Weronika Wojda

Semen fell from heaven and Arkadius fell in and out of favour with the fashion gods. He was sensational, internationally successful, and controversial: the new John Galliano or Alexander McQueen. The fashion designer, named Arkadiusz Weremczuk, was born in Parczew, a small village 180 km east of Warsaw, and was active in his eponymous brand from 1999 until 2005 – just one year after Poland joined the European Union in 2004. Arkadius graduated from Central Saint Martins, London, presenting his collection Semen of The Gods as his thesis in 1999. His last show, A/W 2005/2006 Le Cock, was plagued by financial troubles and a lack of investors. After falling into great debt, Arkadiusz Weremczuk retired from the fashion industry, swore off his brand-persona, and banished himself from both Western and Eastern Europe, relocating to Brazil in 2006. Apart from an occasional project, he has rarely been heard from since. Now, the Central Museum of Textiles in Łódź (CMWŁ) presents a retrospective exhibition dedicated to the creator titled Arkadius. Powerful Emotions. Confrontations, curated by Marcin Różyc, on view until July 27, 2025.

Arkadius. Powerful Emotions. Confrontations presents us with the view of multiple runways in a church-like, three-nave setup showcasing Arkadius’ collections, appearing in chronological order, designed by artist Zuza Golińska. The “holy” paraphernalia are paint, hot glue, objects that could be found in a women’s boudoir or a Catholic sacristy, embroidery, and ad hoc pieces of leather, adorning pieces that expose crotches, breasts, and backs. The spatial arrangement of a basilica references the designer’s interest in both Catholicism and Greek mythology. Beyond that, between the lines and threads of the exhibition, one can get a sense of a specific libidinal investment in the act of worship.

The exhibition doesn’t highlight one particular aspect of Arkadius’ oeuvre but instead shows a broad overview of his career. What it does, subconsciously or not, is contextualise his phenomenon within the frame of the sociopolitical changes happening in Poland at the time. The so-called “transformation,” occurring from the 1980s, directly influenced the formation of the middle class, its members being the audience for Arkadius’ works. The particular attachment Polish people have to his persona could be explained through the confrontation with Magda Szcześniak’s “counterfeit theory” of the middle class. She points out this particular strata as suffering from impostor syndrome, as Western capitalism exposed them to lacks in their own collective identity. The desire for cultural indigeneity and recognition in the West, not as Other but as an indistinctive member of capitalistic society, is present in the exhibition. The other affect is one related to melancholia, as we observe the difficulties caused by said desire. The story of Arkadius at CMWŁ is shown through the narrative of the “rise and fall” and seemingly it is not the clothes but rather the designer himself, who takes centre stage.

Arkadius’ silhouette and face appear throughout the show often, and in a very distinctive way. In a photograph displayed in the central nave, the designer is looking up wearing only white pants, covered in a blood-like substance, holding his own head which has been severed at the neck. His visage, adorned with a crown of thorns, is also embroidered on garments. In one of his most circulated photographs, Arkadius is seen closing the S/S 2002 collection titled Virgin Mary Wears The Trousers with a parade of bodies showcasing his designs, standing in a row behind him. He is wearing red leather pants, his chest is bare and his arms are spread wide with his ribs jutting out. There is a crown of thorns on his shaved head and a black rosary-style necklace around his neck. His figure is surrounded by a halo of golden fabric with a mass of pink ribbons and holy images attached to it. The imagery here is obvious and so is the self-igniting cult of the individual.

An article about Arkadius in the January 2002 issue of Polityka was headlined Pierwszy Polak w świecie kreatorów mody (The First Pole in The World of Fashion Creators). In 2021, Polish Vogue published an article by Kamila Wagner with the title Sława, upadek, ucieczka – krótka historia Arkadiusa (Fame, Fall, Escape – The Short Story of Arkadius). That same year a podcast series called Supernova, produced by Audioteka, narrated the increasing frenzy around Arkadius. It highlighted the ambiguity of his career and its reception in Poland, his position in the international fashion industry, as well as his aspirations – which seemed ill-fitting for the reality of his peripheral home country. Despite this, his success was, and perhaps still is, mesmerising to the Polish public. The CMWŁ show name-drops his fans and supporters on multiple occasions; he was adored by Isabella Blow and Suzy Mankes, and Christina Aguilera, Debra Shaw, Karolina Kurkova, Bjork, and Mary J. Blige have all worn his clothing. The written descriptions throughout the exhibition space are full of references and quotes praising the designer, including media outlets such as the International Herald Tribune, Vogue, Elle, The Guardian, and The Face. He made it out during a moment when no one else from Poland, a once capitalism-forsaken country, could.

Arkadius’ rise and fall happened on the cusp of the new millennium. The specific attachment the Polish public had to his persona is symptomatic of what he encapsulated in the context of the systemic transformation, from communism to capitalism. As mentioned before, in the CMWŁ exhibition and in the public discourse, Arkadius is constantly being singled out for being the only Pole present in one of the most notoriously exclusive industries. He was the representative of national identity for the emerging, aspirational middle class. But why was this strata so anxious to become part of the Western fashion world?

The hegemony of capitalism is introduced through language, sets of behaviours and mannerisms, as well as tastes. In times of the transformation, amassing cultural capital, for example through art or fashion, was understood as the key to amassing economic capital. In capitalism, fashion is a form of commodified expression which unifies those of similar socioeconomic standings and differentiates them from the others. Moreover, according to Georg Simmel, it is the affluent who dictate ways of dressing that trickle down to the lower classes.[1]

Clothes become a way of advancing class and social status, with those from the bottom mimicking those at the top. A need that the modern fashion industry was able to satisfy through the knockoff, an ingenuine imitation. Aside from the use-value of a garment or more often an accessory, it’s the brand name – the logo or the monogram – that are being counterfeited. The knockoff is meant to simulate the genuine object and is only valuable if its true identity is not discovered. The existence of the original permits the existence of the fake, but in the free-market economy, or at least in fashion, it’s the fake that further enhances the desire for the original. The concept of the knockoff, as it appears in Magda Szczesniak’s Visibility Norms. Observations on the Visual Culture of the Polish Transformation, becomes a term with sociocultural implications. The book focuses on the period of the transformation – the systemic change from communism and planned economy to liberal democracy – a formative moment for the Polish consumer that started in the 1980s and lasted until the early 2000s. Under these circumstances, the Polish public could enjoy commodities that were staples in Western societies. The first, highly anticipated McDonald’s restaurant opened in Poland in the centre of Warsaw in 1992. The invitation-only event was highlighted by the presence of, amongst others, the poet Agnieszka Osiecka and the Minister of Labour and Social Politics, Jacek Kuroń, who was responsible for cutting the ribbon. The guests dressed up, drank champagne and vanilla shakes and ate burgers and fries. To some, the menu wasn’t a surprise but rather a disappointment. One journalist stated that Poland is geographically and symbolically too close to Moscow to be taken seriously by the American company and lamented the narrow food selection. The concern about the proximity to the USSR demonstrated insecurity about the Polish position in the Western free market.[2]

Systemic transformation has a colonial nature. Western societies were being imitated through the consumption of brands and products, which generated an intricate sentiment of inhibition. Szcześniak attributes a sense of imposter syndrome[3] to this emerging Polish middle class, as its whole existence is based on a norm determined by Western societies which couldn’t be accessed from behind the Iron Curtain, other than through singular stories and objects acquired in illegal or unorthodox ways. This distance stimulated the desire for capitalistic signifiers. Szcześniak directly refers to the middle strata of Polish society as “the knockoff project,” indicating its inferiority in relation to its Western counterparts. The biggest disadvantage of the Polish middle class was its lack of generational capital, wiped by years of German occupation and the communist regime. The transformation had a clear theoretical teleology and a Western standard: bringing “normalcy” to an “abnormal” political and economic system (communism).[4]

Fashion, in this freshly capitalistic society, became the marker of belonging; it was a signifier that could be easily recognized. The representatives of the middle class had to have the skill of demarcating its fellow members through visual codes: the clothes and brands they wore. Fashion and the knowledge of fashion was the demarcator of belonging for the middle class, and as Szcześniak writes after Bourdieu, it’s the aesthetic hierarchy that strengthens the class society structure.[5] The tone of superiority is, perhaps, symptomatic of the insecurity that penetrated the Polish middle class, which found itself to be unfit and lacking in the face of the progressing transformation. For the first time, magazines like Sukces were giving advice on proper etiquette and savoir-vivre for the novice businessmen, for example, the right choice of watch. Later the magazine started mocking sartorial faux-pas and would point towards the signs of a lack of “class,”[6] whipping the inexperienced Polish consumers into shape.

In 2009, more than two decades into the process, another American giant appeared on the streets of Warsaw in an attempt to fill the consumer void. Milena Rachid Chehab posed a question about it in the title of her article in Przekrój: Starbucks – dlaczego przepłacamy za kawę? (Starbucks – Why Are We Overpaying For The Coffee?).[7] The author considers the white paper cup with the green mermaid logo to be the peak of pretentiousness and ironically likens finding a free spot in the newly opened cafe to fulfilling the American dream. Similarly to McDonald’s, it was not the product that attracted the public, but the brand. The paper cup with the logo is the symbol of the Western working class. Under capitalism, it belongs to the people who are proud of their lack of time because they are too busy working towards their successful careers. Rachid Chehab, clearly disillusioned with the teleology behind the transformation, awarely presents the broader context in which the coffee drinking becomes hype, or commodity fetishism, rather than enjoyment of a quality drink. The “knockoff project” theory presented by Szcześniak is derived from the experience of the colonisation of the country’s identity through the introduction of Western brands and consumer goods like McDonald’s and Starbucks. In the case of Arkadius, and the reason why he remains so popular might be because he destabilised the “knockoff” status of the middle class, or at least exposed its complexity.

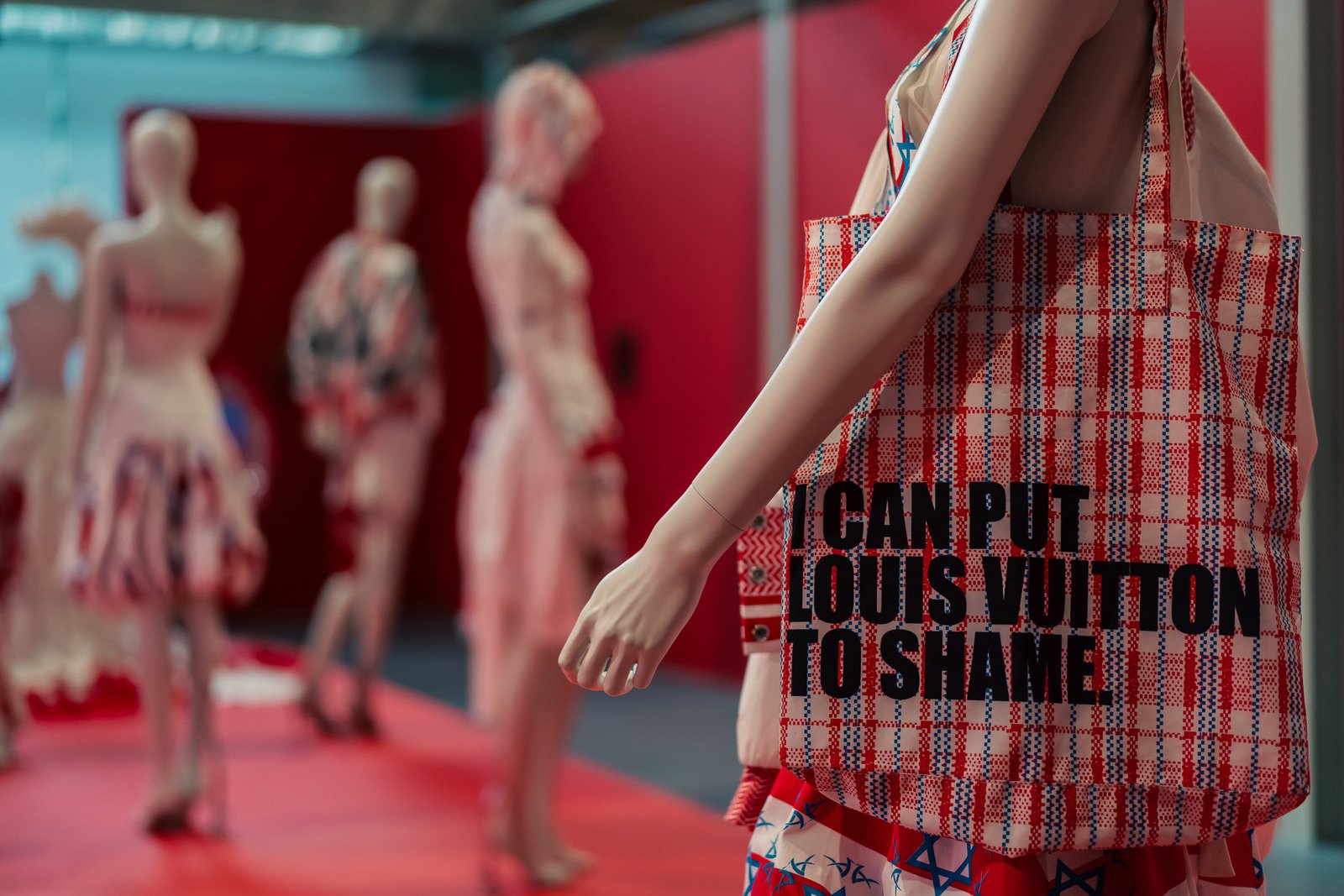

Arkadius’ collections disclose an awareness of the position he found himself in, as a representative of Poland with a certain desire to take part in the global discourse. The S/S 2004 collection United States of Mind is a take on global, read: Western, political concerns. The garments combine motifs of the Palestinian Keffiyeh, the Star of David, and the American dollar into ludicrous patterns. Through this collection, Arkadiusz was expressing a hope for peace but also engaging in the critical discourse around the involvement of the United States in the conflict between Israel and Palestine. Regardless of whether his take was naive, controversial, or even politically incorrect, it is seemingly, first and foremost, cosmopolitan.

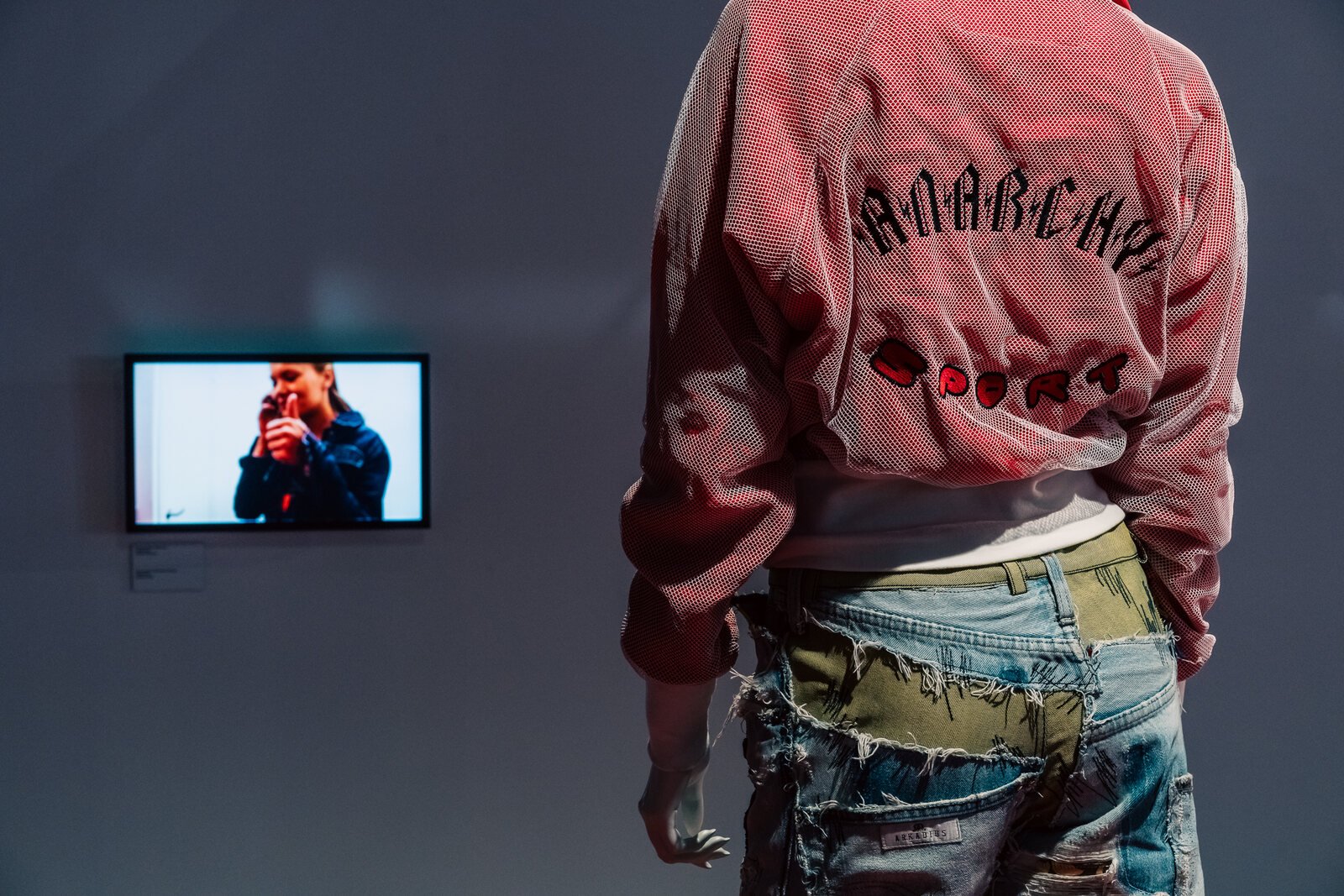

Simultaneously, Arkadius is deeply tied to his Polishness, even though he hasn’t lived in his home country since 1992. His collections such as S/S 2001 Paulina referenced Polish folklore and the life Arkadius had in the countryside with his grandmother. Hay came out from under traditional costumes which were mixed with red and white cutout patterns. The Catholic symbolism reproduced by the likes of Madonna in Western pop culture was presented in his S/S 2002 Virgin Mary Wears The Trousers collection. The garments were revealing and sexualizing and the shows were iconoclastic, creating controversy and generating attention. The priest’s stole or traditional crochet patterns were transformed into skimpy bras. Closing the show, Arkadius positioned himself as Jesus. While the designs were adored in London, it is likely that they would have been shunned by the general public in Poland, as to this day it remains a country with over 70% of the population declaring themselves as catholics.[8] In the aftermath of the Virgin Mary Wears The Trousers collection, Arkadius faced backlash from the catholic right-wing press, and his family in Parczew was questioned about their son’s “anti-catholic antics.”[9] Arkadius notes a lack of understanding for his artistic interests in Poland and the sense of freedom he felt when living in London. Rather than creating controversy, he was interested in exploring the notions of sexuality, gender, race, and “the rights to pleasure,”[10] which can be seen in collections like S/S 2000 Lucina, O!, with models covered in red paint wearing fake conical baby bumps, brandishing “newborn” baby dolls. In the collection A/W 2001 Prostitution? Arkadius deconstructs the business suit to reveal the body and mixes it with fishnet stockings and red fur coats, intersecting the signifiers of office work and sex work.

Arkadius described the closing of his brand in 2005 as standing on top of a “golden mountain” and the eventual disappointment with the realities of Western success and the lifestyle he wished for. Despite leaving London and his fashion career, the designer stated he had no regrets. Burdened with economic losses and stresses of the fashion industry, Arkadius exchanged his belief in capitalism for a belief in the “good life,”[11] meaning a peaceful existence close to nature on an island in Brazil.

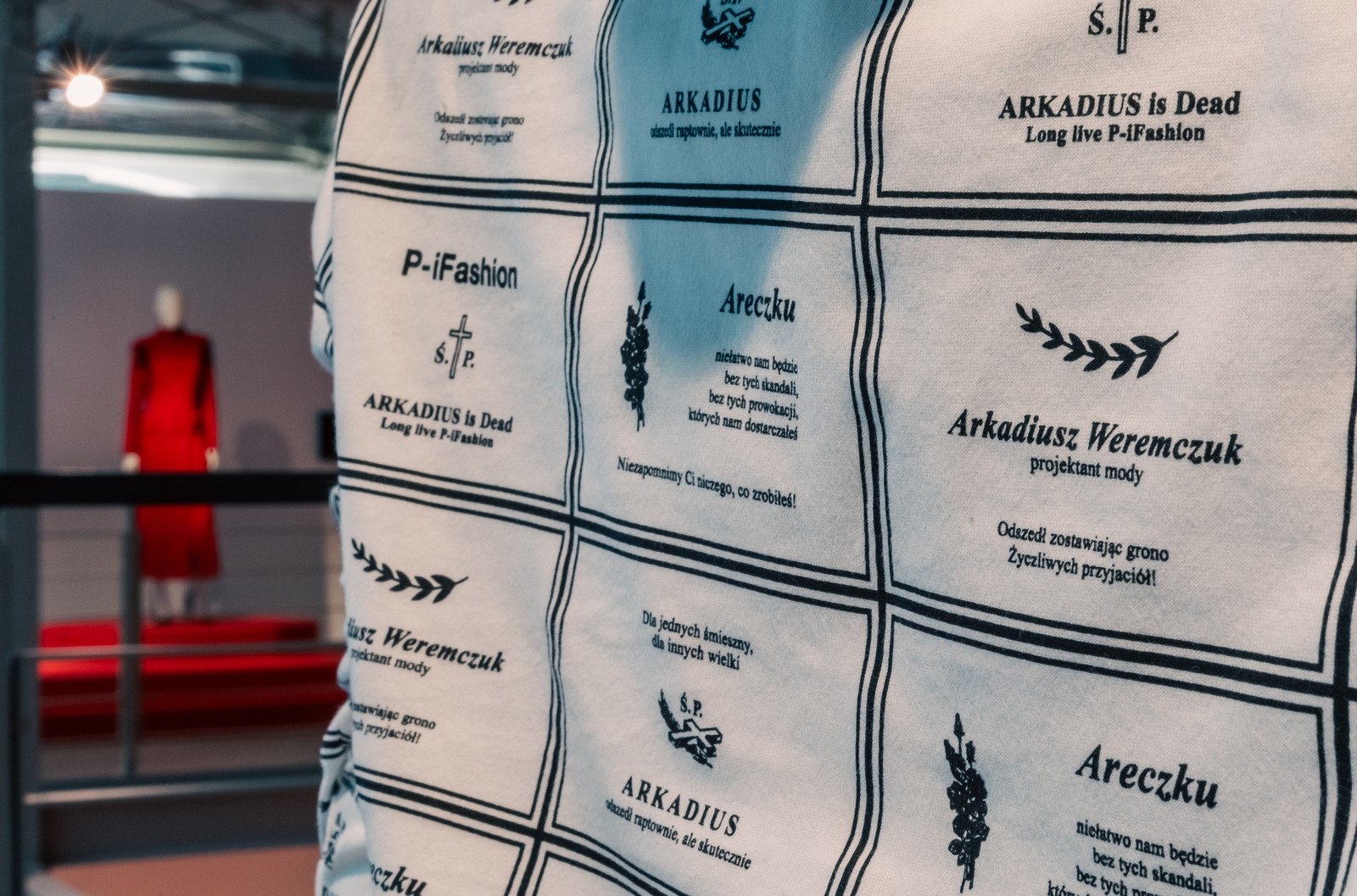

In 2016, he paused his self-banishment only to announce himself as gone. He came out with a limited collection titled Arkadius Is Dead under the Polish label P-iFashion (Politically Incorrect Fashion), consisting mainly of prints of his own obituaries. It’s presented in the finale of the CMWŁ exhibition and could be considered his last work. His name, multiplied in variations and diminutives like “Areczku,” covers the garments alongside expressions of sorrow by fans, family, and friends. With this collection he stages his own death and invites the audience to mourn it, presenting himself as the lost object. With the retelling of his story and the repetition of his disappearance, he is being lost over and over again. The temple at CMWŁ is, in fact, a shrine.

According to Freud’s Mourning and Melancholia. Both of these effects can be experienced after a death or the loss of a loved object, in a broad sense. The difference between them is that “when the work of mourning is completed the ego becomes free and uninhibited again. […] The melancholic displays something else besides which is lacking in mourning – an extraordinary diminution in his self-regard, an impoverishment of his ego on a grand scale. In mourning it is the world which has become poor and empty; in melancholia it is the ego itself.”[12] In the condition of melancholia one identifies herself with that which is the lost object of love. The sentiment is directed inwards and is meant to be prolonged.

The responses to the process of the transformation, as reported by Szcześniak, were often internalised as impostor syndrome, which is characterised by the questioning of one’s own authenticity and the realisation of a lack. The Freudian explanation of melancholy is based on the transference of this lack onto oneself. Arkadius’ prolonged absence from the public sphere, his perception as the “fallen” designer, and the unavailability of his works (before the exhibition they were kept in the basement of a house in Scotland) has contributed to his status as the lost object. The CMWŁ exhibition pushes Arkadius into the spotlight again, casting a shadow on his designs. The viewers are not meant to be merely mourners of his legacy who will heal but forget him. Rather, they are the melancholics who are meant to see the story of his success and demise as the mirror to their own.

[1]Georg Simmel, “Fashion,” American Journal of Sociology 62, no. 6 (May 1957): 541-558, accessed March 7, 2018, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2773129.

[2] Magda Szcześniak, Normy widzialności: Tożsamość w czasach transformacji (Warszawa: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, Instytut Kultury Polskiej UW, 2016), 53 – 58.

[3] Ibidem, 83.

[4] Ibidem, 19 – 21.

[5] Ibidem, 43.

[6] Ibidem, 138 – 139.

[7]Milena Rachid Chechab, Starbucks: Dlaczego przepłacamy za kawę? Przekrój, June, 20, 2008 https://wiadomosci.dziennik.pl/wydarzenia/artykuly/91099,starbucks-dlaczego-przeplacamy-za-kawe.html.

[8]Rzeczpospolita.pl, Ilu katolików chodzi do kościoła? Więcej niż przed rokiem, December 19, 2023, https://www.rp.pl/kosciol/art39592331-ilu-katolikow-chodzi-do-kosciola-wiecej-niz-przed-rokiem#:~:text=Wed%C5%82ug%20danych%20z%20przeprowadzonego%20w,zadeklarowa%C5%82o%20si%C4%99%2033%20mln%20os%C3%B3b.n-mniej-sa-oficjalne-dane/f2lnf23

[9] Arkadius, interview by Karolina Sulej, “Miłość i Anarchia,” Replika, no. 105 (September-October 2023): 11.

[10] Ibidem, 10.

[11] Ibidem, 12.

[12] Sigmund Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, trans. James Strachey, vol. 14 (London: Hogarth Press, 1957), 245 – 246.

Artist(s): Arkadius

Exhibition Title: Arkadius. Powerful Emotions. Confrontations

Venue: Central Museum of Textiles in Łódź

Place (Country/Location): Łódź, Poland

Dates: 9.06.2024-27.07.2025

Curated by: Marcin Różyc

Photos by: HaWa