Andrei Siclodi

The concluding exhibition of the Büchsenhausen Fellowship Program for Art and Theory 2023-24, entitled The Secret Life of Plants and Trees, explores today’s growing antagonisms and shifts in identity politics. With the help of and in exchange with botanical agents, the works of Agil Abdullayev, Tatiana Fiodorova-Lefter, and Hori Izhaki examine pivotal themes, including queer cruising practices in repressive societies, decolonial questioning of (post)Soviet identity formation, as well as the (im)possibility of socio-political identity constructions as an Arab Jew in the context of Israel-Palestine.

With multimedia, partly immersive installations, each artist shapes aesthetically and thematically multi-layered spaces for reflection, which at first glance may seem disparate. However, within the joint presentation, they prove to be coherent components of critical observation and (self-)questioning. The title of the exhibition plays with the potentiality of what is shown without wanting to fulfill the expectation of botanical secrets that might lie dormant in the respective works. Instead, plants—from grasses to trees—prove to be physically and rhetorically present entities that link all three contributions, making it possible to experience commonalities across the different themes yet taking up specific discursive positions while actively contributing to the development of the respective narratives.

Tatiana Fiodorova-Lefter’s work is the first contribution visitors encounter upon entering the exhibition. In Büchsenhausen, the artist worked on a new chapter of her long-term research into the post-Soviet space and the search for her own identity. Born and raised in the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, she completed her artistic training after the end of the Soviet Union in the 2000s in Chişinău, the capital of today‘s Republic of Moldova. Thus, the resulting existential identity dichotomy formed in two worlds—Soviet modernism and neoliberal capitalism—and its (re)construction in the face of the socio-political upheavals of recent decades are at the heart of the project. Fiodorova-Lefter collects fragments and “scattered pearls” of memory in order to associatively bring them together in drawings, paintings, clay, concrete, and mosaic works, making them tangible in a three-dimensional space. The artist developed essential components of the installation in thinking spaces beyond her everyday life at Büchsenhausen. These resulted in, among other things, the implementation of the in-situ work Monument of Contemplation on the terrace of the Künstler:innenhaus. The window of her home studio became an improvised balcony allowing her to interact with unknown passersby, including the artist Theresa Mauser, who ultimately gave her the opportunity to practice ceramic craft.

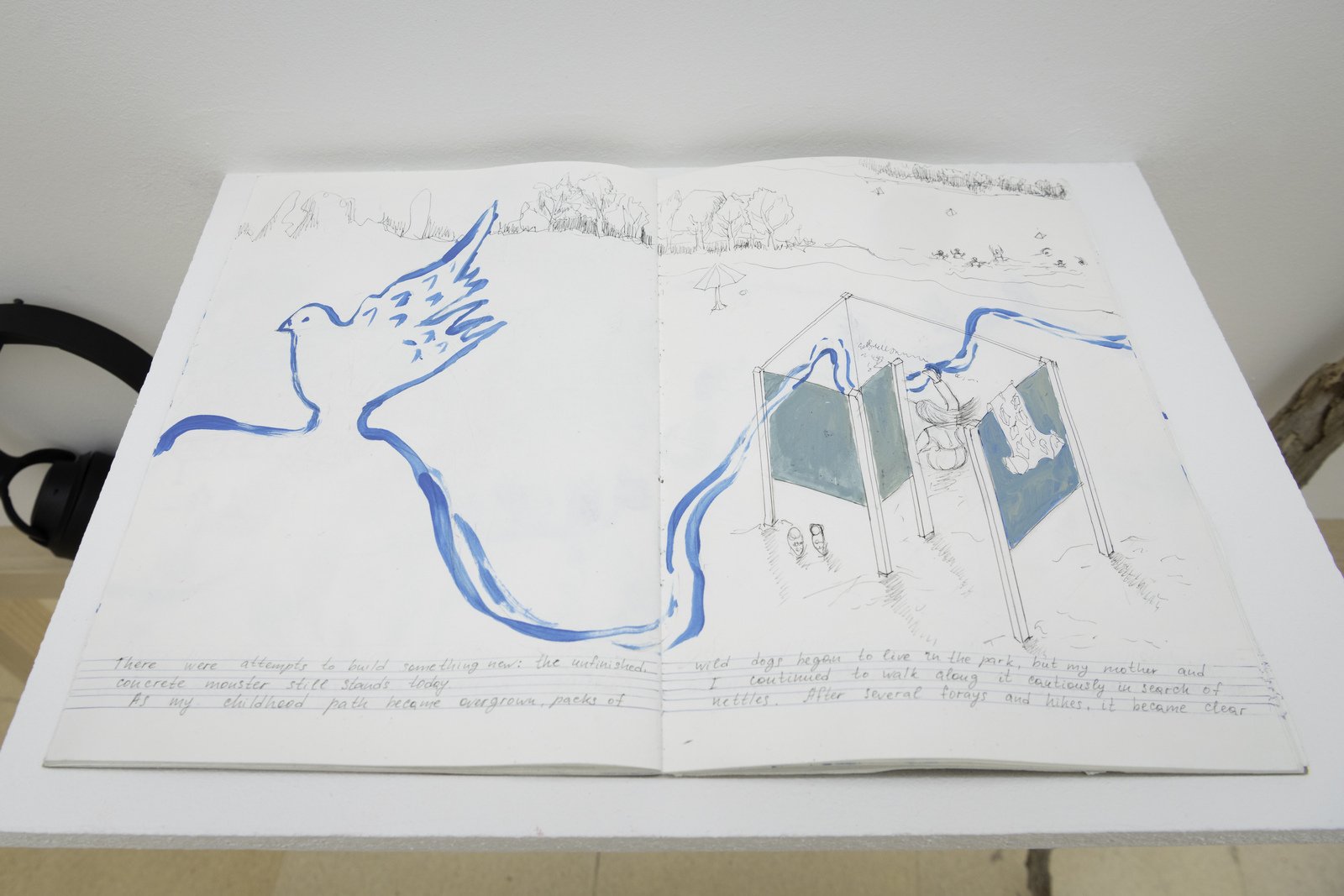

The installation consists of two main areas: A “changing room” that serves as an exhibition space for personal memories, a glass cabinet and a series of monochrome paintings that form a modernist-abstract counterweight to the narrative level within the “changing room” and are part of a broader exploration of decoloniality. The “changing room” materializes as a memory of an irretrievably past life when everything seemed bigger to children’s eyes: a place of carefree ease that unfolded in both urban and rural contexts. Thus, the outer surface of the “changing room” is covered with a light blue limewash paint, similar to that used then and now in the Moldavian countryside for exterior house walls. Upon entering this space, it is apparent that it is a double “changing room” divided by a light, translucent curtain. The division goes back to the original memory spaces “city” and “village”. However, these overlap in the individual memory: events that took place here or there are stripped of their original affiliation and relocated, as do the objects with which they were contextually linked. Their shapes and colors wander between the different stations, creating new connections; like the round table from her childhood, now hanging as an ornate wall object, reflected in the yellow circle of the curtain. The yellow refers to the “gold” of mămăliga, the traditional polenta dish made from the grains of păpuşoi, the corn plant, which is shown in the exhibition along with a dried nettle. Corn and nettle are the two plants that symbolize the rediscovery of Fiodorova-Lefter’s own past, which has been overwritten by the neoliberal-capitalist impetus of recent decades. The traces of the post-Soviet upheavals have inscribed themselves in the urban and rural structure, leaving former modernist flagship projects in ruins. The artist reconstructs such buildings in paintings and ceramics. One of those is the roof of Romashka/Romaniţa House, which was built in the 1980s and was considered to be a modernist architectural jewel which later decayed—but is still the tallest building in Chişinău. The modernist form of Romashka’s roof meets the playful ornamentation of the rural style of downspouts; tiles from an old stove become steps—a reference to the omnipresent front steps of rural houses in Moldova. At last, the mosaics embody iterated fragments of memories of a lost time, crucial to the artist’s personal development, now rediscovered and reinterpreted, allowing the new to flourish on the ruins of the past. Fiodorova-Lefter summarizes the various traces and forms in a carefully composed artist’s book, which takes up elements of the presentation in drawings and paintings and condenses them into a lingual-visual narrative. While paging through the book, visitors have the chance to listen to a song from the artist’s childhood and hear the essay from the book read aloud.

Finally, a visual quote is to be found inside the “changing room”: a girl playing with plants. Fiodorova-Lefter repainted an image that was originally mounted on the glass façade of Café Guguță[1], a soviet modernist building threatened with demolition, in shades of gray—a kind of self-portrait of the artist that not only foregrounds her care for plants as symbolic recall of forgotten roots but also creates a visual bridge to the second part of the installation. The performative gray paintings on the wall outside the “changing room” take their different shades from the image of the girl and deconstruct it chromatically—a formal reference to the necessity of self-questioning in connection with the imperative process of decolonization and the associated recognition of this process’ dialectics. As the Janus-faced stone in the glass cabinet shows, modernity has two faces—one that looks to the unwritten future, while the other looks back and processes. Here, it is materially based on a supporting structure in the aesthetics of socialist modernism, which, in the case of Fiodorova-Lefter, forms the foundation for new growth. This growth ultimately manifests itself in the improvised “tire pots” in front of the Kunstpavillon, which, in the months leading up to the exhibition opening, were set up on the terrace of the Künstler:innenhaus Büchsenhausen. The corn and stinging nettle plants sown therein by the artist grow as a symbol of recurrent renewal.

In Agil Abdullayev’s three-channel video, trees are both confidential and protective agents. Radicals Between Trees and Dicks, the title of the installation, is the first artistic outcome of a years-long research into queer cruising culture in Azerbaijan and some neighboring countries in the Caucasus region and Central Asia. The term “cruising” refers to the pursuit of sexual encounters between homosexual men in public spaces, such as parks, or discreetly designated private spaces. Over the past five years, Abdullayev has visited about thirty such sex spaces in these regions, recording their own observations and the experiences of others in interviews, conversations, and visual recordings. The research explores the various facets of cruising in deeply repressive societies where homosexuality is still highly tabooed, and people face massive discrimination and violence because of their sexual orientation. The interviews and conversations that Abdullayev conducted with protagonists in these regions, along with experiences of their own first sexual encounters in “darkrooms,”[2] form the narrative of the video installation. Since some protagonists live in countries where homosexuality is either subject to prosecution or legally decriminalized but still ostracized by the majority society and, thus, target of violence, Abdullayev decided to alienate or anonymize the voices of the interviewees. The narratives, divided into eleven acts in the video installation, focus not only on the first experiences of cruising but also on the experiences of “professional cruisers”. Less common cruising locations such as saunas and situations in which the hedonistic aspect collides with socio-political circumstances—be it the extended military mobilization in Putin’s Russia in the fall of 2022 or possible discrimination due to migration—are not left unmentioned.

During their stay in Büchsenhausen, Abdullayev cast five dance performers to choreograph and perform the collected stories and, by this, make them more tangible. The artist combined this process with researching Azerbaijan’s cinematic history. According to Abdullayev, Azerbaijani cinema during the Soviet era primarily promoted national and moral ideals. Especially in the films made from the late 1950s onward—such as The Tempestuous Kura (1969) and If Not That, Then This (1956) by Huseyn Seyidzadeh, Dada Gorgud (1975) by Tofig Taghizadeh, or Nesimi (1973) by Hasan Seyidbeyli— established family values and concepts such as “masculinity” came to the fore. Abdullayev is interested in films of the period in which dance or group choreography was used as a means of dialogue and narration, and in which unconventional characters with negative connotations appeared. Specific excerpts were selected for the performers to use as a reference. The respective performances were then filmed in the minimalist setting of a blue-lit dance floor and in public space.

After the introductory part, in which Abdullayev describes their first experiences with cruising and darkrooms in the Bassiani nightclub in Tbilisi, the eleven acts take us to the parks, saunas, and private party rooms of Baku, Tbilisi, and Almaty. While the stories unfold, the three projection screens alternate between shots taken at the respective original locations and the choreography developed together with the five performers in Innsbruck; they change position similar to a dance and contribute to the story’s respective atmosphere via film cutting. The camera switches lasciviously or in rhythm with the music between long shots and facial details, almost “snuggling up” to the protagonists’ bodies to add a dynamic note to the dance’s playful expression.

In the anteroom of the video installation, visitors encounter five photographs. Four of them show “sexualized places”, anonymous park corners where cruising takes place. The fifth image is a portrait of Paata Sabelashvili—a pioneer of cruising culture in Tbilisi, to whom Abdullayev pays homage by including him in the exhibition.

Hori Izhaki’s work project during the fellowship in Büchsenhausen became tragically topical after the Hamas massacre on October 7, 2023, and the subsequent ruthless military counter-offensive by the Israeli government against the civilian population in Gaza. Izhaki deals with the history and identity construction of herself and her own family, which appears to be symptomatic of Arab Jews: “Born and raised in Israel in an Arabic Jewish family with roots in Morocco and Iraq, I had to face challenges of memory throughout my life,” Izhaki writes. “Growing up, I was not told I was Arabic, nor was the history of my ancestors taught in school or part of general knowledge. In order to be Jewish Israelis, Arabic Jews like me, inserted their own selves into the Holocaust and entered a virtual memory where they belonged to the shared history of the land of the survivor. Since the Arabs were considered the enemy, there was no place for Arabic Jews and their story in the national narrative of Israel. Living in Europe, I am invited by societal framings to perform my virtual Jewish European roots. I am welcomed here not as an Arab but as an Israeli – a modified/deleted Arab who has been given roots in the European story by the country of her birth. I can travel to, work, and live in Germany, Austria, Europe, in the ‘Heimat’ of a virtual persona, thanks to Israel, while in Iraq, my father‘s land of origin, I am not welcome. But as much as I am culturally modified, my face, my skin, my hair were not changed. And on first sight, before I get to share my persona, I am not perceived as a Jewish Israeli Arab, I am just an Arab. So, occasionally, I get a glimpse into what it means to be an Arab in Europe.”[3] This, of course, is a racist treatment that stops as soon as one realizes that the artist is Israeli. For Izhaki, this identity proves to be the result of an implanted memory closely linked to Israel’s socio-political self-image and the culture of remembrance in Europe, especially in Germany and Austria.

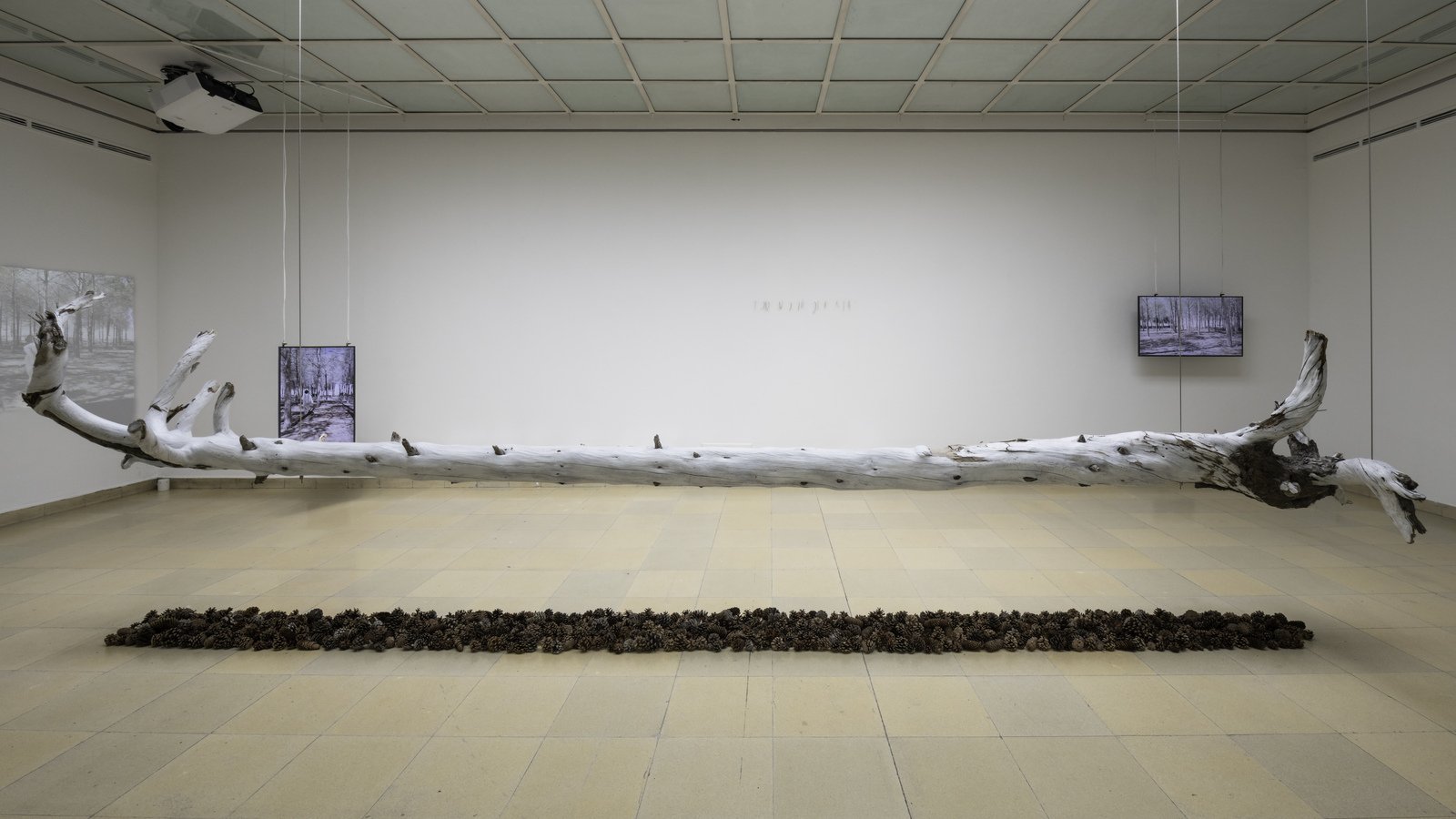

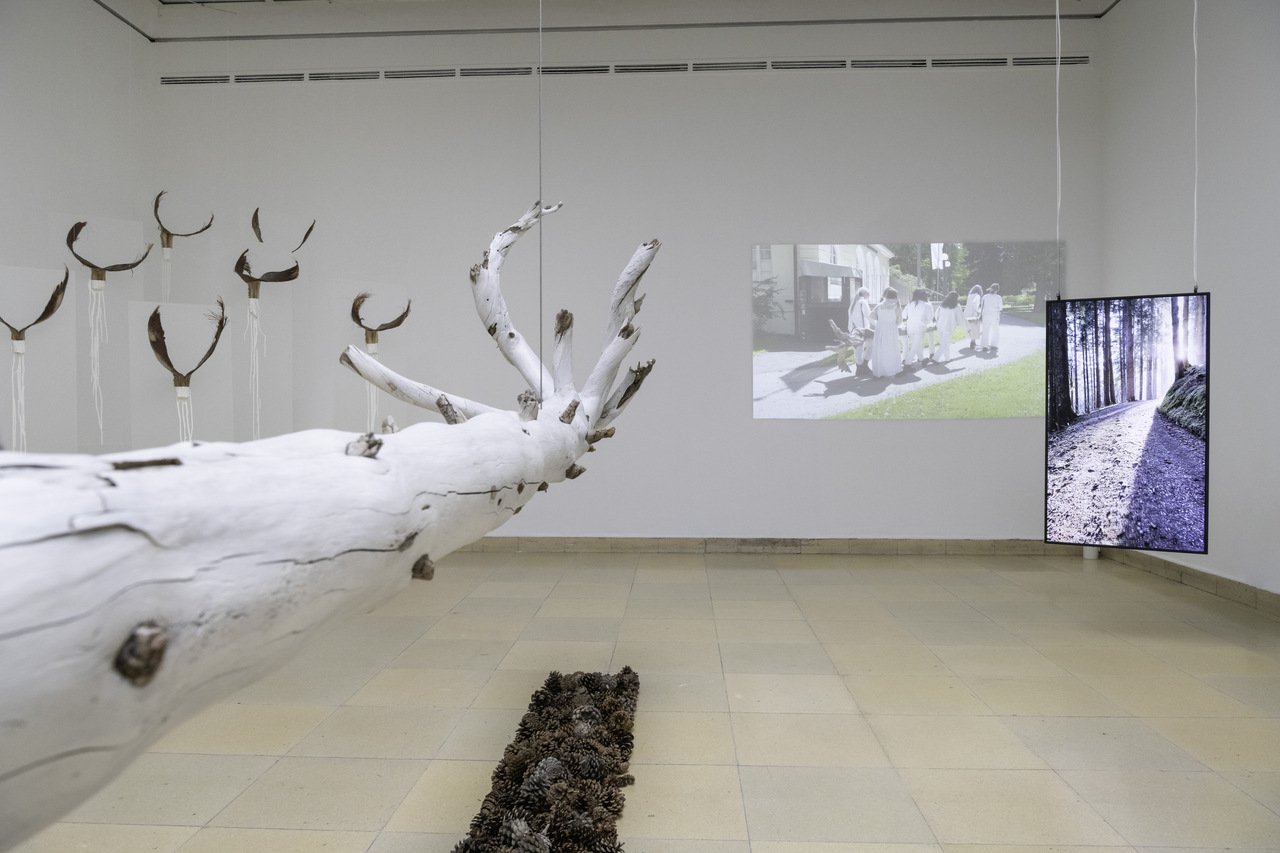

Izhaki’s multimedia installation is titled illi yidri willi ma yidri hafnat ʻadas (The one who knows, knows, and the one who doesn’t know, a handful of lentils). This is an Iraqi idiom used to show that there is something significant behind something trivial. Following this idiom, Izhaki takes up the leitmotif of (European) conifers, which were systematically planted by the Jewish National Fund (JNF) on land pur chased for settlers in Israel-Palestine since the beginning of the 20th century, along with other tree species, and enjoyed great popularity due to their appearance and ability to protect the soil from erosion. Many of Israel’s parks still contain trees planted on behalf of the JNF. But behind the superficial banality of a conifer lies a settlement policy that, from the very beginning, was concerned with securing living space for immigrant settlers.[4] In addition, for many Jewish immigrants from (northern) Europe, Russia, or North America, the conifer was a kind of reminder of their former homeland. The new settlement thus evoked a sense of familiarity. Izhaki takes up this historical fact, but in a very different way: She takes a carefully selected, already dead tree trunk from the bed of the Fallbach creek near Innsbruck with the intention of taking it to Israel-Palestine in a non-Zionist manner after the exhibition. The tree trunk, which still has roots and crowns at both ends, now “floats” in the middle of the back room of the Kunst pavillon above the cone-covered floor, becoming a performative body onto which the artist transfers the attribution of identity she has experienced. The trunk was taken from the creek bed by eight women dressed in white, carried through the forest into the city and brought into the exhibition space, where Izhaki whitened the tree’s bark. Upon closer inspection, the brittleness, scars, and the fragility revealed in the myriad details of the tree’s body convey a haunting sense of vulnerability and yet unwavering endurance.

Around the floating tree, a multimedia arrangement unfolds that, similar to memory processes, shifts and blurs the boundaries between reality and truth, between the experienced and the imagined. Ana (= Arabic: “I”) materializes as an Arabic window milled into the wall of the Kunstpavillon. At its center, is a delicate brass structure reminiscent of the Arabic letters Alif and Nun (= “I”) that supports two small water jars from which delicate Tradescantia zebrina plants, also known as “„the wandering Jew,” grow. Thus, Ana combines Jewish and Arab identity markers in a metaphorically charged, performative in-situ intervention: Over time, the “wandering Jew” plant will overgrow the Arabic “I” and eventually remove it from view, while the supporting Arabic structure remains. Ana also plays with the idea of a history that never happened— the inscription of Arab architectural and everyday traditions into the history of Central Europe. Izhaki contrasts this contemplative, seemingly peaceful arrangement with a “herd of rams” in the room’s opposite corner: Seven aggressive-looking horned entities appear to be storming the room. On closer inspection, the “horns” turn out to be palm fronds extensively painted with white color, which ran down and dried, transforming the “rams” into bearded figures. The “rams” paraphrase the Genesis story of Isaac’s non-sacrifice, to whom the artist makes a connection through her family name (Izhaki) and the family’s immigration history.[5] The work’s seemingly ironic title Nie Widder (a play on the German phrase “nie wieder/never again”) can also be interpreted as a comment on the German and Austrian “Erinnerungskultur” (Culture of Remembrance) with regard to the Holocaust, which, as mentioned at the beginning, was internalized as a virtual memory by the artist’s family of Arab descent. Izhaki takes up this circumstance several times in the installation.

In the five-channel video installation, the artist ultimately fuses the various components and levels of action into a dreamlike, non-linear narrative that blends actual and “implanted” European memory, her own family history, the history of Israel, and other identity-forming events. The main protagonists are four characters: the Arab, the Jew, the European, and the artist’s maternal Moroccan grandfather. They find themselves in suddenly changing landscapes, where European environments become Israeli and vice versa; where the music of Bedřich Smetana’s symphonic poem The Moldova, which, according to the artist, emerged from the same European folk song melody as the Israeli national anthem, merges into an Arabic interpretation; where the artist’s family thoughtfully collects pine cones in various forests in Israel-Palestine; where the tree trunk, carried by eight women (because women, according to Izhaki, are able to tackle profound problems with patience, care, and humility), finds its way out of the forest … In the process, we realize more and more that temporality is relative in terms of experience, and we humans should consider the “healing patience” of plants as exemplary, especially in times of profound social and interpersonal upheavals, guiding toward a new, prosperous coexistence for all.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guguță_Café

[2] Darkrooms are sparsely lit rooms for sexual encounters, mainly between homosexual men. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Darkroom

[3] https://www.buchsenhausen.at/en/fellow/hori-izhaki

[4] see Alon Tal: Pollution in a Promised Land: An Environmental History of Israel, 2002, especially the chapter “The Forest’s Many Shades of Green”, 69-111.

[5] According to Hori Izhaki, her grandfather was given a new, non-Arabic name, Izhaki, when he immigrated to Israel from Iraq.

Artist(s): Agil Abdullayev, Tatiana Fiodorova-Lefter, Hori Izhaki

Exhibition title: The Secret Life of Plants and Trees

Venue: KUNSTPAVILLON

Place (Country/Location): Innsbruck, Austria

Dates: 24.05. – 10.08.2024

Curated by: Andrei Siclodi

Photos by: Daniel Jarosch