Maksym Khodak and Maria Noschenko in conversation.

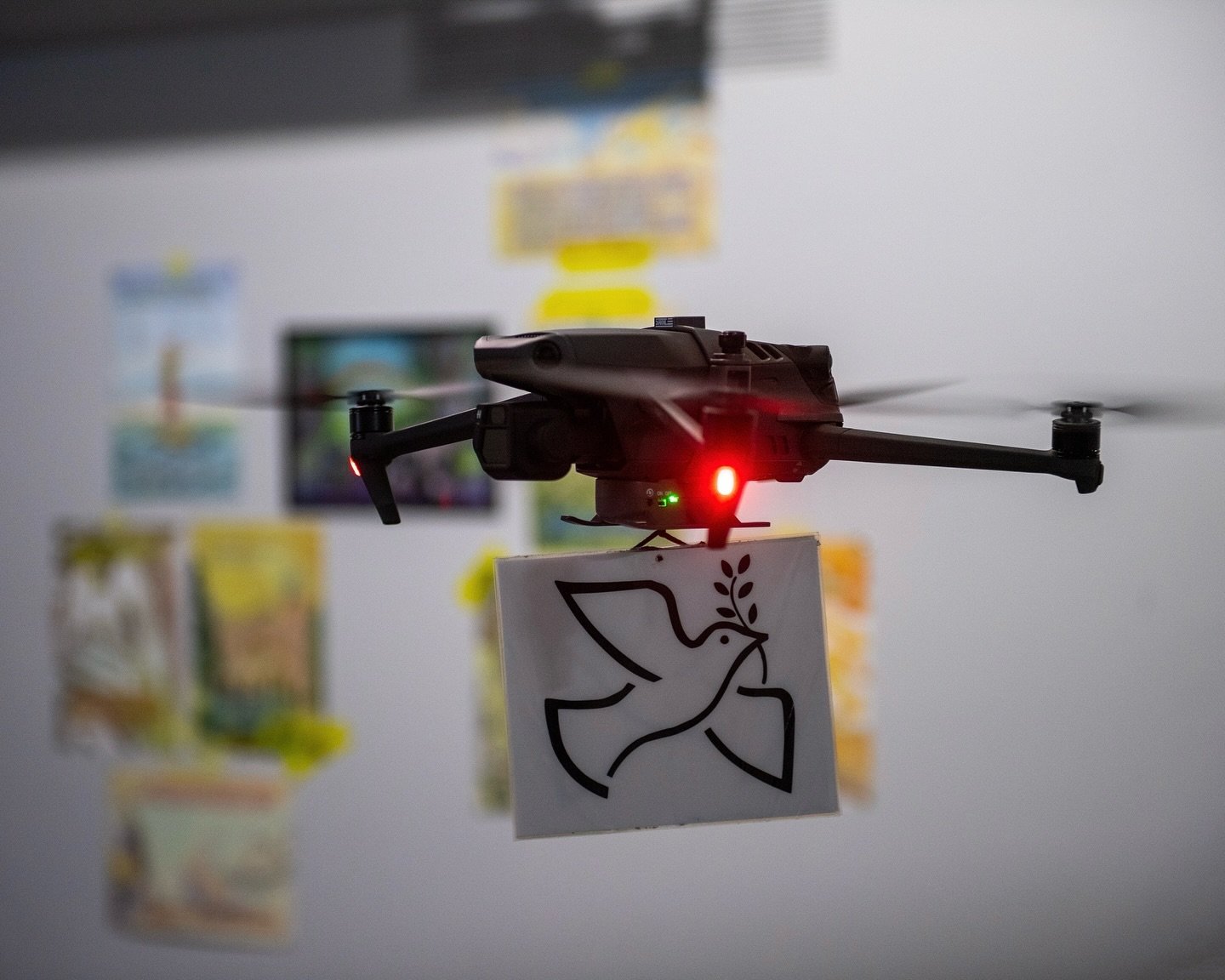

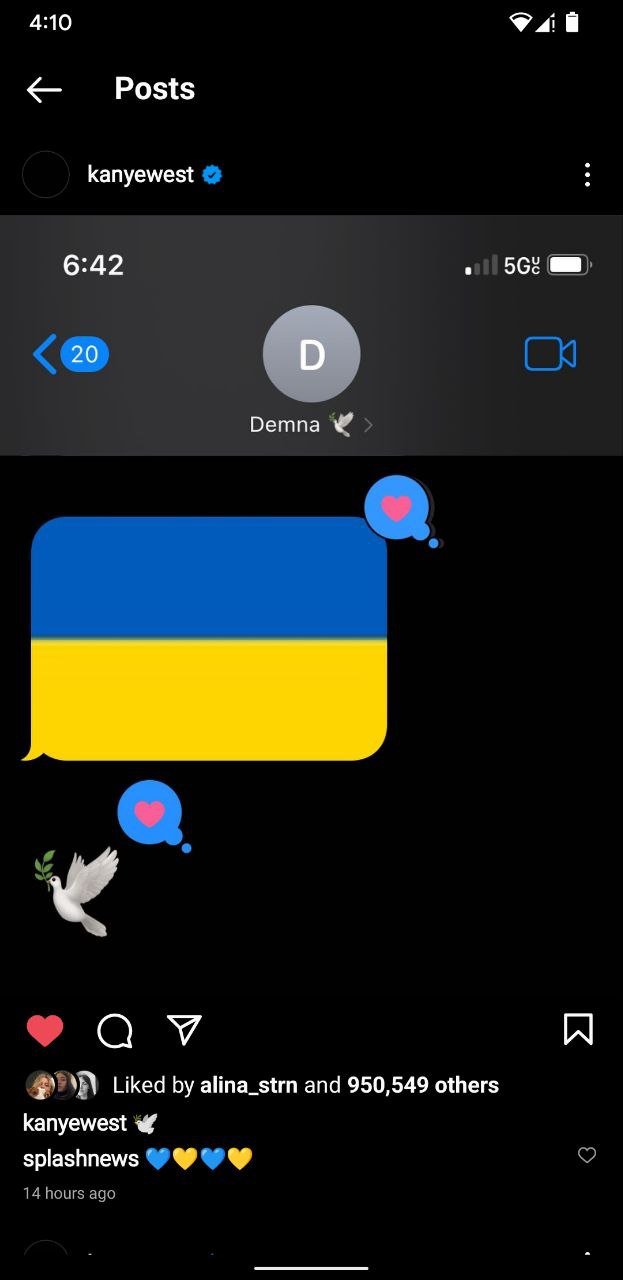

Maria Noschenko: To claim that the peace dove emoji is also a militarized subject might seem like a continuation of the joke. But if we agree that the info war is real, then even its smallest units, those seemingly benign or empty, are real as well. The reversal of the object – the emoji of a dove now carrying a drone – could also work, as a significant number of drones find their way to the front lines through online mobilization and active online appeals. It feels that now we are in a situation of equal exchange of the symbolic and material weight, where the Internet functions as a transit point between receiving images or the latest updates on war and committing to direct actions – whether through donations to fund weapons, clothing, supplies, or through the building and spreading of specific narratives. Yet, the critique of hashtag activism (or emoji activism) is not new. It was also criticized during #BlackLivesMatter, during #PrayforParis, #MeToo, and more. Condemned for its ephemerality, for transforming human suffering into trends, for oversimplification, for commercialization by brands, for its unequal focus on non-Western countries, for, finally, lack of real action. Are these arguments still relevant while talking about the reproduction of the dove of peace/Ukrainian flag/folded hands emojis during the ongoing war? Should we keep the global attention on Ukraine by feeding any form of informational noise around us, or to focus solely on our own narratives? For example, speaking more on how people don’t trust the idea of peace – as peace implies reconciliation, long-term coexistence, and mutual recognition.

Maksym Khodak: It seems to me that users involved in Ukrainian war-related activism were frustrated quite quickly in trying to keep the global spotlight on. Or maybe it’s just that the global spotlight doesn’t light something forever, as it should dance around the world appearing in some random places on a global map. And even my (or our) experience of existing during missile-drone attacks on Kyiv tell me that any informational noise around this attack will not really help me materially. I must think about what kind of active online appeals will make the air-defence over Ukraine stronger? Is it a personal email to my foreign friend? A short message on Twitter with a photo of ruins? Should I post sensitive content in Instagram stories or is it better to send a meme in a Telegram chat? Where will my action be more visible, and what is the main platform to spread these narratives?

MN: I don’t find it practical to define key parameters or building the hierarchy of a more or less powerful platform, as, for example, the total number of users is no longer valid in the case of Twitter, which has become the core platform for volunteers, military, and journalists – a relatively small number of people in reality but with hyperactive productivity. Sorry for being obvious in the next paragraphs, but I find the basic distinguishing between the needs and purposes of platforms is important in continuing the conversation.

The infamous Telegram, a closed type of platform oriented only on communities and the chats that users are subscribed to, became a wartime information boom. It seems like the most uncensored and reactive network, which has created all the conditions for the latest insights through the operation of private networks. Also, Telegram depends less on algorithms. The debate around the soft power of algorithms, which encourages users to delve deeper into previously engaged content and reinforce the user’s interest or point of view, has been actively discussed (primarily around Facebook and Instagram) since 2011. In these cases, the ranking of personal news feeds depends on search history, location, and past engagements (within the platform) which were called “filter bubbles” or constructed and intimate “echo chambers.” The network as a platform was the first principle of Web 2.0 as defined by Tim O’Reilly in 2005.[1] Users stepped out of passive consumption to become co-authors, actively shaping the platform. As a result, the Internet’s role shifted from being a functional information storage to a dynamic exchange medium, creating a new social dimension. A fundamental condition of which became users and their data, that is, permanently adding value to it by the user’s own involvement.

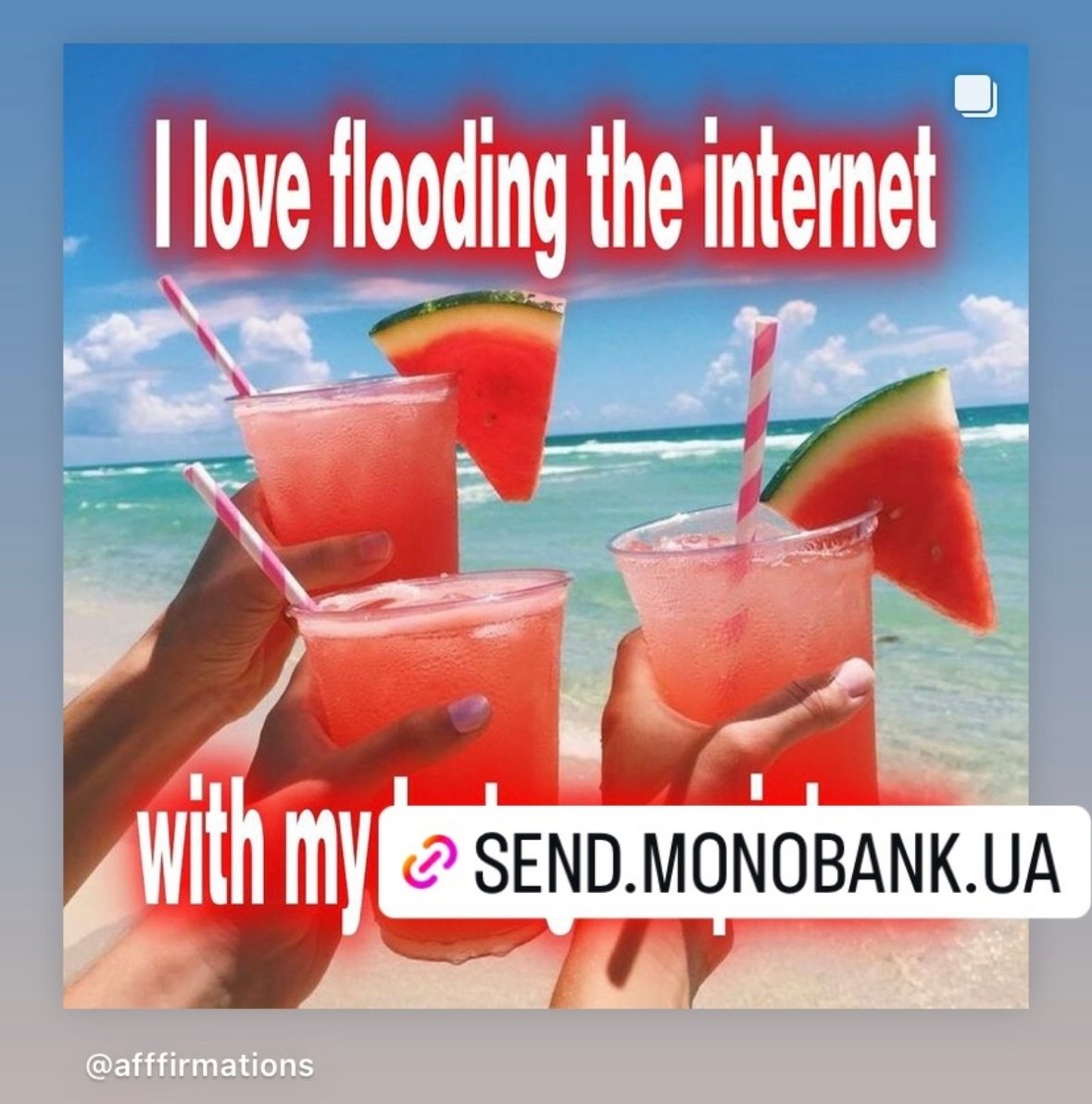

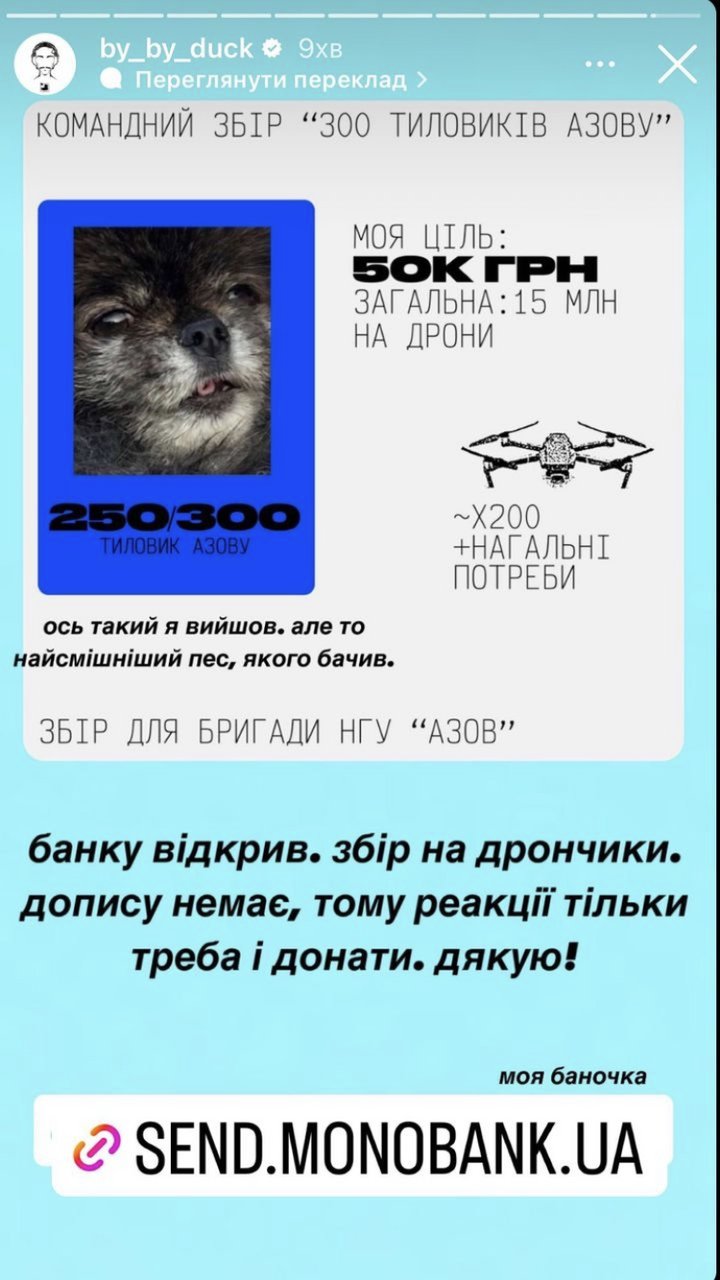

MK: Or we become even more dependent? For me it’s obvious that the foundation of activism in this context is built on the shoulders of corporations or big companies. The success of the volunteer movement was created by the coincidences of updates in the ecosystem of apps in the average Ukrainian phone. For instance, Банка (banka – which is “jar” in Ukrainian) is the most popular tool to collect donations. Банка was created by the banking app monobank and was primarily used for personal savings. But in the latest updates forced by the popularity of collective fundraising, the feature to collect funds together was added. From a useless personal savings app it becomes one of the pop symbols created by the war, helping the army bank while also receiving enormous amounts of new users. Another example can be the simple ability to add an external link to your Instagram stories. I remember some years ago this possibility was available only for people with more than 10k followers. It was the border between the normal user and the starting point of an influencer. It was cool to have a link button. Now every user can do this so the situation becomes more horizontal. I will not diminish the importance of this functionality in the volunteer movement today. Банка and link for Банка posted in stories is two columns that have a stronghold in the Ukrainian donation economy.

MN: The ephemeral Instagram stories gallery is displaying only the most recent events within a 24-hour cycle. Much like the war itself, this space demands immediacy – it is an ever-changing stream of fragmented narratives. A blogger from LA, a call for donations, a death notice, and targeted ads collide, layered within the same fleeting visual frame. This overlay evokes a tension between infantilization, grief, business, etc. This collapse of content generation, where users are expected to produce, consume, and discard with relentless speed and quality, mirroring both the rhythm of war and the position of war victim, who are constantly expected to perform so as not to get muted.

MK: It reminds me a lot of ideas visible in Soviet Montage Theory. The simple act of scrolling through stories is like an attraction montage of Eisenstein, but this time the algorithm is the editor. And in opposition to Eisenstein’s idea, where the impact on the viewer is precisely planned by the director, here it’s given to the logic of the algorithm, which plays with the impact on the viewers and shapes the worlds they exist within. Some cuts between stories work as a Kuleshov effect –“a mental phenomenon by which viewers derive more meaning from the interaction of two sequential shots than from a single shot in isolation.”For example, when a user sees a call for donations after a story about relatives of someone in the war who have been killed, they will be more likely to donate. But what if you see this after a thirst trap or a picture-perfect breakfast?Each person has received their personalised montage. But perhaps it is because of this montage that we continue to donate, as the algorithm keeps us ever engaged. Everyday life frames the need to donate – normalizes it and includes it in a peaceful life. At the end of the day you find the call for donations as same as the need to eat, to post a selfie, to share a weekend with friends. And all of this is directed by the algorithm, which we don’t know and can’t really control. We can use the mute button or view the stories from the accounts directly, not in the queue narrated by the algorithm.

MN: I wonder whether the theory of montage still holds in our present-day world, where the conditions of viewership have radically shifted. Even as we engage with film or television, we are able to disrupt the narrative at will – switching between screens, accelerating playback to 2x speed, consuming multiple streams of content simultaneously. The constant intrusion of notifications from our phones further fractures the experience, dramatically altering our perception of what constitutes a cohesive narrative. Can montage, once a powerful tool for shaping meaning through the juxtaposition of images, still function in an environment where attention is fragmented and the boundaries between media dissolve?

I was also thinking about the dreamy optics of Instagram, often devoid of complex discussions and longreads. Instead, the platform tends to offer ethereal content that creates a surreal, artistic, or aesthetic effect. The design of calls for donations on Instagram follows these standards. Unlike Telegram fundraisers, where a photo of the unit to which the money is being raised is enough, Instagram fundraisers need to be graphically designed as aesthetically pleasing or emotionally captivating. They have to be beautiful and to contain at least one selfie because the platform speaks this visual language.

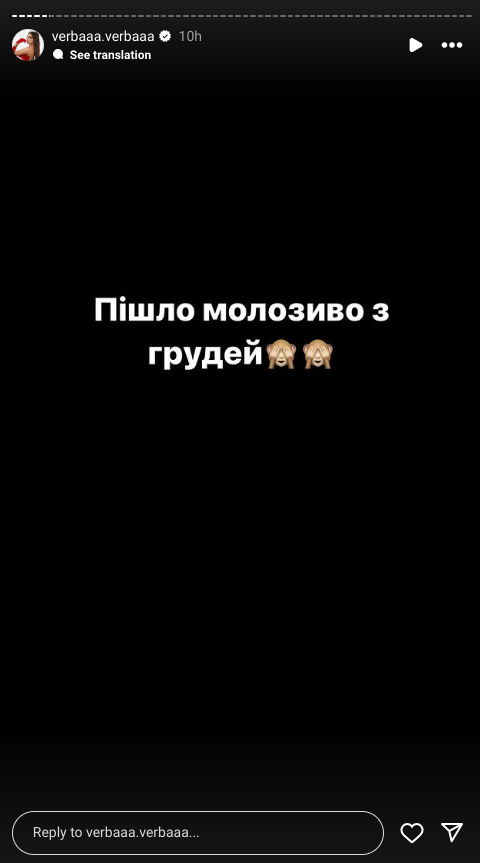

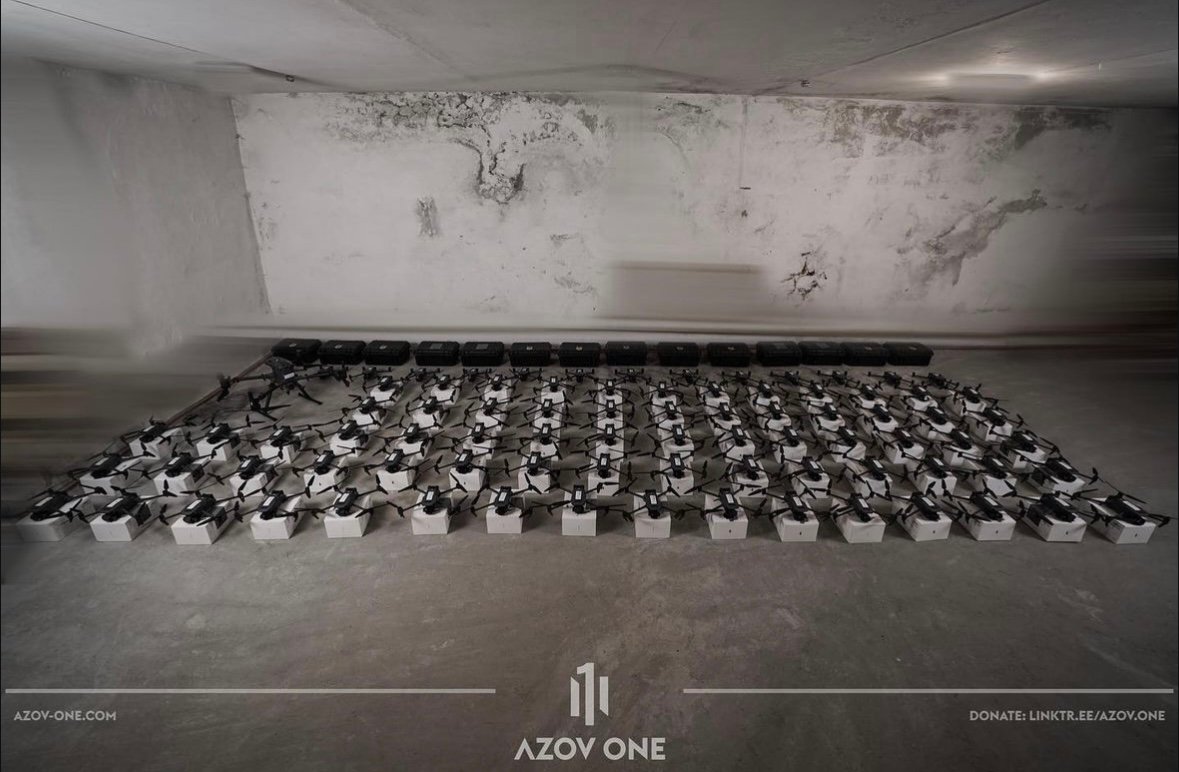

MK: Tylovyky (rearguards) are an interesting, pivotal example of how the spot-on visual identity of fundraising campaigns has created massive success in helping to mobilize new volunteers. The first fundraiser had a goal to collect money for 100 DJI Mavic drones for AZOV. The creators of this campaign are three girls from the creative sphere: Daria Chervona, Maria Romanova, and Alisa Mezhenska. The decision was simple, to divide the final amount between 100 people and involve different bubbles of users to make donations for their friends, with smaller goals. This was to create a more personalised campaign; usually you don’t see the faces behind big campaigns made by big NGOs like Come Back Alive or the Serhiy Prytyla foundation. The term тил (home front) divided the geography of the country into either a relatively calm, peaceful life or a war zone. You saw clearly who is here and who is there. The volunteer initiative provided an opportunity for those outside the front to become local heroes, to make the gap between these two fronts closer. As Daria Chervona said: “I immediately realised that I wanted to give all the participants of this gathering a picture and a caption. The idea of the card came to me by itself. I thought that it would be like a “like” for a person, a mark on their page that says “look, I’m a volunteer.” I thought that through a personalised picture, a person could get social approval and a sense of belonging to the community.”[2]

MN: The success was immediate, so they formed their own “battalion” – 500 people united by the same visuals, a uniform for the people in the rear. Subsequently, a personalized template for an Instagram post (a “rearguard card”) formed the basis of most of the further fundraising campaigns. In addition to the general elements from the template, such as the amount of the overall goal, the amount of the individual contribution and the purpose of the fundraising, a new crucial element was added – a personal portrait, a selfie, or a professionally taken photo. Obviously, acting within the platform, we have to adapt to its rules and censorship. Selfies have always been a favourite of algorithms and an easy way to attract attention in techno-social circumstances.

At the same time, when we find ourselves in a situation of the attention economy, we quite literally convert it into monetary exchange, turning our social capital into political action. Speaking of attention. The phrase “to pay attention” invites broader reflections on the “attention economy”, “attention inflation”, and the underlying currency of this exchange. Petra Löffler provides useful reflections on this topic in Distributed Attention, a Media History of Distraction (2014). Gert Lovink writes about the “like” mechanism as the dominant currency in the attention economy of the web, which took its place as a result of the transition from the link in 2010 and became evidence of a global shift from an open search engine navigation system to a closed, self-referential system. This can be argued with the “data” argument, but in the context of military activism, likes are inferior to the number of donations collected. Yes, everyone is trying to get attention (through organized giveaways, comedy sketches, calls to save lives) in order to convert it into real currency while remaining in the online, mediated exchange situation.

MK: I remember one case when such a process happened literally, not metaphorically. I mean the elections of Lebigovich. Ukrainian Twitch streamer with the nickname Leb1ga – Misha Lebiga – on some of his usual streams, watched and commented on the debate between Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych. During it, fans in the comments section started to create the meme remembered as Lebigovich. It is a play of words with the streamers last name and the last name of the 4th President of Ukraine, Yanukovych. The meme spread widely through the internet, gaining new layers each day, involving the references to other local political memes, like Dobkin “for Yakubovich” etc. The meme evolved into an action that scattered around Ukraine and resulted in the election of Lebigovich. On September 3, 2023 Ukrainian “elections” were held, voting was possible in the form of a donation for the NGO “Come Back Alive” either at the site of the polling station or in the app of monobank. In exchange, you got a “skin” for your monobank credit card or were just able to poke endless fun at election party. In the end, this campaign brought 20 597 035 UAH in donations that was “exchanged” for 588 grenade launchers for the UAF. It also gives a tragicomedic feeling about the simulacra of elections instead of the real ones.

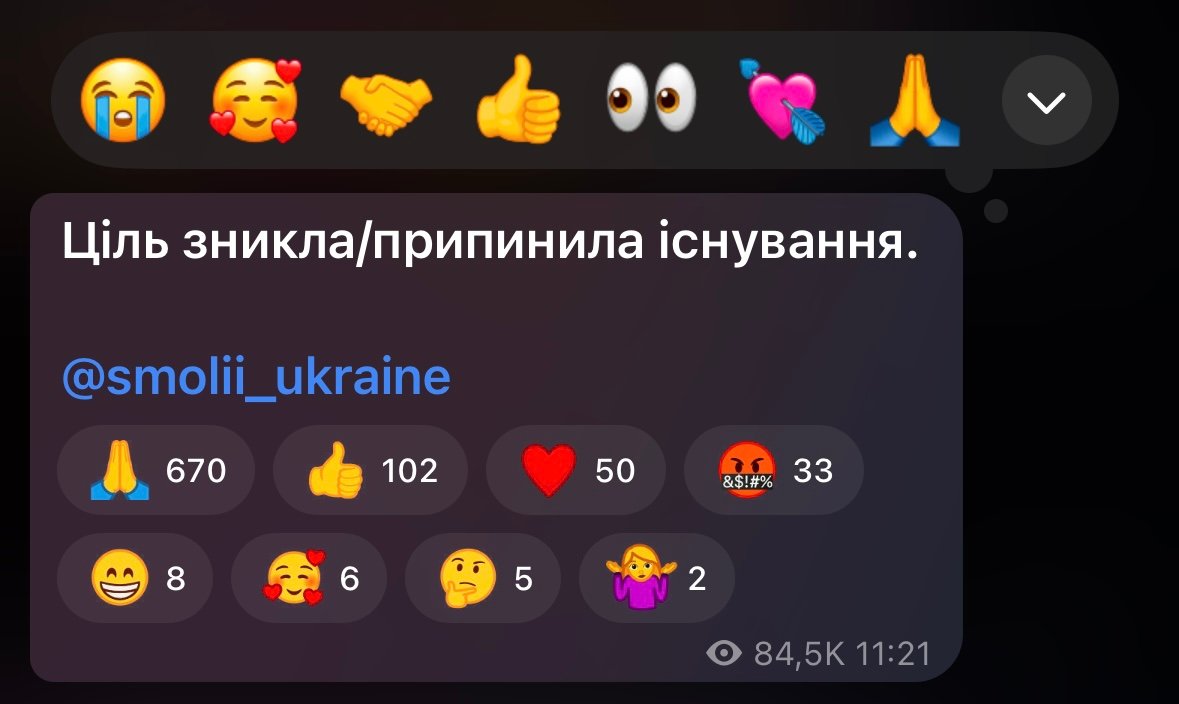

MN: This case is bringing for us an important question about the role of popular

internet activists in the future of Ukraine, after the war. A lot of new public figures have been born on the “informational frontline” by spreading news as fast as possible and giving notifications about targets in the air.

MK: But also, what is the future of our society if everyone is a politically engaged internet activist or can become one in one click? Notification on my phone “the target has ceased to exist”, whatever that means.

Hope this email finds you well,

Maksym

Maksym Khodak (b. 2001, Bila Tserkva) was born and raised in Ukraine and works and studies between Kyiv and Vienna. He studied Contemporary Arts at the Kyiv Academy of Media Arts, now he continues his studies at the University of Applied Arts Vienna (die Angewandte), BA in TransArts. In 2021 he received the Prince Claus Seed Award. Khodak was shortlisted for the PinchukArtCentre Prize in 2022. His films were screened on the 52nd Molodist Film Festival and on the 15th Wiz-Art Short Film Festival. Khodak’s works have been exhibited in the Kyiv Biennial, Mystetskiy Arsenal, Voloshyn Gallery, and PinchukArtCentre, among others. His recent interest is to build a dialogue through art with his generation, people who were born in the 21st century, as an attempt to invent a new political language comprehensible to younger generations.

Maria Noschenko is a researcher and young curator, currently serving as a project manager at ФОРМА and the Pavilion of Culture. Noschenko holds a bachelor’s degree in Cultural Studies from the National University “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.” In her practice, she researches digital humanities, visual culture, and terrorism studies.

This text is one of four commissioned for Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow, a project implemented by Fundacja Ziemniaki i and Stroboskop Art Space (Warsaw) covering themes related to the production, dissemination, and evolution of contemporary Ukrainian art and culture during active wartime circumstances. Under the Lying Stone, Water Does Not Flow is supported by IZOLYATSIA foundation, Trans Europe Halles, and Malý Berlín, and is co-financed by the ZMINA: Rebuilding program, created with the support of the European Union under a dedicated call for proposals to support Ukrainian displaced people and the Ukrainian Cultural and Creative Sectors.

[1] O’Reilly, T. (2005). What Are Web 2.0-Design patterns and business models for the next generation of software?

[2]https://www.village.com.ua/village/city/war/345091-yak-tiloviki-azovu-zapustili-noviy-format-zboriv-interv-yu-z-initsiatorkoyu-dasheyu-chervonoyu