Ant Łakomsk, recipient of the special mention in the Krupa Art Foundation Young Art Prize in conversation with Ewa Borysiewicz.

EB: How are you doing?

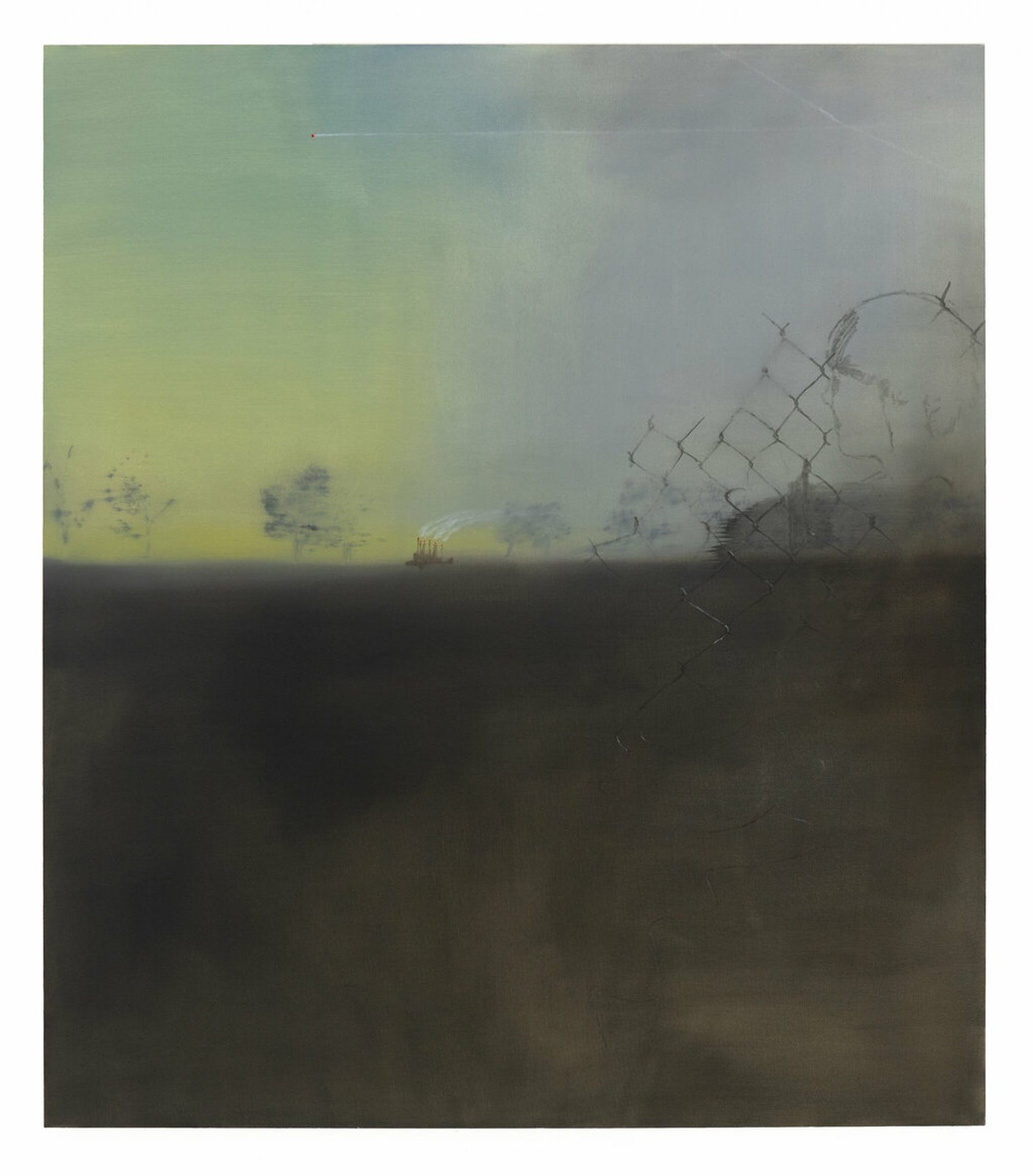

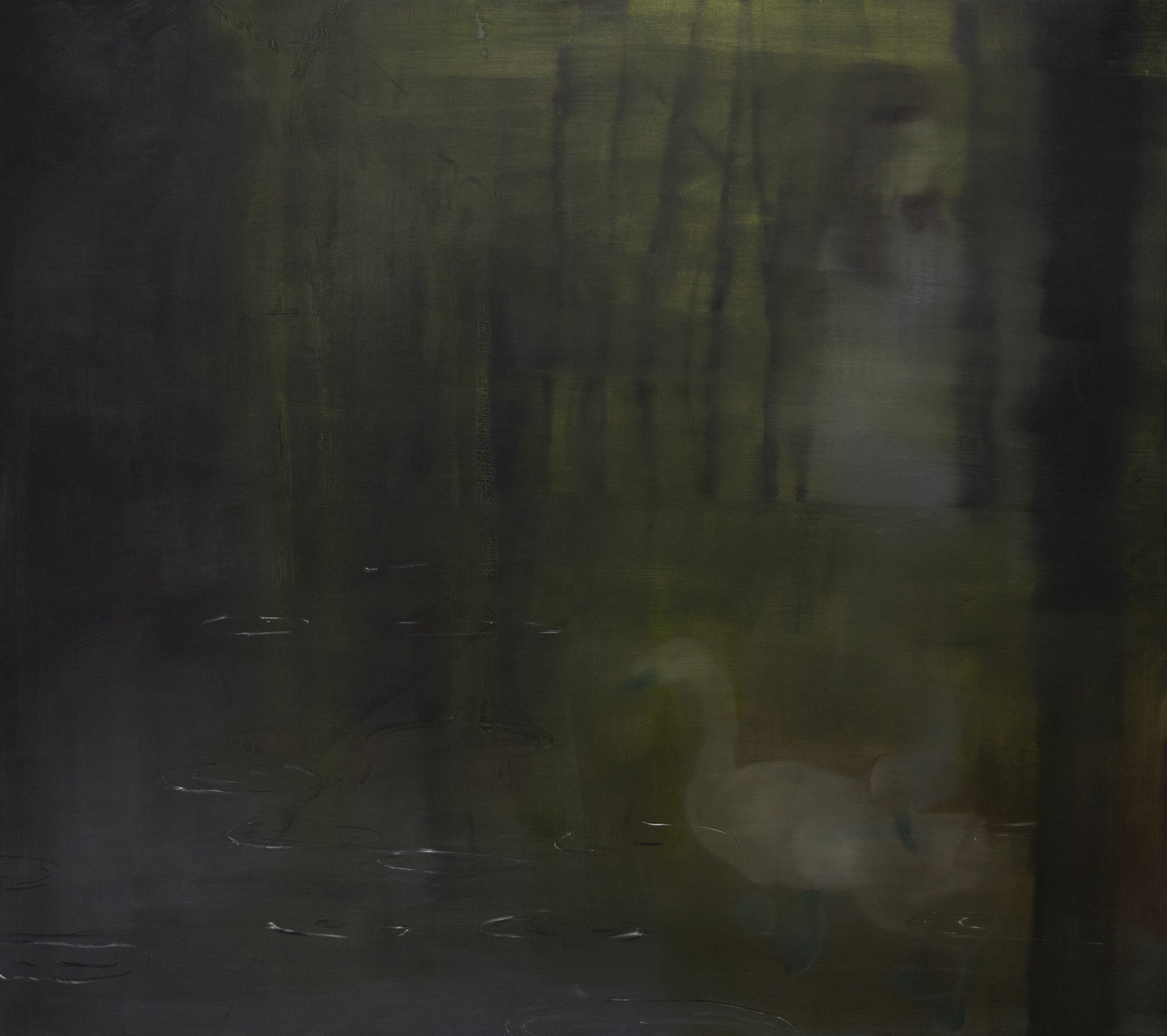

AŁ: I’m having a very intense time right now. There are two important things happening in parallel. One is not mine, but I am very much involved in it, namely the move of Stereo gallery, where I work as an assistant. And the other thing, this time completely mine, are the preparations for the Paris Internationale art fair with Turnus Gallery. It’s going to be a double show – me and Piotr Kowalski – we’re going to present new works, connected by an idea that we worked on together. It seems like subconsciously I wanted to slightly move away from landscape painting; not entirely, since it’s the main subject of my work, but I wanted to try something new.

EB: That sounds like quite a leap, landscape comes up very often in your paintings.

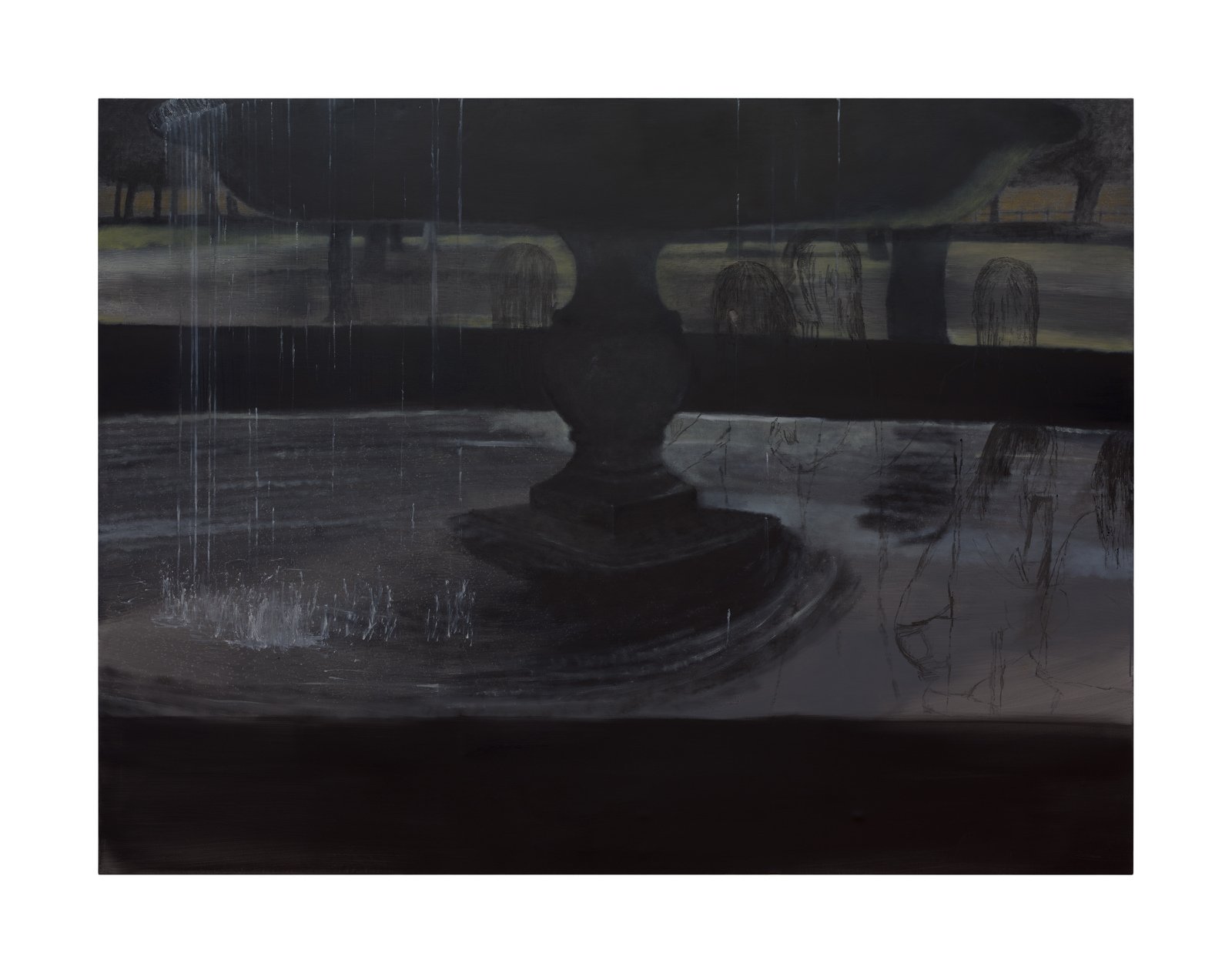

AŁ: I wanted to make the paintings more urban and less sublime. I decided, somewhat willfully, that I would paint pictures of parks. So it’s a gradual shift, a compromise between nature and culture. You could say I’m gentrifying. In all seriousness, I wanted to let my guard down, to turn to things that are most familiar to me. There is a painting by Giacomo Balla called Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash (1912), a study of the movement of a black dachshund. It’s a great painting, like a joke that can’t be told wrong, in the sense that everyone says “Wow! What a great picture!” when they see it. So the parks in my new works coexist with movement transformed into abstract, geometric forms. A bit like Balla, who – as a classically trained painter – made figurative compositions, some of them trivial, but still, he incorporated an analysis of movement into his pastoral scenes. It’s like in his Fontana (1906), where you have an impression that the water is flowing, shimmering, vibrating before your eyes. Balla also drew a series in which he shows a speculative flight of swallows. I say “speculative” because they are not anatomically correct, the birds seem broken, paralyzed.

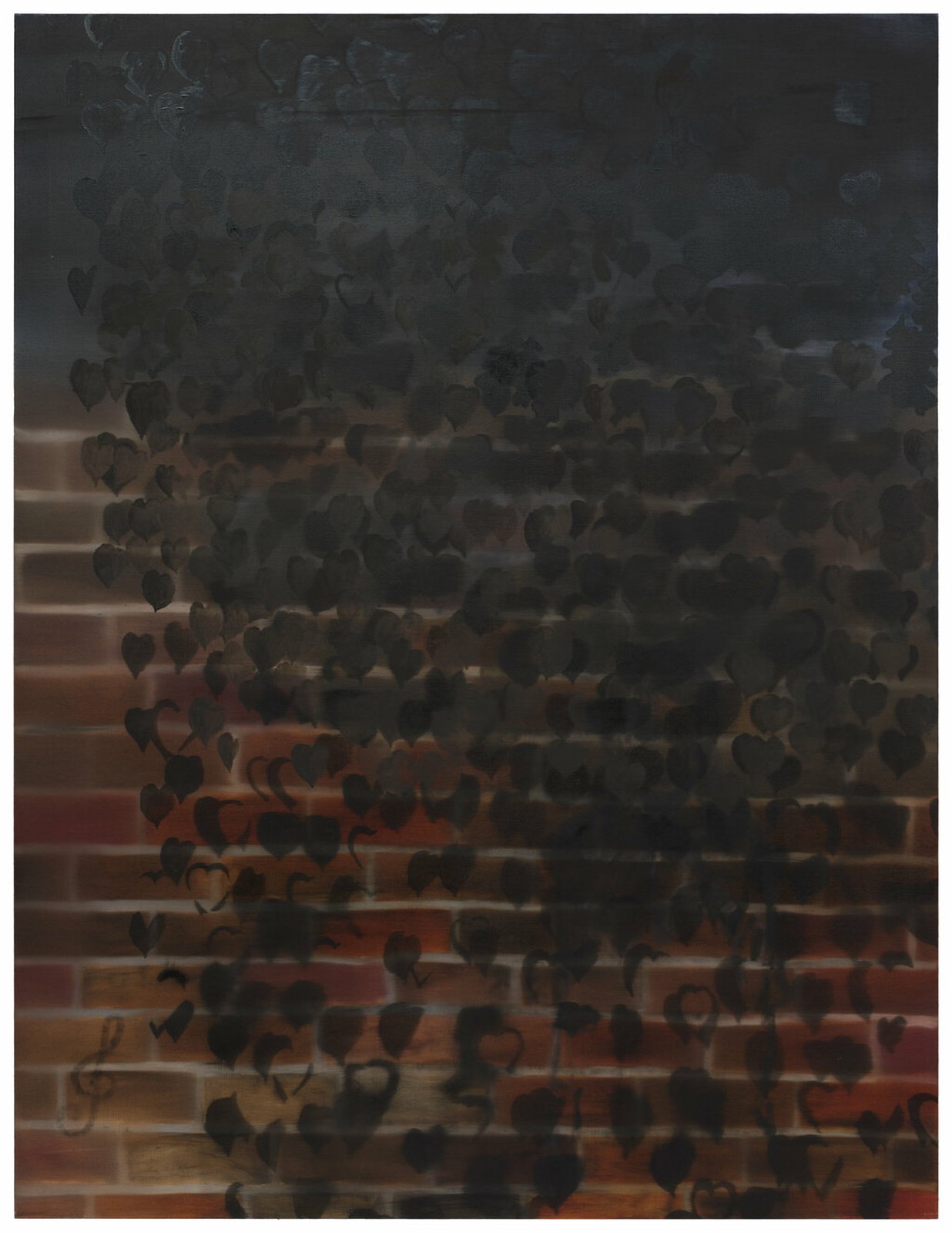

EB: I feel that this is very close to the blurry quality and duplication of motifs often seen in your paintings, like in Wallpaper (2024), where leaves – and contours of leaves – seem to be wandering from the foreground to the background of the painting, and therefore in motion.

AŁ: Yes, and I thought it would be such an interesting direction, creating my own mini-mythology of Giacomo Balla. The result is a series of four paintings, each depicting different scenes, but all coming from the same conceptual framework. I also took the liberty of making a copy of one of the parts of Villa Borghese – Parco dei Daini (1910). I like the idea of such appropriation of the “old masters.” It’s terribly simple, some might say even boorish or unambitious, but somehow, I enjoy copying works that have some kind of art historical import.

EB: There are a lot of such historical references in your painting: Klimt, Bonnard, Turner… You once mentioned to me that painting is such a densely codified medium. That this baggage of iconography, tradition, or technology, is so heavy that it cannot be discarded entirely. Consequently, there is no such thing as complete freedom, the author does not have full control of the painting process. Do you think of your copying of the “old masters” as a kind of gesture of emancipation?

AŁ: It seems to me that striving for complete control in painting will always fail. But appropriating art history is a game rather than a manifesto. I like speculation, wondering “what would happen if…”. On the other hand, sometimes I think I’m obsessed with falling into historical contexts. No matter what I’m painting and no matter how, I never stop wondering what art historical terrain I’m stepping into at each moment. And that’s great. I love it. In general, that’s what’s most interesting to me about painting: it’s a very complicated game. The moment you give it all your attention, it turns out that in your head, there are motifs that overlap, distorting or leveling each other, fighting each other, competing. It may be something that has been with us forever, but it seems to me that it’s now very prolific, and people are very eager to use this mechanism now: to refer to specific motifs, eras, histories, creating “an aesthetic” or “aesthetics” based on this.

EB: Presently all aesthetics are available all at once, no?

AŁ: I think people love aesthetics now, and it’s such a universal and ubiquitous game in art, fashion, and culture in general. And I appreciate this trend immensely and apply it to my art: I like the fact that I can take certain elements, include them in my work combined with elements of my own invention. It’s like inserting false characters into an existing narrative, rewriting a book that you know by heart, or a book required for school. Maybe it’s too literal, but it’s just important for me to generate such private mythologies, twist history, misrepresent it, disregarding the so-called historical “truth.”

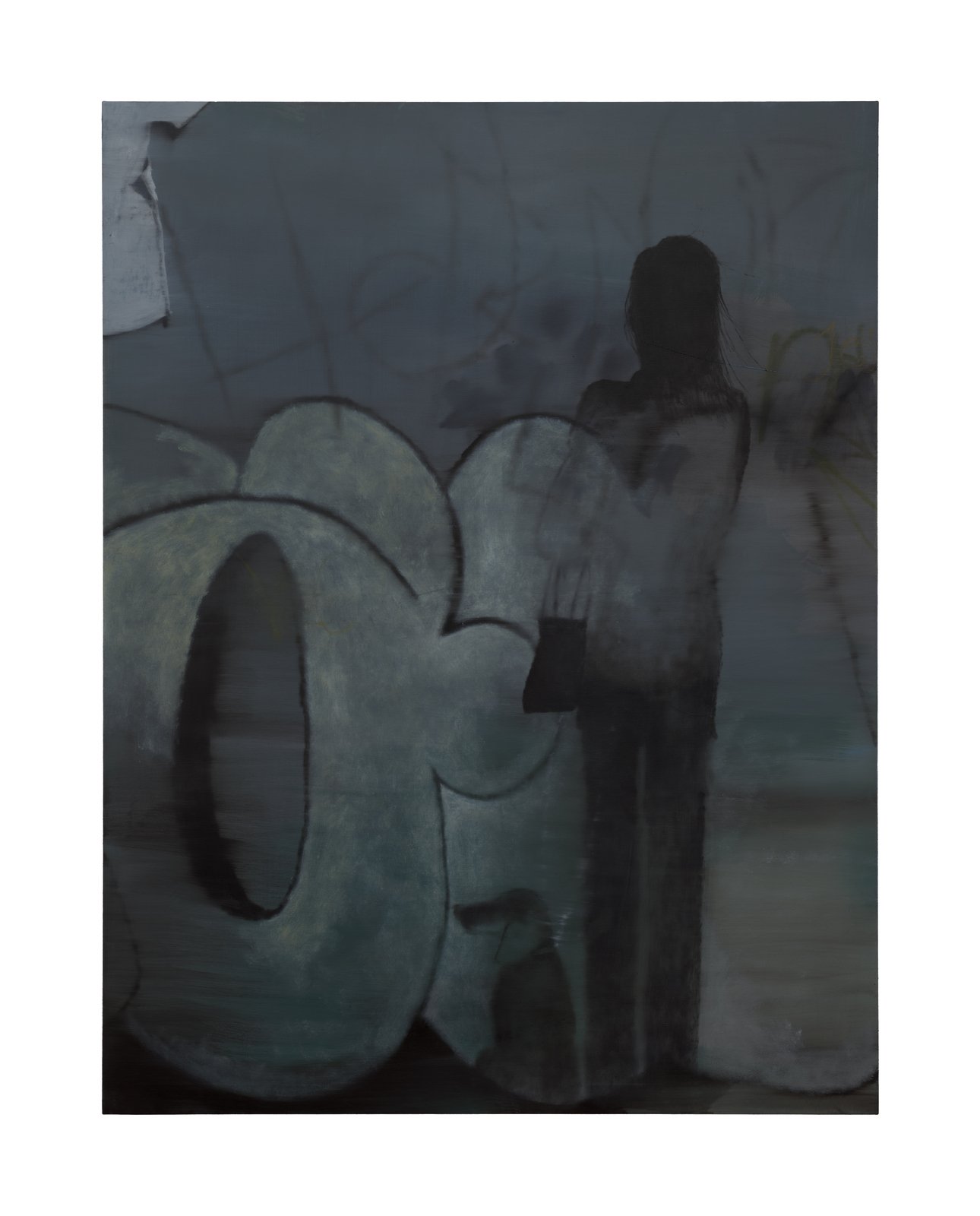

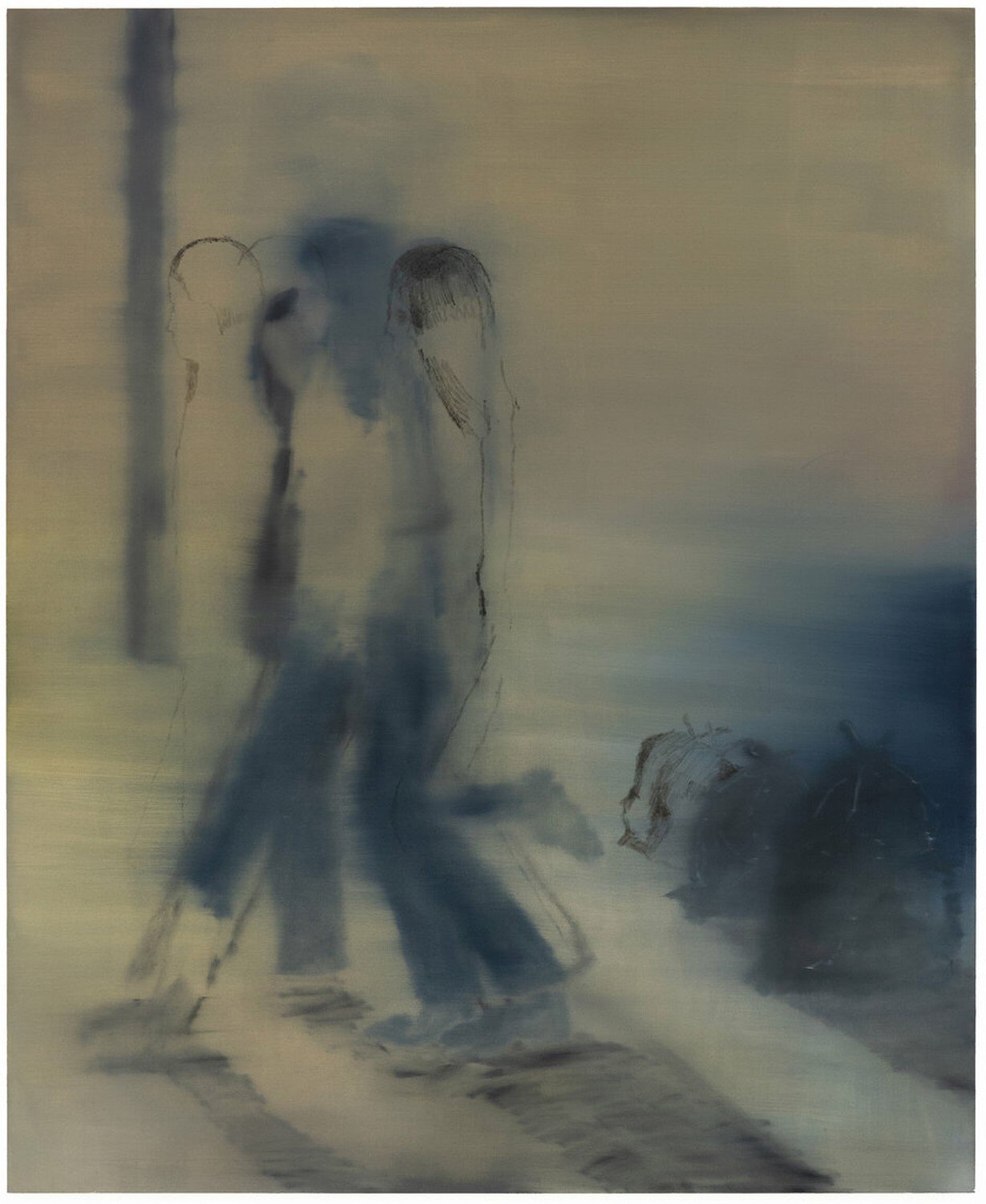

EB: The “false characters” appearing in your paintings are always girls, right? Like the ones in Trash (2024), depicted mid-movement, walking towards the edge of the canvas. Their looks are always based on your own appearance, correct?

AŁ: Yes, I jokingly call them “brunettes.” The most intuitive figure for me in all of this is my own. Painting myself seems most natural. I associate painting someone’s portrait with the desire to control someone, to forcefully decide a person should look one way or another, that it must be figurative, it has to be recognizable, realistic… Self-portraiture is intuitive, natural: you know how your face looks, you see it every day, you know it very well. Nevertheless, I noticed that the figures in my paintings are starting to appear less specific. They seem more universal. They’re “girls.”

EB: You almost always depict them in profile view, disregarding the rules of perspective.

AŁ: Yes, exactly, they don’t cast a shadow either. They interconnect with the background in a way that might seem unnatural or inconsequential. But I don’t care about realism, I also feel that such compositions are more authentic to the work going on in my brain.

Sometimes the “brunettes” are multiplied, they look as if their contours flicker, or move. This effect often appears because of an error in the anatomy of the figure I paint. I repeat the hands, arms, shoulders, heads and these different versions overlap. Sometimes I remove the mistakes, but not always. Suddenly one character becomes five, or turns into their own afterimage, or has four hands. It’s like having something in the back of your head, trying to remember it very hard.

EB: I remember you saying that you decide on the compositions spontaneously, and even though you research art history thoroughly before you start working, you still work intuitively. You don’t make preparatory sketches. I wonder what is in your mind when you confront a blank canvas? Where do you start?

AŁ: I don’t prepare for it at all. I’ve just now also realized that paradoxically this is a part of the preparation. I certainly think about paintings a lot, but I never succeeded in finishing a painting exactly how I imagined it in my head. I also don’t believe that it’s entirely possible to do that, to have full control of what you paint, your imagination, your heart or soul. For me the painting has to materialize by itself, so to say, through intuition. And I find a great deal of pleasure in it, also a great deal of sadness and frustration. Still I realized that I have to be totally resilient and have that patience, because maybe in the next second a thing happens that rewards this whole ordeal. And when suddenly it occurs, it’s very rewarding. But as for control over the process… it’s an exaggeration to say that I “finish” the paintings. Rarely do I have such 100% certainty that the painting is finished. The motifs from the paintings tend to reemerge in my next work. In the sense that I feel, even though these paintings may differ, they are still all practically about the same thing.

I think I got very attached to the uncertainty of this process, the gap between expectations and reality. Such intuitive painting, without blueprints or sketches, makes you very humble and vulnerable. I greatly appreciate all my artist friends who prepare meticulously. But personally, I have somehow always felt such a need to let go. And I am well aware that the final shape of a particular work of mine is not entirely my idea: my thinking is automated by tradition, historical references, and my skills.

EB: And when you say that your paintings are about the same thing all the time, what do you mean?

AŁ: What I tried to say is that these things that I paint belong to the same place, they are all parts of the same world. I would never say that they are realistic, rather they show my version of reality, a version distorted by memories and experiences. Like an alternate reality, where things happen differently. But still in a familiar way. A reality in which it suddenly turns out that there is a narrator, that there are some mechanics to it all.

That’s why I like repainting the “old masters”:I can take someone else’s reality and twist it into my own, distort it. I can win a place for myself in these displaced narratives, snatch a piece of them for myself.

EB: In addition to art history, your paintings are based on dreams and memories and all of them carry the same epistemological weight in your paintings.

AŁ: What fascinates me about the works of “great” painters is that they are so distant, unattainable, functioning only as a certain image, a misrepresentation. Surely, over time, the control of the work and its interpretation fades away, the motifs break away from their prototypes and become autonomous. Despite the long research, I will never have access to the full context and complexity of an artwork, the historical facts will merge biases and beliefs, nevertheless. I will never have the full picture of the artists’ motivations, their circumstances, how it felt to create a work like this in a concrete socio-political context of the past. And I don’t really care either, in the sense that it just seems to me that that’s where all the magic of it – or maybe perversity – is that you don’t have to feel like you’re taking responsibility for things that have already happened.

EB: This connects to what you said about aesthetics and how the past gets reduced to an image.

AŁ: We also sort of live in a time where one expresses oneself through an aesthetic, there’s also a care to follow it consistently, so that it seems structured. But this too, I think, will change and organically morph into something else. There’s this tendency or stereotype, that trends always come back after 30 years. I noticed that this time distance gets shorter and shorter these days: it’s no longer 30 years, it’s not even a decade at times, the echoes are getting faster and faster. I’m curious to see what happens once we echo things that happened a year ago, 5 months ago, a month ago. Perhaps we will start to echo the future. I am secretly hoping for such a breakthrough moment…

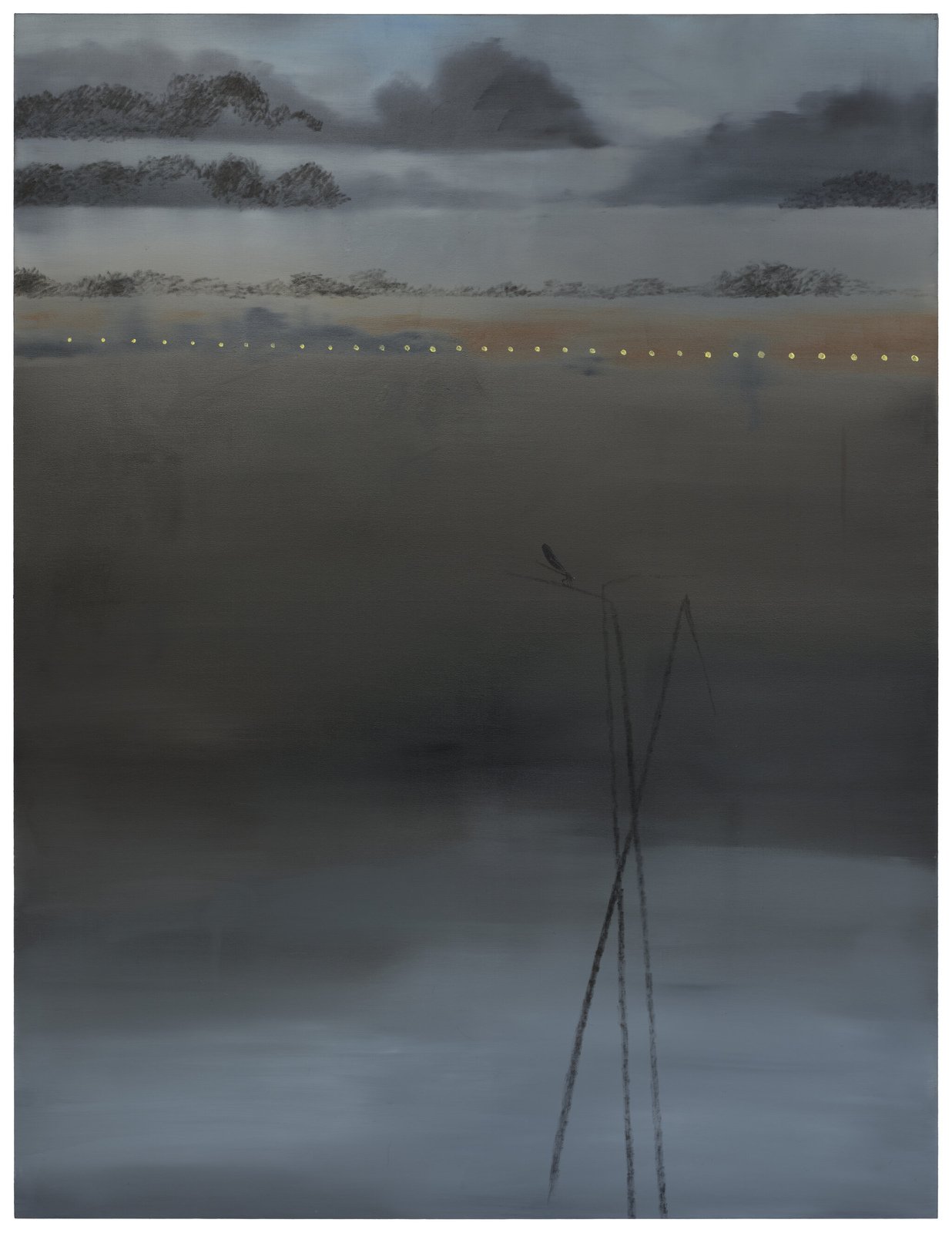

EB: Coming back to your painting. You paint with oil on canvas but in a very specific way, the end result resembling watercolor. I very much associate this effect with the “place” from which the painting emerges, i.e. from the undefined space of a dream, a memory, where things overflow, merge or morph with each other.

AŁ: I’m glad you mentioned watercolors, it was the first painting method I took on. It’s probably the most difficult technique. Oil paint is very flexible, and they allow you to work on a painting for longer periods of time. Watercolors do not tolerate inconsistency, hesitation, or lack of regularity. They will always dry very fast. Mistakes are unforgivable. But even though I switched to oil paint, this seems consistent in the sense that it leaves room for the agency of a subject other than me. Giving some part of the causality or even inventing a sort of subjectivity to the painting.

I would probably never say that the painting has a life of its own, but I like to invent an awareness of the image and treat it as a tool, a permanent part of the process. You never know what the painting will look like at the end. In the case of watercolors: when they dry, they change colors completely. Suddenly you find that the pigments totally mix differently. Some stay on the surface, some soak into the paper very much. I also always used a lot of water, to the point where I would put these papers in the bathtub and paint on large formats just some, either characters of myself from my head, or scenes that I remembered, or, or some that sat in my head somehow, and at some point I switched to canvas and thus started painting in oils. It was such a very organic thing. Maybe it was also a matter of me wanting to see what it’s actually like to have a little bit more of that control in the sense that I’m still looking further for that compromise, to pull that line a little bit more to my side.

It’s intimidating to learn to paint with tools that will never allow for control. It’s hard to learn to drive a car when your brakes don’t fully work and oil paints are like a car with automatic transmission. Even so, I try to leave some decisions to the matter itself. Or, I don’t know what else to call it: the subjectivity of the painting. I still paint with very diluted turpentine paints, at least in the first stages. At the very beginning it was also super intuitive. I was never taught oil painting by anyone. Even though my mother is a painter, there was no point in my life where she could pass on that part of her knowledge to me. Nor was there ever a need for it. And also it seemed to me that maybe in the long run it would give some more interesting results. And in a way it did. Somehow I am never able to put myself sort of above what I paint: it becomes separate, co-created, not fully mine. I don’t know how else to say it. That these are things that fall out of my hands very quickly and very easily. But I see some great value in it.

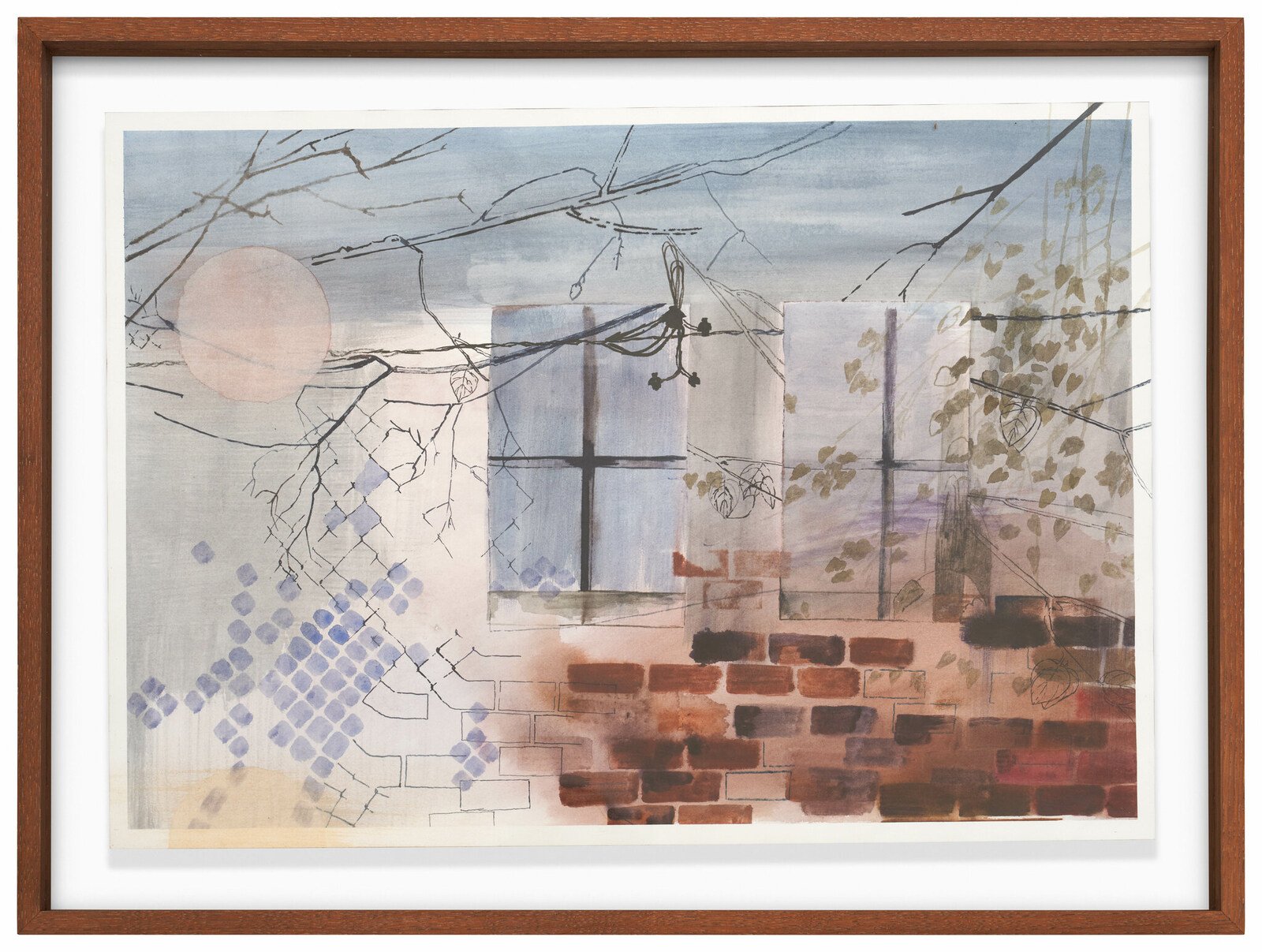

EB: I also find it very interesting that you don’t differentiate between foreground and background in your painting. The two intermingle, spill into one another. There is a painting called Clock from 2023 and it shows this phenomenon well.

AŁ: This is one of the few paintings where I was in control of the composition. I came up with an internal logic for the work and tried to follow it carefully. The central motif of the painting is the clock and surrounding it, I placed objects – branches, cables, leaves, mosaic tiles – as if they were hours. One motif emerges and then morphs into another one, marking the passage of time: one becomes two, two becomes three etc. The painting has a rhythm: the branches transform into cables, cables overlap with bricks, then the mosaic tiles and so on.

EB: Clock beautifully shows the repetitiveness of some days and the almost imperceptible, yet definite, flow of time. Both – repetition and metamorphosis – are key features in your work. Like in Single petals of the same flower (2024), a painting where a wall of bricks transitions seamlessly into a sheet of lined notebook paper.

AŁ: This repetitiveness is related to the constant attempt to measure myself with simple, even clichéd themes. And with metamorphosis I test their potential to accommodate various perspectives and interpretations. Sometimes I repeat certain elements, one to one, and wonder how they will perform in a different context. It’s also connected to my intuitive painting method: these motifs, repeated over and over again, are just an excuse to start, they act as a door through which I can enter the painting realm so to say. It’s a very strange kind of automatism. I think of the paintings as something that will outlive me and I try not to get greedy when it comes to the variety of things that I paint. I try to control my cravings. I understand metaphor as the interpretive potential of a given painting motif. This is interesting to me: regardless of what I decide to use, it will always mean more than just itself in the eyes of the viewer. Nothing is ever what it seems at first glance. This is very perverse: I decide to paint a wall, and someone viewing it will always have some idea of why I did it. Exactly like me when I use the paintings of the “masters.”

EB: I feel there’s a lot of interpretive possibilities in your work, perhaps precisely because of your focus on a fixed set of elements. They don’t tell – unlike the surrealist painting that is very popular these days – an individual story of the author in a very evocative, narrative way. I have the impression that in your works, your subjectivity does not play such a dominant role: in addition to your own voice, others resound on the canvas: the material, the story, the collective subconscious.

AŁ: It means a lot to me that you say that. Somehow it seems to me that painting in general is much more interesting than any individual story. I have the impression that such strongly subjective storytelling is like retelling a dream to somebody. Well, it doesn’t lead to anything, and at the end of the day you catch yourself thinking that you actually know how the story is going to end before it ends. No matter how individual the stories are, they’re always going to fall into some patterns, schemes that are just familiar. I don’t know where this is supposed to lead. I know the song already, and the fact that you sing it a little worse or better doesn’t change anything. I’ve always been attracted to the potential that the medium itself carries. Working in art and especially in something like painting, you get lexicons, dictionaries, instructions, and for me using them is much more interesting than inventing new words, concepts, terms. In the sense that it will turn out anyway that the “word” you are inventing was already there. When I learn that something has already been experienced five or more times, I am not disappointed. It even gives me some confidence. I think that reinventing the wheel is totally unnecessary: maneuvering between conventions is more interesting, drawing from history, manipulating iconographic motifs, combining styles can even emphasize your individual perspective more than talking about yourself explicitly. Searching for intermediate forms in phenomena that at first glance exclude each other, I associate this with finding a place for oneself in the world, it paradoxically gives more in terms of self-expression.

BIO

In her practice Ant Łakomsk uses painting, sculpture and installation. She is interested in clichés, metaphorics, its simplifications and wry translations. Using a simple visual language, she refers to intuitive, banal and non-rational emotions. Graduate of Dr. Wojciech Bąkowski’s Poetics Studio at the Faculty of Media Art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Finalist of the 46th Biennale of Painting Bielska Jesień and Young Art Prize (2024), Krupa Art Foundation, Wrocław. Lives and works in Warsaw. Łakomsk has received a special mention in the Krupa Art Foundation Young Art Prize and will present a solo exhibition at the Foundation’s gallery space in Wrocław in 2025.

Artist: Ant Łakomsk

Special thanks: Krupa Art Foundation

Photos: All images courtesy of the Artist and Turnus Gallery, Warsaw.