Yuliia Elyas

The ongoing russian invasion of Ukraine has led to nearly 14 million Ukrainians being displaced – some still within the country’s borders, while many have sought safety abroad. Artist Anna Kakhiani used to live and work in Kyiv. Since the full-scale invasion she is now based in Amsterdam. In her recent exhibition, Hug Me with Words, or Maybe Not, at WG Kunst, she navigates her experience of forced displacement.

In the exhibition, words and emotions materialise into tangible objects that occupy physical space. These objects represent the barriers between, facilitating dialogue and reflection, perhaps even a sense of closure. Kakhiani’s works present observations, collaborations, and overheard conversations, shedding light on the emotions and societal pressures that displaced people face. Her material research explores how language falls short in conveying a sense of belonging, reflecting not only external patterns but also her own personal limitations.

I visited the exhibition Hug Me with Words, or Maybe Not on its opening day. Since 2023, Ukraine has been designated as one of 21 focal countries in Dutch cultural policy, which has resulted in increased resources for cultural cooperation between the Netherlands and Ukraine. As a consequence, the Dutch Foundation for Literature and the Support Fund for Ukrainian Makers has received additional funding from the government to support artists who fled russian aggression after February 24, 2022 and are currently residing in the Netherlands. Kakhiani received support for this exhibition through this program, working with VATAHA, an organization based in Rotterdam that is run by the Ukrainian diaspora. VATAHA plays a crucial role in supporting Ukrainian artists, humanitarian initiatives, and strengthening international communities.

The exhibition begins with a booth containing a listening device and a text that reads, “This is the space where you can listen to the thoughts and feelings shared by a stranger, as well as share anything yourself by recording your audio message.” After recording mine, I realised I had overwritten a message left by the person before me. Because the audience has access to the other recordings, the act of sharing can also lead to the potential loss of messages of others, which created in me a profound sense of urgency for how fleeting communication can be. It also emphasized the experience of occupying space with one’s presence. Many attendees engaged in this group experience.

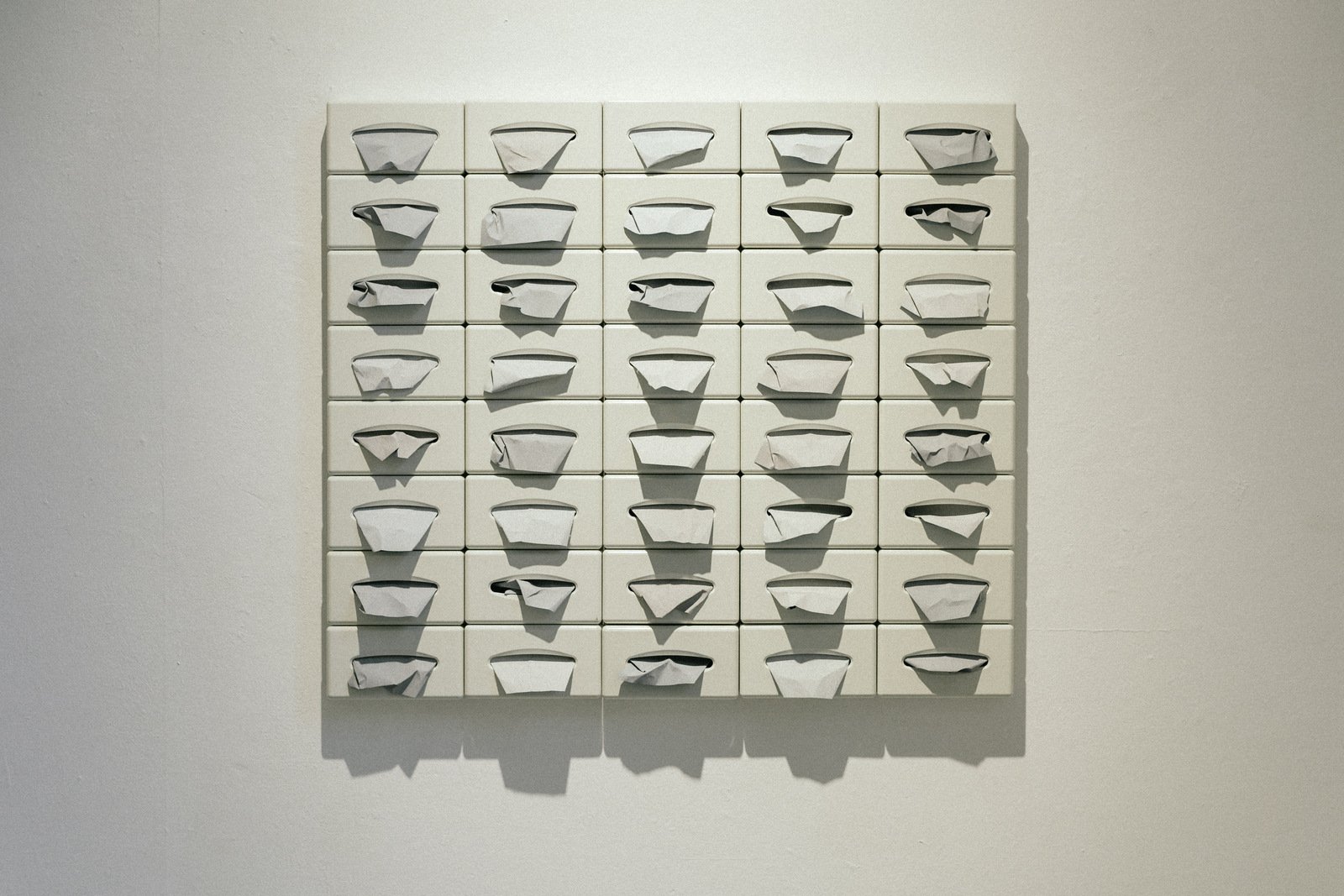

The exhibition continues with a collaborative piece with artist Yasya Xomenko titled Keep Smiling, showcasing heat-printed T-shirt designs. The installation presents multiple T-shirts embellished with smiley face prints, displayed hanging from an ironing board, with one T-shirt hanging separately from a metal hook from the wall. Although the shirts display cheerful smiley faces, they are applied with heat onto the folded fabric, which creates a sense of distortion and awkwardness. These T-shirts are then available for purchase as exhibition merchandise. As described by Xomenko, this imagery reflects a “reactive mask” that hides genuine emotions, resonating with themes of social restraint and the denial of traumatic realities.

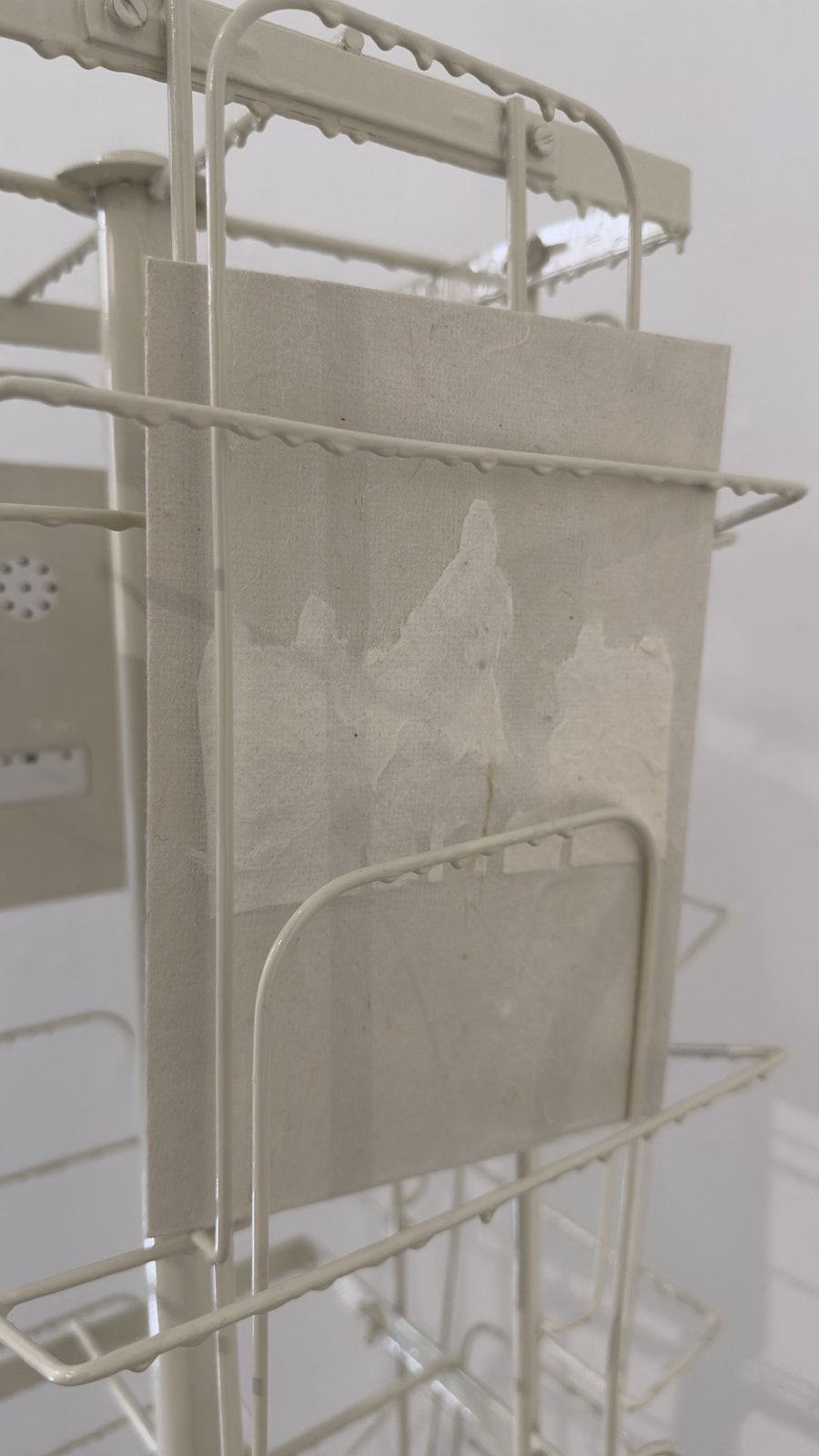

One of the most impactful pieces is Linguistic Hospitality, where Kakhiani explores the idea of “shibboleths” – words that serve as linguistic markers of identity. This work uses a rotating postcard stand as its physical structure, displaying two types of music postcards. One card reads “palianytsia” and the other “Scheveningen” – both words historically used as linguistic tests to distinguish between locals and outsiders. The Ukrainian word “palianytsia”, a type of bread, is notoriously difficult for russians to pronounce, while the Dutch “Scheveningen,” the name of a sea-side district of The Hague, served as a password during World War II to identify German infiltrators. Connecting history to the present, his installation underscores how deeply entrenched such linguistic practices remain.

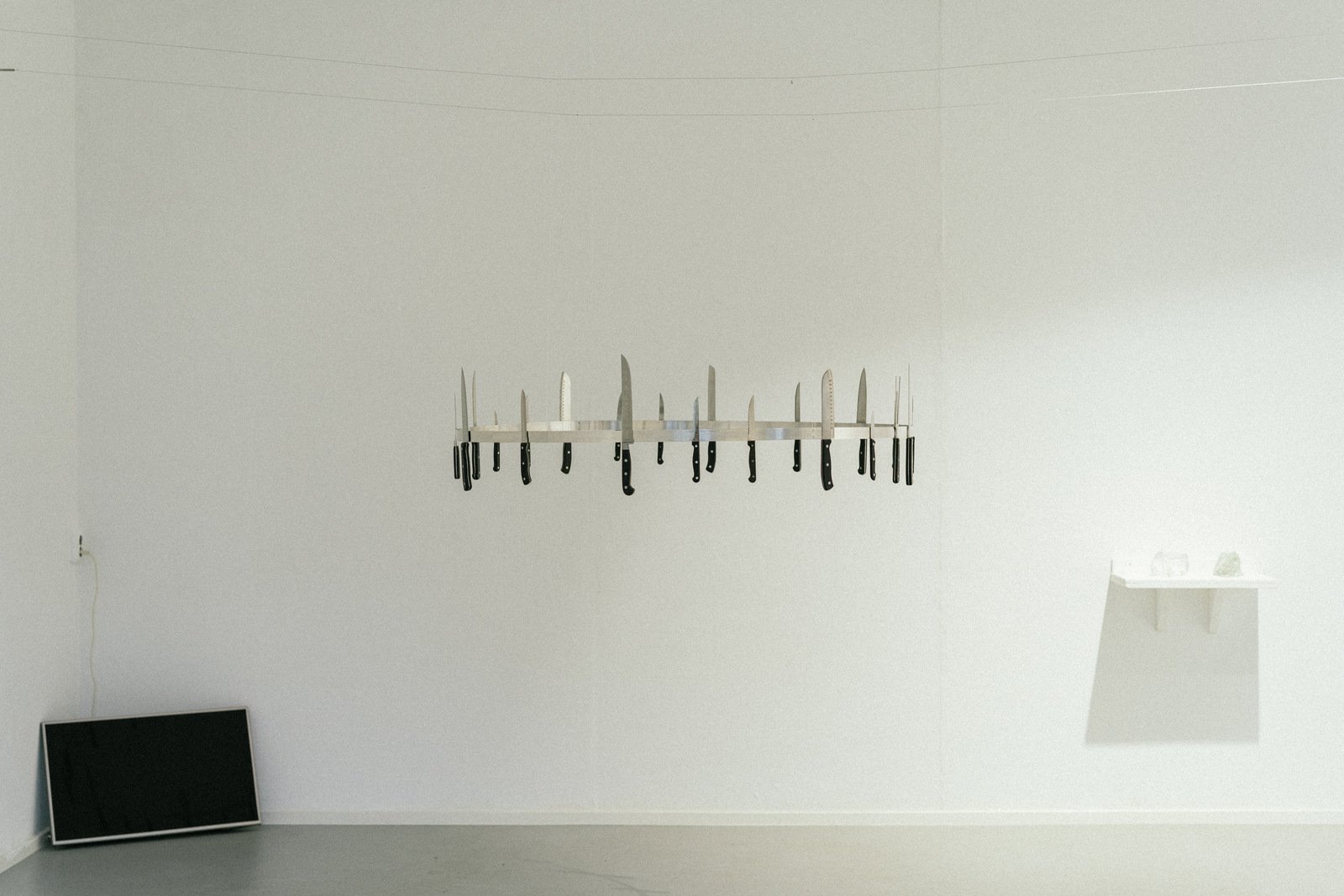

Without a doubt the most discussions centered around the piece titled Kitchen Conversations. The installation included 21 kitchen knives, engraved with the often hostile or alienating phrases that refugees encounter, phrases that cut deep into their sense of belonging. Kakhiani conducted research, collecting the experiences from the Ukrainian diaspora in the Netherlands. Among them were notes like “Is your property still intact?”, “Where do you see yourself in 5 years?”, “it is the putin’s war”, “But there is no fights in your city” or “War opened so many opportunities to you abroad”.

Kahkiani used examples from her own personal experience, confronting viewers with the insidious repetition of words that seem harmless on the surface but which are loaded with ignorance. But those phrases served as great conversation starters among the visitors of the exhibition. I witnessed people sharing their experiences, adding to the list of existing phrases. The engraved phrases become signifiers of perhaps what is projected onto the forcibly relocated communities. These are not authentic expressions of solidarity but responses that reveal more about the speakers’ own discomfort than a genuine desire to support or empathize. In trying to ease their own unease, people often resort to clichés, which can feel empty or even alienating to someone who has experienced trauma firsthand.

Happiness Pills features a cake made entirely of paracetamol and playfully critiques the way empathy becomes numbed. In the Netherlands, it’s almost a running joke that your doctor’s solution for everything is “just take paracetamol.” Kakhiani taps into this, poking at how society reaches for quick fixes to mask pain and discomfort, often at the expense of real emotional connection. She also references scientific research that confirms paracetamol usage decreases empathy.

To close the exhibition, a panel discussion was held on July 21, featuring guest speakers who explored the theme of empathy and the connections between those living in safe distance from war and those directly engaged with it. The panel included Dutch visual artist and curator Christian Van Der Kooy, known for his long-term photographic projects on identity, particularly in Ukraine; Annosh Urbanke, an independent curator and researcher with a focus on post-socialism and neo-avant-garde movements in ex-Yugoslavia; Maarten Dekker, who has experience in psychosocial support for Ukrainians; and Daria Delawar-Kasmai, a member of Empatia Program, who shared her personal experiences as a displaced Ukrainian and her work in mental health support for refugees in the Netherlands. I appreciated the variety of panelists, as they attracted a wider audience beyond the conventional contemporary art enthusiast, and reached new communities, not just those already familiar with Ukrainian issues.The conversation touched on the idea that empathy might sometimes mean embracing not knowing rather than imposing predefined responses. The expectations imposed on Ukrainian refugees – to behave or express gratitude in specific ways – reveals a kind of patronizing empathy that lacks genuine understanding. The tone of the conversation seemed to have been one of thoughtful introspection, with participants willing to delve into the challenging emotions and uncertainties that come with offering support to refugees. The participants’ openness to “sit with complexity” was truly valuable. I wish these conversations could become a regular series of events, giving us an opportunity to invite more guests from diverse backgrounds. Dutch culture, in particular, holds a strong belief that nearly any issue can be resolved through dialogue.

An interesting moment during the panel came when Delawar-Kasmai shared a story that related to the engraved kitchen knives. She was invited to an interview and was asked if she could ever forgive russians. She felt irritated by the question and found it very inappropriate, but responded calmly, pointing out that no one had ever actually asked her for forgiveness. Her words moved the audience to tears, though she herself remained composed.

It’s important to avoid generalizing Ukrainian society as a homogeneous group, as there are diverse perspectives and experiences within it, as with every group or community. Emotions are part of the human experience and can offer valuable insights into empathy and connection, but they are not always light or happy. The panel addressed this, how empathy can sometimes be selective, and that the ability to empathize is often a privilege in itself. Empathy requires emotional energy, mental space, and a certain level of security – conditions that are not equally accessible.

Kakhiani’s work exposes the gaps between words and actions, empathy and indifference, employing the very language used in these situations as their own critical system. Her work compels the viewer to confront their own assumptions, questioning how much they are truly willing to embrace or how much discomfort they are willing to sit in to understand another. Kakhiani embraces this, and uses observed words and feelings as a powerful starting point for dialogue. It’s an unapologetic exploration of a territory long deemed taboo, creating space for complex conversations that are both personal and political.

Artist: Anna Kahiani

Exhibition Title: Hug Me with Words, or Maybe Not

Venue: WG Kunst

Place (Country/Location): Amsterdam, Netherlands

Dates: 13.07 – 21.07.2024

Photos by: Hanna Hrabarska, Anna Kakhiani, Alina Kozakova, Lera Manzovitova, Anastasia Prokofieva