Weronika Zalewska

Envisioning resistance through daily practices of tending the land, worker movements, as well as artistic-discursive reflections – not as separate but co-dependant and complementary regenerative strategies – is an exercise in which many well-defined boundaries can blur. Lined with evaluative divisions between physical and mental labor, and the tensions between rural and urban, local and global contexts, today’s political landscape most often fails to hold the complexities of human and more-than-human ecologies, or reflect upon means of production, following the “divide and rule” in always seemingly-new colors. We’re living in times when the urbanized left has drifted away from worker movements and when ecology often remains stripped down to a legislative battleground rather than embodied collective security and nourishment.

The 3rd edition of Biennale Matter of Art tends to this complexity as if it was a translocal philosophy class and a practice of regenerative farming at once. And I do see these two not as contradictions, but as pieces of the same puzzle of some of the more interesting challenges of today (and every day). Letting the soil show the way, Matter of Art attempts to embrace complexity, and shatter the notions or ideas that mistake diverse commoning practices for the brainchildren of communism in the context of Central Eastern Europe and Central Asian totalitarian trauma. And it does so not so much by looking up, as by digging into the matter of (post)artistic practices, giving much weight to acts of listening as spaces of education. But is it enough though to break bubbles and create actual allyships, which we too often dream of from behind the sealed-off walls of galleries?

Biennale Matter of Art, organized by tranzit.cz, was founded in 2020 with the intention to hold large-scale exhibition projects that would develop diverse institutional, political, and communal interventions.[1] Focusing on the notion of solidarity and resilience – however popular as exhibition titles and coverstories – the biennale does emphasize the importance of peripheral visions and the merging of theory-practice, taking art off the pedestal in the white cube and bringing it into the broader scope of activist communities. Curated by Katalin Erdődi and Aleksei Borisionok, this edition of the biennale sprouted not only in the halls of the main venue at the National Gallery Prague – Trade Fair Palace and Lidice Gallery, but also in locations as diverse as the permaculture farm Jednorožec or V.kolona cafe located in the Bohnice Psychiatric Hospital. The accompanying public and educational programs were not so much obligatory additions to the exhibition as an actual space of fermentation and exchange among and between communities.

The 3rd edition of Biennale Matter of Art kicked off with its opening program on the 13th of June, with the merging of voices that stated – with strength, gentleness, and humor – the event’s attempt to dialogue beyond the urban-rural divide, and emphasized the importance of translocal solidarity in the contexts of land and worker rights (despite what many institutions try to tell us today). This couldn’t have happened without voicing solidarity against the ongoing invasion of Ukraine and genocide of Palestinians, along with the many ecological aspects of colonialism that endure, such as resource looting and the destruction of food security, seed diversity, or land-tending traditions.

These matters merge with stories of power struggles in rural Turkey, Kazakhstan, or Hungary, as well as local Czech contexts, though not without a much needed playfulness of coming together in music, poetry, humor, or various forms of mourning. For the opening program, the Prague-based women’s folklore ensemble Lada Choir, and the Hungarian conceptual music project, Peasants in Atmosphere, came together for the first time, performing songs of solidarity in the fields as well as ballads about the lives of rural women. The duo of Olia Sosnovskaya and Elske Rosenfeld performed Archive of Gestures: Becoming In/visible, sharing strategies of invisibility from the diverse history of protest movements in Eastern Europe and beyond, inspired by “non-movement” (Asef Bayat), “weak resistance” (Ewa Majewska), and “sick woman theory” (Johanna Hedva).[2] Kateryna Aliinyk, presenting her paintings at the main exhibition, was also invited to share her texts in the form of a three-voice performance, telling stories of her family’s and her own experiences in the Luhansk and Donetsk regions of Ukraine, which have been under russian occupation since 2014. She reflected on war and occupation through the lens of nature and agricultural practices, intertwining human and non-human perspectives as well as thinking of and feeling the landscapes she can no longer visit or touch, proposing to resist the violence of war also through the desire to share beauty.[3]

As part of the opening program, stopgenocidevgaze collective brought a centuries-old olive tree into the space of Trade Fair Palace, letting it die gradually over the course of the biennale. The group of artists wanted to draw attention to the ongoing genocide in Gaza and its connection to translocal land struggles, resource looting and inflicted hunger, as well as an appeal to Czech politicians to call for permanent ceasefire. As the collective emphasizes, the decaying tree expressed their increasing frustration with the silence of art institutions and the state of Czech media. Unlike other works, the olive tree was not an official part of the show; it was placed somewhat as a foreign object, representing the rejection of the Palestinian cause in Czech society as “foreign.” An integral part of the intervention was also the very mixed feelings it caused: is it ethical to leave an olive tree to die inside the National Gallery? What does it symbolize, what does it practice?[4]

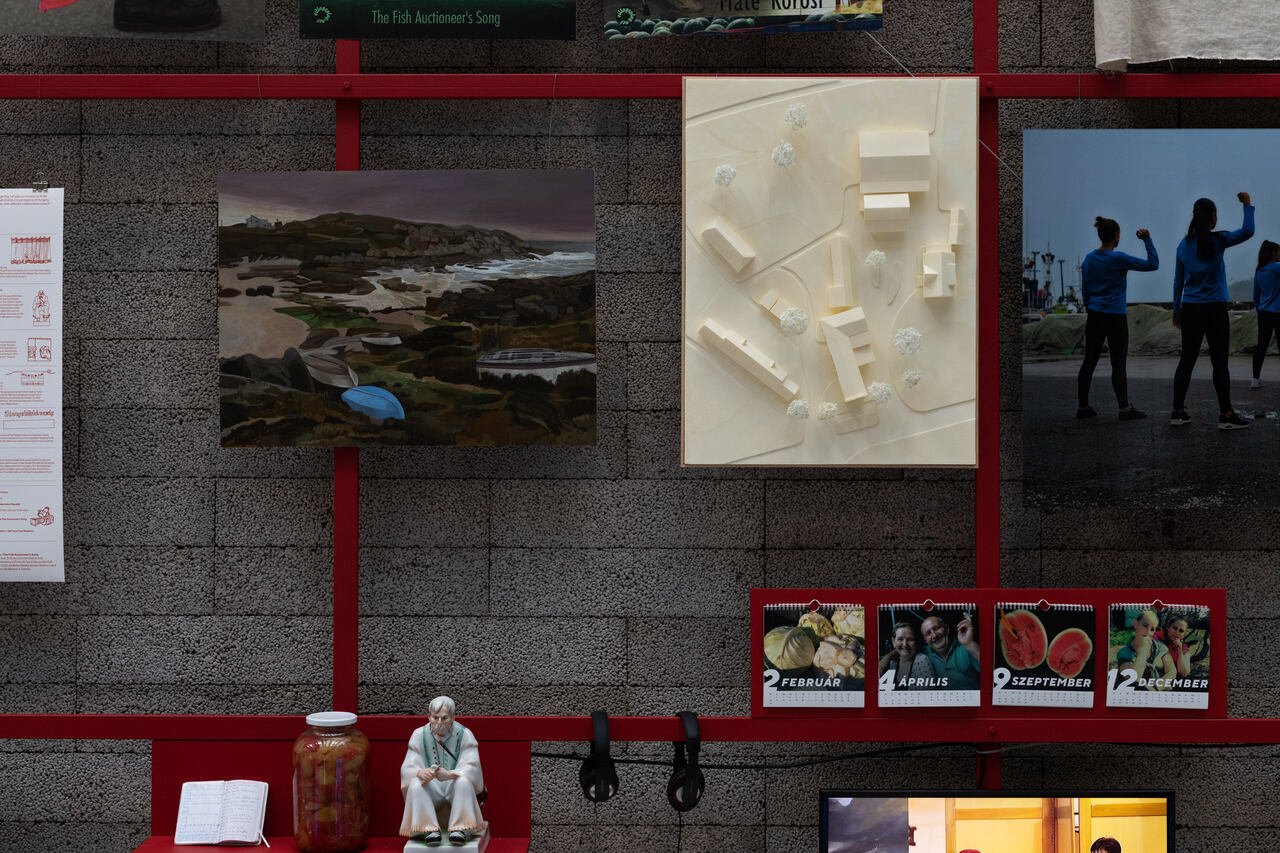

Placed in the vast trade hall, the artworks invited to Matter of Art manifest vivid interactions between each other as well as form their own universes by smell, texture, and the diversely told stories of past-present-futures of worker movements and rural contexts. In the space – which once belonged to the Prague Sample Trade Fairs Association and served as the main venue for trade fairs and a space to exhibit heavy machinery, like agricultural or industrial technology – the turn to rural, communal narratives feels strangely calming and about-right. Carefully curated and neatly placed, not as messy as one would expect with curators relating to the techniques of grafting as inspiration. After the place was nearly destroyed by fire in 1974 and before it became the home for an art institution, there were proposals to convert it into a hospital, a research institute, or a museum of the revolutionary workers’ movement. Andhere we are, in this institution of art, reflecting on questions such as what tools, what knowledge, what traditions do we mobilize in order to resist and undermine domination and oppression?[5]

While posing these questions, we’re still placed in a neat biennale exhibition rather than a workshop ground of diverse worker movements, wandering around and wondering about how messy art can get. Can we turn art institutions into long-term practitioners of cooperative culture, initiators of urban gardening projects or supporters of ecological protests that simultaneously connect people from different social bubbles that one might not be able to merge on their own? Far from a judgemental pledge, I acknowledge that much of this work is already being enacted and often remains invisible – an unspeakable contribution by educators and accessibility teams whose often low-wage labor makes up for “degrowth” and navigates social polarizations, slowly bringing broader groups of (often hesitant) visitors into these grand buildings that many of us have forgotten just how intimidating they can be. Bursting bubbles often happens in small groups and takes time – months and even years. I believe that through its public and educational programs, Matter of Art is kneading that dough. I also believe art institutions won’t serve as long-term navigators in today’s sociopolitical landscape unless we fight for their importance and autonomy, from big exhibition venues to small-town libraries. Culture is underfunded and prone to political shifts all over the place, and it too needs our activism.

These reflections don’t pop-up out of nowhere but are already infused into the different elements of the exhibition. My mind shifts to the metaphor of grafting that the curators of this year’s biennale have chosen to use. Botanical grafting involves the close union of a part of a plant, called a scion, with another plant – a rootstock. When they fuse together, a new organism, agraft, is formed. By connecting the features of different organisms, one can select both resilience and flavor, creating new varieties through experiment. Perhaps our endurance indeed lies in the act of wisely meeting and merging our many skills and knowledges. And, as I’ve mentioned above, we urgently need spaces to continue grafting our mixed varieties of tools, knowledges, and traditions.

One of the pillars of the exhibition were artworks dealing with female agency and feminist approaches to resistance and resilience, from self-organized protests of women in Turkey to the role of (in)visibility and language in demonstrating resistance. Pınar Öğrenci shares Resisting Forest, an empowering video consisting of stories of elderly women from the Black Sea coast of Turkey who protested against the building of a thermal plant in Gerze and a hydro-electric power plant in Aslandere, to protect the more-than-human. These women resisted the police by using their everyday work tools – wooden sticks – to create noise and make their voices heard. Telling the stories of their resistance, they both joke and cry, emphasizing the role of the soil and rivers as places to protect their way of life; cultivate food, rest, and bond. The lightness and grace with which they carry through the harsh experience is owed to their communal support and the joy they find in each other as neighbors, friends and comrades, embodying the strength of grassroots family-making.

This story of resistance comes in dialogue with the work of DAVRA Research Group (Madina Joldybek, Zumrad Mirzalieva, Saodat Ismailova). Taming Women and Waters in Soviet Central Asia is an installation referring to the history of the Great Fergana Canal, a 270 km canal between Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, built in just 45 days in 1939 by 160,000 workers, to bring water from the Syr Darya river to the cotton fields, which produced the “white gold” of the region. Bringing up the contexts of forced labor and ecological extraction during the USSR period, the collective shares stories that are still only vaguely mentioned in Western Europe, where the romanticisation of the USSR project remains prominent while the victims of the regime – both human and nonhuman – remain largely unacknowledged. The canal, the symbol of progress in Soviet-era Central Asia, caused the Aral Sea to almost dry out, bringing out tensions between the neighboring countries due to the lack of water. DAVRA looks for historical connections between the (mis)use of women’s work and water, studying how women danced the “Cotton Dance” (Paxta Raqsi) to motivate the men working on the construction of the canal, blurring the line between leisure and labor.[6] The installation consists of films, photos, textile works, and archival material, as well as cotton pickers’ aprons transformed into embroidery, reflecting upon the relations between water, women, dance, and cotton.

These stories form a circle of unhealed russian imperialism that continues today. In the installation of Kateryna Lysovenko, diverse objects from the Hermitage museum in St. Petersburg face one another – a vessel from Kazakhstan, a figurine from Dagestan, a tool from Ukraine – and tell stories of both colonialism as well as shared, translocal experiences of uprooting and forced migration. I recall the words of Kateryna Aliinyk, “In farming areas, landmines, rocket debris, and human remains exist side by side with crops. This mix reminds us that every battlefield is just a field in the first place. Ukrainians try their best to keep using the land for its original purpose despite everything. But we all worry whether we can eat the harvest. Or have we just lost our appetite? Are the traces on the ground from farming machines or war vehicles?”[7]

The exhibition space exposes us to various expressions of organized and spontaneous resistance within post-socialist contexts and beyond, from gestures of disruption to the dynamics of workers’ movements to the wellbeing of (often invisible) bodies. The included artists share how these gestures could be performed, archived, or activated, though one could also reflect upon appropriation while mostly seeing the name tags of only the artists and not the worker-protagonists of videos or installations; often still credited in groups while artists are named individually. This platforming of those who are typically overlooked was well-expressed in the work The Spectre of Peasantry, a video by Tomáš Uhnák with Tamás Kaszás, Asia Dér, and Asunción Molinos Gordo, which gives voice to the farmers themselves – Adam Čajka, Ramona Duminicioiu (Eco Ruralis, Romania), and Anna Kárníková. Czech farmers’ realities might be different from their colleagues’ in the global South, but they have similar concerns, fighting for their rights to land and for their work to be recognized, both politically and socially.

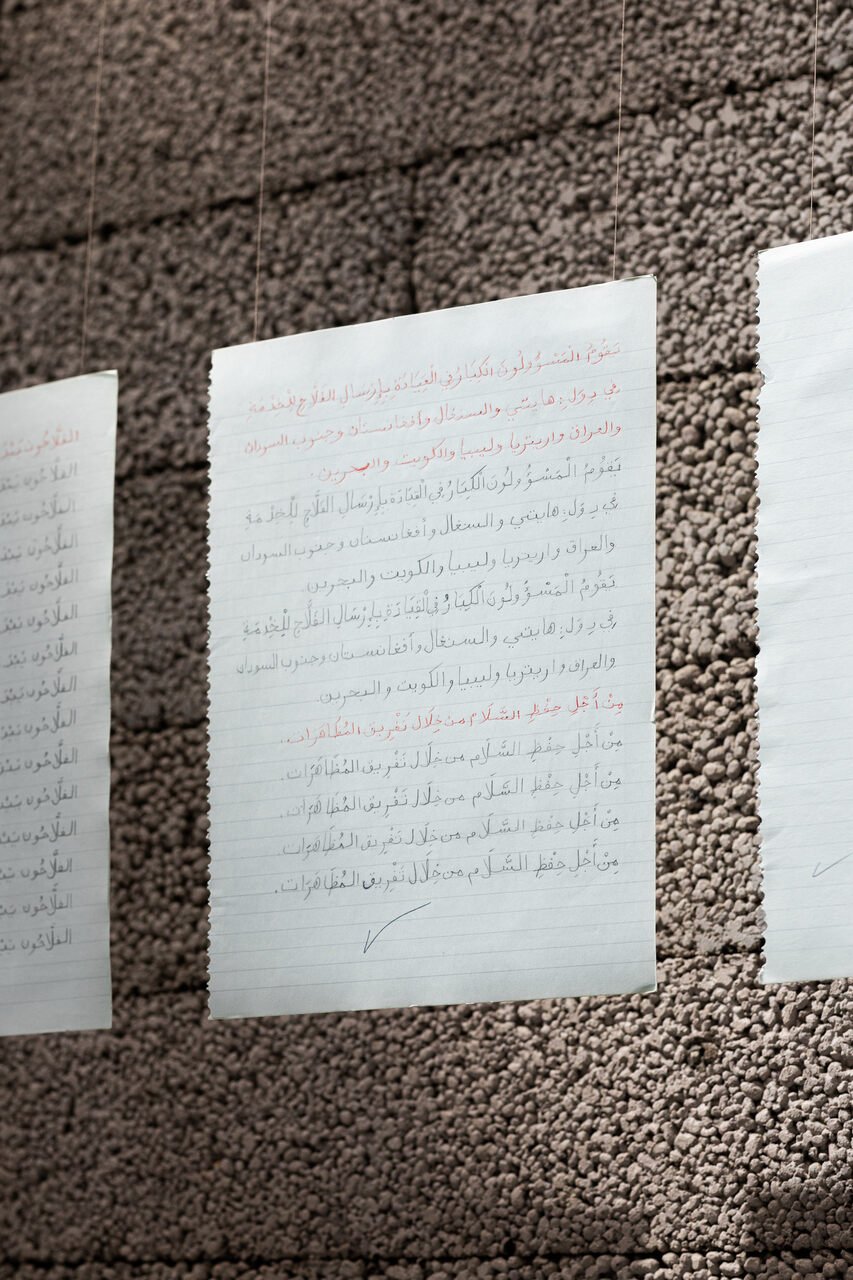

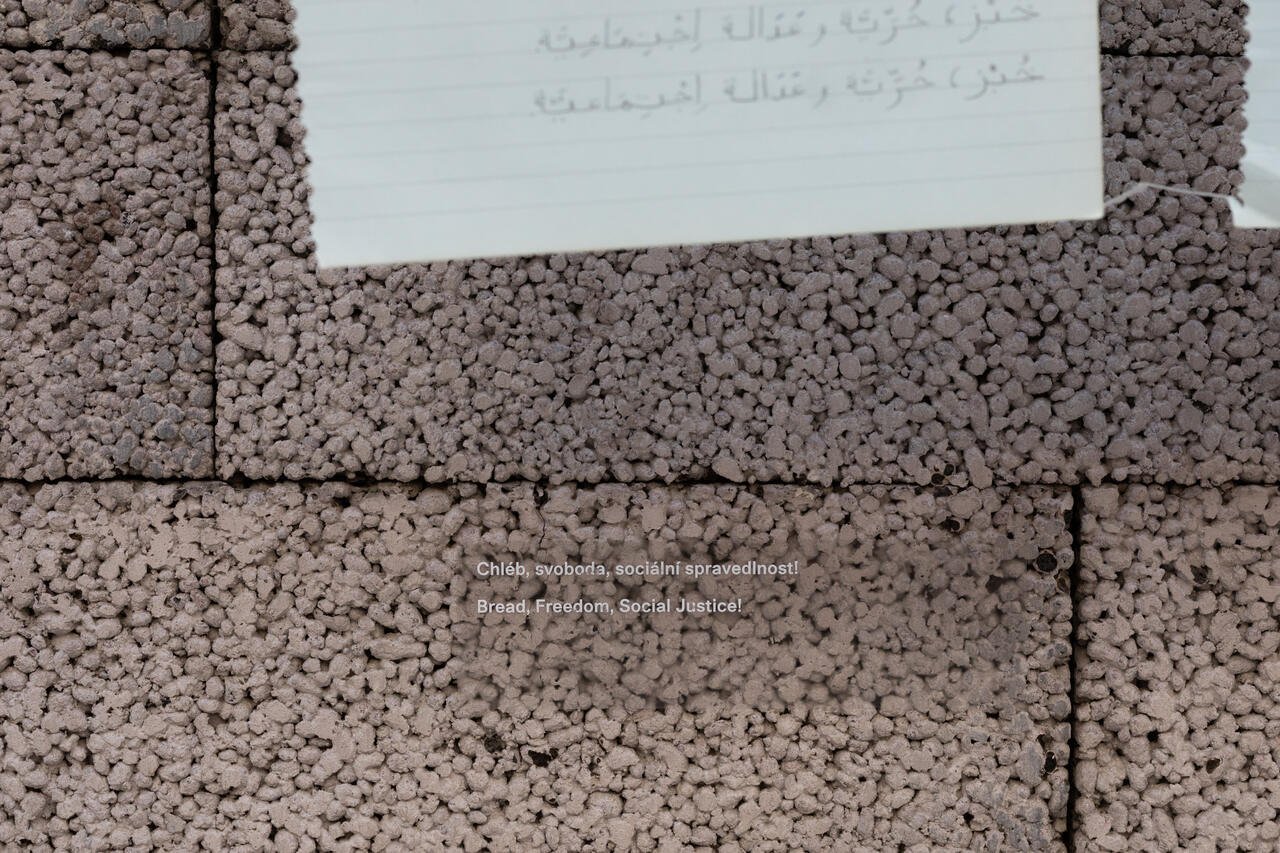

An extremely touching work that relates to rural exploitation and the difficulties of translocal solidarity is El Fellah Ando Fes (The Peasant Has A Hoe) by Asunción Molinos Gordo, consisting of drawings and texts lined up in a row, relating to labor transformation of contemporary peasantry in Jordan. The work is a calligraphy exercise in which we follow the erosion of the labor conditions and land traditions of small farmers. Walking past the installation, page by page, this raw work feels like a profound space of mourning. It follows the spinning wheels of colonialism and capitalism through the universalized parable of one breaking bonds with land and their community by forced migration and exploitative labor, which continues in some distant, dislocated place, with companies often participating in the further systemic depletion of the very communities which had to be abandoned. Depicting the stripping of agency, this personal tale shows the union of land and the human cultures that grow out of it, along with the language, fables, and practices that were born from the urge to nourish the land and its people, many of which today have been consequently abandoned or eroded.

One could also experience the installative documentation of Collaborative Village Play by Antje Schiffers initiated together with Katalin Erdődi, co-curator of Matter of Art. Since 2021 they have worked in different rural regions of Germany, Hungary, and Spain, enacting play scripts with local communities in locations such as a melon stand in an open-air market or a field road with wind turbines as the backdrop. Their collaborators range from farmers, fisherfolk, and hairdressers, to local bands.[8] The village plays are nothing less than experimental and are collectively performed within broad communities, giving space to different opinions and usually inducing large doses of dark humor (which should definitely be acknowledged as resilience practice). To me, the plays show some pretty straight-forward methods of encountering political divisions and taboos in rural communities, which art can (carefully) facilitate. For Matter of Art, Schiffers shared performance props and films that document the collaboration in each place. I would be curious to hear how the resources of the projects were shared among the engaged communities.

Another strong gesture of the biennale, almost a universe of its own, where artistic factors might be less important than the back-story, is the inclusion of Lidice Gallery in the program. Lidice was a village razed by the German army in 1942, with all male inhabitants killed. Its tragedy became a symbol of antifascist solidarity around the globe. After the war, the village was rebuilt for the surviving women and children. The solidarity campaign, Lidice Shall Live, was launched, and involved the creation of a rose garden and an art collection to preserve the memory of the massacre and remind us of the importance of solidarity. The Lidice Collection of Fine Arts hosts hundreds of artworks donated by artists from around the world, from West German artists to artists from socialist and non-aligned countries. To be honest, as a visitor to the gallery, I was not quite sure what curatorial gestures Nikita Kadan has made to a still very classic looking, library-like exhibition, but I highly appreciated the excuse Matter of Art had given me to travel outside Prague to the place where memories of unspeakable violence and translocal solidarity meet, enlivening the thoughts of today’s struggles in Ukraine, Palestine, and of many oppressed peoples, as well as questioning the forms of memory/memorials/monuments of and to ongoing violence. I also experienced the warm hospitality, gentleness, and pride of the local inhabitants working at the gallery, who opened the exhibition for me, as the first visitor that day. In such moments, different worlds mingle more than we might acknowledge when we grab our biennale maps and venture on a trip to a destination location. The contact with such different timescales and communities might as well be part of our common grafting. I’m very thankful for this gesture/effort, for the wounded fields of Lidice give great depth and complexity to the land stories of later worker or ecological movements that are present in the main venue. The women handing me the free ticket might have been the daughters of Lidice victims or survivors, making the short time scale of our own families’ war traumas come back into my consciousness.

During the months of the biennale, the public program extended into a many-legged platform, touching upon the themes of mental health of farmers, organizing a holiday camp for children, or a midsummer celebration at the Unicorn Farm (Farma Jednorožec). As an important public gesture, the Institute of Anxiety invited visitors to the garden at the Psychiatric Hospital in Bohnice. At the one-day event, visitors were invited to plunge their hands into the earth and help the institute take care of flower beds, as “putting hands into the dirt grounds you.” The day continued with the discursive program focused on mental health and burnout among farmers in Eastern and Southern Europe, and was held in the shade of the trees outside the hospital. As the organizers emphasized, those exposed to stress, economic instability, and the effects of climate change should be at the foreground today, which includes farmers in particular, as they are set to experience much more destruction due to the climate crisis. There is very little public conversation about the mental wellbeing of farmers – especially small-scale farmers – whose profession exposes them to high levels of anxiety, burnout, and depression. Market pressures, speculation, and low feed-in tariffs, debt, sales insecurity, loneliness, gender inequalities, and climate change – all this and much more crushes those on whom we depend for the survival of societies and ecosystems all around the world. This event also zoomed in on the political economy of health – the ways in which bodies grow sick and exhausted under the contemporary conditions of capitalism. What is the political context that enables exorbitantly expensive treatments, medications, and therapies, and why is health becoming a commodity? As many health and crip activists demand full access to health, we wonder how ill health can become a common ground from which to struggle against exploitation. How can someone unhealthy and exhausted organize, strike, and resist?[9]

Another day program was the midsummer celebration at Farma Jednorožec. The program started with a guided tour of the farm, followed by Unbreeding Memory, an immersive performance by Kateřina Konvalinová and Lucie Rosenfeldová, who invited participants to explore the history of human–animal relations with a focus on sheep breeding and domestication. Members of Farma Jednorožec led work brigades where everyone had a chance to get their hands dirty while weeding, harvesting, and taking care of the animals at the farm. There was a plein-air painting workshop for adults and kids, a plant worksheet game, and a songwriting workshop, followed by an open conversation on art and agriculture, attended by invited artists, collaborators, visitors, and farmers, around a midsummer bonfire. In addition to the site-specific venues and projects, the biennale designed a diverse program for children which is also worthy of mention. Many workshops were aimed at connecting them to food production and rural practices, as well as at helping them express their opinions, dreams, and ideas in an experimental way, from audio recordings to newspaper contributions. On Sunday, September 15, the children’s newspaper Tohle nejsou blbosti (This is not baloney) was launched. The newspaper was the result of the intensive work of the children’s editorial team, which met from June to August 2024.

What I appreciate in the format of this biennale is how it seriously takes into consideration the question of what is work/labor? in the context of farming, ecological resistance, military invasion, reproductive/care work, and artistic practice. I can see how the artwork itself and diverse ideas of engagement in culture are being deconstructed within the exhibition and in relationship with the public and educational programs, and I do consider it inspiring, especially as most of these projects have been living and will hopefully continue doing so outside of the context of the biennale, with trials and errors and various communal notions of success or failure. I only hope that as artists working with communities, we can continue learning to negotiate and loosen up our own egos, and maybe, as cosa.cz, venture on to establish cooperatives or garden sites ourselves, diversifying what art systems can mean and be.

Weronika Zalewska – artist, researcher and poet based in Warsaw. She practices video art and installation as a way of telling stories at different scales, at the intersection of documentary and speculative fiction. She is affiliated with the Bureau of Post Artistic Services. Her work has been shown at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, BWA Dizajn in Wroclaw, Arsenal Gallery in Bialystok, SKD in Dresden and the Performing Arts Biennale in Vilnius. Co-translator of Undrowned. Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals by Alexis Pauline Gumbs to Polish (Współbycie Publishing).

[1] https://www.ngprague.cz/en/event/3956/matter-of-art

[2] https://matterof.art/events/performance-olia-sosnovskaya-elske-rosenfeld-archive-of-gestures-becoming-in-visible

[3] https://matterof.art/events/performance-kateryna-aliinyk-the-inability-to-share-grief-is-not-as-bad-as-the-inability-to-share-beauty

[4] https://matterof.art/events/artistic-intervention-by-the-stopgenocidevgaze-collective

[5] https://matterof.art/events/vernaculars-of-resistance-guided-tour-with-artists-and-curators

[6] https://matterof.art/2024/artists/davra-research-group

[7] https://matterof.art/2024/artists/kateryna-aliinyk

[8] https://matterof.art/2024/artists/antje-schiffers

[9] https://matterof.art/events/uprooting-ill-health-i-talks-the-institute-of-anxiety

Artists: Kateryna Aliinyk, Zbyněk Baladrán, Björnsonova & Nik Timková, Zuzana Žabková, Vojtěch Hlaváček, Tamara Antonijević, Tanja Šljivar, cosa.cz, cultural cooperative & Viktor Vejvoda, DAVRA research group, Martina Drozd Smutná, Giorgi Gago Gagoshidze, Uladzimir Hramovich, Adelita Husni Bey, Nikita Kadan, Kateřina Konvalinová & Judita Levitnerová, Kateryna Lysovenko, Asunción Molinos Gordo, Pınar Öğrenci, Natalie Perkof, Marta Popivoda, Randomroutines, Alicja Rogalska, Elske Rosenfeld, Zorka Ságlová, Antje Schiffers, Olia Sosnovskaya, Petr Štembera, Dominika Trapp, Tomáš Uhnák with Asia Dér, Tamás Kaszás, stopgenocidevgaze collective (Yara Abu Aataya, Lynda Zein, Epos257, Kajetán Adler Jablonský, Vladimír Turner, Irena Lehkoživová, Jaroslava Tomanová, Tomáš Kajánek, Sany, Shawky Gamal)

Exhibition Title: Biennale Matter of Art

Curated by: Aleksei Borisionok, Katalin Erdődi

Venues: National Gallery Prague – Trade Fair Palace, Lidice Gallery, Kolektor Cafe, Jednorožec Farm, Psychiatric Hospital Bohnice, Center for Contemporary Arts Prague, Museum of the Cooperative Association of the Czech Republic, Chemapol, Petrohradská kolektiv, Kino Ponrepo

Place (Country/Location): Prague, Lidice, Roblín, Czech Republic

Dates: 14.06 – 29.09.2024

Photos by: Tereza Havlínková, Jonáš Verešpej