Anna Smolak in conversation with Jussi Koitela on trust and measures in curating

This conversation took place in Riga on the occasion of the opening of the 15th edition of the contemporary art festival Survival Kit, organized by the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art. The festival, which emerged in response to the economic crisis in 2009, has become an internationally recognized event, critically engaging with urban narratives. Titled Measures, the exhibition, curated by Jussi Koitela, spans both sides of the Daugava River, bringing the city’s situated knowledge to the surface.

Anna Smolak: I wasn’t sure what to expect from an exhibition titled Measures – the word can encompass so many different meanings. I was surprised to see it tackle such fundamental yet elusive concepts as trust, truth, and time. It felt as though, amidst today’s chaos, redefining or reinterpreting these concepts has become more relevant than ever. But let’s start at the end. In the final pages of the handbook for the exhibition, you state in the note: don’t trust – don’t trust the exhibition, the curators, or the institution, as they all have their own agendas. However, you suggest that maybe art is something we can still trust. A provocation, an insider’s observation, or a curatorial strategy?

Jussi Koitela: Maybe it’s more of a strategy. In many of my projects, I aim to bring a sense of criticality, or even self-criticality, to the curatorial process. This is a form of institutional critique that I believe should be inherent in both curating and artistic research. I hope to work in a process-oriented way, even within one longer project. I keep the ideas and claims of the project evolving and adapting over time. People often treat these critiques or contradictions as fixed positions – statements that remain unchanged. With this final note in the publication, I wanted to introduce more flexibility, almost like a learning tool or guide for the audience as they navigate the exhibition. By questioning the idea of trust, I hope to encourage them to engage with the contradictions present in the works and in the exhibition.

I often think about situated knowledge as one of the biggest challenges of an exhibition and of art institutions. On one hand, situated knowledge comes from marginalized or oppressed communities and bodies, since privileged groups often do not recognize that they are situated and tend to feel that reality is universal. But once situated knowledge enters the discussion, it can lead to polarization, creating a sense that there’s no room for shared experiences, or maybe there has never been shared experiences, even if there seems to be still need and longing for those. When we attempt to make invisible knowledge visible, we challenge the idea of a common, shared space. I find exhibitions and artistic programming a really meaningful place to explore this tension.

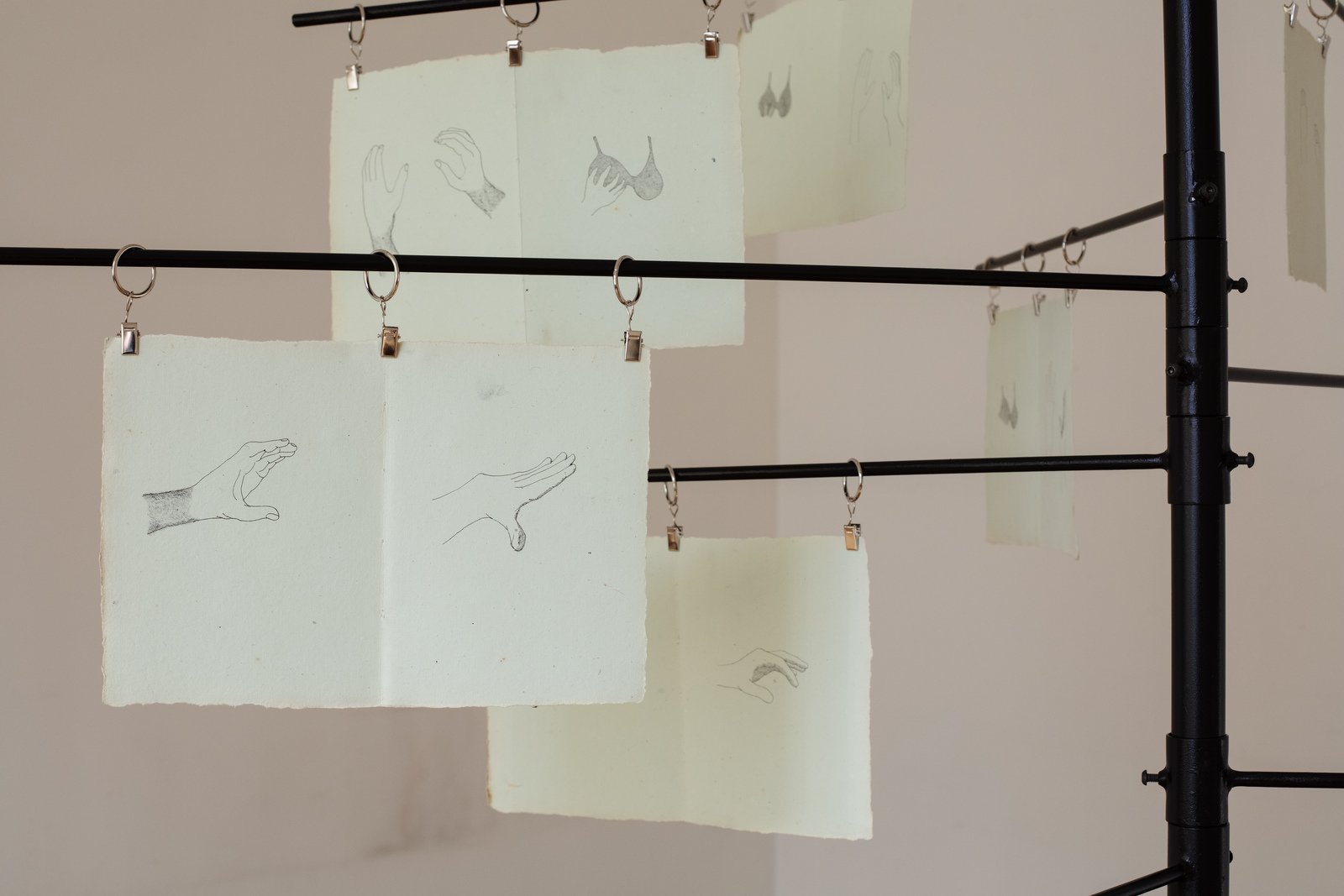

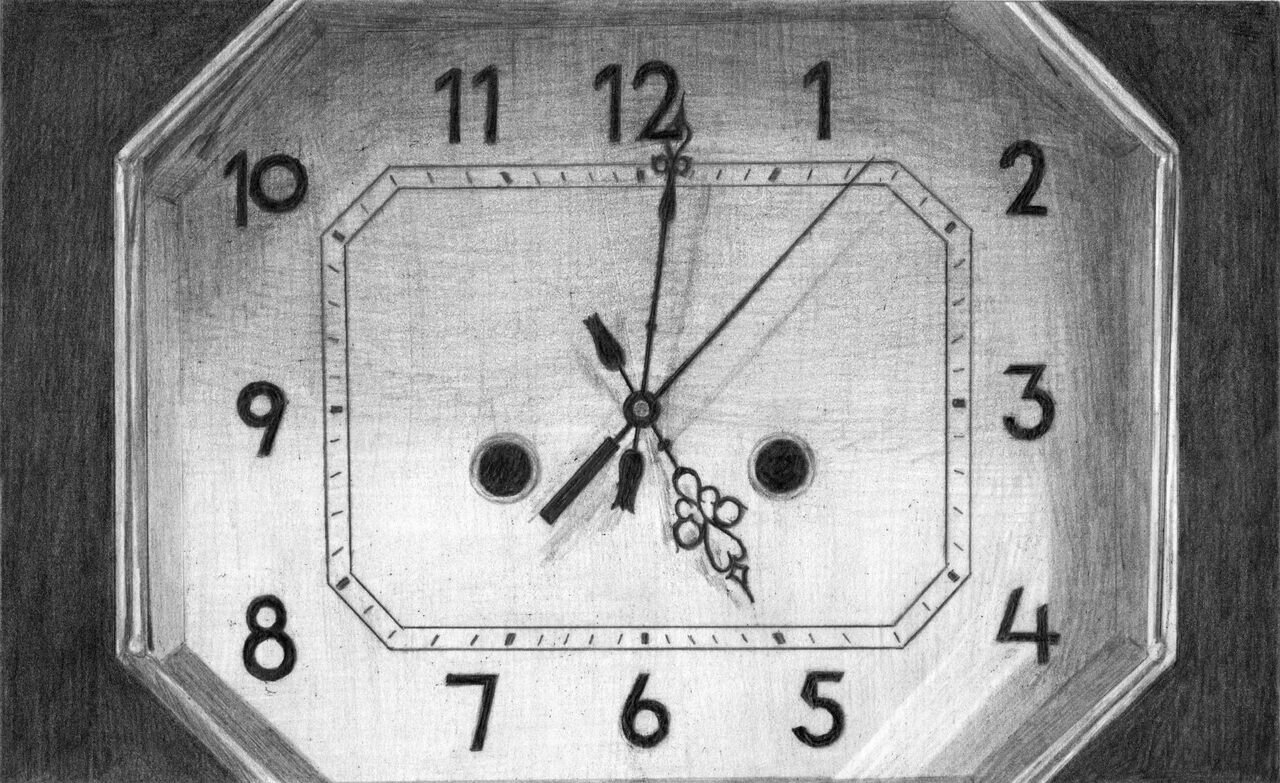

AS: At Amatu Iela 4 [Craft street] we are guided through the exhibition rooms by small arrows on the floor; they are curly and somewhat disorienting. The work by Luīze Rukšāne, Clock, Clock on the Wall Tell Me, What Hour Is Suited for Nothing, is a series of clock drawings. They all show the same time, but time seems to pass differently for everyone. Līga Spunde’s fictional character speculates on the future of Riga, while Fabien Giraud and Raphaël Siboni take us back to the early 19th-century workers’ revolts in Lyon with their dystopian vision. The exhibition treats time in a non-linear way, pulling the viewer into different temporal realities. It’s hard to escape the omnipresent uncertainty of time – you’re drawn into a spiral of it.

JK: Interestingly, time wasn’t initially a key focus of the show, but it emerged through the research and collaboration with the artists. As we worked together, I realized that many of the artists’ proposals engage with the concept of time or create different durations within the exhibition. This was especially true with some of the Latvian artists, who were more familiar with the local context and had more resources to work site-specifically, including time.

Luīze’s work and its focus on time in relation to the city really opened up this concept for me. As we developed the show, I started to reflect on how standardized time is, how it’s presented and measured, and how that can contrast with a more performative or fluid understanding of time. It made me question how we measure and organize time and duration, which in turn shapes our relationship with the world.

A lot of the works explore this in different ways but they all touch on broader philosophical questions. For instance, who or what is present when meaning is created, or knowledge is formed? What kind of struggle is knowledge formation in the city? I’ve also been influenced by various readings that aren’t directly referenced in the exhibition, such as Bruno Latour’s earlier works on science and feminist philosopher of science. Susan Leigh Star, also referenced by Donna Haraway, who has worked extensively on categorisation and standardisation in science.

AS: The building on Amatu Street, now the main venue for the exhibition, has served various functions over the years, including as a guild shop, Soviet and Wehrmacht counter-intelligence agencies, and more recently as the Riga Support Center for Ukrainian Residents. These shifting roles and hidden agendas reflect how truth is constructed, concealed, and revealed across different periods and contexts. How do you view our responsibility as cultural practitioners toward truth today?

JK: It feels like the concept of truth, or even facts, has somewhat lost its weight in the artistic context. Of course, there are exceptions, like Forensic Architecture and other research-driven practices that operate in a space between art and investigative journalism. I considered incorporating journalism into the exhibition, but that proved difficult. However, I was in touch with investigative journalists from Latvia and Riga from the early stage of working on the exhibition.

The concept of journalism, as we know it today, was virtually non-existent in the Baltic context during the Soviet era. This made me reflect on my own experiences growing up in Finland. Although Finland was in some ways part of the Eastern European sphere, we still had the notion of free media, even if certain topics weren’t openly discussed. However, I was told that in Latvia, people often trusted rumors from their neighbors more than any official news source. This lack of a basic, profoundly shared truth shaped their perception of reality.

I sometimes feel that in the art world, by focusing on speculative futures or situated knowledge, we do something similar. Art can often feel like a form of “gossip” – we pick up narratives that are lost or overlooked, but there’s no built-in accountability for how those narratives are picked up or used. I think that’s incredibly creative, but it also raises important questions. What interests me is how an exhibition can create its own systems of accountability. Not by imitating journalism, academic discourse, or scientific research, but by finding its own way to engage with truth or fact within an artistic context. I’m not entirely sure what that looks like, but the exhibition tries to open up space for that, perhaps by acknowledging contradictions, its own limitations and partiality, and by inviting visitors to form their own relationships to the contradictory narratives being presented. Maybe this is somehow akin to the idea of strong objectivity proposed by feminist theorist Sandra Harding.

AS: By approaching locality either through the feminist lens of situated knowledge or a horizontal reading of history, we challenge Western-centric hegemonic narratives. Do you think such complex, context-specific projects can only exist outside mainstream art hubs?

JK: I’m not sure, it depends a lot. There are peripheries and centers within every center and periphery, and these are in constant motion. Sometimes, I feel that places where audience or funder expectations for contemporary or visual art aren’t so entrenched in art traditions can actually be easier to navigate, to explore new ideas.

The professional audiences in major centers can be incredibly exclusive. They often work within a framework of specific ideas or theories that are taken very militantly. These theories and understandings frequently influence exhibitions or artistic work, which sometimes can be problematic. I’m not saying that I work with artists entirely outside traditional art education or systems, but when curating exhibitions, these expectations can be challenging. I wonder if an exhibition could present something that isn’t immediately transformed into art as we typically define it – something that resists being “turned into art.” There are hints of this possibility in the exhibition: certain works may appear very practical or direct, but by approaching them that way, you open up an incredible range of possibilities. For instance, there are practices where artists gather materials or work with them in a straightforward way and the thinking behind it isn’t always translated into traditional visual language or the expected language of art or science.

AS: I would say there is nowadays a renewed interest in materiality. This has always been tied to periods of crisis, much like the one we face today. The work of Jaana Laakkonen reflects on the material and the narratives it embodies, highlighting their mundane yet poetic connotations.

JK: Yes, and the truth that emerges from it doesn’t have to be worked through artistic representation regimes (Jaana prefers to use “reality” instead of truth). It’s about acknowledging that this type of knowledge, coming from ordinary, everyday conditions – where various social, economic, and other aspects are at play – is legitimate.

Take Laura’s [Soisalon-Soininen] practice, for instance. She’s organizing the upstairs room with scales and scaling, tailoring, and for her, this is also a spiritual practice. Then there’s Linda’s [Bolšakova] and Luna’s [Lund Jensen] works, another is a pile of rubble with a plant growing out of it. It’s a “simple” work, and maybe understanding the background of the plant isn’t necessarily crucial, and in Luna’s work sand is just sand. Both can communicate through affect and tactile experience. I think the certain sincerity of these works, and the knowledge they convey is simultaneously powerful or potentially dangerous. But is it inherently dangerous, or has it been made dangerous by the Western bourgeois male gaze, whose perspective tends to distance itself through abstraction, pushing certain types of knowledge to the margins or rendering them invalid? The exhibition is also about challenging what ways of knowing are valid.

At the same time, I wonder if a direct relationship with the material world could easily turn into a populist argument. There’s certainly an element of contradiction in the exhibition, but I don’t mind that. In fact, it’s one of the reasons I’m making this exhibition.

AS: How much risk-taking is allowed within the institution? I’m thinking of risk as the opposite of control, which was the first association that came to mind when I considered the term “measures.” At Frame in Helsinki, part of your mission involved analyzing and collecting data on the cultural scene in Finland, translating it into tangible and numeric terms. How do these different approaches interact or contrast with each other?

JK: Collecting data at Frame was more an aspect of the institution’s work that I wasn’t directly involved with. However, the need to navigate accountability within a heavily state-funded institution did shape my experience. While Frame is independent in its operations, it must still meet certain expectations from stakeholders and the local art scene. In my role, I tried to address this by subtly challenging the institution’s practices without direct confrontation by developing discourses and ideas that encouraged change from within the organization. At Frame I collaborated with Yvonne Billymore, we aimed to push the organization and its collaborators towards new ways of working.

In every context I’ve worked in, I’ve tried to find ways to perform within the constraints while pushing for change. Some efforts succeeded, others highlighted the limits of what could be achieved. For example, in the Measures exhibition, I sought to create a sense of trust through an honest acknowledgment of its limits. This involved carefully placing artworks and crafting narratives that reflected this approach, while also making subtle interventions in the space to convey a sense of lived experience and personal connection to the works.

This year, I am also co-curating the Finnish Pavilion with Yvonne. We collaborated with Vidha Saumya, who is also part of the show in Riga, along with two other artists Pia Lindman and Jenni-Juulia Wallinheimo-Heimonen. Pia works with alternative healing practices and Jenni-Juulia is a disability activist, sculptor, and performance artist. It was interesting because the entire exhibition was heavily criticized in the Finnish media. One comment in particular stood out questioning our decision to engage with “homeopathic” practice alongside work on physical disability.

There seems to be an argument implied here – disability activism is grounded in facts and real accessibility needs of the body, while alternative healing practices are seen as not being “real” healing or cannot be part of a legitimate justice movement. It made me think of where these power driven divisions come from and how they are reproduced in exhibitions and discourses around them.

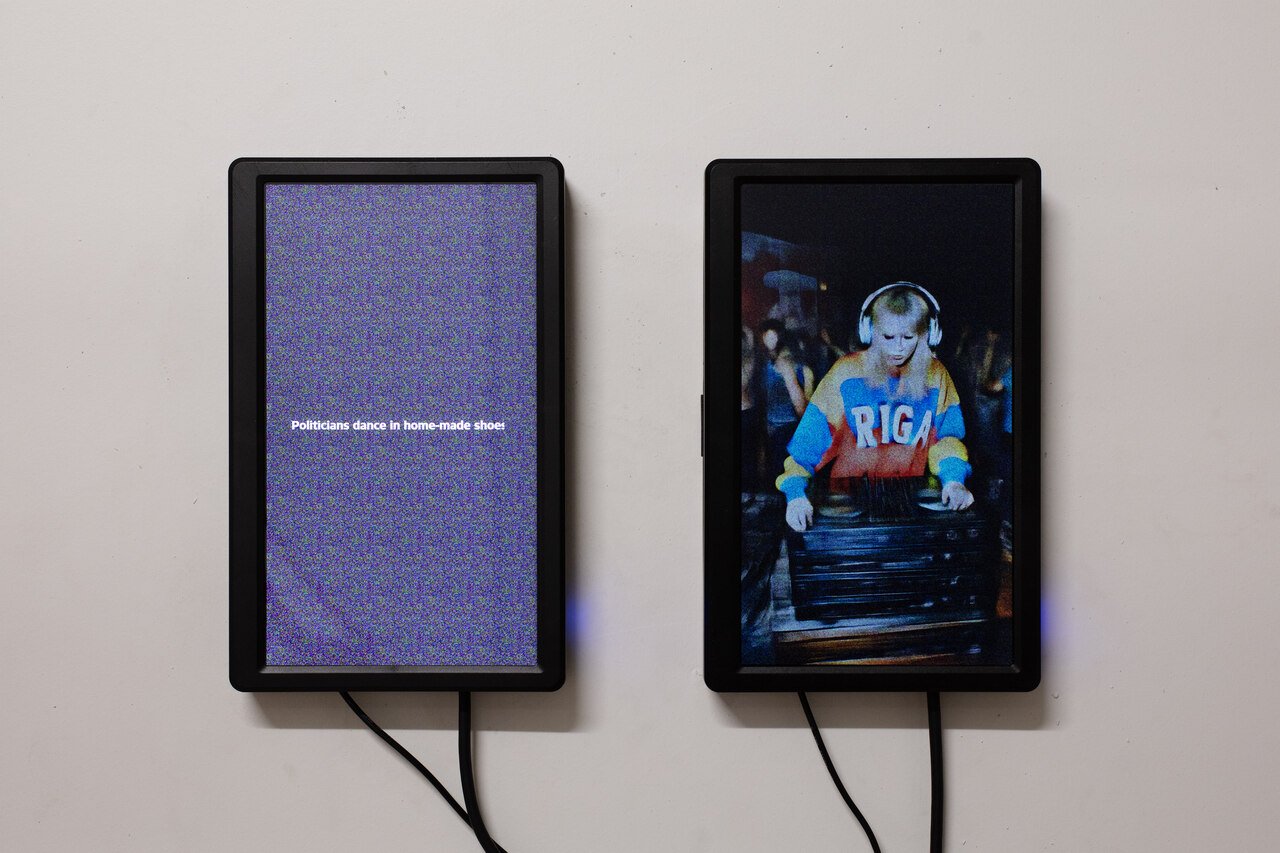

In Measures, some people saw the works of Jeremy Deller or Kristoffer Ørum as central because they dealt directly with this fact-versus-non-fact tension in political decision making and history writing, which are supposedly “real” political discussions. But for me, all of the works are equally important, not just those engaging directly with normalized political frameworks. I wanted to bring different kinds of works and practices together, allowing them to engage with ideas of politics, truth, and democracy in their own ways, not only in ways how these are debated in the media and political sciences.

AS: You were trained as an artist before moving into curating. Can you reflect on how this background influences your collaboration with artists? Additionally, I’m curious about how you build a framework for artistic research when working on new commissions. It’s always a challenge when approaching a local context as an outsider.

JK: In some of my earlier experiences working outside of familiar contexts, especially with commissioned projects, the artists themselves often became key informants. For example, I spent time talking with the artists during the installation. Līga Spunde’s work, in particular, was deeply tied to local histories and subcultures. It was another learning moment for me – something I couldn’t have anticipated or projected into the research beforehand. Sometimes, of course, conversations with the artists provide insight into their work, but surprises always come up, and I think that’s one of the beautiful aspects of the process. It’s a reminder that we can’t control the meanings that emerge. I see many exhibitions where there’s an attempt to build a very controlled narrative – whether through art historical references and canons or counter-narratives, but many times these projects stay within normalized ideological dichotomies and differences.

AS: There’s also some difficulty with research-based practices being co-opted by academia. Artists might end up illustrating established phenomena rather than using their unique position to explore and address the same questions in a more speculative and personal way. I really appreciate your decision to give artists the space in the exhibition’s handbook to discuss their work on their own terms. It’s a meaningful gesture that opens up the possibility of developing a new vocabulary and language. We’re all quite weary of institutional language and its constraints, but finding an alternative can be quite a challenge.

JK: I agree, many hybrid art-research-science programs and residencies are now adopting language borrowed from science and academia and it’s a challenge for artists to find their own language to speak about their work. In complex projects involving many people and logistics, balancing what you desire with what’s feasible can be difficult. Roberta Atraste and Sofija Kozlova, who edited the catalog, made a great choice to invite artists to tell their own narratives about the works, even if those might not be true.

In Venice, we considered the pavilion as a container for the works and aimed to transform it so that it not only supported the artwork but also those working within it. We began by asking what kind of exhibition space the artists would truly enjoy and how it could be designed to support their work.

AS: I think those basic, straightforward questions are often the ones we miss the most. While working in Venice, you highlighted the importance of collaboration in the project.

JK: In Venice, the process was quite different. We had two years to establish it and held regular meetings that we saw as workshops. At first, we didn’t fully define the purpose of those workshops, but over time, the collaborative aspect became clearer.

Sometimes, it feels like the work chooses me rather than the other way around. I do my own research, but a lot of my practice comes from working with artists – asking them how they want their work to be shown and what they wish for it. These basic questions about their needs and desires really shape the process. I try to appreciate the learning curve and work with people who make my practice what it is. One artist I’ve worked with, and who is also a dear friend from Helsinki, is Eero Yli-Vakkuri. In our previous collaborations, we’ve had earlier situations where he would bring more works to the space, and I’d find myself taking some out through another door. So it’s often about expanding the space or the thinking, and then I find myself negotiating where to draw the line or how to make modifications so that everything comes together. What’s incredibly interesting is that things don’t always need the same amount of space to be perfectly balanced. Some works may spread throughout the space, even if they’re not immediately tangible, much like other elements such as the context or the street outside.

AS: What were the biggest challenges you encountered?

JK: I think it always comes down to time and production conditions – how much you can reasonably expect from people and from yourself. Survival Kit uses vacant, empty buildings, though I find the term “empty” problematic because nothing is truly empty. I’ve always approached exhibitions with the idea that it’s not just the show, the artworks, or the space that defines the exhibition, but everything surrounding it, including what you experience before you arrive. What I particularly appreciated about Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s Istanbul Biennial, despite its many challenges, was how it mobilized and reflected the city through the exhibition. I’ve been trying to achieve something similar on a smaller scale by incorporating the streets and the ways people move between venues into the exhibition experience. It’s about expanding the context and bringing in unexpected knowledge.

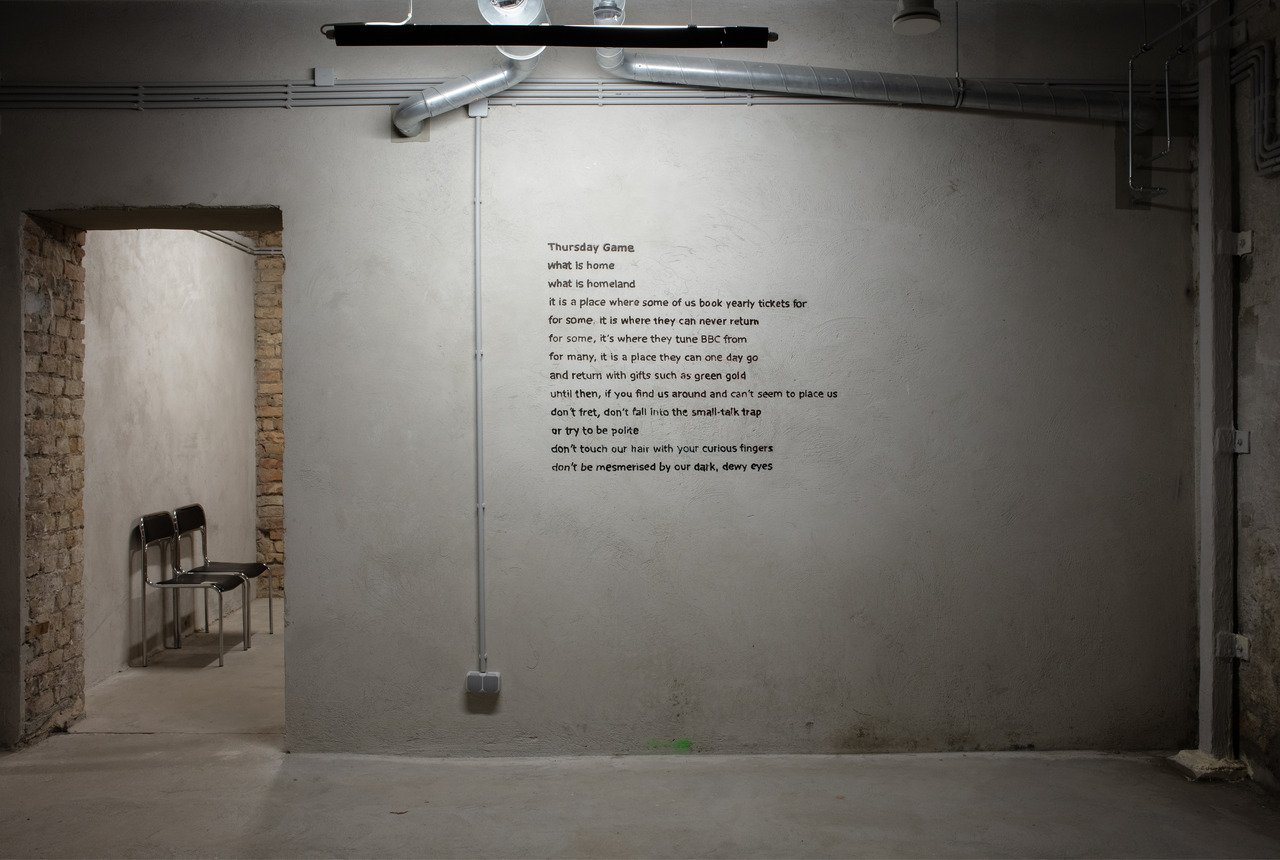

AS: Would you say that one of the roles sound plays in your exhibition is to enhance the sense of fluidity and bridge the in-between spaces? I’m also interested in non-auditory repetitions and rhythms that you incorporate into the exhibition, such as the poetry of Vidha Saumya that accompanies us in all three venues, the ticking of the clock, and the movements on scaffolding.

JK: I haven’t specifically researched sound with that intention; it rather developed organically. One part of Monika Czyżyk and Neil Luck’s work includes a sound element in the courtyard of the Amatu Street venue, but it’s part of a larger installation at the Strazdu Street venue across the river that features video, sound, and material work. At the Smilga venue, there’s a piece by Luna Lund Jensen that fills the space with a choir singing, evoking how sand or dunes in Northern Denmark might “sing” or how sound moves through the environment. In the basement at Amatu Street, sound plays a very prominent role, perhaps because it references subcultures and alternative art scenes embedded in the urban context and closely tied to music. My aim of incorporating these “rhythms” with repeating aspects of Vidha’s poetry, Luīze’s works with clocks or Toril Johannessen’s graph works, was to create connections through the venues but also have a feeling that visitor moves through mundane daily environment of repeating information that affects you differently in different spatial and social contexts. You know your environment through these repetitive rhythms of information and narratives.

AS: At Strazdu Street, you exhibit Renee Green’s video installation Secret from 1993, a testimony on the collective experiment held at Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Firminy, France. There is a bridge between this artistic experiment in cohabitation and the venue. Could you elaborate more on these links and, perhaps, the failed utopias they carry?

JK: Every venue of the exhibition has a different architectural setting and historical function. The Strazdu Street venue is a quite new, street level space of a domestic house that is owned by the family who has let us use it. The construction of the space is not finished yet, and I believe they envision renting it out as offices. The venue itself is located in the neighborhood across the river from central Riga, the neighborhood that has been undergoing gentrification in recent years. Renee’s piece is one of the starting points for me in the exhibition. It addresses the relationship between artists, the body, and modernist architecture and its utopias. More broadly, it explores how the body produces knowledge about its environment through tension. Is my knowledge about the space coming from fitting or unfitting in relation to it? Can I express that knowledge and how does it become public, or does it remain secret?

AS: To end this conversation in an activist tone, I wanted to ask you about your understanding of “measure” as a call to action. I’ve been thinking about strategies like bringing the street back into the exhibition space, as seen in Jeremy Deller’s work or Aimée Zito Lema.

JK: There was a bit of wordplay behind the title Measures, referring both to standards and measurements, and to measures as actions that need to be taken. I’m affected by feminist theorist and physicist Karen Barad’s ideas on knowledge production and their reading of quantum physics. Their perspective is speculative and can be explosively insightful. When we talk about knowing something, there’s often a distinction between the knower and the known, but the act of measurement itself – this process of knowledge production – creates these divisions. Essentially, the act or apparatus of knowledge-making can create subject-object relations but also completely different worlds, making it a world-making practice.

In this sense, “measure” reflects the idea that through knowing, we shape the world. The exhibition itself becomes a form of world-making. By approaching it differently, we can make a difference differently, as Barad suggests. This ties into the critical issue of inside and outside. It’s not just about bringing the street inside the exhibition; it’s also about acknowledging the processes and histories behind the artwork. The artworks become remnants of this process, that re-make the difference between outside and inside.

Artist(s): Māris Ārgalis, Malin Arnell & Mar Fjell, Monia Ben Hamouda, Linda Boļšakova, Monika Czyżyk & Neil Luck, Jeremy Deller, Renée Green, Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni, Toril Johannessen, Jaana Laakkonen, Kristoffer Ørum, Gerda Paliušytė, Yuri Pattison, Rena Rädle & Vladan Jeremić, Luīze Rukšāne, Vidha Saumya, Līga Spunde, Isabella Solar Villaseca & Lou Mouw, Laura Soisalon-Soininen, Shubhangi Singh, Jon Benjamin Tallerås, Luna Lund Jensen, Eero Yli-Vakkuri, Konstantin Zhukov, Aimée Zito Lema

Exhibition Title: Survival Kit 15 “Measures”

Venue: 4 Amatu Street, 34a Eduarda Smiļģa Street (“Smilga”), 4 Strazdu Street

Place (Country/Location): Riga, Latvia

Dates: 06.09 – 06.10.2024

Curated by: Jussi Koitela

Photos by: Kristīne Madjāre