War II events has not yet been thoroughly processed. The violent historical events and subsequent long-lasting oppression have led to polarisation and division, as in many post-Soviet countries.

During my first research visit to Vilnius, I was shown a map commemorating the numerous Jewish villages and their 190,000 Lithuanian-Jewish inhabitants which had been erased. Surprisingly, I learned that some former Lithuanian partisans, viewed as heroes in the struggle against Soviet occupation, continue to preserve and re-erect statues or monuments of Nazi collaborators. Despite the difficulty of addressing this subject in such a divided context, we aimed to bring people together to share their perceptions and memories. Food served as a connecting experience and valuable theory – Jewish heritage remains noticeable in Lithuanian cuisine, while memories persist of Nazis bringing sweets and chocolate and persuading poor peasants to view them favourably. Among the participants was Prof. Dr. hab. Danutė Gailienė, who has extensively researched the subject of intergenerational trauma since Lithuania’s liberation after 1990-1991. Our conversation as part of the program left a lasting impression on me. She emphasised the importance of considering the complexities associated with resilience. While our society often views resilience as a positive attribute, there’s an overlooked burden that comes with it. I believe resilience grown from traumatic experiences, or inherited trauma, can also lead to a dissociation from feeling one’s own or another’s feelings. As a post-migrant child raised by a single working-class mother, I felt resilience was my only path to survival. I’d argue many working-class and/or (post-)migrant families face the same dynamic: either learn to work hard and push feelings aside or struggle to pay the bills.

The project title Passing on Resilience encompassed two key dynamics: we explored the aftermath of trauma while also acknowledging the challenges this poses for many societies today. For the project I invited, amongst others[4], the artists Jonas Palekas and Michał Jurgielewicz to collaborate on a new artwork, which they named The Practice of Airing. Through several hours of Zoom meetings we reflected on the subject and combined ideas of assembling and fire-making – present in Jurgielewicz’s work – with eating, which was central to Palekas’s work. The artists collected old furniture and wood from locals in Vilnius through online marketplaces and composed a site-specific installation that mirrored the nostalgia and scarcity prevalent in former Soviet countries. Throughout the programme, we activated this installation by holding workshops and a final dinner in the scenography, which served as a multi-sensory amplification of our theoretical reflections.

SR: In her book Trauma and Recovery (2015), Judith Herman emphasises the significance of narrative and community in healing from traumatic experiences. Are there any childhood stories or myths that you feel comfortable sharing?

MGD: During a time of scarcity and hardship, my German grandmother crafted medicine from plants found in nearby fields and forests. She drew inspiration from Hildegard von Bingen – a German Benedictine abbess, composer, philosopher, mystic, and medical writer from the High Middle Ages – who hailed from the same region as my grandmother. While Bingen is often seen as a New Age icon today, to my grandmother she embodied a Spinoza-esque belief in the interconnectedness of all things, recognising that plants possessed agency and power beyond human understanding.

The scarcity my German family faced was partly due to my grandfather’s refusal to join the Nazi Youth. This decision barred him from further schooling, leading him to become a farmer despite his keen intellect. Though mythology played little role in my German family’s life, there was a palpable reliance on the fields, forests, and myriad non-human entities that surrounded us.

On the Slavic side of my family, the pagan beliefs that survived Christianisation regarded organic elements, such as wood and water, as essential in the process of grief and loss. For instance, placing cemeteries near rivers or lakes was (and in some places still is) believed to create a natural barrier for souls that might trouble the living. In cases of “bad deaths,” such as those occurring during wars, it was believed that these sites needed to be memorialised.

Shortly before my aunt’s sudden passing in 2024, I intuitively asked her once more to record the story of my Polish grandmother, who was born in the village of Buczacz, now in Western Ukraine. My aunt described how the attacks and slaughters in the village during World War II resulted in the “river Strypa turning red.” This depiction makes me wonder how rivers and other natural entities might serve both as agents in the removal of evidence and as guides for troubled spirits of the dead, leading them away from the living.

SR: I’m interested to know more about your latest projects about trauma, memory, and family history. How does your research practice explore the impact of both personal and collective traumatic experiences on memory and our connections to our ancestors? Additionally, how does this relate to your perspective on the relationships between different species?

MGD: I officially began my PhD fellowship in the Bi-National-Programme between HfK Bremen and Gothenburg University, under the primary supervision of Prof. Dr. Mona Schieren in 2024. Over the next few years I’ll be working on various artistic projects – not merely as artistic presentations but also to produce a form of practice-based theory. This theory will reflect on World War II experiences from a working-class, agricultural, queer-feminist, and post-migrant background.

My current research projects aim to move beyond an auto-ethnographic approach, merging it with my ongoing research on interspecies reflection. A key component of this research is the field study of two former World War II sites: one in the Eifel region of West Germany, and another in Buczacz, near the Strypa River in Western Ukraine. These locations are not only post-war and present-war landscapes but also the birthplaces of my German grandparents and Polish grandmother. Rather than viewing these places solely as auto-ethnographic sites, I intend to treat them as memory archives that can be activated or transformed through rural rituals. By aligning human trauma experiences with more-than-human perspectives, I hope to propose reparation models that involve other-than-human viewpoints. In this process I aim to further decentralise the human by pluralising the “singular” entity in trauma studies, as suggested by decolonial researchers. A central question that has emerged over the years is whether we can access earthly landscapes as memory archives when contemporary witnesses are gone and when documentation has been looted or destroyed as part of genocidal war strategies.

Almost eight decades after World War II, the 20th century’s atrocities continue to affect survivors’ descendants and non- and more-than-human entities, resulting in a non-linear perception of time. As artist Shira Wachsmann eloquently puts it: “The effect of trauma is the opposite of linear time. The past is projected into the future coming back to create the present, creating a fluid environment that allows the living trauma to take shape and circulate.”

Growing up in a post-war site, I witnessed war memories and remnants interrupting daily life’s randomness – a constant eerie silence against an undefinable backdrop of noise. Finding grenades in our Eifel garden while planting vegetables, or my grandfather regularly encountering bomb shrapnel when cutting trees in his forest, were common occurrences that transcended time and space. Drawing on feminist theorist and physicist Karen Barad’s concept of “Hauntological Relations of Inheritance,” I aim to connect the “dis/orienting experience of the dis/jointedness of time and space, entanglements of here and there, now and then” to these phenomena. Encounters with the apparent past, such as finding a grenade in our garden, exemplified the material, and haunting, continuity of seemingly concluded events, transforming the present into an infinite archive. I argue that a lack of thorough and interspecies analysis of World War II events – which have become subject to instrumentalization rather than proper processing and mourning – continues to impact our present day and perpetuate violence.

Referring to Michel Foucault’s “history of the present,” I believe we need to approach history and its theorisation like an archaeological field, harvesting ideas from it for our present situations. In this context, I think that only by acknowledging the paradoxes and complexities of internationally intertwined histories – and accepting that there is a multiplicity of narratives, many of which claim to be the singular reality – can we start speaking about the past and its ongoing impact on the present. When examining the post-war years, we observe that the focus was on overgrowing/rebuilding and an accelerated growth, rather than creating space to process feelings of shame, shock, and a lost sense of humanity. Restoring confidence after enormous atrocities requires more than monetary reparations or economic benefits – it demands rituals that can unite a diverse society. Instead of fostering intersectional solidarity, recent years have witnessed increased polarisation and a destabilised left, while right-wing populists gain more power. This trend echoes Hannah Arendt’s observations in The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951).

SR: How do you see the evolving understanding of landscapes as dynamic entities and the role of non-human agencies reshaping our perception of memory and trauma, influencing the research you are pursuing in your new project?

MGD: As survivors remain silent and archives are erased, landscapes have become crucial in the search for answers – but this also raises new questions. The integration of the “implicated” landscape, or “traumascape,” is, as multidirectional memory scholar Michael Rothberg states, “complex, multifaceted, and sometimes contradictory, but […] nonetheless essential to confront in pursuit of justice” (2019). “Bystander art” has emerged as a new form of artistic practice in recent years, appearing in various exhibitions and conferences throughout this year. Anthropologists Aleksandra Janus and Roma Sendyka, who work at the intersection of art, science, and activism, explore this concept in their 2021 paper “Depth of the field.” They note: “In the last decade the term landscape has become a conceptual basis for many, ever more specialist and precise terms in studies on memory. […] Accenting the aesthetic attributes of a landscape surrounding a non-site of violence sharpens the contrast between the associations evoked by what is seen and those evoked by what is known. […] Lupine and pine trees grow on the ashes of the victims of Operation Reinhardt […]. Nature hides the crime in an act of cooperation with perpetrators and beneficiaries.”[5]

I wonder: What do we actually envision when we think of the word landscape? Common conceptions include fields, forests, or romantic Caspar David Friedrich paintings, but aren’t plant, animal, and human bodies landscapes too – merging with other landscapes, which are themselves composed of multitudes? Symptoms of intergenerational trauma are typically addressed as human experiences, yet they are inherently bound to a vast network of agencies and landscapes. Or, in the familiar Latourian terms: We are interconnected as equal actors with other people, objects, organisms, and environments.

As peasants and foresters, my agricultural family was tied to their environment, actively experiencing the symptoms of solastalgia – a term defined by philosopher Glenn Albrecht as “the condition of existential distress caused by the physical destruction of one’s immediate environment.” These inseparable and porous connections between human and more-than-human agencies demonstrate how an entity is always bound to the chaos of its environment. As chemist and philosopher Isabelle Stengers and Nobel Laureate Ilya Prigogine explained in their multi-layered work Order Out of Chaos (1984), “Whatever we call reality, it is revealed to us only through the active construction in which we participate.”

SR: In projects such as The Aesthetics of Knowledge (2019–ongoing), you consider working with more-than-human agencies as a form of collaboration. How do your sculptural works intertwine with your practice-based research projects on intergenerational trauma?

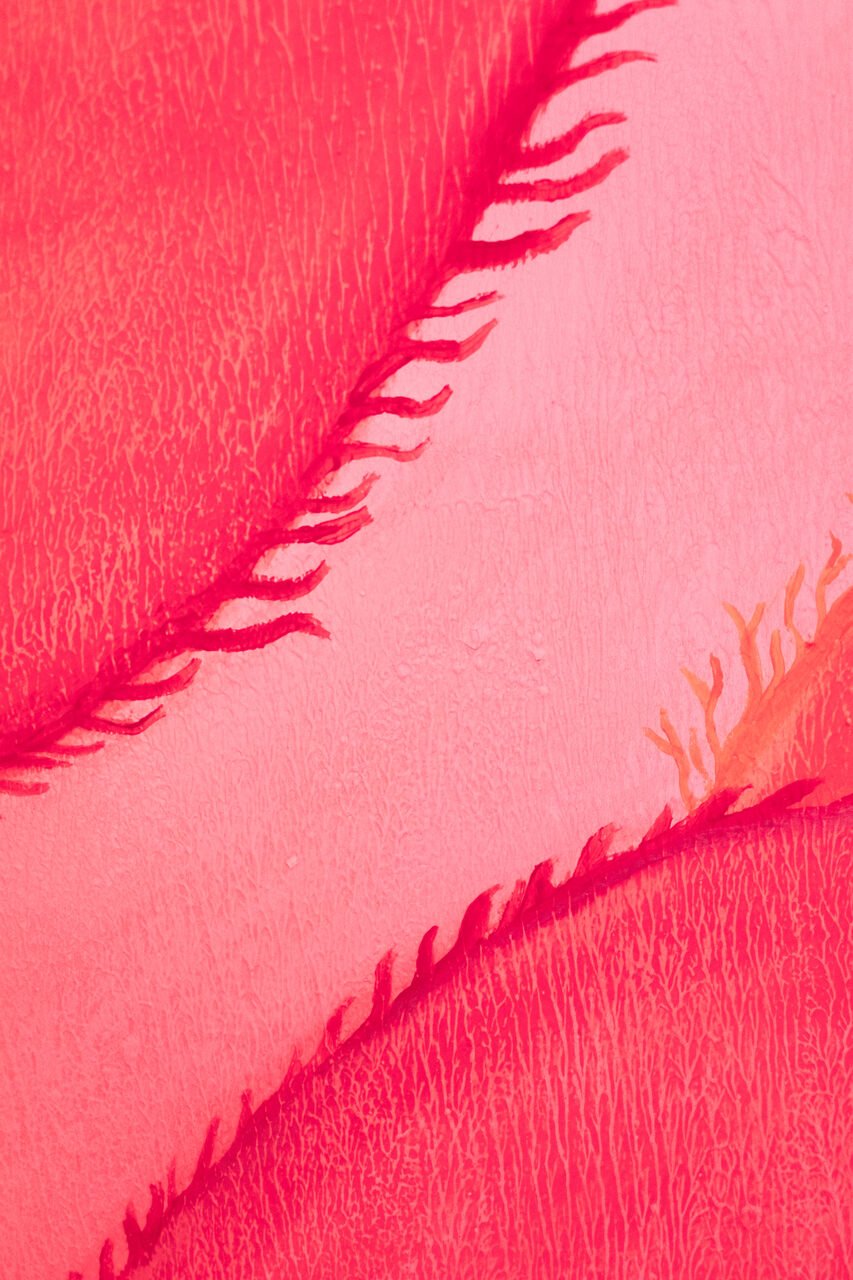

MGD: In addition to workshop and seminar formats, I create sculptures using growing stones as active agents and compose text and sound-based scores that explore my research into trauma and alienation. In 2019, I initiated my series Aesthetics of Knowledge, which I consider as an co-authored composition with the stones and materials that are integral to it. As an avid stone collector, I received a stone from friends that was believed to possess the ability to grow into a crystal. Over the years, I have experimented with this and similar materials, adding new pigments and both organic and inorganic fluids. This composition has become one of my preferred artistic mediums and has been integrated into numerous sculptures and site-specific installations. Often, I construct a framework for the growth process that includes the agents of crystallisation, allowing the crystal’s natural properties to determine the outcome of the work. This unpredictability has posed challenges for some curators, as the liquid does not conform to certain human parameters and aesthetic guidelines. I believe that this de-centered approach aligns with my focus on solastalgia from 2015 to 2017, which explores the interconnected relationship between the changing environment and the human psyche. As humans, we do not merely shape the environment; rather, the environment shapes us.

By connecting human trauma experiences with more-than-human perspectives, I aim to propose reparation models that incorporate non-human viewpoints, and allow to expand the limited scope that the term trauma typically encompasses. This approach seeks to decentralise the human in trauma studies by pluralising the concept of a singular entity. A key question that has emerged over the years is whether we can access earthly landscapes as memory archives – especially when contemporary witnesses are gone and when documentation has been looted or destroyed as part of genocidal war tactics. My artistic works aim to determine how the dualistic separation of humans and the environment impacts the treatment of war-related trauma. I critically reflect on the need for parallel treatment of human, other-than-human, and more-than-human entities as porous, plural, and interconnected beings. This approach serves as a means for genuine reparation while also considering the landscape as a witness.

Hierarchical divisions between human and non-human entities became entrenched in Western scientific contexts. As scholar and feminist activist Silvia Federici illustrates in Caliban and the Witch, these divisions intensified with the rise of capitalism in 17th-century Europe. Authorities used witch burning as a tool of terror to divide and subjugate communities, punishing those who maintained hybrid companionships with their non-human kin. The exploitation and destruction of land and people for privatisation continues today in the form of extractivism. This term, as Uruguayan biologist Eduardo Gudynas wrote in 2015, originates in the Spanish-speaking Latin American context, particularly in relation to natural resources and Indigenous Peoples’ resistance.

SR: Your almost predisposition towards an empathetic connection with non-human agencies is very intriguing to me. I have the impression that the beliefs belonging to your family regarding entities like the river or the wood may have led you to (re)connect with them through your artistic practice. In How Forests Think (2013), Eduardo Kohn challenges the very foundations of anthropology, questioning the basic assumptions of what it means to be human. If we shift our anthropological observation to examine how humans relate to other living beings, the traditional Western perspective begins to collapse.

Now, let’s imagine being one of the stones you use as material for your art and research. Embedded within that stone, or other more-than-human agencies, such as trees that sway gently in the breeze, rivers carving their paths through the landscape, or the mycelium networks hidden beneath the soil, you would perceive the world around you in a new way. How would you perceive yourself, then, existing within those forms?

MGD: In 1974, philosopher Thomas Nagel asked in his paper of the same name, “what is it like to be a bat?”, and suggests that an animal’s experience is inaccessible, so we can’t truly know what it’s like to be a bat. This idea makes me think about how humans have learned to see themselves as separate from non-human nature. To really connect with nature, we might need to look at how people who work closely with animals and the environment live. Farmers, for example, develop a special relationship with animals, trees, and even stones through their daily work. By constantly interacting with nature, they become deeply connected to it, forming what scientist Donna Haraway calls “odd-kin” or unusual family-like bonds.

In Deborah Stratman’s film Last Things, she delivers an astonishing portrait of stones, which apparently don’t have memories like we do. But I think that when humans and nature interact closely, we can somehow express memories or experiences for non-human things. It’s like when you spend time with a pet and start to understand its needs and feelings; I would claim that one does not just imagine human feelings in nature. Instead, it’s a real exchange between living things and their surroundings. Perhaps we can apply the theory of mirror neurons here, which helps us understand others’ actions and feelings. For example, my grandfather, who worked in a forest all his life, literally carried that forest inside him. He understood it deeply. In this kind of relationship with our environment, we might learn from trees or stones how to let go of painful memories. And at the same time, with the ongoingness of ecocides and genocides, the evaluation and recognition of past and ongoing human trauma, continues to be a relevant embodied evidence of violence and tool for intersectional resistance.

Monika Gabriela Dorniak is a German-Polish artist and researcher with an interdisciplinary background in fine arts, choreography, psychology, and design. She often merges media – specifically performance, (textile) sculpture, and multimedia. In her practice-based research, Dorniak explores the structures of the Self through a multifaceted analysis of body, mind, and environment, considering the regressive history of nature’s domination and social power structures. Her auto-ethnographic research on intergenerational trauma, migration, and belonging is advanced through ongoing collaborations as part of socially engaged commissions, including Counterpoints Arts in London (2021–2022). Dorniak has presented her works at international institutions such as Kesselhaus at Kindl Berlin (48 Stunden Neukölln, 2024), Nationalgalerie Vilnius (2023), Drugo Mare in Rijeka (2022), Uferstudios Berlin (2021), Kommunale Galerie Bärenzwinger in Berlin (2019), Tate Exchange at Tate Modern London (2017 & 2018), Arts Catalyst in London (2016), and Foreign Affairs Festival at Berliner Festspiele (2014). She has also been a guest lecturer at SOAS University of London (2022), Garage Museum in Moscow (2019), Al-Quds Bard College in Palestine (2018), and Chelsea College in London (2017). Dorniak holds a Master’s Degree in Art and Science (Department of Fine Art) from Central Saint Martins in London (2017). Since 2024, she has been a Ph.D. candidate in the art- and science-based Ph.D. program between HfK Bremen and HDK Valand in Gothenburg.

Silvia Russo is a Berlin-based art curator, originally hailing from Sicily. Her academic background encompasses both Psychology, with a final thesis research in the field of Neuroaesthetics at the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, and Curatorial Studies, through a path between the NODE Center Institute (2022/2023) and IED Institute of Florence (Master’s Degree in Curatorial Practice 2023/2024), culminating in a final project (exhibition, workshops, public program and publication) in collaboration with Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, from October to December 2024, exploring the meaning and significance of the concept of “community” in the contemporary discourse. As a multidisciplinary curator, fascinated by the intricacies of the human experience, Silvia delves into the inner workings of the artistic mind, individual narratives, and emotional as well as cognitive landscapes that deeply shape us. Raised with Mediterranean values fostering strong connections and care for both self and community, her curatorial practice strongly emphasises the individual and the broader spectrum of self-experiences, and, by extension, the dynamics of society. She believes that is essential, in the contemporary age, to promote an interaction between the intimate dimension and the social fabric, in order to dismantle the barriers of alienation and isolation typical of the post-modern era, allowing the personal experience to reverberate in the collective one. Through an organic, convivial and participatory taking-care approach, she seeks to facilitate dialogues to create empathetic intersections between stories and people, places and narratives, and among individuals themselves.

[1] “Seduta Artistica” is a project curated by Silvia Russo, dedicated to the free emotional and creative expression of artists, with a focus on their personal narratives and self-development within the dynamics and challenges of contemporary contexts and discourses. Through an honest and open dialogue, the project focuses on building a curatorial relationship based on attentive and profound listening. During the interview, the curator adopts a non-invasive approach, allowing the artist’s flow of thoughts to develop freely, without interference. The project aims to give voice to the more intimate and lesser-known side of the artist, often hidden from the public eye. Seduta Artistica thus presents itself as a space for inner and authentic exploration, beyond conventions and external expectations.

[2] Laban’s principles, developed by Rudolf Laban in the early 20th century, form a comprehensive framework for analyzing and understanding human movement, known as Laban Movement Analysis (LMA), which comprises four main categories: Body, Effort, Shape, and Space (BESS).

[3] Invited practitioners who contributed to the first seminar: Olesya Khromeychuk, Nina Mdivani, Jäckie Rydz, Jessica Ostrowicz, and Red Zenith Collective. Invited practitioners who contributed to the second seminar: Jessica P. Cerdeña, Tiara Roxanne, Svitlana Biedarieva, Eliana Sola Bussas.

https://counterpointsarts.org.uk/event/uprootedness-hybridity/

[4] Full list of artists and scientists who participated in the programme Passing on Resilience: Kamal Ahamada, Rasa Antanavičiūtė & Austėja Tavoraitė, Ieva Balčiūnė, Liza Baliasnaja & Rūta Junevičiūtė, Danutė Gailienė, Katherina Gorodynska, Agnė Jokšė, Michal Jurgielewicz and Jonas Palekas.

[5] Janus A, Sendyka R (2021) Depth of the field. Bystanders’ art, forensic art practice and non-sites of memory. International Journal of Heritage, Memory and Conflict 1: 73-83. https://doi.org/10.3897/hmc.1.63264