Andrii Ushytskyi

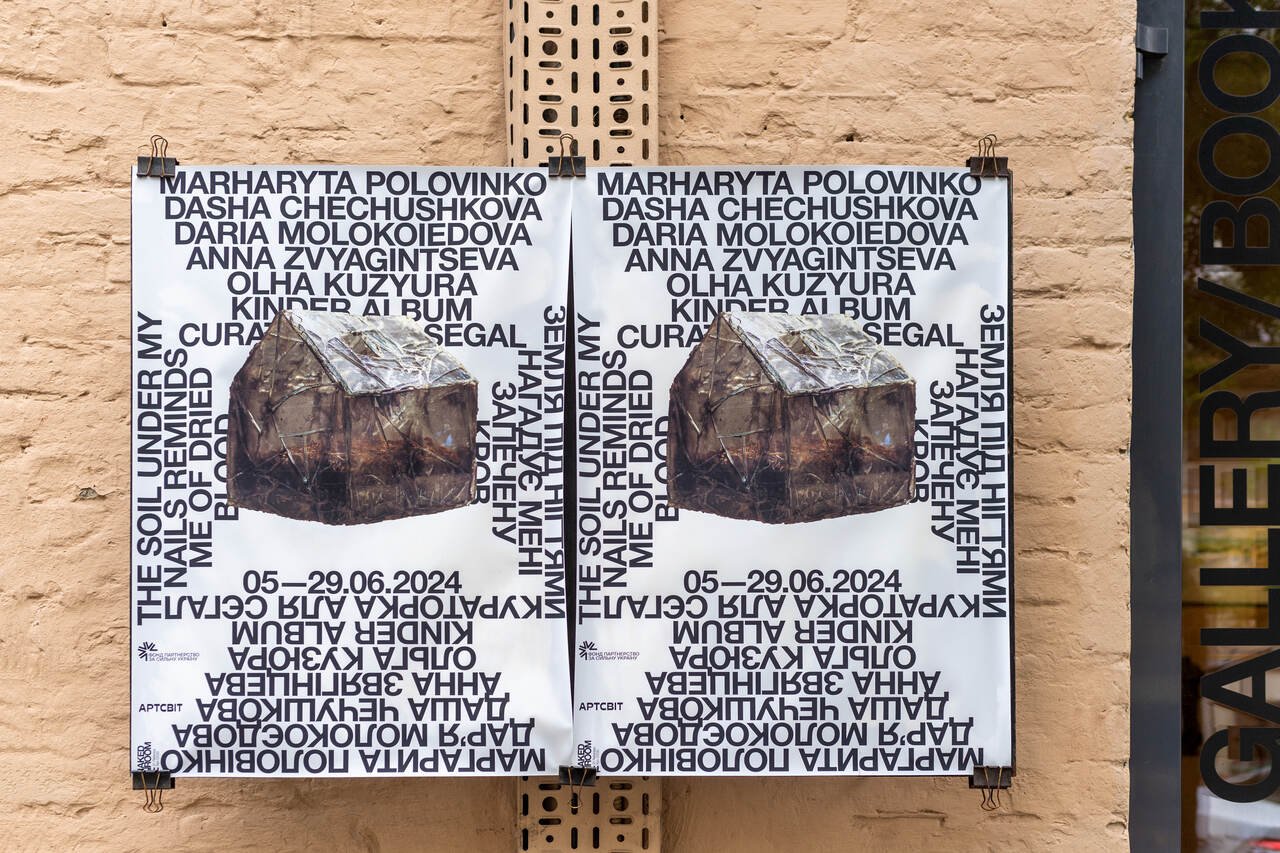

The Soil Under My Nails Reminds Me of Dried Blood, the exhibition curated by Ukrainian art historian and researcher Alya Segal, was set to welcome its viewers at The Naked Room gallery in Kyiv from June 5-29th, 2024. When I was invited to attend the opening, I thought about not going as the early days of June kept bringing more grim news from the frontlines. My Instagram feed became a somber scroll of obituaries; my friends mourned and shared photos of their loved ones lost to the war. I didn’t know those people; I learned about them posthumously and felt a heavy duty to carry their names somewhere deep within me. The weariness of it all made me want to see the exhibition on another day, a quieter day when the space would be empty of people. After some brief episodes of self-persuasion I ended up going. “Just for 10 minutes,” I promised myself, “I will only congratulate Alya on the opening, have a quick look at the works, and then leave.” The plan almost worked. The only deviation was meeting a good friend of mine who had also come to the gallery that day. We found a quiet corner to share our life updates, discussing how hard it was to keep working and functioning properly with calamity as our backdrop. How – and where – do we find the strength to keep going? Silence. I felt slightly better after our conversation but followed my initial plan: I congratulated the curator and left. A few days later, I returned to the gallery on my own.

The Soil Under My Nails Reminds Me of Dried Blood is spoken through the voices of six female Ukrainian artists, weaving together the women’s testimonies of war that capture collective sorrow and the shared experiences that Ukrainians continue to endure. The title is derived from Segal’s personal story of tending to her mother’s garden. While pruning old tree branches and pulling out weeds, she noticed how the soil on her hands resembled dried blood. War has an unpredictable way of intruding into everything we do, say, or remain silent about. It changes how we perceive the world, as the relatively peaceful things begin to evoke associations that lead the human mind toward scenes of cruelty, horror, and death.

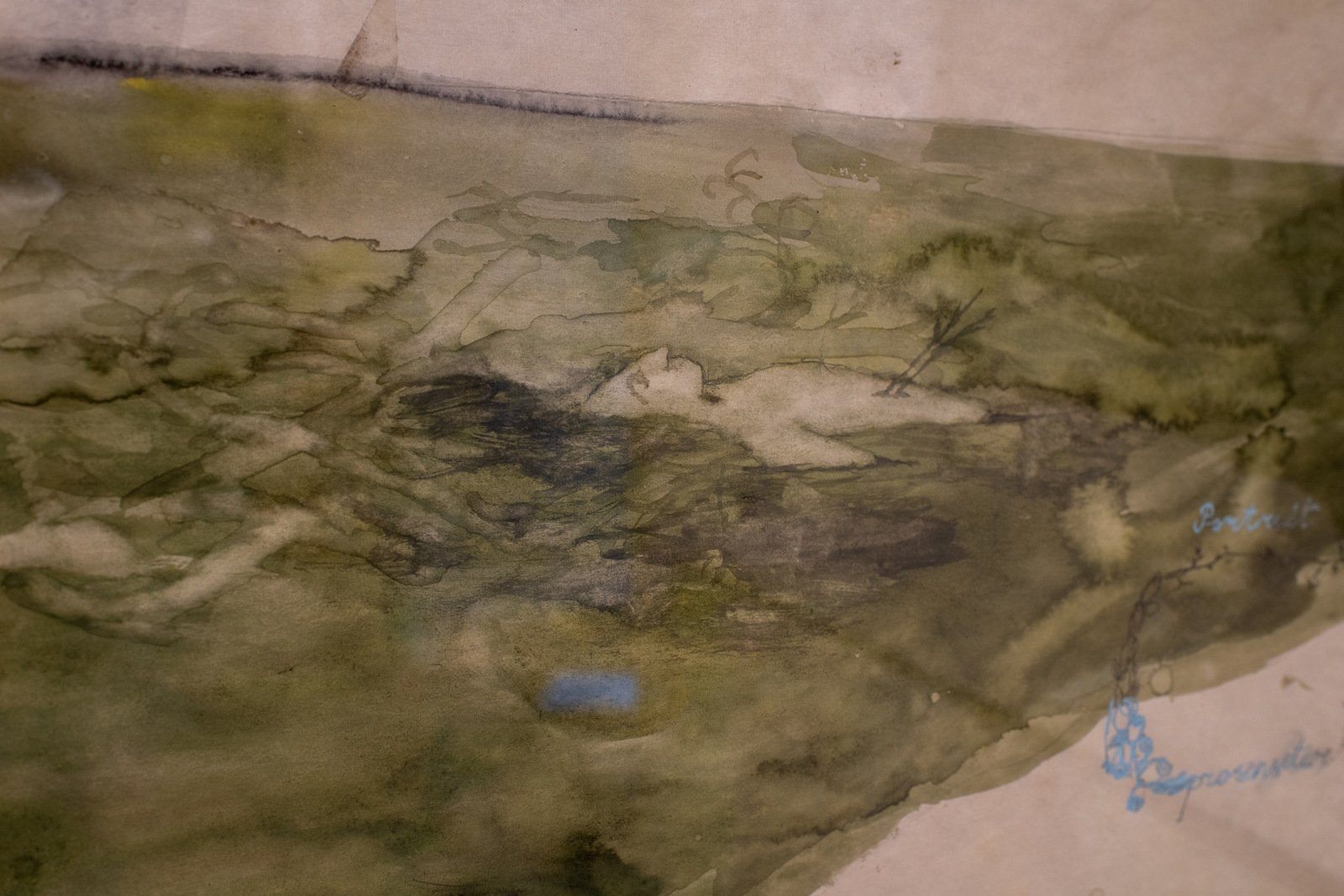

I once noticed that hearing someone say the word “blood” now elicits a visceral reaction in my body – a knot in my stomach – which is the same feeling I get when sensing impending danger. I know where this reaction comes from. All Ukrainians do. It was this feeling I encountered during the exhibition; however, not when hearing someone say the word, but when I saw blood myself. Marharyta Polovinko currently serves as a volunteer paramedic in the Ukrainian military. In her works, she depicts landscapes, news events, stories of acquaintances, and personal memories from the full-scale war. The paint she uses to convey the excruciating pain of the current reality is her own blood.

In a country at war, where complete detachment from the catastrophe – both physical and emotional – is impossible, contemporary Ukrainian artists grapple with the burden of addressing suffering while enduring the trials of constant re-traumatization. Although the intensity of pain may seem to diminish over time, works like Polovinko’s force us to confess that the pain remains profoundly raw. The body that holds memory also holds pain. It is the inescapability of pain, the helplessness of having to just sit with it, that I felt when contemplating Polovinko’s pieces.

Reflecting on her works for Solomiya magazine, the artist drew parallels between the way blood changes color on paper and how the feeling of pain transforms over time, “Initially vivid, much like the experience of a traumatic event, it’s intensely painful, leaving you unsure of what to do. Then it steadily darkens, transitioning from bright red to brown, calm, or even slightly greenish. The same appears to happen with our overall pain.” Before the full-scale invasion, the artist painted scenes from her native town of Kryvyi Rih, known for its iron ore mines. She recalls that the soil there, because of the ore, would turn red in rainy weather, giving the impression that the entire city was bleeding. After the full-scale war broke out, Polovinko traveled to southern Ukraine to help rebuild houses destroyed by shelling and eventually joined a CASEVAC (casualty evacuation) crew to evacuate the wounded from the most challenging frontline areas. In her most recent works, the artist no longer uses blood but employs other materials such as watercolor, pencils, and pens to capture her experiences.

Memory emerges as one of the central themes in the exhibition. While the artworks predominantly speak to collective Ukrainian experiences, they also delve into personal contexts. This diversity of individual memories exposes the divide among Ukrainians, who, despite sharing the common ordeal of war, each endure their own hardships. “Are we ready to listen to the stories of the dead? Are we ready to hear the stories of the living?” Segal poses these questions in her curatorial text. “Are we ready to share those stories?” I would add. The growing fatigue and persistent cruelty make it increasingly difficult to communicate the experience of war the longer it continues. Keeping one’s pain to oneself might seem like an easier way to avoid the guilt of complaining, especially while thinking that others endure greater suffering. However, this approach often leads to a growing sense of loneliness. When we had a chance to talk one-on-one, Segal noted, “In a way it is easier to tell the stories of the dead because they do not lead to uncomfortable questions.” And I would add here too, “It is because it spares those who perished from having to relive and retell their suffering just to make others understand it.”

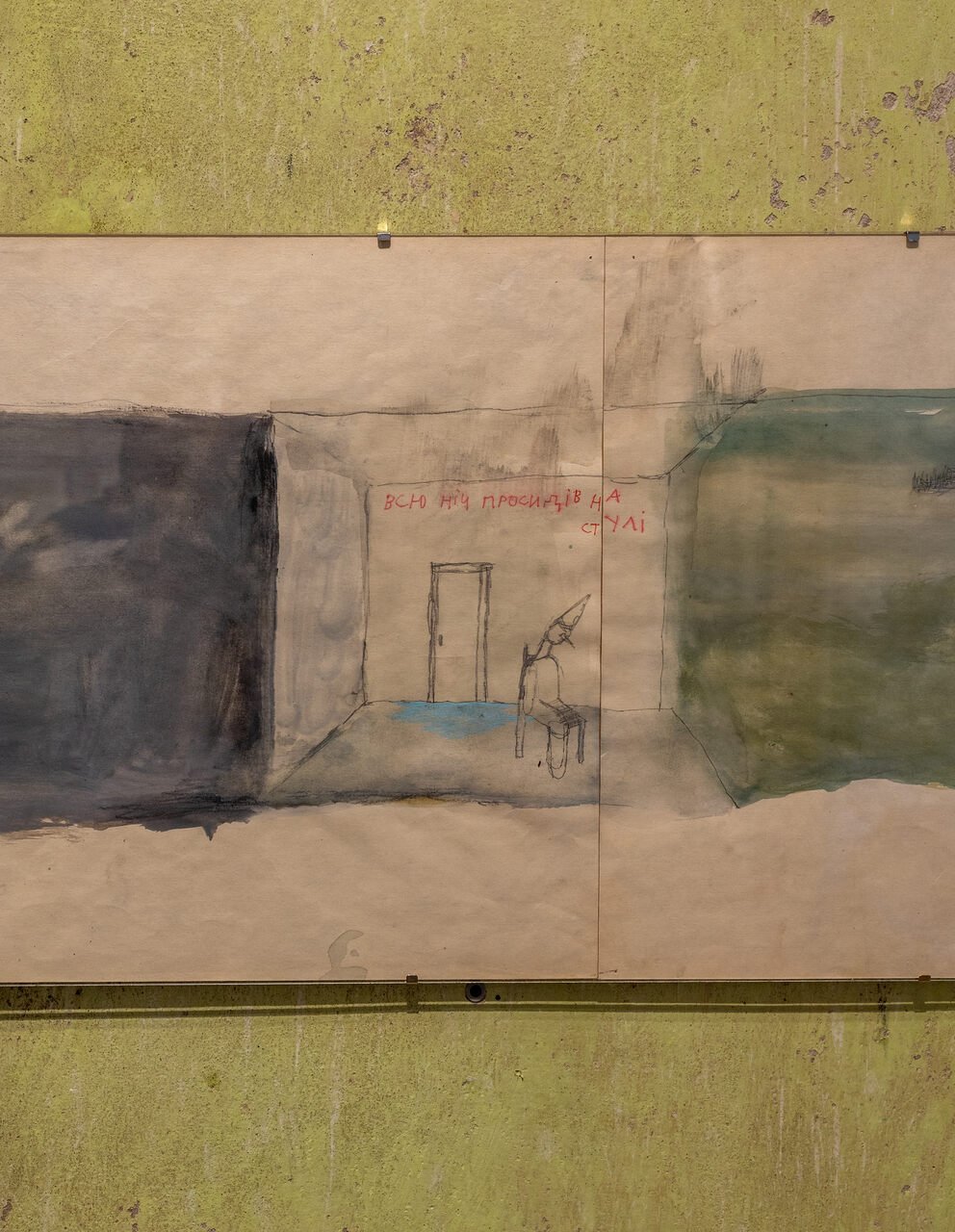

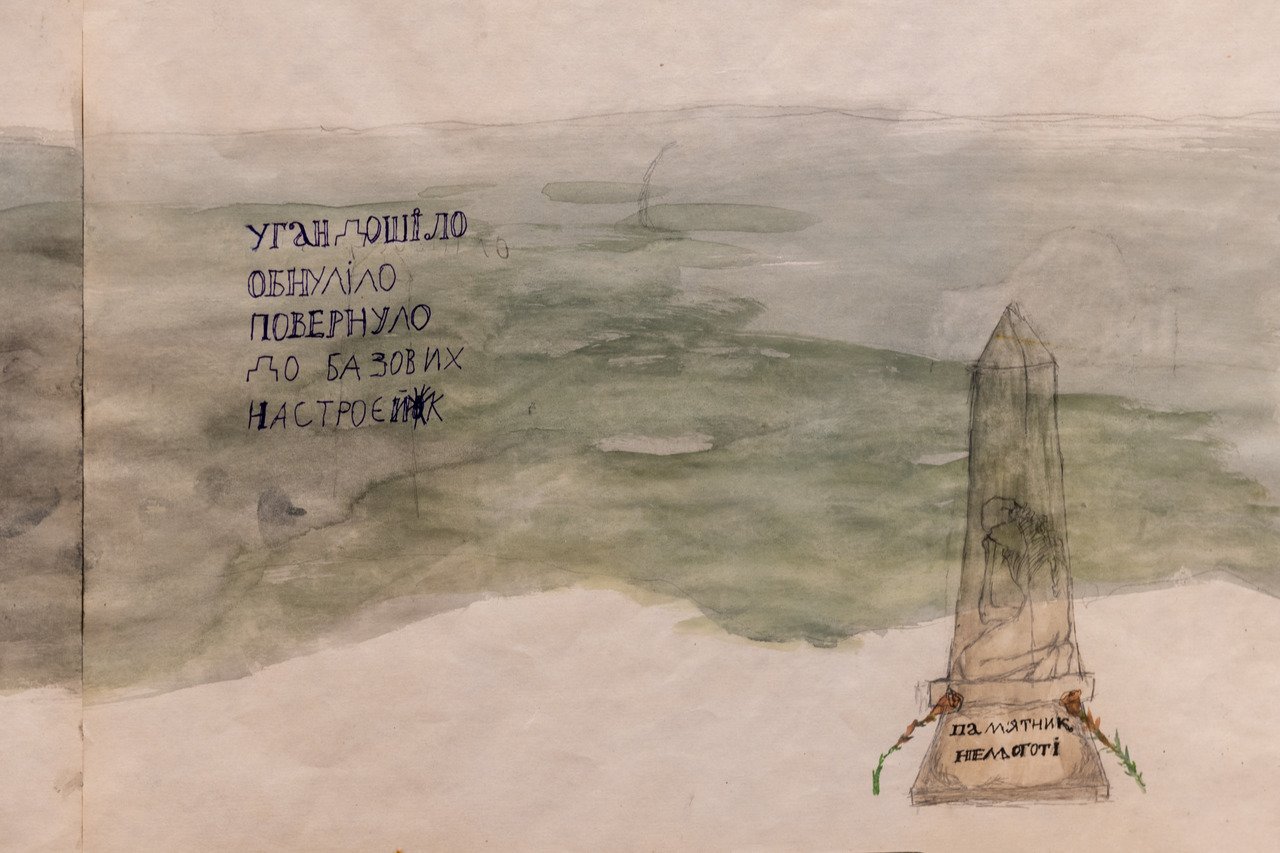

Dasha Chechuskova’s Mournful Surf narrates how the collective traumas prompted by war intersect with her personal experience of loss. Born in Odesa, a resort city beside the Black Sea, Chechuskova fled her hometown in 2022 to escape bombings and seek refuge in Lviv. Her first return to Odesa since that time was in 2023, compelled by her grandmother’s funeral, a moment tragically coinciding with the Russian destruction of the Nova Kakhovka dam on June 6, 2023. Situated at the southern mouth of the Dnipro River, where it flows into the Black Sea, the dam’s collapse sparked a catastrophe, flooding Kherson and neighboring towns. Everything – rubble, vehicles, mud – was swept into the Black Sea, affecting shores from Odesa to neighboring coastal regions. Chechuskova’s work – a concertina-style folded painting – portrays the panorama of the Black Sea during that time, with scenes of roofs and other remnants floating in the water.

An especially poignant aspect of Chechushova’s work is how she uses language and integrates it into the depicted landscape. Before the full-scale invasion, Chechushkova primarily spoke Russian in her daily life, a common practice in the Odesa region; however after February 24, she gradually transitioned to speaking Ukrainian. It is important to note, especially for non-Ukrainian readers, that Ukrainian and Russian are distinct languages, each with unique sounds that can be challenging to master for those transitioning between them. Despite most Ukrainians understanding and speaking Russian due to Ukraine’s history as a Soviet colony and the pervasive Russian influence after Ukraine gained independence in 1991, it does not work the other way around. Russians typically do not understand Ukrainian. Consequently, many Russian-speaking Ukrainians, in response to the full-scale invasion, have switched to using the Ukrainian language as a form of resistance and to distinguish their identity from the colonizer.

In her work, Chechushkova illustrates how switching from one language to another, from one way of living to another, necessitates leaving behind what was once familiar. Chechushkova writes on the panoramic work sentences, short poems, or word combinations that phonetically resemble Russian but are transliterated using Ukrainian letters. These then transform, adapt, and evolve into fully Ukrainian words. To illustrate the transition and the interlingual sonic resemblance in Chechushkova’s language, I attempted to translate a small excerpt. Any orthographic mistakes are intentional.

Starting in Russian:

— Forgive forgive

Forgive forgive

The words evolve:

For frog for

Fare faregive

far

and end in Ukrainian:

Farewell.

Chechushkova’s original text:

— Прості прості

прості прості

про просо про

прощ прощті

про прощавай.

The land also holds memory. Cities and places that bear witness to tragedies, another theme of the exhibition, unveil the context of life during Russian occupation. This theme is evident in the works of Kinder Album, an anonymous artist from Lviv, who created some of her works based on recorded testimonies collected by the Memorial Project, an online commemorative platform that compiles stories of civilians and soldiers who have been killed during Russia’s war against Ukraine. Her work Ukrainian forests filled not only with folklore characters but also with material evidence of Russian war crimes immediately brought to my mind the forests of Izyum. In September 2022, after the Armed Forces of Ukraine liberated the Kharkiv region, where the city of Izyum is located, the world witnessed yet another site of atrocity and Russian war crimes: mass graves of Ukrainian civilians in the pine forests.

Following Kinder Album, Daria Molokoiedova’s Glass House is a reflection on her childhood home in Kramatorsk, a city in the Donetsk region, which remains inaccessible for the artist due to its close proximity to the frontline. She created a miniature house made of cracked glass, symbolizing the fragility of the sense of home and safety. The house is filled with black soil that hardens, dries out, and cracks as time passes. Just as the personal memory of home appears to shatter the longer it remains inaccessible, so too does the land seem to fracture and break under enduring cruelty. Olha Kuzyura’s work combines the approach of both Molokoiedova and Kinder Album’s to address the memory of a place, illustrating how personal and collective remembrances can form a sanctuary where the sorrow for what or who was lost, can be channeled. For Unburnable, the artist collaborated with Northern Cultural Capital, an NGO that collected women’s testimonies of the occupation in the Chernihiv region, which was controlled by Russian forces in early 2022 and liberated in April 2022. Kuzyura’s expedition to the Chernihiv region traced the locations mentioned in those testimonies.

The work is composed of blind-printed fragments from various architectural structures in the Chernihiv region that were destroyed by the invaders. These include elements of wrecked bridges, fragments of burnt houses, and more. Initially, Kuzyura worked on her piece alone, uncertain of how the locals would react upon learning about her project. However, the citizens of the Chernihiv region began to contribute their own “fragments of memory” by asking the artist to make paper imprints of the war-torn buildings that held value to them. The collective “memory fragments” culminated in an artwork that calls to mind the religious story of Virgin Mary and the Burning Bush – Mary is surrounded by fire, yet remains untouched by it. The icon holds significant meaning for the Chernihiv region, home to many wooden architectural monuments of Ukrainian cultural heritage, including churches. Traditionally, the Burning Bush was believed to protect these wooden structures from fire. By creating the icon from fragments that have endured the “fire of war,” Kuzyura seeks to invoke protection and prevent such devastation from recurring.

As I wandered around the gallery, groups of young people would enter and leave. They moved through the exhibition, taking pictures: of the artworks, of themselves, and of themselves with the artworks in the background. They visited the gallery bar and grabbed something to drink before leaving. The scene repeated itself several times during my visit – different people, same ritual. It made me reflect on the point of such exhibitions, and contemporary Ukrainian art in general, to search for threads that connect us. To find points of contact where those who suffer from the war can understand and help each other cope with the witnessed atrocities. Yet, while the sense of connection remains the desired outcome of the exhibition, a sense of non-relatedness may also be present.

As a man in this time of war, I often find myself in a state of limbo. Witnessing exhibitions like these intensifies this feeling, as I can’t help but wish there were more artworks and exhibitions that convey the male perspective during war. Russian aggression has placed contemporary Ukrainian male art in a fragile position. Male artists may be unable to create or share their work for many reasons – mobilization, fear, the need to recover from traumatic events, or even death – yet the need to hear their voices remains profoundly urgent. And amidst collective acts of remembering, which are often carried out by women, I feel an unsettling fear that despite this, it is predominantly men who are remembered. I constantly search for works that expose this fear, not only to relate but also for simple affirmation that I am not alone in this feeling.

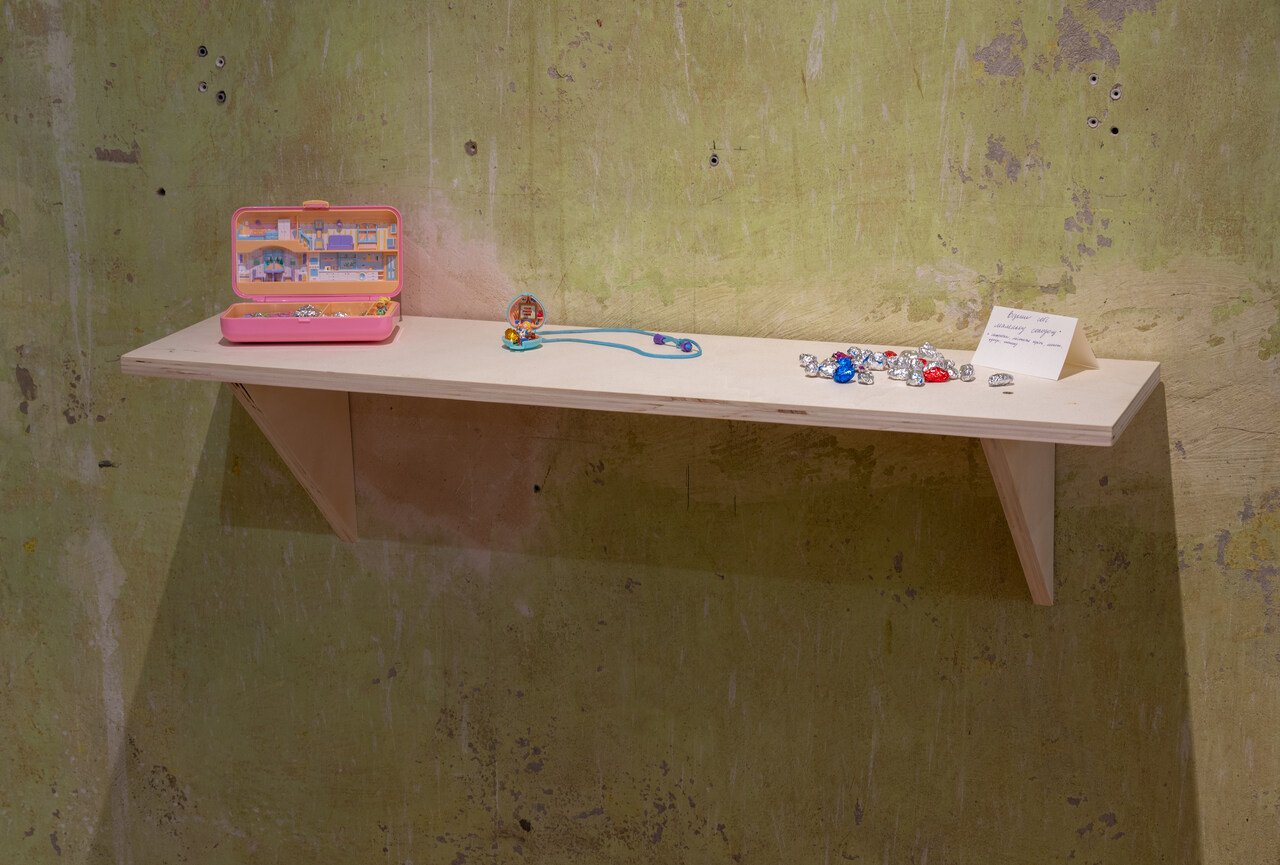

The work of Anna Zvyagintseva, A Tiny Sweet, offered a fitting closure to my observations, as it explores both the past and the hope for a possible future. This artwork originated from a passage in The Choice, a book by Holocaust survivor Edith Eger, where the author recounts her moment of liberation from Auschwitz. On the brink of death from starvation, an American soldier gave her some M&M candies. This simple gesture helped Eger survive and symbolically marked the end of her suffering. Zvyagintseva connects this story to the memories of her grandfather, who, throughout her life, would tell her to always carry something sweet with her, a memory the artist has transformed into her artwork consisting of a little Polly Pocket toy – which is a symbol of the pick-up-and-go nature of war, where Ukrainians escape danger carrying only evacuation go-bags – and chocolate sweets wrapped in colorful foil, which visitors were encouraged to eat.

I take a little candy and taste it. It is a blend of chocolate and nuts, and the hope that maybe this very sweet could bring such long-awaited news of the war’s end. Yet the war persists. Perhaps I should try again on another day, or maybe the candy should have had a bitter taste.

Following its showcase in Kyiv, the exhibition traveled to Dnipro, where it is now on display at the Artsvit Gallery until October 5th, 2024. I sincerely thank the exhibition’s organizers and the Partnership Fund for a Resilient Ukraine for making “The Soil Under My Nails Reminds Me of Dried Blood” and this text possible. I would also like to personally thank Alya Segal and Ivanna Kozachenko for the conversations and insights that have informed my work.

Artist(s):Kinder Album, Dasha Chechushkova, Olga Kuzyura, Daria Molokoiedova, Marharyta Polovinko, Anna Zvyagintseva

Exhibition Title: The Soil Under My Nails Reminds Me of Dried Blood

Venue: The Naked Room

Place (Country/Location): Kyiv, Ukraine

Dates: 05 – 29 June 2024

Curated by: Alya Segal

Produced by: Iryna Polikarchuk, Oleksandra Shovkun (Artsvit Gallery)

Photos by: This exhibition is supported by the Partnership for a Resilient Ukraine, funded by the governments of Canada, Finland, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States of America.

Photos by: Serhii Illin