Lizaveta German

It is not always easy nor necessary to pin down who was the first to do something when it comes to art history. However, classical textbooks and the generally accepted hierarchy of the discipline generously offer such assumptions (like who was the first to paint this or that, or develop a certain style or technique, etc.). If we think of the post-World War II decade in Soviet Ukraine, is it clear who was the first artist to call herself a non-conformist and shift one’s practice against the social-realist canon? Or, if looking at the first years of Ukraine’s state independence, who could be legitimately called the first curator when the very word was staunchly avoided at first due to its association with the KGB, whose undercover agents “curated” certain controversial groups within the USSR, especially in intelligentsia circles (not to mention that those agents were also nicknamed “art critics in civilian clothes,” so the spheres of art and surveillance practitioners were linguistically intertwined in a strange way).

If we look at the most recent and clearly chronologically outlined chapter of Ukrainian art history, it would be statistically fair to credit that the first art exhibition after the full-scale russian invasion of Ukraine was opened on March 3, 2022, in Kyiv. Less than a week after not only Ukraine’s capital city, but the whole country, woke up from heavy missile explosions. Nikita Kadan, one of the most internationally renowned Ukrainian artists, found temporary shelter in the basement of Voloshyn Gallery in downtown Kyiv. After several days of sleeping on a mattress, he invited himself to the gallery’s storage and shuffled some pieces around the space. An intimate painting of 1990s New Wave star Oleg Holosiy complimented works of semi-forgotten 1970s artist Konstantin-Vadim Ignatov. Together, they suggested an unexpected dialogue with contemporary artists like Lesia Khomenko, Vlada Ralko, and Oleksii Sai (we may call it a coincidence, but this show united the works from several periods we are going to further focus on here). The exhibition’s title was Tryvoha – in Ukrainian, the word means both anxiety and (air) alert. Kyiv was empty and under strict military surveillance in those first weeks. Only a couple of people, namely artist and writer Yevgenia Belorusets and her parents, dared to attend the show. Kadan refers to them as witnesses, not spectators. And, in his own words, was inspired rather than disappointed by the fact that his show “lacked spectators’ presence.” “It seemed” – as Nikita recalls in 2024 – “when you have no guarantees of physical survival, here comes the time to do something about art, what seemed to be the most unnecessary and surplus sphere. And such a surplus kind of activity turned out to be extremely satisfying.”[1] Soon after, Kadan left Kyiv for Ivano-Frankivsk, one of the safest cities at that moment. There, he joined the lightning-fast organised residency called Robocha Kimnata (Working Room), curated by Lesia Khomenko and managed by the team of Asortymentna Kimnata (Assortment Room) art space.

On February 24, 2022, two female leaders of this independent institution (Asortymentna Kimnata), Aliona Karavai and Anna Potiomkina, found themselves in front of a local voinkomat (army recruiting centre) in a long cue of other would-be volunteers, looking to sign up for any possible services that the army might need. They were kindly advised to go back home and be helpful by doing what they were best at. And so they did – they focused on coordinating the evacuation logistics of heritage objects from the endangered regions and helped internally displaced artists establish themselves, even if only temporarily, in Ivano-Frankivsk. One of those artists was Lesia Khomenko, who came up with the idea of the residency. “At a time when physical destruction reigns, we will physically produce,” commented Lesia, “culture and art are important at any time. I already had a chance to get proof during the Revolution of Dignity. This is not a matter of first aid; it has nothing to do with survival, but it is very important at the diplomatic and geopolitical level.”[2] The residency didn’t simply give these artists shelter and workspace, it also brought back their sense of purpose and unity, even remotely. For instance, Katya Buchatska participated from Lviv. Regular online meetings, discussions, and a joint work frame helped her pull herself together and regain some meaning to her artistic practice instead of infinitely scrolling the social media feeds as we all did then.

In the case of Robocha Kimnata, diplomatic influence was not just an empty sentiment. On June 4, 2022, after the residency ended and most artists left Ivano-Frankivsk, the summary group show was opened in Asortymentna Kimnata’s own space. A month later, on July 9th, it was moved to and presented in Berlin (A:D: Curatorial space), with a small spin-off show in Maribor in late June and a subsequent stop in Essen in September (Museum Folkwang). Even for Ukraine, where independent managers and curators are pretty used to working enthusiastically under strenuous conditions (in the pre-war era, this could be defined as poor funding and precarious working conditions), this was a concise time frame for supporting a new production, putting a group show together, and setting it off on an international tour.

Back in Kyiv, a strive to be helpful beyond the army and a need to act quickly without the time to wait for institutional backing inspired a group of friends and colleagues (myself included) to gather for a Zoom call on the third day of the full-scale invasion. We brainstormed about what can be done and how to process the countless and quite chaotic offers of help and donations from all over the artworld. This is how the Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund was created and registered (and here I will allow myself to point out that all the legal and banking paperwork was settled much faster in a country at war than it would usually take in any peaceful “Western” country). Thanks to the new, fully legal NGO run by experienced insiders from the local art scene who mostly remained in Ukraine (myself excluded), dozens and dozens of artists and small organisations received much-needed financial aid without bureaucratic hassle. In parallel, the foundation started accumulating a digital (and soon material) collection of wartime artworks that will be donated to the future museum for contemporary art whenever it is opened.

These three cases – the self-organised exhibition for no audience, a residency to give food and solace for relocated artists’ guts and thoughts, and a rapidly established funding body and archive – are different in their nature and missions, but together (and this list of initiatives can be expanded) they demonstrate a pattern that has been visible since the full-scale invasion. While Kadan’s exhibition was produced as a gesture of counter-necessity, UEAF, on the contrary, emerged as a pure manifestation of practical urgency. The Ivano-Frankivsk residency, perhaps, combined those two approaches: the institution made the most of its geographically fortunate position in the West, as well as of the tirelessness of its leaders by giving safe physical and mental spaces to those in need. They proved that talking about and producing art can be a good coping strategy when nothing else works. One can look to these activities in times of unimaginable crisis as an unavoidable necessity. But I prefer to count them as an optionality that could have been but was not ignored.

The cases above, along with many other shows and projects that I will only partly cover here, serve as a convincing illustration of this essay’s main idea: that self-organised artistic life and practice in Ukraine did not cease on February 24, 2022, but it has, to the contrary, been experiencing a qualitatively new level of engagement and public interest. I argue that it is, first and foremost, the longer tradition of grassroots work that has kept the scene alive recently. Apart from those mentioned in the prologue, many cultural practitioners have established opportunities for representation despite the circumstances, without relying on the pre-war infrastructure or any predictable support. Many state institutions have remained closed since the war started, and their function has been reduced to protecting collections and buildings. Meanwhile, independent collectives, NGOs, and informal artistic assemblies have continued their work. The phenomenon of the apartment gallery (Mizhkimnatnyi Prostir in Lviv, Kruchi and Depot 12_59 in Kyiv) and the apartment exhibition (i.e. those curated by Oleksandra Pogrebnyak, Nikita Kadan and Anton Saienko, Kateryna Iakovlenko, Ola Yeriemieieva, Sasha Chepelev and Zhenia Kriuk, and others) has become relevant again, as it once was in conditions of Soviet censorship. Independent artistic residencies function all around Ukraine, from the relatively peaceful Carpathian region (Khata-Maisternia in Babyn village, Sorry No Rooms Available in Uzhhorod) to the Kharkiv region next to the front line (Art Kuzemyn residency) and even secretly in Kherson under russian occupation (coordinated by Yuliia Manukian offline and later online). Finally, the first museum for contemporary art (initiated by an NGO behind the above-mentioned Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund, not the government) opened its inaugural show in the former Lenin Museum in Kyiv, which is now the Ukrainian House. As artist and curator Stanislav Turina wittily said, Ukraine has experienced “a counteroffensive of exhibitions.”

My approach to trace the above-mentioned longer tradition of grassroots work from Ukraine’s recent art history is to zoom in on its separate episodes when a similar “counteroffensive” was engaged, even if not always visible to the audience outside the circle of peers. These episodes are practices of the Sixtiers, the first post-war generation which experienced relative civil and cultural liberation after Khrushchev’s Vidlyha (the Thaw) in the 1960s; non- or semi-institutional exhibitions in Kyiv, Odesa, and Lviv in the first years of state independence in the early 1990s; and off-spaces and self-organisation movements of the early 2010s.

What do these three periods conceptually share between one another and with the present moment? It is an intensive search for strategies of alternative artistic representation to oppose established art infrastructures and policies (or to oppose the situation of their absence). Or, to put it simply, it is a strive to break free from the limitations, conformism, or institutional entropy under different political circumstances: the Soviet regime during the 1960s, the turbulence of the immediate post-USSR transitional period in the early 1990s, the stagnant years on the eve of the Revolution of Dignity (2013–2014). And today, it is the full-scale war.

What were those strategies and representation modes for the outlined periods? In the case of the Sixtiers, artistic infrastructure in Ukraine (as in the rest of the USSR) was completely state-controlled. The official institutions like the Artists’ Union or the Art Kombinat were generous to professionals who worked according to the communist party agenda but were ideologically hostile and restricting towards those willing to stay outside of the socialist realist canon. Bureaucratic procedures and rigid expertise committees (vystavkoms) made it impossible to publicly exhibit (print or perform) art that was not approved. However, working entirely autonomously from this state system was also impossible – the Artists’ Union membership was an indispensable condition to gain access to professional earnings. So, in many cases, the strategy to sustain a free artistic practice in the Sixties rested on a balance between official form and non-official content in disguise.

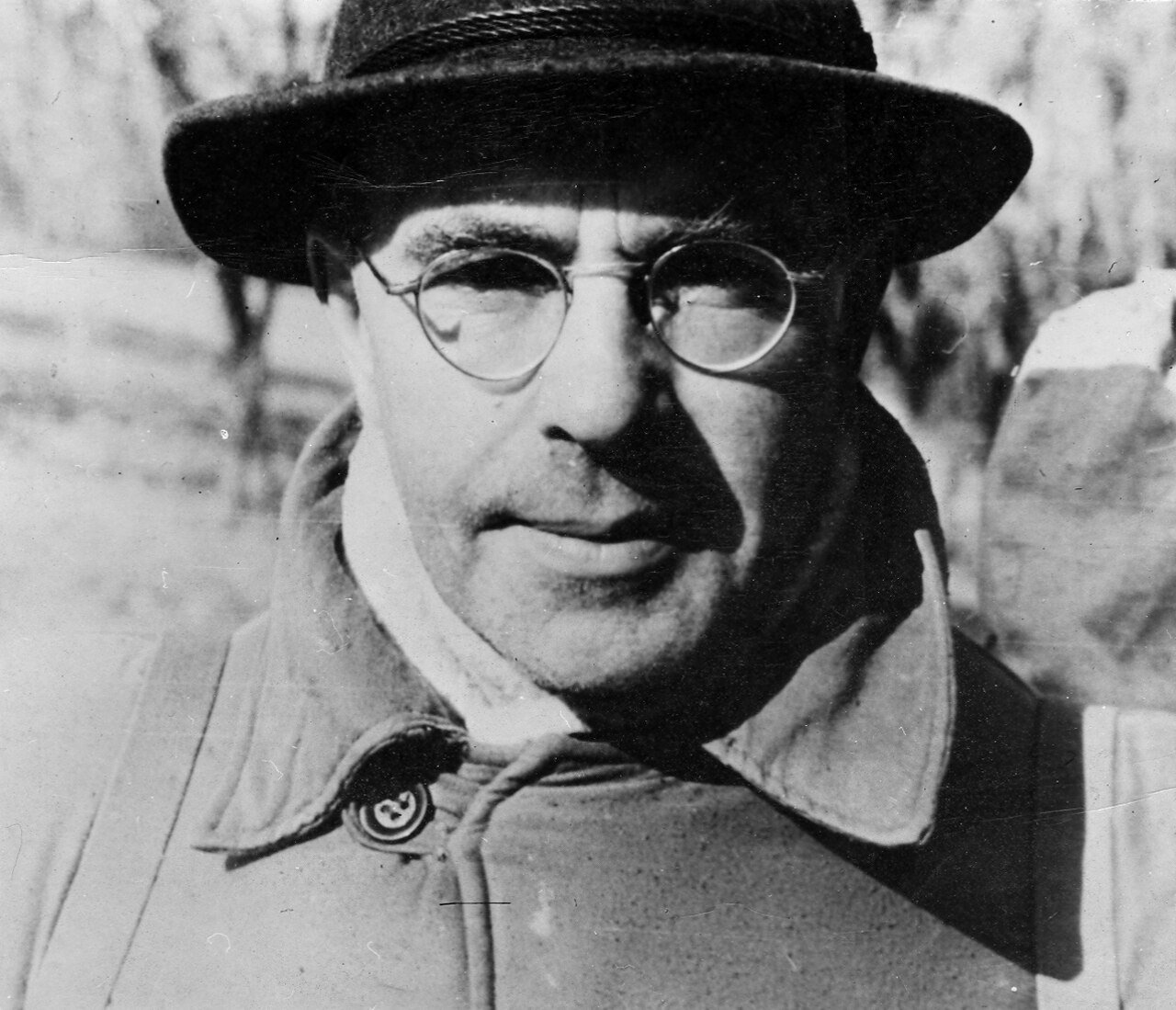

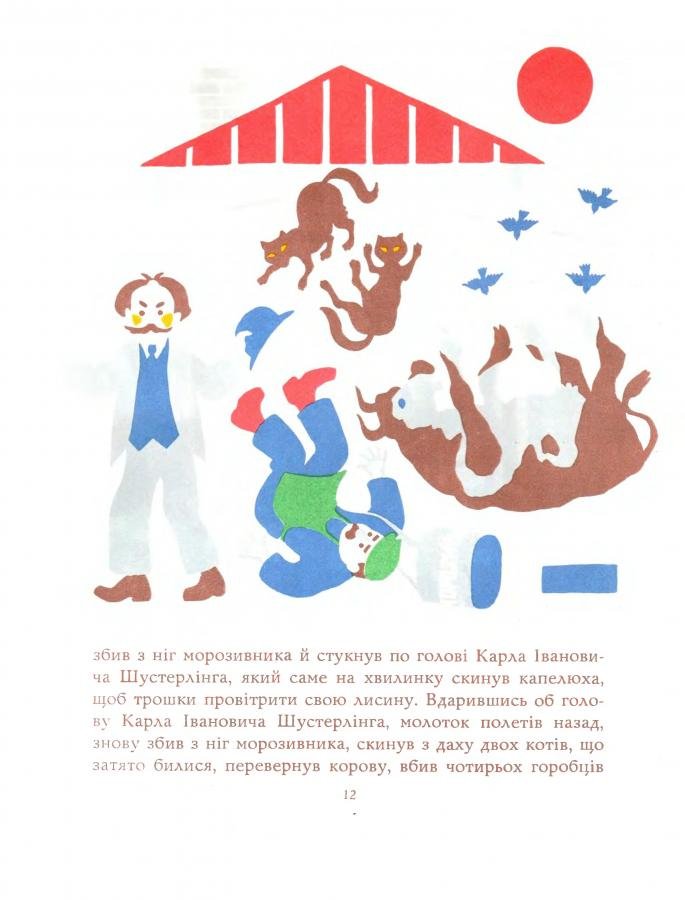

In the case of the Sixtiers artists, the strategy of alternative representation was to find loopholes in the system and hack it. For example, abstract motifs were banned in painting, sculpture, or graphics, yet they were incorporated into a monumental mosaic commissioned by the state or in children’s book illustrations, spheres with lesser aesthetic censorship. For example, Hryhorii Havrylenko was known as a book graphic who illustrated around 35 pieces, primarily Ukrainian poetry and children’s literature. He consequently moved from realistic and narrative ink drawings towards colourful linocuts, which resembled the style of his nonfigurative paintings. Unable to exhibit the latter during his lifetime, Havrylenko only showed his abstractions to a limited group of friends in his tiny studio on Honchara Street in downtown Kyiv, elements of which were transferred to a “legal” medium of mass-published books. Certain aspects of geometrical colour structures migrated from his canvases to his books, as in the case of the red circle that turned into a sun in illustrations for Daniil Kharms’s fairytales.

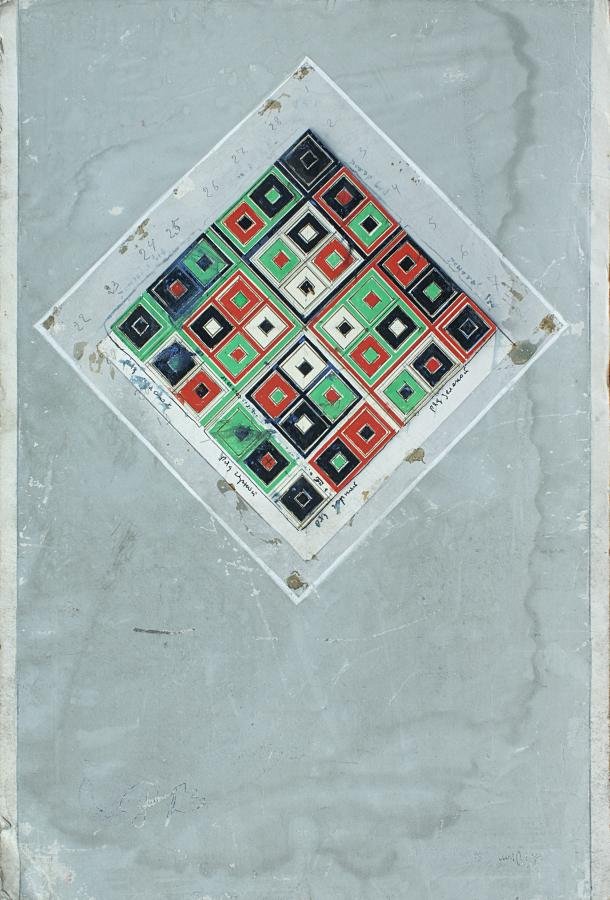

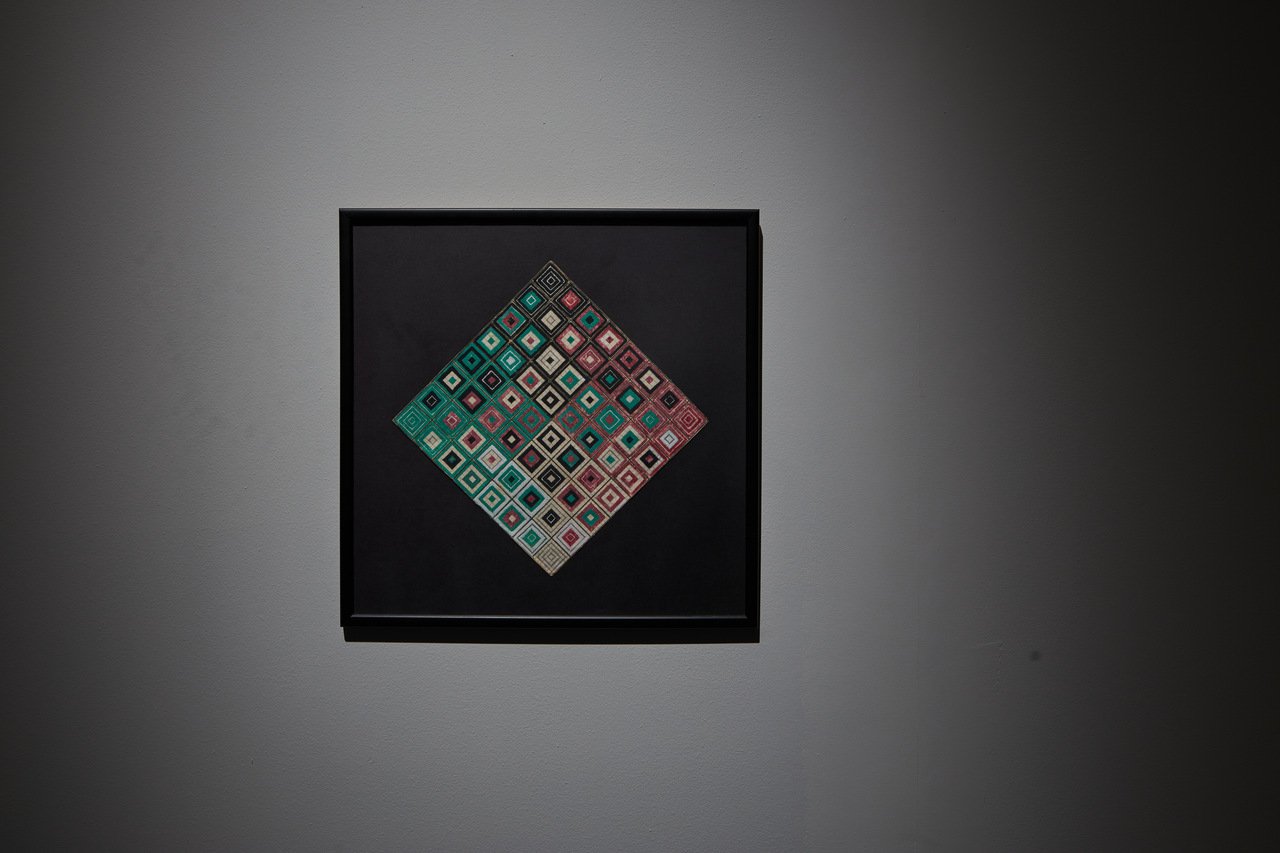

Valerii Lamakh used a similar strategy. He was one of the most in-demand poster designers, and later monumentalists, of his time. He completed several celebrated mosaic panels in Kyiv, Mariupol, and Ternopil in collaboration with Ivan Lytovchenko and Ernest Kotkov. Both posters and mosaic art were, of course, the most politically informed and state-controlled art forms in the USSR. Yet, in his private time, Lamakh was working on something opposite in concept but in a way, also monumental in scale. Between 1968 and 1974 (his death), he drafted five volumes of the so-called Books of Schemes, a theoretical work with the artist’s interpretations of the world’s visual culture evolution. His ideas were enforced and illustrated by geometric drawings and schemes. The book was published only in 2015, after three decades of structuring and editing by Valerii’s wife, artist Alina Lamakh. Similar to his close friend Havrylenko, Lamakh revealed his writings only to a trusted circle of like-minded friends but managed to smuggle some elements of his schemes into mosaics on the walls of the Ternopil cotton factory and the Chemist Palace of Culture in Dneprodzerzhinsk.

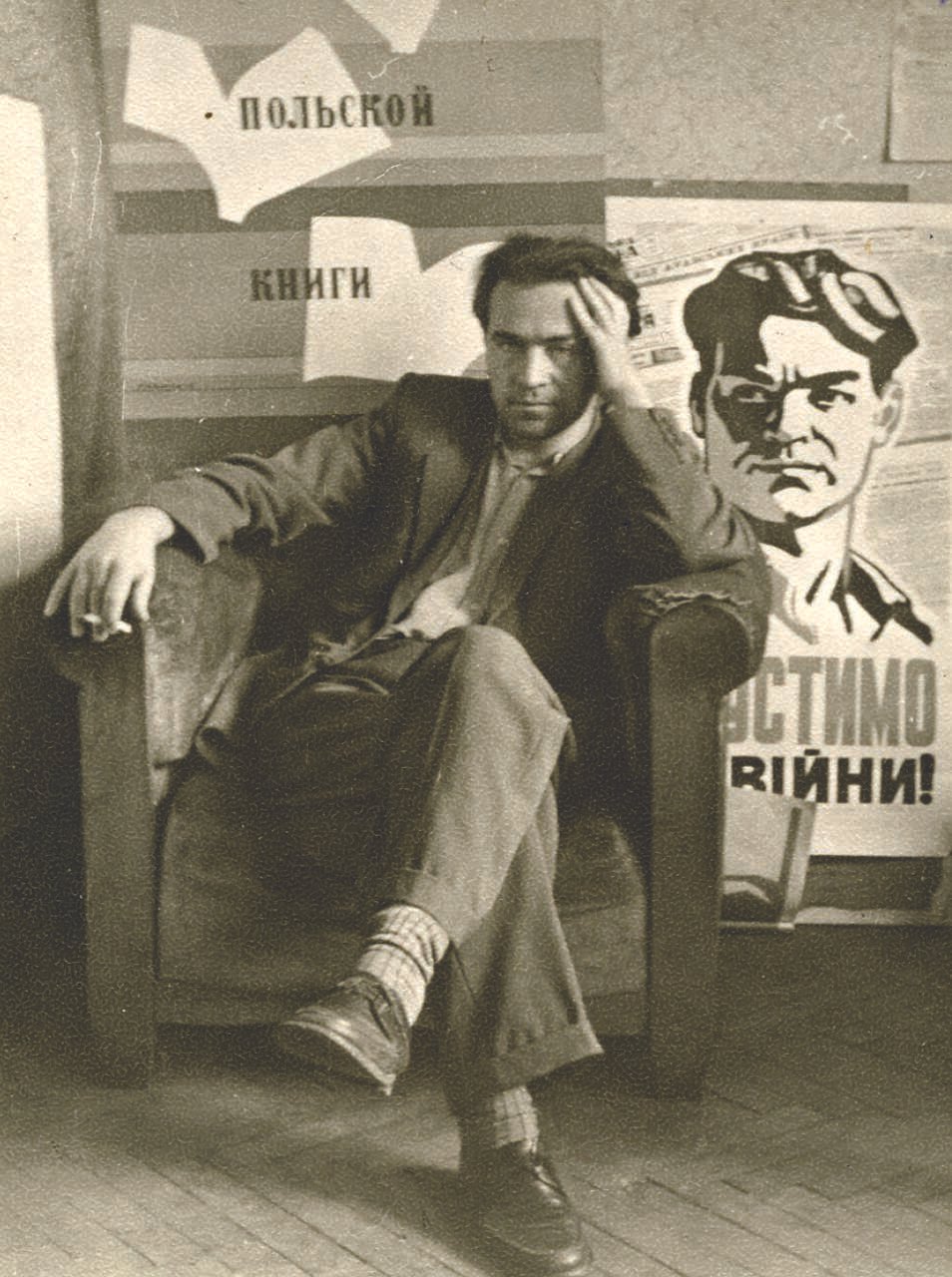

In several memoirs, and fewer expanded art reviews, such as the one written by Borys Lobanovskyi, Kyivan artists, poets, musicians, and filmmakers formed interrelated circles or triads. Lamakh and Havrylenko belonged to a triad with poet Gennadiy Aygi, one with composer Valentyn Silvestrov and one with film director Sergei Paradjanov and artist Vilen Barskyi. It doesn’t mean these and other artists’ friendships and professional exchanges were limited to a few peers. Naturally, parties and more crowded gatherings were typical business, yet deeper connections and profound professional conversations happened in what Lobanovskyi called spiritual micro-groups. Altogether, the art historian described this generation as “Kyiv Anchorites” in his eponymous milestone text. He referred to an institute of monastery hermitage rooted back in Kyivan Rus’ times to describe how the Sixtiers nourished their isolated artistic careers and shared ideas under the scrutiny of censorship. For Lobanovskyi (himself a member of those circles), the hermitage “guaranteed artists their freedom without forcing it onto anyone else”, and the solitude was a method to consolidate energy and, I allow myself to end his sentence, to save themselves from struggling with the system that they believed couldn’t be fought and killed. So, the Kyiv “counteroffensive” of the Sixties can be summarised as a community of artists with an intense intellectual interexchange, whose fruits of labour were partly undercover and never reached a more expansive public than a narrow group of politically and intellectually trusted people. Yet today, we have a right to refer to their actions as a consolidated and articulated scene with its own established methods of public representation (through books and mosaics); a rich oeuvre that only in recent decades has gradually started to be exhibited.

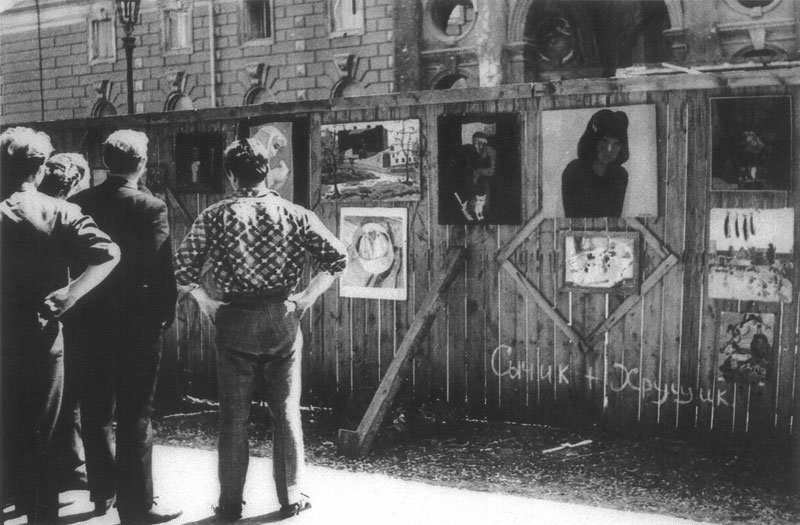

Opposite to “anachoretic Kyiv” was the informal art scene of the eternally extroverted city of Odesa. As a symbolic start of the local Sixtiers chapter, one can look to the genuinely legendary, yet still obscure exhibition of Stanislav Sychov and Valentyn Khrushch – the so-called Fence Show. Its obscurity is defined by a lack of proper documentation and even basic recorded facts. According to Kateryna Filyuk, at least three different months in 1967 are mentioned by different scholars as when the two artists voluntarily hung their paintings on a construction fence around the Opera Theatre in the heart of Odesa. There’s no list of works displayed, no clear evidence of the show’s duration and its consequences for the installers (we know that it lasted no more than a day), and only a few photographs of it are left.[3] Despite such limited factual knowledge, the show rapidly became one of the most durable myths of the Odesa art scene, reinforced by several attempts to recreate it: unfortunate ones (in 1977, Yevgen Rakhmanin’s and Viktor Rysovych’s version was shut down by the police within 45 minutes) as well as successful ones (in 1997, the New Art Association mounted Sychyk + Khrushchyk showing next to the same opera house which was, ironically, hidden behind a fence again).

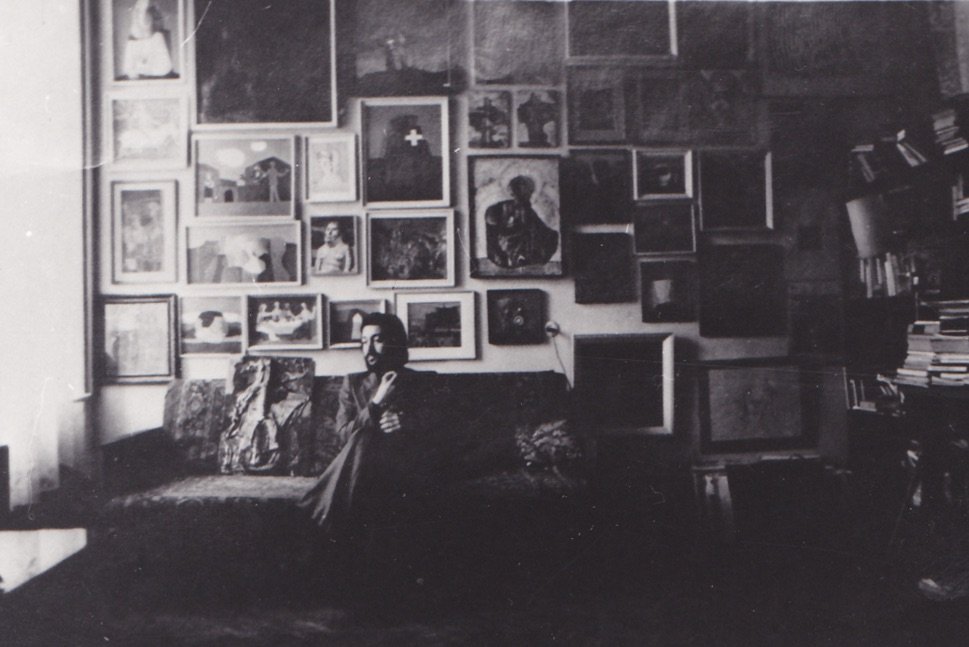

Sychov and Khrushch were not the sole warriors of underground Odesa. Artist Oleh Sokolov, “the first [Odesan] artist to confront – all on his own – the banalities of Soviet official art,”[4] according to Tetiana Basanets, was famous during the 1960s for his weekly salon-style apartment gatherings every Wednesday (Sokolovian Wednesdays), the establishment of the Mikalojus Konstantinas Ciurlionis informal club, and the mural “To the Victims of Stalinism” that he created in his apartment in 1964. Later on, during the 1970s, there was a peak in the so-called apartment exhibitions – a community-driven phenomenon in Odesa that had no other equivalents in Ukraine at the time. As a journalist and active member of the community, Yevhen Holubovskii recalls both artists themselves (Viktor Maryniuk and Ludmila Iastreb, Oleh Voloshinov, the Anufriev family) and collectors (Volodymyr Asriev, the Velikanov family, and others), lent their houses for semi-open exhibitions. The apartment of Volodymyr Asriev, a musician then, was one of the most popular “exhibition halls.” The spacious room with walls about 4,5 meters high and bay windows could accommodate many small and medium-sized paintings and graphics. The fact that Asriev’s place was right next to the KGB office added a particular zest to each event.[5] Most probably, those gatherings were no secret for the KGB. No one made a big deal of surveillance, as several participants of the shows recollected in our private conversations – the people of Odesa never lost their deeply rooted joie de vivre and cherished time spent together, no one gave a damn about the consequences. So, apartment exhibitions were not only about an urge to exhibit and be seen as artists, but also to come together as a community.

The fascination with Fence Show and apartment shows by the next generations of local artists, as Filyuk goes on, was perfectly understandable, even when Soviet censorship ceased to exist. Ihor Gusev, the leader of the Art Raiders group, staged performances at the Starokinnyi Market from 2007–2009 and was also likely influenced by the spirit of the non-official communities of their predecessors. So were Dmytro Dulfan and Serhiy Poliakov, who established the Okno Gallery in a small wine store by the Novyi Rynok (New Market). “[…] it becomes apparent – summarises Filyuk – that Sychyk and Khrushchyk had let the genie out of the bottle; they laid the foundations for the era of apartment shows that allowed an entire generation of Odesan artists of the 1960s – 1980s to obtain acclaim and feedback. It gave grassroots art movements the impetus that reverberates in Odesa even today.”[6]

The cases mentioned above, of shows at occasional non-professional venues such as flea-markets and wine shops in post-soviet years can be explained by the eccentricity of their initiators and a banal absence of any other possibilities. After the USSR collapsed, the state-controlled soviet ideology de jure stopped limiting artists in their expression. However, the state-owned infrastructure de facto stopped operating and left some dysfunctional vestiges like the Artists’ Union with a nominal rather than practical role in artistic life that started to flourish chaotically.

In Ukraine, no immediate replacement for the state infrastructure was established, neither in the form of public funding nor an art market – no restrictions, ideology, or canons and instead, complete freedom, zero budget, and extremely unconventional or half-abandoned premises – these were the preconditions for fulfilling exhibition ambitions for artists and pioneering curators in Kyiv, Lviv, and Odesa, who, in the 90s, found themselves amidst the ruins of the fallen epoch – in some particular cases, actual material ruins. “You have to understand what the 1990s [in Ukraine] were. This was a ruined country. So much was it in a state of decay that it would be foolish to ignore it and not work with it. Invasion of art into premises not adapted for this was a ready-made intervention, a strong aesthetic and social move in itself,” Oleksandr Roytburd recalled about his projects in the early state independence years.[7]

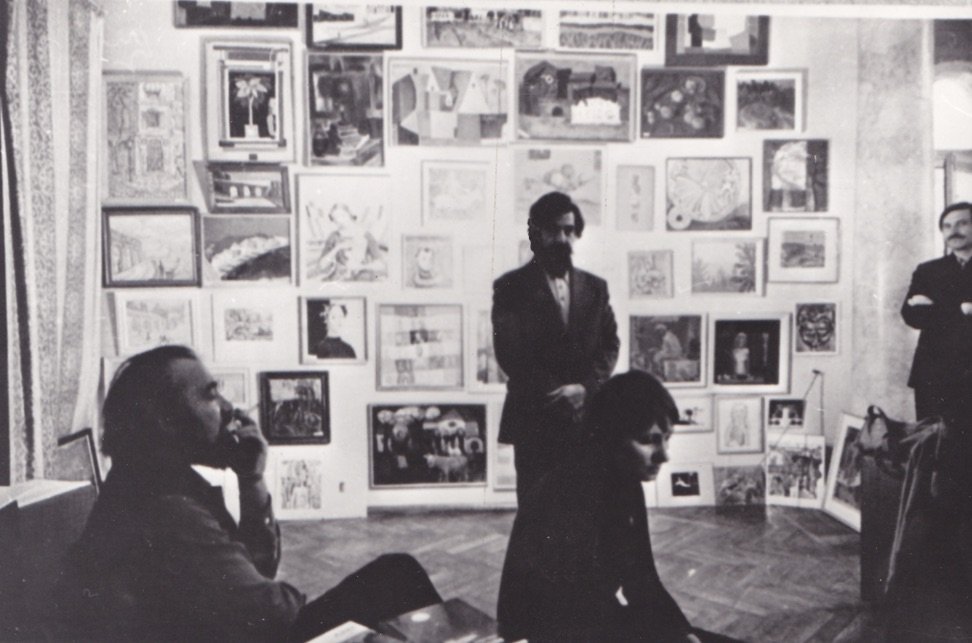

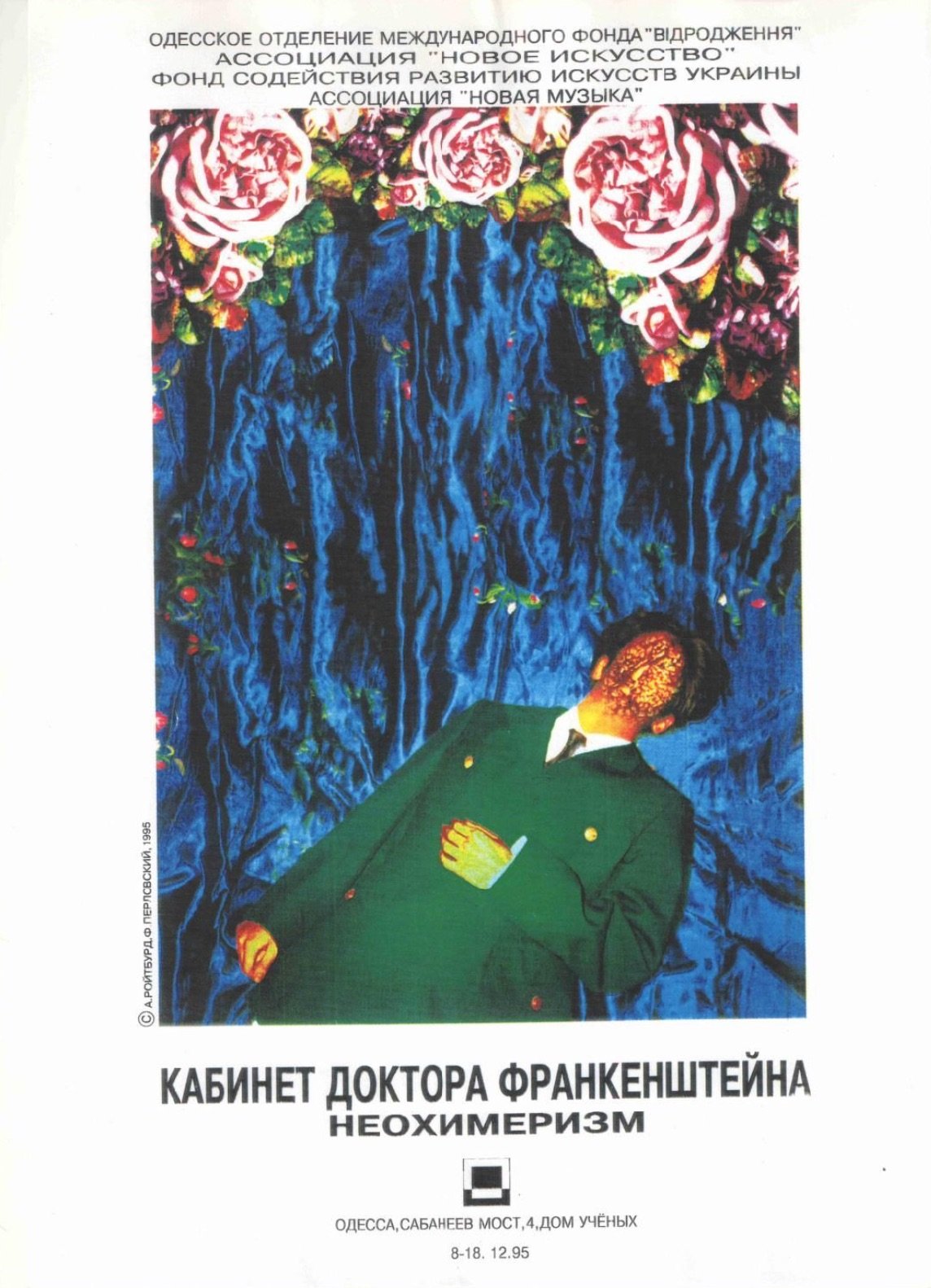

Roytburd, first and foremost an artist, was also among the early curators and organisers of exhibitions all around Odesa, including a series of group shows in a private art centre with museum ambitions called Tyrs (1992–1999), located in two rooms of the so-called Shakh Palace. The Neo Gothic interiors of the palace added specific vibes to every show. Roytburd described the primary curatorial method as the collective work and self-expression of tusovka.[8] Ideas, a list of participants, and exhibiting works were discussed and approved jointly. Self-presentation, self-organisation, and self-education were the words that best characterised the artistic practice of Odesans at that time.[9] Apart from Tyrs, Roytburd’s early significant curatorial endeavours included a trilogy of exhibitions roughly united by his interest in various psychiatric issues (such as alienation of the inner self under mass-media impact or an urge for violence) and their reflections on practices of contemporary, primarily local artists.

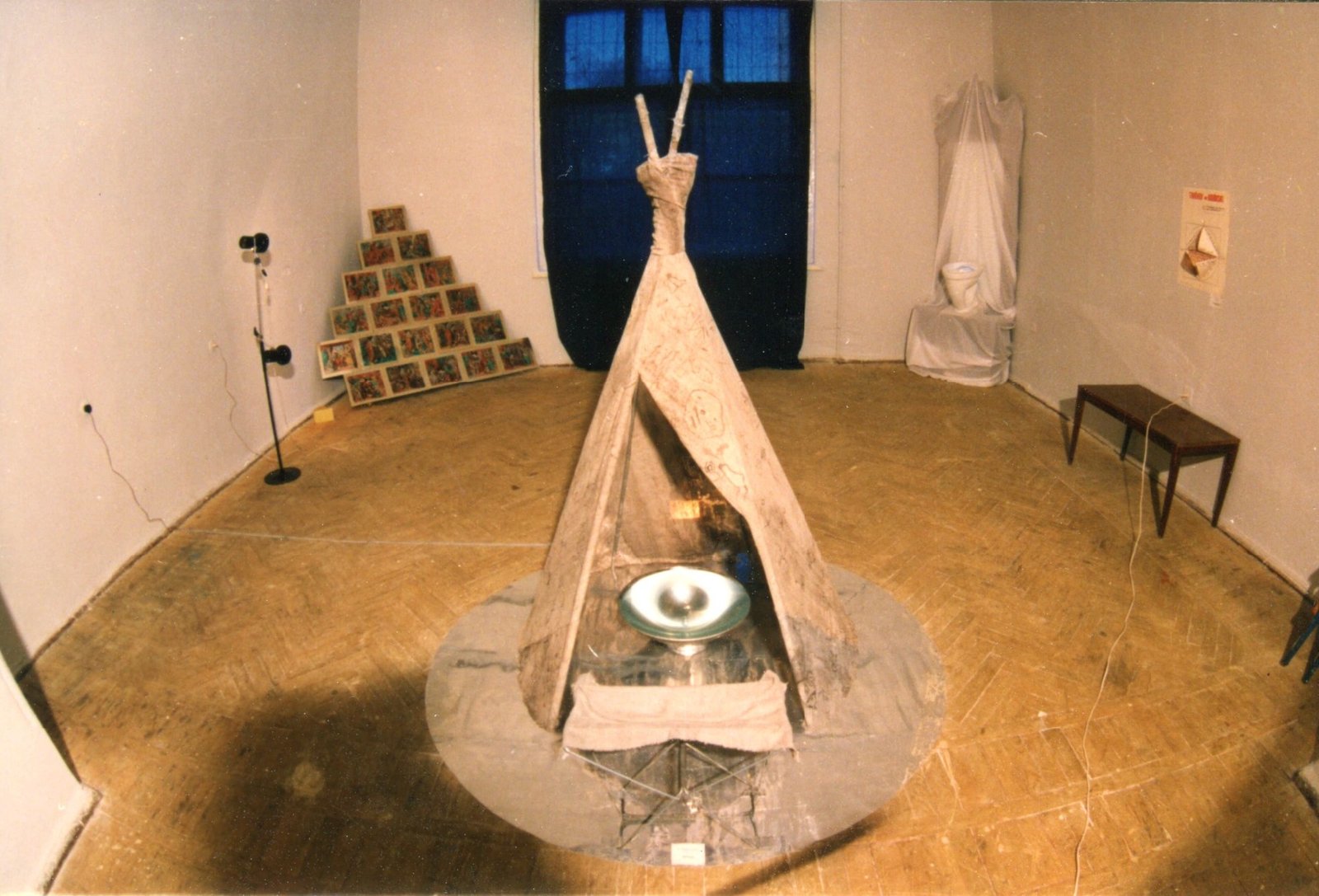

All three shows were installed at municipal, non-professional spaces: Kandinsky Syndrome (1995) occupied the halls of the local history museum. Doctor Frankenstein’s Cabinet. Neochimerism (1995) was located in the basement of the Odesa House of Scientists (the former estate of Count Tolstoy). The third one, Phantom-Operá, was in the Theater of the Young Spectators (the former small stage of the Opera House), overdecorated by oldish theatre attributes. All those venues had lost, temporarily or permanently, their initial functions desperately needed a renovation. However, they kept their grand interiors and held many useless objects, like restaurant equipment in an abandoned kitchen in the House of Scientists. For Roytburd, adapting and using those extra things was part of his artistic rather than curatorial logic. Altogether, he was driven by the idea of accommodating those ruins rather than avoiding them.

Another active curator and commentator of Odesa’s artistic life of the 1990s, Mikhail Rashkovetskyi, summarised the experience of the shows in the 1990s (including those co-curated by him) in a different, much more negative light: “The impassable ruin is the first and dominant element of the semantics of the local context that contemporary visual art of Odesa tries to connect with.”[10] For him, shabby and often stuffed spaces were not as much a source for exciting installation ideas but rather a forced move due to a lack of ordinary spaces.

Exhibition view, “The Cabinet of Dr. Frankenstein. Neochimerism” (Oleh Migas, “Consequences of Musical Performance”), 1995, Odesa House of Scientists, photo: Ihor Khodzinsky. Image courtesy of the Archive of the Museum of Odesa Modern Art, Odesa.

The motif of ruins was also relevant for Kyiv, which witnessed turbulent urban space transitions in the beginning of the 1990s. One of the most spectacular projects ideologically tied to a venue was the three-day exhibition Exploration of a Space, initiated by the artist Anatoly Stepanenko (May 12–15, 1993). The venue was the so-called Old Academic Building, an authentic and highly neglected monument of architecture from the 17th century, an unrenovated part of the recently reopened Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. All the works were visually discrete and inscribed into the space as responses to their specific locations. Stepanenko’s contribution was a dry, leafless tree that seemed to have sprouted in a hole in the wooden floor that had been filled with construction junk and earth. Another artist, Mykola Matsenko, created several “columns” from transparent cellophane tubes, which maintained their shape and vertical position thanks to the airflow from an ordinary vacuum cleaner. These unstable, pseudo-columns imitated the old vaults’ support system which underlined the semi-distressed building’s fragility. Matsenko’s artistic gesture, according to art critic Kateryna Stukalova, was rather a gesture of social meaning because “the principle of ruins” and “permanent renovation” in the show’s composition evoked apparent associations with the surrounding reality.”[11] The future fate of this particular ruin was lucky: a year later, it was renovated and eventually turned into an actual exhibition centre of the newly opened Soros CCA. Its founding director, Marta Kuzma, spotted the building during this very exhibition.

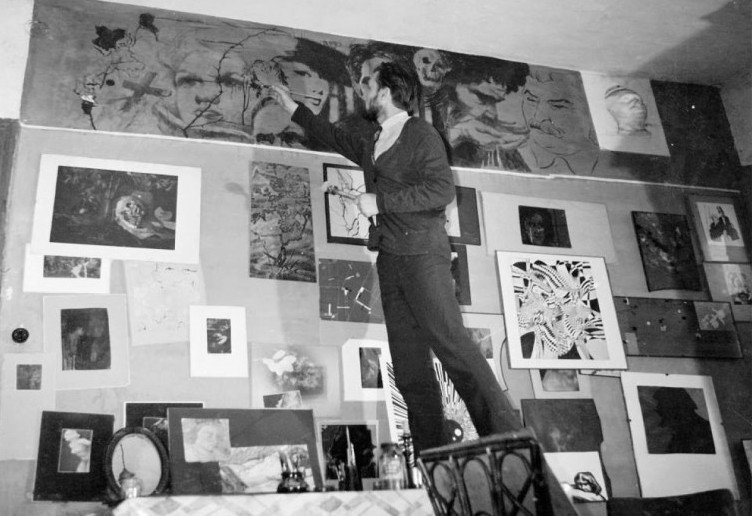

In Kyiv in the early 1990s, similar abandoned but quite livable buildings downtown were also squatted by artists. The first such venue at former Lenina Street was inhabited as early as late 1989 and existed until the summer of 1990. But the true informal headquarters of Kyiv art life was a constellation of several apartments in the magnificent building №18a at the former Paris Commune street (now Mykhailivska Street), that gave a name to the whole community around it. As art critics Alisa Lozhkina and Oleksandr Soloviev recalled, initially, young artists were obsessed with large formats and searched for big but cheap spaces to share and work in. But practical needs were not the only drive: “However, in addition to the urgent need for survival and creative self-realisation, [they] had an extra motivation for squatting – the desire to somehow outline the borders, even geographically, of their community in a still very conservative environment, to create an independent territory of new art. The ideal laboratory space was old multi-room communal apartments in houses with very high ceilings.”[12]

Inhabited by Oleg Holosiy, Lera Trubina, Oleksandr Hnylytsky, Vasyl Tsagolov, Yurii Solomko, Oleksandr Klymenko, Dmytro Kavsan and Leonid Varyvanov, Paris Commune squat, also known as ParKom, was the central – but not only – spot. Several streets around it, right between the central Maidan Nezalezhnosti Square, St. Sophia Cathedral, and Mikhailivskyi Square, became an area where other artists, including Arsen Savadov and Heorhii Senchenko, Illia Chichkan, Kyrylo Protsenko, Maksym Mamsikov, Illia Isupov, and others rented studios and apartments. Beyond their practical function (some artists not only worked but also lived there with their families), ParKom became a place of social magnitude not only for artists but also for all “cool youth of the city”…“musicians, poets, first IT people, fashionistas, first collectors, gallery owners; Western curators interested in the latest trends in post-Soviet art also began to come here.”[13]

A party place and collective open studio between late 1990 and 1994, the squat was a substitute for a centre for contemporary art. The first group shows of the ParKom circle was opened in old-school state exhibition halls under the operation of the Artists’ Union on Volodymyrska and the former Horkogo Street. But let’s quickly take a look back at the Odesa apartment shows and we can imagine a reverse situation: while the Sixtiers consciously created small works to exhibit in small apartments, artists of the 1990s could accommodate their huge canvases only on spacious state premises that had finally become available.

The first “summary” show was ironically called The Artists of Paris Commune (November 1991).[14] It was organised by Oleksandr Soloviov, who was right about to leave his permanent job as the head of the exhibition department at the Artists’ Union but still had access to its real estate (a good deal of which was soon after privatised or rented out for non-art purposes). Soloviov was Ukraine’s pioneering curator and active member of the ParKom circle. He described his path from bureaucratic work into contemporary exhibition-making: “We thought that we were moving into an abandoned house on Paris Commune street for a month only, but ended up staying for four years until we were evicted by new owners who had acquired the building. And I ended up being “an art critic at the squat”. And since I had to position myself and make a statement somehow, my activity grew into organising exhibitions. Fortunately, all the artistic processes took place in front of my eyes.”[15]

The last show at ParKom was The Space of the Cultural Revolution in 1994. It was organised in the former Lenin Museum (renamed Ukrainian House in 1992) as part of the first Kyiv art fair. The show was commissioned by Soloviov and orchestrated by artists Arsen Savadov and Heorhii Senchenko, who placed all the exhibits behind a wooden fence painted in pale red and installed along the perimeter of the upper floor hall with a void inside. Viewers could look at the works only through peepholes with distorted optics. The fence was the reason for many artists to cancel their participation, unwilling to make their works practically invisible. For Savadov and Senchenko, it was an object of its own, “a symbol of a cultural revolution that burned out” (hence, the red paint was pale, not bright) and a metaphor for a barricade that marked transitions in all aspects of life, art included.[16] This relatively heavy distinction of the exhibition space can also be interpreted as a need to distance oneself from an ideologically hostile exhibition venue when not many others were available. For why else did the curators have to hide the cold yet rather elegant marble walls of quite a newly built soviet museum (1982) behind a trashy fence? It was a kind of a ruin in its own right.

Except for a few neatly curated shows by another pioneer in the 90s, Valerii Sakharuk, the state-owned Ukrainian House in the city’s heart had not been used again for museum or exhibition purposes until the late 2000s. One of the reasons for that was purely economic, since the gigantic building required big budgets and administration to be sustained and adapted to artist’s needs. This venue’s history and transformations deserve a separate profound review, and its possible future arouses curiosity. Here, I only mention that during the recent full-scale war years, it has become one of the most active operating exhibition venues, mainly hosting guest projects rather than producing their own. It welcomed the retrospective of key Sixtiers artist Alla Horska, and How Are You?, a summary group show of contemporary wartime art. Despite the extreme popularity of some shows among the general audience, most of the guest curators have been criticised for their inability to absorb the space and conquer its “Lenin Museum aura.” As art critic Illya Levchenko wittily noticed, “[…] the desire to put [this venue] at the service of all “Ukrainian” is prevented by […] the logic of viewing the exposition – in circles around the dominant (already absent) figure of Lenin. The central space of the exhibition – the space of the absence of this figure – is perhaps the most difficult challenge for any curatorial vision (remember how Savadov and Senchenko separated artworks from this central void space with a fence?).”[17]

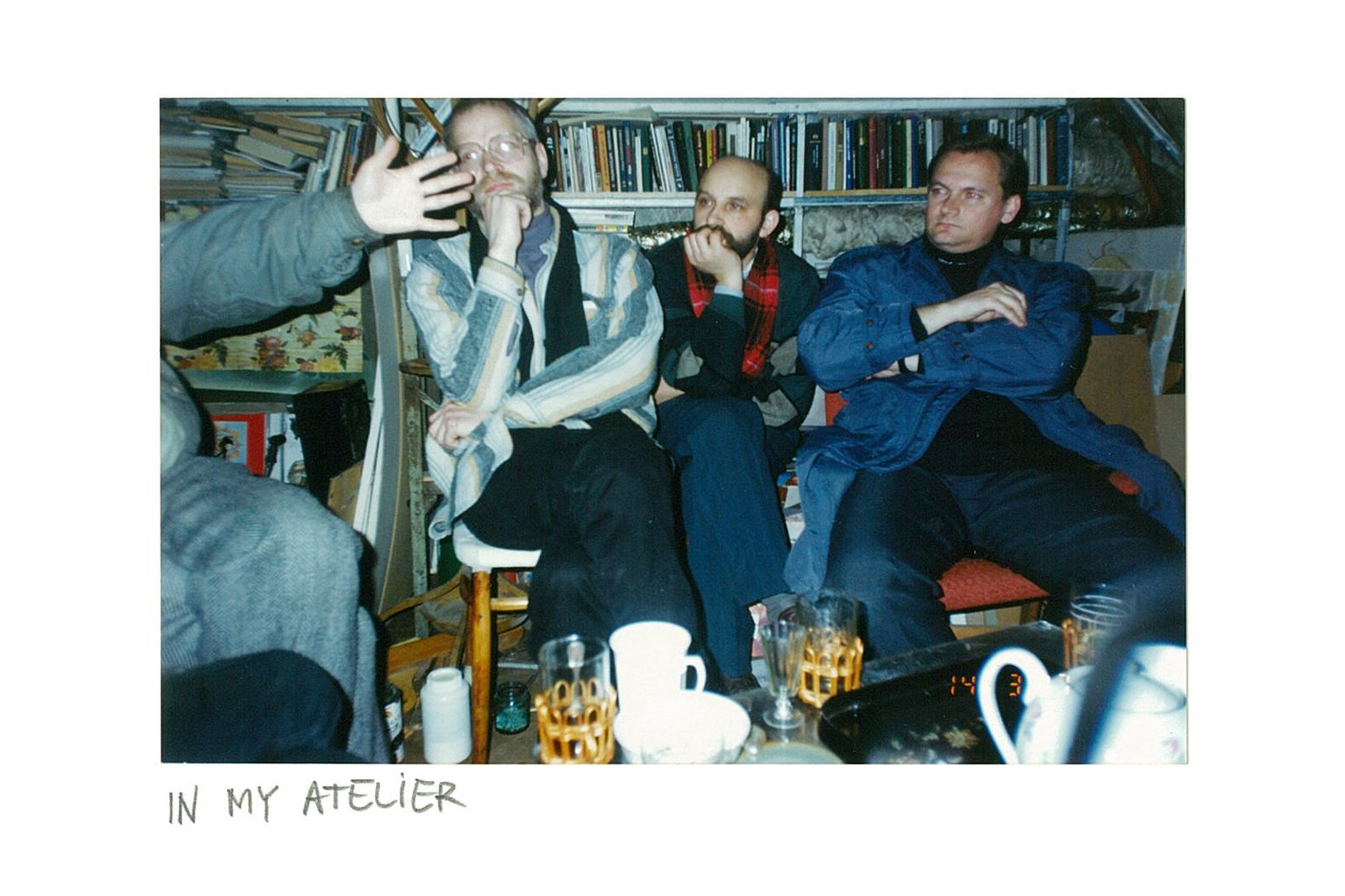

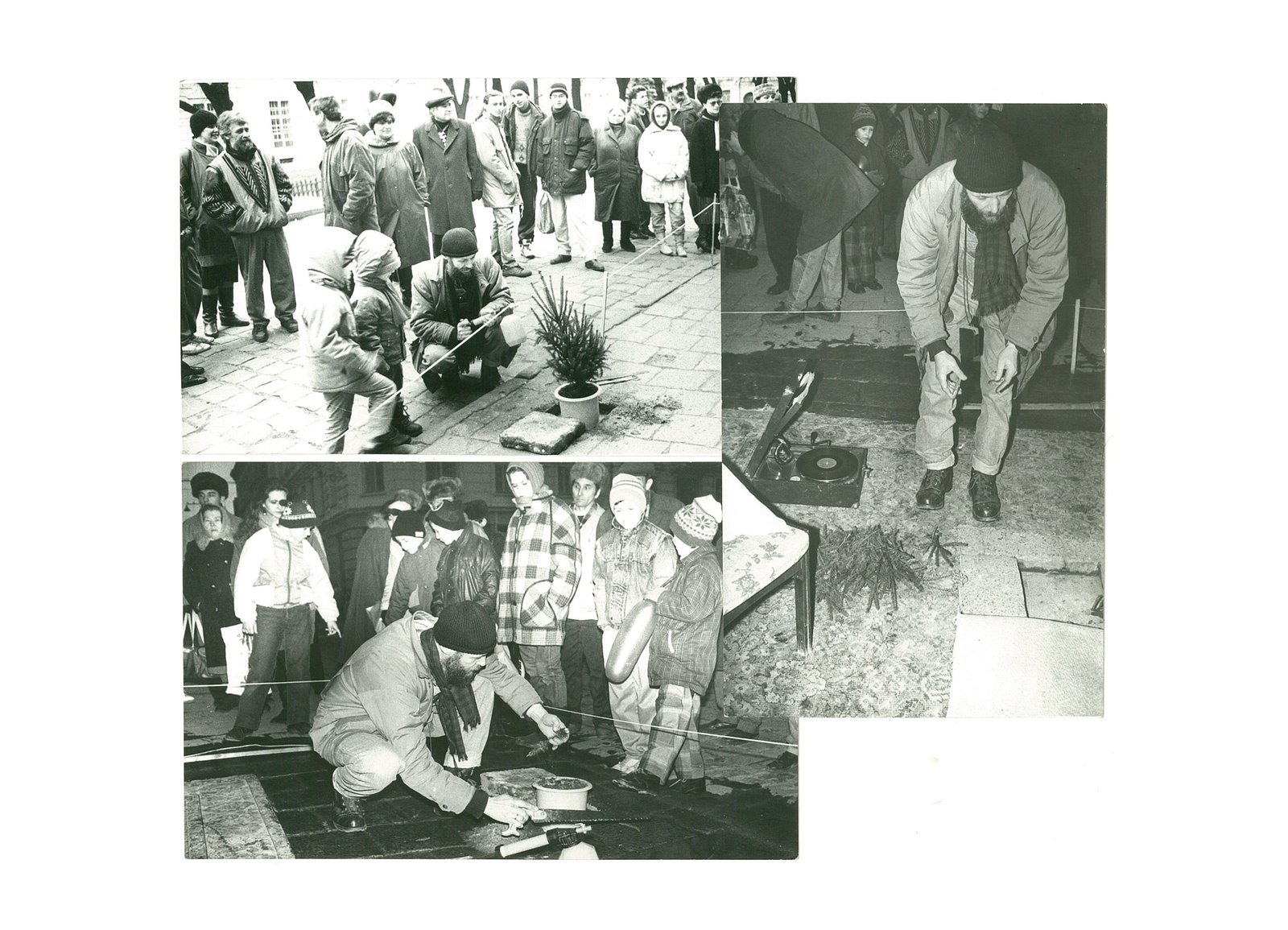

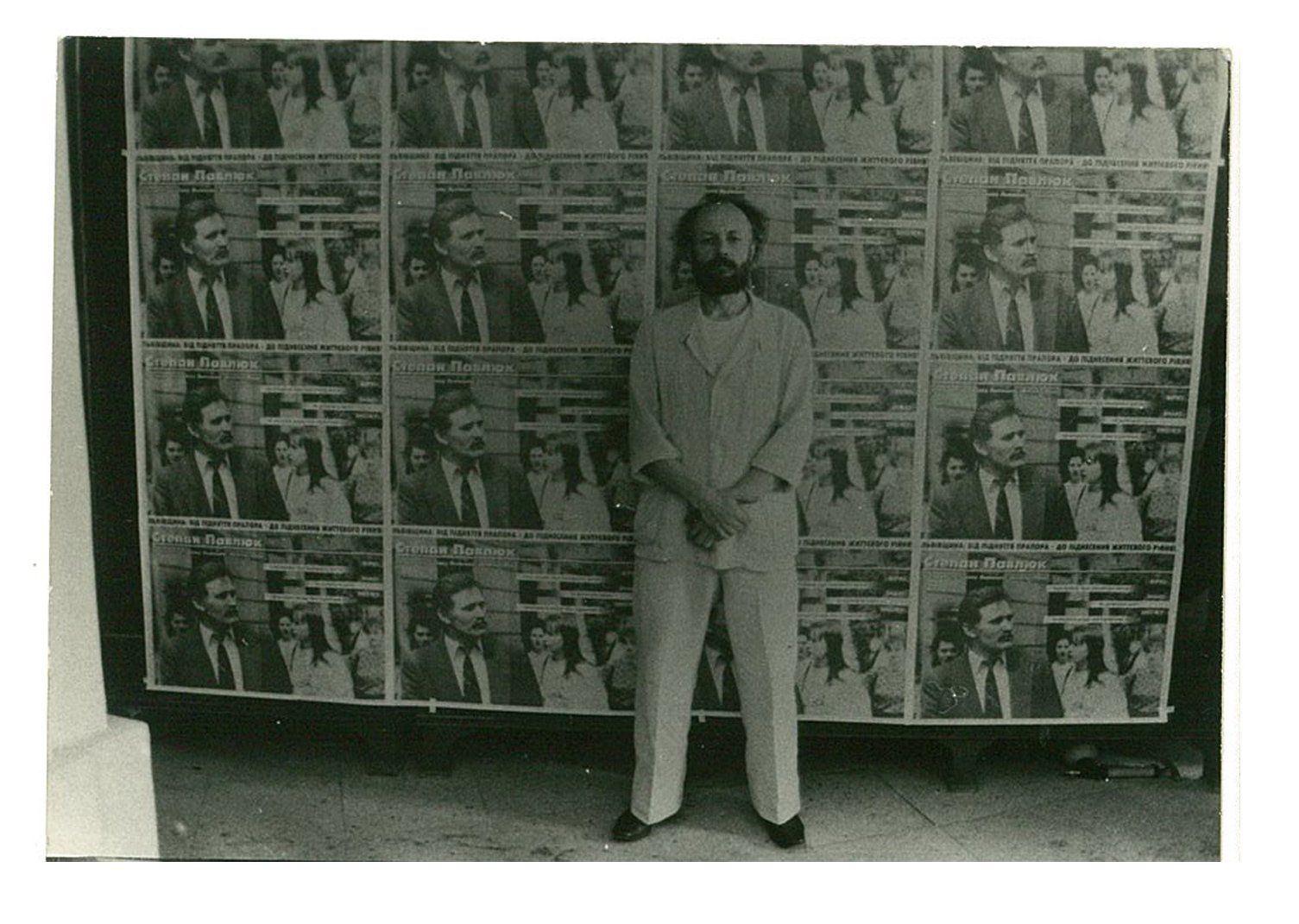

It would be wrong not to mention Lviv here, even briefly, since it will be the key city illustrating the next chapter of the history of informal art shows. Like Kyiv, the first wave of “permitted” exhibitions of non-Soviet art happened under the USSR regime at the end of the 1980s. The initiators were independent artists who secured the support of local bureaucracies and at that time, there was no tradition of apartment exhibitions. Instead, alternative public spaces were formed in cafes or parks. Artist Yuriy Sokolov, then a teacher at the Lviv Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts, was one of the pioneers in independent exhibition-making. He organised Invitation to Discussion (1987), potentially the first group show of alternative art in Lviv, to “allow all artists who cannot break through to the viewer, check their measure, in his own words.”[18] The exhibition was installed in a Greek Catholic Church that functioned as a temporary photography museum during Soviet years. Sokolov also initiated an association under, back then, a challenging title Center of Europe (1987–1990), and independently curated several contemporary art shows at different venues, including Theater of Things or Ecology of Objects in the Dniester Hotel (1988) and, unusually for Lviv, a joint exhibition of Lviv and Moscow conceptualists For the Cultural Recreation! (1991) in another Lenin Museum. Later on, he founded two informal galleries: Decima gallery (1994–95) at central Rynok Square and Chervoni Rury gallery (1995–99) in the cellar, attic, and garden of the apartment house he lived in. Chervoni Rury was not a gallery in the classical meaning but rather a place for meetings, discussions, parties and occasional installations and happenings by Sokolov and his peers.

If to summarise the grassroots cases mentioned above, be they the apartment shows or “anachorets’ gatherings” of the 1960s, squats, or “ruin shows” of the 1990s, we can discover a shared feature. All of them were driven by communities (or individuals who made an effort to be a uniting force behind these communities, today we call them curators) in their need to outline a territory of their own, to establish a place,or to adapt a temporary one for independent exhibiting and, not least important, to simply be together.This drive can be best illustrated by the words of Sokolov in his late recollections of the 1990s: “There were friends, and there were facilities: the apartment itself was a part of my life, all my interests and delights, a place that tightened everything together. Exhibitions were maybe even not the most important part of it all. It was a desire to come and drink together. Not in a gross way, but rather to be together, talk, discuss things, and treat people. My wife was very hospitable! The square meters of my place allowed me to do so. If a man has a capacity, he hosts. It was about tusovka in some sublime sense, tusovka as a separate kind of activity and lifestyle.”[19]

Thickets, Groves, Apartments, and Garages: on informal exhibitions in Ukraine, 1960s—2022: Part II

The broader preliminary research, of which is much presented in this text, was supported by the Sonderförderung Ukraine Hilfe programme by Bundesministerium für Kunst, Kultur, öffentlichen Dienst und Sport. Unfortunately, due to the obvious limitations of publishing texts, we were not able to give enough, or in some cases any attention to many more important initiatives, spaces, projects, and their creators. But there must be no such thing as a full stop in art history. The research goes on and Part III is absolutely in the author’s plans.

Lizaveta German is a PhD in art history, researcher and curator. She is co-founder of The Naked Room gallery (Kyiv) and co-curator of the Ukrainian Pavilion, 59th La Biennale di Venezia. In 2015, together with Olha Balashova she published a book The Art of Ukrainian Sixties (republished in English in 2021). And in 2017 they co-edited Decommunised: Ukrainian Soviet Mosaics book.

This text, published in two parts, is one of four commissioned for Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow, a project implemented by Fundacja Ziemniaki i and Stroboskop Art Space (Warsaw) covering themes related to the production, dissemination, and evolution of contemporary Ukrainian art and culture during active wartime circumstances. Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow is supported by IZOLYATSIA foundation, Trans Europe Halles, and Malý Berlín, and is co-financed by the ZMINA: Rebuilding program, created with the support of the European Union under a dedicated call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced people and the Ukrainian Cultural and Creative Sectors.

[1] Nikita Kadan in conversation with Lizaveta German, 08.04.2024, unpublished

[2] https://asortymentna-kimnata.space/workingroom_residency/

[3] Kateryna Filyuk, The Myth of the “Fence Show”. In The Art of Ukrainian Sixties, edited by Olga Balashova, Lizaveta German, Kyiv: Osnovy, 2021, p. 70–74

[4] Tetiana Basanets, Towards the History of the Unofficial Art of Odesa. In The Art of Ukrainian Sixties, edited by Olga Balashova, Lizaveta German, Kyiv: Osnovy, 2021, p. 64

[5] Yevgheniy Golubovskiy, Apartment Exhibitions of Nonconformists. In Odesa Fine Arts at the Turn of the Century. The Collection of the Museum of Odesa Modern Art. Odesa: Optimum, 2011, p. 16-17

[6] Kateryna Filyuk, The Myth of the “Fence Show”. In The Art of Ukrainian Sixties, edited by Olga Balashova, Lizaveta German, Kyiv: Osnovy, 2021, p. 70–74, p. 74

[7] Oleksandr Roytburd, in conversation with Lizaveta German, 26.01.2015, unpublished.

[8] https://artmargins.com/cultural-contradictions-on-qtusovkaq/

[9] Lizaveta German. Chimera of Intellectual Abstraction. Curatorial projects of Oleksander Roytburd of the 1990s. In Roytburd, edited by Olga Balashova. Kyiv: Osnovy, 2016, p. 36-45.

[10] Mikhail Rashkovetskyi Unnatural / Selection. In Unnatural selection. The first annual exhibition of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art in Odesa. Catalogue. Odesa: CSMS, 1998, p. 16.

[11] Kateryna Stukalova, Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. In Terra Incognita, 1994, No. 1–2, p. 87

[12] Aleksandr Soloviov, Alisa Lozhkina, Point Zero. The Newest History of Ukrainian Art. Part II. Generation at its Zenith. 1990 – mid-1992. Special project of the TOP10 magazine, 2010. http://top10-kiev.livejournal.com/281049.html?thread=894681.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Here I deliberately specify the month of the opening, though the exact date is unknown. Though none of participants pay any specific attention to the fact, this exhibition was put together in a significant period of Ukraine’s statehood formation: right between the issuing of the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine (August 24, 1991) and the referendum for independence (December 1, 1991).

[15] Oleksandr Soloviov, in conversation with Lizaveta German, 11.09.2014. In Yelyzaveta German, Curatorship in Contemporary Art. International Practice and Ukrainian Context. Dissertation, National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture, 2016 (in Ukrainian).

[16] Arsen Savadov, Heorhii Senchenko. Dialogue on Revolutionary Strategies. In Space of the Cultural Revolution: Exhibition Catalogue,1994, p. 2–6.

[17] Ilya Levchenko, Creating a Myth: “Alla Horska. Boryviter” in the Ukrainian House, LB.UA, March 27, 2024, https://lb.ua/culture/2024/03/27/605323_tvoryachi_mif_alla_gorska.html.

[18] Cited from: Bohdan Shumylovych Alternative spaces of Lviv in the 1980s–2000s. In City and renewal. Urban studies. Heinrich Böll Foundation in Ukraine, Kyiv, 2013, p. 76

[19] Yuriy Sokolov, in a conversation with Lizaveta German and Maria Lanko, 14.04.2014, published at http://openarchive.com.ua/eng/sokolov/